Leadership

Earning Respect, Improving the Community

IN A TOWN OF EIGHT HUNDRED PEOPLE, surrounded by cornfields and chicken hatcheries, and located more than a hundred miles from the nearest city, a man in his early thirties could easily become discouraged. But John Owens has lived here for only a year. He is still high on the smalltown values that drew him here as a high school social studies teacher with two young children of his own. Although the town’s population has dipped slightly in recent years, the local farm economy has been strong. The John Deere dealer just finished constructing a new building, and there is a recently opened medical clinic. Having escaped the housing bubble that put people in many parts of the country in financial jeopardy, the town’s bank is doing well. Mr. Owens says housing in the community has always been amazingly affordable. That was one of the reasons he decided to move here.

Mr. Owens acknowledges that many of the high school students he teaches will move away in search of better jobs and never return. But he says there are a surprising number of opportunities for those who stay. “The ability to network,” he says, is the key. “You move up to a large city and you decide to become a carpenter there, for example, and you really have to advertise hard because nobody knows you. People don’t know if they can trust you. They’ve never heard of you before. But in a small community, people know you and your family. If you’re respectable people, they’ll say, ‘Well, we’ll have him come and do our work for us.’ Now the reverse also happens. If you come from a family that is not so respectable, you may want to move out of town.”

This same principle of being known, networking, and being respected as a person that people can trust is central to community leadership. Mr. Owens singles out the banker in his town as an example. The banker is a man who is “involved in the community a lot.” The banker “doesn’t just sit back in his office and never talk to anybody.” Mr. Owens’s impression of the city council members is similar. Somehow they contribute to the town’s pride in itself.

Bureaucratic organizations, such as corporations and government agencies, have formal leadership structures based on a hierarchical model of authority. Someone is officially in charge and commands authority by virtue of that position. In contrast, communities operate through a mixture of formal and informal authority. Formal authority resides in elected and appointed offices, such as mayor, councillor, and town administrator. Informal authority accrues to wealthy residents, philanthropists, clergy, and residents who volunteer for important committees. Community leadership is for this reason harder to define and more difficult to evaluate than leadership in formal organizations. It is no less significant. Leadership is essential to good government and the rational planning in which communities are now expected to engage. Leadership guides the process of seeking government funding, building infrastructure, attracting business, and securing population growth or hedging against the ill effects of population decline.

Much of the literature on community leadership has emphasized formal aspects of local politics and planning. For instance, how school boards are elected as well as how they deliberate have been the focus of studies, as have inquiries into the formation of coalitions among local interest groups and political parties. Political scientists have been interested in communities as laboratories in which to study the functioning of democratic procedures. Students of social movements have examined how grassroots pressure groups shape local policies on such topics as school bonds and water fluoridation. In recent years, greater attention has been given to questions about the effects of tax abatement policies and government funding on such issues as land use, sprawl, and industrial innovation. As valuable as these studies of formal governmental processes are, they reveal little of what the average resident thinks about leadership or how these views contribute to the positive social atmosphere that communities hope to encourage.1

The critical aspect of community leadership, as Mr. Owens’s comments illustrate, is respect. Respect is the basis for the exercise of legitimate authority. For formal officeholders, it is the necessary qualification for securing votes along with attaining and retaining appointed office. Respect is equally essential for informal leadership. It is the basis on which consent is given and from which cooperation is secured. Respect is similar in popular understandings to prestige, but differs in the sense that prestige connotes an elevated status that may be the object of envy or modest misgivings, whereas respect suggests genuine appreciation, even toward someone whose status may not be especially high. For example, a person who is hardworking but poor might be respected, yet would probably not be considered a person of high prestige.

Respect is especially important as a criterion for leadership in small communities. When people know one another as well as they claim to in small towns, and often over a long period of time, respect is conferred through diffuse associations, such as a conversation here, a shared committee assignment there, and a task accomplished on some other occasion. In a national study, respondents were asked how much or how little they would admire various people in their communities. In small nonmetropolitan towns, 79 percent said “a lot” toward a “person who helps the poor,” 66 percent said this about a “person who gets things organized,” and 61 percent gave the same response for “a person who volunteers.” At the opposite end of the spectrum, 72 percent said they would “not admire” someone who was “too busy to get involved.” These percentages were significantly higher in small towns than among respondents in cities and suburbs.2

Respect earned through such varied roles as community volunteer or neighborly citizen is different than the respect a person gains by performing well in a specialized role, such as being a good surgeon or excellent teacher. It is the community through its various networks and activities that confers respect. The conferral of respect is the means by which the community, so to speak, rewards good behavior. It is for this reason that something of how communities sustain themselves can be learned by examining the bases on which respect is given. The behavior that is rewarded with respect should be behavior that contributes to the good of the community.

WHO LEADS?

In fictional portrayals of small towns, leadership is usually embodied in a colorful character who is either loved by all, such as the sheriff or a country doctor, or an object of ridicule or contempt, such as a bumbling town boss or corrupt lawyer. In real life, it is more common to imagine that town leadership rests with an elected body of town council persons or county commissioners. But townspeople themselves seldom mention these officials as the true leaders of their communities. For example, a teacher in a town of fifteen hundred says, “I would like to say members of the county commissions, city council, and board of education.” He notes that they “should be looked up to,” but doesn’t think that’s true. Residents in towns like his point instead to prominent members of their community who serve in a variety of formal and informal capacities. Leaders are known and admired because of who they are and what they do. They come in contact with the rest of the community through the functions they perform.

Even in the smallest towns leadership revolves around the activities that fulfill particular community needs. People are seldom immodest enough to nominate themselves, but they do not hesitate to identify leaders in the sector of the community they know best. For instance, Mr. Parsons, the banker in a town of six hundred, says bank officers play a crucial leadership role in his community and the neighboring towns. “They’re kind of thrown into it,” he says, “maybe because of their education or experience.” People come to him not only for loans but also for personal advice. “I’ve had a wife in here talking about her husband drinking,” he says. “Why me? I don’t want to hear this stuff. But you listen. You try to console. That’s what you have to do.” Mr. Steuben, the auctioneer, echoes this view. “You know, the bankers, people in business like that who are visible,” he says, “they are looked to as leaders, as people who are doing things the right way.” Others that people identify as leaders include prominent doctors, lawyers, and wealthy farmers or business owners. “It’s the business owners,” Ms. Clarke explains, “the financially successful ones.”

But townspeople just as often say they do not respect the richest people in their communities. “Success seems to breed more envy than it does respect,” one community leader observed. The perception is that those upper-income people “either screwed the community to get the money,” he says, “or somehow underhandedly came about their wealth from the backs of others.” That impression is evident in other communities where lower- and middle-class residents point to people who are “filthy rich,” or those who had just inherited their wealth, benefited from owning an oil well or a mine, or struck some business deal with government help and then failed to spread the wealth around. That perception extends to founding families that are known to have dominated local politics and business over the years. “Their families have been here for a very long time and they hold themselves with dignity,” a man of more recent vintage observes. “That’s what sets them apart from us ragpickers.” Even greater disdain is evident toward wealthy people who are deemed to be arrogant, such as “people who have money and show it off,” or “people who are cocky” about their wealth—those are the ones residents say are not held in high regard.

