Learning to Run

Iwalked onto the ward, my shoes squeaking on the newly buffed floor, my scrubs starched and pressed and my hands shaking a bit from what I was about to do. I’m not real sure but it’s also quite possible my knees were knocking, because after all, it was my first day as a newly trained poly-trauma nurse, and I was about to meet the first Marine I would be assigned. He had been injured during the brutal fighting in Fallujah, Iraq.

As I was standing just to the side of the entrance to his room, about to knock on his door, my thoughts went back to how my journey to this point had started. It was February 2001 and I was at a cabin north of Hibbing, Minnesota, surrounded by friends, and as we sat at the breakfast table the last morning of the weekend someone said to everyone: “Hey are you doing now what you dreamed of as a kid?” The question went around the table until it was my turn.

I sat there for a long moment, thinking, “It never occurred to me to ask this question of myself or answer it.” I looked up from my plate of pancakes and admitted, “I always dreamed of being a nurse and specifically an Army nurse.”

Months went by and that weekend slipped into a distant memory; however the words I had spoken kept swirling back until one afternoon I decided to do something about it. I contacted a nursing school, the first one that advertised “weekend college for working adults,” and filled out the admission form. I had not, at this point, truly entertained the idea. I filled out the form assuming I might get a no and then I could remove the thought from ever popping up again and carry on. I received a form letter in the mail explaining there was a waiting list and it might be a year or two until they would have an opening.

Ready to put the idea of becoming a nurse behind me, I did not give it another thought until months later when my phone rang and I was advised there was an unexpected opening and I had been admitted for the fall semester.

I am a believer in God and I pray, and throughout this whole process I had prayed and believed that if this was the path I was supposed to take then a way would be made where there seemed to be none. My first day of nursing school was Tuesday, September 11, 2001.

Knocking on the door of the Marine’s room, I heard him before I laid eyes on him, and the tone and pitch of his voice reminded me of the sound of a kid who had just been through something unimaginable and was in need of reassurance and protection. I had a vague thought of the challenges that lay ahead.

As I entered the room, I saw a young man full of bandages and tubes, and most notably there was a large bandage wrapped around his head. My nose picked up a strange sickly smell I could not identify. I introduced myself and he looked right through me, a look I would later become very familiar with. He acknowledged me with indifference and so began my first day.

As I have had the opportunity to reflect back on that first day and what followed, it’s a wonder I made it through the first week. I had such high expectations of myself as a nurse, of the others on the nursing staff, and of this Marine. It is a good thing I did not know any different. I had every expectation that he would fully recover, be able to lead a life that, while different from what he might have planned, would still be rewarding and valuable. So that is how I approached my care planning for him. I would be tough on him, and he was definitely going to be tough on me and every other nurse who would provide care for him throughout his year-and-a-half-long course of recovery.

My dream of being an Army nurse did not pan out; however my desire to care for wounded servicemen and women did. In August of 2005 I was encouraged to attend a job fair the Minneapolis VA was having. My mother had heard about it and thought it would be a great opportunity for me. I argued with her that nothing ever came out of job fairs. In all my wisdom and knowledge, I flatly refused to go, justifying to myself that it would be a big waste of time. Still, a small voice nudged me and before I knew it my car was heading south toward the VA in downtown Minneapolis. I arrived at two o’clock and by three I had been given a conditional offer of employment to start the next month, September 2005, as one of the first poly-trauma registered nurses to be hired outside of the VA system.

An IED exploded as his vehicle was driving past it. A chunk of metal and the debris sliced through his helmet. MARINE CORPS PHOTO

The first three months of this Marine’s recovery were tough. At just twenty-one years old he had witnessed his best friend dying during his first tour in Iraq, made it unscathed through his second tour, and was injured by an IED hidden in a Dumpster on his third deployment.

It detonated while his vehicle was driving past it. He had massive injuries to his brain. The IED delivered more than just the blast: A chunk of the Dumpster and whatever filth had been in the Dumpster prior to the blast had sliced through his helmet, effectively taking off a part of his skull and his brain. His head wound was contaminated and required wound cleaning and debriding daily. He also had a traumatic brain injury that impaired his ability to control his emotions, actions, and outbursts, he had short-term memory issues, and the blast had also left him paralyzed on one side. He was prone to fits of anger and acting out on this anger.

Many people talked about him as already being over with, and I heard things like “Well, if he ever makes it out of here he will either be in jail or dead soon after he is discharged.” His behaviors were extreme and this Marine had injured members of the staff by throwing items, breaking things off the wall, and busting a sink off its moorings. But I refused to give up on him: not because I had not questioned in my own mind all of the things others were saying about him but because he was a representative of the freedoms I enjoyed every day. He volunteered, he effectively went in my place, and he took that blast for me and every other American. But while others only saw a damaged Marine, what I witnessed on a daily basis was a Marine who refused to give up.

