On 20 August 1485 the Yorkshire squire Robert Morton drew up his will. Like many other men about to go to war, he made careful provision for his family. But the preface to the document contains a remarkable statement of intent. Morton was ‘going to maintain our most excellent King Richard III against the rebellion raised against him in this land’.1 Although only a fragment of Morton’s will survives, it was probably made at Leicester, the final assembly point for Richard’s gathering army. Troops ready to fight against Tudor congregated here on the day Morton penned his emphatic declaration of loyalty to Richard III. On the morning of 21 August the army moved out of the town in full pomp, its war banners unfurled. The die was cast.

As Morton set his affairs in order he would have looked to the imminent battle in which his life would be at stake. The mustering place of an army would see hundreds of soldiers pausing to make provision for their goods and lands and consider the journey of their soul. This was a poignant moment of reflection in the face of a gathering storm. The records of the French town of Châteaudun give a moving snapshot of a fifteenth-century army readying itself for a decisive encounter with the enemy. Arrangements were made for the fate of valued possessions and requests placed with religious houses for prayers and intercessions should the life of the supplicant be lost.2 Men understood when the moment of truth had come.

Richard had left his mother Cecily’s home at Berkhamsted towards the end of May and spent two months in the Midlands, at Nottingham Castle, his principal military base and one of his favourite residences. From this central location he would be able to move swiftly once the direction of Tudor’s advance became clear. Then on 11 August came the news that Tudor had landed in South Wales. The King wrote to a potential supporter with energy and determination of his wish to personally confront his challenger at the earliest opportunity.3 Richard was eager for a decisive battle and a victory that would confirm his right to rule.

The country was not big enough for two kings and it is important to remember that Richard was facing an opponent who had directly and unequivocally laid claim to his office. The step Tudor had taken was in late medieval terms unprecedented, but it would be stranger still if Richard failed to react to it at once. Had he hesitated he would have appeared to concede. His purposeful readiness, therefore, was not nervous and precipitate but wise and necessary.

Significantly, this was not the first time a rival king had been faced down by a member of the house of York. In France forty-four years earlier Richard’s father had been lieutenant and representative of Henry VI, who counted himself also as king of France. King Charles VII thought differently, and the confrontation that took place at Pontoise was between two rival claims to the same realm. As we have seen, the French King fled ignominiously, and this weakened his royal credibility. Pontoise was only the second occasion Charles VII had risked leading an army against the English, and on the first, at Montereau-sur-Yonne, four years earlier, York had also wished to challenge him personally.4 The precedent was clear – and Richard followed it without hesitation.

We will never know the exact size of the army Richard gathered at Leicester. We do know that it was a substantial force that outnumbered Tudor’s. Just as for his father, speed and decisiveness were indicators of self-belief, and thus more important than waiting to gather overwhelming superiority of numbers.5 Another king, opposed by a challenger already within his realm and claiming his title, has been criticised for his urgent reaction when delay might have offered advantages. But King Harold marched swiftly to meet the invasion of William the Conqueror, and although it is easy to fault his strategy with the advantage of hindsight, at the time the presence of the rival and his claim could not be tolerated. The longer William was allowed to remain unmolested, the greater both his confidence and his credibility would become.

A less discussed but more pertinent issue is the manner in which Richard intended to fight this all-important battle. The way one fought was important to medieval society and one encounter in particular held an enduring fascination, the climactic battle on the plain of Troy between the Greeks and the Trojans. This distant martial episode became something of a late medieval best-seller, translated into numerous languages, with its manuscript histories beautifully produced and illustrated. The word ‘history’ was very much a contemporary euphemism, for these deeds of arms had long passed into the mists of mythic imagination. What was important was not whether they had actually happened but the effect they evoked in their audience.

The clash of arms outside Troy was a roll-call of honour. Enormous care was taken in listing those present on both sides, the captains of renown and their achievements, a form of description also used by heralds in their relation of medieval battles. The skill lay in creating and building atmosphere in the narration. Time and movement are quietened, instilling a sense that all eyes are watching the assembling armies. The massing onlookers gather on the Trojan ramparts. All are to be witnesses to an extraordinary dramatic spectacle. Perception is then intensified through the capture of significant detail: the vivid colouring of a shield hanging from the wall, a flash of sunlight on burnished armour. And in the last moments before the armies engage, language is stilled. The power of the battle will be drawn from the silence that precedes it. What follows is an exhilarating cacophony of sound: the guttural roar from the combatants as the lines suddenly surge forward; the crashing din of impact as bodies collide and blows are exchanged. The best medieval accounts of battle understood this truth. They forego the analysis and explanation of which we are so fond, and employ rhyme and alliteration to imitate the terrible noise of war.

