CHAPTER 4

First Days

Jellicoe would have been happy to give England the glorious victory for which it yearned; the problem was to arrange that victory and persuade the Germans to cooperate. For more than a century after Trafalgar, the British navy possessed no detailed, carefully worked out war plan. Instead, British naval officers universally assumed that when war broke out, the fleet would immediately take the offensive. In 1871, when Vice Admiral Sir Spencer Robinson was asked how the navy would be employed in wartime, he replied, “The only description I could give is that wherever it is known that the enemy is, our ships would go and endeavour to destroy him. If you saw a fleet assembling at a stated port, you would send your fleet to that port to attack it. That is my view of the way in which war should be carried out.” This virile opinion was shared by successive Boards of the Admiralty; they restated it in writing on July 1, 1908, when the Sea Lords instructed the Commander-in-Chief of the Channel Fleet that “the principal object is to bring the main German fleet to decisive action and all other operations are subsidiary to this end.” The theme of the instant, all-out assault was drummed into the British public. Nelson had won at Trafalgar, The Spectator declared on October 29, 1910, “because our fleet, inspired by a great tradition and a great man, recognised that to win you must attack—go far, fall upon, fly at the throat of, hammer, pulverise, destroy, annihilate—your enemy.”

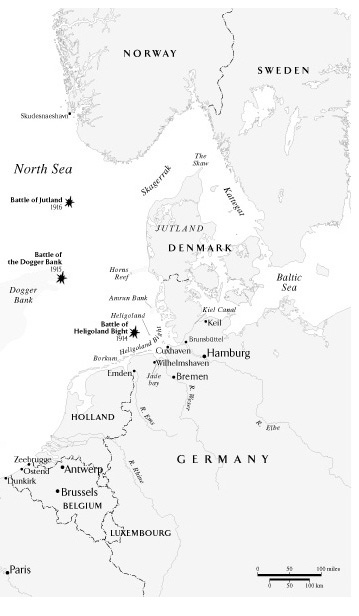

But what if the enemy refused to cooperate? Suppose, in this new war, the Germans, despite possessing the second largest navy in the world, held their ships out of reach inside heavily fortified harbors, awaiting their own moment to strike? Until 1912, when Churchill came to the Admiralty, the Royal Navy had planned to deal with this possibility just as Nelson had dealt with Napoleon’s navy before Trafalgar: with a close, inshore blockade, monitoring every action of the enemy fleet and bringing it to battle if and when it came out. This time, a close British blockade of the German North Sea coast would be established with destroyers and other light forces constantly patrolling a few miles offshore, ready to report any German sortie before falling back on the British battleships cruising nearby. Fisher was the first to recognize that the submarine, the torpedo, and the mine had tossed this policy of close blockade on the scrapheap. No British admiral would be allowed to keep a fleet of battleships cruising back and forth in the Heligoland Bight in the close and constant presence of German submarines, destroyers, and minefields. This would mean, the Admiralty explained to the Committee of Imperial Defence in 1913, “a steady and serious wastage of valuable ships.” In addition, there was the problem of fuel. Sailing ships in Nelson’s day required only the wind; steel warships needed coal and oil. Destroyers patrolling the entrance to Heligoland Bight would have to return to port every three or four days to refuel; with a third of the force always absent, a close blockade would require twice as many modern destroyers as the Royal Navy possessed.

