CHAPTER 25

The Naval Attack on the Narrows

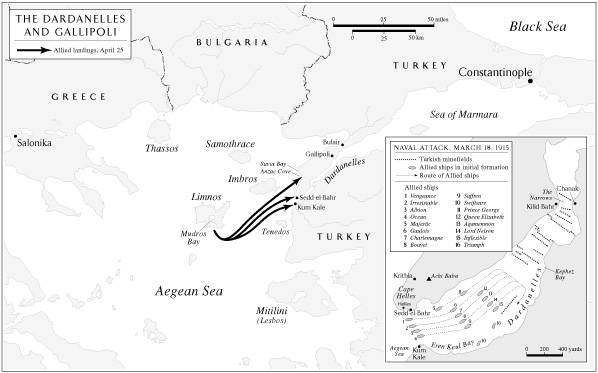

Sunrise on March 18 promised a fine Aegean morning. The sky was clear and a light, warm, southerly breeze was blowing across a sea of the deepest blue. The fleet left its overnight anchorage under the white cliffs of Tenedos and cleared for action. What followed that day was a remarkable battle involving a number of large ships in a small area of water closely confined by land. Essentially, as Alan Moorehead has written, it was “a naval attack upon an army, or at any rate upon artillery. . . . There was no element of surprise . . . and the object of the struggle was perfectly obvious to everybody from the youngest bluejacket to the simplest [Turkish] private. All hung upon that one thin strip of water scarcely a mile wide and five miles long at the Narrows: if that was lost by the Turks, then everything was lost and the battle was over.”

De Robeck’s armada of eighteen battleships steaming across the sunlit waters toward the Straits made one officer believe that “no human power could withstand such an array of might and power.” The admiral’s plan was to silence the Turkish forts and big guns at the Narrows by long-range bombardment. Once these guns were subdued, the battleships would advance up the Straits and engage the batteries protecting the minefields. As soon as the Narrows forts and the mobile batteries were suppressed, the minesweeping trawlers would advance and, in broad daylight, sweep a passage 900 yards wide. The battleships then would advance through this swept channel up to the Narrows forts and complete their destruction at close range. If, as the admiral hoped, he could batter the forts into silence by the evening of the first day, then his fleet might complete its other assignments and enter the Sea of Marmara the following day.

De Robeck planned to begin his attack with his four most powerful British ships: Queen Elizabeth, Agamemnon, Lord Nelson, and Inflexible. They were to take position side by side across the Straits at a distance of 14,000 yards from the Narrows forts and open fire at the heavy guns situated there. They would not anchor, as it had been established that an anchored ship was too easy a target for the mobile howitzers. Instead, the battleships were to head upstream, maintaining position with their engines and propellers so that they could move quickly in response to enemy fire. These four heavy-bombardment ships—which de Robeck designated Line A—were accompanied by two predreadnought battleships, Prince George and Triumph, whose mission was to engage the howitzer batteries on either shore.

Line B, steaming a mile behind Line A, was made up of the old French battleships Gaulois, Charlemagne, Bouvet, and Suffren—flanked by two more British predreadnoughts, Majestic and Swiftsure. These six ships were to wait until the Narrows’ big guns had been initially suppressed; then they were to pass through Line A and close to within 10,000 yards of the Narrows, adding their own heavy fire to that of the more modern ships. As Turkish fire diminished, Line B was to advance to within 8,000 yards of the Narrows, while behind them, Line A closed to 12,000 yards. The combined firepower of these ships would bring forty heavy guns—eight 15-inch and thirty-two 12-inch—to bear on the enemy forts. A third division, Line C, made up of four old British battleships, Vengeance, Irresistible, Albion, and Ocean, was assigned to wait outside the Straits until, on de Robeck’s signal, it was summoned forward to relieve Line B, bringing fresh guns and gun crews to grind down the presumably exhausted enemy artillerymen. Once this bombardment had silenced the forts, six trawlers would advance and sweep a passage along the Asian coast. The battleships would then come up this passage to approach and pulverize the Narrows forts at point-blank range. Two more old battleships, Cornwallis and Canopus, would accompany the minesweepers and assist by suppressing the mobile Turkish howitzers.

