Debunking the Deniers

T he word debunking has negative connotations for most people, yet when you are presenting answers to claims of an extraordinary nature (and Holocaust denial surely qualifies), then debunking serves a useful purpose. There is, after all, a lot of bunk to be debunked. But I am attempting to do far more than this. In the process of debunking the deniers, I demonstrate how we know that the Holocaust happened, and that it happened in a particular way that most historians have agreed upon.

There is no immutable canon of truth about the Holocaust that can never be altered, as many deniers believe. When you get into the study of the Holocaust, and especially when you start attending conferences and lectures and tracking the debates among Holocaust historians, you discover that there is plenty of infighting about the major and minor points of the Holocaust. The brouhaha over Daniel Goldhagen’s 1996 book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, in which he argued that “ordinary” Germans and not just Nazis participated in the Holocaust, is testimony to the fact that Holocaust historians are anything but settled on exactly what happened, when, why, and how. Nonetheless, an abyss lies between the points that Holocaust historians are debating and those that Holocaust deniers are promoting—their denial of intentional genocide based primarily on race, of programmatic use of gas chambers and crematoria for mass murder, and of the killing of five to six million Jews.

Before addressing the three main axes of Holocaust denial, let us look for a moment at the deniers’ methodology, their modes of argument. Their fallacies of reasoning are eerily similar to those of other fringe groups, such as creationists.

1. They concentrate on their opponents’ weak points, while rarely saying anything definitive about their own position. Deniers emphasize the inconsistencies between eyewitness accounts, for example.

2. They exploit errors made by scholars who are making opposing arguments, implying that because a few of their opponents’ conclusions were wrong, all of their opponents’ conclusions must be wrong. Deniers point to the human soap story, which has turned out to be a myth, and talk about “the incredible shrinking Holocaust” because historians have reduced the number killed at Auschwitz from four million to one million.

3. They use quotations, usually taken out of context, from prominent mainstream figures to buttress their own position. Deniers quote Yehuda Bauer, Raul Hilberg, Arno Mayer, and even leading Nazis.

4. They mistake genuine, honest debates between scholars about certain points within a field for a dispute about the existence of the entire field. Deniers take the intentionalist-functionalist debate about the development of the Holocaust as an argument about whether the Holocaust happened or not.

5. They focus on what is not known and ignore what is known, emphasize data that fit and discount data that do not fit. Deniers concentrate on what we do not know about the gas chambers and disregard all the eyewitness accounts and forensic tests that support the use of gas chambers for mass murder.

Because of the sheer quantity of evidence about the Holocaust—so many years and so much of the world involved, thousands of accounts and documents, millions of bits and pieces—there is enough evidence that some parts can be interpreted as supporting the deniers’ views. The way that deniers treat testimony from the postwar Nuremberg trials of Nazis is typical of their handling of evidence. On the one hand, deniers dismiss the Nuremberg confessions as unreliable because it was a military tribunal run by the victors. The evidence, Mark Weber claims, “consists largely of extorted confessions, spurious testimonies, and fraudulent documents. The postwar Nuremberg trials were politically motivated proceedings meant more to discredit the leaders of a defeated regime than to establish truth” (1992, p.201). Neither Weber nor anyone else has proven that most of the confessions were extorted, spurious, or fraudulent. But even if the deniers were able to prove that some of them were, this does not mean that they all were.

On the other hand, deniers cite Nuremberg trial testimony whenever it supports their arguments. For example, although deniers reject the testimony of Nazis who said there was a Holocaust and they participated in it, deniers accept the testimony of Nazis such as Albert Speer who said they knew nothing about it. But even here, deniers shy away from a deeper analysis. Speer indeed stated at the trials that he did not know about the extermination program. But his Spandau diary speaks volumes:

December 20, 1946. Everything comes down to this: Hitler always hated the Jews; he made no secret of that at any time. He was capable of tossing off quite calmly, between the soup and the vegetable course, “I want to annihilate the Jews in Europe. This war is the decisive confrontation between National Socialism and world Jewry. One or the other will bite the dust, and it certainly won’t be us.” So what I testified in court is true, that I had no knowledge of the killings of Jews; but it is true only in a superficial way. The question and my answer were the most difficult moment of my many hours on the witness stand. What I felt was not fear but shame that I as good as knew and still had not reacted; shame for my spiritless silence at the table, shame for my moral apathy, for so many acts of repression. (1976, p.27)

In addition, Matthias Schmidt, in Albert Speer: The End of a Myth, details Speer’s activities in support of the Final Solution. Among other things, Speer organized the confiscation of 23,765 apartments from Jews in Berlin in 1941; he knew of the deportation of more than 75,000 Jews to the east; he personally inspected the Mauthausen concentration camp, where he ordered a reduction of construction materials and redirected supplies that were needed elsewhere; and in 1977 he told a newspaper reporter, “I still see my guilt as residing chiefly in the approval of the persecution of the Jews and the murder of millions of them” (1984, pp.181-198). Deniers cite Speer’s Nuremberg testimony and ignore all Speer’s elaborations about that testimony.

No matter what we wish to argue, we must bring to bear additional evidence from other sources that corroborates our conclusions. Historians know that the Holocaust happened by the same general method that scientists in such historical fields as archeology or paleontology use—through what William Whewell called a “consilience of inductions,” or a convergence of evidence. Deniers seem to think that if they can just find one tiny crack in the Holocaust structure, the entire edifice will come tumbling down. This is the fundamental flaw in their reasoning. The Holocaust was not a single event. The Holocaust was thousands of events in tens of thousands of places, and is proved by millions of bits of data that converge on one conclusion. The Holocaust cannot be disproved by minor errors or inconsistencies here and there, for the simple reason that it was never proved by these lone bits of data in the first place.

Evolution, for example, is proved by the convergence of evidence from geology, paleontology, botany, zoology, herpetology, entomology, biogeography, anatomy, physiology, and comparative anatomy. No one piece of evidence from these diverse fields says “evolution” on it. A fossil is a snapshot. But when a fossil in a geological bed is studied along with other fossils of the same and different species, compared to species in other strata, contrasted to modern organisms, juxtaposed with species in other parts of the world, past and present, and so on, it turns from a snapshot into a motion picture. Evidence from each field jumps together to a grand conclusion—evolution. The process is no different in proving the Holocaust. Here is the convergence of proof:

Written documents: Hundreds of thousands of letters, memos, blueprints, orders, bills, speeches, articles, memoirs, and confessions.

Eyewitness testimony: Accounts from survivors, Kapos, Sonderkommandos, SS guards, commandants, local townspeople, and even upper-echelon Nazis who did not deny the Holocaust.

Photographs: Official military and press photographs and films, civilian photographs, secret photographs taken by prisoners, aerial photographs, and German and Allied film footage.

Physical evidence: Artifacts found at the sites of concentration camps, work camps, and death camps, many of which are still extant in varying degrees of originality and reconstruction.

Demographics: All those people who the deniers claim survived the Holocaust are missing.

Holocaust deniers ignore this convergence of evidence. They pick out what suits their theory and dismiss or avoid the rest. Historians and scientists do this too, but there is a difference. History and science have self-correcting mechanisms whereby one’s errors are “revised” by one’s colleagues in the true sense of the word. Revision is the modification of a theory based on new evidence or a new interpretation of old evidence. Revision should not be based on political ideology, religious conviction, or other human emotions. Historians are humans with emotions, of course, but they are the true revisionists because eventually the collective science of history separates the emotional chaff from the factual wheat.