By 1913, the British navy had accepted these realities, abandoned close blockade, and adopted a new policy of distant blockade. In essence, this meant that rather than blockading the German coast, the British navy would close off the entire North Sea. Here, geography lent a powerful helping hand. As the naval historian Arthur Marder put it, “In a war with Germany, Britain started with the crucial geographic advantage of stretching like a gigantic breakwater across the approaches to Germany”; Mahan had said the same thing: “Great Britain cannot help commanding the approaches to Germany.” The existence of the British Isles, stretching over 700 miles from Lands End to the northern tip of the Shetlands, left only two maritime exits from the North Sea into the Atlantic. The first was the Straits of Dover, twenty miles wide at their narrowest point. Here, the new technology of undersea weaponry came down in Britain’s favor. “Owing to recent developments in mines, torpedoes, torpedo craft and submarines,” declared a Committee of Imperial Defence paper on December 6, 1912, “the passage of the Straits of Dover and the English Channel by ships of a power at war with Great Britain would be attended with such risks that, for practical purposes, the North Sea may be regarded as having only one exit, the northern one.” This “northern one” was the 200-mile-wide gap at the top of the North Sea, between northern Scotland and the southern coast of Norway. In these stormy waters, the blockade would be enforced by cruiser patrols supported by the dominating presence of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. With these two exits barred, then, in the words of the naval writer Geoffrey Callender, “so long as Admiral Jellicoe and the Dover patrol held firm, the German fleet in all its tremendous strength was literally locked out of the world. The Hohenzollern dread- noughts could not place themselves on a single trade route, could not touch a single overseas dominion, [and] could not interfere with the imports on which the British Isles depended.” Distant blockade did not mean that British ships and sailors would simply sit as watchmen at the ocean gates and surrender the North Sea to the Germans. A new Admiralty war plan defined the Grand Fleet’s new role: “As it is at present impracticable to maintain a perpetual close watch off the enemy’s ports, the maritime domination of the North Sea . . . will be established as far as practicable by occasional driving or sweeping movements carried out by the Grand Fleet . . . in superior force. The movements should be sufficiently frequent and sufficiently advanced to impress upon the enemy that he cannot at any time venture far from his home ports without such serious risk of encountering an overwhelming force that no enterprise is likely to reach its destination.” This was a practical strategy to contain the threat of the German fleet, the best that could be devised with the resources available. Unhappily for British jingoists, in uniform and out, it was not a strategy that guaranteed an immediate, annihilating victory over the High Seas Fleet.

Britain’s abandonment of close blockade came as a blow to the German Naval Staff, which had planned to turn the Royal Navy’s traditional offensive exuberance to its own purposes. Most German naval officers had expected that the British navy would begin the war with an immediate effort to destroy the High Seas Fleet. “Before the war,” wrote Captain Otto Groos, the official German naval historian, “the whole training of our fleet and to some extent even our shipbuilding policy and even certain constructional details (for instance a small radius of action of a large number of our destroyers) was based on the assumption that the British would organize a blockade of the Heligoland Bight with their superior fleet.” A major attack, the Germans believed, was coming. “There was only one opinion among us, from the Commander-in-Chief down to the latest recruit, about the attitude of the English fleet,” said Reinhard Scheer, commander of the German fleet at Jutland. “We were convinced that it would seek out and attack our fleet the minute it showed itself and wherever it was.” The battle, close to German ports, might go either way, the Germans thought, but damaged German ships could be expected to limp or be towed home; damaged British ships retreating across the North Sea would be subject to further German attacks—as well as the perils of bad weather, engine failure, or rising water inside their hulls. Because of this, English losses were expected to be greater; this would help create the “equalization of forces” that the German navy urgently desired. Thus it was that when the expected British onslaught into the Bight failed to materialize, the premise on which the Germans had based their strategy was overturned. And when the British navy failed to establish even a semblance of a close blockade, German U-boats and torpedo-carrying destroyers were deprived of any ability to harass and diminish the blockading fleet.

The war had scarcely begun when Germany’s admirals and captains, robbed of their intended wartime strategy, finding the exits to the North Sea barred and the lower and middle North Sea turned into a watery no-man’s-land, discovered that they did not know what to do.

Because each side was waiting for the other to act, nothing so dramatic as the British pursuit of Goeben occurred in the North Sea during the first weeks of the naval war. The Grand Fleet went to sea under Jellicoe, spreading its battle squadrons and flotillas for miles across the gray waves. They saw nothing. On August 6, Jellicoe dispatched his light cruisers to search the coastal waters of Norway. They found nothing. At dawn on the morning of August 7, the fleet returned to Scapa Flow to coal; by twilight, it was back at sea. This routine, exhausting for men and wearing for ships, became the normal life of the Grand Fleet for the next fifty-two months.

The war’s first blow in home waters was struck, not by this enormous fleet, but by a single, humble vessel. In the misty dawn of August 5, when the war was only five hours old, the British cable ship Teleconia dragged her grappling irons along the muddy bottom of the southern North Sea. Five German overseas cables, snaking down the Channel from the port city of Emden, on the Dutch frontier, were her quarry: one to Brest, in France, another to Vigo, in Spain, a third to Tenerife, in North Africa, and two to New York. One by one, Teleconia fished up and cut all five of the heavy, slime-covered cables. That same day, a British cruiser severed two German overseas cables near the Azores. Thus, from the war’s first day, Germany was cut off from direct cable communication with the world beyond Europe.