At 10:30 a.m., Queen Elizabeth and the other eleven battleships of Lines A and B entered the Straits in brilliant sunshine, steaming slowly forward across the sparkling water. At 11:00 a.m., Line A reached its position, 14,000 yards downstream from the Narrows, and Queen Elizabeth trained the long barrels of her 15-inch guns at the Chanak forts, seven miles away. At 11:25 a.m., she opened fire while Agamemnon, Lord Nelson, and Inflexible bombarded the forts at Kilid Bahr on the opposite shore. All of the forts were hit repeatedly and at 11:50 a.m. a heavy explosion rocked one of the Chanak forts. De Robeck judged that the time had come to move closer and signaled Admiral Guépratte to bring the French battleships in Line B forward through the British line. Passing up the Straits, the French ships spread out in order to give the British ships, now astern of them, a continuing clear field of fire. The forts replied vigorously and a tremendous cannonade reverberated through the Dardanelles. It was a dramatic spectacle in this confined space: the earsplitting crash and earthquake rumble of scores of heavy guns; the rows of oncoming gray ships moving through calm, blue water with towering fountains of spray rising above them; the forts obscured in clouds of smoke and dust until the pall was rent by the flash and roar of the Turkish cannons; the stabs of light from the howitzers firing from the ridges and gullies—all this under an intense blue sky flecked with white clouds. Every ship inside the Straits was subjected to determined fire from the Turkish howitzers and field guns. These shells could not be decisive against the heavy armor of hulls and turrets, but lightly protected superstructures, funnels, and upper decks suffered. At 12:30 p.m., Gaulois was hit by a 14-inch shell below the waterline and, leaking badly, retreated and beached herself on a small island just outside the Straits. Agamemnon was struck twelve times in twenty-five minutes and Lord Nelson, Albion, Irresistible, Charlemagne, Suffren, and Bouvet were also hit. These blows, however much they pierced and bent and twisted the superstructure of the ships, scarcely touched the men behind the armor: in the entire Allied fleet, there were fewer than twenty casualties.

Several of the men hit had not been shielded by armor. Inflexible’s fire control station, high on her forward mast, was a small platform with thin walls and a thin roof, connected by voice pipes and telephones with the bridge and the gun turrets. The gunnery officer was Commander Rudolf Verner, the same man who had watched the destruction of Admiral von Spee from this platform at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. Now, in the Dardanelles, Verner was using his binoculars to spot the effects of his ship’s gunnery when a shell suddenly exploded against a signal yard just above the fire control station. Steel fragments slashed down through the station’s roof and walls. Verner’s right hand was partially severed, his right arm “pulped,” his left arm and left leg shattered, and his skull fractured. Three seamen in the station were killed and four others, along with the assistant gunnery officer, were wounded. Verner remained conscious, saying, “Thank you, old chap,” to a man who spread a mat for him to lie on. Then, remembering that he was still the officer in charge, he raised himself to the level of a voice pipe to report, “Fore-control out of action. We are all dead and dying up here. Send up some morphia.” Rescue was slow in coming. The ship’s bridge was in flames and the steel ladder up the mast was too hot for the ship’s surgeon—who attempted the climb—to touch. A few minutes later, Verner appealed again, urgently: “For God’s sake, put out the fire or we shall all be roasted.” Eventually, Inflexible’s second in command climbed up, burning his hands severely on the ladder. Verner and the other wounded men were lowered on bamboo stretchers and taken below. Inflexible resumed firing.

By 2:00 p.m., according to the Turkish General Staff account, the situation of the artillerymen in the forts had become “very critical. All telephone wires [between spotters and gunners] were cut. . . . Some of the guns had been knocked out, others were half-buried, still others were out of action with jammed breech mechanisms.” The gunners were demoralized and their fire grew increasingly spasmodic.

