The battle for Crete was a German victory but a costly one. Out of an assault force of just over 22,000 men, the Germans suffered almost 6,500 casualties, of which 3,352 were killed or missing in action. Almost a third of the Ju-52s used in the operation were damaged or destroyed. The British and Commonwealth forces suffered almost 3,500 casualties (of which just over 1,700 were killed) and almost 12,000 were taken prisoner (including Lieutenant Colonel Walker’s 2/7 Australian Battalion), while the Greeks had approximately 10,000 men taken prisoner. The Royal Navy lost three cruisers and six destroyers sunk, and one aircraft carrier, two battleships, six cruisers and seven destroyers were badly damaged, with the loss of over 2,000 men. The RAF lost some 47 aircraft in the battle. Exactly how many Greek soldiers and Cretan civilians died during the fighting will never be known.

There were positive lessons to be learned from the battle, such as the importance of air power in providing support to the ground troops and its impact on naval operations. Superior German leadership and initiative also contributed to the outcome. However, it is the failings by both sides that deserve most attention. The use of intelligence and the performance of command and control structures were the key to the evolution of the battle for both the Germans and Allies.

The German airborne forces were relatively well equipped but their operational planning was flawed due to poor intelligence. The lack of surprise resulted in high casualties and brought the operation perilously close to failure. Had it not been for the support of Von Richthofen’s Fliegerkorps VIII and the leadership and initiative qualities shown by the German officers, particularly the junior commanders, the battle would have been lost.

The numerically superior but poorly equipped Allied garrison lost the battle by only a slim margin, due to the fact that the key commanders involved failed to understand both the threat from and the vulnerabilities of an airborne force. They also missed the opportunity to launch an aggressive counterattack. Throughout the battle, the Luftwaffe utilised its immense advantage in combat power to help restrict the impact made by the Royal Navy, support the beleaguered paratroopers, demoralise the defenders and interdict Allied troop movements. The casualty figures show a higher than usual killed-to-wounded ratio, a testament to the ferocity of the battle and how close the result was.

As a result of the huge losses suffered by the Fallschirmjäger in Crete, it was forbidden to mount any large-scale operations in the future, with Hitler telling Student on 19 July 1941 that the day of the paratrooper was over. Apart from a few small-scale operations, the paratroopers mainly served as elite infantry for the rest of the war. Crete was rightly dubbed the ‘Graveyard of the Fallschirmjäger’ with Student in 1952 admitting that ‘For me, the Battle of Crete … carries bitter memories.’

Allied troops from the 4th New Zealand Brigade disembark in Alexandria, Egypt after being evacuated from Crete by the destroyer HMS Nizam, 31 May 1941. It is obvious that as many men as possible had been put on the ship, which was dangerous under the circumstances as all Allied ships were subject to air attack on their return journey to Egypt. (Alexander Turnbull Library, DA-00399)

The Gebirgsjäger who were drafted into the operation at the last moment performed admirably, as they did throughout the war. The fact that the operation was undertaken just three weeks after the fall of Greece is a testament to the flexibility, ingenuity and determination of the German armed forces who had to overcome immense logistical difficulties.

British operations on Crete were hampered by the poor shape many units found themselves in after the campaign in Greece. Indecision, misunderstanding, a lack of information (at least when the fighting started) and poor communications in the chain of command, both on Crete itself and from Crete to Egypt, also played a part. The order to Freyberg to preserve the airfields for the future use of the RAF also proved misguided. The importance and reliability of the ‘Ultra’ intercepts was not apparent to Freyberg as the exact source of the information was not revealed to him. As such he continued to focus primarily on the threat of an amphibious attack. There was no clear-cut plan of defence, and what was undertaken was done so at the last minute. The defence of the island was improvised and with the British at full stretch in the rest of North Africa and the Middle East, the men and matériel necessary for the defence of Crete could not be spared.

None of the senior commanders performed with distinction. The exception was Cunningham who appreciated the impact of air power on naval operations, the strategic consequences for the Allies of a British defeat at Crete, and the possibility of a shift in the naval balance of power in the Mediterranean. Generally, Allied commanders showed too little aggression and their appreciation of the situation always lagged behind events – something that did not hinder the Germans in the same way, as their commanders led from the front. There was also considerable political interference with Wavell’s command from London, specifically from the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

In the wake of the final Allied evacuation of Crete on 1 June, and the subsequent surrender of the remaining Allied forces, the occupied island was divided into two zones. The main German zone covered the western provinces of Hania, Rethymnon and Heraklion, while the subsidiary Italian zone covered the provinces of Sitia and Lasithi in the east. The Italian occupation force consisted of the Siena Division, whose commander, Generale Angelo Carta, had his headquarters in Neapolis and ran his zone with a somewhat more liberal and relaxed attitude than many of his German counterparts. The German Garrison HQ was in Hania and its first commandant, General Waldemar Andrae, took over from Student and was in turn succeeded in 1942 by another paratrooper, Bruno Bräuer, former commander of the 1st Fallschirmjäger Regiment. In the spring of 1944, the hated Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller took control, and was to prove the most brutal of the garrison commanders, a reputation firmly established while in command of the 22nd Luftlande Division at Arhanes, south of Heraklion. The elite 22nd Luftlande Division had been sent to Crete in the summer of 1942 much to the annoyance of a number of senior German officers, who considered it a waste to use such a highly trained division in a garrison role. The garrison strength fluctuated wildly, depending on how the North African and Russian campaigns were progressing and the perception of the threat of invasion. It reached its zenith in 1943 with 75,000 and gradually declined to its lowest of 10,000 just before its surrender on 12 May 1945.

