Collision

Afew seconds after that initial hit, our sub jolted again and I heard everyone asking if anyone was hurt. Almost immediately the intercom announced there were injured personnel. Multiple injuries. As the corpsman on board, I rushed up to the Combat Systems Equipment Space area of the sub and immediately saw blood everywhere, and two of the sonar technicians had severe head and facial lacerations.

While tending to their injuries, the intercom announced more casualties in the upper-level engine room. I rushed through the passageways and when I got to the engine room, one of the sailors was being helped to the forward compartment. But at the same time I was told about another injured sailor in the Main Sea Water Bay. I found him unconscious and in the fetal position so I called out for my emergency response bag, a stretcher, and a C-collar to secure his neck and spine. He was breathing on his own but it was labored. His eyes were swollen shut and blood was oozing from his nostrils.

By the time the stretcher was brought forward, other shipmates had arrived to assist me with stabilizing him. Once we had him secured on the stretcher, we carried him through the passageways, up a ladder, and into the crew mess room, which had broken dishes and food scattered everywhere due to the violent shaking of the sub. Once there I decided to do triage in the wardroom. With so many injuries, I needed assistance, so I asked Lieutenant JG Litty to run triage, while I worked on the more severe injuries. I directed that all my medical supplies be brought forward and we quickly needed all of the table tops and benches for the wounded, and even the salad bar station was cleared for my supplies.

I concentrated on Machinist Mate Second Class Ashley, who was the most critically injured, using a Propaq to monitor his vitals. I started an intravenous line and gave him oxygen. While checking him out, I was told of another injured sailor from the engine room. He was alert, but hesitated when answering questions, and complained of neck and back pain. As a precaution I put him in a C-collar and placed him on a spine board so we could carry him to the mess room, where I could start an IV and monitor him.

The crew of the US Navy submarine San Francisco enjoy some well-deserved leisure time while cruising the Pacific. Very soon their travels would take an unexpected and tragic turn. NAVY PHOTO

I checked on Petty Officer Ashley, who was on a third and fourth bag of fluids, but I finally got his ins and outs balanced. With assistance from other shipmates, we got Ashley cleaned up but then we started running into issues with the new suction machine and our oxygen supply. We quickly discovered the suction machine would not seal tightly, so we had to jerry rig a new tube and seal it with tape. Just as we solved one problem with the suction machine another one popped up, and I was running out of oxygen and needed to connect Petty Officer Ashley to the ship’s oxygen banks.

Directions from Commander Task Force 74, CTF 74, were to use oxygen from the executive officer’s stateroom and from the mid-level head (the latrine, for all you non–Navy and Marine types!). But neither of these locations were viable for Petty Officer Ashley, so we had to jerry rig another oxygen source from the crew’s mess bleed station. It required an oxygen mask, and as much Tigon tubing as we could find on the sub, secured together with duct tape. To ensure the right amount of oxygen, the bleed line was slowly opened while I felt the oxygen flow until it was at an acceptable rate. More duct tape prevented any leaks and from that point on we had a sufficient supply of oxygen.

Five hours after the incident, I gave Ashley the first dose of mannitol. His vitals were about 200/100, pulse of 140, and respirations of about 52 and shallow. After the mannitol, his vitals came down to about 140/68, pulse around 90, and respiration in the 40s. I was feeling a little more comfortable with his condition, so I wasn’t too worried about leaving him while I checked everybody with lacerations, irrigated their wounds, and redressed them properly. Some had deep lacerations that had to be sutured.

After dinner, I gathered up all my sutures, suture kits, and lidocaine. It was already a very long day, and I still had a lot of work to do. A CD player was brought in and the music helped calm down everyone. I was still most concerned about Petty Officer Ashley, who responded favorably to some of his favorite songs. Until this point, someone had to hold the oxygen sensor directly on his hand, and even though he had his arm splinted for the IV, they still had to hold it to keep him from moving around.

This was also about the time we switched communications from CTF 74 to Commander Submarine Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC). With so many casualties, I needed guidance from an undersea medical officer to ensure everyone got the treatment and meds they required. But the communication switch resulted in excessive delays and I had to repeat and repeat again vital stats then wait several minutes for instructions. It felt like I was receiving no more help and I was still on my own. I was most concerned about Ashley’s facial swelling, but the only guidance I received was to put ice on it, which to me seemed like a very inappropriate comment to be made for the dire situation this sailor was in.

