Medieval and Modern Witch Crazes

In the small town of Mattoon, Illinois, a woman says that a stranger entered her bedroom late at night on Thursday, August 31, 1944, and anesthetized her legs with a spray gas. She reported the incident the next day, claiming she was temporarily paralyzed. The Saturday edition of the Mattoon Daily Journal-Gazette ran the headline “ANESTHETIC PROWLER ON LOOSE.” In the days to come, several other cases were reported. The newspaper covered these new incidents under the headline “MAD ANESTHETIST STRIKES AGAIN.” The perpetrator became known as the “Phantom Gasser of Mattoon.” Soon cases were occurring all over Mattoon, the state police were brought in, husbands stood guard with loaded guns, and many firsthand sightings were recounted. In the course of thirteen days, a total of twenty-five cases were reported. After a fortnight, however, no one was caught, no chemical clues were discovered, the police spoke of “wild imaginations,” and the newspapers began to characterize the story as a case of “mass hysteria” (see Johnson 1945; W. Smith 1994).

Where have we heard all this before? If this story sounds familiar, it might be because it has the same components as an alien abduction experience, only the paralysis is the work of a mad anesthetist rather than aliens. Strange things going bump in the night, interpreted in the context of the time and culture of the victims, whipped into a phenomenon through rumor and gossip—we are talking about modern versions of medieval witch crazes. Most people do not believe in witches anymore, and today no one is burned at the stake, yet the components of the early witch crazes are still alive in their many modern pseudoscientific descendants:

1. Victims tend to be women, the poor, the retarded, and others on the margins of society.

2. Sex or sexual abuse is typically involved.

3. Mere accusation of potential perpetrators makes them guilty.

4. Denial of guilt is regarded as farther proof of guilt.

5. Once a claim of victimization becomes well known in a community, other similar claims suddenly appear.

6. The movement hits a critical peak of accusation, when virtually everyone is a potential suspect and almost no one is above suspicion.

7. Then the pendulum swings the other way. As the innocent begin to fight back against their accusers through legal and other means, the accusers sometimes become the accused and skeptics begin to demonstrate the falsity of the accusations.

8. Finally, the movement fades, the public loses interest, and proponents, while never completely disappearing, are shifted to the margins of belief.

So it went for the medieval witch crazes. So it will likely go for modern witch crazes such as the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s and the “recovered memory movement” of the 1990s. Is it really possible that thousands of Satanic cults have secretly infiltrated our society and that their members are torturing, mutilating, and sexually abusing tens of thousands of children and animals? No. Is it really possible that millions of adult women were sexually abused as children but have repressed all memory of the abuse? No. Like the alien abduction phenomenon, these are products of the mind, not reality. They are social follies and mental fantasies, driven by a curious phenomenon called the feedback loop.

