In atrocious winter weather, a small army marched north from London. Torrential rain had led to widespread flooding. Roads and bridges were down, and effective reconnaissance impossible. The commander was Richard’s father, Richard, Duke of York. Tragically, he had been lured into an awful trap. He had separated his forces, leaving a contingent behind to guard against insurrection in the West Country. But these rebels had in fact undertaken a rapid, secret march and were now ahead of him, joining with further reinforcements. York was alarmingly outnumbered. He had anticipated time to gather loyal troops with a rendezvous at his Yorkshire residence of Sandal Castle, and then take war to the enemy. His column was encumbered with a siege train and could only move slowly. But there was not time for his followers to meet him. His position grew increasingly desperate. He reached Sandal just before Christmas, short of supplies and menaced by his opponents. A few days later, on 30 December 1460, he was overwhelmed in battle.

York’s family and closest followers remembered the occasion of his death with one highly charged phrase, ‘the horrible battle’. According to family tradition, York met his end in heroic fashion. A party of his men, sent foraging for supplies, was suddenly threatened by the enemy. He charged from the high ground of Sandal Castle in a brave attempt to rescue them. It proved a disastrous mistake. He was unaware of his opponents’ strength, and his small detachment was surrounded and cut down in particularly savage fighting.1

The violent fate of Richard’s father at the battle of Wakefield strikingly foreshadowed his own at Bosworth. Both men mounted cavalry charges, taking the fight to the enemy. Both were cut down in fierce hand-to-hand combat. The comparison extends further. Both had marched to battle to champion the rightful claim of their bloodline to the highest prize of all, the throne of England. Their right had been wrested from opponents through tarnishing their rivals’ issue with the stigma of bastardy. Inevitably, this slanderous affront was challenged by force of arms, and it gave a terrible bitterness to the conflict, which assumed the brutality of a family vendetta. No niceties of convention would be respected here. The bodies of both men were mutilated in the aftermath of battle, and denied proper burial.

It is the startling similarity between the two battles, some twenty-five years apart, that first intimates to us that Richard III is not the maverick loner, pursuing his own agenda at the expense of all family susceptibility, but that a broader pattern is being drawn, with Richard’s own action one line within it. A better understanding of this pattern must begin with Richard’s own relationship with his father.

Our present understanding of the power of father-son relationships can distort our sense of the medieval past. In the Middle Ages, an aristocratic child would have little contact with his father, and his upbringing would be the responsibility of nurses and tutors. Richard, who was eight at the time of his father’s death, had little real experience of the man, who would have been a remote, if impressive, stranger. So how would Richard remember him?

Having little actual recall of the man himself, the boy Richard, surrounded by the custodians of the family legacy, would learn to remember and understand a figure depicted by those around him. A mythology is bigger than a memory, and Richard grew up in its shadow. As its power gained a hold on his imagination, he came to see himself in this mythic father’s likeness and thus as his true heir. Physically and temperamentally resembling him, and bearing his name, he carried the legacy of a right to the throne denied by the violence and treachery of others. To illuminate this legacy we need to explore these mythic elements in more detail.

Perhaps the most important vehicle for the preservation of his father’s memory was a religious house that had particularly benefited from his patronage, at Clare in Suffolk. And it was here that the image of this lost, heroic father, who had come so close to securing the crown of England, was promulgated. A chosen religious community in the late Middle Ages fulfilled the same function as a modern-day presidential library, acting as a repository for documents and other memorabilia, and serving as a centre of scholarship and learning, designed to disseminate the good works and reputation of its patron.

The significance of such a hallowed collection was its focus on a three-fold representation of Richard, Duke of York – almost a triptych: the worthy statesman, the pious man chosen by God to be king, and the courageous warrior beleaguered by his enemies. A painted scroll in the collection at Clare describes York as man of destiny, raising his sword to vanquish his enemies, in pursuit of the path chosen for him by God. Another manuscript, translated into verse, makes accessible the deeds of renown of Stilicho, a notable general of the late Roman empire, betrayed by the machinations of a jealous court party – a story both familiar and relevant to York’s family. These memorabilia gained a posthumous force through York’s sudden, tragic death. The repository at Clare almost represented a shrine to an uncrowned king. Those who kept this repository might well have seen themselves as guardians of a flame, designed to be rekindled to illuminate the realm of England and redound to the glory of the house of York. It was the circumstances of York’s death that gave this collection its extraordinary power within the family, and to those who felt themselves heirs to his thwarted ambition. And Richard, as we will see, viewed himself as his father’s ultimate successor.2

York’s defeat and death at Wakefield came as a terrible shock to his family. Perhaps the most painful aspect would have been the realisation that his own mistake had led to this disaster. His friends and supporters had been unable to join him as planned at Sandal Castle, and the enemy had been present in far greater numbers than anticipated. A more prudent course of action would have been to hold firm within Sandal’s defences and send for help as soon as possible. Had York not charged impulsively to the rescue of the foraging party, the outcome could have been so very different.