De Robeck now ordered the French squadron in Line B to withdraw and Line C, the four old British battleships waiting outside the Straits, to advance. At 1:54 p.m., Suffren began turning in an arc to starboard, leading her three sisters out of the action through a bay on the Asian shore. They were passing downstream, almost abreast of Queen Elizabeth, when Bouvet, the second ship in line, was rocked by a tremendous explosion. Still traveling through the water, she heeled over, capsized, and vanished—all within sixty seconds. Watchers could not believe what they had seen: at one moment the ship was there; the next, she was gone. Her captain and 639 men were drowned; sixty-six men were rescued, having saved themselves, said a Lord Nelson officer, by running “down her side and across her bottom as she went over, like squirrels on a wheel.” As his ship rolled over, the captain’s final command had been “Sauvez-vous, mes enfants!”

No one knew what had happened to the ship. At first, observers on both sides believed that a heavy shell had exploded her magazine and Turkish gunners redoubled their fire on other ships. The loss did not deter de Robeck and for the next two hours the bombardment continued. Two by two, Ocean and Irresistible, Albion and Vengeance, Swiftsure and Majestic approached to within 10,000 yards and fired. Some of the heavy guns at the Narrows began firing again, but by 4:00 p.m. they had stopped. Keyes called for the minesweepers. Later he said: “I did not think the fire from the concealed howitzers and field guns would ever be a decisive factor. I was wrong. The fear of their fire was actually the deciding factor . . . that day.” Four trawlers passed Queen Elizabeth, heading upstream. The trawlers got their sweeps out and three mines were fished up and exploded. But then, as the trawlers came under howitzer fire, their progress wavered and, despite the attempts of their navy captains to rally the crews, they turned and ran back out of the Straits.

This embarrassment was followed by something worse. At 4:11 p.m., the battle cruiser Inflexible, still firing despite the damage to her foremast, suddenly struck a mine near the Asian shore. The explosion tore a hole in her bow, flooding a forward compartment and quickly drowning twenty-nine men. The tremendous shock of the explosion slammed the wounded Rudolf Verner against a bulkhead, further injuring his head. He began to bleed heavily again. As the ship was settling by the bow, Captain Phillimore ordered all men not engaged in engineering or damage control to come up to the comparative safety of the after deck. The battle cruiser then made her way slowly back down the Straits and headed for Tenedos; there she anchored in shallow water, her forward deck almost level with the sea. Verner, never losing consciousness, was moved to the hospital ship Soudan, where his shattered arm was taken off. “Tell my people that I played the game and stuck it out,” he said to the surgeon. Two hours later, he died. Eventually, Inflexible was towed backward (to minimize pressure on the bow interior watertight bulkheads now keeping out the sea) to Malta, where she spent six weeks in dry dock.

Fifteen minutes after Inflexible limped away, Irresistible also struck a mine. Both engine rooms quickly flooded, leaving the ship without propulsion. The captain, not knowing what had hit his ship, ran up a green flag on his starboard yardarm, indicating that he thought his ship had been torpedoed on that side. Irresistible was on the extreme right of Line C, close to the Asian shore; as she drifted closer, Turkish gunners enthusiastically blasted her with shells. De Robeck promptly sent the destroyer Wear, which gathered more than 600 men of Irresistible’s crew, including eighteen dead and wounded, onto her narrow deck.

At this point, with Bouvet sunk, Inflexible creeping toward Tenedos, and Irresistible drifting without a crew toward the Asian shore, de Robeck decided to break off action for the day. He was appalled by what was happening to his ships, the more so as he did not know the cause. The area in which they had been operating had been swept for mines before the operation began, and just the day before, a seaplane, flying over, had reported that the water was clear. This report seemed reliable because tests near Tenedos had shown that aircraft could see mines moored as far down as eighteen feet below the surface of the clear Aegean water. What, then, was responsible? Someone on Queen Elizabeth suggested that perhaps the Turks were releasing mines at the Narrows and floating them down on the current.