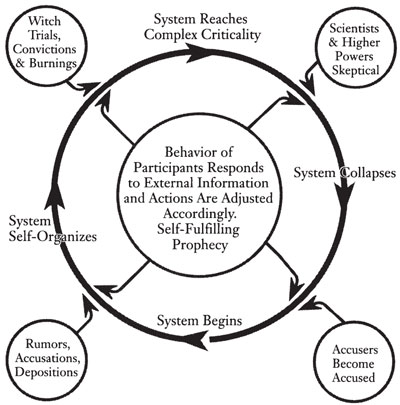

Why should there be such movements in the first place, and what makes these seemingly dissimilar movements play out in a similar manner? A helpful model comes from the emerging sciences of chaos and complexity theory. Many systems, including social systems like witch crazes, self-organize through feedback loops, in which outputs are connected to inputs, producing change in response to both (like a public-address system with feedback, or stock market booms and busts driven by flurries of buying and selling). The underlying mechanism driving a witch craze is the cycling of information through a closed system. Medieval witch crazes existed because the internal and external components of a feedback loop periodically occurred together, with deadly results. Internal components include the social control of one group of people by another, more powerful group, a prevalent feeling of loss of personal control and responsibility, and the need to place blame for misfortune elsewhere; external conditions include socioeconomic stresses, cultural and political crises, religious strife, and moral upheavals (see Macfarlane 1970; Trevor-Roper 1969). A conjuncture of such events and conditions can lead the system to self-organize, grow, reach a peak, and then collapse. A few claims of ritual abuse are fed into the system through word-of-mouth in the seventeenth century or the mass media in the twentieth. An individual is accused of being in league with the devil and denies the accusation. The denial serves as proof of guilt, as does silence or confession. Whether the defendant is being tried by the water test of the seventeenth century (if you float you are guilty, if you drown you are innocent) or in the court of public opinion today, accusation equals guilt (consider any well-publicized sexual abuse case). The feedback loop is now in place. The witch or Satanic ritual child abuser must name accomplices to the crime. The system grows in complexity as gossip or the media increase the amount and flow of information. Witch after witch is burned and abuser after abuser is jailed, until the system reaches criticality and finally collapses under changing social conditions and pressures (see figure 10). The “Phantom Gasser of Mattoon” is another classic example. The phenomenon self-organized, reached criticality, switched from a positive to a negative feedback loop, and collapsed—all in the span of two weeks.

FIGURE 10:

Witch craze feedback loop.

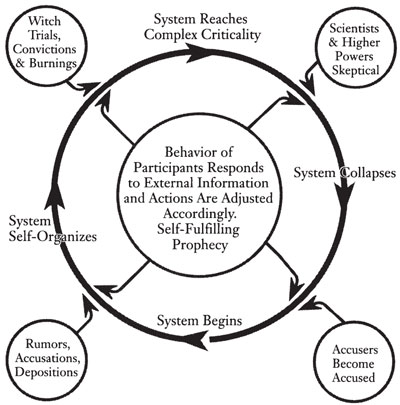

FIGURE 11:

Accusations of witchcraft at ecclesiastical courts, England, 1560–1620. [From Macfarlane 1970.]

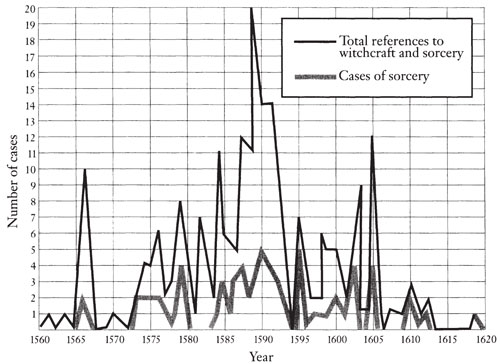

Data supporting this model exist. For example, note in figure 11 the rise and fall of accusations of witchcraft brought before the ecclesiastical courts in England from 1560 to 1620, and trace through the various parts of figure 12 the pattern of accusations in the witch craze that began in 1645 in Manningtree, England. The density of accusation drives the feedback loop to self-organize and reach criticality.