To ride to the help of followers at risk from the enemy was a noble gesture. But however admirable the sentiment, contemporaries could not help but regard it as at best ‘incautious’ and at worst a pointless waste. Such criticisms were understandably too difficult to bear, and the family’s interpretation of the dreadful events at Wakefield underwent an all-important shift; York had been betrayed without by unscrupulous opponents breaking a Christmas truce, and within by turncoat supporters who had already cast their lot with the enemy. His death was thus seen as a brutal murder, and the subsequent mutilation of his body a violation of honour. His decapitated head was ironically crowned in mockery of his pretensions to the throne. This in the eyes of his supporters came to represent an icon of almost Christ-like significance. As the legend evolved, this imagery became more pronounced, and one version had Richard crowned and taunted on a hillock before being cruelly put to death.

We can see how the understanding of an event might be altered in hindsight through a selective perception of what had taken place. The medieval equivalent of the spin-doctor would be called upon to protect family honour. A similar shift can be found in accounts of the battle of Baugé, fought between the English and the French, supported by their Scottish allies, six years after Agincourt, at which Henry V’s brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence, was defeated and slain. Clarence was seized with a sudden, overwhelming desire to engage with the enemy one evening while he and his followers were having supper. Hearing a report that they were in the vicinity, he at once leapt up from the dinner table, leaving those around him with no option but to join a pell-mell advance in the gathering twilight. Those caught up in this highly spontaneous undertaking had very mixed feelings about it, and vigorous debate ensued in the ranks. The worst fears of the doubters were entirely justified. Clarence and his advance guard careered across a river, colliding with a larger than expected body of enemy troops. A chaotic skirmish broke out in the gathering dusk, which quickly cost Clarence his life, with his remaining men-at-arms killed or captured. Such was the velocity of this disastrous engagement that the English archers only arrived on the scene when darkness had fallen and the battle was decided.

It comes as no surprise to find many English commentators severely critical of Clarence’s actions, and for his own closest followers and supporters his good name had to be retrieved. So they depicted Clarence as the victim of treachery: the breaking of an agreed truce while he was leading a reconnaissance party. This unlikely scenario satisfied those to whom it was both unacceptable and unmentionable that Clarence had died as a result of his own foolish impetuosity. His idiotic charge was therefore dressed in the garments of a measured action, seized upon by a duplicitous opponent.3

There is a strong resemblance here to the treatment of Wakefield within York’s own family and entourage. It was extremely unlikely that York’s adversaries had agreed to any form of truce, such was their hatred of the man and what he stood for. But blaming the enemy was a palatable distraction from the painful reality of York’s terrible misjudgement. It would be easier to focus a righteous anger on treacherous opponents than to speak ill of a dead leader. An heroic death was infinitely preferable to the stupid waste of a life.

Where a renowned figure appears to have acted rashly and without much thought, there seems to be a strong impulse to impute a cunning and pre-meditated killing plan upon opponents. In the thirteenth century the charismatic leader Simon de Montfort was caught in an apparent trap at Evesham. His heroic charge at the main strength of the enemy position carried little chance of success and he and his followers were cut to pieces. A recently discovered source reveals that the charge may have been unnecessary, for an escape route out of the town still existed and de Montfort and his followers could have lived to fight another day. It might have seemed dishonourable to have retreated in this way, but the violent charge, however heroic, seems almost like the rash embracing of a noble death. But soon after the battle a cult of Simon’s memory developed a different emphasis. His apologists now chose to concentrate on the unscrupulous killing plan agreed by his opponents before battle, brought to a terrible fruition in the murder of Simon and the mutilation of his body on the field of combat.4

