Richard

Richard was an unexpected patient. He wasn’t serving in the Area of Responsibility where I was deployed; nor was he one of our typical battle casualties, a victim of the many improvised explosive devices in Afghanistan or a contractor with a critical medical issue. Instead, he was listed as DNBI (Disease Non-Battle Injury) off a ship in the North Atlantic, two continents away. Richard would end up challenging my physical endurance as well as my medical and leadership skills, significantly influencing my professional life, ever after. His mission also provided an unexpected respite during the insanity of war that greatly helped my psyche, if not that of my teammates.

This story actually starts two days before I met Richard, at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. It was September 2003, two months into a four-month deployment for Operation Enduring Freedom. This was my second post-9/11 deployment as a critical care physician on a three-man CCATT (critical care air transport team). My civilian specialty is emergency medicine, but the Air Force considers me a critical care doctor. My teammates were Shawn, an emergency room nurse, and Rich, a respiratory therapist, and all of us were from the same Reserve unit stateside, and this was my second CCATT deployment with Shawn in just over a year.

The mission where I would eventually meet Richard started out much like many others I had performed that summer. There were rumors that a Danish soldier was in the Army combat support hospital with a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in his lung. That rumor was confirmed at the hospital’s morning report the next day, so my team assembled our gear to get ready to transport the Dane, who called himself Snoopy, to Landstuhl Army Regional Medical Center in Germany.

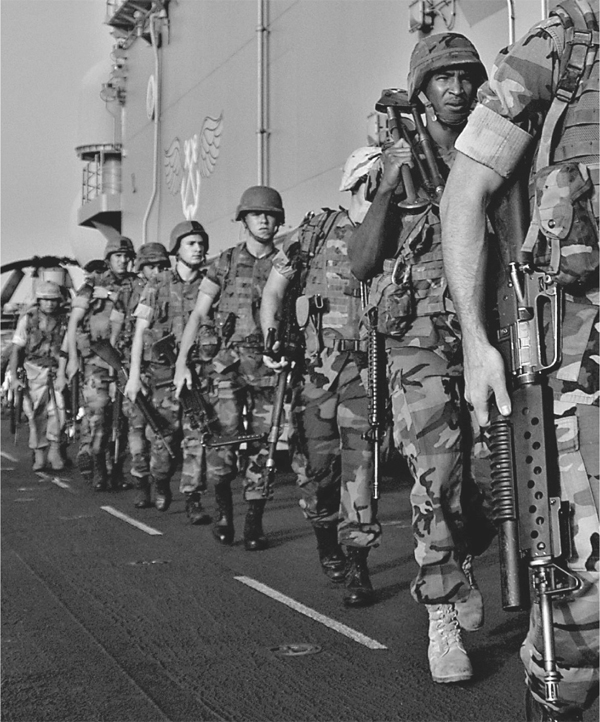

A contingent of Marines arrived in Liberia in 2003, but soon developed fevers and respiratory symptoms after working in a warehouse. Some tested positive for malaria, and there was a chance they had come in contact with other deadly viruses in West Africa. NAVY PHOTO

So what’s the connection between this patient and Richard? If it were not for Snoopy, our team would not have been in place when circumstances created the opportunity to take the mission where we met Richard.

The seven-hour C-17 flight to Ramstein Air Base was uneventful. An ambulance transported Snoopy and our team on the short ride to Landstuhl. An Air Force ground crew brought us to our hotel, the Hotel American in the city of Ramstein. I had a few beers with the rest of the crew in the lobby, then went to my room, called my wife, and went to bed. It had been twenty-two hours since I had begun my day, in Afghanistan.

Two hours after my head hit the pillow, I got a call from the Crew Management Cell, telling us they needed an extra critical care team for a mission to Liberia and we were the only one available. It was 0500 local time. They told me to be ready to be picked up in front of the hotel in thirty minutes. I quickly got dressed, woke up Shawn and Rich, gobbled down food from the hotel’s breakfast buffet, and got on the van for the ride back to Ramstein Air Base.

There we learned about a detachment of Marines stationed in Liberia who had developed fever and upper respiratory symptoms after cleaning a warehouse on the docks. Some had tested positive for malaria, but there was concern for leptospirosis and Lassa fever—a deadly and contagious disease of West Africa.

