Two Healers

Little Turtle rode me down the face of the mountain until we reached the path we had taken from the Nimi’ipuu camp. I headed eagerly toward home, looking forward to food and safety and rest. But Little Turtle reined me in the other direction.

“We can’t go home yet, Golden Sun,” he said, laying a hand on my neck. “I know Wise Elm’s medicine stores like the back of my hand, and he does not have any kouse root. We will have to find some ourselves.”

I didn’t understand his words, but I realized our journey was not yet over. I pushed thoughts of golden maize and dried berries out of my mind as Little Turtle urged me forward and began to guide me along a steep ridge. Small stones showered down the face of a rocky cliff below. I could see the bones of a less fortunate animal, who had fallen or been chased over the edge. Although I was very tired, I paid close attention to where I set my hooves; one misstep would be our last.

Several times a quick shift in Little Turtle’s weight alerted me that I was getting too close to the edge. Without my rider, I would have probably stumbled in my fatigue and gone tumbling over the cliff.

The sun was high above us when we reached a clearing where the ground leveled off a little. A stream trickled away down the rocky slope. I recognized the place from our travels with Wise Elm.

A stand of kouse plants normally grew here. In the summertime they were tall flowers with bright yellow blossoms, but all the plants had withered and turned brown in the cold. It was impossible to tell one from another. The precious kouse root could be buried anywhere in the stony soil.

Little Turtle got down on his hands and knees and began to dig. I lowered my head and sniffed the dried-up vegetation. My senses were keener than Little Turtle’s, but all I smelled was dirt.

I scraped my hoof along the ground in frustration. If Little Turtle could not find the kouse, what good would his wyakin’s advice be? As I continued to paw the dirt, my hoof struck a root. I smelled something sharp and bitter, like wild parsley.

I knew the scent of kouse root! I continued to paw until the pale wrinkled root was exposed. I whinnied to Little Turtle, who hurried over to where I stood.

“You’ve found it, Golden Sun!” he cried. He bent down and cut a large piece from the root with his obsidian knife. He brushed off the dirt and put the root in his medicine bag. Then he sprang up onto my back again.

I traveled along the treacherous ridge as quickly as I dared. When we reached the valley floor, I broke into a gallop.

We arrived at the Nimi’ipuu camp by sunset. Little Turtle jumped off my back, leaving my rein trailing on the ground. He called out for Wise Elm, and the old healer emerged from one of the lodges. His face was creased where it must have been resting against a folded blanket.

“I am glad to see you return safely, Little Turtle,” said Wise Elm. “But I’m afraid Pale Moon is no better. I have quieted her cough a little with licorice tea, but this has done nothing to cure her sickness.”

“My wyakin has guided me to a remedy for her,” said Little Turtle, taking the root from his medicine bag.

“Kouse root,” murmured Wise Elm. “It works well for a certain type of cough, one that often comes from tribes who have had contact with white men. I did not think Pale Moon had this illness, but perhaps I was mistaken.”

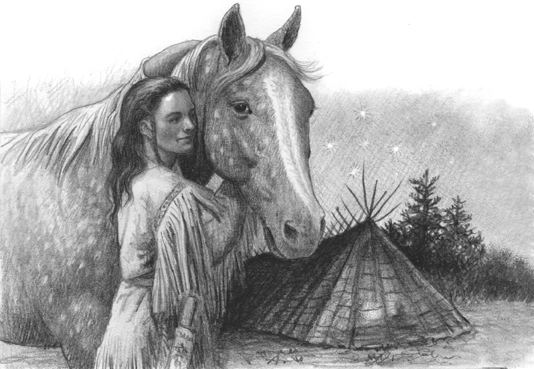

Little Turtle crushed the kouse root while Pale Moon’s mother brought her into the sweat lodge. Dancing Feather came and stood beside me. I told her of the cold nights on the mountain and of the snake’s message for Little Turtle. I did not tell her that the snake had also called me a healer. I had only found the root by accident, after all.

Little Turtle finished preparing the medicine. “Pour hot water over this and let her breathe the steam,” he said, handing Pale Moon’s mother the crushed kouse root on a cloth.

Pale Moon remained in the sweat lodge overnight. My bones shook with the pounding of drums as Little Turtle’s voice rose and fell in the ceremonial chants. Even over these rhythmic sounds, I could hear Pale Moon’s ragged coughing.

I could not help but notice how Dancing Feather flinched every time she heard Pale Moon cough. I had begun to doubt it would ever happen, but I knew now that Dancing Feather had come to love Pale Moon as I loved Little Turtle.

Pale Moon’s cough faded for a moment, and Dancing Feather closed her eyes and let her head droop toward the ground. She jerked awake as her rider suddenly choked again and gasped for breath. I nibbled Dancing Feather’s shoulder gently in reassurance.