Let us examine how the convergence of evidence works to prove the Holocaust, and how deniers select or twist the data to support their claims. We have an account by a survivor who says he heard about the gassing of Jews while he was at Auschwitz. The denier says that survivors exaggerate and that their memories are unsound. Another survivor tells another story different in details but with the core similarity that Jews were gassed at Auschwitz. The denier claims that rumors were floating throughout the camps and many survivors incorporated them into their memories. An SS guard confesses after the war that he actually saw people being gassed and cremated. The denier claims that these confessions were forced out of the Nazis by the Allies. But now a member of the Sonderkommando—a Jew who had helped the Nazis move dead bodies from the gas chambers and into the crematoria—says he not only heard about it and not only saw it happening, he had actually participated in the process. The denier explains this away by saying that the Sonderkommando accounts make no sense—their figures of numbers of bodies are exaggerated and their dates incorrect. What about the camp commandant, who confessed after the war that he not only heard, saw, and participated in the process but orchestrated it? He was tortured, says the denier. But what about his autobiography, written after his trial, conviction, and sentencing to death, when he had nothing to gain by lying? No one knows why people confess to ridiculous crimes, explains the denier, but they do.

No single testimony says “Holocaust” on it. But woven together they make a pattern, a story that holds together, while the deniers’ story unravels. Instead of the historian having to present “just one proof,” the denier must now disprove six pieces of historical data, with six different methods of disproof.

But there is more. We have blueprints of gas chambers and crematoria. Those were used strictly for delousing and body disposal, claims the denier; and thanks to the Allied war against Germany, the Germans were never given the opportunity to deport the Jews to their own homeland and instead had to put them into overcrowded camps where disease and lice were rampant. What about the huge orders for Zyklon-B gas? It was used strictly for delousing all those diseased inmates. What about those speeches by Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, Hans Frank, and Joseph Goebbels talking about the “extermination” of the Jews? Oh, they really meant “rooting out,” as in deporting them out of the Reich. What about Adolf Eichmann’s confession at his trial? He was coerced. Hasn’t the German government confessed that the Nazis attempted to exterminate European Jewry? Yes, but they lied so they could rejoin the family of nations.

Now the denier must rationalize no less than fourteen different bits of evidence that converge to a specific conclusion. But the consilience continues. If six million Jews did not die, where did they go? They are in Siberia and Peoria, Israel and Los Angeles, says the denier. But why can’t they find each other? They do—haven’t you heard the stories of long-separated siblings making contact with one another after many decades? What about the photos and newsreels of the liberation of the camps with all those dead bodies and starving inmates? Those people were well taken care of until the end of the war when the Allies were mercilessly bombing German cities, factories, and supply lines, thus preventing food from reaching the camps; the Nazis tried valiantly to save their prisoners but the combined strength of the Allies was too much. But what about all the accounts by prisoners of the brutality of the Nazis—the random shootings and beatings, the deplorable conditions, the freezing temperatures, the death marches, and so on? That is the nature of war, replies the denier. The Americans interned Japanese-Americans and Japanese nationals in camps. The Japanese imprisoned Chinese. The Russians tortured Poles and Germans. War is hell. The Nazis were no different from anyone else.

We are now up to eighteen sets of evidence all converging toward one conclusion. The denier chips away at them all, determined not to give up his belief system. He is relying on what might be called post hoc rationalization—after-the-fact reasoning to justify contrary evidence—and then on demanding that the Holocaust historian disprove each of his rationalizations. But the convergence of positive evidence supporting the Holocaust means that the historian has already met the burden of proof, and when the denier demands that each piece of evidence independently prove the Holocaust he is ignoring the fact that no historian ever claimed that one piece of evidence proves the Holocaust or anything else. We must examine the evidence as part of a whole, and when we do so the Holocaust can be regarded as proven.

The first major axis of Holocaust denial is that genocide based primarily on race was not intended by Hitler and his followers.

Deniers begin at the top, so I will too. In his 1977 Hitler’s War, David Irving argued that Hitler did not know about the Holocaust. Shortly after, he put his money where his mouth is, promising to pay $1,000 to anyone who could produce documentary proof—specifically, a written document—that Hitler ordered the Holocaust. In a classic example of what I call the snapshot fallacy—taking a single frame out of a historical film—Irving reproduced, on p. 505 of Hitler’s War, Himmler’s telephone notes of November 30, 1941, when the SS chief telephoned Reinhard Heydrich (deputy chief of the Reichssicherheitshaupamt [Head Office for Reich Security, or RSHA, of the SS]) “from Hitler’s bunker at the Wolf’s Lair, ordering that there was to be ‘no liquidation’ of Jews.” From this, Irving concluded that “the Führer had ordered that the Jews were not to be liquidated” (1977, p.504).

But we must see the snapshot in the context of the frames around it. As Raul Hilberg pointed out, in its entirety, the log entry says, “Jewish transport from Berlin. No liquidation.” It was in reference to one particular transport, not all Jews. And, says Hilberg, “that transport was liquidated! That order was either ignored, or it was too late. The transport had already arrived in Riga [capital of Latvia] and they didn’t know what to do with these thousand people so they shot them that very same evening” (1994). Moreover, for Hitler to veto an order for liquidation implies that liquidation was something that was ongoing. To that extent, David Irving’s $1,000 challenge and Robert Faurisson’s demand for “just one proof” are met. If Jews were not being exterminated, why would Hitler feel the need to halt the extermination of a particular transport? And this entry also proves that it was Hitler, and not Himmler or Goebbels, who ordered the Holocaust. As Speer observed regarding Hitler’s role: “I don’t suppose he had much to do with the technical aspects, but even the decision to proceed from shooting to gas chambers would have been his, for the simple reason, as I know only too well, that no major decisions could be made about anything without his approval” (in Sereny 1995, p.362). As Yisrael Gutman noted, “Hitler interfered in all main decisions with regard to the Jews. All the people around Hitler came with their plans and initiatives because they knew that Hitler was interested [in solving the ‘Jewish question’] and they wanted to please him and be the first to realize his intentions and his spirit” (1996).

Whether or not there was a specific order from Hitler for the extermination of the Jews does not matter, then, because it did not need to be spelled out. The Holocaust “was not so much a product of laws and commands as it was a matter of spirit, of shared comprehension, of consonance and synchronization” (Hilberg 1961, p.55). This spirit was made plain in his speeches and writings. From his earliest political ramblings to the final Götterdämmerung of the end in his Berlin bunker, Hitler had it in for Jews. On April 12, 1922, in a speech given in Munich and later published in the newspaper Völkischer Beobachter, he told his audience, “The Jew is the ferment of the decomposition of people. This means that it is in the nature of the Jew to destroy, and he must destroy, because he lacks altogether any idea of working for the common good. He possesses certain characteristics given to him by nature and he never can rid himself of those characteristics. The Jew is harmful to us” (in Snyder 1981, p.29). Twenty-three years later (1922–1945), with his world collapsing around him, Hitler said, “Against the Jews I fought open-eyed and in view of the whole world. … I made it plain that they, this parasitic vermin in Europe, will be finally exterminated” (February 13, 1945; in Jäckel 1993, p.33), and “Above all I charge the leaders of the nation and those under them to scrupulous observance of the laws of race and to merciless opposition to the universal poisoner of all peoples, International Jewry” (April 29, 1945; in Snyder 1981, p.521).

