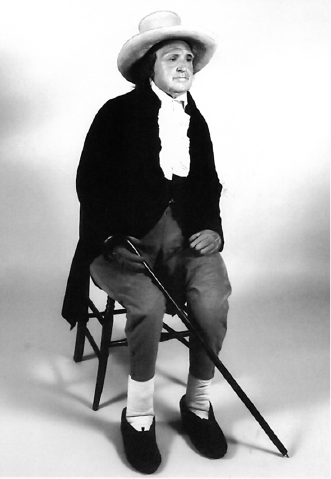

Jeremy Bentham’s Auto-Icon, produced 1832–1833. Modern presentation without cabinet.

Jeremy Bentham’s Auto-Icon, produced 1832–1833. Modern presentation without cabinet.

Toward the end of his life, Jeremy Bentham abandoned his obsessive fight for the Panopticon. A new experiment took its place, a second attempt to evaluate utilitarian theories, which he outlined in his final essay, “Auto-Icon, or Farther Uses of the Dead to the Living.” By 1769, at the age of twenty-two, Bentham had already decided to bequeath his body to science, to compensate—as a dead man—for the opportunities to do good he may have missed in life.1 The fulfillment of this childish prophesy stared the aged Bentham in the face daily. The chance to succeed Montesquieu had been refused him. Bentham hadn’t written the constitution for any states. Although his total writings comprised nothing less than the foundation for a utilitarian world order—an “all-comprehensive Code (or say, in one word, of my Pannomion)”2—and although he created a “science of legislation” to complement the “science of morals,” he never enjoyed a decisive breakthrough. For years, Bentham had contacted reform-friendly governments around the world, had offered his services in North and South America, Russia, and Europe. And when he finally was hired to author a liberal Portuguese constitution in 1821, he spread himself so thin that he was ultimately unable to present a final product. To truly become “legislator of the world,” an honorary title bestowed upon Bentham by his students and disciples, would remain little more than a dream of his.3

England forever maintained a reserved stance toward his ideas. The attempts at prison reform soon lost momentum; the establishment of the model prison at Pentonville in 1842 marked the beginning of the grim chapter of brutal Victorian corrections. Not even the shipment of prisoners to Australia would end until 1868. Suffrage laws continued to block most of the population from voting. Moreover, society as a whole was further from an awakening than ever before. Napoleon, the inventor and founder of a modern European civil code, died a warmonger on Saint Helena in 1821, vanquished by the English, whose successes abroad allowed them to defend the old order at home. After a sixty-year reign, Bentham’s archenemy George III was succeeded by George IV (1820), who was followed by William IV (1830) and then Victoria (1837). Restoration swept through all of Europe. Censorship truncated human rights. The aristocracy asserted power and influence, side by side with the burgeoning bourgeoisie. The economy and the state remained closely intertwined, but capitalism had taken on colossal dimensions. A new lower class emerged in the face of industrial magnates’ astronomical fortunes. Farmers had given way to factory workers, or “paupers,” earning starvation wages. The ideal of economic liberalism proposed by Adam Smith and espoused by Bentham and his students had remained little more than a dream. The time was ripe to do good, and the philosopher hoped for a final attempt at it in death: “Having from my earliest youth devoted my mental faculties to the service of mankind what remains for me is to devote my body to that same purpose.”4

Bentham pondered the topic without regard to dogma, traditions, customs, or established law. He avoided any false pity by applying his theses to himself. He utterly ignored the question of the soul, which historically had been closely tied to metaphysics. He soberly narrowed his focus on the human body and, in a manner unprecedented in philosophy, viewed it as “material.”5 For one, traditional burial regulations appeared profoundly wrong from a utilitarian perspective. The handling of corpses was required by law for hygienic and religious reasons, and by force of habit. This made profiteers of the “undertakers, solicitors, [and] priests.”6 Furthermore, it blocked the economically sensible utilization of the body. To circumvent the prescribed institutional path—that is, to secure the future corpse for “useful” purposes—Bentham declared his body an inheritance. He bequeathed it to his friend Southwood Smith, a surgeon, and stipulated that Smith perform a ceremonial autopsy. Bentham’s body was (initially) slated to serve medical research.

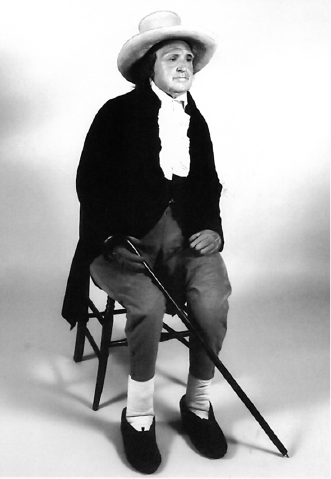

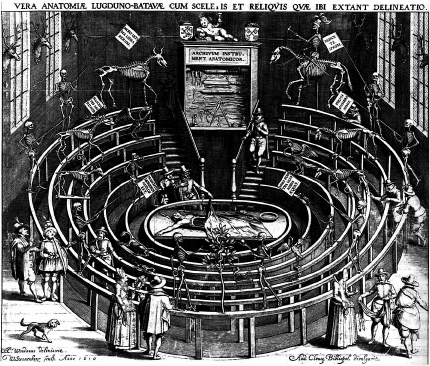

William Hogarth, The Reward of Cruelty, 1751. The height of human barbarism: vivisection of a murderer in an anatomical theater.

Bentham’s act was an affront against his own time. The body—vessel of the soul, a piece of Creation in the likeness of the Creator—was a holy entity. Its destruction was an act of blasphemy by proxy. The law included a single exception, also the result of occidental conventions of thought and action based on the adaptation of Christian cults of image. This exception applied to the bodies of murderers. Following the Murder Act of 1752, their bodies were explicitly earmarked for anatomical study, because vivisection promised mutilation of the face—a sentence greater than death. (Even anatomists themselves insisted on Christian burials, their bodies untouched.)7

In 1824, Southwood Smith lodged the first objection to the established regulations. His pamphlet “Use of the Dead to the Living,” a direct precursor to Bentham’s own contemplations, demonstrated concisely that without foundational anatomical research, the medical field would remain unable to meet contemporary scientific standards:

Disease, which it is the object of these arts to prevent and to cure, is denoted by disordered function: disordered function cannot be understood without a knowledge of healthy function; healthy function cannot be understood without a knowledge of structure; structure cannot be understood unless it is examined.8

By the late eighteenth century, doctors in London had only just won the battle with barbers, whose guild had traditionally been responsible for the dissection of living and dead. In 1783, Doctor John Hunter opened an institute of anatomy with attached museum in Leicester Square. The Company of Surgeons, renamed the Royal College of Surgeons in 1802, campaigned vehemently for doctors to hold the medical monopoly. Uniform hygienic standards were to replace the charlatan practices of cupping and bloodletting visited upon the lower classes by barber surgeons at the fair. At the same time, widespread misconceptions had to be dispelled, such as the practice of “mesmerism,” the use of magnets to alter the nerves, which was well received throughout Europe. This shift could only occur through serious research and practical experience. A societal dimension was thus always inherent to such full-throated declarations of professional ethics as Southwood Smith’s pamphlet. In addition to providing medical care to society’s poorest, the required conversion of poor houses and general hospitals into research facilities also enabled medical training on living bodies: “If the dead bodies of the poor are not appropriated to this use, their living bodies will and must be.” Smith thus invoked the cornerstone of Bentham’s belief system: exemplary social reform built on a utilitarian foundation.