After their sub collided with an undersea mountain, there were numerous injuries. “I found him unconscious and in the fetal position so I called out for . . . a stretcher . . . and a C-collar to secure his neck and spine.” NAVY PHOTO

I ended up suturing seven shipmates and finally finished around 2300 hours, though I was interrupted several times to tend to Petty Officer Ashley. I was also given permission to take the second sailor with an injured neck off the backboard, but we left the C-collar on as a precaution.

I returned to Ashley, who remained my priority patient, and I gave him a second dose of mannitol. I was also given direction to administer 5 mg of morphine, though I was hesitant to do that because I was not sure how he was going to react to it, and it was just after midnight before I gave that dose.

Before giving him the morphine, I had everything ready to intubate and ensured that my cricothyrotomy kit was close by. His vital signs had been rising slowly throughout the night. Once I gave the dose of morphine, the vital signs returned to a normal range and his respiration went down to about 40 and was no longer labored.

I felt confident he was out of danger, so Mr. Litty and I agreed to sleep in shifts. I would hit the rack first, with instructions to wake me if my assistance was needed. We had been informed that assistance would be arriving around 0300 hours, but at that same time, Petty Officer Ashley started to take a turn for the worse. The morphine (2.5 mg every hour) was not helping with his vital signs, and we began suctioning his airway.

Around 0330 hours we received word that assistance would not be arriving until possibly sunrise, which was about 0700. It had been a long day and night and we were all exhausted, but we were holding up fine. When I checked on Ashley around 0400, I noticed a massive amount of facial swelling and had to release C-spine precautions to relieve some of the pressure. Forty-five minutes later I received a message from COMSUBPAC to stop administering the mannitol, without knowing exactly why they gave this order. The mannitol, I believed, had been helping, but without it, his vitals were getting worse. By 0700, we found out there was going to be an additional delay, and we did not know when they might arrive.

Finally at 0930, we had additional medical assistance onboard. The first person was a SEAL corpsman, followed by an undersea medical officer from the USS Cable who had been a SEAL before going to medical school. The last person down was a search and rescue swimmer. It was quickly determined that Petty Officer Ashley needed to be transferred to the naval hospital at Guam with extreme urgency. A trauma surgeon was mobilized with the medical teams but left on the helicopter to manage him. We wanted to establish an airway before prepping him for the medevac helicopter. We attempted to intubate twice, but both times the critically injured sailor vomited. At that point an incision was required for the airway and the tube was put in, but the cuff on the tube would not hold air so it had to be replaced with another one. This one wouldn’t hold air either so a third tube was required. This one held air and was sewn into place.

At this point, we started securing him for the flight outbound. To make it easier to carry the litter up the narrow ladders, handrails were removed and the passageways were cleared. At several points on the sub, such as the ladders, there were several people assisting with the movement of Petty Officer Ashley.

Once he was secured to the stretcher, we started the meandering trip to the command passageway to wait for the medevac helicopter. I led the way through the narrow passageways, which only permitted two people to carry him. At several points, to get him around tight corners, we had to stand him up and during all the jostling, the surgical airway was yanked out. Once we got to the command passageway, the airway was reinserted and sewn back in. Other shipmates were busy rigging the bridge access trunk with a pulley system so we could pull the patient up through the hatch.

Once again though, the airway was yanked out and Ashley had to be lowered back down so we could replace the tube three more times due to faulty cuffs. We finally used a commercial endotracheal tube holder, which is not designed to be used for surgical airways, but miraculously it was a good fit. This time Petty Officer Ashley was hyperventilated before being hoisted up.

Everything was going well during the lift until we reached the bridge access trunk, where the stretcher got stuck. At this point we were all thoroughly frustrated, and reluctantly lowered him back down, again. By this time the medevac helicopter was hovering overhead, and the trauma surgeon was lowered to the boat. He put in a new airway and sewed it in place.

Despite the Mayday call, it took a full day for a medevac chopper to finally arrive the next morning to lower more medical personnel and to fly the injured patient to the naval hospital at Guam. NAVY PHOTO

At this time, Mr. Litty and I dashed back to the crew’s mess to get the medical supplies for the trauma surgeon, who reevaluated the patient and could not find a pulse or blood pressure. At that point, CPR was started, and one of our shipmates was doing compressions while another kept bagging to keep oxygen flowing to his lungs. Extreme measures were maintained for thirty minutes, but finally the trauma surgeon pronounced Petty Officer Ashley dead.

