The following additional rules can be applied to any ADF scenario and each highlights a particular tactical nuance of the civil war battlefield. While there is solid historical evidence for each of these rules, their use can add additional complexity or may alter play balance, and consequently they should be treated as rules that should be used only by mutual agreement between the players or by the game master’s choice.

The basic rules for ADF have each regiment represented by two stands, each with the same number of figures, so that all units would be depleted at 50 percent casualties. However, for gamers that prefer to model specific regiments where the actual strength is known, a more accurate figure representation can be accommodated by not requiring that each stand have the same number of figures. For example, a 420-man regiment would be most accurately represented by a total of seven figures – one stand of four figures and one stand of three figures. If this is done, losses should be taken as follows:

In ADF, regiments of two, three and even four stands can be used on the same gaming table. Here four large Union regiments are closing in on three Rebel regiments, two of which are obviously smaller units. (Alan Sheward)

If a regiment has unequal stands and it is an Elite or Veteran regiment, then losses are first taken on the stand with the most figures to show the greater resilience of these units. However, if that regiment is a Trained or Green regiment then its first losses should be taken against the stand with the least number of figures to show the greater fragility of less experienced units. Adapting this rule, however, tends to exaggerate the “staying power” of Elite and/or Veteran regiments versus Trained and/or Green regiments.

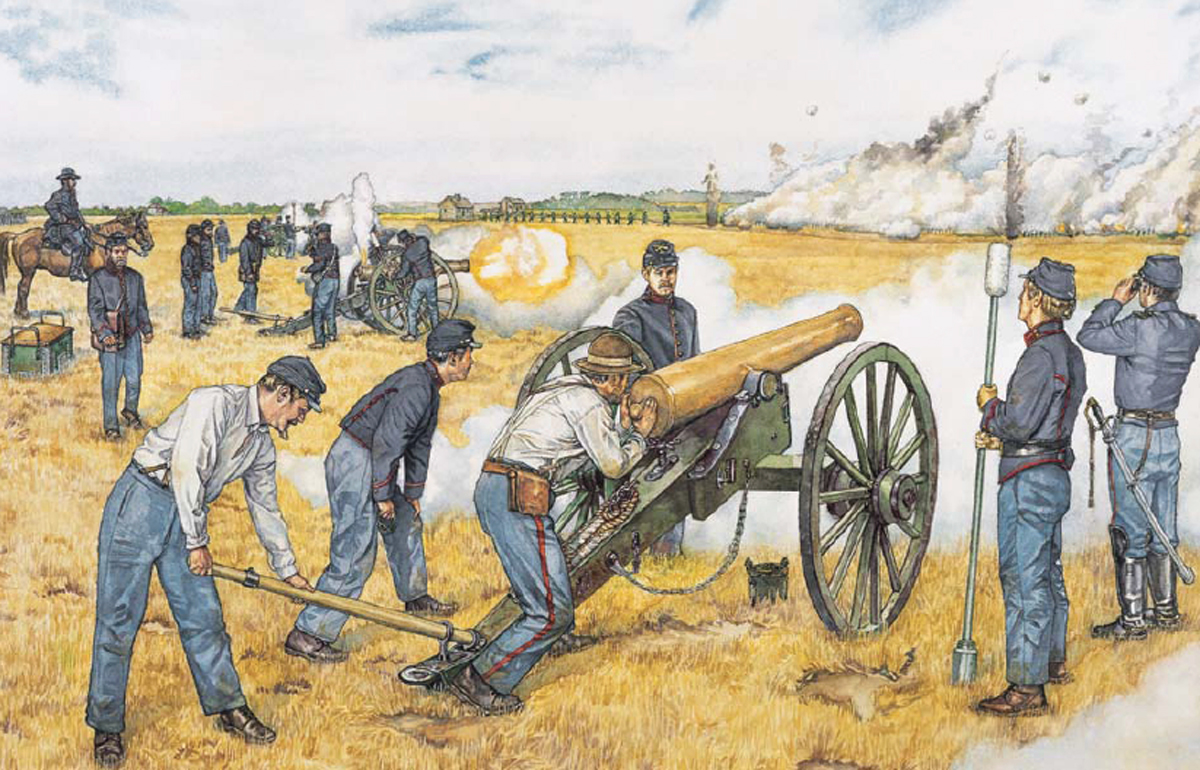

The storming of Casey’s Redoubt, by Steve Noon © Osprey Publishing Ltd. Taken from Campaign 124: Fair Oaks 1862.