As the fleet withdrew, Keyes was instructed to take Wear and, with the aid of the battleships Ocean and Swiftsure, attempt the salvage of Irresistible. As Keyes approached, the old ship was out of the main current, still drifting slowly toward shore. Determined to save her, he signaled Ocean, “The admiral directs you to take Irresistible in tow.” The captain of Ocean replied that the water was too shallow for his ship to come in that close. Keyes then ordered the captain of Wear to ready two torpedoes to sink the derelict ship before she could go ashore and fall into Turkish hands. Before firing, however, he wanted to make certain that the water was, in fact, too shallow for Ocean to attempt a tow. Accordingly, Wear ran straight into enemy fire to take soundings. The destroyer was not hit and Keyes was able to signal Ocean that for half a mile inshore of Irresistible there was ninety feet of water. Ocean, steaming back and forth, “blazing away at the shore forts . . . to no purpose,” did not respond to Keyes’s repeated order to take the crippled ship in tow. Keyes then signaled Ocean: “If you do not propose to take Irresistible in tow, the admiral wishes you to withdraw.”

Meanwhile, the situation aboard Irresistible had stabilized. She was down by the stern, but no lower in the water than she had been an hour before. Keyes decided that she would neither sink nor drift ashore for some time and that he would return to de Robeck and suggest that trawlers come in after dark to tow her back into the main current, which might then carry her out of the Straits. As he was leaving, he approached Ocean in order to repeat his order for her to withdraw. At just that moment, 6:05 p.m., Ocean hit a mine. There was a violent explosion and the old battleship listed to starboard. At almost the same moment, a shell hit her steering gear and she began to turn in circles. As Turkish gunners now pounded this second helpless target, destroyers raced in to remove her crew.

Bringing details of these disasters, Keyes returned to de Robeck in Queen Elizabeth outside the Straits. Following his report, he proposed that he go back and torpedo both of the abandoned battleships, Irresistible and Ocean. De Robeck gave permission and Keyes returned in the destroyer Jed. Creeping into every bay, he found nothing. Now believing that both battleships were at the bottom of the sea, Keyes went back to the flagship, where he found Admiral de Robeck enormously depressed. The day, said the admiral, had been a disaster: Bouvet was lost, Gaulois was beached, Suffren’s injuries were so great she had to go into dry dock; of the French squadron, only Charlemagne remained capable of further action. In addition, Irresistible and Ocean were gone and Inflexible, counted on to engage Goeben, needed to go to Malta for extensive repair. De Robeck was sure, he said to Keyes, that having suffered three battleships sunk and three more put out of action, he would be dismissed the following day. Keyes, who had more experience of the First Lord than de Robeck did, replied that Churchill would not be discouraged; that, instead, he would respond by sending reinforcements. Apart from the 639 men lost in Bouvet, casualties had been moderate: sixty-one men in the entire fleet. The three lost battleships had been due for the scrapheap, and, even with three more out of action, the fleet remained powerful. De Robeck’s spirits rose and he and Keyes discussed how to deal with the minefields. The civilian trawler crews would return to England to be replaced by regular navy seamen from the lost battleships. Sweeping apparatus would be installed on destroyers. And then, when everything was ready, the navy would attack again. On this optimistic note, the admiral and his Chief of Staff ended the long day and night. Later, Keyes would write of his thoughts that night: “Except for the searchlights, there, seemed to be no sign of life [inside the Dardanelles]. I had a most indelible impression that we were in the presence of a beaten foe. I thought he was beaten at 2 p.m. I knew he was beaten at 4 p.m.—and at midnight I knew with still greater certainty that he was absolutely beaten. It only remained for us to organize a proper sweeping force and devise some means of dealing with the drifting mines to reap the fruits of our efforts. I felt that the guns of the forts and batteries and the concealed howitzers and mobile field guns were no longer a menace.” De Robeck was bolstered by Keyes’s optimism. “We are all getting ready for another go and are not in the least beaten or down-hearted,” he declared the next day to General Sir Ian Hamilton, who had just arrived from London.