Initially I was so numb, overwhelmed, and simply worn out that it didn’t hit me that one of my close friends had perished, and just when we were so close to moving him off the sub to a hospital better equipped to take care of him. There was still so much to do and many shipmates to take care of, so I couldn’t afford the time to mourn.

(It would be several days later that the loss of Petty Officer Ashley finally hit me, and it was especially hard because he was a friend, and his life was in my hands. Days later the medical examiner determined he had sustained mortal injuries and would have died even if a Level I trauma center was readily available. He was surprised I managed to keep him alive for two days.)

Our deceased shipmate was taken to the wardroom to be cleaned up and placed in the refrigerator until we could arrange his transfer. I briefed the other medical personnel now on board as to the rest of the patients. Once we discussed every patient, I was told to hit the rack. I went to take a shower and change out of my poppie suit, which was soiled with blood, vomit, my own sweat, and other things I don’t want to think about.

Just getting the critically injured shipmate up to the conning tower was a logistical nightmare, trying to maneuver his stretcher down narrow passageways and up tight stairways. Handrails had to be removed and a pulley system jerry-rigged to haul him up to the waiting helicopter. NAVY PHOTO

I tried to lay in my rack, but I couldn’t fall asleep. Not after that night from hell. I tried a couple of times before we pulled in but finally gave up. Mr. Litty, who had been with me throughout the chaos, didn’t get any sleep either. It would be another twenty-four hours before we pulled in to port. By then, all the patients who needed to go to the ER were identified and prioritized, thirty all told. The most critical were transported by ambulance, the others by medevac buses and vans. As soon as the lines were secured, I went topside to coordinate the transport and treatment of the crew. I was surprised at the numerous medical teams waiting on the pier to assist. They came from the naval hospital at Guam and the USS Cable and other ships in port. Once all of our shipmates were on the way to the hospital, I hopped in the last van to catch up with them.

The emergency room was ready to receive all of our patients and had triage set up to handle our numerous injuries. The patients who had broken bones had x-rays and then went to Ortho while other patients remained in the ER. By the end of the night all patients had been seen and three had to be admitted.

—James Akin, Navy Corpsman

(The after-action review of the medical care during this incident resulted in several changes command-wide. Endotrachial tubes were added to the supply system. There was an oxygen regulator made to fit the ship’s oxygen system on the crew’s mess. Petty Officer Ashley could not fit through the bridge hatch opening while strapped to a stretcher because it would not open to 90 degrees, so modifications were made to ship bridge hatches. There was also fleet training implemented. Despite all these changes though, ultimately Navy Corps-man James Akin lost a close friend, a friend he still thinks about today.) Military doctors have to deal with more traumatic injuries in a single deployment to a war zone than most of their civilian counterparts cope with during a lifetime in the ER. Col. Stanley Chartoff was a physician on a critical care air transport team, accompanying wounded warriors on Air Force flights from the war zones of Iraq and Afghanistan to Ramstein Air Base in Germany for surgery at nearby Landstuhl Hospital. During one of these medevac missions, his team was faced with a puzzling case with potentially deadly consequences.

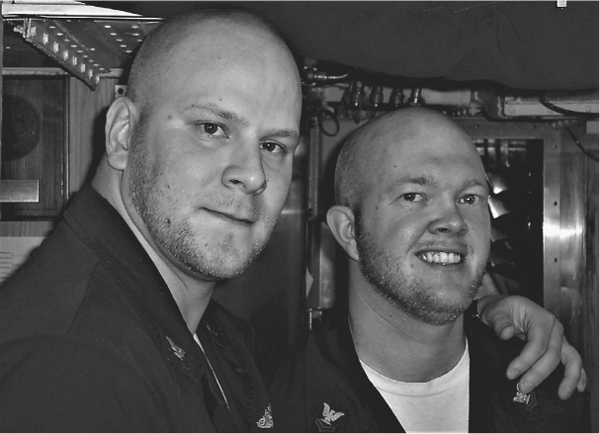

Navy Corpsman James Akin with Petty Officer Joey Ashley, who succumbed to his injuries after their submarine hit an underwater rock formation. JAMES AKIN PERSONAL PHOTO