In any scenario where a specific arrival or entry time is indicated, that is the historical entry time as best as can be determined considering that even “reliable” historical sources often recorded significantly different times for the same events. There is always the possibility that an aggressive commander would have hurried his troops to the sound of the guns or, more likely, become a victim of unexpected traffic jams, confusion, or the always present frictions of war. To add those possibilities, use the following rule:

At the start of the scenario, roll a 1D6 for each arriving unit one turn before its scheduled arrival. If a 1 is rolled, then the unit comes in one turn earlier than scheduled – right now. If a 2, 3 or 4 is rolled, it comes in exactly as scheduled. If a 5 or 6 is rolled it comes in one turn later than originally scheduled. If there is a scheduled arrival sequence of brigades – such as Early’s Confederate division – coming in at the same location, but sequenced one turn apart, roll once for the whole division to determine if the whole “sequence” is one turn early, on time, or delayed by one turn.

On a regular disengagement, the unit can stop running once it is behind friendly forces. However, on an “extreme disengagement” (see below) the unit must take the full disengagement movement distance. A disengaging unit drops one morale level, but never below “shaken”.

The standard disengagement rule allows a unit to retreat with a double disorder move out of harm’s way, with the firer losing one die and the retreating unit dropping one morale level. This rule assumes that the regimental commander is attempting to maintain some level of control of his regiment as they pull back. However, sometimes the situation has become so extreme that the disengagement becomes outright flight. Such was the case of Colonel Jesse Appler and the 53rd Ohio in the early hours of the Battle of Shiloh. After having repulsed two determined attacks by the 13th Tennessee, Appler suddenly lost his nerve and ordered “Retreat and save yourselves!” And run they did, with most of the regiment dissolving into a fleeing herd. To use this option, use the following rule.

If an infantry or cavalry unit wishes simply to run, it may make an “extreme disengagement.” To do so, it retreats with a triple disorder move and all fire against it still loses one die. However, it ends its movement at two morale levels lower than when it began but never worse than routed. Hence a good-order unit will end as a shaken unit, but all others will end as a routed unit. As with a normal disengagement, an extreme disengagement can be done as an action or a reaction. If an artillery unit uses this option, it obviously would abandon its guns, so the battery would be removed.

Being in the wrong formation at the wrong time made even the best troops very nervous. One of the more unsettling conditions was being caught under fire while in a road column. By late 1862, even if a new politically-appointed brigade or division commander – or a new wargamer – did not know better, the regimental commanders and the soldiers themselves almost certainly did. To reflect their inherent battlefield awareness, incorporate this rule:

If a unit in road column comes under any fire that results in a morale check – regardless of whether the unit passes the morale check or not – that road column must immediately stop and use its next action or reaction to change formation into either a battle line or an extended line facing the enemy. If it was moving as part of its second action and consequently would not have an action left, it simply stops and must use its next reaction to change into a battle line or extended line.

The movement distances for ADF take into account the extra time it might take for the commanders to evaluate a situation, decide what they wanted to do, and have their orders clearly understood by their subordinates – all of which adds to operational delay. However, if all a regiment did was to move as fast as it could and that was clearly understood at the start of its “actions,” and it did not stop to fire, reform and received no hostile fire during its continued movement, then it could go somewhat further than the “normal” distance for its two ADF actions. For example, on the first day of Gettysburg at about 3 p.m. Hay’s Brigade of Early’s Confederate Division came on to the field and was unopposed. Early gave him the order to keep advancing and not to stop until he hit the Federals. Hay’s Brigade did just that; they rushed forward in extended order and about an hour and 4,000 yards later his somewhat winded but exhilarated brigade, along with Avery’s Brigade, slammed into Coster’s Union Brigade and routed it just outside of Gettysburg at the brickyard. If continuous movement is allowed, adopt the following rules.

Only Veteran or Elite active units, or Veteran or Elite unit groups in good order, may use continuous movements. At the start of its active turn, if a unit or unit group declares that for the its next two actions, it is doing nothing else – no firing, no formation change, no charge and is not forced to make a morale check of any kind – it gets an extra action of movement. However, it ends its turn in disorder and must roll a 1D6 for “stragglers.” If the unit is forced to take any morale check while doing this, it does not get the extra movement, but still ends its turn in disorder and must still roll a 1D6 for “stragglers.” Units in disorder or worse cannot use continuous movement.