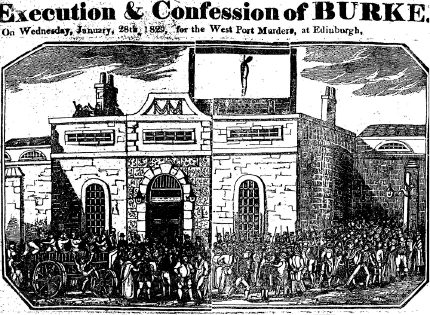

In 1828, a criminal case revealed the heart of the medical dilemma. Two Irishmen, William Burke and William Hare, had for months supplied the Edinburgh surgery with cadavers, which were in short supply; they were delivering, however, not the bodies of murderers but of murder victims. The duo initially exhumed graves (earning them the moniker “resurrectionists”), then moved on to getting petty thieves drunk and suffocating them with pillows. By the end, Burke and Hare were systematically combing the city for fair game, killing runaways and lunatics. Countless cadavers later, the police caught up with them. Burke’s execution in January 1829 drew a crowd of thirty thousand eager spectators. At the public dissection of his body shortly thereafter, the angry mob is reported to have tried to destroy the Edinburgh medical facility; its director, Dr. Robert Knox, was recognized as the actual instigator in the incidents.9

Handbill advertising the execution of the “body snatcher” William Burke. Edinburgh, January 1829.

New ordinances to prevent grave robbery now allowed for triple coffins, patented iron tubs (with springs to prevent the lid from being opened), and multiple rows of nails.10 Copycat criminals and the material costs carried by families further heightened the hysteria surrounding the “body snatchers” (Robert Louis Stevenson), such that they may have helped facilitate Bentham’s dying wishes. Just days after the philosopher’s death, Parliament passed a bill, promoted by those in Bentham’s circle, to reform the Murder Act. Southwood Smith therefore required special permission to perform the vivisection. The procedure provided the opportunity to illustrate a utilitarian paradox Bentham would often vary: under certain circumstances, a small wrong could prevent greater wrongs and thus contribute to human happiness. The mutilation of the philosopher’s cadaver, while officially a “wrong,” served as an example for future cadaver donations; this then made it possible to cover long-term surgical needs, prevent further grave robbery, and most importantly, stimulate research and discovery.

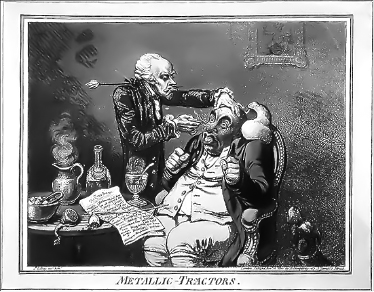

Bentham died in London on June 6, 1832, at the age of eighty-four. On June 8, Southwood Smith invited the public to the Webb Street School of Anatomy.11 A lecture planned for June 11 at the same location would elucidate the significance of this groundbreaking symbolic deed: death, lecture, and vivisection were the first three acts of the dramatic execution of Bentham’s will. Bentham, who had wished to inhabit the eye of the Panopticon as guardian of the inspection principle, now assumed his place in the center of the anatomical theater. The auditorium transformed into an ethics institute. An eyewitness described the event:

None who were present can ever forget that impressive scene. The room (the lecture-room of the Webb Street School of Anatomy) is small and circular, with no window but a central skylight, and capable of containing about three hundred persons. It was filled, with the exception of a class of medical students and some eminent members of that profession, by friends, disciples, and admirers of the deceased philosopher, comprising many men celebrated for literary talent, scientific research, and political activity.12

As master of ceremonies for his own vivisection, Bentham had carefully considered the mix of spectators. Medical lectures were regularly announced and discussed in popular newspapers.13 The illustrious circle of family and friends in attendance piqued further interest, and as eye witnesses they were also expected to ratify the “usefulness” of the scheduled act. Without a doubt, this was a community gathered to profess their utilitarian faith. Southwood Smith paid effusive tribute to Bentham’s character. He enumerated his accomplishments as a political thinker. Then he quoted from the foundational text of his political worldview—the Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation—selecting the key introductory lines from the “Principle of Utility.” Under these circumstances, the words must have taken on the quality of prayer: “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do.”

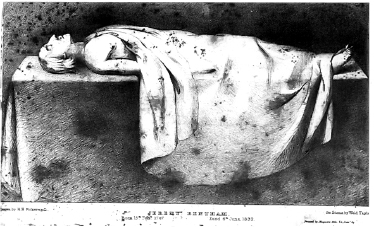

The corpse was on the table in the middle of the room, directly under the light, clothed in a night-dress, with only the head and hands exposed. There was no rigidity in the features, but an expression of placid dignity and benevolence.

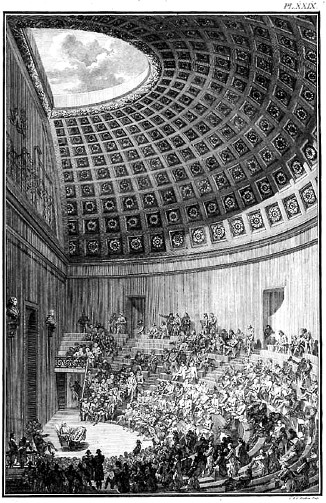

Auditorium at the École de Médicine, Paris. Designed by Jacques Gondoin, 1769–1775. Contemporary copper engraving from Gondoin’s publication, Description des Écoles de Chirurgie (Paris, 1780).

The room itself underscored the holiness of the ceremony. The monumental form of the anatomical theater reflected doctors’ status and heralded their search for the seed of creation, for God’s work and his likeness. Jacques Gondoin’s lecture hall at the École de Chirurgie in Paris (1769–1775) was the first building formulated in this fashion, the hall interpreted as a halved pantheon crowned with a cupula opening to the skies.14 Temples of reason such as this immersed the doctors’ work in a sacred aura. Under the cupula of the Webb Street School of Anatomy—a smaller successor of the Parisian model—and the heavens above, lay the inventor of the Panopticon, related in its own way to the Pantheon and anatomical theaters. Myriad motifs permeated the space. The tension grew as in a gothic novel. When Southwood Smith finally started the procedure, a thunderstorm broke out. The ceremony

was at times rendered almost vital by the reflection of the lightning playing over them; for a storm arose just as the lecturer commenced, and the profound silence in which he was listened to was broken and only broken by loud peals of thunder, which continued to roll at intervals throughout the delivery of his most appropriate and often affecting address.

The deceased Jeremy Bentham on the dissecting table. Frontispiece of Southwood Smith’s publication, A Lecture Delivered Over the Remains of Jeremy Bentham, Esq. (London, 1832).