On the night of March 18, Chanak, in peacetime a busy commercial town of 16,000 at the Narrows, was deserted; buildings were burning, the streets were filled with rubble, the forts were pitted by huge craters. But the bombardment had put only eight big guns permanently out of action, and the Turks and Germans had suffered only 118 men killed and wounded. The explanation was that when the shellfire became intense, the artillerymen simply left their guns and retreated into earth shelters. Nevertheless, the attack had compelled the Turkish and German gunners to fire more than half of their ammunition. At 4:00 p.m. the Chanak wireless station reported that ammunition at the Hamidieh fort, the defense’s strongest point, was running out. When the Allied ships withdrew, the Turkish heavy guns were left with only twenty-seven long-range high-explosive shells—seventeen at Fort Hamidieh, ten at Kilid Bahr. The howitzers protecting the minefields had fired half of their supply. What was to happen when the battle was renewed? Once the big guns exhausted the ammunition on hand, it would be simply a question of how long the howitzer batteries could keep the minesweepers away from the minefields; some thought one day, others two. Thereafter, in a matter of hours, the minesweepers would sweep a channel through to the Narrows. And beyond the Narrows, there was no defense.

One last hope remained: Goeben. The battle cruiser’s hull had two large holes—now temporarily plugged—caused by Russian mines struck off the Bosporus. She was ordered to raise steam; if the Allied ships broke through, she was to fight to the death. At 5:00 p.m. on March 18, she sailed past the Golden Horn and the Sultan’s palace, headed west toward the Dardanelles. At 6:00 p.m., a signal came that the Allied fleet was withdrawing. Through the night, Goeben lay in the Sea of Marmara, awaiting the renewal of the Allied attack the following day.

Meanwhile, in Constantinople, the government and the populace were convinced that the Allied fleet would break through. All Turks respected the near legendary power of the British navy; no one believed that a collection of ancient forts and guns at the Dardanelles could bar its way. Accordingly, word of the massive bombardment precipitated an exodus from the capital. The state archives were evacuated and hidden; the banks were emptied of gold; many affluent Turks already had sent their families away. The distance from Gallipoli to Constantinople was only 150 miles; most Turks expected that less than twelve hours after they entered the Sea of Marmara, British battleships would arrive off the Golden Horn.

The German and Turkish artillerymen at the Dardanelles were certain that the Allies would resume their attack in the morning. Through the night, they worked, determined to fight as long as they had ammunition. At dawn on March 19, the men were standing by their guns. When there was no sign of enemy ships, they presumed that the cause was the bad weather that had come up in the night. On the afternoon of March 19, Goeben was ordered to return to her base near Constantinople. Then, as the bad weather subsided, and day followed day without a sign of the Allied fleet, the defenders began to understand that they had won. They could not know, of course, of the terrible worries that had afflicted the Allied commanders because of the unexplained loss of Bouvet, Irresistible, and Ocean. The cause—as Admiral de Robeck did not know until after the war—was a single brilliant exploit: in darkness on the night of March 8, a Turkish mine expert, Lieutenant Colonel Geehl, had taken a small steamer, Nousret, down the Straits. Near the Asian shore, he had secretly laid a new line of twenty mines, 100 to 150 yards apart, perpendicular to the ten lines already stretching across the Straits. During the days before the massive attack of March 18, British trawler crews had never discovered these mines, nor had British airplanes spotted them from the air. For ten days, they had waited beneath the surface of the blue-green water.