This is a compelling yet terrifying arena. Humanity is brought to it through individual deeds of valour that are recalled and commemorated, how men conducted themselves in a struggle for life or death. The best and the worst are related, the moments of incredible courage, the moments of cowardice and dishonour. Here will be the inspirational act that will push an army forward and give it fresh reserves of strength. But here also will be the betrayal that will undermine its resolve and corrode its unity. Lessons will be learned for the future. The Trojan Hector fought with amazing tenacity and none could withstand his onslaught. But in a moment of greed he turned to plunder the rich helmet of a fallen opponent. It was this lapse of concentration which allowed the Greek champion Achilles to slay him.

The continuing popularity of the Trojan War in medieval times tells us that people cared as much about how battles were fought as about their eventual outcome. Richard would have been no exception. His courage at Barnet, the first battle in which he ever fought, led a contemporary poet to acclaim him as another Hector. Richard owned his own annotated history of Troy. The book related in full the epic war against the Greeks that culminated in the city’s tragic destruction. Richard’s signature as King was prominently placed above the first page of the text.6 So it is worth asking how he might have imagined this forthcoming encounter. Such a subjective question always has to be put with caution, for we have no direct way of knowing how Richard thought. Yet the evidence already rehearsed on his character and outlook suggests that he would have carefully considered his plan of battle. We will now go a step further, and look at one particular battle that may have held such personal meaning for Richard that he modelled his own on it.

Medieval commanders sometimes looked to earlier battles as a source of inspiration. Sir John Fastolf, writing at the end of the Hundred Years War on the future shape of war strategy, drew on the example of the decisive English victory against considerable odds at Verneuil. The turnaround of fortune there was seen both as a tribute to the courage of the troops and as proof of God’s support for a just cause. However difficult a present situation was, this previous battle remained a sign of encouragement and hope.

For Richard, such an example might have been a battle outside his own experience and tradition but which clearly mirrored his own circumstances. The battle of Toro was fought on 1 March 1476 to determine royal succession within the kingdom of Castile. The forces of Queen Isabella and her husband Ferdinand were opposed by a coalition of rebels and their Portuguese allies who did not accept her claim to the throne. She had succeeded her half-brother, who had died two years earlier, by declaring that his daughter was in fact a bastard. For Richard the parallel was obvious. Some had accepted Isabella’s title, some had not, but it took this decisive victory to confirm it. Isabella’s military triumph had made her position secure.

Richard would have further identified with Isabella’s devout piety and crusading zeal. Her desire to launch a crusade against Moslem Granada became attainable through success in this battle. By the time of Richard’s accession war had been opened on the frontier of Granada and a number of victories gained, the only instance in Christendom of the active engagement Richard admired and longed for. Toro had been the gateway for this achievement.

The battle was celebrated not only for its decisive outcome but the manner in which this was realised. Isabella’s husband, Ferdinand, ordered a direct charge of heavily armoured knights against the main position of his opponents. He broke their strength in little under two hours, and his use of cavalry in this way was seen as the epitome of chivalric valour. Ferdinand had taken the fight to the enemy.

The house of York had a keen interest in Castilian affairs, based on their own blood-link and possible right to the throne, which Richard’s father had earlier investigated. The Castilian connection was marked in genealogies and chronicles commissioned for the family. The claim had lapsed but the sense of connection remained, and the marriage alliance mooted between Edward IV and Princess Isabella in the early 1460s was an expression of this. Edward’s choice of an English bride had alienated Isabella and it is significant that her reconciliation was offered to Richard on his becoming King, when she confided that Edward IV’s behaviour had turned her heart from him.

Isabella’s triumph over her opponents and subsequent crusading success would have had considerable impact on Richard. The manner of its achievement was likely to make a lasting impression. Bosworth offered the King a chance to emulate it through a comparable feat of arms. His letter of 11 August 1485 to a potential supporter specifically requested that he come horsed, that is, that he bring mounts suitable both for riding and battle. This indicates that deployment of cavalry against his opponent was very much in his mind, and that it formed part of a carefully prepared strategy for the battle.

Aware of this, it is intriguing that the only foreigner of note in Richard’s army was a subject of Ferdinand and Isabella, the experienced Spanish war captain Juan de Salaçar. He was at Bosworth on Richard’s invitation and given a prominent place in the royal division. He may also have helped shape the King’s battle plan. Richard chose to have Salaçar close by him, and spoke with him as the engagement unfolded. The Spaniard later gave an account of the King’s preparation of the cavalry charge, which found its way into a newsletter on the battle sent to Ferdinand and Isabella. His presence in a completely English army would have been most noticeable. Richard’s employment of Salaçar provided a ritual link with the earlier battle and a source of advice on the timing of a heavy cavalry action.7

Toro established the legitimacy of Isabella’s rule. Richard approached Bosworth hoping to achieve the same. As he rode out of Leicester he was seen to be wearing a crown, the tangible symbol of his legitimate right to rule. A ceremonial crown would have been too cumbersome to display in this fashion, so at this stage, advancing rapidly with the soldiers, he is likely to have worn a gold circlet specially welded to his helmet. There is good evidence that he also wore this during the actual fighting.

