A Father Shows His Appreciation

During the summer of 2006 I worked at Ibn Sina Hospital in Iraq, deployed there with the 10th Combat Support Hospital out of Fort Carson, Colorado. I was a critical care nurse working in the ICU in the hospital located in the Green Zone in Baghdad. We were very busy with incoming casualties due to the heavy action taking place in Sadr City. This particular morning, we had been given a report that a seriously wounded soldier was coming in with a significant vascular injury to his left shoulder area.

Our role, with any of our seriously injured soldiers coming in, is to do emergency surgery, and stabilize them for their quick transition out of Iraq and on their way to the American hospital in Landstuhl, Germany. As the charge nurse that morning, I was assigned to this patient. I did my normal checks for things needed at the bedside, filled out paperwork, and checked out our new cellphone soldiers could use to touch base with their families once they were awake and alert enough to talk. Our phone wasn’t working so I called down to the Patient Administration section and asked to borrow their phone. I remember this very clearly as I had to argue with a major and actually had to put her in At Ease! As unpleasant as it was, my patient would be coming out of surgery within a half-hour, I didn’t have time to argue, and I needed a phone that worked! And I needed it now. I later had to apologize, but that was after my patient had been flown out.

I received an update from Anesthesia at the bedside that a high-caliber round literally tore all the major vessels in his left shoulder (the brachial plexus) and he had had a very significant vascular repair including his aorta. He was lucky his medic on the scene told him, “Don’t let anyone take this dressing out of this wound or you will die!” He followed the medic’s instructions to the point where he argued with the Emergency Department doctors when they were trying to evaluate his wounds when he arrived.

The injured soldier was in the turret of his Humvee when he was hit in the shoulder and the bullet entered the gap in his body armor, devastating the major vessels, including his aorta. Quick thinking by the medic on site saved his life.

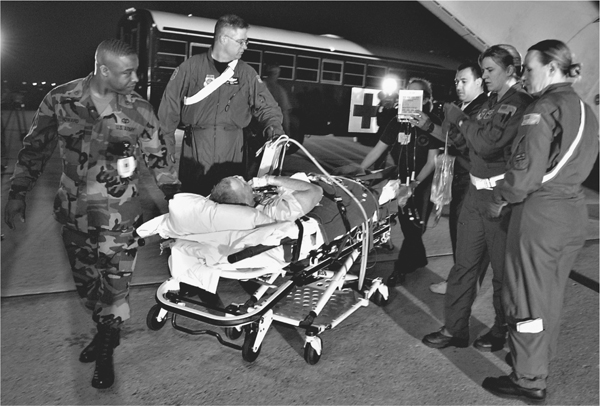

NAVY PHOTO

The soldier was in the turret of a Humvee when he thought they had hit a bump in the road and he lurched backwards. In fact, he had been shot. As he squatted down inside the hatch, his vest opened just enough for him to spray the inside of the vehicle with blood, splattering the driver who immediately alerted the medic on the radio. The shot entered just at the crease of his body armor at his left shoulder, and when he had his arms across his chest holding his weapon, he had inadvertently applied pressure to the wound. But when he squatted down, he relieved the pressure and the aorta was open, like a burst water pipe!

So, after the anesthetist finished his report, this young specialist began to wake up. He was a bit groggy at first but soon came around. Though he was battered and bruised and bandaged up, I couldn’t help but notice his reddish hair and freckles, a typical cornfed beau. I told him about his surgery and that he was safe and should be heading to Landstuhl soon, and he asked if I could call someone back home for him. He gave me his parent’’ number and I dialed it for him. I waited for it to connect, then ring, and his dad answered the phone. I identified myself, and told him where I was and said, “I have someone here who wants to talk to you” and handed the phone to his son.

They talked and the wounded soldier reassured his dad he was okay and his arm was “fixed” without really comprehending the seriousness of it all. He was certainly glad to be alive, but then he fought back tears and handed me the phone back and said, “He wants to talk to you.” I spoke with his dad briefly and answered his questions about his injury and the surgery. I could tell it was all a shock because he measured his questions carefully, and there were long pauses each time I answered him. He appreciated my honest assessment, then we hung up and the specialist had by then composed himself and asked a few more questions about his surgery and requested something for the pain.

We prepared him for transport and within a couple hours, we had him packaged up and ready to head to Germany. I said my goodbyes and reassured him he was going to do well and not to fret but to get better and tell his story to his new and up-and-coming crew.

Well, the story doesn’t end there. It only gets better. Fast forward to the fall of 2007. I had returned to Walter Reed Army Medical Center and went right back in the surgical intensive care unit I had worked in prior to deploying to Iraq, and I had recognized the early symptoms of burning out.

I had been caring for blast injury and critical casualties since 2004 when the war had started, from Landstuhl Hospital in Germany, where the critically wounded from Eastern Europe to the Middle East were evacuated; then I attended the intensive care course at Walter Reed in Washington, DC, and remained there to work in the surgical ICU. After six years caring for blown up, blasted, burned, and mangled soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and civilians (including innocent children and enemy combatants), I needed a bit of a break. I asked my chain of command if I could do a little something different for a short while. Not long, just enough to recharge, most importantly so I wouldn’t burn out. Of course, this was the time Walter Reed was under the microscope with the wounded warriors and the barracks issues, with the national press corps scurrying around trying to dig up dirt after some family members complained of the living conditions in the barracks. There was some justification for their complaints, and the attention did result in upgrades and improvements. But at this time, when I desperately needed to unwind, no one was going anywhere. However, I was hand selected to be a case manager and one of the original crew to stand up a new unit, the Warrior Transition Brigade.