For a businessperson to be considered a leader, it is of considerable advantage to be homegrown or have other long-standing loyalties to the town. Not just any businessperson can qualify. It has to be someone who owns a local business and has been there for a long time, or at least long enough to have become involved in civic activities and perhaps have demonstrated commitment to the townspeople by keeping the business open against competition from the outside. It may be the owner of the hardware store, lumberyard, or bank, for example. In conversations, nobody is quite sure about it, but they figure people like this who live in town and have a business there care about the community’s future, and probably invest their money locally.

The contrast that worries townspeople is the store manager who simply works for a company headquartered somewhere else. “The grain elevator’s not owned locally anymore,” a farmer says in explaining why there are few respected leaders in his town. “The gas station would be the same way. It’s an outside influence. It’s a branch of another area.” As more of the local businesses are franchises of large corporations externally owned, townspeople worry about the consequences. They are happy to have the stores. And yet the managers of these stores are known to be newcomers or they are thought to be transients who will move on when better opportunities appear. At the least, these managers are thought to have mixed loyalties that might prevent them from being fully involved in the community.

This skepticism toward leaders who may move on in a year or two reflects some of the inherent distrust of newcomers that so many residents say is part of their local culture. Even though a newcomer may be planning to stay, long-term residents are suspicious of someone who tries to be a leader by importing ideas from some other place. “Some people come in and try to be leaders who have just moved here,” Mrs. Bradford notes as she describes her community of six hundred. Mr. Bradford picks up on the remark. “They just want to be in charge and kind of take over. I kind of resent those people who come in from the city and say, ‘Well, we did it this way.’ Well, why didn’t you stay there?”

It helps, too, if a business leader is known for having worked on some community improvement project. For example, a resident of a town of thirteen hundred singles out a businessperson who renovated a building on Main Street to be used as a theater as well as turned an old restaurant into a mini-mall with a coffee shop and beauty salon. She holds this businessperson in high regard. In contrast, she does not admire another business owner who campaigned against a bond issue to improve the local schools.

GAINING RESPECT

In all but the smallest towns, community leadership has become increasingly professionalized. The day-to-day business of town administration is more likely to be in the hands of a full-time salaried town manager than a part-time mayor who essentially functions as an elected volunteer. Both the town manager and mayor are more likely to shoulder responsibilities that require specialized training. A leader who at one time may have been comfortable appearing among friends and neighbors in informal garb is more likely to dress as an executive when representing the town. Appropriate training and apparel are especially needed when dealing with the growing number of issues that involve meetings with representatives from external government agencies. As one leader observes, “You have to bring more professionalism to this position. I don’t go to meetings in jeans and flip-flops. If I am going to a county meeting, I put on my suit and my heels.”

One would think that people serving their communities in professional roles, such as a school or town administrator, or a doctor or business owner, would need to do little else to gain respect. But in some ways their formal position of leadership in the community makes it harder. They have to do something in addition to their work to earn respect. Otherwise, they are likely to be viewed as arrogant or self-serving. Or as one local official put it, “People think the government workers just sit there and draw a paycheck.” The best way to avoid being perceived that way is to serve voluntarily in community organizations.

Consider Jocelyn Brown, the city administrator in a town of six thousand. She is a busy woman in her late forties who has an aging mother in a town thirty miles away who needs her care. Most mornings Mrs. Brown is at work before eight, and she is often still there until six in the evening. At least one night a week there is a community task force or town council meeting she is required to attend as part of her job. Yet she is also a member of the Rotary club, Chamber of Commerce, Parent–Teacher Association, oversight committee for a local fine arts center, and new economic development organization. About the only local organization she is not active in is her church.

Of course, much has been written about the decline of voluntary community organizations. The reasons include hectic schedules among two-career couples, residents moving to and from their communities, and people commuting longer distances to work.3 These difficulties are affecting community organizations in small towns as well as suburbs and cities, especially when declining populations make it difficult to sustain traditional organizations and when larger proportions of the remaining residents work outside the community. But small towns often have more of these organizations for their size than do larger communities. For instance, when the more than 1.5 million nonprofit associations registered with the Internal Revenue Service are classified by the population of the zip code in which they are located, there are more than 10 associations per 1,000 residents in the least populated areas, and that number declines to about 2 per 1,000 residents in the most populated areas (figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Nonprofit associations per thousand residents

This does not mean that residents in smaller communities are necessarily more active in nonprofit associations than inhabitants of larger communities. Indeed, one reason for the larger number of such organizations in smaller places is that many nonprofit organizations, such as a hospital board, parent–teacher organization, scouting troop, or veterans association, exist at the county or town level, regardless of how small or large the population may be. It does appear, though, that the greater number of nonprofit associations per capita in smaller places is one of the reasons that residents of small communities talk about the local importance of these organizations.4

Community organizations in small towns differ in emphasis from groups in larger places as well. Some of the most notable differences are evident in figure 6.2, which compares residents in small nonmetropolitan towns with residents in suburbs, taking into account differences in race and ethnicity, gender, age, and levels of education. The two kinds of organizations that are underrepresented in small towns are ethnic, racial, or nationality associations along with political clubs or organizations. The other organizations are all better represented in small towns than in suburbs. Not surprisingly, farm organizations are the most disproportionately represented in small towns, but so are labor unions and youth groups, and three of the organizations—church-affiliated groups, fraternal groups, and civic or service clubs—are traditionally the ones that have been most active in community betterment and community-wide charitable activities. Although the larger populations of suburbs have been conducive to specialized groups, it is also notable that membership in many of these is as common in small towns as in suburbs. For example, no significant differences are evident in these data between small-town residents and suburban residents in the likelihood of holding membership in environmental organizations, sports clubs, health and fitness centers, hobby or garden clubs, literary or music groups, or professional associations.5

Figure 6.2 Membership in selected organizations

A particularly important aspect of membership in civic organizations in small towns is its visibility. People in a small town know if the town administrator is present at the Rotary club meeting and involved in the fine arts council. Civic organizations help maximize that visibility. Other members see the councillor or local physician there at the regular meetings, whereas an individual act of kindness or charitable donation could go unnoticed.

The specific activities that earn respect are ones that either directly benefit the community, or indirectly show that the community is composed of decent and caring individuals. Dixie Longren, an elderly woman in a town of twenty thousand, says a man in her Sunday school class is the kind of leader everyone in her community respects. “He’s just a good old farm boy,” she chuckles, “but if I needed something, I would not hesitate to call him. I feel sure he would take care of it.” A woman in a town of nine hundred singles out “the lady who runs the dime store here” because she “does so much for this community.” She says the dime store lady makes small donations to the nursing home and the Sunday school children. A woman in another town of about the same size mentions her neighbors, a couple in their eighties, explaining that they have been involved in “every single volunteer effort and every single community organization.” A man in another small town nominated a teenager as a rising young leader in the community, explaining that the boy goes around voluntarily mowing lawns for some of the community’s elderly widows.