Riding in formal array with banners unfurled provided the setting for a kind of pageant, where Richard could communicate his beliefs to his men. The language of costume and procession is powerfully effective and can reach people in a real and immediate way, which speech-making alone could not achieve. Some ritual preparation had been used in stirring fashion before the English victory at Verneuil, when the commander used a pageant and symbolic costume to infuse the entire army with his beliefs. His soldiers understood and got the message.

Richard also felt the importance of clear communication to his followers. For this reason he had had his coronation oath translated into English, and cited it at important moments during his reign. As his army readied itself for battle, it was a crucial time for men to see and understand the cause in which he led them. That cause was the legitimate succession of the house of York.

This was leadership from the front and it carried its own risks. To lead a cavalry charge against the enemy was daring but dangerous. Richard’s namesake, Richard I, had launched such an attack at Gisors to great effect, but subsequently admitted that everyone had advised him not to attempt it because of the likelihood that he would be killed. Indeed, the conspicuous garb of kingship did make its wearer a most visible target. At Agincourt Henry V had also chosen to wear a circlet crown fixed to his helmet. It inspired his men, but led to him being surrounded by many knights seeking to slay him. They came close enough to knock out some the jewels on the crown itself. By choosing to emulate this form of heroic leadership, Richard was embracing its opportunities but also its dangers.

Launching a substantial mounted attack also carried tactical risks within the shape of the battle. Such a dramatic move would have to be made spontaneously when the occasion presented itself, and once it was launched the overall cohesion of the army would be hard to maintain. The sheer speed of a cavalry charge would make it difficult for the infantry behind them to advance and back them up. Cavalry had been little used during the Wars of the Roses but on one earlier occasion, at the battle of Towton, just this situation had arisen and the Lancastrian side had been defeated when their infantry was unable to follow in support of a mounted charge. Once Richard had committed his forces to it, the manoeuvre would isolate him from his other units and if unsuccessful, would leave him exposed and vulnerable. This alerts us that a new and very different reading of the battle is possible. The failure of infantry to engage does not necessarily constitute a betrayal.

It had taken Tudor two weeks to march from South Wales to this part of the Midlands. Before he lost his only two Yorkist peers as hostages his intention was probably to land in the West Country, where both commanded support. A landing at Milford Haven instead presented real difficulties. Support for Richard in South Wales prevented Henry taking the coastal route into England and a royalist garrison at Harlech barred the north. He was therefore forced to advance through mid-Wales and cross into England at Shrewsbury. In letters sent out in an attempt to gather support he continued to style himself as king but significantly dropped all reference to his claim through lineal descent, conscious as he must have been that this Lancastrian emphasis would undermine his chances. The numbers that joined him there were still relatively small. A few more came to him after he crossed into England. The undertaking looked highly doubtful.

On 20 August Tudor did not take to the road with his troops but stayed behind with a small bodyguard. Observers detected more than a hint of melancholy in his demeanour. On setting out later in the day to catch up he became completely lost. By nightfall he had still not re-appeared and his supporters had no idea of his whereabouts. The self-styled king of England rode into the camp the following morning with some explaining to do. He announced with commendable sang-froid that more adherents had been located and would be joining them shortly. Whether or not they ever did so is unknown. Beneath the black comedy of this episode there is a distinct sense that things were on the verge of falling apart. One sign that Henry’s confidence was fading was a decision to leave his uncle Jasper Tudor behind him to safeguard a possible escape route. For no contemporary source mentions Jasper’s presence at the battle, and this can be the only explanation.8

Tudor’s last hope lay with the Stanley family. As husband to his mother, Margaret Beaufort, Thomas, Lord Stanley was his stepfather and thus a seemingly likely ally. But during the rebellion of 1483 Stanley had remained loyal to the King, and Richard trusted him enough to commit Margaret to his keeping, despite her plotting on behalf of her son. This demonstrates once again that pragmatic thinking and the calculation of a family’s tactics for advancement was done in a manner that set aside all sentiment. Stanley’s record in avoiding all the significant battles of the Wars of the Roses was second to none, and his eldest son was kept as hostage in Richard’s camp. The most likely member of the family to take positive steps in Tudor’s support was Stanley’s younger brother Sir William, but following a tense meeting at Atherstone in Warwickshire on 21 August neither man committed himself directly. Although Sir William Stanley was by this stage suspected by Richard of treason and might therefore be expected to side against him, he did not commit himself overtly to Henry’s cause. This was a sign of how bleak things now looked. The Stanleys must have concluded that Tudor’s chances were not good, and thus they kept independent control of their forces.