Sergeant Tom Moir (second from left) with an RAF corporal on his right and two civilians on Crete, May 1943. Moir had escaped from the island and been sent back to help organise the remaining Allied troops who were in hiding for evacuation. The RAF corporal was eventually captured by German troops in Mhoni while trying to reach New Zealand soldiers assembling for evacuation and he was sent to a prisoner of war camp in Germany. (Alexander Turnbull Library, DA-12587)

Undoubtedly, the hostile reaction of the Cretan population came as a shock to the Germans as they had expected a more welcoming attitude, the fiercely independent Cretans always having viewed the established Greek government with suspicion and distaste. To the Cretans, however, the Germans were just another invader whom they would fight to defend their homes, island and freedom. Beginning in the summer of 1941, they started to form centres of resistance. The initial aim was to gather as many of the British and Commonwealth troops remaining on the island as possible. The Cretan guerrillas took it upon themselves to protect, feed and clothe these Allied servicemen and, where possible, arrange their safe evacuation so they could carry on the fight elsewhere. For this they needed links with the main headquarters in Cairo and other parts of the Middle East. Over time an effective communications network was established to facilitate not only the evacuation of Allied servicemen, but also the introduction of members of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), to help organise and train the guerrillas, and deliveries of equipment and supplies. For the next four years the Cretan resistance harried the occupying German forces, tying down large numbers of enemy troops that could have been employed elsewhere. The Cretans suffered harsh reprisals as a result, including mass executions and the burning of villages.

This resistance and the help provided by the SOE meant that Crete became the stage for the exploits of a number of extraordinary British servicemen such as Patrick Leigh-Fermor, Dennis Ciclitira, Billy Moss and Xan Fielding. Perhaps the most famous episode was that immortalised on screen in the film Ill Met By Moonlight, starring Dirk Bogarde as Leigh-Fermor. The incident was the capture of General Heinrich Kreipe, commander of the 22nd Luftlande Division by Major Patrick Leigh-Fermor and Captain Stanley Moss with two Greek SOE agents on 26 April 1944. Their original target had been Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, but as a result of delays in the group’s rendezvousing on Crete, Kreipe had replaced Müller. It was decided that the attempt should continue as planned nevertheless. The site for the ambush was a T-junction where the Arhanes road met the Houdesti–Heraklion road, with high banks and ditches on each side. The British officers were disguised as German traffic policemen and could speak German very well. Waving red lamps and traffic signs they flagged the car down and told the driver that the road was unsafe further on. The general was quickly captured and taken prisoner, and when he began to shout was told that he was a prisoner of British commandos and had better shut up. Some of the party then got into the car and drove on with the general until they reached the point where they had to cross the mountains on foot. The commandos left a note in the car that read:

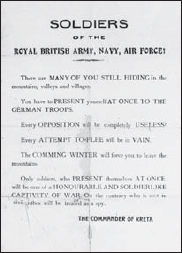

A poster displayed in Crete after the German occupation to try and encourage Allied servicemen to surrender. Many Allied servicemen had gone into hiding rather than surrendering and were cared for by the local population, despite threats of severe punishment. A large number managed to make their way back to Egypt, for example, over 300 were evacuated by submarine alone. (Alexander Turnbull Library, DA-10726)

TO THE GERMAN AUTHORITIES IN CRETE

Gentlemen, Your Divisional Commander, General KREIPE, was captured a short time ago by a BRITISH raiding force under our command. By the time you read this, he will be on his way to Cairo. We would like to point out most emphatically that this operation was carried out without the help of CRETANS or CRETAN partisans and that the only guides used were serving soldiers of HIS HELLENIC MAJESTY’s FORCES in the Middle East, who came with us. Your General is an honourable prisoner of war and will be treated with all the consideration owing to his rank. Any reprisals against the local population will be wholly unwarranted and unjust.

Auf baldiges Wiedersehen!

P.S. We are very sorry to have to leave this beautiful car behind.

The Germans initially thought that he had been taken by guerrillas and, in a quickly printed leaflet, threatened to raze every village in the Heraklion area to the ground and take severe reprisals against the local population. Patrols and reconnaissance aircraft combed the hills leading south (the most obvious escape route) and in fact occupied the beach that had been selected for the evacuation. Fortunately the commandos heard about this and remained hidden while a new evacuation point was selected. It took the party 17 days to reach the new beach, during which the general fell and his arm had to be put in a sling. The group reached the rendezvous successfully and were taken off safely, reaching Mersa Matruh on the North African coast after a stormy crossing.