It is notable how often townspeople mention voluntary service even when talking about fellow citizens who hold formal leadership positions in the community. “We’ve got a couple guys here who are CEOs of the bank and other businesses,” says a resident of a town of twelve hundred, “who put a lot of time into the community. They volunteer a lot.” A councillor in a town of twenty-five hundred says respect goes to leaders who are “very generous toward the community.” Ms. Clarke shares this feeling. She says the financially successful business owners in her town are respected because they are “real givers to the community.” In another small town, one of the long-term residents offers a similar view somewhat more pointedly. “They don’t necessarily have high positions in the community, but they’re caring people. They’re genuine people.” She says the mayor is not one of them. He is regarded locally as “a bit of a scoundrel,” as someone who is not considered a caring person.

Here again it is the scale of small places that matters. “You see people every day,” is how one man puts it. “You see those little things that people do.” It helps if someone is known as the bank president or chair of the Lions club. But it is still necessary for that person to do little things, such as showing up at a picnic fund-raiser or helping an elderly person across the street. In a large community nobody would have noticed. Or if they had, they would have had nobody to tell. In a small place word spreads. In interviews, people recount stories that have circulated through the gossip mill. They have heard that someone assisted a neighbor, that another person regularly visited the sick, and so on.

The way respect works is that people who do contribute to the community feel rewarded for doing it and thus are more likely to continue being involved. As one woman explained, she really liked the respect she earned by serving on the local school board, and this appreciation was one of the reasons she ran for city council and served a term as mayor. But equally important is the fact that people who have not done much to help the community see how things work and decide to become more engaged. A good example of someone becoming more involved is a woman who says she did not grow up thinking that community service was important. “My parents didn’t focus on volunteering in the community, so I didn’t have that sense of needing to help your community.” But in the small town where she now lives things are different. “This town has taught me that community is important and you need to volunteer. There is a strong sense of needing to help each other. We have Christmas suppers and Thanksgiving dinners for those who don’t have family close. We have a lot of volunteers in our nursing homes and at the school.” She personally volunteers for a civic organization, at the school, and in her church.

Approaching Mayville, Wisconsin, from the south, a traveler on Highway 67 passes a well-kept public park on the right, two cemeteries on the left, and several large road signs. One of the signs includes the emblems of many of the town’s established community organizations. German Lutherans and Catholics, arriving in the 1860s, mostly settled Mayville. The town is surrounded by farms with fertile fields as well as large dairy herds that contribute to the state’s abundance of milk and cheese. Mayville itself is home to several tool-and-die firms that have been in business here for more than a century as well as a growing number of commuters who travel fifty miles each way to jobs in Milwaukee.

Like many small towns, in Mayville, the elected and appointed officials rely heavily on voluntary community organizations to look after the town’s many civic activities. In all, more than fifty of these are organized as formal tax-exempt associations and there are at least a dozen more that function informally. This is in a town of only slightly more than five thousand people. Many of these organizations are familiar landmarks in communities of this size. Besides the two Lutheran churches in town, there is one nearby in the countryside along with the larger Catholic Church in the center of town and the smaller Methodist Church a few blocks away. Well-established civic organizations include the Lions club that meets on Wednesday evenings at a local restaurant and the Veterans of Foreign Wars that meets at the VFW Hall the first Thursday of every month. Other traditional organizations include the Knights of Columbus, Rotary International, Kiwanis International, and the Parent–Teacher Association.

Although membership in these traditional organizations has declined nationally, newer special interest groups flourish in Mayville, as they do elsewhere. Some, like the American Bowling Congress chapter that came to Mayville in 1974, and a bikers’ group that formed in 1976, are no longer new. Others, like Women’s Aglow, an evangelical fellowship, and True Men Ministries, its male counterpart, are of more recent vintage.

And in Mayville, as in many small towns, what was once an informal alliance between voluntary organizations and local government has resulted in new forms of public–private interaction. A local chapter of the Wisconsin Association for Home and Community Education, for example, conducts leadership seminars in grant proposal writing, and Main Street Mayville seeks public funding for neighborhood development and community improvement.

Volunteering, caring for one’s neighbors, and working together on community projects are clearly of benefit to the community’s well-being. Civic involvement in these instances does not depend solely on the altruistic motives of the individuals who participate. It is encouraged by the reward system of the community itself. Civic involvement is rewarded with respect. People who contribute to the life of the community are looked up to, while those who do not are punished with a lack of respect. “It’s the people who reach out to people and treat everybody as an equal,” a councillor in a town of two hundred says. “They do things for other people, but not for recognition. They do it because there’s a need.”

Disrespect is directed especially at people who do not take care of themselves. “Oh, we have people here who don’t even keep their grass mowed,” one man observes. “You can be poor, but you don’t have to be dirty,” says another. “We have people here who just sit around and complain and don’t do anything,” a woman who describes her community of twelve hundred as a hardworking town says. People who keep too much to themselves are looked down on as well. “They’re kind of like cockroaches,” Mr. Steuben says. “You never see them, but they’re always around. This community is exactly what you make of it, I tell them. If you want to stay in your doggone house and not interact with anybody, you’re allowed to do that. But don’t turn around in a year and bitch about nothing going on in the community.” The specific attributes associated with disrespect underscore what is valued in community leaders. Disrespect inheres especially among those who are “self-centered and selfish,” as one woman puts it. It is the altruistic virtue of the community that must somehow be upheld. In the simplest terms, that means helping to make the community better and caring for its needs. In broader terms, a leader must be upstanding, someone who cares for their property, and is sociable and clean.

Civic participation elevates individuals in the eyes of fellow residents, and yet ironically, community involvement also levels the playing field, as it were, and thus eases the tension that might otherwise exist in small towns between the haves and have-nots. A woman who serves on the city council in her town of eight hundred makes a revealing comment in this regard. She says she is respected because of her position on the council, but adds, “I don’t put myself above them on a pedestal or anything like that. I just do what I was born to do.” Working alongside farmers, waitresses, and retirees cleaning up a vacant building as well as putting on a potluck dinner shows that she is just a member of the community like everyone else.

CULTURAL LEADERSHIP

Although community leadership nowadays even in the smallest towns generally implies an office worker who oversees budgets and implements planning (with voluntary civic work on the side), an important and frequently overlooked leadership role is performed by the person or persons who might aptly be called the village folklorist. Not to be confused with the academic study of folklore, the village folklorist is the keeper of local traditions, the resident who knows the town’s history, remembers what happened when, and can repeat the stories to anyone interested in listening. Sometimes the village folklorist is officially associated with the local historical society and may even be the curator of a small museum in which the community’s prized artifacts are kept. If the position were in a larger community, it might be held by a faculty member at the state or municipal university, or an employee of the metropolitan museum and cultural center. In a small town, it is likely to be a resident who has earned a reputation for storytelling, perhaps at the local hardware store or as editor of the community newspaper. It is just as commonly a person who developed a sideline interest in town lore that has become of value in preserving the community’s heritage.

I emphasize the village folklorist because the sense of community that prevails in small towns is greatly indebted to the leadership this person provides. It is wrong to imagine that residents of small towns identify with their communities only by virtue of living there. The community is also a story that people know. The narrative includes a myth of origin—usually grounded in historical fact, but generally with apocryphal elements—that says something about the town’s first inhabitants, perhaps starting with settlers of European descent or including Native Americans. The community story is likely to include the larger-than-life exploits of a hardy pioneer, early town promoter, teacher, or doctor. There may be the memory of a devastating fire or flood, or a tragedy that befell an unfortunate family.