After three hours’ sleep, Roger Keyes arose on the morning of March 19 and, as he often did in times of stress, shaved with a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If” propped in front of him. *42 He knew nothing of the plight of the gunners at the Narrows, nor of the preparations made by the Turkish government to abandon Constantinople, yet he sensed that victory was near. Even so, it was clear that the attack could not be resumed for a day or two. A strong wind was blowing, which meant heavy seas, lowered visibility, and poor gunnery. But Keyes had no thought—nor was there any thought at the Admiralty or anywhere in the Dardanelles fleet—of not continuing. A message from the Admiralty urged de Robeck to attack again. Reinforcements would be sent; the old battleships Queen and Implacable were already on their way; London and Prince of Wales would follow soon; the French admiralty was sending the battleship Henri IV to replace the lost Bouvet. A meeting of the Cabinet War Council on March 19 authorized de Robeck to “continue the naval operations against the Dardanelles if he thought fit.” Keyes began organizing and equipping a new minesweeping force. On March 20, two days after the attack, de Robeck reported to the Admiralty that fifty British and twelve French minesweepers, manned by volunteers from the lost battleships, would soon be available. He hoped, he said, “to be in a position to commence operations in three or four days.”

It was not to be; March 18 marked both the climax and the termination of the purely naval assault on the Dardanelles. Thereafter, as the days passed and the anchored fleet was buffeted by high winds and driving rain, de Robeck resumed his brooding. Writing to Wemyss, he referred to the attack as “a disaster.” Not only had he lost a third of his battleships, he still had no idea how this catastrophe had happened and how to prevent it from happening again. He had learned that naval guns had a much easier time dealing with ancient forts of heavy masonry than with temporary field works. He now knew that, to be fully effective, the fire of long-range guns must be accurately targeted by officers who can observe the locations and effect of bursting shells. Above all, he had learned that in restricted waters, mines protected by artillery that can intimidate minesweeping constitute a formidable defense against a fleet. But it was the loss of battleships that troubled him most. It did no good for Keyes to remind him that the battleships were old and on their way to the scrap heap. Battleships were the backbone of the Royal Navy; battleships were filled with brave men; and he, John de Robeck, had lost three. And he had no way of knowing that, if he attacked again, he would not lose another three.

On March 22, a group of senior Allied commanders gathered on board the Queen Elizabeth to confer about the next step. The moment the conference began, Admiral de Robeck dramatically announced that the fleet could not force the Dardanelles on its own. At this, one of the figures seated at the table nodded. General Sir Ian Hamilton, sent out by Kitchener to command the growing ground force assigned to “reap the fruits” of the navy’s success, agreed with the admiral. Hamilton had arrived at the Dardanelles on March 17, just in time to witness the fleet’s massive March 18 attack on the Narrows forts. He had been impressed by the mighty cannonade, but he had also seen Inflexible creeping away, her bridge burned out, her foretop destroyed, her bow low in the water. He had seen destroyers with decks crowded with hundreds of men from sunken or abandoned battleships. To Hamilton, it was clear that the Turkish guns, particularly the concealed howitzer batteries that were preventing British trawlers from sweeping mines, could not be completely destroyed or suppressed by naval gunfire. This, he believed, would have to be done by troops on the ground. On March 19, the day after the naval assault, he had signaled Kitchener: “I am being most reluctantly driven to the conclusion that the Straits are not likely to be forced by battleships as at one time seemed probable and that if my troops are to take part, it will not take the subsidiary form anticipated. The Army’s part will be more than mere landing parties to destroy the forts; it must be a deliberate and progressive military operation carried out at full strength, so as to open a passage for the navy.” Kitchener, who ten weeks before had adamantly opposed all ground operations at the Dardanelles, now replied to Hamilton, “You know my view that the Dardanelles passage must be forced, and that if large military operations on the Gallipoli peninsula by your troops are necessary to clear the way, those operations must be undertaken . . . and must be carried through.”