One can assume that the report intentionally lends the scene its mood, especially considering weather patterns in London, where summer thunderstorms are in no way uncommon and would not otherwise warrant mention. However, the fact that Southwood Smith is said to have spoken “with a clear unfaltering voice, but with a face as white as that of the dead philosopher before him” as the entire building “shook”15 shows that something else was at play: natural phenomena that occur on command are religious spectacles.

Matthew 27: 50–53 depicts the end of the Savior: “Jesus, when he had cried again with a loud voice, yielded up the ghost. / And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent; / And the graves were opened; and many bodies of the saints which slept arose, / And came out of the graves after his resurrection, and went into the holy city, and appeared unto many.”16 In a foreshadowing of Judgment Day, God greets the crucifixion of his son with a show of omnipotence; He buffets the completed sacrifice, imbuing the key moment of Christian doctrine with metaphysical heft. From this point, the revelation is fulfilled: after death shall come resurrection. First, though, come discovery and knowledge. Matthew leaves no doubt as to the effect of God’s sign on the people: “Now when the centurion, and they that were with him, watching Jesus, saw the earthquake, and those things that were done, they feared greatly, saying, Truly this was the Son of God.” The truth was made manifest.

Bentham’s vivisection (with media coverage) unfurls as an analogue to the biblical scene, albeit with inverse intentions, skewed motives, and a different reason for the heavens’ furious interjection: God revolts against His exposure through the human spirit, which has devoted itself—against His will—to knowledge (and therefore temptation) since the days in paradise. By means of Bentham’s body (the Eucharist!), Smith celebrates metaphysics’ final conquest. Materialism and reason triumph and religious dogma founders, proven useless and outdated. In the modern age, it is none other than the doctor who rips the dead from their graves. A simultaneous act of enlightenment and rebellion, for which the philosopher fought for years, and in which his aversion to religion and church had reached immeasurable heights:

Religion is an engine, invented by corruptionists, at the command of tyrants, for the manufactory of dupes.17

Bentham-Antichrist: the revelation fulfilled the moment the surgeon’s scalpel penetrated his flesh. “By this act he carries by his own personal example, the great practicle principle, for the development and enforcement of which he has raised to himself an immortal name.”18 A reporter at the Monthly Repository considered it “a worthy close of the personal career of the great philanthropist and philosopher,” which served as the apotheosis for true heroes:

Never did corpse of hero on the battlefield, with his martial cloak around him, or funeral obsequies chanted by stoled and mitred priests in Gothic aisles, excite such emotions as the stern simplicity of that hour in which the principle of utility triumphed over the imagination and the heart.

As witnessed by students, descendants, and those eager to learn, Bentham became one with his teachings. In place of those for whom he wanted to do good, he entered the infinite kingdom of scientific reason. From that point forward, he was no longer simply the founder of utilitarianism but the very proof of its validity.

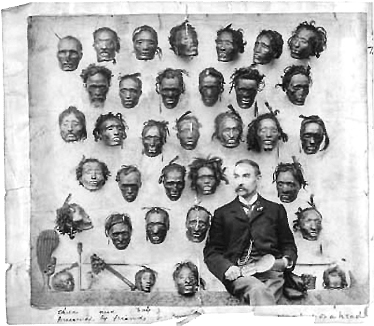

After the execution of the first three acts of Bentham’s dying wishes came the next step. Southwood Smith assembled the dissected parts of Bentham’s body, stiffened the skeleton, dressed it, and arranged it as a living portrait, a so-called Auto-Icon. Straw and cloth were fashioned to provide corporeal volume around the bones and the heart was placed in a glass jar, but Bentham had devised a special procedure for his head after its removal from his torso. It was to be prepared according to the drying methods employed by the Māori of New Zealand to create mokomokai, or preserved heads. The cultural practice, first described in Captain James Cook’s account of exploring the South Seas, had become known to the wider public in London through the 1820 visit of Hongi Hika, a Christianized Māori intermediary enlisted to promote cultural exchange between indigenous peoples and colonists, who became a society favorite. On the return voyage to New Zealand, Hongi Hika traded gifts from King George for new types of firearms, called his tribe into battle, and unleashed an apocalyptic bloodbath on their rivals. Following each victory, the enemy heads were dried en masse and traded for more weapons. Scores of mokomokai thus made their way to England, where they were showcased, acquired by museums, and gathered by collectors, even following the 1831 trade prohibition.19

Bentham was by no means fazed by either the massacre England had indirectly prompted or the ritualized cruelty. He appraised the trophies—dismissively dubbed “baked heads”—as technical innovations and recognized their potential for his own plans. He enthusiastically praised the “savage ingenuity.” An 1824 draft of his will was the first to contain the score of his wishes: first, to see the corpse as an inheritance (for “my dear friend Dr. Armstrong” at the time, as he had not yet met Southwood Smith); second, to make a scientific-political example of the vivisection; and third, to put forward the Auto-Icon as a lasting emblem.20 According to legend, Bentham carried around the glass eyes intended for the Auto-Icon in his pocket in his final years. (Supposed) attempts at dehydrating body parts in his home oven are said to have yielded satisfactory results. Bentham believed the mokomokai process would discolor facial traits and produce a parchment- or mummy-like appearance (which could be corrected with paint), while maintaining the physiognomy. For a denizen of the eighteenth century, who believed that facial lines were an expression of personality and a reflection of the soul, this was the deciding factor. Bentham defined “a man who is his own image”: to preserve his “identity,” the Auto-Icon had to correspond exactly to the living man, beyond his death.21

The English Colonel H. G. Robley, following dispatch to New Zealand, poses in front of his collection of mokomokai. Photograph, ca. 1900.

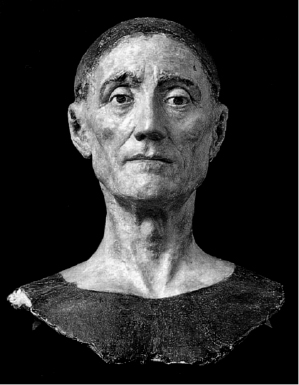

But Southwood Smith botched the job.22 He sprinkled sulfuric acid onto the head, and in doing so docked Bentham’s nose. He used an air pump to aid dehydration, which caused the skin to shrivel. Bentham’s face appeared melted, the physiognomy destroyed. In spring 1833, Smith commissioned a replacement head of wax, for which he likely enlisted the Frenchman Jacques Talrich, a trained doctor who created anatomical instructional materials out of wax and lived in London in the early 1830s.23 In addition to studying painted and drawn portraits, Talrich used two works crafted by the sculptor David d’Angers during Bentham’s 1825 visit to Paris as a template: a marble bust that had been in Bentham’s private collection since 1828, and a medal displaying both the philosopher’s profile in relief and his handwritten signature. The work was part of a prodigious art project comprising over five hundred medals depicting people of note, whom d’Angers viewed as the building blocks of an intellectual pantheon.

David d’Angers (Pierre Jean David), medal depicting Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1829.

David d’Angers (Pierre Jean David), bust of Jeremy Bentham, 1825. Today housed at University College London.