In between, Hitler made hundreds of similar statements. In a speech given January 30, 1939, for example, he said, “Today I want to be a prophet once more: If international finance Jewry inside and outside of Europe should succeed once more in plunging nations into another world war, the consequence will not be the Bolshevization of the earth and thereby the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe” (in Jäckel 1989, p.73). Hitler even told the Hungarian head of state, “In Poland this state of affairs has been … cleared up: if the Jews there did not want to work, they were shot. If they could not work, they were treated like tuberculosis bacilli with which a healthy body may become infected. This is not cruel if one remembers that even innocent creatures of nature, such as hares and deer when infected, have to be killed so that they cannot damage others. Why should the beasts who wanted to bring us Bolshevism be spared more than these innocents?” (in Sereny 1995, p.420). How many more quotes do we need to prove that Hitler ordered the Holocaust—a hundred, a thousand, ten thousand?

David Irving and other deniers make it sound like these speeches do not indicate a smoking gun, by playing a clever game of semantics with the word ausrotten, which according to modern dictionaries means “to exterminate, extirpate, or destroy.” This word can be found in numerous Nazi speeches and documents referring to the Jews. But Irving insists that ausrotten really means “stamping or rooting out,” arguing that “the word ausrotten means one thing now in 1994, but it meant something very different in the time Adolf Hitler uses it.” Yet a check of historical dictionaries shows that ausrotten has always meant “to exterminate.” Irving’s rejoinder provides another example of post hoc rationalization:

Different words mean different things when uttered by different people. What matters is what that word meant when uttered by Hitler. I would first draw attention to the famous memorandum on the Four-Year Plan of August 1936. In that Adolf Hitler says, “We are going to have to get our armed forces in a fighting state within four years so that we can go to war with the Soviet Union. If the Soviet Union should ever succeed in overrunning Germany it will lead to the ausrotten of the German people.” There’s that word. There is no way that Hitler can mean the physical liquidation of 80 million Germans. What he means is that it will lead to the emasculation of the German people as a power factor. (1994)

I then pointed out that, at a December 1944 conference regarding the Ardennes attack against the Americans, Hitler ordered his generals “to ausrotten them division by division.” Was Hitler giving the order to transport the Americans out of the Ardennes division by division? Irving countered:

Compare that with a speech he made in August 1939, in which he says, with regard to Poland, “we are going to destroy the living forces of the Polish Army.” This is the job of any commander—you have to destroy the forces facing you. How you destroy them, how you “take them out” is probably a better phrase, is immaterial. If you take those pawns off the chess board they are gone. If you put the American forces in captivity they are equally neutralized whether they are in captivity or dead. And that’s what the word ausrotten means there. (1994)

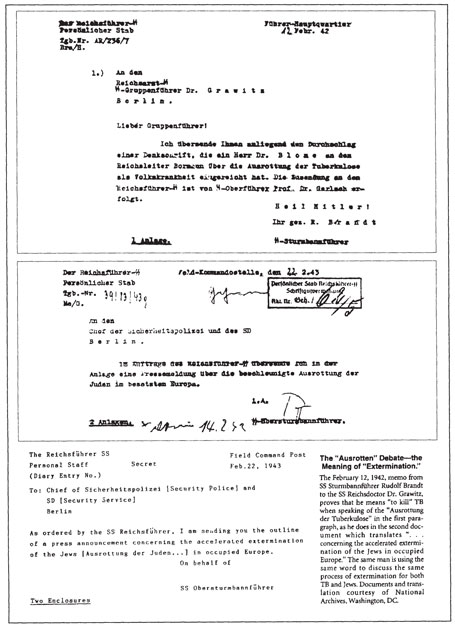

But what about Rudolf Brandt’s use of the word? To SS Gruppenführer Dr. Grawitz of the SS Reichsarzt in Berlin, SS Sturmbannführer Brandt wrote concerning “the Ausrottung of tuberculosis as a disease affecting the nation.” A year later, now an SS Obersturmbannführer, he wrote to Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Heydrich’s successor as chief of RSHA, “I am sending you the outline of a press announcement concerning the accelerated Ausrottung of the Jews in occupied Europe.” The same man is using the same word to discuss the same process for tuberculosis and Jews (see figure 20). What else could ausrotten have meant in these contexts except “extermination”?

And what about Hans Frank’s use of the word? In a speech to a Nazi assembly held on October 7, 1940, Frank summed up his first year of effort as head of the Generalgouvernement of occupied Poland: “I could not ausrotten all lice and Jews in only one year. But in the course of time, and if you help me, this end will be attained” (Nuremberg Doc. 3 363-PS, p.891). On December 16, 1941, Frank addressed a government session at the office of the governor of Krakau in conjunction with the upcoming Wannsee Conference:

Currently there are in the Government Generalship approximately 2.5 million, and together with those who are kith and kin and connected in all kinds of ways, we now have 3.5 million Jews. We cannot shoot these 3.5 million Jews, nor can we poison them, yet we will have to take measures which will somehow lead to the goal of annihilation, and that will be done in connection with the great measures which are to be discussed together with the Reich. The territory of the General Government must be made free of Jews, as is the case in the Reich. Where and how this will happen is a matter of the means which must be used and created, and about whose effectiveness I will inform you in due time. (Original document and translation, National Archives, Washington, D.C., T922, PS 2233)

FIGURE 20:

Rudolf Brandt writes about (top) “die Ausrottung die Tuberkulose” to SS Gruppenführer Dr. Grawitz of the SS Reichsarzt, February 12, 1942; and (bottom) “die beschleunigte Ausrottung der Juden” to Ernst Kaltenbrunner, chief of RSHA, February 22, 1943. Ausrottung means “extermination.” [Documents and translation courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C.]

If the Final Solution meant deportation out of the Reich, as Irving and other deniers claim, does this mean that Frank was planning to send lice out of Poland on trains? And why would Frank be making references to the extermination of Jews through means other than shooting or poisoning?

And then there are entries from the diary of Joseph Goebbels, Gauleiter (General) of Berlin, Reich Minister of Propaganda, and Reich Plenipotentiary for total war effort, such as these:

August 8, 1941, concerning the spread of spotted typhus in the Warsaw ghetto: “The Jews have always been the carriers of infectious diseases. They should either be concentrated in a ghetto and left to themselves or be liquidated, for otherwise they will infect the populations of the civilized nations.”

August 19, 1941, after a visit to Hitler’s headquarters: “The Führer is convinced his prophecy in the Reichstag is becoming a fact: that should Jewry succeed in again provoking a new war, this would end with their annihilation. It is coming true in these weeks and months with a certainty that appears almost sinister. In the East the Jews are paying the price, in Germany they have already paid in part and they will have to pay more in the future.” (Broszat 1989, p.143)

Himmler also talks about the ausrotten of the Jews, and again there is evidence that negates the deniers’ definition of that word. For example, in a lecture on the history of Christianity given in January 1937, Himmler told his SS Gruppenführers, “I have the conviction that the Roman emperors, who exterminated [ausrotteten] the first Christians, did precisely what we are doing with the communists. These Christians were at that time the vilest scum, which the city accommodated, the vilest Jewish people, the vilest Bolsheviks there were” (Padfield 1990, p.188). In June 1941, Himmler informed Rudolf Hoess, the commandant of Auschwitz, that Hitler had ordered the Final Solution (Endlösung) of the Jewish question, and that Hoess would play a major role at Auschwitz:

It is a hard, tough task which demands the commitment of the whole person without regard to any difficulties that may arise. You will be given details by Sturmbannführer Eichmann of the RSHA who will come to see you in the near future. The department taking part will be informed at the appropriate time. You have to maintain the strictest silence about this order, even to your superiors. The Jews are the eternal enemies of the German people and must be exterminated. All Jews we can reach now, during the war, are to be exterminated without exception. If we do not succeed in destroying the biological basis of Jewry, some day the Jews will annihilate the German Volk [people]. (Padfield 1990, p.334)

Himmler made many similarly damning speeches. One of the most notorious is the October 4, 1943, speech to the SS Gruppenführer in Poznan (Posen), which was recorded on a red oxide tape. Himmler was lecturing from notes, and early in the talk he stopped the tape recorder to make sure it was working. He then continued, knowing he was being recorded, and spoke for over three hours on a range of subjects, including the military and political situation, the Slavic peoples and racial blends, how the racial superiority of Germans would help them win the war, and the like. Two hours into the speech, Himmler began to talk about the bloody 1934 purges of traitors in the Nazi Party and “the extermination of the Jewish people.”

