CHAPTER THREE

Test Your Memory

How good is your memory, and how long can you remember information? Before you begin the process of strengthening your memory, it’s a good idea to understand the point at which you’re starting.

In this chapter, you’ll find a short test to determine your memory span—the amount of time you can keep in your short-term memory lists of words, numbers, or letters. This is a good starting place for determining the kinds of memory tools you will want to use to strengthen your memory, increasing its capacity to hold information for both the short and long term.

If you want to delve more deeply into other kinds of memory testing, a number of comprehensive tests are available to determine your memory’s capacity for storing information, the length of time information remains in your working memory, and your ability to recall new information quickly—or at all. Here are some of the most recognized and trusted tests used by psychologists and neurologists.

- Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS): Probably the most widely used scale of adult memory, this package of exams includes seven subtests that score your auditory memory, visual memory, visual working memory, immediate memory, and delayed memory. One of the functions of this test is to help neuropsychologists differentiate between people with dementia or brain disorders and those with normal memory functioning.

- Memory Assessment Scales (MAS): This test assesses short-term, verbal, and visual memory functions, and is one of the most widely used instruments by professionals. It contains twelve subtests for verbal span, list learning, prose memory, visual span, visual recognition, visual reproduction, and recalling names and faces. If you have serious concerns about your memory, or if you are certain that you or a loved one are experiencing memory loss, it could be worth your time to consult a psychologist who can administer this test.

- Self-Administered Geocognitive Examination (SAGE): Specifically used to test for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, this test can help you determine if you have mild cognitive impairment, a precursor to early dementia.

- Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam: Developed in conjunction with the Department of Veterans Affairs, this test looks at cognitive function and memory, using words, numbers, and clock faces to determine your current state.

A Memory Span Test

The following test will give you an idea of the number of words you can remember from a list. The entire test will take no more than ten minutes to complete.

This test should be used for your own information and entertainment, not as a clinical assessment of your cognitive abilities. Everyone has good days and bad days, or days with extra doses of distractions and worries. A low score does not necessarily mean that you have developed a neurological disease or that you are not as intelligent as other people. In fact, this test does not measure intelligence—it is meant to help you understand the workings of your own short-term memory, so that you can take steps to improve it if you choose to do so.

If you believe that you are experiencing real memory impairment, seek a neuropsychological assessment from a qualified specialist.

What to expect: The following is a list of words. You will be asked to look at the words for a set period of time, and then write down the words as well as you can remember them. These words are still on the page, of course, so you’re working on the honor system. Once you’ve closed the book, there’s no peeking! This is not a test to determine how smart you are, so it doesn’t matter how many you get “right.” This is a test to see how well you can remember what you’ve read—the capacity and duration of your short-term memory. It’s important that you take the test correctly to give yourself a useful assessment of your memory’s abilities.

Here’s what you will need to take the test:

- A sheet of paper

- A pen or pencil

- A timer or stopwatch that can go as long as two minutes

A Short-Term Memory Test

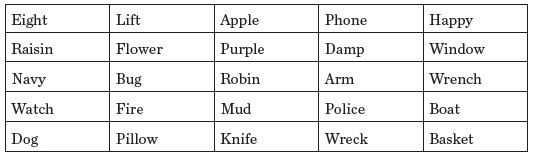

In the following table, you will see a list of words. Look at these words for two minutes, and memorize as many as you can. Do not write down anything until the two minutes are up. When your timer rings at the end of two minutes, close this book and reset your timer for two more minutes. Write down as many words as you can remember in those two minutes.

When the timer goes off again, open the book and count how many of the words you remembered. Also note if you wrote down any words that were not on the list.

Ready? Go.

When two minutes are up, set aside the book and write down all the words you remember.

Now you’ve opened the book again and you’re looking at the preceding list of words. How many did you remember? Write down the number of words, and prepare for the second exercise.