Meanwhile, as Jellicoe’s armada cruised in the north, the light forces based at Harwich sank their first German ship—and suffered Britain’s first loss. At dawn on the fifth, Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt of the Harwich Force took his two destroyer flotillas to sea in a sweep toward the coast of Holland. At 10:15 a.m., this sortie produced a result: a British fishing trawler informed the destroyer Laurel that a vessel in its vicinity was “dropping things overboard, presumably mines.” Two destroyers investigated; at 11:00 a.m., through rain squalls, they sighted a steamer ten miles away. The vessel resembled one of the Hook of Holland steamers providing peacetime ferry service for the Great Eastern Railway between Harwich and the Netherlands. Captain H. C. Fox, commanding the 3rd Destroyer Flotilla from the light cruiser Amphion, joined the chase and soon the destroyer Lance fired “the first British shot in the war.”

The target was the 1,800-ton Hamburg-America Line excursion steamer Königin Luise, whose peacetime work was ferrying passengers back and forth from Hamburg to Heligoland. On the eve of war, she had been moved into a dockyard, repainted in the colors of British Great Eastern Railway steamers plying between Harwich and the Hook of Holland, and loaded with 180 mines. On the evening of August 4, while the British ultimatum still waited unanswered in Berlin, Königin Luise slipped out to sea with a patchwork crew of peacetime sailors and navy regulars. Her mission was to use her disguise to sow mines in the shipping lanes off the mouth of the Thames.

Königin Luise’s first mine went over the side at dawn, and others followed through the morning. Then Amphion, coming up behind her own destroyers, opened fire and by noon, Königin Luise was lying on her port side in the water. Fifty-six of a crew of 130 were rescued by Amphion. Half of these prisoners were incarcerated in a compartment in the light cruiser’s bow, for the grim reason that “if we go up on a mine, they might as well go first.”

Returning to Harwich and attempting to avoid the area in which he thought Königin Luise’s mines might be floating, Fox sighted another suspicious steamer. This vessel, like the Königin Luise, wore the colors of the Great Eastern Railway, but unlike the ship Fox had just sunk, it was flying a large German flag. Seeing this, the flotilla opened fire. The steamer quickly hauled down the German flag and hoisted the Red Ensign of the British merchant marine. Eventually, it became clear that the vessel was a genuine Great Eastern Railway steamer, St. Petersburg, flying German colors because she was carrying the German ambassador to Great Britain, Prince Karl Max Lichnowsky, and his wife and staff from Harwich to the neutral Netherlands for repatriation to Germany. The German flag had been raised to give her immunity from attack by any German ships she might encounter. Her identity and mission established, she was permitted to steam away toward Holland. Fox continued toward Harwich.

Suddenly, a mine exploded against Amphion’s bow. The explosion killed and wounded many British seamen and, among the German prisoners in the bow, only one survived. With his ship ablaze and sinking, Fox gave the order to abandon ship. Just as he did, a second explosion occurred. “The foremost half of the ship seemed to rise out of the water,” Fox said later. “Masses of material were thrown into the air to a great height, and I personally saw one of the 4-inch guns and a man turning head over heels about 150 feet up.” The cause of the second explosion was never established, although Fox believed that it was another mine. Within fifteen minutes, his ship went down. One hundred and thirty-two British seamen were killed or wounded along with twenty-seven men from the Königin Luise. Twenty-eight German prisoners were brought back to England. When Fox reached Harwich on a destroyer, his friend Commodore Roger Keyes rushed aboard and was shocked to see Fox “stagger out of the chart house horribly burnt and disfigured.”

Four days later, at the northern end of the North Sea, the next encounter occurred. Near noon on August 8, south of Fair Island, between the Orkneys and the Shetlands, the British dreadnought Monarch, conducting gunnery practice with her sisters Ajax and Audacious, was attacked by a submarine torpedo, which missed. Then, at dawn the next day, August 9, the light cruiser Birmingham sighted a submarine lying motionless on the surface in a thick fog. The U-boat was stationary, and Birmingham’s crew could hear hammering inside. The cruiser immediately opened fire and the submarine, U-15, slowly got under way. Birmingham, her wake boiling, turned and at high speed rammed U-15 amidships, slicing her in half. The wreckage sank quickly, carrying down all twenty-three men of the crew and leaving behind on the surface only “the strong odor of petroleum and . . . rising air bubbles.” It was the first U-boat kill of the war. Birmingham, suffering only superficial damage, was able to continue with the fleet. The triumph pleased the Admiralty, but the fact that a U-boat was operating so far north alarmed Jellicoe, who suggested that he withdraw the fleet from Scapa Flow to bases farther west. The Admiralty replied that this was impossible; for the next eight days, the Grand Fleet’s presence was needed to safeguard the passage of the British Expeditionary Force to France. On the morning of August 8, Churchill had signaled Jellicoe: “Tomorrow, Sunday, the Expeditionary Force begins to cross the Channel. During that week the Germans have the strongest incentives to action.”