This alternative view of Evesham consciously used biblical archetypes to transform the manner of Simon’s death. He became a defender of a just cause, prepared to sacrifice his life for a higher ideal. The idea of violent death in battle was replaced by that of an assassination, with Simon disarmed, mocked and then cold-bloodedly despatched. Although we have little detail on the exact manner of York’s death at Wakefield, we know his son Edmund was probably murdered in the battle’s aftermath and it is significant that accounts soon placed similar ingredients in the story, with York also being disarmed, mockingly saluted and then cut down. Whatever the propagandist element, a cult of martyrdom could only exist in certain conditions. In both these cases it was a grave misjudgement to dismember the body of the fallen commander. This was a vulgar act, in violation of the rules of war. The treatment of York’s dismembered head, adorned with a paper crown in mockery of his pretensions, inevitably extended the imagery of martyrdom through its unintentional evocation of Christ’s own crown of thorns.

In this form of remembering battle, the frightening portents seen before Evesham and Wakefield were recalled as evidence that a noble cause was to be betrayed, that something unnatural was about to happen. In the case of Simon de Montfort, a miracle cult grew up very soon after his death. While no such popular movement began after York’s death at Wakefield, his tragic fate did seem to hold a similar resonance within his own family. The most disturbing image, picked up in many contemporary accounts, and remembered with particular horror, was the mock coronation with a counterfeit crown. It suggests that the act of being crowned, and being seen to wear the crown, may have been a powerful yet painful symbol to York’s family. This allows us to return to Richard III’s crown-wearing at Bosworth with fresh insight. By publicly displaying and wearing the coronation crown of England before the first battle he ever commanded, Richard was not only emphasising the legitimacy of his own rule, but recasting the mocking ceremony visited on his dead father, and thus putting right a terrible wrong. Family honour was now restored.

Such a father-son motif was recently echoed in our own experience. George Bush Junior only entered American politics and later the presidential race after his father’s 1992 defeat, which had been widely perceived as an humiliation. This son too was the namesake of his father, and cast by the family in the role of heir, despite having more politically experienced siblings. And it is interesting to observe that in both cases, the anointed heir was the son bearing the closest physical resemblance to the wronged and humiliated father.

In the same way, many recent examples can be seen of the importance we all give to the dignified and appropriate burial of those close to us. In the Middle Ages, the ceremony of burial allowed an aristocratic family particular opportunity to express, through ritual, both the way it saw the deceased and the way it wished them to be seen. The elaborate protocol of these ceremonies offers us an intimate view of a family in the act of establishing its personal mythology. A hurried or undignified burial was an affront, and burial away from the heartland – the residences and religious establishments most closely associated with the family – always needed to be redressed.

The importance of this ritual undertaking is shown by the tremendous efforts made by Clarence’s kin to retrieve his body after Baugé. An extensive and risky search took place by night amongst the fallen of the battle so that the mortal remains could be returned to England for a suitably splendid funeral and interment. York’s body had been dismembered after Wakefield and the remnants were later hastily interred at nearby Pontefract. For the house of York, a reburial of their fallen champion was always intended and would clearly be of crucial significance. Even so, this ceremony was surprisingly delayed and when it eventually took place, in late July 1476, over fifteen years after the event, it owed much to the prompting of Richard, who had now reached young adulthood. Acting as chief mourner Richard led a seven-day procession from Pontefract to the family’s chief residence at Fotheringhay, where two days of ceremony took place, with no expense spared. This was very much the burial of a king who had never been crowned. An effigy was used, with the figure dressed in a gown of dark blue, the mourning colour of kings. The royal coat of arms was displayed without differencing, an heraldic indicator of the presence of an immediate member of the royal family, on the banner that accompanied the cortege. Most tellingly, a white angel held a crown behind the effigy’s head. The symbolism suggested an anointed one, rightfully receiving the coronation denied him by his enemies. Its prominence informed onlookers that this symbolism lay at the heart of the house of York’s identity.5

The epitaph, which would have adorned the tomb, spelled out York’s legend as his family wished it to be known. He was a rightful king, a prince who sought peace for the good of the realm, a ‘warrior of renown’ who defended the royal inheritance from its foes. Richard, as constable of the realm, would have had a personal input here, for the office of heralds, who recited this achievement, was now his responsibility. The words of the epitaph and the pomp of the reburial together animated the spirit of remembrance held at Clare. The images preserved of York, as dutiful statesman and destined king, now blossomed in a very public acknowledgement and commemoration. Its essence was distilled through displaying York as a flower of chivalry. This, the central motif of the Clare collection, found its epiphany at Fotheringhay.