If called for by the scenario or if any unit uses continuous movement, that unit must roll a 1D6 at the end of its final movement for stragglers, in addition to now being in disorder. The number rolled with a 1D6 is the number of stragglers it has, and the rolled 1D6 die is placed by the unit to indicate how many stragglers there now are. This is a temporary reduction in the unit’s figure count, but until the stragglers are recovered those figure losses are treated as “real,” and negatively affect both a unit’s Firepower Points (FPs) and its Basic Modified Morale Point (BMP) if the number of stragglers has caused the unit to lose a stand and reduced it to a depleted status.

If a unit with stragglers chooses to fire, its FPs are reduced by the number of stragglers it currently has. If a straggled unit is forced to take a morale check and the number of its stragglers has temporarily reduced it to less than one stand’s worth of figures, the unit takes that specific morale check as a depleted unit. If a unit suffers casualties while it still has stragglers and if the combined straggler loss, previous losses and current fire loss is equal to or more than the figures the unit originally had, that unit is assumed to have disintegrated and is removed from the game. If a unit routs while still having stragglers, the temporary straggler figure loss is converted to a permanent figure loss.

At the end of an hour, Hay’s Brigade covered about 4,000 yards and would be part of a joint attack that would drive Coster’s Brigade out of the “brickyard.”

To recover its stragglers, a disordered unit reforms back to good order by spending a reaction or action to reform, and rolls a 1D6 once to provide the number of stragglers it recovers (although never more than it lost). If the roll was less than the number that was lost, then the difference becomes a permanent loss. If a shaken unit has stragglers, it must first rally to good order before it can roll for straggler recovery. Routed units cannot roll for straggler recovery.

Experienced artillery crews learned that a risky but often effective way of pulling out of a difficult situation was to fire a full battery salvo and then, while its position was temporally covered with its own smoke, quickly limber and rapidly pull out. As with many such clever tactical expedients, sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. To offer artillery batteries this option, use the following optional rule.

Only Veteran and Elite batteries – not Green or Trained – may fire and then spend half a movement to limber and take a half limbered move away from the enemy, while covered by their own smoke. Such a move must be declared prior to doing it and can only be done as a combined two-action – fire & limber/move – turn. If so declared, any fire directed against the battery as it limbers and withdraws gets neither the -3 DRM benefit for being unlimbered nor the DRM penalties for being limbered. Any fire directed against the battery while this is being done is a dead even shot, with no DRM benefits or penalties. If one hit is scored against the retiring battery, the first hit is considered to be a horse hit. If two hits are scored against the retiring battery, then it is resolved as one horse hit and one section destroyed.

Jones’ artillery battalion deploys to support Jubal Early’s division. (Patrick LeBeau & Chris Ward)

Once the lines were established and if the terrain permitted it, the preferred Union defense was to move infantry up front along with a battery in direct support – usually Napoleons – to deliver point-blank canister fire into any attacking infantry. This would be supplemented with other artillery batteries – usually rifles – firing over the heads of the infantry with solid shot, shell or case shot so as to break up the attacking formations before they reached musket range. The Union batteries, having more reliable ammunition then their opponents, were consistently more comfortable firing over the heads of their own troops than were their Confederate counterparts. The rules for this are as follows:

Union artillery can do non-canister fire over the heads of friendly units if the battery or the targeted unit is at least one elevation higher than the intervening friendly unit, provided that both the firing battery and the targeted unit are at least two inches from the intervening friendly unit. Confederate batteries can also fire over friendly units in the same manner, but either the battery or the target must be at least two elevations higher than the intervening friendly unit and both the firing battery and the targeted unit have to be at least three inches from the intervening friendly unit.

Union artillery at the battle of Malvern Hill, July 1, 1862, by Stephen Walsh © Osprey Publishing Ltd. Taken from Campaign 133: Seven Days Battles 1862.

While canister was very seldom fired over the heads of friendly infantry, it was occasionally done when in desperate situations. In the final defense of Seminary Ridge, Stevens’ battery of six Napoleons would fire 57 rounds of canister directly over the heads of the 2nd and 7th Wisconsin regiments less than 80 yards away on the down slope. While the effect was staggering against the attacking Confederates, it also had an unsettling effect on the Union infantry underneath this canister storm. Lieutenant Colonel John Callis of the 7th Wisconsin claimed that he tried unsuccessfully to get the battery to stop, as it was killing some of his own men.