During the period from August 9 to August 22, when 80,000 British infantrymen and 12,000 cavalrymen—with their horses—were crossing to Le Havre and other French ports, the Admiralty did not know what to expect: a surface attack by German destroyers into the Channel to savage the transports; a concentrated submarine assault on the vessels crowded with soldiers; or a massive challenge to the Grand Fleet by the dreadnoughts of the High Seas Fleet. On August 12, the bulk of the expeditionary force began to cross. During the days of the heaviest transportation—August 15, 16, and 17—Heligoland Bight was closely blockaded by British submarines and destroyers, supported by the Grand Fleet in the central North Sea. On August 18, the last day of heavy traffic, thirty-four transports crossed in twenty-four hours. During this time, the German navy did not appear. No ship was molested or sunk; not a man, soldier or sailor, was drowned. The concentration of the British Expeditionary Force in France was completed three days earlier than anticipated in the prewar plan and, on the evening of August 21, British cavalry patrols made contact with the Germans in Belgium. Three days later, the British army was heavily engaged near Mons.

The cause of this German inactivity was not known in Britain, and the stillness created fears that something terrible might be in store. These fears centered on the nightmare of a German invasion, or, more likely, a series of amphibious raids on England’s east coast. (Churchill estimated that up to 10,000 Germans might be landed.) In fact, at no time during the Great War did either the General Staff of the German army or the German Naval Staff ever seriously discuss or plan an invasion of England on any scale, large or small. The passivity of the German fleet while the BEF was crossing stemmed from other causes. Despite the kaiser’s cries of betrayal by his English cousins and Bethmann-Hollweg’s hand-wringing over “a scrap of paper,” officers in the German army were neither surprised nor troubled by Britain’s entry into the war. The Army General Staff had expected the British to come in. “In the years immediately preceding the war, we had no doubt whatever of the rapid arrival of the British Expeditionary Force on the French coast,” testified General Hermann von Kuhl, a General Staff officer. The staff calculated that the BEF would be mobilized by the tenth day after a British declaration of war, gather at the embarkation points on the eleventh, begin embarkation on the twelfth, and complete the transfer to France by the fourteenth day. This estimate proved relatively accurate. More important, the Germans did not much care what the British army did. Confident of a quick victory on the Western Front, they felt that measures taken to prevent the passage of the BEF would be superfluous. The kaiser had described the British as a “contemptible little army,” and Helmuth von Moltke had told Tirpitz, “The more English, the better,” meaning the more British soldiers who landed on the Continent, the more who would be quickly gobbled up by the German army.

The Imperial Navy thought differently, and once the passage of the expeditionary force began, many in the German fleet were anxious to contest it. The Naval Staff was surprised that the BEF was under way so early; they had not expected the cross-Channel movement to begin until August 16. This, added to its surprise at Britain’s institution of a distant rather than a close blockade, created an atmosphere of uncertainty in the German navy, which militated against acts of sudden boldness. In fact, despite the heavy protection given the Channel transports, a bold approach might have produced favorable results for the Germans. During the crossing of the expeditionary force, the Grand Fleet moved south and kept to sea as much as possible, but Jellicoe’s destroyers were constantly returning to base for fuel. A strong German attack, with destroyers dashing into the Channel to torpedo the transports, could have been attempted against the comparatively light British forces based in southern waters, with the attackers returning to Germany before Jellicoe could intervene. But without the support of heavy ships, Ingenohl believed, the German destroyer force would be massacred, and he held it back. As for submarines, ten U-boats already had gone to sea in an effort to find the British blockade line and locate the Grand Fleet. Ordered out on August 6, they were beyond wireless communication and thus could not be summoned to attack in the Channel. The German navy, therefore, did nothing.

Once the main body of the BEF was safely across the Channel, the Admiralty turned its attention to the wider seas. The threats there, besides Goeben and Breslau, were the two powerful armored cruisers of the German East Asia Squadron, and seven widely scattered light cruisers. One effective antidote to the German light cruisers would have been Britain’s fast new light cruisers, but at the outbreak of war the Royal Navy still had too few of these. “We grudged every light cruiser removed from home waters,” said Churchill, who believed that “the fleet would be tactically incomplete without its sea cavalry.” The Admiralty had to make do with other ships, older, slower, less capable. Many of Britain’s numerous predreadnought battleships were dispatched around the globe—Glory to Halifax, Canopus to Cape Verde, Albion to Gibraltar, Ocean to Queenstown—to serve as rallying points in case German armored cruisers broke out of the North Sea onto the oceans. Elderly British armored cruisers, some only a few months from the scrap yard, were mobilized and sent to sea. Twenty-four commercial ocean liners were armed and commissioned as auxiliary merchant cruisers.