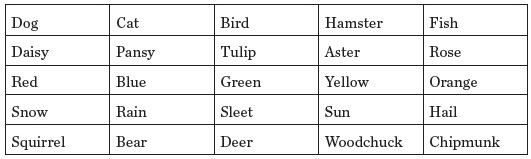

Here is another list of words. The process is the same: Give yourself two minutes to memorize this list. When the two minutes are up, close the book and write down as many of the words as you can remember. At the end of two minutes, put down your pen and refer to the book to see how many words you got right.

Is your timer set? Go.

When the timer goes off, set aside the book and write down all the words you remember.

If you’re reading this, you have spent two minutes trying to remember the words on the previous page. How did you do? Did you remember more of the words in this list than in the first list?

Now let’s switch things up and try a test using numbers. This test will help you gauge your short-term memory’s limit for a certain quantity of items.

Again, you will need to look at a number, set aside the book, and write down the number as best as you can remember it. It’s a good idea to cover up all the other numbers on the page following the one you’re looking at to be sure you don’t see them and start to remember them before you’re ready. Use an opaque piece of paper to do this.

Look at each number series for ten seconds, then turn over the book to hide that number, and write it down. When you are ready, go on to the next number. Look at it for ten seconds, and then write down the new number. Keep going until you can’t remember every digit in the new number series.

Is your timer set for ten seconds? Go.

492

3543

84302

557691

6345703

45930275

230735829

1928750238

43960472084

697835021952

2039482309482

23094823948230

How many digits were in the largest number you could remember? If you’re like most people, your recall topped out at seven or eight digits, nine at the most.

Let’s look at your results. Add up the number of words you remembered on the first test, the number of words you remembered on the second test, and the number of digits in the longest number you remembered on the third test.

How did you do?

- 28 or higher: You have a strong short-term memory. The tools in this book will be easy for you to master.

- 18 to 27: You are in the normal range for short-term memory. The techniques in this book may help you increase your memory’s capacity and power.

- 17 or below: What’s going on? You may be distracted today by issues other than your memory, or maybe you’re not feeling as well as you’d like. Take these tests again on another day, and try out some of the techniques in the upcoming chapters. If you have seen a pattern of memory issues, however, talk with your doctor to see if you need a professional assessment.

Chances are you found the first list of words and the numbers harder to remember than you expected. Short-term memory is more limited than you may realize, as researchers have repeatedly discovered for more than fifty years.

You met George Miller in Chapter One, but let’s take a closer look at his research. Miller was the first psychologist to measure the limitations of short-term memory, pegging this limit at what he called “the magical number seven, plus or minus two.”

Miller reviewed the work of many other experimental psychologists in a 1956 issue of the Psychological Review, and his conclusions have become the standard by which short-term memory has been measured. He determined that when people are presented with one-dimensional information—that is, with a series of random words, objects, or numbers that have no particular relationship with one another—the human short-term memory can hold no more than seven of these, plus or minus two.

When even one additional dimension is added to the words or objects, for example, the object takes on new meaning. That’s why you probably did not remember more than seven of the words in the first list, but you remembered many more of the words in the second list. The first list showed you a bunch of randomized words with no interrelationship. The second list gave you five groups of related words: pets, flowers, colors, weather, and woodland creatures.

The numbers start out being fairly easy to remember, but the addition of even one digit can suddenly make a number too unwieldy to retain in short-term memory. Perhaps you found yourself reciting the numbers aloud to remember them, or breaking them up into chunks, the way we break up telephone numbers. This creates associations between digits that did not exist when you were first presented with the long string of numerals. You may now have a better understanding of the patterns of phone numbers, and the ingenious way that they were designed from the outset to be easy to remember.

Now, here’s a final question: Do you remember any of the words and numbers you were tested on a few minutes ago?

If your answer is no, or if you can only remember one or two words, you are entirely in the normal zone. Your brain had no reason to retain any of the information you just memorized, so your short-term memory quickly discarded it. The random numbers and words you processed have no special meaning to you. If you decided you wanted to remember them, you would need to move them from your short-term memory into your long-term memory, and store them until you needed to access and retrieve this information.

In Part Two of this book, you will learn about a number of techniques used by leading memory experts to increase the capacity of short-term memory, move new information into long-term memory, and improve your ability to access stored memories at random and retrieve them throughout life.