These stories are not the shared experiences that residents know first-hand. The tales that give their community a distinct identity are known because someone has handed them down, repeated them at a town meeting, printed them in the local newspaper, and filed them away somewhere at the library or courthouse. They are the stories of the United States writ small. Nearly every small town of a few thousand residents has called on its local folklorists to put together a commemorative pamphlet describing its history or an event with the same purpose. Walk the central streets of any town, and the artifacts that have been preserved are not hard to locate—such as the mural on a business wall, a statue of a Civil War soldier, a plaque at the entrance to the town park, or the names inscribed in church windows.

Vera Gruenling is one of the more colorful village folklorists we met. She lives in a farming town that has grown over the past twenty-five years to more than twenty thousand, which means a large number of newcomers who are unfamiliar with the community’s history and traditions. Now in her seventies, Mrs. Gruenling has lived here all her life and was a teacher for nearly four decades. A typical morning finds her at the YMCA for an hour of exercise, and then tutoring fourth graders who are struggling with math and English. She knows the town’s stories by heart, having so often taught her elementary school pupils how the first settlers struggled to build houses and plow the land. She tells of the town’s founders, how they secured a railroad, and where their pictures can be found in the town’s museum. The stories are not only about rugged individualism but also about the community’s efforts to help one another and protect itself from outsiders. In the early days there were bands of gypsies who stole food; later, the community competed with neighboring towns for good highways and better stores. She recalls the flood of 1965 that wrecked the park and required the community to build a new zoo. From time to time, the editor of the local newspaper calls her for information about the town’s past. Recently, she has been participating every Wednesday in a Living History group at the senior citizens’ center. The group is recording oral histories and writing memoirs. “We ramble on about things that happened in the past,” she says, and help the community “learn more about the place.” She also volunteers at the local historical society, entering biographical information into its computerized database. The historical museum has recently opened a new wing that includes an impressive visual display of the town’s history.

Mrs. Gruenling is typical of other village folklorists we met in several respects. Being a lifelong or at least long-term resident, and being among the community’s older citizens, is a natural advantage for knowing the town’s past. Having been a teacher, shop owner, or elected official generally means a large network of local acquaintances and opportunities to have heard as well as told community lore. We talked with antique dealers, waitresses, and hairdressers who were known especially as fonts of local lore. Being retired like Mrs. Gruenling is another advantage insofar as it makes time for volunteer activities. Other amateur folklorists we talked to included residents who volunteered at the local library, school, church, or club. In the smallest towns, neighbors sometimes knew simply by reputation who to ask for the best stories or latest gossip, but volunteering at the library and other local centers of culture meant that even a stranger could benefit from the folklorists’ information.

As local government offices have expanded and become more formalized, the village folklorist in some communities is a person whose official functions require knowledge of local history and traditions. Sara Porter-field is an example. For the past decade and a half, Mrs. Porterfield has been the director of park facilities and services in a southern community of six thousand that prides itself on preserving its antebellum charm while adapting to the changing social and economic realities of the twenty-first century. Her job includes publicizing information to attract tourists as well as handling the technical details of park usage and maintenance. Having recently updated the community’s Web site, she can recite almost word for word the story of the town’s founding and its more recent developments. She knows the year the first textile mill was founded and when the last one closed, where the old shirt factory was located, which famous writer visited in the 1950s, and how the art deco movement reshaped the town square. Her repertoire includes stories about an early gristmill, an influential preacher, a large peanut farm, and how the railroad was built. Not surprisingly, she believes the community’s strength depends on knowing its past. That means that “everybody knows who you are, and who your mom and daddy were.” It also means a fall festival when the community’s history can be recalled, and shopkeepers who can tell tourists colorful stories of the town’s past. “We think that’s our niche,” she says.

In many communities, the village folklorist serves not only to instill pride in the town but also to preserve critical aspects of local ethnic culture. A leader in a predominantly Finnish community, for example, told us stories about the settler’s difficulties learning English and the ridicule Finnish children sometimes were exposed to in school. He described with some amusement the tradition of the Finnish sauna in which extended families and neighbors participated each Saturday in preparation for Sunday worship services. Non-Finnish neighbors imagined promiscuous behavior occurring and on several occasions filed lawsuits seeking injunctions against the practice, he said, but in reality the norm was to be as “pure in the sauna as in church,” where strict gender segregation prevailed. In other towns, keepers of local legends told of Germans being persecuted during World War I, Swedish ancestors settling as a colony, Spanish-speaking forebears working as migrant farm laborers, and Italian immigrants working in the mines.

Native American leaders play a particularly important role in preserving both the ethnic and village traditions of their communities. Mato Tanka lives in a town of seven hundred people on an Indian reservation composed of Oglala Sioux, some of whose ancestors were veterans of the battle at Little Big Horn and others whose relatives were at Wounded Knee.6 Fluent in Lakota and English, Mr. Tanka grew up on the reservation and dropped out of school in tenth grade, but through the insistence of his grandfather got a job immediately doing custodial work, graduated a few years later from the police academy, and eventually earned a law degree from one of the nation’s most prestigious law schools. He currently serves as the tribe’s attorney, dealing with litigation involving land and gaming regulations, and is a principal keeper of Lakota narratives, songs, and sacred rituals that extend for at least nineteen generations. In this capacity, Mr. Tanka is the head singer for the Lakota Sundance, performs at wakes and on other ceremonial occasions, and teaches classes in traditional singing. The Lakota understanding of history, he says, is not linear but rather is about who you are. “The essence of what I want to do with my life,” he stresses, “is to be a good relative.” That means especially participating in local service activities but also being related to everybody, whether through blood, in the community, or via the Lakota understanding of the grandfather great spirit.

Mr. Tanka lists the issues that come across his desk as an attorney: estate settlements, divorce, an arrest for drunkenness, someone needing financial assistance, a jurisdictional dispute with the state or federal government, or a new or cold-case murder investigation. All too often, litigation results from poor planning on the part of one or the other of the disputants. Mr. Tanka wishes more of his community understood the true meaning of Indian time. “My grandfather taught me about Indian time,” he says. “It means you buy your snow shovel in the summer.” He thinks frequently of his grandfather and his grandfather’s grandparents. They are the models of what it means to be a good relative. “They gave their lives for the people,” he explains. “I think they’re watching.”

Although they are often wise in their own right, village folklorists are not to be confused with the proverbial village oracle or sage. Folklorists are known locally for their knowledge of local affairs. They represent and convey information about the past plus present activities of the community. In contrast, the village sage speaks from personal wisdom, gained perhaps from reading or travel. A sage who writes or speaks to an external audience may acquire a reputation outside the community that becomes identified with the community. “Yes, so-and-so lives here,” community residents may say about a well-known essayist in their community. But they may also be chagrined about a self-styled sage who writes a newspaper column or Internet blog. The local folklorist is more likely to be regarded by fellow residents as a community asset.

In social science jargon, the village folklorist is a central node in a social network that produces and reproduces cultural capital. Usually cultural capital means the knowledge a person uses to get what they want, such as a high-paying job in a prestigious occupation. Because social scientists tend to think about the whole society as the relevant unit, rather than local communities, the cultural capital that matters is readily exchanged in the society-wide stratification system for money and status. An advanced degree, training in a profession, technical skills, and familiarity with haute couture are the best kinds of cultural capital to have.