Over the past century dozens of historians, sociologists, anthropologists, and theologians proffered theories to explain the medieval witch craze phenomenon. We can dismiss up-front the theological explanation that witches really existed and the church was simply reacting to a real threat. Belief in witches existed for centuries prior to the medieval witch craze without the church embarking on mass persecutions. Secular explanations are as varied as the writer’s imagination would allow. Early in this historiography, Henry Lea (1888) speculated that the craze was caused by the active imaginations of theologians, coupled with the power of the ecclesiastical establishment. More recently, Marion Starkey (1963) and John Demos (1982) have offered psychoanalytic explanations. Alan Macfarlane (1970) used copious statistics to show that scapegoating was an important element of the craze, and Robin Briggs (1996) has recently reinforced this theory by showing how ordinary people used scapegoating as a means of resolving grievances. In one of the best books on the period, Keith Thomas (1971) argues that the craze was caused by the decline of magic and the rise of large-scale, formalized religion. H. C. E. Midelfort (1972) theorizes that it was caused by interpersonal conflict within and between various villages. Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English (1973) correlated it with the suppression of midwives. Linnda Carporael (1976) attributed the craze in Salem to suggestible adolescents high on hallucinatory substances. More likely are the accounts of Wolfgang Lederer (1969), Joseph Klaits (1985), and Ann Barston (1994), which examine the hypothesis that the witch craze was a combination of misogyny and gender politics. Theories and books continue to be produced at a steady rate. Hans Sebald believes that this episode of medieval mass persecution “cannot be explained within a monocausal frame; rather the explanation most likely consists of a multivariable syndrome, in which important psychological and societal conditions are inter-meshed” (1996, p. 817). I agree, but would add that these divers socio-cultural theories can be taken to a deeper theoretical level by grafting them into the witch craze feedback loop. Theological imaginations, ecclesiastical power, scapegoating, the decline of magic, the rise of formal religion, interpersonal conflict, misogyny, gender politics, and possibly even psychedelic drugs were all, to lesser or greater degrees, components of the feedback loop. They all either fed into or out of the system, driving it forward.

FIGURE 12:

Witch craze that originated in Manningtree, England, 1645. (top) Accusations by suspected witches against other suspected witches; (middle) accusations against suspected witches (central boxes) by other villagers; (bottom) spread of craze—arrows point from village of the accused witch to village of the supposed victim. Modeled by the feedback loop of figure 10, these data show how a craze begins, spreads, and reaches criticality. [From Macfarlane 1970.]

Hugh Trevor-Roper, in The European Witch-Craze, demonstrates how suspicions and accusations built upon one another as the scope and intensity of the feedback loop expanded. He provides this example from the county of Lorraine about the frequency of alleged witch meetings: “At first the interrogators … thought that they occurred only once a week, on Thursday; but, as always, the more evidence was pressed, the worse the conclusions that it yielded. Sabbats were found to take place on Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday, and soon Tuesday was found to be booked as a by-day. It was all very alarming and proved the need of ever greater vigilance by the spiritual police” (1969, p.94). It is remarkable how quickly the feedback loop self-organizes into a full-blown witch craze, and interesting to discover what happens to skeptics who challenge the system. Trevor-Roper was appalled by what he read in the historical documents:

To read these encyclopaedias of witchcraft is a horrible experience. Together they insist that every grotesque detail of demonology is true, that scepticism must be stifled, that sceptics and lawyers who defend witches are themselves witches, that all witches, “good” or “bad,” must be burnt, that no excuse, no extenuation is allowable, that mere denunciation by one witch is sufficient evidence to burn another. All agree that witches are multiplying incredibly in Christendom, and that the reason for their increase is the indecent leniency of judges, the indecent immunity of Satan’s accomplices, the sceptics, (p.151)

What is especially curious about the medieval witch craze is that it occurred at the very time experimental science was gaining ground and popularity. This is curious because we often think that science displaces superstition and so one would expect belief in things like witches, demons, and spirits to have decreased as science grew. Not so. As modern examples show, believers in paranormal and other pseudoscientific phenomena try to wrap themselves in the mantle of science because science is a dominating force in our society but they still believe what they believe. Historically, as science grew in importance, the viability of all belief systems began to be directly attached to experimental evidence in favor of specific claims. Thus, scientists of the day found themselves investigating haunted houses and testing accused witches by using methods considered rigorous and scientific. Empirical data for the existence of witches would support belief in Satan which, in turn, would buttress belief in God. But the alliance between religion and science was uneasy. Atheism as a viable philosophical position was growing in popularity, and church authorities put themselves in a double-bind by looking to scientists and intellectuals to respond. As one observer at a seventeenth-century witch trial of an Englishman named Mr. Darrell noted, “Atheists abound in these days and witchcraft is called into question. If neither possession nor witchcraft [exists], why should we think that there are devils? If no devils, no God” (in Walker 1981, p.71).