I also want to refer here very frankly to a very difficult matter. We can now very openly talk about this among ourselves, and yet we will never discuss this publicly. Just as we did not hesitate on June 30, 1934, to perform our duty as ordered and put comrades who had failed up against the wall and execute them, we also never spoke about it, nor will we ever speak about it. Let us thank God that we had within us enough self-evident fortitude never to discuss it among us, and we never talked about it. Every one of us was horrified, and yet every one clearly understood that we would do it next time, when the order is given and when it becomes necessary.

I am now referring to the evacuation of the Jews, to the extermination of the Jewish people. This is something that is easily said: “The Jewish people will be exterminated,” says every Party member, “this is very obvious, it is in our program—elimination of the Jews, extermination, will do.” And then they turn up, the brave 80 million Germans, and each one has his decent Jew. It is of course obvious that the others are pigs, but this particular one is a splendid Jew. But of all those who talk this way, none had observed it, none had endured it. Most of you here know what it means when 100 corpses lie next to each other, when 500 lie there or when 1,000 are lined up. To have endured this and at the same time to have remained a decent person—with exceptions due to human weaknesses—has made us tough. This is an honor roll in our history which has never been and never will be put in writing, because we know how difficult it would be for us if we still had Jews as secret saboteurs, agitators and rabble rousers in every city, what with the bombings, with the burden and with the hardships of the war. If the Jews were still part of the German nation, we would most likely arrive now at the state we were at in 1916/17. (Original document and translation, National Archives, Washington, D.C., PS Series 1919, pp.64-67)

Irving’s response to this quote was interesting:

Irving: I have a later speech he made on January 26, 1944, in which he is speaking to the same audience rather more bluntly about the ausrotten of Germany’s Jews, when he announced that they had totally solved the Jewish problem. Most of the listeners sprang to their feet and applauded. “We were all there in Poznan,” recalled a Rear Admiral, “when that man [Himmler] told us how he’d killed off the Jews. I can still recall precisely how he told us. ‘If people ask me,’ said Himmler, ‘why did you have to kill the children too, then I can only say I am not such a coward that I leave for my children something I can do myself.’” Quite interesting—this is an Admiral afterwards recording this in British captivity without realizing he was being tape recorded, which is a very good summary of what Himmler actually said.

Shermer: That sounds to me like he means to kill Jews, not just transport them out of the Reich.

Irving: I agree, Himmler said that. He actually said, “We’re wiping out the Jews. We’re murdering them. We’re killing them.”

Shermer: What does that mean other than what it sounds like?

Irving: I agree, Himmler is admitting what I said happened to the 600,000. But, and this is the important point, nowhere does Himmler say, “We are killing millions.” Nowhere does he even say we are killing hundreds of thousands. He is talking about solving the Jewish problem, about having to kill off women and children too. (1994)

Irving, once again, has fallen into the fallacy of ad hoc rationalization. Since Himmler never exactly said millions, therefore he really meant thousands. But, please note, Himmler never said thousands either. Irving is inferring what he wants to infer. The actual numbers come from other sources, which, in conjunction with Himmler’s speeches and many other pieces of evidence, converge on the conclusion that he meant millions would be killed. And millions were killed.

Finally, there is telling evidence about the extermination of Jews from lower down in the ranks. The Einsatzgruppen were mobile SS and police units for special missions in occupied territories. Their mandate included rounding up and killing Jews and other unwanted persons in towns and villages prior to occupation by Germans. For the winter of 1941–1942, for example, Einsatzgruppe A reported 2,000 Jews killed in Estonia, 70,000 in Latvia, 136,421 in Lithuania, and 41,000 in Belorussia. On November 14, 1941, Einsatzgruppe B reported 45,467 shootings, and on July 31, 1942, the governor of Belorussia reported that 65,000 Jews were killed during the previous two months. Einsatzgruppe C estimated they had killed 95,000 by December 1941, and Einsatzgruppe D reported on April 8, 1942, a total of 92,000 killed. The grand total is 546,888 dead in less than one year.

Numerous eyewitness accounts from members of the Einsatzgruppen can be found in “The Good Old Days”: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders (Klee, Dressen, and Riess 1991). For example, on Sunday, September 27, 1942, SS Obersturmführer Karl Kretschmer wrote to “My dear Soska,” his wife. He apologizes for not writing more, is feeling ill and in “low spirits” because “what you see here makes you either brutal or sentimental.” His “gloomy mood,” he explains, is caused by “the sight of the dead (including women and children).” Which dead? Dead Jews, who deserve to die: “As the war is in our opinion a Jewish war, the Jews are the first to feel it. Here in Russia, wherever the German soldier is, no Jew remains. You can imagine that at first I needed some time to get to grips with this.” In a subsequent letter, not dated, he explains to his wife that “there is no room for pity of any kind. You women and children back home could not expect any mercy or pity if the enemy got the upper hand. For that reason we are mopping up where necessary but otherwise the Russians are willing, simple and obedient. There are no Jews here any more.” Finally, on October 19, 1942, in a letter signed “You deserve my best wishes and all my love, Your Papa,” Kretschmer provides a paradigmatic example of what Hannah Arendt meant by the banality of evil:

If it weren’t for the stupid thoughts about what we are doing in this country, the Einsatz here would be wonderful, since it has put me in a position where I can support you all very well. Since, as I already wrote to you, I consider the last Einsatz to be justified and indeed approve of the consequences it had, the phrase: “stupid thoughts” is not strictly accurate. Rather it is a weakness not to be able to stand the sight of dead people; the best way of overcoming it is to do it more often. Then it becomes a habit, (pp.163-171)

There may not have been a written order, but the Nazi’s intentionality of genocide primarily by race was not only clear but also known rather widely.

For several decades following the war, historians debated the “intentionalism” versus the “functionalism” of the Holocaust. Intentionalists argued that Hitler intended the mass extermination of the Jews from the early 1920s, that Nazi policy in the 1930s was programmed toward this end, and that the invasion of Russia and the quest for Lebensraum were directly planned and linked to the Final Solution of the Jewish question. Functionalists, by contrast, argued that the original plan for the Jews was expulsion and that the Final Solution evolved as a result of the failed war against Russia. Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg, however, feels that these are artificial distinctions: “In reality it is more complicated than either of these interpretations. I believe Hitler gave a plenary order, but that order was itself the end product of a process. He said many things along the way which encouraged the bureaucracy to think along certain lines and to take initiatives. But on the whole I would say that any kind of systematic shooting, particularly of young children or very old people, and any kind of gassing, required Hitler’s order” (1994).