But in small towns it also matters to have locally specific cultural capital. Some of what is important to know is instrumental. When resources are scarce and perhaps geographically limited as well, it matters to know who in town is best at welding together a broken trailer hitch and who to call when the septic tank overflows. Cultural capital also consists of expressive information that is good for social networking. Gossip can be exchanged for instrumental information. Knowing the town’s history and being able to tell its stories serves similarly. An insider knows the traditions or who to ask. Being an insider feels better than existing on the margins of a small community. This is why the village folklorist fulfills a valuable role.

HOLDING OFFICE

“Being the first female mayor here,” Margaret O’Brien says, when asked what goal in life she is most pleased to have accomplished. This is her ninth year, the first of her third term. “Even though we’re a small rural town, I’m proud of what it is like today, the progress we’ve made. How do I say this and not sound sexist? I’m proud that I can work with a male council, and work right up there with the males and feel comfortable.”

Mrs. O’Brien’s story is not so different from that of many elected officials in small towns. She came here as a young bride forty years ago. She had grown up in a different state, living near an air force base, and dreamed of joining the military when she was old enough. She wanted to serve her country and see the world. Her father said no. That might be fine for her brothers, but not for her or her sister. She decided to find another way to travel. She became an airline stewardess, as they were called in those days. It was fine for a while, but having to be thin, pretty, and wear a uniform with a little blue cap got old quickly. “I was just a waitress in the sky,” she recalls. Soon after, she quit, got married, moved to the community where she has spent her life, and became a mother. She begged her husband, couldn’t they move, couldn’t they go live somewhere else, anywhere? But this was his home. He had a good job with the utility company. He wanted the children to live near their grandparents. She took courses at a nearby community college and got a job as a social worker.

Over the next three decades, Mrs. O’Brien’s job as a social worker provided a steady income that supplemented her husband’s salary and made it possible to send their children away to college. Although she was still regarded as a newcomer by many of the townspeople, the job put her in contact with the local residents and gave her an opportunity to learn valuable skills. State and federal regulations governed what she could and could not do. She worked with families on welfare and in need of medical assistance, applied for grants, and interfaced with doctors and the police. She also did volunteer work. Having learned from her parents that a person should give back to her community, she tried to do just that. Being mayor is a way of continuing to serve, even though she is technically retired.

On most occasions, the daily life of a small-town mayor is not strenuous. Mrs. O’Brien sips hot water with lemon while listening to the morning news on a regional radio station and reading the only daily newspaper available in her part of the state. She exercises for a half hour on the treadmill and then heads over to city hall. This morning she interviews a candidate for a city job, and is pleased to discover that they have experience working in a similar-size town, then handles some other business and staffs the phone so her assistant can run errands. She attends a Rotary luncheon, makes some calls about a Republican caucus meeting she plans to attend in another town on Saturday, and has time by midafternoon to do a crossword puzzle and catch up on some reading. Still, there always seems to be something needing her attention. A local lake and the cemetery both need improvements. The highway that runs through town is being repaved. Grant writing still takes up much of her time. She points to new light poles and trash receptacles, and mentions a new water storage facility and recycling center—all these projects required grants from the state.

The expertise required of public officials in towns like Mrs. O’Brien’s is constantly changing. Although her grant-writing skills developed over several decades, the reading she does on slow afternoons is often concerned with new funding opportunities along with state-mandated programs. For instance, she suggested recently that the local library purchase used car seats for infants that could be loaned to low-income families, only to learn that the idea would put the town in legal jeopardy if an accident happened. In other communities of fewer than five thousand people, town administrators described master’s degrees they had earned in public administration and continuing education classes they were required to take.

But it is the intrigue of local politics that small-town officials find most interesting and especially challenging. Marvin Bencke is a longtime county commissioner in Mrs. O’Brien’s town. He is a third-generation farmer, a college graduate, and has taught school. Because of having to deal with government agricultural programs, he became interested in questions of public finance and tax policy early in his career. That prompted him to run for public office. Being a lifelong Republican, he ran on that ticket, won, and served two terms. Although he was planning to sit out the next election, a fellow commissioner died and Mr. Bencke offered to run for that seat. But the Republican Party had another candidate in mind. Mr. Bencke ran instead as a Democrat, won, and served for eighteen years on that ticket. He says it made life interesting, to say the least.

When scandal erupts, it can be especially devastating in a small community. Carol Mason, an appointed official, recalls the former mayor in her town of five thousand. When her mother died, he came to her house dressed in overalls, picked a spot in the backyard, dug a hole, and planted a tree in her mother’s memory. She thinks of him whenever she looks at the tree from her kitchen window. A few years later, she stopped at his office with some papers to sign. He said he had something to take care of first and asked if she could come back in an hour or two. When she returned, she learned that he had gone to the rural cemetery where his parents were buried and shot himself. She learned later that he had mistakenly authorized the city to purchase some property. The town council agreed it was a simple mistake, but the newspaper picked up the story and turned it into a major scandal.

Scandals aside, it is seldom easy to hold an elected or appointed office in a small town. Doing so exposes public officials to squabbles that can simmer for years. Every local official we talked to had stories to tell. In some communities, residents were angry years later because their school had undergone consolidation. In others, there were lingering disputes about the town having to rely on the county sheriff’s department for law enforcement instead of having a police force of its own. Or there was resentment because a neighboring town had a better health clinic, or faster emergency medical and rescue services.7

Mrs. Mason’s community is surrounded by coal mines. At least it was until the 1980s, when the coal mines shut down. Now the community is surrounded by abandoned pits. There used to be a manufacturing plant in town that employed a thousand workers, but that too has closed. She describes the community as a “friendly town” that takes special pride in its basketball teams. But with the economic setbacks the community has experienced, her job is not easy. It depends both on technical expertise in writing grant proposals to state and federal agencies, negotiating with environmental agencies, and utilizing informal interpersonal skills. Mrs. Mason has been instrumental in securing funding for a new hospital and bargaining with the state to locate a medium-security prison in the area. But she could lose her job at any time if she fails to maintain the approval of a majority of the deeply divided town council. She is the buffer between the council and the public. If she could wave her magic wand and ask for anything, she says she would wish for greater harmony. “People make something really big out of something that could be handled much easier,” she remarks. Small problems too often get blown out of proportion. Her constant motto is “Be careful what you say.”

Given the potential for significant misunderstandings, it is surprising that anyone runs for public office in small towns—and in some of the towns we studied, residents said it was difficult to find good leaders. But usually community pride is sufficient to override such difficulties. There were public officials like Mrs. Mason who had gone to college and graduate school, secured formal training in public administration, and returned to their hometowns because of spouses’ employment or needing to be close to parents. Others, like Mrs. O’Brien, held jobs in their communities that made it hard to say no when asked to run for elected office.