The best modern example of a witch craze would have to be the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s. Thousands of Satanic cults were believed to be operating in secrecy throughout America, sacrificing and mutilating animals, sexually abusing children, and practicing Satanic rituals. In The Satanism Scare, James Richardson, Joel Best, and David Bromley argue persuasively that public discourse about sexual abuse, Satanism, serial murders, or child pornography is a barometer of larger social fears and anxieties. The Satanic panic was an instance of moral panic, where “a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions; ways of coping are evolved or resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates” (1991, p.23). Such events are used as weapons “for various political groups in their campaigns” when someone stands to gain and someone stands to lose by the focus on such events and their outcome. According to these authors, the evidence for widespread Satanic cults, witches’ covens, and ritualistic child abuse and animal killings is virtually nonexistent. Sure, there is a handful of colorful figures who are interviewed on talk shows or dress in black and burn incense or introduce late-night movies in a pushup bra, but these are hardly the brutal criminals supposedly disrupting society and corrupting the morals of humanity. Who says they are?

The key is in the answer to the question, “Who needs Satanic cults?” “Talk-show hosts, book publishers, anti-cult groups, fundamentalists, and certain religious groups” is the reply. All thrive from such claims. “Long a staple topic for religious broadcasters and ‘trash TV’ talk shows,” the authors note, “satanism has crept into network news programs and prime-time programming, with news stories, documentaries, and made-for-TV movies about satanic cults. Growing numbers of police officers, child protection workers, and other public officials attend workshops supported by tax dollars to receive formal training in combating the satanist menace” (p.3). Here is the information exchange fueling the feedback loop and driving the witch craze toward higher levels of complexity.

The motive, like the movement, is repeated historically from century to century as a shunt for personal responsibility—fob off your problems on the nearest enemy, the more evil the better. And who fits the bill better than Satan himself, along with his female co-conspirator, the witch? As sociologist Kai Erikson observed, “Perhaps no other form of crime in history has been a better index to social disruption and change, for outbreaks of witchcraft mania have generally taken place in societies which are experiencing a shift of religious focus—societies, we would say, confronting a relocation of boundaries” (1966, p.153) Indeed, of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century witch crazes, anthropologist Marvin Harris noted, “The principal result of the witch-hunt system was that the poor came to believe that they were being victimized by witches and devils instead of princes and popes. Did your roof leak, your cow abort, your oats wither, your wine go sour, your head ache, your baby die? It was the work of the witches. Preoccupied with the fantastic activities of these demons, the distraught, alienated, pauperized masses blamed the rampant Devil instead of the corrupt clergy and the rapacious nobility” (1974, p.205).

Jeffrey Victor’s book, Satanic Panic: The Creation of a Contemporary Legend (1993), is the best analysis to date on the subject, and the subtitle summarizes his thesis about the phenomenon. Victor traces the development of the Satanic cult legend by comparing it to other rumor-driven panics and mass hysterias and showing how individuals get caught up in such phenomena. Participation involves a variety of psychological factors and social forces, combined with information input from modern as well as historical sources. In the 1970s, there were rumors about dangerous religious cults, cattle mutilations, and Satanic cult ritual animal sacrifices; in the 1980s, we were bombarded by books, articles, and television programs about multiple personality disorder, Procter & Gamble’s “Satanic” logo, ritual child abuse, the McMartin Preschool case, and devil worship; and the 1990s have given us the ritual child abuse scare in England, reports that the Mormon Church was infiltrated by secret Satanists who sexually abuse children in rituals, and the Satanic ritual abuse scare in San Diego (see Victor 1993, pp. 24–25). These cases, and many others, drove the feedback loop forward. But now it is reversing. In 1994, for example, Britain’s Ministry of Health conducted a study that found no independent corroboration for eyewitness claims of Satanic abuse of children in Britain. According to Jean La Fontaine, a professor from the London School of Economics, “The alleged disclosures of satanic abuse by younger children were influenced by adults. A small minority involved children pressured or coached by their mothers.” What was the driving force? Evangelical Christians, suggests La Fontaine: “The evangelical Christian campaign against new religious movements has been a powerful influence encouraging the identification of satanic abuse” (in Shermer 1994, p.21).