A crafty survival strategy for the family seems to have been operating. If Henry were overwhelmed at Bosworth, Lord Stanley would claim his inaction as loyalty to Richard. Even if Sir William appeared at the battlefield, if he kept separate from both armies it could be said that no treason had been committed. The extraordinary juggling act was to complicate the forthcoming battle. But the fact that Stanley forces failed to join Tudor was a considerable blow to him.

The prevarication of the Stanleys shows us how difficult it is to interpret Bosworth simply on moral grounds, as a judgement on Richard as man and as King. The realities of fifteenth-century politics were hard and complex and the way men acted could be determined as much by motives of self-interest, their own ambition, greed and pride, as by higher principles of loyalty, allegiance and moral concern. The heart of Stanley identity lay in the localities, the region of North Wales, Cheshire and Lancashire where they were regarded as ‘kings’ of their own principality. The family was shrewd enough to protect and further its interests at court. But the matter that touched its sensibility most in the Wars of the Roses was not the vicissitudes of national politics but a vicious local feud with the rival Harrington family. This long-running dispute was a struggle for dominion in northern Lancashire, and the Stanleys were determined to win it. Here Richard played an important part, and one that left the Stanleys with an abiding suspicion of him. It may have been this, rather than the merits of the rival claimants, or loyalty to a stepson, that finally determined the way this self-interested family chose to act on the battlefield.

We can read of the battles and marches, changes of regime and dramatic turns of fortune, that characterise narratives of the Wars of the Roses. Underneath lay an ugly, yet durable layer of human behaviour, the brutal struggle for power in the provinces. Such rivalries flourished when royal government was weak or unstable. Then scores could be settled with impunity. A king presiding over his court at Westminster might be a distant notion to many, but local hegemony, the possession of castles, lands and status, really counted for something. And Stanley sights were fixed on a particular castle, that of Hornby in northern Lancashire. It was an impressive fortress, with its great gates, battlements and keep set high above the confluence of two rivers, dominating the great north road from Lancaster to Carlisle. It belonged to the Harringtons.

The Harringtons were a prosperous gentry family who had suffered their own disaster at the battle of Wakefield, for they had been key members of the army led by Richard’s father, the Duke of York. The head of the family was killed in the action; his eldest son John died of his wounds the next day. This calamity left part of the family inheritance vulnerable, for by the terms of landed title, Hornby was then to pass to John’s young daughters as heiresses of the estate. This gave the Stanleys a chance to intervene. In quite predatory fashion they used their influence at court to gain control of the girls. They then carried them off and forcibly married them, one to their own kin, another to a chief supporter. This gave them a right to the Harrington lands at Hornby. Their behaviour should remind us that Richard III held no monopoly of ruthlessness in pursuit of family inheritance. The Stanleys pulled together in this unsavoury act of aggrandisement, and it was Sir William who played a crucial role, locking the young women up in the remote fortress of Holt in North Wales to prevent the Harringtons rescuing them from their clutches.

The remaining Harringtons refused to kowtow to the Stanleys. John’s younger brothers stuffed Hornby Castle with provisions and military equipment and refused them admission to the estate. The result was a full-scale siege. Hornby was put under a massive artillery bombardment, the Stanleys bringing one great cannon all the way up from Bristol. The Harringtons still held out. It was a desperate rear-guard action.

Edward IV seems to have taken a pragmatic approach to the dispute. He relied on the Stanleys in the north-west and did not want to jeopardise their support. A succession of royal commissioners therefore endeavoured to secure a hand-over of the property. But while King Edward was prepared to acquiesce to Stanley ambition and greed, Richard’s response was very different. In defiance of his brother’s wishes he wholeheartedly backed the Harrington family, at considerable risk to himself. At the height of the fighting, in the early 1470s, he on one occasion actually joined the Harringtons in Hornby Castle, and his men engaged in a number of skirmishes with Stanley followers.

This course of action appears decidedly against Richard’s own interests. If we imagine him solely as acquisitive and unprincipled, he would be more likely to ally himself with Stanley influence and continue to build up his own power in north-eastern England. If we see him as a loyal lieutenant of Edward IV, he would accept his brother’s broader policy, the delegation of authority to chosen aristocrats. Instead he championed a family of minor influence and standing. The Harringtons were only able to hold out for so long because of his protection. A settlement was finally brokered before the French expedition of 1475 and Richard seems to have done all he could for them. Although they were forced to surrender Hornby to the Stanleys, their other Lancashire possessions were safeguarded. King Edward had agreed to take on the burden of making a final agreement stick, but it was Richard who was active behind the scenes. A property exchange between him and Sir William Stanley, allowing the Stanleys to strengthen their position in North Wales, may have been a key reason why a deal was at last secured.