Under the weight of historical evidence, intentionalism has not survived the test of time. The immediate reason, as outlined by Ronald Headland, was dawning recognition of “the competitive, almost anarchical and decentralized quality of the National Socialist system, with its rivalries, its ubiquitous personality politics, and the ever-present pursuit of power among its agencies… . Perhaps the greatest merit of the functionalist approach has been the extent to which it has delineated the chaotic character of the Third Reich and the often great complexity of factors involved in the decision-making process” (1992, p.194). But the ultimate reason for acceptance of the functionalist view is that events, especially an event as complicated and contingent as the Holocaust, rarely unfold as historical actors plan. Even the famous Wannsee Conference of January 1942, at which the Nazis confirmed the implementation of the Final Solution, has been shown by Holocaust scholar Yehuda Bauer to be just one more contingent step down the road from original expulsion to final extermination. This is backed up by the existence of a realistic plan to deport the Jews to the island of Madagascar and attempts to trade Jews for cash after the Wannsee Conference. Bauer quotes Himmler’s note to himself of December 10, 1942: “I have asked the Führer with regard to letting Jews go in return for ransom. He gave me full powers to approve cases like that, if they really bring in foreign currency in appreciable quantities from abroad” (1994, p.103).

Does this discount the intentionality of the Nazis to exterminate the Jews? No, says Bauer, but it demonstrates the complexity of history and the expediency of the moment:

In prewar Germany, emigration suited the circumstances best, and when that was neither speedy enough or complete enough, expulsion—preferably to some “primitive” place, uninhabited by true Nordic Aryans, the Soviet Union or Madagascar—was the answer. When expulsion did not work either, and the prospect of controlling Europe and, through Europe, the world arose in late 1940 and early 1941, the murder policy was decided on, quite logically, on the basis of Nazi ideology. All these policies had the same aim: removal. (Bauer 1994, pp.252-253)

The functional sequence went from eviction of the Jews from German life (including confiscation of most of their property and homes), to concentration and isolation (often under overcrowded and filthy conditions, leading to disease and death), to economic exploitation (unpaid forced labor that often involved overwork, starvation, and death), to extermination. Gutman agrees with this contingent interpretation: “The Final Solution was an operation that started from the bottom, from a local basis, with a kind of escalation from place to place, until it was a comprehensive event. I don’t know if I would call it a plan. I say it was a blueprint. Physical destruction was the outcome of a series of steps and attacks against the Jews” (1996).

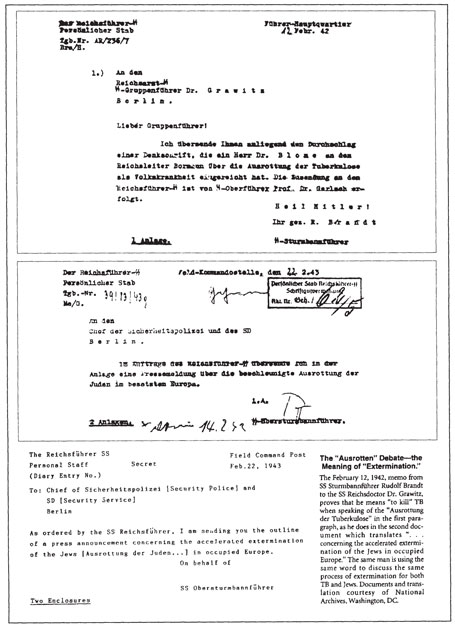

FIGURE 21:

Holocaust feedback loop. Interaction of internal psychological states and external social conditions may produce a genocidal feedback loop.

The Holocaust can be modeled as a feedback loop fed by the flow of information, intentions, and actions (figure 21). From the time the Nazis took power in 1933 and began passing legislation against Jews, to Kristallnacht and other acts of violence against Jews, to the deportation of Jews to ghettos and labor camps, to the extermination of Jews in labor and death camps, we can see at work such internal psychological components as xenophobia, racism, and violence, interacting with such external social components as a rigid hierarchical social structure, a strong central power, intolerance of diversity (religious, racial, ethnic, sexual, or political), built-in mechanisms of violence to handle dissenters, regular use of violence to enforce laws, and a low regard for civil liberties. Christopher Browning nicely summed up how this feedback loop worked in the Third Reich:

In short, for Nazi bureaucrats already deeply involved in and committed to “solving the Jewish question,” the final step to mass murder was incremental, not a quantum leap. They had already committed themselves to a political movement, to a career, and to a task. They lived in an environment already permeated by mass murder. This included not only programs with which they were not directly involved, like the liquidation of the Polish intelligentsia, the gassing of the mentally ill and handicapped in Germany, and then on a more monumental scale the war of destruction in Russia. It also included wholesale killing and dying before their very eyes, the starvation in the ghetto of Lodz and the punitive expeditions and reprisal shooting in Serbia. By the very nature of their past activities, these men had articulated positions and developed career interests that inseparably and inexorably led to a similar murderous solution to the Jewish question. (1991, p.143)

History addresses the complexities of human acts, but within these complexities are simplicities of essences. Hitler, Himmler, Goebbels, Frank, and other Nazis were quite serious in their intention to solve the Jewish question, mainly because they were virulently antisemitic. They may have begun with resettlement, but they ended up at genocide because history’s final pathways are determined by the functions of any given moment interacting with the intentions that came before. Hitler and his followers built out of their functions and intentions a road that led to camps, gas chambers and crematoria, and the extermination of millions.

The second major axis of Holocaust denial is that gas chambers and crematoria were not used for mass killings. How can anyone deny that the Nazis used gas chambers and crematoria? After all, these facilities still exist in many camps. To debunk the deniers can’t you just go there and see for yourself? What about the evidence? In 1990, Arno Mayer noted in Why Did the Heavens Not Darken? that “sources for the study of the gas chambers are at once rare and unreliable.” Deniers cite this sentence as vindication of their position. Mayer is a highly respected diplomatic historian at Princeton University, so one can see why deniers might be delighted by having him seemingly reinforce what they have always believed. But the entire paragraph reads:

Sources for the study of the gas chambers are at once rare and unreliable. Even though Hitler and the Nazis made no secret of their war on the Jews, the SS operatives dutifully eliminated all traces of their murderous activities and instrument. No written orders for gassing have turned up thus far. The SS not only destroyed most camp records, which were in any case incomplete, but also razed nearly all killing and cremating installations well before the arrival of Soviet troops. Likewise, care was taken to dispose of the bones and ashes of the victims. (1990, p.362)

Clearly, Mayer is not arguing that gas chambers were not used for mass extermination. Mayer’s paragraph also neatly summarizes why the physical evidence for mass murder is not quite as overwhelmingly obvious as one might expect.

Deniers do not deny the use of gas chambers and crematoria, but they claim that gas chambers were used strictly for delousing clothing and blankets, and crematoria were used solely to dispose of bodies of people who died of “natural” causes in the camps. Before examining the evidence that the Nazis used gas chambers for mass murder in detail, consider in general the convergence of evidence from various sources:

Official Nazi documents: Orders for large quantities of Zyklon-B (the trade name of hydrocyanic acid gas), blueprints for gas chambers and crematoria, and orders for building materials for gas chambers and crematoria.

Eyewitness testimony: Survivor accounts, Jewish Sonderkommando diaries, and confessions of guards and commandants all tell of gas chambers and crematoria being used for mass murder.

Photographs: Photographs not only of the camps but also secret photographs of the burning of bodies at Auschwitz and Allied aerial reconnaissance photographs of prisoners being marched to the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The camps themselves: Buildings and artifacts at the camps and the results of modern forensic tests that point to the use of both gas chambers and crematoria for killing large numbers of people.

No one source by itself proves that gas chambers and crematoria were used for genocide. It is the convergence of these sources that leads inexorably to this conclusion. For example, delivery of Zyklon-B to the camps in accordance with the written orders is corroborated by the remains of Zyklon-B canisters at the camps and by eyewitness accounts of the use of Zyklon-B in the gas chambers.