D’Angers reserved a certain scientific pretense for his renderings, based on the teachings of phrenology (the connection between character and skull shape), physiognomy (the connection between character and facial features and proportions), and graphology (the connection between character and handwriting). His medal of Goethe, along with his famous plaster bust of the poet (Paris, Musée d’Orsay) created in 1829 in Weimar, illustrates the approach: since contemporary theories emphasized prominent physical features as the sign of an individual’s intellect and character, d’Angers enhanced those supposed features of genius (high forehead, distinctive nose, flowing tresses) to such a degree that the result eclipsed the individual’s actual appearance. This primacy of artistic stylization on a “scientific” basis also applied to the bust of Bentham—and therefore to the wax head modeled after it for the Auto-Icon. The fact that Talrich’s completed work, trimmed with the philosopher’s real hair, was so well-received by contemporaries—“so perfect, that it seems alive”24—was based less on true similarity in external appearance than on the formal ardor required—and at the time, even desired—in depicting extraordinary intellectual capacity. Realism, or even naturalism, was a concept foreign to this art. Strictly speaking, Bentham’s original idea for the Auto-Icon as “a man who is his own image” was thus a failure.

At the end of the production process, Southwood Smith positioned the Auto-Icon, dressed in its best suit, on a chair, as if it had just returned home after its daily stroll. He placed Bentham’s real, disfigured head on a plate between his slippered feet. Its power as a memorial was tempered by its private bearing. It was not placed on a pedestal, conjuring grandeur and distance. The Auto-Icon lacked the characteristics espoused by exaggerated plaques, as echoed in some accounts of Bentham in his later years:

His apparel hung loosely about him, and consisted chiefly of a grey coat, light breeches, and white woollen stockings, hanging loosely about his legs; whilst his venerable locks, which floated over the collar and down his back, were surmounted by a straw hat of most grotesque and indescribable shape, communicating to his appearance a strong contrast to the quietude and sobriety of his general aspect. He wended round the walks of his garden at a pace somewhat faster than a walk, but not so quick as a trot.25

Bentham managed, despite his approaching death, to remain a part of the society he had often hosted at dinners. The mahogany cabinet housing the Auto-Icon, built with glass doors according to Bentham’s design, thus served a practical purpose: it made “Bentham” mobile. In his will, he encouraged friends and students to meet regularly “at a club in commemoration of my birth and death.” In fact, he wished to join in these gatherings:

My desire is, that in that case order may be taken by my executor, for such my skeleton seated in an appropriate chair, to be placed, on the occasion of any such meeting, at one end of the table, after the manner in which at a public meeting a chairman is commonly seated.26

Jeremy Bentham’s Auto-Icon. Detail of the wax head crafted by Jacques Talrich, 1832.

The Auto-Icon allowed the utilitarian initiation ritual at the Webb Street School of Anatomy to be reprised ad infinitum: with new visitors (including guests such as Charles Dickens), students, and disciples of the philosophical doctrine, and personally presided over by its founder. Along these very lines, Southwood Smith exhibited “Bentham” in the mahogany cabinet in his practice in London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood, and frequently brought him along to social events, parties, and discussions. This ritual continued, albeit with some interruptions, until “Bentham” arrived at University College London in the mid-nineteenth century, following a stopover in a museum. His ability to travel from his current location in the South Cloisters of the main building of UCL, however, is hindered by limited accessibility. Most recently in 2006, his participation in an international conference on utilitarianism was limited to presiding over the speakers’ dinner, which was also moved to a room on the same floor.27

From the first, English society was unruffled by Bentham’s idea, which he had delivered as an ultimatum. The scandal was quickly defused by a long-standing social mechanism for normalizing the bizarre: Bentham joined the ranks of “eccentrics,” a special type of individualist who had emerged in the eighteenth century from the leveled society of aristocracy and elevated bourgeoisie. Among Bentham’s contemporaries were a considerable number of hypernervous characters whose purpose in life was to be different.28 John Mytton, for instance, outdid the sartorial enthusiast “Beau” Brummell through his accumulation of three thousand shirts, one thousand hats, seven hundred pairs of shoes, and one hundred fifty pairs of jodhpurs. He fed his two thousand dogs steak and champagne and clad his eighty cats in livery. And nearly every time he went out riding, he made an effort to kill himself. John Fuller, on the other hand, a parliamentarian and proponent of natural sciences and the arts, appeared to possess a spiritual kinship to Prince Pückler-Muskau. He constructed a range of bizarre monuments, pavilions, and follies on his estate. And finally, the painter-poet William Blake loved to recite passages from John Milton’s Paradise Lost in his garden, and, along with his wife, slip into the roles of Adam and Eve—naked.

The two-volume compendium English Eccentrics and Eccentricities (1866) enumerates over one hundred personalities and incidents, and describes prominent examples of spendthrifts, philanthropists, religious fanatics, opium-eaters, and “radicals”; alongside Bentham, the list also included the rebellious William Beckford with his tirade against King George III. Many of these personalities made use of their impending death for eccentric positioning. Cryptic epitaphs, peculiar bequests, and unexpected inheritances were part of the standard repertoire. Coffins—self-constructed, lovingly designed—were installed in the home as a wardrobe or wine rack during the individual’s lifetime. Memorial cults existed that far surpassed opulent family tombs. And there are absurd burial specifications. In 1800, for instance, General Labeliere was buried on a hill between London and Brighton, his body lowered vertically into the ground, headfirst. He wanted to be prepared: in case “the world was turned topsy-turvy, it was fit that he should be so buried that he might be right at last.”29 Like Bentham, he needed to do this without church approval.

“A man perfect in his way, and beautifully unfit for walking in the way of any other man.”30 This definition of the eccentric, which could also serve as an edict of tolerance, was penned by the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne with regard to William Blake. Every eccentric had to discover his own personal quirk, as a finely contrived medium for social distinction. This was a very specific type of challenge. Thanks to the Auto-Icon, Bentham had clearly passed this test with flying colors. The adoring cult of the weird, however, stripped his project of its philosophical point. Bentham had not intended to become a curiosity. He had wanted to perpetuate the exemplary morality of vivisection. The visual death for science was to be answered by visual resurrection. He sought to appeal to observers. The Auto-Icon was an invitation to imitate life according to the principle of utility. It was the final puzzle piece in Bentham’s sweeping project of social reform, and as such, it was trained on eternity.

Southwood Smith did not pass the memento on to a museum, but installed it in his own chambers, because Bentham had contended that the moral influence of any Auto-Icon would develop best amid those who survived the deceased. The argument is plausible when considered in the context of curio and natural history collections, the Kunstkammern or “cabinets of curiosities” that had been filled with treasures from church or royal troves from the sixteenth century onward.31 In a cabinet of curiosities—an antecedent to the modern museum laid out according to “Artificialia,” “Naturalia,” or “Exotica”—objects of motley provenance were displayed together, in contrast to later collections’ scientific and systematic arrangement. Morphological criteria were deciding factors, but most important was the nod to the collector as a gentleman of moral integrity and political acumen. Viewed holistically, these collections of nuts, ostrich eggs, turnery, whale bones, automatons, gemstones, and hunting trophies could each serve as a miniaturized model of the universe. Ancestral portrait galleries often attached to the cabinet of curiosities extended this cosmic symbolism directly to the collector himself. There are several analogies between the Auto-Icon and cabinets of curiosities: taxidermied creatures, inanimate objects imitating life (automatons, the portable Auto-Icon), the reference to the collector’s political or moral intentions, the attempt to craft an explanation of the world (through objects, through philosophy), and finally, storage in a special spot—the cabinet.