Richard’s actions on behalf of the Harrington family were extraordinary and forged strong bonds of friendship. He took both younger Harrington brothers into his service, where they were amply rewarded. Both served with distinction on his 1482 expedition to Scotland. Richard’s generous patronage was reciprocated with unswerving loyalty. The Stanleys might keep their own counsel about where and with whom they would fight at Bosworth. The Harringtons gathered under Richard’s banner.

There is only one likely explanation for Richard’s conduct. The Harringtons had been steadfast in their loyalty to his father and the head of their family and his heir had fought and died for his cause. It was inconceivable that they should now suffer for it. Richard clearly identified with their plight. He seems to have regarded the protection of their interests as a debt of honour that he would repay as far as he was able. In this we once more see him acting as York’s heir and successor. Early in 1485 there were rumours that he was prepared to reconsider the award, which had dispossessed the Harringtons, and return Hornby to them. He may have seen this as the righting of a terrible wrong. But it antagonised the Stanleys, who had been prepared to back him in the autumn rebellion of 1483. However cautious their strategy, at Bosworth Richard was faced with the real danger that the sizeable retinue commanded by Sir William Stanley would intervene against him on the battlefield. Were this to happen, his reverence for his father’s memory would have cost him dear. It is a supreme irony that a Stanley betrayal at Bosworth might be prompted not by the worst and most ruthless act Richard ever committed, but by the best and most courageous.9

It is now time to consider where the two armies actually met. Some understanding of the battle’s location, as far as it can possibly be known, is necessary to make sense of what happened there. This may seem a largely self-evident exercise, for shouldn’t the name of a battle give a clear indication of its location? This would certainly be a modern expectation, along with the wish to define a battle site as exactly as possible: setting out its terrain and the relative position of the armies, providing the maps and diagrams that adorn the pages of our text books. But this was not the same priority for medieval writers, and their process of naming tells us something important about Bosworth. What was being commemorated was not where the battle was fought but the place where the dead were buried afterwards. And a burial site could be many miles distant from the actual battlefield.10

In the aftermath of battle the field was strewn with carnage. Physicians and surgeons might attend to some of the seriously wounded. But the bodies of the dead needed to be gathered. This allowed a tally to be made of the casualties, the nobility and gentry, who were identified through their coats of arms and listed individually and the ordinary rank-and-file, who would be heaped in piles so that a rough guess might be made of the numbers slain. The grisly task was supervised by the heralds. Then the bodies needed to be buried. Many were unceremoniously dumped in mass graves. But others were moved to consecrated ground, lands belonging to a church or chapel in the vicinity or on the army’s subsequent line of march. This would have formed a grim spectacle. Carts would have been loaded with bodies, some hacked to pieces and unrecognisable, an arm here, a leg there. Cauldrons would be set up on the battlefield to boil off flesh from the bodies, for bones could be transported more easily and hygienically. And even the bones would carry the signature of war, cracked skulls and forearms split asunder in the ferocity of combat.

But however smashed and broken the physical remains, medieval people were deeply concerned about the fate of each combatant’s soul. Church wall-paintings showed souls suspended in purgatory, desperately appealing for intercession. These gave a stark reminder, conjured by the De Profundis, the psalm for the dead, sometimes recited on a daily basis alongside a memorial or tomb: ‘...out of the depths I have cried for thee... my soul does wait... more than they that wait for the morning’. To free the souls of the many killed in battle required a form of religious commemoration, proper Christian burial and remembrance in prayers and divine service. This intercession could then be held in recorded memory through the battle name.

This medieval way of seeing battle, however odd or unusual to us, fulfilled a vital function in an age preoccupied by the suddenness with which death could strike. At Bosworth the bones and remains of the dead were carried to a small church at Dadlington, where they were buried and later commemorated through the establishment of a chantry dedicated to the slain, a fact used to justify a fund-raising appeal for necessary improvements in the early sixteenth century. This was set in motion in 1511, early in the reign of Henry VIII, in remembrance of ‘the soules of alle suche persons as were slayn’, recognising that bodies of the fallen combatants were brought to the church and then buried within its boundaries. How might one give directions to a mass burial ground? A striking physical feature might be recalled, such as Redemore – the area of wetland that surrounded the burial site. A tug-of-war developed between the competing claims of the small village community of Dadlington, where the dead were laid to rest, and the nearest small town that might act as a landmark, that of Market Bosworth. It was the name of Bosworth that stuck, and by the 1530s was being used consistently in relation to the battle, as it still is today.11