There are also public officials for whom their small towns function as a frog pond in which to cultivate aspirations for wider public service. Craig Baker holds an appointed administrative position in a foothills county of ten thousand populated mostly by farmers and ranchers. The son of a local rancher, Mr. Baker never imagined himself following in his father’s footsteps. As a teenager, his interests turned increasingly toward government. He recalls one year at the county 4-H fair being assigned to clean one of the exhibit buildings and meeting a state representative whose table was in the building. In college Mr. Baker majored in political science, volunteered for political campaigns, and seriously considered going to law school. But shortly after graduation, while working in the state capital, the position he now holds opened up. Although he was young and inexperienced, his political connections worked to his advantage. “I’m not an educated expert,” he says, but he feels he has an “instinct” for local politics. He knows the back roads and people of his county. He understands that government moves slowly here and that it takes a lot of patience to move people out of their comfort zones. His dream is someday running for the state house of representatives. Meanwhile, it gives him a great deal of satisfaction to help people in his community both on and off the job.

COMMUNITY BETTERMENT

Besides caring for one another in small ways, community leaders are expected to initiate projects that actually improve the community. In interviews with leaders and nonleaders alike, we found this expectation to be nearly universal. Residents of declining towns describe plans to make the place look better by tearing down or renovating old buildings, starting new businesses, and attracting jobs. As the mayor of one town explained, “Our Main Street isn’t what it used to be, but we keep it from looking like it’s falling apart.” Towns that are growing often have plans to maintain the small-town feeling by starting a historical museum, initiating a festival, or having a community barbeque. People admit that the community gets to looking seedy if nothing is done. They worry when the town square begins to deteriorate, trees die in the park, and vacant lots are not mowed. They speak with pride about plans to fix up an old bridge or build a new fire station. These activities have important symbolic as well as instrumental value. They are a point of central identity for the community and a visual reminder of something that residents hold in common—the courthouse, municipal building, public library, park, school, and renovated post office on Main Street.

In our interviews, we found town leaders and residents engaged in a delicate dance between tearing down decaying structures so that new ones could be built and seeking to preserve historic buildings. On the one hand, townspeople understood the significance of keeping things from looking as if they were falling apart. Just as in urban neighborhoods, broken windows and abandoned buildings signaled disorder plus seemed to invite crime.8 On the other hand, efforts were made to preserve and restore the best historic buildings. As a community leader in one of the southern towns we studied explained, her community was having success in attracting tourists who enjoyed weekend excursions to a bygone piece of vintage Americana. “We have these beautiful old homes, beautiful streets with trees, the town square, and antique shops,” she says. Urban planners had even visited to learn how to replicate the small-town feeling evident there.9

This was not an isolated example. Many of the towns we studied were attempting to promote tourism as a way to secure jobs, retain population, and increase tax revenue. Several had launched formal tourism committees. One had copyrighted the town’s name as a brand that could be printed on souvenirs. The efforts ranged from small-scale projects, such as opening an antiques mall or hosting an annual motorcross rally, to more ambitious ones, such as building a visitors’ center and historical museum to opening a casino. The smaller efforts had reasonable success in attracting visitors from the immediate vicinity as well as taking advantage of such amenities as a lake that could draw fishing and boating enthusiasts, an ethnic heritage that served as an excuse for an annual festival or crafts show, and proximity to a city, so that agrotourists could be attracted by events at local farms. The larger projects usually occurred in special locations, such as in towns adjacent to national parks or near Indian reservations. Sometimes a town benefited from having been the birthplace or childhood home of a president, or the gravesite of a famous pioneer or cowboy.

Profile: North Stonington, Connecticut

Unlike many small towns, the leaders of North Stonington, Connecticut, faced the challenge not of promoting growth but rather of controlling it. Located near Interstate 95 in the corridor between New York and Boston, North Stonington was an attractive prospect for corporate expansion and new upscale housing developments. Its population of 3,748 in 1970 grew to 4,991 in 2000, prompting concerned residents to consider steps to preserve the historic small town character and rural beauty of the community.

In 2003, a steering committee of resident volunteers produced a comprehensive Plan of Conservation and Development for the community. The plan called for preserving existing farms and attracting new agricultural businesses, improving roads, and ensuring a variety of housing choices. It also identified as high priorities the need to set aside limited areas for commercial growth, reduce the overall density of residential development, protect natural resources and open land, keep municipal and recreational facilities in their present locations, and promote energy conservation.

A follow-up evaluation six years later showed that much remained to be done but that a number of actions had been taken. New zoning regulations had been passed, a water supply and quality-management plan had been adopted, a plan to control noise pollution had been implemented, and regulations were in place for energy-generating wind facilities. There was a lengthy list of ideas still under consideration. The 2010 census showed that the population had edged up to 5,291, or an increase of 6 percent in ten years.

That was all to the good, as was the fact that numerous public meetings had been held and community spirit had been facilitated in the process. The goal of preserving a bucolic ambience, however, came increasingly into conflict with concerns about high taxes. Despite relatively high household incomes, residents incurred rising commuting expenses and some experienced layoffs. Community meetings turned increasingly toward discussions of economic development that might alleviate tax burdens or generate sufficient revenue to improve the school system.

Community spirit was evident in the fact that residents proudly celebrated North Stonington’s bicentennial, commemorated the community’s fallen heroes each Memorial Day, and happily promoted the local basketball and soccer teams. Being a community meant taking part in those activities. It also meant exchanging hard words from time to time at town meetings and voting in hotly contested elections for town leaders who held varying views of community priorities.

Residents frequently expressed ambivalence toward these touristseeking ventures. The small efforts that had limited success were usually regarded with mild amusement as something that gave the town a bit of flair and drew a few outsiders without fundamentally changing anything. The larger projects often made more of a difference and generated greater controversy. For example, in one of the towns that had become a regional gaming center, residents complained that they no longer knew one another and had to lock their doors. They conceded, however, that revenue from the casinos was paying for an improved water and sewage system, and buildings were being preserved that otherwise would have fallen into disrepair.

The key to managing residents’ ambivalence in this case was to use the new revenue not only for water and sewage projects but also to maintain the town’s historic identity. In other communities leaders expressed hope that a new county museum, a restored courthouse, renovation of an old warehouse, a small theme park, hitching posts, or traditional-looking lampposts would simultaneously attract visitors and commemorate the community’s past. In the process, it was of course not the actual past that was being preserved but instead an imagined one that selectively shaped and reframed the town’s identity.10

While community betterment projects make an actual difference to the quality of life, they also serve a symbolic role. They do this in two ways. One is by enlisting the community’s involvement in making them happen. When people have worked together on a beautification project, circulated petitions and raised funds, or even voted for a public bond offering, they renew their sense of collective ownership of the community. The other symbolic function is the tangible mark that the project bestows on the town. For example, “We have a huge new water tank up on the hill,” one resident exclaims. “It’s awesome.” For her, the water tank with the town’s name emblazoned on the side is an identifying feature. And when community betterment projects fail, the blow is symbolic as well. The same woman, for instance, laments the fact that year after year, the community’s finances and depleted school enrollment prevents it from building a new music room in the high school to replace an earlier one that was torn down after being declared structurally unstable. “Any other school would just build a new facility,” she says, “but no, not here. Money is so tight. You have to go through conniptions to get anything done.”

