A Quiet Conversation

For every service member—enlisted, NCO, or officer—there are some drudgeries of military life that cannot be avoided. In basic training it’s KP, or kitchen police, and fire watch, fighting to stay up at night while everyone else is snoozing. For me it was my turn as administrative officer of the day at the Army hospital in Frankfurt, Germany, one night in 1986. On any normal night, it would require walking the grounds and the hallways with a sergeant, ensuring doors that should be locked are locked, escorting meandering patients back to their rooms, making mundane notations on the duty log. Nothing exciting.

As the hospital dietitian I wasn’t exactly an imposing deterrent to anyone who might wish to storm the compound. I only hoped the young sergeant pulling watch with me that night was trained in hand to hand if it was required. Neither one of us though was trained to deal with what would unfold later that night.

There was a news bulletin that said the La Belle discotheque in Berlin had been bombed. It was a popular hotspot for off-duty service members, which is why it was targeted. Initial reports said that hundreds were wounded, but then we learned that two had been killed instantly—a twenty-one-year-old Army sergeant and a young Turkish woman. (A few months later another soldier died of his injuries.) Anytime one of our own is wounded or killed anywhere, it hurts, but for me, I was pregnant and I immediately thought of that young soldier’s mom.

Little did I know at the time, but part of our duties that night was to receive the deceased soldier from Berlin and ensure he was “prepared” to be sent back to the States for burial. The body was flown from Berlin’s Templehof Airport to Rhein Main in Frankfurt, then brought to us via military ambulance. As we stood there at the receiving dock, my sergeant and I had no idea what to expect. We knew one of our own was coming in, but I guess I never realized the damage a point-blank bomb blast can do to a human body.

The ambulance pulled up and my first shock was seeing the sealed body bag. Minutes later, as we unzipped it, the smell of burnt flesh was overpowering. His head was wrapped in a plastic bag and his gold necklaces were embedded in the charred skin. His body was not intact, and we had to make a notation, including a list of all his personal effects.

I maintained my professionalism, but kept constantly thinking of this young soldier’s mom, who would never again hug her baby. I carefully removed the bag from his face, and with respect and reverence, I cleaned him as gently as I could. It took me hours, and I asked him where was he from? And did he have any brothers and sisters? He was only a few years removed from high school, so I asked if he’d played sports. He looked so young, certainly too young to die. And was there anyone special in his life? (I hoped there wasn’t, because I feared she would not be able to handle the loss.)

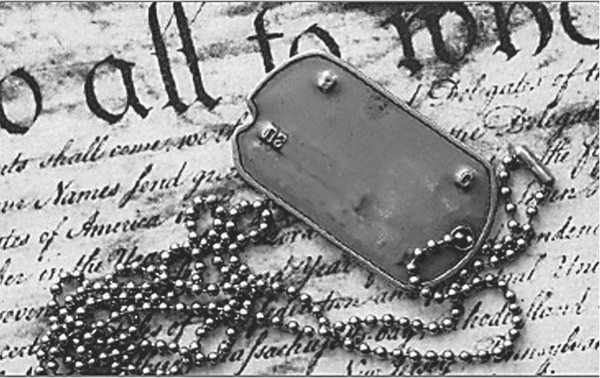

A terrorist bombing took his life. She had the difficult task of prepping his body for the trip home. “. . . constantly thinking of this young soldier’s mom, who would never again hug her baby . . . I tried to make him as presentable as possible. . . .” NAVY PHOTO

We spent hours together that night, and even though I knew he couldn’t say anything, I asked what his favorite sports teams were. And why did he join the Army? Of course I made up his responses, as if we were having a quiet conversation.

It took nearly all night as she carried on a conversation with the young soldier, fighting back tears, knowing his mom would never get to hold her baby again.” She placed all of his personal effects in a plastic bag to accompany the body home. ARMY PHOTO

I carefully dug out those gold chains from his neck and chest, not wishing to cause him any more pain, and I tried to make him as presentable as possible. My battle buddy that night contacted the soldier’s first sergeant in Berlin so we could get all of his ribbons and awards on his uniform, which accompanied him to the funeral home stateside.

I did not understand the process at the time, so I wasn’t sure when this fallen warrior’s family would actually “see” him, but I tried to make him look as peaceful and cared for as I could, in the event they were there when he arrived the next day. It took practically all night, and I was exhausted by the time I said goodbye to him, not really knowing who he was, but I knew I would never forget him. In the days after the bombing, Libyan terrorists took responsibility.

This young sergeant did not fall on a battlefield, but he died for the same reason our warriors are on distant battlefields today, the same reason our citizens are dying on our own streets, and the same reason there is a memorial where the Twin Towers once stood. That reason is known simply as terrorism.

Several days after the bombing, Armed Forces Network in Germany broadcasted a basic training graduation photo of my sergeant. And finally, that is when I cried. The handsome face on the screen looked nothing like the young man I spent hours with in the depths of Frankfurt hospital. Soon after, People magazine featured him and quoted his mom, who said the mortician needed a lot of wax and makeup to reconstruct his handsome face, which had been badly burned in the bombing. Though it’s been more than thirty years since that night, there is barely a day that goes by when I don’t look at my own handsome son, feel blessed to have him and hug him whenever I want, and then I remember “my sergeant.” And I wonder if his mom thinks of him as often as I do. But of course she does.

—Army Col. Debra D. Berthold (Retired)

Submarines are intended to glide through the oceans, silently, undetected, like a teardrop in a rainstorm. They can lurk offshore in enemy waters and no one even knows they’re out there, then vanish without a trace, pop up half a world away, and rain down thunder with devastating efficiency. What they’re not supposed to do is shake violently, but that’s what happened in January of 2005, just before noon, when one of America’s most lethal weapons hit an underwater mountain.

James Akin was the Navy corpsman on board a US Navy submarine when it collided with an undetected rock formation. He remembers how events unfolded over the next two days.