That was sufficient in the immediate aftermath. While battlefield tours were not unknown in the Middle Ages, they were confined to the occasional visits of war veterans. It was the success of Shakespeare’s play that stimulated a far larger interest. The drama was so gripping that people actually wanted to come and see for themselves where Richard cried out for his horse. In response to this, at the end of the sixteenth century local historians tried hard to ascertain the battle’s exact location. The result was an uneasy hotchpotch of rumour and folklore. It would have seemed as logical to them as it would be us to place the fighting near the resting place of the slain. Since little topographical information existed, logic might also suggest a prominent nearby hill, a mile or so to the north, as the place a royal army might have camped and fought. The first mention of Richard and Ambion Hill is found in Raphael Holinshed’s chronicle. This source drew on local knowledge, but it came out in 1577, nearly a hundred years after the battle. Yet a battle tradition quickly developed. Early seventeenth-century maps of Leicestershire designated with sudden confidence the site of the encounter – ‘King Richard’s Field’ – in close proximity to the hill. The county historian William Burton, whose researches on the folklore of the battle retain considerable influence, put Richard and his whole army on Ambion Hill the night before the engagement. There is a worrying lack of contemporary evidence for this location. Local hearsay put Richard on Ambion Hill, and there he has remained ever since. Once the position of the King was accepted, it followed that Tudor would approach Ambion Hill from the west. In this version the forces of the Stanleys, so crucial to later events, cannot be located precisely but must have been somewhere nearby.

Further developments were in store. Once the eighteenth-century antiquary William Hutton had visited the site and devoted a book to it, its part in the battle developed a wonderful fixity. Now Richard not only camped on Ambion Hill, but also fought from its heights the following morning, a tradition maintained today by the white boar banner, the emblem of Richard, and trail markers of the battlefield visitor centre. A narrative drawn from scanty evidence has gained respectability through the passage of time. Very recently an adjustment was made, which shifted the crux of the fighting a mile further south and placed it near the burial site at Dadlington. This at least removes the action from the hill but tinkers with, rather than seriously alters, the established scenario.

Our sentimental attachment to Ambion Hill must now be severed for good. For a number of important reasons, the traditional battle site just does not work. Evidence for it was always thin, and the few near-contemporary references to the fighting, previously disparaged, contradict it entirely. Most crucially, the best near-contemporary source refers to a flanking manoeuvre made by Henry Tudor’s men on the morning of the battle to gain the advantage of the strong August sun behind them. This important information was gleaned by the Tudor court historian Polydore Vergil from those who had fought with Henry. It would have Tudor’s army advancing on Richard from the south-east, a possibility so inconvenient that it has simply been set aside. But suppose that instead of disregarding this key detail, we look for a scenario that might make it possible.

There is a strong case for putting Richard’s army on an entirely different site, eight miles to the west, on the northern outskirts of the small market town of Atherstone. This new location is supported by place-name evidence. We can choose between the more decorous ‘Royal Meadow’, the name of a field just north of the town, or the splendidly down-to-earth ‘King Dick’s Hole’, at the confluence of two rivers close by. Medieval epithets carried their own rough humour but we are likely to bring more to this robustly descriptive name than locals would have intended. This colloquial tag is the remembrance that Richard’s army camped there and that the nearby ground was marshy. Interestingly, Polydore Vergil’s description notes the marshy terrain between the two armies.12

It is also likely that Henry Tudor and his army spent the night before the battle at Merevale Abbey, a mile to the south-west of Atherstone. Tudor had been in the vicinity all day in a fruitless attempt to persuade the Stanley contingent, stationed in Atherstone itself, to join his forces. Henry later paid compensation for damage to the fabric of the Abbey, caused by his men lodged there. In order to challenge Richard on Ambion Hill, Tudor needs to have left the town the evening before the battle and headed rapidly east. Those who placed the battle in this direction claim a source for a local guide who took Henry into the open plain as night fell. This story, however, appeared more than a hundred years after the event.

But if Richard were just north of Atherstone and Tudor to the south of it, everything is different. One of our earliest sources refers to Richard’s having camped close to Merevale Abbey, ready to meet Tudor’s challenge, and names their clash the following day as the battle of Merevale. This is the Crowland chronicle, which gives valuable information on the progress of Richard’s army from Leicester and the ritual employed by the King, almost certainly derived from men who fought with him. Another, the Warwickshire antiquarian John Rous, places it on the Warwickshire-Leicestershire border, which is exactly where Atherstone lies. We might expect Rous, whose account includes a vivid description of Richard’s last moments, to be well-informed on such a significant detail, given his own interest in the county of Warwick. And the newsletter despatched to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain describes the major town nearest the battlefield as Coventry not Leicester, again putting the site further west.