Engraving of the seal of Richard, Duke of York, showing his shield with Falcon and Lion supporters, surrounded by other Yorkist badges, of Roses, Ostrich Feathers and Fetterlocks.

In an unusual and highly significant passage, the epitaph praised York’s martial skill at Pontoise, where in the summer of 1441 he put the French King and his army to ignominious flight. This courageous action inflicted a humiliating reverse on the French at the end of the Hundred Years War and the feat of arms was now extolled for the inspiration of future generations. At a time when morale was low and the tide of war had turned against the English, this success had stood as a beacon of pride.

York had been willing to confront the French King, Charles VII, in open combat. Charles was noted more for his timidity than boldness as a leader, and perhaps had never quite recovered from his experience as a young man on a royal visit when the floor gave way beneath him, sending the monarch and his entourage crashing through to the level beneath. York’s campaign in the Ile de France was carried out with notable audacity, relentlessly pursuing Charles and his army in a sequence of daring manoeuvres. These included surprise river crossings, night marches and the astonishing occasion when the French King was forced to decamp so quickly that York’s men found his bed still warm. For Charles it must have felt once again that the floorboards were giving way beneath him. His series of undignified flights made the French King a laughing stock in his own capital and revitalised the English war effort.

Historians have underestimated the duration and intensity of this campaign, which took place over a five-week period instead of the fortnight commonly ascribed. During its course, York displayed incisive leadership and personal dynamism, in contrast to the later perception that his generalship was desultory and lacking in conviction. Modern accounts have compressed the action, imagining York back at his base in Rouen by the end of July 1441, and as a result have missed the most important part of it, when he broke the siege of Pontoise a second time on 6 August.

York had already humiliated his rival, first offering him battle and then endeavouring to force it on him. Charles had fled back to Paris leaving most of his army behind. Now York swung back to confront his leaderless opponents, still encamped outside Pontoise. Contemporaries recognised this as the climax of the campaign and waited anxiously. Public processions were held in Rouen and prayers offered for the English commander’s safety. Although the French were numerically superior they retreated hastily, some seeking shelter in the makeshift siege works, others dispersing into the countryside. York re-entered Pontoise in triumph and spent over a week there, strengthening its defences and reinforcing its garrison. The vigour of his operation created despondency in Charles VII’s camp. One observer commented disparagingly that whenever the French King and his great men learned the direction the English army was taking, ‘they ran hard in the other direction’. The length of time spent by York on this dramatic escapade has a significance to which we will later return.6

The episode took pride of place in the epitaph, the cherished memorial set up by York’s family. It gave visible proof of prowess, the brave and honourable conduct of an unflinching warrior. It sprang from York’s own ideal of courage, a willingness to take risks, lead from the front and directly challenge those who opposed him. York expressed these sentiments in documents drawn up in the course of the campaign, emphasising how he had gone in person with all possible speed, to resist the ‘chief adversary of the realm’. York’s own father had been attainted for treason, for plotting against Henry V, and was deemed to have died a coward. It is clear from York’s conduct at Pontoise that he hoped to expunge the shameful memory of this through his own valour.

How might such ideas come across to others? A soldier’s story is revealing. During York’s term of office another English commander arrived with a large army. Rather than co-operate with the troops already in France he stayed aloof, with the pompous announcement that his plans needed to be kept absolutely secret. An opportunity to join forces and again challenge the French King was wasted. Instead the new army embarked upon a series of convoluted manoeuvres that left both friend and foe completely baffled. A sardonic joke arose amongst York’s captains stationed at Rouen. This general’s strategy had become such a secret, the tavern tale ran, that he was no longer able to ascertain his own intentions. The humour was certainly topical, for York had despatched a series of messengers, to be amply rewarded if they discovered where the meandering expedition had ended up. But it showed the comradeship of fighting men who knew their own leader would never act in such a fashion. York did not hide from the enemy and his soldiers respected him for that.7

York’s example may have been a touchstone for his son, as Richard prepared for his own confrontation with a rival at Bosworth. Shakespeare was right to depict Richard’s personal pursuit of his challenger, though the King was not to act alone but was accompanied by a body of cavalry that very nearly succeeded in cutting down Henry Tudor. All sources are agreed that Richard sought out his opponent on the field of battle, seeing the engagement not just as a clash of armies but as a duel between two champions. In this the son would rekindle the flame of his father’s memory and identify with his crowning martial achievement.