Long-range canister – but not point-blank canister – may be fired over the heads of friendly infantry as per all the regular rules for firing over friendly infantry. However, every time this is done the intervening friendly infantry must take a fired-on-rear by artillery (+4 to MMP) morale check. In any case, Union artillery can only do this if it has one elevation advantage, and Confederate artillery must continue to have a two-elevation advantage.

Normally shaken units cannot move towards the enemy. However, it would be allowed if they had a leader attached and provided that the forward movement was all done behind non-skirmishing friendly units.

Any time there is a legitimate disagreement as to whether a unit can see a specific enemy unit or whether the visibility could be defined as obscured, then firing can still be allowed as area fire, which is done like any other fire but with one less die.

Usually, if a leader is adjacent to a unit, his ability to improve movement and morale depends solely on his Leader Benefit (LB), which can be converted to extra inches of movement or a beneficial Modified Morale Point (MMP). If, and only if, a leader is actually attached to a unit, will that unit get a beneficial firing Die Roll Modifier (DRM). However, a case can be made that the ability of a leader to offer these benefits may actually depend on how involved he was with his brigade and/or one particular regiment. For example, just being seen nearby would probably be enough to bolster a unit’s sagging morale, but to actually improve a regiment’s firing might require his personal direction. To reflect these nuances more precisely, use the following rules:

If a leader is attached to any one regiment and if all the regiments of that brigade are contiguously adjacent to the unit with the attached leader, when they move as a unit group, they would all get extra inches of movement equal to the leader’s LB, provided the regiments remain adjacent to the leader or contiguously adjacent to a unit that is adjacent to him.

If a leader is physically adjacent to a regiment, that regiment receives an MMP modifier equal to his leadership bonus. Depending on the actual unit configurations, it is possible that up to four adjacent regiments could receive this morale benefit.

If, and only if, a leader is attached to a particular regiment can his LB be used to improve that one specific unit’s firing as a beneficial DRM equal to the leader’s LB. A leader can only benefit the firing of one unit or a single combined firing of adjacent units. However, the total combined FPs are still limited to 18 FPs for artillery, 16 FPs for infantry, and 14 FPs for cavalry.

All artillery leaders have an LB, which can help morale and extra limbered movement – not unlimbered movement – but only if an artillery leader has a specific (1 Artillery LB) can he help the artillery firing of a battery or battery group.

Howard attempts to rally XI Corps, by Adam Hook © Osprey Publishing Ltd. Taken from Campaign 55: Chancellorsville 1863.