If tearing down old buildings and mowing vacant lots are important to a community’s sense of well-being, infrastructure and essential social services are vital. Much of the discussion in national media about infrastructure and services has focused on striking an appropriate balance through state appropriations and tax measures between rural areas and cities. But for people who actually live in small rural towns, the issue is frequently about competition with other small towns than about trade-offs between rural areas and cities. Community leaders know that there is a limited supply of state and federal funds along with a limited number of doctors, dentists, and pharmacists willing to live in small towns. So if one town lands a grant or lures a physician, another town may be at a loss not only for health care but also to attract a new business or keep residents from leaving. In some ways, this is no different than it has been for a long time. When towns began, they competed with one another to secure a railroad or become a county seat. The difference now is that health care, schools, and government services have become the principal activities subject to such competition. The other difference is that distances have shrunk. When transportation was more difficult, towns ten miles apart could compete successfully. Now the competition occurs between towns thirty or fifty miles apart.

Mr. Keller, the medical clinic director who lives in a town of five thousand, has been centrally involved in the competitive struggle for health services in small towns. In his administrative role he constantly skirmishes with the hospital, in the newspaper, and with other clinics in the area that could damage business at his clinic. The newspaper, he says, seems to dislike his clinic and favor the other one in town. He organized a women’s health fair at the local Walmart recently and the newspaper refused to publicize the event. He still fumes about that. Sometimes the competition with the other clinic is only good-natured rivalry, but at other times it becomes so intense that people refuse to speak to each other or make angry remarks.

At one level, securing health services for the community is simply a matter of writing grant proposals and lobbying with state officials. Mr. Keller says it is no different in that respect than getting a new bridge built or finding money for a new fire truck. But schmoozing matters even more. He wound up going to a lot of golf tournaments. He meets doctors, businesspeople, and faculty at medical schools and colleges at these tournaments. When he finds someone who might be interested or knows someone else who might be interested in moving to a small town, he makes his pitch.

Community leaders have also been doing more to target the young. The pitch to young people is that small towns may offer more job opportunities than someone oriented only toward cities might assume. Teaching, social work, and health services are common examples. Keeping in contact with people who leave is difficult, although community leaders say it has become easier because of email and the Internet. The idea is similar to the one used by colleges to secure donations from alumni and recruit children of alumni as students. High school reunions and homecoming festivals function in the same way in small towns. Another strategy that has had some success is economic development directors keeping in touch with their former classmates.

INNOVATION

Although the social sciences have seldom regarded small rural communities as likely venues for innovation, many of the leaders we talked with said innovation was precisely what was needed if their towns were to attract jobs and retain population. Skepticism about small-town innovation stems from theories of modernization, which associated new ideas with the industrial, technological, and scientific advances that took place in cities. Network studies have reinforced this view. If small towns are literally places in which everyone knows everyone else, it is easy to assume that residents are too busy mingling with one another to cultivate ties outside the community. Dense, closely bounded networks circulate familiar—and sometimes stale—ideas, but seldom draw in new information. Open, loosely tied networks are more conducive to creative synergy.11

But small towns are not inherently inhospitable to innovation. Network studies also suggest that dense networks are sometimes necessary to implement new ideas, and resources and leadership may matter more than social ties. Small towns are in reality quite different from stereotypical closed networks in which only stale ideas can circulate.12 Many of the leaders we interviewed were well connected with the outside world. They participated in regional and state governmental associations, agricultural extension networks, farmers’ cooperatives, trucking companies, foundation grant programs, and clergy councils, and more generally, were linked through travel, the mass media, and the Internet. “To quote the book by Thomas Friedman, the world is becoming flat,” explained a farmer who also served as town manager in a community of thirty-five hundred. “You can sit and work anywhere, assuming you have some Internet capability. You don’t need to be on the fortieth floor in some city.” Small towns are also the location of innovative manufacturing firms, experiment stations, and start-up companies.13

Small businesses are sources of innovation, whether in experiments with new technology, consumer products, or marketing. The most innovative small businesses usually benefit from being in or near metropolitan areas where colleges and universities, an educated labor force, and good distribution channels are located. That edge has put small towns in isolated areas at a disadvantage. Yet that situation may be changing as a result of easier communication through the Internet and wireless service, better transportation, and new developments in agriculture and biofuels. In town after town with populations of three to ten thousand, innovative experiments are now evident.14

One example is a small manufacturing plant that specializes in the use of precision laser and plasma cutters to produce parts for large machinery companies. Through computerized ordering and inventory controls along with greater incentive at large corporations to minimize costs through outsourcing, small plants like this one have become more competitive. In other towns, state and federal community reinvestment programs as well as enterprise zones provide tax abatement and interest-free loans to startup firms. Many towns have municipal or county-level economic development directors whose salaries are subsidized by the state. Town Web sites with information about the available labor force, wage rates, housing costs, and schools have become common. Web sites, blogs, and listserves are being used to keep in touch with high school alumni.

The best ideas, according to experienced community leaders, are not far-reaching leaps of imagination—ideas like persuading a major corporation to build a new headquarters in town or inventing some basic new gadget. The innovations that work best are those that build on existing resources. In one town of fewer than two thousand people, a young woman nicely illustrates this point. She is one of seven children, all the rest of whom went away to college, including one to Harvard and one who taught in Japan. But this woman fell in love with a man from her hometown. She has a degree in Latin American studies, and he has one in architecture. Their educations were not the best suited for life in a small rural community. But her dad was trying to start a small business there. She put the practical skills from college to use, working with her father to develop a computerized bookkeeping system and launching a Web site. As the business expanded and began hiring Spanish-speaking workers, she was the natural person to provide translations. Meanwhile, her husband has used his architectural training to start his own business specializing in general contracting. Besides working with her father, she now serves as the county’s economic development consultant. She works with other small start-up businesses to provide reduced utility rates, county property tax exemptions, and low-interest revolving loans. Two of the new businesses she has attracted specialize in welding and metal fabrication. The skills required are ones that people in the community already have or can acquire through evening classes at the high school. About two-dozen new jobs have been created.

In another town, the village manager exemplified the kind of innovation he thought was characteristic of small communities in his part of the country. Interested in saving money on heating costs but wanting to avoid the mess of bringing wood into the house, he installed an external wood-burning furnace that consumed about five cords of wood each winter at a fraction of what oil or gas would have cost. Noting the heat being lost by the outside furnace, he then surrounded it with a greenhouse and began growing spinach for a local farmer’s market. Lately he has been selling unused greens to a farmer who feeds pigs. He says other residents are finding ways to turn personal interests into moneymaking enterprises. A neighbor with wooded acreage is making biodiesel in marketable quantities. A newcomer with a background in chemistry has a small gas chromatography laboratory, which tests for contaminants on food, paper, and textile samples. The lab has clients from around the globe. Another resident runs a small firm that makes specialized apparel products for the military. The town has helped these businesses by renovating old storefronts, upgrading the water system, and applying for grants to improve health care facilities.