About the gassings themselves, deniers ask why no extermination victim has given an eyewitness account of an actual gassing (Butz 1976). This is like asking why no one from the killing fields of Cambodia or Stalin’s purges came back to tell tales on their executioners. What we do have are hundreds of eyewitness accounts not only from SS men and Nazi doctors but from Sonderkommandos who dragged the bodies from the gas chambers and into the crematoria. In his Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers, Filip Müller describes the deception and gassing process as follows:

Two of the SS men took up positions on either side of the entrance door. Shouting and wielding their truncheons, like beaters at a hunt, the remaining SS men chased the naked men, women and children into the large room inside the crematorium. A few SS men were leaving the building and the last one locked the entrance door from the outside. Before long the increasing sound of coughing, screaming and shouting for help could be heard from behind the door. I was unable to make out individual words, for the shouts were drowned by knocking and banging against the door, intermingled with sobbing and crying. After some time the noise grew weaker, the screams stopped. Only now and then there was a moan, a rattle, or the sound of muffled knocking against the door. But soon even that ceased and in the sudden silence each one of us felt the horror of this terrible mass death. (1979, pp.33-34)

Once everything was quiet inside the crematorium, Unterscharführer Teuer, followed by Stark, appeared on the flat roof. Both had gas-masks dangling round their necks. They put down oblong boxes which looked like food tins; each tin was labeled with a death’s head and marked Poison! What had been just a terrible notion, a suspicion, was now a certainty: the people inside the crematorium had been killed with poison gas. (p.61)

We also have the confessions of guards. SS Unterscharführer Pery Broad was captured on May 6, 1945, by the British in their zone of occupation in Germany. Broad began work at Auschwitz in 1942 in the “Political Section” and stayed there until the liberation of the camp in January 1945. After his capture, while working as an interpreter for the British, he wrote a memoir that was passed on to the British Intelligence Service in July 1945. In December 1945, he declared under oath that what he wrote was true. On September 29, 1947, the document was translated into English and used at the Nuremberg trials regarding the gas chambers as mechanisms of mass murder. Later in 1947, he was released. When called to testify at a trial of Auschwitz SS men in April 1959, Broad acknowledged his authorship of the memoir, confirmed its validity, and retracted nothing.

I give this context for Broad’s memoir because deniers dismiss damning Nazi confessions as either coerced or made up for bizarre psychological reasons (while accepting without hesitation confessions that support deniers’ views). Broad was never tortured, and he had little to gain and everything to lose by confessing. When given the opportunity to recant, which he certainly could have in the later trial, he did not. Instead, he described in detail the gassing procedure, including the use of Zyklon-B, the early gassing experiments in Block 11 of Auschwitz, and the temporary chambers set up in the two abandoned farms at Birkenau (Auschwitz II), which he correctly called by their jargon name, “Bunkers I and II.” He also recalled the construction of Kremas II, III, IV, and V at Birkenau, and accurately depicted (by comparison with blueprints) the design of the undressing room, gas chamber, and crematorium. Then Broad described the process of gassing in gruesome detail:

The disinfectors are at work… with an iron rod and hammer they open a couple of harmless looking tin boxes, the directions read Cyclon [sic] Vermin Destroyer, Warning, Poisonous. The boxes are filled with small pellets which look like blue peas. As soon as the box is opened the contents are shaken out through an aperture in the roof. Then another box is emptied in the next aperture, and so on. After about two minutes the shrieks die down and change to a low moaning. Most of the men have already lost consciousness. After a further two minutes … it is all over. Deadly quiet reigns… . The corpses are piled together, their mouths stretched open. … It is difficult to heave the interlaced corpses out of the chamber as the gas is stiffening all their limbs, (in Shapiro 1990, p.76)

Deniers point out that Broad’s total of four minutes for the process is at odds with the statements of others, such as Commandant Hoess, who claim it was more like twenty minutes. Because of such discrepancies, deniers dismiss the account entirely. A dozen different accounts give a dozen different figures for time of death by gassing, so deniers believe no one was gassed at all. Does this make sense? Of course not. Obviously, the gassing process would take different amounts of time due to variations in conditions, including the temperature (the rate of hydrocyanic acid gas evaporation from the pellets depends on air temperature), the number of people in the room, the size of the room, and the amount of Zyklon-B poured into the room—not to mention that each observer would perceive time differently. If the time estimates were exactly the same, in fact, we would have to be suspicious that they were all taking their stories from a single account. In this case, discrepancy tends to support the veracity of the evidence.

Compare Broad’s testimony with that of the camp physician, Dr. Johann Paul Kremer:

September 2, 1942. Was present for first time at a special action at 3 A.M. By comparison Dante’s Inferno seems almost a comedy. Auschwitz is justly called an extermination camp!

September 5, 1942. At noon was present at a special action in the women’s camp—the most horrible of all horrors. Hschf. Thilo, military surgeon, was right when he said to me today that we are located here in the anus mundi [anus of the world]. (1994, p.162)

Deniers seize upon the fact that Kremer says “special action,” not “gassing,” but at the trial of the Auschwitz camp garrison in Krakau in December 1947, Kremer specified what he meant by “special action”:

By September 2, 1942, at 3 A.M. I had already been assigned to take part in the action of gassing people. These mass murders took place in small cottages situated outside the Birkenau camp in a wood. The cottages were called “bunkers” in the SS-men’s slang. All SS physicians on duty in the camp took turns to participate in the gassings, which were called Sonderaktion [special action]. My part as physician at the gassing consisted in remaining in readiness near the bunker. I was brought there by car. I sat in front with the driver and an SS hospital orderly sat in the back of the car with oxygen apparatus to revive SS-men, employed in the gassing, in case any of them should succumb to the poisonous fames. When the transport with people who were destined to be gassed arrived at the railway ramp, the SS officers selected from among the new arrivals persons fit to work, while the rest—old people, all children, women with children in their arms and other persons not deemed fit to work—were loaded onto lorries and driven to the gas chambers. There people were driven into the barrack huts where the victims undressed and then went naked to the gas chambers. Very often no incidents occurred, as the SS-men kept people quiet, maintaining that they were to bathe and be deloused. After driving all of them into the gas chamber the door was closed and an SS-man in a gas mask threw the contents of a Cyclon [sic] tin through an opening in the side wall. The shouting and screaming of the victims could be heard through that opening and it was clear that they were fighting for their lives. These shouts were heard for a very short while. (1994, p.162n)

The convergence of Broad’s and Kremer’s accounts—and there are plenty more—provides evidence that the Nazis used gas chambers and crematoria for mass extermination.

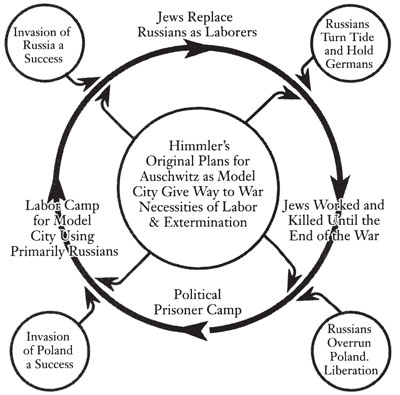

We have hundreds of accounts of survivors describing the unloading and separation process of Jews at Auschwitz, and we have photographs of the process. We also have eyewitness accounts of the Nazis burning bodies in open pits after gassing (the crematoria often broke down), and we have a photograph of such a burning, taken secretly by a Greek Jew named Alex (figure 22). Alter Fajnzylberg, a French Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, recalled how this photograph was obtained:

FIGURE 22:

Open pit burning of bodies at Auschwitz. Sonderkommandos took this picture secretly and smuggled it out of the camp. [Photograph © Yad Vashem. All rights reserved.]