We were told there were fifteen total casualties, seven of those on litters. None of the Marines were on ventilators, but they wanted two critical care teams onsite, just in case. The other team was based at Ramstein, and they needed us because all the other Ramstein teams were stuck at Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, DC. They had gone there on other missions and were waiting for return flights to Germany.

Seven hours after I received the wake up call, the C-17 finally left Germany for an eight-hour flight to Liberia, a typical case of hurry up and wait. It was late afternoon when we landed at the airport in the capital city of Monrovia. It was warm, but not as humid as I expected. This was my first exposure to the African continent. The terminal had a Third World look about it and armed Ravens surrounded the aircraft for security.

The Marines would be arriving from the battleship Iwo Jima, which was stationed just off the coast in the North Atlantic Ocean. Soon, three silver Chinook helicopters appeared in the distance, coming closer and landing across the runway from the C-17. A Navy corpsman walked over to give us a report of the casualties, as the Marines were unloaded from the helicopters. It turns out there were actually a total of thirty-one ill Marines, two of them listed as critical.

Carey, the other critical care team doc, and I decided to split the two critical patients and consult on the others, who were assigned to the regular crew, as needed—especially since many of those were on intravenous quinidine, an anti-malaria medication that can affect the heart. My team took the sickest patient, Richard, and Shawn and Rich got him situated on a litter stanchion on the left side of the aircraft.

Richard was a nineteen-year-old lance corporal with brown hair, blue eyes, and a muscular swimmer’s build. His patient movement request let us know he had been exposed to human and animal feces while cleaning a warehouse three weeks earlier. He had been running fevers as high as 103 degrees for the past two days. He also had diarrhea and was becoming confused. A malaria smear performed on the Iwo Jima was positive for falciparum malaria, but there was still the possibility he was infected with leptospirosis and maybe even Lassa fever. He was started on anti-malarial medication and antibiotics, but his condition was worsening.

Sick bay on the battleship Iwo Jima was overflowing with Marines. Once the critical care air transport team arrived from Germany, thirty-one Marines were transported via Chinook helicopters to the airfield, where the Air Force C-17 was waiting to take them back to Bethesda Hospital, near Washington, DC. MARINE CORPS PHOTO

I first met Richard as the Navy crew brought him onto the rear ramp of the C-17. He had a baby face with a mop of brown hair, cut to Marine standards, and pale, hot, dry skin. His blue eyes were open and he could tell me his name, but not much else. He appeared agitated and was pulling on his intravenous lines, requiring us to place soft cuffs around his wrists as restraints.

We placed an oxygen mask on his face and heart monitor wires on his chest. His heart was racing at 120 beats a minute and his temperature was 102.4 degrees. We did not have time to do much else, as we had to make sure Richard, ourselves, and our equipment were secure for takeoff.

The mission was to deliver the Marines to Bethesda Naval Medical Center, just outside Washington, DC. The first leg was a two-hour flight to Dakar, Senegal, for refueling and to exchange front-end crews. The aircrew had work hour and rest cycle requirements that did not apply to the critical care teams. Richard continued to be agitated, requiring me to order Shawn to administer several doses of Haldol, a sedative.

While Richard was one of the sicker patients I have transported, at least he was whole. Most of the critically injured patients I have taken care of were missing one or more limbs from IED explosions or gunshot wounds. It felt odd not having to deal with that during this mission.

After landing in Dakar, Richard’s condition continued to deteriorate. I had not had much experience treating malaria and those I had seen were nowhere near as sick as Richard. These were pre-iPhone days, so I had to rely on the few reference books I brought with me as well as my own medical instinct. I needed more information, and our equipment included a portable blood analyzer. Rich drew a small amount of blood from an artery in Richard’s wrist and placed it in the machine. What it showed was that Richard’s blood had a critically low level of oxygen and that he was severely anemic. This could have been one of the reasons he was so confused, as not enough oxygen was getting to his brain.