The chanting went on and on as the stars came out and glittered coldly above. The light cast by the campfire made the world seem full of living shadows. A shiver ran through me, although I felt warm and safe.

Finally the drums stopped. Silence.

Dancing Feather had been dozing, but when the noise stopped she started awake. She looked at me with wide eyes.

Do you hear that? she said.

I hear nothing, I replied.

Yes, exactly, she said. Pale Moon isn’t coughing!

A few minutes later, Little Turtle emerged from the lodge. He looked weary. Dancing Feather and I went over to him and blew affectionate breaths across his body. He paused to stroke us for a moment before walking over to Pale Moon’s mother and father, who waited anxiously nearby.

“Her fever has broken,” he said, “and the sickness is gone. Give her some of the kouse root in hot water whenever she is thirsty. Her throat is still raw and sore, so if she begins to cough give her elderberry syrup dissolved in honey.”

“Thank you, Little Turtle,” said Red Cloud hoarsely. He looked at the boy with concern. “I know you have had no food or sleep since you journeyed to the mountain three days ago. Eat this, and then get some rest.”

He handed Little Turtle a piece of salmon pemmican. My rider gulped it down gratefully, but instead of retreating to his tepee he came back to me. He wrapped his arms around my neck and leaned his head against me.

I normally slept standing, but my legs and back ached from our trek in the mountains and the long vigil, so I dropped to my knees and lay curled on my side to sleep. Little Turtle wrapped his buffalo robe snugly around him and lay down beside me, using my body as a pillow. Though the wind blew cold that night, we were warm together as we slept under the stars.

Pale Moon was nearly well again by the time of the Winter Spirit Dance. I had learned from River Rock that this was a ceremony where everyone gathered in the lodges to speak of their vision quests.

I imagined Little Turtle telling the story of the snake who came to us on the mountain. Maybe he would also tell of how I stayed with him through the long days and nights, how I never left his side in the wind and the cold. I did not know the words they were chanting in the lodge, but I felt the music in my bones and I understood that humans and snakes and horses could sometimes speak to each other despite their different languages.

One afternoon in early spring, Pale Moon sat stirring a basket of dried elderberries mixed with water and honey, cooking them over a hot stone she had taken from the fire. River Rock said it was medicine to ease away the last of her cough, but it smelled like a treat to me.

Do you think if we wandered close and looked very hungry, Pale Moon would give us a taste of those berries? said Dancing Feather. Long gone was the frightened filly who had refused to take food from a human hand.

Dancing Feather nosed her way toward the cooking basket, stepping carefully around a group of children playing with their stick horses near the fire. Pale Moon drizzled a little of the hot berry syrup onto a flat rock for Dancing Feather. She licked it eagerly.

“Do you think you’ll be well enough to ride soon?” asked Little Turtle, coming over to the fire.

“I think so,” Pale Moon replied. “My cough is much better. I guess there was a reason for you seeing snakes all year—it turns out they had something to tell you.”

Little Turtle laughed. “At the time, I only thought I had bad luck.”

Pale Moon’s expression turned serious. “I really thought I might die from my sickness. You were very brave to go up onto that cold mountain and ask your wyakin for help.”

Little Turtle shrugged modestly. “Well, I had Golden Sun,” he said. “The nights were much less dark with a friend to keep me company.”

Pale Moon smiled. “Yes, that is the way of things,” she said.

Dancing Feather was still nosing around the fire looking for spilled syrup, and some of Pale Moon’s little cousins came over to beg for a taste of the sweetened berries. Dancing Feather stood quietly while the children toddled around her hooves, stroking her legs and reaching up to pat her nose.

Now everyone knew that Dancing Feather would not kick the children or bite the camp dogs. She had earned back every bit of the trust she had broken, and I felt that some of the wounds less visible than those scarring her flanks had finally healed.

The next morning, Little Turtle and Pale Moon awoke before sunrise to take us for a ride. A robin trilled as we walked through the milky half-light of dawn. Soon the world would be green and alive again. Beside me, Dancing Feather pranced lightly and arched her neck, proud to carry Pale Moon once more.

I felt a glow of pride, too, as I remembered the snake’s message on the mountain. I liked to think that my guidance and friendship had helped Dancing Feather, much like Little Turtle’s remedies helped sick members of the tribe.

Little Turtle and Pale Moon drew us to a halt by a stream and dismounted to wash their faces and hands. Droplets glittered on their cheeks as the sun rose above the mountains in the distance.

Dancing Feather and I stepped forward and drank gratefully from the rushing stream. We stood contentedly, water streaming from our muzzles, as Little Turtle and Pale Moon turned their faces to the sky to give thanks for the new day.