In addition to princes and other royal collectors, artists (including Rembrandt, who was so interested in medicine) and doctors were also among the first to establish cabinets of curiosities. The close parallels between the cabinet of curiosities and surgery are clearly depicted in a 1610 engraving of the anatomical theater in Leiden. Objects explicitly designated as relics are gathered on the wooden balustrades reserved for spectators: animal skeletons and taxidermied birds, grouped in concentric circles mimicking circular models of the cosmos. Flanked by flag-waving vanitas allegories (“Mors ultima linea rerum”), the visitors follow the action at the center of the hall: the vivisection of a human, the apex of creation. Hunting trophies hang from the walls and an open cabinet at the back displays the tools of surgery, natural sciences (a telescope), and mathematics (a compass)—equipment that also played an elemental role in Bentham’s philosophy. The dichotomy between knowledge and religion established in the Bible is addressed in this Baroque engraving. In the foreground of the picture, two skeletons stand on the balustrade and face an apple tree growing between them, a snake in its branches: a reenactment of the Fall. The formulation of the scientific validity claim that defined Bentham and Smith’s experiment remains far in the distance.32 The spiritual-moral framework and media repertoire of the theatrically staged cadaver, however, is fully developed. All of these aspects feed into the Auto-Icon.

Anatomical theater at the University of Leiden, 1610. Willem van Swanenburgh’s engraving was based on a drawing by Jan Cornelisz van’t Woud (Woudanus).

The taxidermied philosopher is thus less an eccentric curiosity than he is the consistent continuation of occidental notions of the universe. Bentham’s Auto-Icon compromises the very idea of the cabinet of curiosities, as it were. It transcends the dimensions of (pre-)museum collecting politics that had been established at that time and fuses elements of its visual practices in a single object. The automaton, skeleton, taxidermied animal, trophies, exotic finds (Bentham’s nod to the Māori), and so forth: Artificialia, Naturalia, and Exotica are united in the Auto-Icon. And the idea of the ancestral portrait gallery is incorporated in the truest sense of the word. The consolidation into a singular exhibit-of-all comprised the moral meaning inherent in cabinets of curiosities (and museums). The systematizing, cataloging, explanation, and control of the world as a whole—allegorically identical to Bentham’s panoptical-pannomionic-philosophical intentions—achieves figurative closure. In this way, the fusion between the body and teachings accomplished in Bentham’s postmortem dissection is preserved forever. At the same time, it is elevated to a new level of meaning: the creation of the Auto-Icon turned the philosopher into his own world model.

The Auto-Icon, however, is not without further precursors. In Westminster Abbey, court chapel of the British crown, so-called funeral effigies constitute an almost uninterrupted parade of heirs apparent from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, starting with Henry VII.33 The power ascribed to the wax figures—that is, sovereign power in effigie—as well as the context of their use changed over time, leaving many holes in the research to this day. One aspect that goes undisputed, though, is the motivation behind creating the figures. It serves as a direct continuation of the medieval conception of the king’s two bodies—the material and symbolic bodies containing the ruler’s god-given majesty.34

When the symbolic body loses its material counterpart in death, a conceptual void remains. It lasts from the death of a ruler until the coronation of the successor. To maintain a connection for the symbolic body in the interim, wooden (and later wax) dummies were invented to represent the deceased monarch as a living (!) person. The effigy, clothed in regalia and often moveable, headed the provisional government until the figure was transported—usually in triumphant posture atop the coffin—with the king’s mortal remains to the funeral ceremony, whereupon it was installed either at or on the tomb in the church. This archaic ritual, which was practiced in France and Venice in addition to England, was upheld nearly until Bentham’s time. And although the symbolic-political implications shifted in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (leading up to baroque conceptions of memento mori, for instance), the principal aspect remained potent: the expression, in act and effigy, of the king’s inviolable and divinely ordained right to the throne.

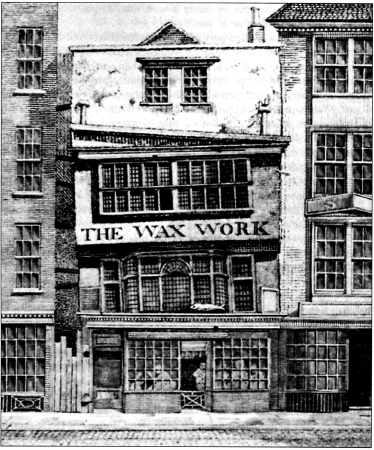

Effigies were also widely used outside the monarchic-sacral symbolic field. In many world cultures, figures of kings and clerics are incinerated and desecrated in a recognized form of representative tyrannicide. The symbolic-political diminishment of effigies in the Baroque era—the transformation from replacement body to memorial object—required their reframing as de-emotionalized museum pieces. The effigy became an object of entertainment. From 1777 in France and 1802 in England, the trained physician Philippe Curtius and his protégée, the Alsatian wax sculptor Anna Maria Grosholtz (later known as Madame Tussaud), displayed likenesses of prominent political and cultural figures in their salons de cire; the statues were exhibited alongside images of anatomical monstrosities, whose designation as a “panopticon” (“curio collection”) supplanted Bentham’s neologism.35 The fact that, despite its functional transformation, the visual form of the effigy did not vanish—but was instead absorbed by memorials of stone and metal—could be attributed to the “lifelike” impression made by wax, which appealed to a large audience.

Wooden funeral effigy of King Henry VII. Westminster Abbey, London, ca. 1509.

In a direct parallel to the development of the panorama, the viewers’ curiosity at Madame Tussaud’s shifted from moralistic examples to causerie and the fun of “as if …” games of conjecture, or optical illusions such as trompe l’œil. At the same time, this success forced the decoupling of dummy, monarchy, and cult. In 1775, the figure of William Pitts the Elder was the first effigy of a politician created as a public image outside the context of a funeral. Westminster Abbey’s very last wax figure, stripped of ritual and introduced as an attraction in 1805, was the likeness of national hero Horatio Nelson, the fallen victor of Trafalgar, the man who vanquished Napoleon. In the embattled waxworks market, the figure contended against Madame Tussaud’s Nelson effigy as well as Nelson’s actual funeral effigy, which was on display in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, where he was buried. Within barely a century, the context surrounding wax figures had shifted permanently. Around 1720, while Margravine Sibylla Augusta did penance in the hermitage on the grounds of Schloss Favorite (Rastatt), encircled by “effigies” of the Holy Family, Philippe Curtius was staging the formal dinners of the king and his entourage in prerevolutionary France: visitors were allowed to touch the figures and their clothing and debate courtly fashions at length.36 The visual form once associated with ceremony and religion had become common entertainment, an entrance-fee industry.