A frightening parallel to the medieval witch crazes is what has come to be known as the “recovered memory movement.” Recovered memories are alleged memories of childhood sexual abuse repressed by the victims but recalled decades later through use of special therapeutic techniques, including suggestive questioning, hypnosis, hypnotic age-regression, visualization, sodium amytal (“truth serum”) injections, and dream interpretation. What makes this movement a feedback loop is the accelerating rate of information exchange. The therapist usually has the client read books about recovered memories, watch videotapes of talk shows on recovered memories, and participate in group counseling with other women with recovered memories. Absent at the beginning of therapy, memories of childhood sexual abuse are soon created through weeks and months of applying the special therapeutic techniques. Then names are named—father, mother, grandfather, uncle, brother, friends of father, and so on. Next is confrontation with the accused, who inevitably denies the charges, and termination of all relations with the accused. Shattered families are the result (see Hochman 1993).

Experts on both sides of this issue estimate that at least one million people have “recovered” memories of sexual abuse since 1988 alone, and this does not count those who really were sexually abused and never forgot it (Crews et al. 1995; Loftus and Ketcham 1994; Pendergrast 1995). Writer Richard Webster, in his fascinating Why Freud Was Wrong (1995), traces the movement to a group of psychotherapists in the Boston area who in the 1980s, after reading psychiatrist Judith Herman’s 1981 book, Father-Daughter Incest, formed therapy groups for incest survivors. Since sexual abuse is a real and tragic phenomenon, this was an important step in bringing it to the attention of society. Unfortunately, the idea that the subconscious is the keeper of repressed memories was also proffered, based on Herman’s description of one woman whose “previously repressed memories” of sexual abuse were reconstructed in therapy. In the beginning, membership mostly consisted of those who had always remembered their abuse. But gradually, Webster notes, the process of therapeutic memory reconstruction entered the sessions.

In their pursuit of the hidden memories which supposedly accounted for the symptoms of these women, therapists sometimes used a form of time-limited group therapy. At the beginning of the ten or twelve weekly sessions, patients would be encouraged to set themselves goals. For many patients without memories of incest the goal was to recover such memories. Some of them actually defined their goal by saying “I just want to be in the group and feel I belong.” After the fifth session the therapist would remind the group that they had reached the middle of their therapy, with the clear implication that time was running out. As pressure was increased in this way women with no memories would often begin to see images of sexual abuse involving father or other adults, and these images would then be construed as memories or “flashbacks.” (1995, p.519)

The feedback loop for the movement now began to self-organize, encouraged by psychotherapist Jeffrey Masson’s 1984 book, The Assault on Truth, in which he rejected Freud’s claim that childhood sexual abuse was fantasy and argued that Freud’s initial position—that the sexual abuse so often recounted by his patients was actual, rampant, and responsible for adult women’s neuroses—was the correct one. The movement became a full-blown witch craze when Ellen Bass and Laura Davis published The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse in 1988. One of its conclusions was “If you think you were abused and your life shows the symptoms, then you were” (p.22). The book sold more than 750,000 copies and triggered a recovered memory industry that involved dozens of similar books, talk-show programs, and magazine and newspaper stories.