Even more striking are two documents detailing compensation subsequently paid by Henry for crops trampled by his army as it marched to battle. Two separate payments are made, one reimbursing Merevale, whose lands were on the route to battle, the other, even more tellingly, to those who owned land on the battlefield itself. In making this payment Henry seems to delineate a field of combat, stating that fighting took place in the parishes immediately to the east of Atherstone. This all-important reference has been underestimated. Although both documents are in print, they need to be read together to make clear the precision with which Henry is referring to the site of the battle. In the first of these, Tudor compensates Merevale for crops damaged by his army, ‘our people coming toward our late field’, that is marching towards the field of combat. In the second, he details monies to be paid out within Atherstone itself, and the neighbouring villages of Mancetter, Witherley, Atterton and Fenny Drayton, for destruction caused ‘at our late victorious field’, that is during the course of the battle. These grants were made on 29 November and 7 December 1485, within months of the fighting.13

A strong impression is made that Tudor’s grant defines an encounter amongst the open fields east of Atherstone. It is reinforced by a later petition to the King from the Abbot of Merevale. In September 1503 Henry had returned to Merevale and given money for stained glass to celebrate his victory. This still survives. It suggests Merevale’s proximity to the actual battle site, something the Crowland chronicler emphasised, and will be fully discussed in the subsequent chapter. Capitalising on this act of royal goodwill, the Abbot made an opportunistic plea for the whole of the lordship of Atherstone. The right to this was held by another religious house, the Carthusian priory of Mount Grace. Early in Henry VII’s reign its possession had been contested by King’s College, Cambridge, without any final settlement being made. Now the Abbot of Merevale threw his own hat into the ring. Having no effective claim to speak of, he made a blatant appeal to sentiment. The Abbot reminded the King that if he made over the lordship of Atherstone to Merevale, it could form an everlasting memorial to his triumph. This allowed for a close link between Merevale and the battle. It also implied that the actual battle site lay within the lordship of Atherstone and that by incorporating it within Merevale’s bounds the encounter would be properly commemorated. The wording is quite deliberate. If Henry makes this grant, the lands shall be held ‘in parfaite and perpetual remembraunce of youre late victorious felde and journey, at the reverence of God’. There would be little point in such a plea if the battle took place in an entirely different location.14

We must remember that this is the only known occasion Tudor paid out compensation as his army advanced. There must have been many moments on the march through Wales and England when crops were seized or damaged. Yet there is no evidence of any other act of restitution being made. So this seems to be a special, symbolic gesture. It may have arisen out of Henry’s gratitude to God for the means by which he had been granted such an extraordinary victory. By tracing the direction of the army as it fanned out across the fields, thereby trampling the crops, we find at last an explanation for the all-important flanking manoeuvre. Henry marched east out of Merevale, through the Abbey’s fields, then swung northwards. Thus his men were able to advance with the sun directly behind them as they closed on Richard’s army. Such an advance places the Stanleys, in Atherstone itself, mid-way between the two forces, a distinctive feature also described in Polydore Vergil’s account. By his careful allocation of money, Tudor gave thanks for the gaining of a vital tactical advantage before the fighting commenced.

One of the men chosen to hand out this cash payment was John Fox, the parson of the small village of Witherley, east of Atherstone. Henry also made an additional grant to this community. The flanking march may have culminated with Tudor lining his men up in Witherley’s open fields. He would now be facing Richard from the south-east, with the sun behind his back. Battle would be imminent. A manuscript lists knights created by Henry before Bosworth. New knights were dubbed on the eve of battle or on the actual field of combat, in the lull before the fighting started, to inspire an army to acts of courage. Medieval romance literature put it well: ‘He who has a right to the title of knighthood has proved himself in arms and thereby won the praise of men. Seek therefore this day to do deeds that will deserve to be remembered’.15

The alternative battle site proposed here stretches out across the plain east of Atherstone, from the confluence of the rivers Anker and Sence, above which Richard’s army had gathered, past the small villages of Mancetter and Witherley, where Tudor’s army swung northward to confront him, to the outlying hamlets of Atterton and Fenny Drayton, where the last of the fighting may have taken place. A Welsh chronicler of the early sixteenth century, who gives valuable detail on Tudor’s march, says that the two armies met amongst the villages known as ‘The Tuns’, surely the communities of Atherstone, Atterton and Fenny Drayton referred to in Henry’s grant.16 The land around Fenny Drayton was particularly marshy and this area of wetland may provide an alternative location for the place name Sandeford (a causeway or crossing), where Richard was believed to have been slain. If Fenny Drayton marked the eastern extremity of the fighting, the victorious army would afterwards take the Roman road in the direction of Leicester, a line of march that would bring them to a place suitable for Christian burial of the slain, the church at Dadlington and its surrounding fields. Here Tudor’s men would have briefly halted, in remembrance of the battle and in thanks to God.

This is a substantial body of evidence, but one telling factor seems to work against it, the distance between the proposed battle site at Atherstone and the known place of burial at Dadlington. Burial mounds were normally found in the immediate vicinity of a battlefield. They were hurriedly dug in the aftermath of combat or the subsequent rout. A mass grave excavated at Towton in 1996 was discovered about a mile from the battle site. Many of the bodies bore multiple injuries, the skulls had suffered repeated blows and there were defence wounds to the upper arms, a desperate attempt to fend off the rain of deadly blows. This is the ghastly evidence of a killing ground. These men had been overtaken fleeing from the field and quite literally battered to death.