Mrs. Salmon’s “Wax Work,” in a lopsided house on Fleet Street, London. Engraving from 1793.

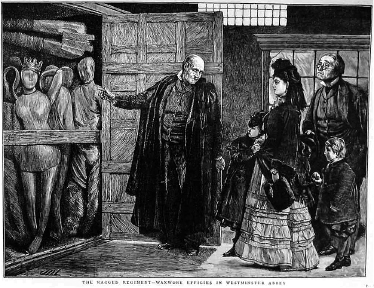

Although it would have been an obvious jab for Bentham the antimonarchist to make, an interpretation of the Auto-Icon as satirizing royal effigies and the divine right of kings comes up short. Regardless of whether these figures’ original symbolic-political contextual range could still be decoded in Bentham’s day, it had begun to blend so thoroughly with contemporary popular culture that the difference between historical church treasures and popular wax figure collections became impossible to discern. Furthermore, in the seventeenth century, loads of effigies in poor condition were cleared into a side wing of Westminster Abbey, where this “ragged regiment” further decayed and served as an attraction for tourists and the boys of Westminster School, where Bentham had started his own schooling in 1755 at age seven. The unheeding treatment of these supposed curiosities in the nave had an increasingly negative effect on the image of other, well-protected royal effigies. “Oh dear! you should not have such rubbish in the Abbey,” an outraged visitor is said to have cried in the late 1800s.37 Bentham responded in similar fashion when he tried to trump such vain frippery as “the lions, the wax-work, or the tomb” with moral edification in the inspection house, or when he connected every form of art with war, alcoholism, compulsive gambling, and an upper class incapable of reform, thereby denying it meaning. Bentham wanted his Auto-Icon to effect a media change in perspective when he promised: “The wax-works in the vaults of Westminster Abbey—Mrs Salmon’s Museum in Fleet Street—yea, even Solomon in all his glory at the puppet-show, would dissolve before it.”38

Visitors at a presentation of discarded effigies from Westminster Abbey, the so-called ragged regiment. Engraving, post-1850.

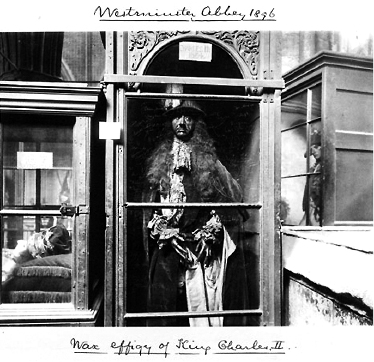

Cabinet of effigies, with the wax figure of King Charles II (d. 1685) at the front. Photograph of the interior of Westminster Abbey, London, 1896.

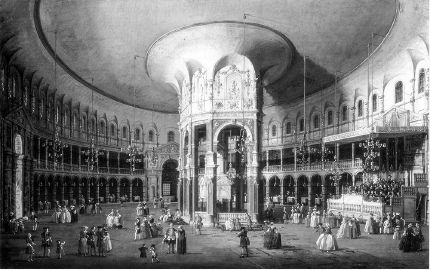

We can thus read Bentham’s Auto-Icon as a critique of certain phenomena of a time that had chosen the road toward mass culture. Wax figures and panoramas, cockfights and balloon flights, funeral processions and circuses, weekends at Ranelagh39—such forms of folk entertainment expressed a popularization that permeated all media and then reflected back onto reality. With the invention of lithography, high-circulation printed matter was made available to the public for the first time. The rise of the newspaper began. Starting in England, caricature as a new form of political criticism swept Europe. This changed propaganda, because despite regimented censorship, the media monopolies held by rulers were gradually softening. Napoleon was consistent in his response, in that he allowed for greater production of images.40 Antonio Canova’s bust in Possagno (1802), for instance, which depicts Napoleon as First Consul, was already dotted with green measuring points for manufacturing copies. With the spread of the empire, portraits of the sovereign were needed en masse, for display in the offices of occupied territories across the continent, where a new generation of civil servants bound by the Code Napoléon dominated the administration. The perennial war between image and counterimage was thus declared: a media spiral that successively reduces the viewer’s sensibility and continuously expands their distance from ur-image and reality.

The Rotunda at Ranelagh Gardens. The pavilion, which paralleled Bentham’s Panopticon in form, enabled visitors to stroll while listening to music. Interior painted by Antonio Canaletto, 1754.

The Auto-Icon defied this development with a clear objective: an object that by definition is neither a portrayal, nor copy, nor media replacement, but nothing other than “a man who is his own image.” “Auto-iconizing” is thus tantamount to the expulsion of the medium from the process of image creation. It is the separation of the image from its communication platform: the installation of the unmirrored, single valid reality as a picture of itself. In this way, Bentham’s implied guiding theme of the “Vera-Icon” is advanced, which he defines as a reduplicated religious cult object based on the ur-image, itself not a human creation: an über-image that renounces media and artistic mediation and ascribes authenticity to its image, which is perceived as “pictorial” and proven by means of thaumaturgy. The Auto-Icon promotes this notion. As a sculpture built of the body parts of the person depicted, the Auto-Icon circumvents the necessary process of reduplication in painting and also does away with the model. It is its own ur-image, the only possible original: authenticity in perfection. By means of this process of media emancipation and purification, it makes restitution for the aura that is lost in mass production. The allegorical significance of the “emblem” regains its old power. In this way—and only this way—can the moral example exercise influence on the observer.

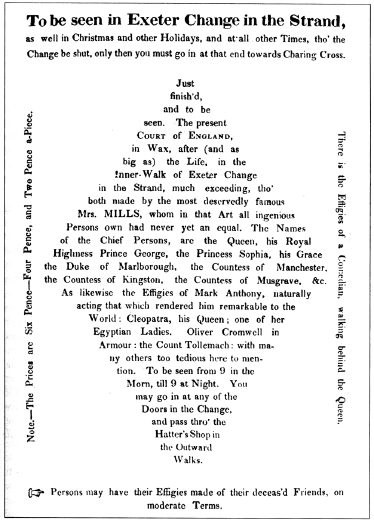

The choice of the New Zealand iconizing process underscores Bentham’s culturally critical intentions. The desired return to the bare essentials was evidently only possible beyond the confines of Western cultural practice—it required the “ingenuity” of the “noble savage.” On the one hand, this conceals Bentham’s antipathy toward colonialism, the one-sided modus operandi of which was provocatively reversed by the use of mokomokai on a member of the colonial power. On the other hand, it also contains a general anticivilization sentiment, echoes of which could be found in the Romantic era, starting with Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The triumph over cultural blindness through edification: the template for societal reform outlined in the “Inspection-House” gains an additional facet through the Auto-Icon. At the same time, the political, religious, and cultural aberrations of civilization appear coequal in Bentham’s estimation. In their own ways, each is commented on and contradicted, and not simply caught but overtaken—and thus overcome. The Auto-Icon further exhausts the provocation of the church introduced by vivisection. By pushing the cult of icon and relic worship too far, Bentham exposes it as a “false” media spectacle. He also repeatedly settled up with the waxworks. While the London-based wax sculptor Mrs. Mill (and later Madame Tussaud) advertised that everyone “may have their Effigies made of their deceas’d Friends, on moderate Terms”41—to live with them at home!—the first figure Madame Tussaud crafted herself, in 1777, was of a famous philosopher, Voltaire. She exhibited him and the figure of Rousseau in many of her salons de cire, including in London. But a “real” philosopher, who vouched for his own teachings as an image of himself, no longer existed—neither in curio cabinet nor private collection.