What has been set out is an attempt to understand the legend, the form of remembering adopted by one particular medieval family. I have used the epitaph as my key source, for I see it holding the force of York’s own words – showing how the triumph at Pontoise was so important to him – within a time capsule sealed by family recollection. The pride in the bold river crossings whereby he ‘put the King of France to flight’ is clearly evident. The commemoration of this exploit at Fotheringhay took place thirty-five years later. How was such a tradition kept alive? We must look to York’s wife, Cecily Neville, who accompanied him to France in the summer of 1441. After York’s death she became the chief custodian of the Clare collection and was an indomitable champion of its fortunes.

In this regard, one of Cecily’s letters is most revealing. She lobbies for the right to appoint officers within the religious community of Clare. If this is granted to her, she promises in return the benefits of her favour and patronage. This was a standard tactic employed by the great and good of the realm, though it tells us that Clare was certainly important to Cecily. However, what follows is both more personal and quite deliberately intimidating. If any person is not favourably disposed to her request, she asks for a full report of what they have said against it. Even if Cecily gets her way, she is prepared to persecute those who stood against her. Here we see a lady accustomed to power and ready to wield it to her advantage. This formidable woman had now emerged as chief protectress of York’s memory. In her letter she styles herself as widow of a rightful king of England, which as we have seen was the theme of the Duke of York’s commemoration, in which her youngest son played a prominent part. Cecily would have been only too willing to tell Richard about his father. Her role is crucial, and will be properly examined in the forthcoming chapters.8

I am not interested here in the intricacies of York’s military career or an overall assessment of his ability – although these are valid and important lines of inquiry in their own right – but how he perceived himself and was perceived within his family. If we can make a connection with this, I believe we can more fully comprehend the family’s motivation, particularly around York’s legacy and the issue of succession: what is being transmitted to the next generation and who will be its heir. This will be an exploration of family tradition, what it stands for, what it has achieved and what remains unfulfilled.

How ought such ideas be translated into a medieval context? In the Middle Ages the word achievement had a specific meaning, the adornment of a tomb with possessions of special value to the deceased. The family would group around the tomb on particular days of anniversary and remembrance. Its gathering would make a vital connection with a chosen source of identity, a mythology, and how it might unfold. This connection would be reinforced by the treasured artefacts held in collections such as that at Clare.

Individuals within the group would adopt roles in this family drama or story. The most prestigious but weighty role was that of heir and successor to the family legacy. The Bible was widely read in this period and the instruction of the Old Testament, which often hinged on the idea of birthright, a chosen one who would bring the family tradition forward, carried a real resonance. And here we need to distinguish between a custodian of that tradition, who held the family remembrance, and the one who enacted it. Normally the latter was the prerogative of the first male offspring. In the case of the house of York, I will argue that most unusually it became the guiding purpose of the youngest son. It will be this son, Richard, who most fully assimilates the story of his long-dead father and then attempts to fulfil his unfinished destiny. This painful legacy will be further defined. It will then be shown how Richard came to see himself as his father’s true successor. Once this is established, I will portray the culmination of Richard’s unfolding sense of mission, the ritual preparation and plan of battle he chose to enact at Bosworth Field.

This is a path on which we must proceed cautiously. The whole meaning of Richard’s actions could be known only to him, and there is too great a gulf between his time and ours to be sure we understand the full range of his motives. Nevertheless we can get a sense of the inner lives of Richard and his father from their surviving books of hours. These were guides for personal devotion, commonly owned by the wealthy, in an age where outward religious formality was of far greater importance than our own. But in the case of Richard and his father, the books of hours contained personal additions, prayers chosen and collected for their own use that suggested a very real piety. In other words, both men shared a private devotional outlook as well as being prominent players in the expected arena of public observance.

Such an interplay of private belief and public action also extended to the arena of war. Before embarking on his expedition to Pontoise, York visited Rouen Cathedral, where he knelt solemnly before the main entrance with two bishops at his side, before being escorted alone to view the holy relics uncovered at his request. This personal pilgrimage, undertaken entirely of his own volition, was a precursor to risking his life on campaign and tells us that the ritual of preparation was as important for him as the military event itself. His son Richard, sharing his deep personal piety, might well have invested similar importance in his own religious preparation before the life or death struggle at Bosworth. The ceremony of wearing the crown of England would have been preceded by a solemn vigil and the careful observation of communion. The personal prayers gathered by father and son suggest both had a strong sense of religious duty as well as personal destiny – they would have thought about how they acted.9

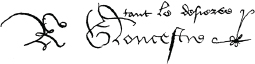

Yearning for a noble cause: signature of Richard, as Duke of Gloucester, with one of his mottoes ‘tant le desieree’ (‘I have longed for it so much’) at the bottom of a page of his manuscript copy of ‘Ipomedon’, the story of ‘the best knight in the world’.