This exchange of messages was on Hamilton’s mind as he listened to de Robeck on Queen Elizabeth. Hamilton liked de Robeck, whom he described as “a fine-looking man with great charm of manner,” and he understood the admiral’s concern. Suppose the fleet, followed by the army’s troopships, managed to get through the Dardanelles with the loss of another old battleship or two. With the Turks still holding both sides of the Straits, how long could the fleet remain isolated in the Sea of Marmara starved of coal and ammunition? What would happen to Hamilton’s troopships and the thousands of men on board if their supply lines ran through a narrow strait dominated by enemy guns? And what about Goeben? With Inflexible damaged, de Robeck would have only the old battleships, none of which were fast enough to catch the German battle cruiser. Queen Elizabeth might do it, but how likely was it that the Admiralty would permit the prize superdreadnought to be exposed to the dangers involved in entering the Sea of Marmara?

Originally, Hamilton had hoped that the army would not have to land on Gallipoli and that a purely naval offensive could achieve the Allied objectives. “Constantinople must surrender within a few hours of our battleships entering the Marmara,” he had written in his diary, “when her rail and sea communications were cut and a rain of shell fell upon the penned-up populace from de Robeck’s terrific batteries. Given a good wind, that nest of iniquity would go up like Sodom and Gomorrah in a winding sheet of flame.” But now the admiral had said that this prospect was an illusion: that his battleships could not go through without help. And de Robeck, for his part, now grasped that Hamilton had come with Kitchener’s blessing to provide exactly that kind of help. The two men understood each other and no further dis-cussion was needed. Unanimously, the conference on the Queen Elizabeth resolved that the naval attack should be postponed. Nothing more was to be done by the fleet until the army that Hamilton was to command was ready to act. Because the troops and their equipment were scattered across the eastern Mediterranean, they must be assembled and organized to force an opposed amphibious landing against an entrenched enemy. The general estimated that he would need about three weeks.

Keyes, busy reorganizing the minesweeping force, was absent from this March 22 meeting. When he returned to Queen Elizabeth and heard what had been decided, he was dismayed. “I lost no time in having it out with the admiral,” he said later. He pleaded with de Robeck not to wait; the new minesweepers would be ready on April 3 or 4; they would sweep the mines and then the fleet was bound to get through. To wait for the army to return meant giving the Turks time to rebuild their defenses and bring in fresh troops and ammunition. But de Robeck’s mind was made up: he would wait for Hamilton and the army; the navy would act in a supporting role. Nineteen years later, in 1934, Keyes, then an Admiral of the Fleet, wrote: “I wish to place on record that I had no doubt then, and have none now—and nothing will ever shake my opinion—that from the 4th of April onwards the fleet could have forced the Straits and, with losses trifling in comparison to those the army suffered, could have entered the Marmara. . . . This operation . . . would have led immediately to a victory decisive upon the whole course of the war.”

On March 23, the day after the Queen Elizabeth conference, de Robeck broke the news to the Admiralty that he was abandoning the purely naval campaign. He proposed now to wait until April 14, when, Hamilton had told him, the army would be ready; then, together, they would conduct a combined assault against the Straits and the Gallipoli peninsula. “It appears better,” de Robeck wrote, “to prepare a decisive effort about the middle of April rather than risk a great deal for what may possibly be only a partial solution.” In a further signal on March 26, he added, “I do not hold the check on the 18th to be decisive, but having met General Hamilton . . . I consider a combined operation essential to obtain great results and object of campaign. . . . To attack the Narrows now with fleet would be a mistake, as it would jeopardize the execution of a better and bigger scheme.”