Handbill from Mrs. Mill’s Wax Work advertising the option to have one’s deceased friends modeled in wax. London, late eighteenth century.

Royal funeral effigies, wax figures, icons, relics, caricatures, portraits, commemorative engravings, early forms of photography, mass entertainment: the Auto-Icon is Bentham’s sweeping media-political blow, his triumph of authenticity as an allegory of utilitarian veracity. Placed in the context of art, it also appears to be an entry in the debate with anatomy, which extended back to the Renaissance and was closely linked to discussions surrounding the formal poles of realism and stylization. This, then, returns us one more time to the field of medicine.

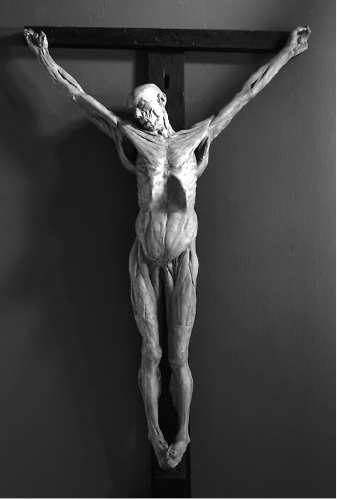

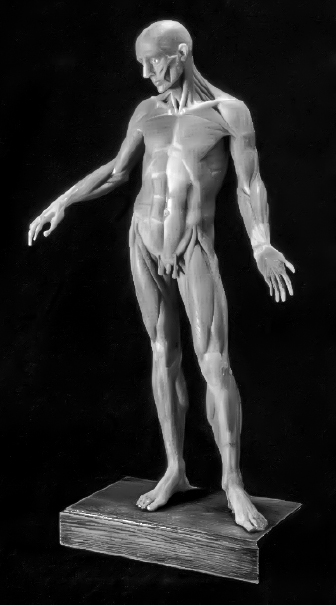

Thomas Banks and Joseph Constantine Carpue, Anatomical Crucifixion, 1801. London, Royal Academy of Arts.

André-Pierre Pinson, Ecorché humain (Skinned human). Anatomical wax model. Paris, ca. 1780.

The study of dead bodies has led to hyperrealistic eruptions time and again, tied to everything from drastic affect to shock. Hans Holbein the Younger’s predella (1521) in Basel, for instance, which depicts the Redeemer’s decaying body, sparked prolonged debates about the boundaries of morality and permissible manners of representation; the picture was long concealed behind a curtain.42 Rembrandt revealed his predilection for medicine in paintings such as The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632, The Hague, Mauritshuis), a combination of group portrait and depiction of the vivisection of a cadaver. In the seven-by-five-meter oil painting The Raft of Medusa (1818, Paris, Louvre), Théodore Géricault attempted to give his work the suggestive power of an “authentic” ur-image and sketched body parts, including the guillotined heads of convicts, in preparation.43 The radical high point in the search for a scientifically founded realism in art was the joint attempt by painters Benjamin West and Richard Cosway, sculptor Thomas Banks, and surgeon Joseph Constantine Carpue. In October 1801, they nailed the body of the freshly executed murderer James Legg to a cross. The Anatomical Crucifixion was meant to help revise the supposedly common incorrect depiction of a body’s deformation upon execution.44 Carpue dissected and skinned the corpse in order to expose its muscles and tendons. Banks undertook a detailed plaster casting. It has been in the possession of the London Royal Academy of Arts since 1802, where it is shown to this day—not as a religious artwork, but as an object of study within the institute’s collections.

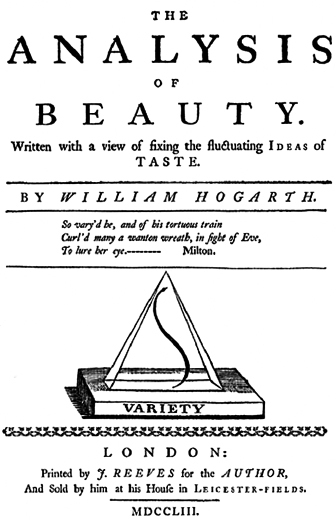

William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty. Frontispiece featuring a drawing of a “serpentine line” in a prism. London, 1753.

This brutal experiment came about suddenly, without regard to either art or medicine. Even the anatomical wax models of the eighteenth century—which were manufactured as visual aids for students and acquired by enlightened monarchs such as Joseph II for the expansion of universities—were often posed in “lifelike” fashion. Sitting men, sans skin, flexed their muscles. Female bodies in erotic poses turned their innermost parts out on hinges. A London-based exhibit of anatomical wax figures in the 1770s showed preserved, real body parts alongside the dissected effigy of a very pregnant woman: fake blood flowed through glass veins, a pump moved the heart and lungs.45 In the trompe l’œil of these artifacts, which circulated in surgeries and art academies alike, the final vestiges of cabinets of curiosities and the vanitas allegory kept cropping up—the pedagogical notion that had shifted its focus from morality to science. The reciprocal relationship between art and medicine here led the Anatomical Crucifixion to a final high point before its predecessors were absorbed by the entertainment industry, where they were to find an afterlife in waxworks, horror novels, and “Body Worlds” exhibits, liberated from all moral and scientific claims.

The disregard for convention, the pragmatic will for knowledge, the realism pushed to the point of intolerability, the historical connection to cabinets of curiosities and anatomical theater, and finally, the educational purpose reveal the kinship between the Anatomical Crucifixion and the Auto-Icon. Beyond its critique of civilization and media, Bentham’s idea thus gains a further dimension: it is part of the academic discourse on the relationship between art and nature, on the rise of technology and science as the dominant culture of Europe, on positivistic “objectification,” and on measuring the world and humankind. The painter William Hogarth had already attempted something similar in 1753, when he “scientifically” deciphered the principles of beauty with his gently curved “line of beauty,” a serpentine ideal form said to underlie all aesthetic graces.46

Yet again, the considerable discrepancy between idea and execution of the Auto-Icon becomes clear. The artwork of David d’Angers—which provided the model for “Bentham’s” wax head—was based (and this may be a hyperbolic formulation) on false physiognomic teachings found dredging the murky waters of metaphysics. Hogarth and the Anatomical Crucifixion were exploring temporal phenomenology with scientific-technical experimental design. Bentham attempted nothing short of the same in his discipline—philosophy—with the felicific calculus. The Panopticon would have been his “academy”: as a place for education and training, and as a laboratory for testing and proving his theories. Consistent and utilitarian. As for what applied to members of the Royal Academy, Bentham also took matters into his own hands by allowing himself to be transformed into the Auto-Icon.