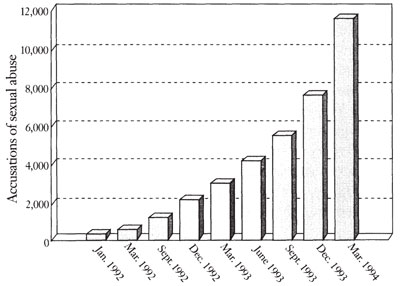

The controversy over recovered versus false memories still rages among psychologists, psychiatrists, lawyers, the media, and the general public. Because childhood sexual abuse does happen, and probably more frequently than any of us like to think, much is at stake when accusations made by the alleged victims themselves are discounted. But what we appear to be experiencing with the recovered memory movement is not an epidemic of childhood sexual abuse but an epidemic of accusations (see figure 13). It’s a witch craze, not a sex craze. The supposed numbers alone should make us skeptical. Bass and Davis and others estimate that as many as one-third to one-half of all women were sexually abused as children. Using the conservative percentage, this means that in America alone 42.9 million women were sexually abused. Since they have to be abused by someone, this means about 42.9 million men are sex offenders, bringing us to a total of 85.8 million Americans. Additionally, many of these cases allegedly involve mothers who consent and friends and relatives who participate. This would push the figure to over 100 million Americans (about 38 percent of the entire population) involved in sexual abuse. Impossible. Impossible even if we cut that estimate in half. Something else is going on here.

FIGURE 13:

Registered accusations of sexual abuse against parents, March 1992–March 1994. [Courtesy False Memory Syndrome Foundation.]

This movement is made all the scarier by the fact that not only can anyone be accused, the consequences are extreme—incarceration. Many men and a number of women have been sent to jail, and some are still sitting there, after being convicted of sexual abuse on nothing more than a recovered memory. Given what is at stake, we must proceed with extreme caution. Fortunately, the tide seems to be turning in favor of the recovered memory movement being relegated to a bad chapter in the history of psychiatry. In 1994 Gary Ramona, father of his accuser, Holly Ramona, won his suit against her two therapists, Marche Isabella and Dr. Richard Rose, who had helped Holly “remember” such events as her father forcing her to perform oral sex on the family dog. The jury awarded Gary Ramona $500,000 of the $8 million he sought mainly because he had lost his $400,000-a-year job at the Robert Mondavi winery as a result of the fiasco.

Not only are the accused taking action but accusers are suing their therapists for planting false memories. And they are winning. Laura Pasley (1993), who once believed she was a victim of sexual abuse during her childhood, has since recanted her recovered memory, sued and won a settlement from her therapist, and her story has made the rounds in the mass media. Many other women are now reversing their original claims and filing lawsuits against their therapists. These women have become known as “retractors,” and there is now even a therapist retractor (Pendergrast 1996). Lawyers are helping to reverse the feedback loop by holding therapists accountable through the legal system. The positive feedback loop is now becoming a negative one, and thanks to people like Pasley and organizations like the False Memory Syndrome Foundation, the direction of information exchange is reversing.

The reversal of the feedback loop was given another boost in October 1995, when a six-member jury in Ramsey County, Minnesota, awarded $2.7 million to Vynnette Hamanne and her husband after a six-week trial about charges that Hamanne’s St. Paul psychiatrist, Dr. Diane Bay Humenansky, planted false memories of childhood sexual abuse. Hamanne went to Humenansky in 1988 with general anxiety and no memories whatsoever of childhood sexual abuse. After a year of therapy with Humenansky, however, Hamanne was diagnosed with multiple personality disorder—Humenansky “discovered” no less than 100 different personalities. What had caused Hamanne to become so many different people? According to Humenansky, Hamanne was sexually abused by her mother, father, grandmother, uncles, neighbors, and many others. Because of the trauma, Hamanne allegedly repressed the memories. Through therapy, Humenansky reconstructed a past for Hamanne that even included Satanic ritual abuse featuring dead babies being served as meals “buffet style.” The jury didn’t buy it. Neither did another jury, which on January 24, 1996, awarded another one of Humenansky’s clients, E. Carlson, $2.5 million (Grinfeld 1995, p.1).