On the day on which the pictures were taken we allocated tasks. Some of us were to guard the person taking the pictures. At last the moment came. We all gathered at the western entrance leading from the outside to the gas chamber of Crematorium V: we could not see any SS men in the watch-tower overlooking the door from above the barbed wire, nor near the place where the pictures were to be taken. Alex, the Greek Jew, quickly took out his camera, pointed it toward a heap of burning bodies, and pressed the shutter. This is why the photograph shows prisoners from the Sonderkommando working at the heap. (Swiebocka 1993, pp.42–43)

Deniers also focus on the lack of photographic proof of gas chamber and crematoria activity in aerial reconnaissance photographs taken of the camps by the Allies. In 1992, denier John Ball actually published an entire book documenting this lack of evidence. The book is a high-quality, slick publication printed on glossy paper in order to hold the detail of the aerial photographs. Ball spent tens of thousands of dollars on the book, did all the layout and typesetting, and even printed the book himself. The project cost him more than just his savings. His wife gave him an ultimatum: her or the Holocaust. He chose the latter. Ball’s book is a response to a 1979 CIA report on the aerial photographs—The Holocaust Revisited: A Retrospective Analysis of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Complex—in which the two authors, Dino A. Brugioni and Robert G. Poirier, present aerial photographs taken by the Allies that they claim prove extermination activities. According to Ball, the photographs were tampered with, marked, altered, faked. By whom? By the CIA itself, in order to match the story as depicted in the television mini-series Holocaust.

Thanks to Dr. Nevin Bryant, supervisor of cartographic applications and image processing applications at Caltech/NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, I was able to get the CIA photographs properly analyzed by people who know what they are looking at from the air. Nevin and I analyzed the photographs using digital enhancement techniques not available to the CIA in 1979. We were able to prove that the photographs had not been tampered with, and we indeed found evidence of extermination activity. The aerial photographs were shot in sequence as the plane flew over the camp (on a bombing run toward its ultimate target—the IG Farben Industrial works). Since the photographs of the camp were taken a few seconds apart, stereoscopic viewing of two consecutive photographs shows movement of people and vehicles and provides better depth perception. The aerial photograph in figure 23 shows the distinctive features of Krema II. Note the long shadow from the crematorium chimney and, on the roof of the adjacent gas chamber at right angles to the crematorium building, note the four staggered shadows. Ball claims these shadows were drawn in, but four small structures that match the shadows are visible on the roof of the gas chamber in figure 24, a picture taken by an SS photographer of the back of Krema II (if you look directly below the chimney of Krema II, you will see two sides of the rectangular underground gas chamber structure protruding a few feet above the ground). This photographic evidence converges nicely with eyewitness accounts describing SS men pouring Zyklon-B pellets through openings in the roof of the gas chamber. The aerial photograph in figure 25 shows a group of prisoners being marched into Krema V for gassing. The gas chamber is at the end of the building, and the crematorium has double chimneys. From the camp’s daily logs, it is clear that these are Hungarian Jews from an RSHA transport, some of whom were selected for work and the rest sent for extermination. (Additional photographs and detailed discussion appear in Shermer and Grobman 1997.)

FIGURE 23:

Aerial photograph of Krema II, August 25, 1944. Note the four staggered shadows on the gas chamber roof in this photograph and compare then to the four small structures visible on the roof of the gas chamber in figure 24. These photographs support eyewitness accounts of Nazis pouring Zyklon-B pellets through the roof of the gas chamber–an example of how separted lines of evidence converge to a single conclusion. [Negative courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C. (Film 3185); enhancement courtesy Nevin Bryant.]

For obvious reasons, there are no photographs recording an actual gassing, and the difficulty with photographic evidence is that any photograph of activity at a camp cannot by itself prove anything, even if it has not been tampered with. One photograph shows Nazis burning bodies at Auschwitz. So what, say deniers. Those are bodies of prisoners who died of natural causes, not of prisoners who were gassed. Several aerial photographs show the details of the Kremas at Birkenau and record prisoners being marched into them. So what, say deniers. The prisoners are going to work to clean up after bodies of people who died of natural causes were burned; or they are going for delousing. Again, it is context and convergence with other evidence that make such photographs telling—and the fact that none of the photographs records activities at variance with the accounts of life in the camps supports the Holocaust and the use of gas chambers and crematoria for mass murder.

FIGURE 24:

Back view of Krema II taken by an SS photographer, 1942. [Photograph © Yad Vashem. All rights reserved.]

The final major axis of Holocaust denial is the number of Jewish victims. Paul Rassinier concluded his Debunking the Genocide Myth: A Study of the Nazi Concentration Camps and the Alleged Extermination of European Jewry by claiming “a minimum of 4,419,908 Jews succeeded in leaving Europe between 1931 and 1945” (1978, p. x) and therefore far fewer than six million Jews died at the hands of the Nazis. Most Holocaust scholars, however, place the total number of Jewish victims between 5.1 and 6.3 million.

While estimates do vary, historians using different methods and different source materials independently arrive at five to six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust. The fact that the estimates vary actually adds credibility; that is, it would be more likely that the numbers were “cooked” if the estimates all came out the same. The fact that the estimates do not come out the same yet all are within a reasonable range of error variance means somewhere between five and six million Jews died in the Holocaust. Whether it is five or six million is irrelevant. It is a large number of people. And it was not just several hundred thousand or “only” one or two million, as some deniers suggest. More accurate estimates will be made in the future as new information arrives from Russia and former Soviet territories. The overall figure, however, is not likely to change by more than a few tens of thousands, and certainly not by hundreds of thousands or millions.

FIGURE 25:

Aerial photograph of prisoners being marched into Krema V, May 31, 1944. [Negative courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C. (Film 3055); enhancement courtesy Nevin Bryant.]

The table below presents estimated Jewish losses in the Holocaust by country. The figures were compiled by a number of scholars, each working in his or her own geographic area of specialty, and then combined by Yisrael Gutman and Robert Rozett for the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. The figures were derived from population demographics, taking the number of Jews registered living in every village, town, and city in Europe, the number reported transported to camps, the number liberated from camps, the number killed in “special actions” by the Einsatzgruppen, and the number remaining alive after the war. The minimum and maximum loss figures represent the range of error variation.

ESTIMATED LOSS OF JEWS IN THE HOLOCAUST

Initial |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

Country |

Jewish Population |

Loss |

Loss |

Austria |

185,000 |

50,000 |

50,000 |

Belgium |

65,700 |

28,900 |

28,900 |

Bohemia and Moravia |

118,310 |

78,150 |

78,150 |

Bulgaria |

50,000 |

0 |

0 |

Denmark |

7,800 |

60 |

60 |

Estonia |

4,500 |

1,500 |

2,000 |

Finland |

2,000 |

7 |

7 |

France |

350,000 |

77,320 |

77,320 |

Germany |

566,000 |

134,500 |

141,500 |

Greece |

77,380 |

60,000 |

67,000 |

Hungary |

825,000 |

550,000 |

569,000 |

Italy |

44,500 |

7,680 |

7,680 |

Latvia |

91,500 |

70,000 |

71,500 |

Lithuania |

168,000 |

140,000 |

143,000 |

Luxembourg |

3,500 |

1,950 |

1,950 |

Netherlands |

140,000 |

100,000 |

100,000 |

Norway |

1,700 |

762 |

762 |

Poland |

3,300,000 |

2,900,000 |

3,000,000 |

Romania |

609,000 |

271,000 |

287,000 |

Slovakia |

88,950 |

68,000 |

71,000 |

Soviet Union |

3,020,000 |

1,000,000 |

1,100,000 |

Total |

9,796,840 |

5,596,029 |

5,860,129 |

SOURCE: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, editor in chief Yisrael Gutman (New York: Macmillan, 1990), p.1799.

