Runaway

The next morning, Little Turtle and his father, Sitting Bear, went out on one of the platforms at the edge of the river and hauled nets full of glistening salmon from the water. Little Turtle’s mother cleaned the salmon by cutting out their insides and stripping off the scales. She set them to dry on racks in the sun.

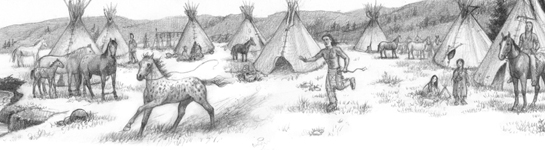

When evening came, the tribes feasted and played games together. Little Turtle led me over to watch the races. The winners took home many prizes: beaded jewelry, cedarwood bows, buffalo overcoats, even the horses of losing riders.

A man on a fiery pinto stallion was winning everything in sight. When a new rider came forward to challenge him, the man laughed and the stallion tossed his foaming head as if he were laughing, too. Although he was steaming and lathered from his many races, the stallion swept past every competitor until there were none left undefeated.

Then, to my surprise, the man jumped off his horse and came over to where Little Turtle and I were standing. “A fine-looking colt,” he said. He looked me up and down. “Sturdy legs, tough feet, a well-formed neck and head.”

Little Turtle nodded his thanks.

“His coat is striking,” the man continued. “Like snow dappled on golden earth. What do you want for him?”

Before Little Turtle could answer, Sitting Bear came over. He and his favorite stallion, Fire Tail, had just lost a race to the stranger. Sitting Bear was still breathing heavily from the race, and Fire Tail was lathered with sweat.

“What business do you have with my son, White Eagle?” Sitting Bear said. His tone was polite, but I could hear a trace of resentment beneath. He had just lost one of his good mares in the race. On the other side of the campsite, I could see White Eagle’s children fussing over the blue roan mare we had called Dream Seeker.

“I was wondering if that colt he’s holding is for trade,” White Eagle said.

“What are you offering?” said Sitting Bear.

Although I could not understand their words, I could tell from their gazes that they were discussing me. I pawed the ground lightly and arched my neck.

White Eagle brought forward some of the spoils he had won that day: a finely carved bow and arrow set, some woven sacks of food, and a deerskin shirt decorated with colorful glass beads, porcupine quills, and feathers.

From the glint in Sitting Bear’s eye, I knew White Eagle had just made a good offer. Sitting Bear was a fair man, but he did not get attached to his horses. I still remembered the first lonely nights after my dam had been traded away.

Sitting Bear’s eyes seemed to reflect the shine of the glass beads. Little Turtle looked anxious. Was I about to be traded away from him for the price of some supplies and a pretty shirt?

Sitting Bear looked to White Eagle, to the offering, and then to his wide-eyed son. “That is a very generous offer for an unbroken colt,” he said finally. “But this is Little Turtle’s horse, and it is his decision whether to accept the trade.”

Little Turtle put a possessive hand on my neck. “Golden Sun is not for sale,” he said.

White Eagle nodded, looking disappointed, and gathered his things. I breathed a sigh of relief and lowered my head.

Sitting Bear glanced at his son. “That would have been a fine trade for a decorated warhorse, much less a weanling colt,” he said.

“Golden Sun is my friend,” Little Turtle replied. “I could not place a value on him.”

Sitting Bear showed little expression as he led his tired horse away to the river for a drink. I could not tell if he was pleased or angry. Little Turtle turned to me, his face showing relief also.

He began to work with me, as he often did in his spare moments, teaching me to accept touch and to respond to the cues of his voice and body. Little Turtle ran his hands across my face, my ears, my flanks, and my belly. His light touch sometimes felt like a fly landing on me, but I had learned not to stamp my hooves and twitch his hand from my skin.

Little Turtle squeezed my leg just above the knee, over the hard chestnut, to make me lift my hoof. I felt unbalanced with only three feet on the ground. I tried to pull my hoof away, but Little Turtle held it steady until I relaxed.

Little Turtle began trimming my hoof with his obsidian knife. It didn’t hurt, but I disliked the feeling of the knife scraping against the hard sole of my foot. Still, I knew I would be able to run more freely when my hooves were trimmed.

As we worked, Little Turtle’s friend Pale Moon came over to watch. Little Turtle took his training cloth from his belt. I knew that when he had the piece of soft leather in his hand, it was time for me to pay attention. He held the cloth loosely by his side and began to walk away with swinging strides, gazing off into the distance. He looked like he was going somewhere interesting, so I began to follow him.

Little Turtle stopped and turned to me. His shoulders squared and his eyes looked directly into mine. The training cloth was clenched in his closed fist. I stopped in my tracks.

“Tawts, Golden Sun,” said Little Turtle in a praising voice. He softened his body and allowed me to walk over to him. I stopped a few paces away, waiting for his next command.

Just then a group of children came over, carrying wooden sticks and a leather ball. They were inviting Little Turtle to join their game. Little Turtle ran to get Pale Moon, and they went off eagerly with the strange children, leaving me hobbled at the campsite. I stamped my hind legs irritably, annoyed at being left behind.

As I stood there feeling sorry for myself, a commotion across the river caught my eye. A slender spotted filly was running loose among the tents, the rein of her bridle trailing on the ground. Many people had abandoned their work to catch her, but she dodged quick as a swallow around their outstretched hands.

I tossed my head and bounced up and down on my hind legs, wishing I could run with her. But the hobbles held me fast. I could only watch as the filly dodged among the campfires and children’s toys scattered in the grass.

Then a harsh voice rang out across the valley. “Get back here, you cowardly horse!” A man in dirty buckskin leggings decorated with tattered crow feathers was striding toward her. The filly swerved and bolted in a panic toward the riverbank, away from the sound.

As the man drew closer, the filly champed her teeth nervously and backed toward the water. She squealed and reared as she felt the cold spray behind her. The man was almost close enough to touch her now. I noticed that he held a braided quirt in one hand. The muscles in his arm bulged as though he was planning to use it.

The filly stepped back onto one of the wooden platforms over the river. The poles were sturdy, but they were not meant to hold a horse and they groaned under the weight. The filly shuddered, and the man stepped forward.

This was the end, then. There was no way she could avoid capture.

But I was wrong. As the man reached out a rough hand toward her bridle, the filly turned and plunged off the edge of the platform into the swirling water.