It was a new concept, to change the focus back to the rehabilitation of the wounded warriors, and I was responsible for thirty-two of our nation’s heroes and the management of their outpatient care. One of my soldiers was not at Walter Reed but was located in a civilian facility at the Boston Spaulding Rehabilitation Center, and his father insisted that his son was going to get the best care available, including specialized rehabilitation. So, as a good case manager, I needed to lay eyes on this soldier.

I had been corresponding weekly with my soldier’s rehabilitation case manager, the hospital director, and the doctors involved with planning his care. I also worked very closely with the family. So in my weekly phone calls and emails, someone came up with the idea that I should go up and see my soldier and I agreed. I needed to lay eyes on him and ensure they were being totally honest with me, so I could accurately determine the best course of action and discuss his rehabilitation plan with his care team. The wheels started turning on getting me up to Boston, and this facility was so very excited that I was coming. They made all the arrangements including flights, hotels, and meals. So, when I presented this plan to my chain of command, they were thrilled and quickly approved my travel request.

This all happened the first week of December of 2007: On Saturday, December 1, I got married. On Sunday, December 2, I packed my bag and on December 3 I was in Boston. Soon after I arrived, I took a taxi to Boston Spaulding Hospital. It was a very nice facility, and I was greeted by the hospital administrator and her staff. She took me up to the unit where my soldier was accommodated. My soldier’s father was a very prominent man with lots of connections, and when I finally caught up with my soldier and his family, they were in the day room where he was participating in a sports presentation during which he was allowed to wear one of the rings the Boston Red Sox had recently earned as World Series champs and got to hold the trophy the team had received. After things settled down and we went back to his room, I finally had time to really assess my patient and his family.

“Our role, with any of our seriously injured soldiers coming in, is to do emergency surgery, and stabilize them for their quick transition out of Iraq and on their way to the American hospital in Landstuhl, Germany.” AIR FORCE PHOTO

The hospital administrator had arranged a full board review for me about this soldier, including his physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, neuro-intensivist, dietitian, and pharmacist. There were about fifteen people in attendance to discuss all aspects of care for my patient. After that was done, the hospital administrator asked me if I would mind doing an impromptu presentation to the staff members about how to best facilitate military patients and their families, as this facility was anticipating more military patients in the future. Of course I said yes, and as I entered this room, I was amazed at how many people were there. It was standing room only with approximately sixty people jammed in like sardines. I was a bit taken aback but soon pulled some thoughts together and just began speaking. I sensed they had little experience dealing with military casualties, such as blast injury patients—something I saw way too much of. Nor were they knowledgeable about integrating the military family members as part of the rehab team. We have learned that they are a vital player in the wounded warrior’s healing process.

Halfway through, I told the story of the young specialist with the severe shoulder injury, of course leaving out his name, and as I finished, a hand was raised in the back of the room. It was an older gentleman who I thought had a question. As he spoke and stepped forward, I knew exactly who he was . . . he was the father I’d spoken to the day his son was injured during my deployment to Iraq. He said, “You are the angel who said my son was alive and I would recognize your voice anywhere!”

You could have heard a pin drop in the room. I was teary eyed, he fought back the tears, and I don’t think there were too many dry eyes in the room after that. As he made his way forward, I met him with a huge hug and we both just cried and comforted each other. (I was personally gratified to know his son, my former patient, had returned to duty, despite some physical restrictions that required continuing rehabilitation. Dad joked that his son has a hard head and often pushes himself to the limits, so he wasn’t at all surprised.) Of course I realized I was still in front of all these people and had to finish my presentation, so I tied it all together, saying we live in a small world and we are all tied together, and through caring and compassion we can come together and help each other along the road to recovery.

Once he was stabilized, the patient was prepped for transport, eventually ending up at the Army’s Landstuhl Hospital, adjacent to Ramstein Air Base in Germany.

At the time of my deployment in Iraq, I was a young Army captain working in a variety of positions: day shift team leader, charge nurse, and staff nurse working with critically ill patients. I had a total of eighteen staff members and one hell of a great head nurse named Maj. Christian Swift. From that deployment, I and three other of my closest nursing friends found the loves of our lives and all of us are happily married, and some have started beautiful families. I am still in touch with my extended Army family members, and we don’t go very long without talking or visiting each other. Our takeaway from our experiences in Iraq is that life is just too damned short to waste it on petty BS. We live our lives to the fullest and try damned hard not to have any regrets or any “shoulda, woulda, couldas” in our lives. If we want to go and see or do something, we plan it and do it, because we just never know what tomorrow holds, so we live today as if it were our last.

—Army Maj. Virginia Vardon-Smith, ICU Nurse

In the eyes of a little child, already terrified of the bright lights and strange smells of a US Army hospital, and so many people in pastel-colored pajamas—to them scrubs look like PJs—coming and going at all hours and odd machines sounding like burps and beeps . . . it can all seem very scary. But imagine what a hospital must seem like to a child who’s never been to one before, especially one with so many Americans and others there speaking an unfamiliar language. And despite everyone smiling— some maybe smiling a little too much—there’s always one of them lurking around with that deadly weapon, what looks like eighteen inches of instant pain, to be avoided at all costs . . . the hypodermic needle.