Finally, one of the most famous cases involving repressed memories was recently dismissed and the accused released from jail. In 1989 George Franklin’s daughter, Eileen Franklin-Lipsker, told police that her father had killed her childhood friend Susan Nason in 1969. Her evidence? A twenty-year-old recovered memory upon which (and without farther evidence) Franklin was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison in January 1991. Franklin-Lipsker claimed that the memory of the murder returned to her while she was playing with her own daughter, who was close to the age of her murdered childhood friend. But in April 1995, U.S. District Court Judge Lowell Jensen ruled that Franklin had not received a fair trial because the original judge refused to let the defense introduce newspaper articles about the murder that could have provided Franklin-Lipsker with the details of the crime. In other words, her memory may have been constructed, not recovered. Additionally, Franklin-Lipsker’s sister, Janice Franklin, in sworn testimony revealed that she and her sister had been hypnotized before their father’s trial to “enhance” their memories. The final straw was when Franklin-Lipsker told investigators that she remembered her father committing two more murders but investigators were unable to link Franklin to either of them. One of the memories was so general that they could not even find an actual murder to go with it. In the other, Franklin allegedly raped and murdered an eighteen-year-old girl in 1976, but investigators placed Franklin at a union meeting at the time of the murder, and DNA and semen tests confirmed Franklin’s innocence. Franklin’s wife, Leah, who testified against him in the 1990 trial, has now recanted and says she no longer believes in the concept of repressed memories. Franklin’s attorney concluded, “George has been in prison or jail for six years, seven months, and four days. It is an absolute travesty and a tragedy. This has been a Kafkaesque experience for him” (Curtius 1996). Indeed, the entire recovered memory movement is a Kafkaesque experience.

The parallels with Trevor-Roper’s description of how a medieval witch craze worked can be eerie. Consider the case of East Wenatchee, Washington, in 1995. Detective Robert Perez, a sex-crimes investigator who took as his mission the rescue of the children of his city from what he believed was an epidemic of sexual abuse. Perez accused, charged, convicted, and terrorized citizens of this rural community with literally unbelievable claims. One woman was charged with over 3,200 acts of sexual abuse. One elderly gentleman was charged with having sexual intercourse twelve times in one day, which he admitted was impossible even when he was a teenager. And who were the accused? As in the medieval witch crazes, they were mainly poor men and women unable to hire adequate legal counsel. And who was doing the accusing? Young girls with active imaginations who had spent a lot of time with Detective Perez. And who was Perez? According to a police department evaluation, Perez had a history of petty crime and domestic strife, and it described him as “pompous,” with an “arrogant approach.” The report also stated that Perez appeared “to pick out people and target them.” Soon after he was hired, Perez began interrogating vulnerable, dysfunctional girls without their parents being present. Not surprising, he did not tape the interviews; instead, he wrote out statements of accusation for the girls, who then signed them, usually after hours of relentless questioning (Carlson 1995, pp.89-90).

While no one was burned in East Wenatchee, these young girls (the most prolific accuser was ten years old), because of Perez’s influence and powers as a police officer, put more than twenty adults in jail. Over half of the incarcerated were poor women. Interestingly, anyone who hired a private attorney was not imprisoned. The message was clear—fight back. In the case of the ten-year-old accuser, Perez pulled her out of school, questioned her for four hours, then threatened to arrest her mom unless she admitted to being the victim of sex orgies that included her mom. “You have ten minutes to tell the truth,” Perez insisted, promising that he would let her go home if she did. The girl signed the paper and Perez promptly arrested and jailed the mother. The girl did not see her mother again for six months. When the mother finally hired a lawyer, all 168 charges were dropped. East Wenatchee was firmly locked in a witch craze feedback loop that reached criticality when this epidemic of accusation was reported in the mass media (including a one-hour special on ABC and a Time magazine article). Now that Perez has been exposed, the accused are turning on him, the girls are retracting their accusations, lawsuits are being filed by the victims and their destroyed families, and the feedback loop has reversed itself.

The troubling aspect of this particular craze and of the sexual abuse hysteria sweeping across America over the last few years is that some genuine sex offenders may well go free in the inevitable backlash against the panic. Childhood sexual abuse is real. Now that it has been turned into a witch craze, it may be some time before society finds its balance in dealing with it.