There are many stories about heroics on the battlefield but very few about the battles and fortitude of the wounded during their recovery. I have been given the greatest honor and that is to “care for him who has borne the burden,” and entrusted with a precious vocation to use my skills, knowledge, and abilities as a nurse to bring healing and to protect life, and also to be an advocate and to fight for those under my care.

“. . . others only saw a damaged Marine . . . I witnessed on a daily basis a Marine . . . who refused to give up.” Though in constant pain, he endured hell to get his life back to some semblance of normalcy. AIR FORCE PHOTO

This Marine was in constant pain every day; it was difficult for him to relearn how to walk, how to eat, how to put his socks on, how to shower, and all the things we take for granted on a daily basis. I saw beads of sweat on his brow as he struggled to stand on his own for the first time post-injury, but not once in that year and a half did this Marine ever give up. Not once. Ever. He fought through the pain, the frustration, the anger, the setbacks, and waking up every day realizing he was lying wounded in a bed at the VA and his life would never be the same.

In some ways his journey and mine were connected, intertwined. His path was not one of his choice, but a path he had agreed to when he raised his hand and took his oath as a Marine. My path was one of my choosing and one that began years before when I dreamed about being an Army nurse, but didn’t become reality until I was called up.

I believe in a life led in response to being called. Everything up to that point in my recent past had led me to be a nurse for this particular Marine. My service in the Army Reserves and National Guard prepared me to understand the military culture, to be able to have something in common with him—not that I would fully understand or know his specific journey, for that belongs to him alone. But it did provide me with the skills necessary to make a connection with this Marine, resulting in a therapeutic relationship that would help promote all the work being done by the various therapists, the doctors, and everyone involved in his care. This Marine had survived against all the odds; his medic had to convince a trauma team to work on him as his injuries were so catastrophic he was not expected to live.

At the same time, I was learning to stand on my own two feet as a nurse, going through the fire, making mistakes and adjusting to the new environment I had been placed in. This Marine was too. The difference being I was there for him; I was one nurse along the path who was willing to be utilized so this Marine could heal and be successful in whatever he would choose to do. He had been chosen to live.

If I had not been a believer in God prior to working with this Marine, I definitely would have been after. Too many things came together in his story for there to be any other explanation than that he was being called for some unknown purpose, post-injury. My proudest moment a poly-trauma nurse, up to that point, was observing this Marine on his discharge day, after being told for months he would be lucky just to walk again, let alone ever run out the front door of the VA. But in fact, he was walking, talking, running, and he was able to make decisions for himself. The last I had heard, he was working at a part-time job and was writing a book about his injuries, his struggles, and his accomplishments. Semper Fi Marine!

—Connie Bengston, BSN, RN, PHN

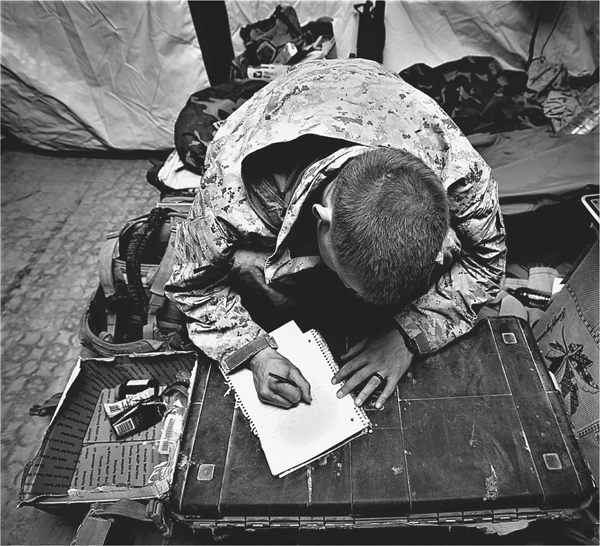

It might take him a little longer than anyone else, but writing a book about his experiences gives this Marine purpose . . . a mission, a reason to get out of bed . . . a reason to keep on living. MARINE CORPS PHOTO

A sniper’s bullet has a nasty sting. If it travels straight and true, it can enter the human body small and exit much larger. But if it hits bone along the way, it can ricochet through the body, ripping into vital organs, hitting bone again, meandering at high velocity with devastating effectiveness. As an Army ICU nurse in Iraq, Maj. Virginia Vardon-Smith witnessed all too often the damage done by snipers’ bullets.