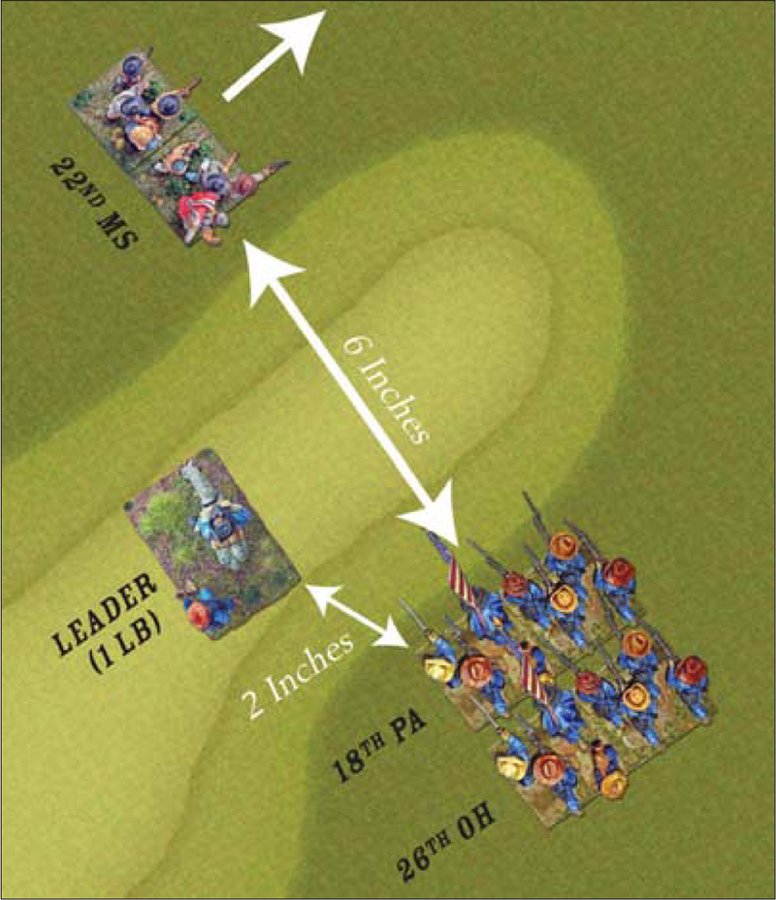

Any (1 LB) or better leader has a reaction radius equal to twice his LB rating in inches. So a (1 LB) leader would have a reaction radius of two inches. Then if that leader can see an enemy action he can order any one friendly unit or one unit group that is within his reaction radius to make a normal move or make a disordered charge. The leader would have to accompany the unit making the move or the disordered charge, and would have to roll for leader casualty.

Example: Normally, the 18th Philadelphia and 26th Ohio regiments could not react to the 22nd Mississippi Regiment moving across their front since the hill blocks their visibility and they cannot react to what they cannot see. However, since the leader can see the moving 22nd Mississippi, and the unit group of the 18th Philadelphia and 26th Ohio are within his reaction radius, he can order them to follow him and make a disordered charge over the hill and into the flank of the moving 22nd Mississippi. Even though the 26th Ohio is more than two inches away, it could join the charge since it is adjacent to and in the same formation as the 18th Philadelphia, and therefore is part of a legal unit group.

In most cases, a unit’s legal reactions are limited to firing, re-forming, rallying, and with some restrictions, a countercharge. For a unit to react to an enemy, that unit has to be able to see an enemy unit doing something, or if that unit can’t see the enemy unit due to visibility restrictions, the reacting unit would have to be within two inches of it to react to it.

Normally, moving or charging is not a legal reaction. However, if a unit has a leader attached and either the unit or leader can see the “triggering” unit, or is within two inches of it, then that one unit may make a move or a charge as a legal reaction.

Many gamers have their 15mm regiments mounted for Johnny Reb III (JR III), and while they prefer the look of JR III’s larger 4-stand regiments, would like to use the ADF game mechanics, as ADF does away with the necessity of marking what each unit is going to do each and every turn. First, the 4-stand BMP morale chart will work nicely for the 4-stand regiments of JR III. The ground scale and turn time scales are close enough that it works for gaming purposes.

Since we would be using the JR III 4-stand units with one figure equaling 30 men, we will maintain the JR III 15mm ground scale of one inch equaling 50 yards, so that our scale regimental frontages stay the same. In JR III a battle line can move 6 inches (300 yards) in 20 minutes and can do a moving fire with one less die, while in ADF a 15mm battle line can also move 6 inches (300 yards in the JR III 15mm ground scale) in 30 minutes and then do only one fire action. In both game systems, moving fire is not as effective as a unit that is not moving and doing only firing. Of course, in ADF the regiment could choose not to fire and use both actions as movement actions, which would mean it has moved 600 yards in 30 minutes, but then it would have no active fire. The weapon ranges will be slightly different. At 50 yards per inch, in JR III the normal rifle-musket ranges is four inches or 200 yards, while in 15mm ADF (with the JR III 15mm scale) it is three inches or 150 yards. For firing, since you are “shooting” with twice as many figures, each shot will kill more figures, but since the target regiment also has more figures, the percentage of loss will be about the same per shot. There will be some anomalies, but no more than in any other wargame or in real battle itself.

When dismounted cavalry performs a point blank fire, it still gets to fire both its long weapon and its pistols, but not as one combined factor fire. Instead, they would fire their long weapons at short range, take a fear-of-charge morale check, and then fire their pistols at point blank range.

When cavalry is deployed in less than a full regiment or brigade, the basic 1:30 figure ratio usually works best to portray those detached battalions. However, when entire cavalry regiments or brigades are deployed as entire units or when cavalry makes up the bulk of the battle force (such as at Brandy Station) or when they have been permanently dismounted, then a 1:60 ratio may work better. In that case, while they still might use cavalry weapons the troopers would then fire on the 1:60 infantry fire line.