John Stuart Mill, the devoted pupil, painted a comprehensive picture of Bentham’s character. He remained “a boy to the last,” nonjudgmental of others and unencumbered by “self-consciousness, that daemon of the men of genius of our time, from Wordsworth to Byron, from Goethe to Chateaubriand, and to which this age owes so much both of its cheerful and its mournful wisdom.”47 Mill presents us with an image of altruism personified in Bentham, whose mild-mannered good nature epitomizes the integrity of his own teachings. Friedrich Engels, by contrast, reached different conclusions in his 1844 comparison of Bentham’s work to Max Stirner’s The Ego and His Own: “The noble Stirner … takes for his principle Bentham’s egoism, except that in one respect it is carried through more logically … in the sense that Stirner as an atheist sets the ego above God … whereas Bentham still allows God to remain remote and nebulous above him; that Stirner, in short, is riding on German idealism … whereas Bentham is simply an empiricist.”48 Egoist, altruist, idealist, empiricist, reformer, and “radical fool”: by means of the Auto-Icon, Bentham adds his own voice to the controversy surrounding his own figure and teachings. “Every man is his best biographer,” the philosopher declared and revealed his very essence in the über-ur-image: a three-dimensional “auto-thanatography” with a claim to objectivity.

And how does Bentham introduce himself to us in his tangible autobiography? Above all else as a sociable fellow. Beyond enjoying dinners with friends and chairing various utilitarian clubs, he also hoped for new companions for his Auto-Icon. Other, many, all people should give their bodies to science for the pleasure and edification of the living. All should allow themselves to be auto-iconized. Ancestral halls and city boulevards could be adorned with Auto-Icons. Authentic historical buildings could be constructed around them. A “temple of honour” for august figures and a “temple of dishonour” for traitors (Bentham suggested William Pitt the Younger and King George III) could be furnished with Auto-Icons. As examples of the good as well as the bad, a system illustrating punishment and reward, analogous to the Panopticon’s grandiose stage play of “As If …”: “How instructive would be the vibrations of Auto-Icons between the two temples! The objects of the admiration of one generation might become objects of detestation to another.” Bentham’s “auto-iconic” cosmos is also an allegory of human yearning, a lesson from the principle of utility meant to uplift the human with regard to societal reform. Death—the driving force behind symbolic undoing and the master of socialistic dimensions—would thereby lose its frightful power. It would even make sense, what with the poor and rich enjoying the same chance at auto-iconic representation: “they would indeed ‘meet together’—they would be placed on the same level.” The world of the Auto-Icons would feature on earth that which religious projections of paradise had earmarked for the hereafter.

The Potemkin game of truth and perception is not exhausted in the theater of representation, however, for in utilitarianism, added moral value becomes measurable happiness only through material gain: much like educational progress in the Panopticon, the Auto-Icon’s “reason” is directly equated with economic factors. For instance, Bentham enumerates the spending saved on gravesites, gravestones, and burial taxes. Auto-Icons would also be attractive for the open market. As with the trade in relics and mokomokai heads, the Auto-Icon business would exemplify the laws of the liberal market economy (provided it remain unobstructed by troublesome political regulations). The ethics and historical awareness of the living would directly decide supply and demand, because viewing an auto-iconized personage directly influences consumer interest. Depending on various factors, any given Auto-Icon might be worth two, three, or even several others. And taken as a whole, this difference ultimately enables a concrete calculation of the dominant societal morality.

Since money and happiness are so closely bound in the realm of the Auto-Icon—as in Bentham’s vision of economic reality—the question of power also presents itself here. Bentham answers this question in the grand conclusion of his text on the Auto-Icon, in which he invites auto-iconized individuals from world history to join the cosmic theater. Bands and wires will puppeteer the made-up figures. Their voices will be imitated, their bodies made to “breathe” by unseen mechanisms: illusion and indistinguishability from reality are needed to dazzle the fickle audience intended to view this stage play—the same audience meant to visit the Panopticon. Bentham designated “Bentham” the master of ceremonies. “He” enters the stage to introduce the dramatis personae. “He” seeks learned discussion on morality, ethics, justice, the state, law, logic, architecture, grammar. “Socrates,” “Aristotle,” “Plato,” “Cicero,” “Saint Paul,” “Helvétius,” “Etienne Dumont,” “Euclid,” “Newton,” “Laplace,” “Francis Bacon,” “John Locke,” “Montesquieu,” “d’Alembert,” “Vitruvius,” “Samuel Bentham,” “some important Italian architect,” “Napoleon Bonaparte”: they all stand on stage, waiting to be questioned by “Bentham,” the solicitous emcee, the choreographer of his own apotheosis. “Bentham”—“the sage of the 1830th year after the Christian era”—outlines for “Aristotle” the advancements of the philosophy of happiness at the birth of a better world. “Bentham” pays homage to “Bacon,” gardener of the “encyclopedic tree,” where world knowledge and reason dovetail for the benefit of humankind. “Bentham” introduces “Bacon” to his correspondent “d’Alembert,” the cultivator of this plant, whose golden fruits—“as if reared in the garden of the Hespirides”—Bentham had been privileged to harvest.

This major drama far surpasses the moral weight of the presentations in the Panopticon: “Bentham” delivers the triumphant message of human salvation through utilitarianism around the world. He does, however, require audience participation. At the end of the presentation, the viewers—gathered here on a “Quasi-hadji,” a pilgrimage toward the greatest happiness principle—are to name the quasi-sacred Auto-Icon the winner as the most important Auto-Icon of all. They are to vote (like delegates of a united party at a congress where one can picture the reanimated Auto-Icons of Lenin and Mao in attendance) on “Bentham’s” suggestion, which posits: of all the philosophers, wouldn’t the actual savior have to be … Bentham?

Is not Bentham as good as Mahomet was? In this or that, however distant, age, will he not have done as much good as Mahomet will have done evil to mankind? But earlier than the last day of the earth, what will be the last day of the reign of the greatest-happiness principle? Here ends reverie—here ends the waking dream.49

Bentham’s sense of mission was born of an era that venerated intellectuals, that looked to them to flood the earth with wisdom and the light of reason. Philosophers set trends; they were celebrated and courted like stars and exercised influence to the point of revolution. “Those two men have ruined France,” Louis XVI said of Rousseau and Voltaire.50 In life, Bentham was unable to meet the expectations built up by the luminaries. His Auto-Icon, however, is his triumphator. In the court of public opinion, it helps Bentham claim his self-declared right as the “legislator of the world.” The lines between stage play and viewers dissolve: from London, the new Mecca, the Auto-Icon oversees the spread of a new world religion. It codifies a constitution that is valid the world over, thanks to universal human nature. “Bentham” thus establishes a new order on the basis of eternal laws: “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do.” In this new realm, established around the primacy of economics, a certain force is finally elevated to its rightful spot, a force that seeks—and, according to doctrine, creates—goodness. Because everyone is in search of happiness. And it is complemented by something that magically increases happiness: money.