At the Admiralty, Churchill read this telegram with “consternation.” He had “regarded . . . [March 18] as only the first of several days’ fighting. It never occurred to me for a moment that we should not go on within the limits of what we had decided to risk, until we had reached a decision one way or another. . . . I feared the perils of the long delay. . . . The mere process of landing an army after giving the enemy at least three more weeks’ additional notice seemed to me a most terrible and formidable hazard.” Immediately, the First Lord drafted a message to de Robeck, overruling the decision of the conference on Queen Elizabeth and commanding de Robeck “to renew the attack begun on March 18 at the first opportunity.” Then, summoning Fisher and the Admiralty War Group to his room, he showed them de Robeck’s telegram and his own reply and asked their approval. He met “insuperable resistance. . . . For the first time since the war began, high words were used around the octagonal table,” Churchill wrote later. In the opinion of Fisher, Wilson, and Jackson, de Robeck’s message had transformed the situation at the Dardanelles. They had been willing, they told the First Lord, to support an attack by the navy alone, “because it was supported and recommended by the commander on the spot.” But now de Robeck had decided on something different: a joint operation by the navy and the army. De Robeck was the officer responsible; he knew the situation; to insist that he set aside his own professional judgment must not be done. Indeed, Fisher was overjoyed that at last the operation was assuming the form that he had always preferred. “What more could we want?” he asked. “The army was going to do it. They ought to have done it all along.” All morning, Churchill “pressed to the very utmost the need to renew the attack. . . . I could make no headway. Nothing I could do could overcome the admirals now that they had dug their toes in.” As a last resort, Churchill took the draft of his telegram to Asquith. The prime minister declared that in principle he agreed with the First Lord, but that he would not overturn the professional advice of many admirals.

At a Cabinet meeting that afternoon, Churchill announced “with grief . . . the refusal of the admiral and the Admiralty to continue the naval attack.” At that point, Churchill well understood, the Cabinet’s reaction might be to withdraw from the entire Dardanelles enterprise. The attack had failed and, as Kitchener had said in an earlier deliberation, “We could always withdraw if things did not go well.” So far, “we had lost fewer men killed and wounded than were often incurred in a trench raid on the Western Front and no vessel of the slightest value had been sunk.” But Kitchener spoke up immediately. “Confident, commanding, magnanimous . . . he assumed the burden and declared he would carry the operations through by military force.” As usual, once the war lord had spoken, there was nothing more to be said. Churchill gave up and sent a message to de Robeck telling him that his new plans had been approved. Thus it was that the decision to call off the naval attack on the Dardanelles and to initiate a land campaign was made, not by a formal decision of the Cabinet or the War Council, not by the Admiralty or the War Office, but by de Robeck and Hamilton meeting one morning in the wardroom of a battleship 2,000 miles away. Thereafter, all major decisions in the campaign were made by Kitchener and Hamilton; de Robeck’s role became the providing of naval gunfire support and other services when requested. The War Council, having approved the decision and the arrangements made on the battleship, never altered them, because the War Council did not meet again until May 19, eight weeks later. By then, 70,000 Allied troops were ashore at Gallipoli and a new British government, a new First Sea Lord, and a new First Lord of the Admiralty were in office.

No one can know whether, if the Allied fleet had tried again, the ships would have broken through to the Sea of Marmara. If so, what might have happened? After the war, Henry Morgenthau declared that the appearance of an Allied fleet off Constantinople in March 1915 would have toppled the Turkish government and driven that nation out of the war. “The whole Ottoman state, on that eighteenth day of March when the Allied fleet abandoned the attack, was on the brink of dissolution,” Morgenthau wrote. At Constantinople, “the populace, far from opposing the arrival of the Allied fleet, would have welcomed it with joy . . . for this would emancipate them from the hated Germans, bring about peace and end their miseries. . . . Talaat [the grand vizier] had loaded two automobiles with extra tires, gasoline, and all other essentials of a protracted journey. . . . [He] stationed these automobiles on the Asiatic side of the city with chauffeurs constantly at hand. . . . But the great Allied armada never returned.”

The first chapters of the new epic were completed. The days went by and silence settled over the Dardanelles. The weather constantly changed; mornings of warm, mirror-surface calm gave way to high winds, driving rain, storm-tossed waves, and sometimes flurries of snow. Not until the end of April, when scarlet poppies covered the fields of Gallipoli, did the tale resume its grim unfolding a few miles distant from the site of ancient Troy.