Finally, one might ask the denier one simple question: If six million Jews did not die in the Holocaust, where did they all go? The denier will say they are living in Siberia and Kalamazoo, but for millions of Jews to suddenly appear out of the hinterlands of Russia or America or anywhere else is so unlikely as to be nonsensical. The Holocaust survivor who does turn up is a rare find indeed.

There were many millions more killed by the Nazis, including Gypsies, homosexuals, mentally and physically handicapped persons, political prisoners, and especially Russians and Poles, but Holocaust deniers do not worry about the numbers of these dead. This fact has something to do with the widespread lack of attention to non-Jewish victims of the Holocaust, yet it also has something to do with the antisemitic core of Holocaust denial.

Coupled with deniers’ obsession with “the Jews” is an obsession with conspiracies. On the one hand, they deny that the Nazis had a plan (i.e., a conspiracy) to exterminate the Jews. They reinforce this argument by pointing out how extreme conspiratorial thinking can become (à la JFK conspiracy theories). They demand powerful evidence before historians can conclude that Hitler and his followers conspired to exterminate European Jewry (Weber 1994b). Fine. But they cannot then claim, on the other hand, that the idea of the Holocaust was a Zionist conspiracy to obtain reparations from Germany in order to fund the new State of Israel, without meeting their own demands for proof.

As a part this latter argument, deniers claim that if the Holocaust really happened as Holocaust historians say it did, then it would have been widely known during the war (Weber 1994b). It would be as obvious as, say, the D-day landing was. Plus, the Nazis would have discussed their murderous plans among themselves. Well, for obvious reasons, D-day was kept a secret and the D-day landing was not widely known until after it began. Likewise for the Holocaust. It was not something that was casually discussed even between fellow Nazis. Albert Speer, in fact, wrote about this in his Spandau diary:

December 9, 1946. It would be wrong to imagine that the top men of the regime would have boasted of their crimes on the rare occasions when they met. At the trial we were compared to the heads of a Mafia. I recalled movies in which the bosses of legendary gangs sat around in evening dress chatting about murder and power, weaving intrigues, concocting coups. But this atmosphere of back room conspiracy was not at all the style of our leadership. In our personal dealings, nothing would ever be said about any sinister activities we might be up to. (1976, p.27)

Speer’s observation is corroborated by SS guard Theodor Malzmueller’s description of his introduction to mass murder upon his arrival at the Kulmhof (Chelmno) extermination camp:

When we arrived we had to report to the camp commandant, SS-Hauptsturmführer Bothmann. The SS-Hauptsturmführer addressed us in his living quarters, in the presence of SS-Untersturmführer Albert Plate. He explained that we had been dedicated to the Kulmhof extermination camp as guards and added that in this camp the plague boils of humanity, the Jews, were exterminated. We were to keep quiet about everything we saw or heard, otherwise we would have to reckon with our families’ imprisonment and the death penalty. (Klee, Dressen, and Riess 1991, p. 217)

The answer to the deniers’ overall contention that there was a conspiracy by Jews to concoct a Holocaust in order to finance the State of Israel (Rassinier 1978) is straightforward. The basic facts about the Holocaust were established before there was a State of Israel and before the United States or any other country gave it one cent. Moreover, when reparations were established, the amount Israel received from Germany was not based on numbers killed but on Israel’s cost of absorbing and resettling the Jews who fled Germany and German-controlled countries before the war and the survivors of the Holocaust who came to Israel after the war. In March 1951, Israel requested from the Four Powers reparations, to be calculated on this basis.

The government of Israel is not in a position to obtain and present a complete statement of all Jewish property taken or looted by the Germans, and said to total more than $6 thousand million. It can only compute its claim on the basis of total expenditures already made and the expenditure still needed for the integration of Jewish immigrants from Nazi-dominated countries. The number of these immigrants is estimated at some 500,000, which means a total expenditure of $1.5 thousand million. (Sagi 1980, p.55)

Needless to say, if reparations were based on the total number of survivors, then any Zionist conspirators should have exaggerated not the number of Jews killed by the Nazis but the number of survivors. In fact, given the provisions of the reparation settlement, if the deniers are right and only a few hundred thousand Jews died, then Germany owes Israel far more in reparations, for where else could those five to six million survivors have gone? Deniers might argue that the Zionist conspirators traded reparation money from Germany for a greater prize: money and long-term sympathy from all over the world. But here we really go off the deep end. Why should the supposed conspirators have risked sure money for some uncertain future payoff? In reality, the State of Israel as the recipient of German money is a myth. Most of it went to individual survivors, not to the Israeli government.

When all else fails, deniers shift from wrangling about intentionality, gassings and crematoria, and the number of Jews killed to arguing that the Nazi’s treatment of the Jews is really no different from what other nations do to their perceived enemies. Deniers point out, for example, that the U.S. government obliterated with atomic weapons two entire Japanese cities filled with civilians (Irving 1994) and forced Japanese-Americans into camps, which is just what the Germans did to their perceived internal enemy—the Jews (Cole 1994).

The response to this is twofold. First, just because another country does evil does not make your own evil right. Second, there is a difference between war and the systematic state-organized killing of unarmed people within your own country, not in self-defense, not to gain more territory, raw materials, or wealth, but simply because they are perceived as a type of Satanic force and inferior race. At his trial in Jerusalem, Adolf Eichmann, SS Obersturmbannführer of the RSHA and one of the chief implementers of the Final Solution, tried to make the moral equivalence argument. But the judge didn’t buy it, as this sequence from the trial transcript shows (Russell 1963, pp.278–279):

Judge Benjamin Halevi to Eichmann: You have often compared the extermination of the Jews with the bombing raids on German cities and you compared the murder of Jewish women and children with the death of German women in aerial bombardments. Surely it must be clear to you that there is a basic distinction between these two things. On the one hand the bombing is used as an instrument of forcing the enemy to surrender. Just as the Germans tried to force the British to surrender by their bombing. In that case it is a war objective to bring an armed enemy to his knees.

On the other hand, when you take unarmed Jewish men, women, and children from their homes, hand them over to the Gestapo, and then send them to Auschwitz for extermination it is an entirely different thing, is it not?

Eichmann: The difference is enormous. But at that time these crimes had been legalized by the state and the responsibility, therefore, belongs to those who issued the orders.

Halevi: But you must know surely that there are internationally recognized Laws and Customs of War whereby the civilian population is protected from actions which are not essential for the prosecution of the war itself.

Eichmann: Yes, I’m aware of that.

Halevi: Did you never feel a conflict of loyalties between your duty and your conscience?

Eichmann: I suppose one could call it an internal split. It was a personal dilemma when one swayed from one extreme to the other.

Halevi: One had to overlook and forget one’s conscience.

Eichmann: Yes, one could put it that way.

During his trial, Eichmann never denied the Holocaust. His argument was that “these crimes had been legalized by the state” and therefore the people that “issued the orders” are responsible. This was the classic defense used at the Nuremberg trials by most of the Nazis. Since the higher-ups all committed suicide—Hitler, Himmler, Göebbels, and Hermann Goring—they were off the hook, or so they thought.

We are not off the hook either. Like evolution denial, Holocaust denial is not simply going to go away and it is not benign or trivial. It has had and will have ugly and dire consequences, not only for Jews but for all of us and for future generations. We must provide answers to the claims of Holocaust deniers. We have the evidence and we must stand up and be heard.