Although innovation more often than not connotes new business ventures, it also involves creative efforts to meet needs for social services. Communities with aging residents have benefited from subsidized senior citizens’ housing programs along with programs to provide assisted living, medical care, and prescription medications for the elderly. Other towns face needs for social services because of increasing numbers of new immigrants. In one such town, the community obtained a grant from the state to provide health screening at the local elementary school and expanded its visiting nurse program. It cleaned up a pond that was a public health risk and held meetings for residents interested in participating in a community gardening program. Not having a local newspaper, let alone one in Spanish, it sent information about community services to residents in mailings of monthly water bills and posted notices in local stores.15

These projects cost relatively little, and the more expensive ones were subsidized by the state. Other examples included partnerships between towns and the state to house prisoners, build small solar energy production units, and recycle wastewater for irrigation. With small grants from the state, towns were rehabilitating the facades along Main Street, adding English-as-a-second-language courses at the high school, and subsidizing transportation for the elderly. At relatively modest cost, towns were installing solar energy panels on public buildings, putting up cell phone towers, and finding locations for wind energy units.

Many small communities, though, face needs for social services and infrastructure that require significantly larger expenditures. Hospitals and schools are among the most expensive. Aging gas mains and water lines may need to be replaced. A juvenile detention center needs to be built or an industrial loan has to be provided to keep a manufacturing plant from relocating. State coffers may be too depleted to help. The only way to fund these projects is by raising local taxes—seldom a popular idea.

Angela Lorenzo is the town clerk in a community of thirty-five hundred that was facing the difficult task of having to raise local taxes in order to proceed with the improvement projects that the community needed. The state was in deep financial difficulty, so most of the funding had to be secured locally. The residents took pride in being known as a progressive community, but were less than eager to approve any project that increased local property taxes or required a local sales tax. “We wanted to remain progressive,” Ms. Lorenzo recalls, “and yet not chase people out because of the tax base.”

The solution was an idea that would work in a small town or neighborhood, but would be much harder to implement in a city. The town’s development committee initiated a series of roundtables that met once every six months, were widely advertised, and were small enough that residents turned out to talk about community needs. Then every eighteen months, a community summit was held that drew together the ideas from the roundtables as well as enlisted the participation of business leaders, educators, clergy, and elected and appointed officials. As a result of these meetings, residents felt they had a say in deciding what projects deserved their support. When we talked with Ms. Lorenzo, the community had recently passed a six million dollar bond issue to renovate the local nursing home and a twenty-four million dollar bond issue to construct a new hospital.

Communication is another aspect of infrastructure that requires creativity. Emergency 911 phone services are accommodating the fact that a growing number of rural residents use cells phones rather than landlines. When a 911 call comes by landline, the caller’s location appears on a computer screen, but that does not happen if the call is made from a cell phone. Towns have been working with state officials and telephone companies to circumvent this problem by installing GPS chips in cell phones, and in other areas, experimenting with voice-recognition text-messaging systems. Another challenge involves arrangements for videoconferencing and Web-based learning in small-town schools. A gifted high school student in a small isolated community wanted to take advanced placement calculus via videoconferencing, for example, but the telephone company offered only audio conferencing. Regional planning commissioners worked to arrange service through a different telephone company.

Regional planning efforts are facilitated by Web-based networks and state agencies that mandate cooperation, for instance, through participation in county sales tax programs, or for distributing state funds for street and highway improvement. The possibilities for formal and informal cooperation are reinforced by the fact that towns are often located in close proximity to one another. For example, nearly two-thirds of small nonurban towns are located in counties in which there are at least five other towns. A third of small nonurban towns are also located in a county that has at least one town with a population of twenty-five thousand or more (see figure 6.3).16

Figure 6.3 Neighboring towns by town size

While the proximity of other small towns makes it possible and sometimes even necessary to cooperate on projects, town leaders just as often talk about these neighbors as competitors. Competition may have historic roots in conflicts over the location of railroads and county courthouses, and it likely is perpetuated by athletic rivalries. As we have seen, residents also bemoan the fact that fellow residents are commuting to another town to work or shop, or that a larger town’s Walmart or shopping center is taking business from local merchants.

Nearest-neighbor analysis provides a method for assessing the effects of competitors with various characteristics, whether that involves competition between rival automobile models or towns that literally are close neighbors. Using latitude and longitude coordinates, nearest-neighbor analysis facilitates identifying the town that is closest geographically that has particular characteristics. One of these characteristics is population size. Town leaders we talked to frequently speculated that the population of their own town was being adversely affected by the presence of a larger town nearby.

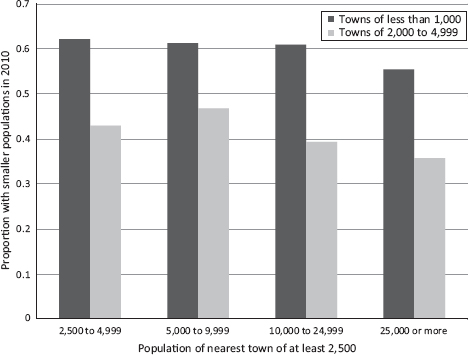

In figure 6.4, the effects on the probability of towns declining in population between 1980 and 2010 when the nearest town of at least twenty-five hundred is of varying size are shown. The figure compares these effects for small towns of fewer than a thousand residents in 1980 and slightly larger towns of between two and five thousand residents in 1980. For the smallest towns, the probability of losing population is better than 60 percent, and it makes little difference whether the nearest neighboring town has only a couple thousand residents or more than ten thousand residents. Only when the neighboring town has more than twenty-five thousand residents is there a slight reduction in the probability of the small town losing population.17

For the somewhat larger towns of two to five thousand residents, the probability of losing population is lower in each comparison than it is for the smaller towns of under one thousand residents. The probability of losing population is slightly higher if the neighboring town is slightly larger, i.e. has between five and ten thousand residents. But then the probability of losing population decreases as the nearest neighboring town’s population increases.

These results make intuitive sense. Towns of under a thousand residents are unlikely to have schools and professional services, such as doctors and dentists, of their own. Housing may be cheaper, but there is little advantage of living there instead of in a larger community nearby, even if that larger community is still relatively small. In contrast, towns of at least two to five thousand are more likely to have services and businesses that make them attractive as places to live, especially if there is a town of ten thousand or more that can provide jobs. Thus, it is beneficial for these towns to be located in the vicinity of a larger neighbor.

Figure 6.4 Effect of size of nearest town

Figure 6.5 Effect of five neighboring towns

Figure 6.5 presents the results of nearest-neighbor analysis in which the populations of the five geographically closest towns are considered. The comparisons are between towns for which the mean population of the five nearest towns is smaller than the town’s own population, or larger. In other words, the comparison makes it possible to ask for a particular town of varying size whether that town is among the smaller ones in its vicinity or is one of the larger ones.18

The results show that towns of under a thousand residents have a better than 60 percent chance of having declined no matter how they compare in size with their five neighboring towns. The chances of having lost population are only slightly improved if their neighbors are larger—similar to the result in the previous figure. But for towns that have at least a thousand residents, all the way up to towns that have between ten and twenty-five thousand residents, having larger neighboring towns is actually beneficial. Towns with larger neighbors are consistently less likely to lose population than those with smaller neighbors.

Of course, there are many other factors that determine whether a town loses population, holds its own, or grows. But this evidence counters the impression that it is disadvantageous to have larger neighboring towns. True, the chances of losing population are reduced if the size of one’s own town is larger. And yet taking that into account, those chances of declining are further reduced if there are some larger towns in the vicinity. In those cases, residents of the smaller towns can more easily find jobs in the larger towns.

RESISTANCE TO INNOVATION