Richard was already on the maximum amount of oxygen he could get from a mask, so I decided he needed to be placed on a ventilator. My team assembled the medications and equipment we needed to place a tube into his trachea. However, this was the first time I had performed this procedure on a real patient on a C-17 and I learned a valuable lesson. We had a litter in the upper position of the stanchion over Richard to hold equipment. What I found out is I could not get the proper line of vision with that litter in place to pass the tube down his throat. I kept my cool, however, and we got other crew members to move the litter while I stayed in position and passed the tube. Mission success! That need for situational awareness is something that has stayed with me ever since.

My team was finishing with getting Richard stabilized when I heard a commotion on the other side of the cabin. One of the Marines in the noncritical group had suddenly become unresponsive. He was breathing okay, but was not responding even to pain. Carey, whose other patient was very stable, took charge and set him up to be intubated as well. He almost had the same mishap I did, but I coached him along, knowing he was a cardiologist and hadn’t done this procedure very often.

Now we still had to address Richard’s other problem, which was severe anemia. He needed a blood transfusion, and it couldn’t wait till we landed stateside. I had no idea where I was going to find suitable blood in Dakar, and we only had about an hour left before we had to take off again. At this point, a young man in a Hawaiian shirt spoke up and said, “I can get you some blood.”

I had my doubts, but he identified himself as an Air Force flight surgeon assigned to the Liberian embassy in Monrovia. Because of heightened threats, he was relocated to Dakar and was staying in the local Club Med. He knew of a Navy ship at the port of Dakar that had a blood bank. He worked some magic and was able to get us two units of blood cells. The way total strangers can use trust and ingenuity and work together in foreign surroundings as a team and accomplish great things resounds with me to this day.

Thirty-one Marines had gotten sick while deployed to Liberia, and two of those were listed as critical. Once loaded and secured on the C-17 transport flight, they would be flown to the DC area for treatment at Bethesda. AIR FORCE PHOTO

We took off from Dakar for the final eight-hour leg to Andrews Air Force Base. Richard kept my team busy for most of the trip. I needed to put a special catheter in the artery in his wrist to closely monitor his blood pressure and allow us to draw blood for testing. Shawn, Rich, and I worked together to keep him sedated, keep his blood pressure under control, and adjust his ventilator to maximize the oxygen getting to his brain and the rest of his body. We continued to treat the malaria and other infections. My hope was that his body and especially his brain were resilient enough to fully recover their normal functions. I looked at this nineteen-year-old baby-faced Marine and realized he was just starting his life and had so much to look forward to when he got home. I wondered if, like most of the Marines I have met, that as soon as he was well enough, he would want to go right back to the fight.

Somewhere over the Atlantic, Rich glanced at Richard’s monitor and noticed the oxygen reading was dropping down. As any good respiratory therapist would, Rich checked his equipment and discovered the ventilator was no longer functioning. Quickly, he disconnected him and started ventilating him manually with a bag connected to oxygen. Richard’s oxygen levels improved. Looking at the ventilator, we were able to determine that a fuse was blown, but the alarm indicator was difficult to see and if there was an alarm, you could not hear it above the din of the plane. With this fuse out, the power cord did not function, so when the battery charge wore down, the machine stopped. (This same problem would happen to us again on a later mission, prompting a notification up the chain, resulting in changes by the manufacturer and the availability of spare fuses.)

As we neared Andrews, I noticed that one of the Marines whom I had seen walking around earlier in the flight was now lying down with a high-flow oxygen mask on. I asked one of the nurses about him and was told he became confused and his oxygen levels on the monitor dropped when he took the mask off. He was breathing fast even with the mask on.

I asked Rich to check his blood oxygen and it was adequate, and since we were close to landing, I decided to just keep a close eye on him and bring him with us to the ICU at Bethesda. I found out later he ended up being the sickest Marine on the plane.

Richard finally stabilized as we began our descent into Andrews. We landed and the ramp on the back of the C-17 was opened and a medical team from Bethesda came on board to meet us. When they did, our initial response was silence and nervous looks at each other because the Bethesda team was wearing protective gowns, hats, and gloves while we stood there in our flight suits.

They gave us no explanation at the time, but I later learned after a heated discussion with one of the chief flight surgeons that the medical authority at Bethesda decided not to inform the receiving team that malaria was identified as the infectious agent, and therefore not contagious. They wanted the team to exercise treating an unknown infectious disease and test their isolation procedures. I wish someone had told us it was just an exercise. Maybe our pucker level wouldn’t have spiked when we first saw them all suited up.