In addition, there were troopships to be convoyed across the oceans. Two British regular army infantry divisions, broken into separate battalions and scattered on garrison duty around the globe from Bermuda to Hong Kong, had to be collected and brought home. Thirty-nine regular army infantry battalions from the British Indian army were to be gathered up and formed into the 27th, 28th, and 29th Divisions. They, in turn—to preserve order in India and the prestige of the Raj—were to be replaced in India by three undertrained Territorial divisions brought out from England. To the military mind, all this shuffling and exchanging, designed to place in France the best-trained soldiers Britain possessed, made excellent sense. To the navy, required to transport and convoy these thousands of men in different directions, the task was complicated, burdensome, and dangerous. Nevertheless, it was done. During September, two British Indian divisions and additional cavalry—50,000 men—were crossing the Indian Ocean bound for Europe. The Australian politician Andrew Fisher, soon to become prime minister, had declared that Australia would support “the mother country to the last man and the last shilling,” and volunteers had swarmed into recruiting depots. A New Zealand contingent waited to be escorted across 1,000 miles of South Pacific Ocean to Australia, where it would be added to 25,000 Australians and with them be convoyed to Europe. The threat of German surface raiders on the sea-lanes forced a delay in the sailing of the Australian convoy, but on November 1, the convoy carrying the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps sailed from Perth for the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

Meanwhile, two Canadian divisions were escorted across the Atlantic. The Canadian convoy sailed from the St. Lawrence on October 3 with more than 25,000 enthusiastic volunteers embarked in thirty-one ships. Detailed, uncensored stories in Canadian newspapers had followed the enlistment and training of these men, their boarding of the transports, the nature of the convoy, and its escort. With all this information freely available, the Canadian government belatedly became apprehensive for the convoy’s safety. The original close escort, a squadron of old British cruisers under Rear Admiral Rosslyn Wester Wemyss, had seemed inadequate to the Canadian government, whereupon the Admiralty added the old battleships Glory and Majestic. In addition, the Grand Fleet battle cruiser Princess Royal was secretly dispatched from Scapa Flow to rendezvous with the convoy in the mid-Atlantic and protect it against any German battle cruiser that might slip out of the North Sea. The movements of the Princess Royal were extraordinarily stealthy and her presence was concealed even from the Canadian government. Had the ship’s involvement been known, the Canadians would have been reassured, but Jellicoe insisted that the fact be revealed to no one. He had permitted the vessel to go because he understood the political disaster that would accompany any harm coming to the convoy. Nevertheless, he could not bear the German Naval Staff and the High Seas Fleet commander knowing that his battle cruiser force had been diminished by this major unit. And so it was that in the middle of the Atlantic, Rear Admiral Wemyss was astonished one day to see looming nearby the massive gray shape of Princess Royal.

Ten days later, as the convoy approached the English Channel, a U-boat was reported off the Isle of Wight. The army’s wish had been to come up the Channel and disembark the troops at Portsmouth, near the British army’s main training camps. Nevertheless, within an hour of the submarine report, the Admiralty asserted its paramount responsibility for the safety of the convoy and the transports were ordered into Plymouth, at the western end of the Channel. There, on October 14, the first Canadians came ashore in England.

With the navy’s help, the equivalent of five British regular army divisions had been carried to Europe and replaced in the Indian subcontinent by three divisions of Territorial troops from England. Two Canadian divisions had crossed the Atlantic, and, although this was not concluded until December, two divisions were to be convoyed from Australia and New Zealand to Egypt. The effect of this concentration was to add five British regular army divisions to the six divisions with which Great Britain had begun the war. By the end of November, the British army in France had been raised from five to approximately thirteen divisions of regular, highly trained troops. This did not count the Canadian and Australian divisions training in England and Egypt, the ten Territorial Army divisions which remained for the moment in England, or the twenty-four divisions of new volunteers that Lord Kitchener was raising. For the Admiralty and the navy, the important thing was that all these vast, complicated movements at sea had been completed “without the loss of a single ship or a single life.”