A capacity for reflection, for thinking about and trying to make sense of events, is brought out by Richard’s book collection. Richard owned a modest personal library, whose subject matter ranged from chivalric romance and history to prophecy and religion. It also included treatises on the way a nobleman should properly conduct himself in public affairs. Owning books, then as now, is not necessarily proof of active thought or imagination. Just as we might leave an expensive book on the coffee table for show, in the late Middle Ages books and manuscripts were status symbols, and deluxe versions were amongst the expected finery surrounding an aristocrat, part of his ‘magnificence’, the goods and possessions that reflected the greatness of his position. But Richard stands a little apart in often putting his signature, and sometimes an accompanying phrase, in his books, an indicator not only that he read them but also that he valued them highly and thought about their contents.

Given this, we can assume Richard was familiar with the chief manuscript work compiled for his father at the family centre of learning at Clare. This was a translation of part of Claudian’s life of Stilicho, praising the moral qualities and achievements of a great general of the late Roman empire. It was personally dedicated to York and intended as applicable to his political career. The translator likened Stilicho’s stoicism to York’s own restraint under provocation. In a topical allusion, Stilicho’s journey to Rome to receive the consulship was paralleled with York’s return to parliament to request renewal of military office in France. The manuscript occupied a central place in the Clare canon, attractively decorated with the badges of the house of York.

Because of its close association with his father, and the relevance of its subject matter, soldierly qualities with which Richard strongly identified, he may have looked to this text at times of crisis in his own life. It was designed to be accessible, with the Latin original and English translation on facing pages and the English rendered into verse, making it easily readable. For Richard sections of the work were strikingly apt. While Stilicho was serving in the Roman province of Britain, he was praised for defending the boundary with Scotland and resisting enemies in northern France. Richard, in the reign of his brother Edward IV, took command of the Scottish border with vigour – launching expeditions deep into enemy territory. He was also an advocate of resumption of war with France and publicly disapproved of the peace treaty agreed between the two sides. The epithet on Stilicho, ‘...through his helpe... I should not fere bataille, ne of Scotland, ne of Picardy’, would have struck a chord. Inevitably in a subjective exploration parallels can only be taken so far. But the possibility of Richard, through his reverence for his father, modelling himself on Stilicho, needs to be considered.10

The flattering comparison with Stilicho pointed up the other martial tributes amassed in York’s memory: the epitaph, recalling his prowess at Pontoise, and the Clare scroll, with its praise of his war triumphs. Together they evoked a commander of talent and energy in highly eulogistic fashion. A broader idea is carried through. Stilicho’s political desires, including the union of eastern and western portions of the Roman empire, are seen as noble and also as legitimate, having been promised him by the Roman Emperor Theodosius, whom he had loyally served. Idealising such a figure, alongside the cult of Richard’s father, might entail drinking from a poisoned chalice. Stilicho’s aims are undermined by the machinations of others, a dimension that occurs frequently in the perceptions of York and his youngest son. York’s wish to renew his command in France was frustrated, in his eyes at least, by a jealous court party. Some thirty-five years later Richard’s campaign in Scotland was strongly criticised by a faction within the court of his brother, Edward IV. Claudian’s portrayal of Stilicho fitted well, with its contrast between a valiant commander, fighting to defend the frontier, and corrupt and effete court politics.

But Claudian’s emphasis of Stilicho’s personal qualities and nobility of purpose, amidst the scheming of his opponents, created a highly ambiguous morality, again echoed in the violent careers of York and Richard. When Stilicho plotted the brutal murder of his rival, Rufinus, Claudian applauded the act as necessary and desirable. A man who lived by the sword might well die by it. Despite his war triumphs, Stilicho was finally betrayed and executed. The tenor of violence in his life and death carried its own warning.

Our consideration of how Richard viewed his father gives us an interpretative key to a different understanding of his outlook. To make this tangible we will now look at the means by which this youngest son came to regard himself as heir and successor by right. This will involve looking at the individual characters and personalities of the ruling dynasty, and at the scandalous secret rooted in this generation of the house of York. It’s time to meet the family.