Richard and the other three critical Marines were moved to a bus specially equipped for critical care transfers as we prepared for the forty-five-minute trip around the Washington Beltway to Bethesda. Richard decided he wasn’t ready to let us relax, so he dropped his oxygen levels again, requiring us to manually bag him on oxygen. We also noted that his blood pressure was precipitously dropping. We told the bus driver to drive with lights and sirens as we tried to stabilize Richard. Shawn showed great skill as he prepared a drip of medication as the bus careened past the notoriously bad Washington-area drivers. As Shawn finished setting the drip up, I knelt down and noticed fluid dripping on the floor. There had been a leak in the pressure monitor line, giving us the abnormal values. Well at least we had learned how well we could perform on a moving bus.

Richard was a nineteen-year-old Marine corporal who became gravely ill in Liberia. He had numerous symptoms, but there were no definitive answers to what was slowly but deliberately taking his life. AIR FORCE PHOTO

The bus arrived at the Navy Medical Center and the two critical care teams accompanied the four Marines to the ICU. Richard was settled in his room, a welcome change from the back of a C-17, and Shawn, Rich, and I each gave status reports to our counterparts at Bethesda, and readied our equipment to return to Andrews. Richard was in very capable hands.

I could end this story here, but as a result of this unexpected mission with Richard, what happened next did so much to elevate my psyche and make the last two months of deployment bearable for the three of us, or at least I thought so at the time. Standing in the lobby of the Medical Center, I realized I was in the States again and could make an easy phone call home without dealing with overseas operators. Then we learned it was Sunday and our return flight wasn’t until Tuesday. The three of us did the math and realized we were six hours from home and it was worth the effort. We tried Union Station in DC first, but there were no trains to our destination. Instead we rented a car, arriving home at 0230. I hugged my very surprised and sleepy but happy wife and kids, then slept until morning. I had a great full day with my family, but saying goodbye again was the hardest part. Always is. Shawn and Rich reported similar experiences with their loved ones, and despite heavy traffic in Baltimore, we made it back to Andrews with plenty of time to spare as our return plane trip was delayed.

If it weren’t for our mission with Richard, I would have never had the chance to go home in the middle of a war. I was recharged and the rest of the deployment was less stressful knowing that I could look forward to returning home again. This same strength supported me during the next deployment and anytime I needed to be away from home for a prolonged period of time.

So what happened to Richard? I never did get to meet this strong young Marine in a state of wellness, but I learned from the doctors at Bethesda that he had suffered what is known as cerebral malaria, where the malaria organisms clog up the arteries to the brain causing strokes and coma. Carey’s Marine had the same outcome. Within days of arriving at Bethesda, Richard was awake and able to be taken off the ventilator. Unfortunately, his respiratory status worsened as he developed a condition called ARDS. He needed to be placed back on the ventilator for a period of days, but eventually improved and had a full recovery. I later learned that the reason these Marines developed malaria was they had not been taking their malaria prevention pills. They were prescribed mefloquine, which has known significant side effects. Also most were not using insect repellent and none were using bed netting.

After the C-17 medical transport plane arrived at Andrews Air Base, a medical team dressed in protective gear came aboard to load up the four critically ill patients for the forty-five-minute drive to Bethesda Hospital. AIR FORCE PHOTO

Richard inadvertently became a poster child for how easily and cheaply malaria can be controlled with adherence to proper precautions, and how severely it can cripple our fighting force. He was not only the one patient who has helped me become a better doctor, teammate, airman, husband, and father, but he showed the military how its response to those Disease Non-Battle Injury patients can greatly influence the protection and strength of our men and women in uniform.

—Col. Stanley E. Chartoff, US Air Force Reserves

While Iraq and Afghanistan have dominated the nightly news cycles during the past decade, there have been numerous other regional skirmishes and conflicts, some of which the average American would not be able to pinpoint on a world map. Sarajevo, Mogadishu, and Kosovo are just a few of these soon-forgotten war zones, but on occasion American military forces are called on to provide humanitarian assistance, to quell high seas piracy, or even to save a little boy.