The ordinary soldier of the defeated army would thus be dumped unceremoniously in a pit, dug hastily and close to where he had fallen. If we accept the new site at Atherstone, where might this macabre disposal have taken place? A map of 1763 shows a location called Bloody Bank, set in open fields a little to the north of the town’s then boundary. In present day Atherstone, Bank Road derives its name from this previous landmark. The earliest oral tradition had it that this was indeed a place of mass burial following the battle in which Richard met his end. After Hutton’s book on Bosworth finally fixed in people’s minds a battle site eight miles to the east, this significant tradition was discounted. In the same way Royal Meadow, shown in early eighteenth-century plans of the field system lying north of Atherstone towards the River Anker, lost its association with Richard as Hutton made such a scenario seem impossible. But now, as we place the battle back in its earliest recorded location, the original derivation of Bloody Bank is re-established. This indeed would have been a place strewn with the carnage of the clashing armies.17

More formal commemoration also tended to occur close to the site of the fighting. The memorial chapel to the battle of Shrewsbury (1403) is situated close to the burial pits and also marks a decisive moment in the battle. It stands at the base of the hill down which the army of the rebels charged and where their captain, Sir Henry Percy, must have been killed. Richard III’s unfinished memorial at Towton was also placed close to the burial mounds of the slain. If we envisage the site of the battle of Bosworth as east of Atherstone, the furthest point of fighting recorded in Henry VII’s grant of compensation is in the parish of Fenny Drayton, over four miles from the church at Dadlington. Given this distance, most historians have assumed the battle must have been in the vicinity of Ambion Hill, either on the hill itself or about a mile further to the south, closer to Dadlington.

Yet Dadlington was not a chapel built to honour the slain, but an existing parish church, which then received bodies for burial within its bounds. The chantry chapel founded in the church, and dedicated to the souls of those killed in the battle, was a solemn record of the fact. It may have lain close to the battlefield. But we could be seeing something else, a careful act undertaken by the victors, the deliberate moving of their dead to consecrated ground. As has already been shown, an army would often prepare and move its most notable casualties in the aftermath of combat. This was usually a prerogative of the winners, though at the catastrophic English defeat at Baugé in 1421 the rearguard only arrived in time to search for the bodies of those of higher rank, which were then taken back to England for proper burial. But transporting the dead cost time and effort and normally only occurred with a few chosen individuals of rank and status. Here the slain of Tudor’s army might have been carried from the field en masse.

If so, Henry Tudor was making a remarkable gesture towards all those who had died for his cause. A popular belief amongst medieval fighting men was that the ground they fought on underwent a change of character, in which the blood shed in combat mirrored that shed by Christ on the cross. An improvised soldierly communion in the moments before battle used whatever was to hand, a three-leafed clover might be employed to represent the Trinity and makeshift wooden crosses erected amongst the troops. These rites echoed the liturgy recommended for the consecration of Christian cemeteries. But they obviously lacked official recognition or status. Most soldiers able to draw up wills hoped that if killed, their bodies would be recovered and either brought home or to a nearby ecclesiastical site, where they could be properly remembered. A victorious commander who recognised a particular debt of gratitude to his men would try to ensure that this happened.

There is compelling evidence that this is exactly what Tudor was prepared to acknowledge. Following his victory, he rewarded all those who fought under his banner. The generosity of his patronage was considerable. Even those of relatively humble status received grants for the term of the recipient’s life. A medieval monarch would be reluctant to make a large number of life grants, as these limited his capacity for future gifts, and Henry VII was notoriously cautious in this respect. But here a higher principle seems to have been operating, a deeply felt obligation to those who had fought for him. The course of the battle might explain such motivation, for some of the men grouped around Tudor’s standard had died saving his life. Their sacrifice left the victor with an abiding sense of gratitude to his followers. There was no surer way of showing this than to enable the slain to be buried in land properly consecrated. If Henry Tudor and his army left the field of battle along the Roman road from Fenny Drayton, heading towards Leicester, Dadlington would be the first parish church on the route. This gives a persuasive explanation for the Dadlington chantry memorial. Not only was the battle named from its principal burial site, but the site itself had a symbolic significance to the victor, the first consecrated ground passed in the aftermath of combat.

For this reconstruction to be feasible, the last of the fighting must spill into the vicinity of Fenny Drayton and Atterton. This is suggested by Henry VII’s grant of compensation and additional evidence supports it. There is a most intriguing place name, Derby Spinney, three-quarters of a mile north of Fenny Drayton, close to the Atterton Road. Earliest accounts have Sir William Stanley presenting Tudor with Richard’s battle crown as the struggle ends. After Sir William’s treason and execution in 1495 his role in the battle was excised, and subsequent versions replaced him in the impromptu crowning with his brother, Thomas Lord Stanley, who was created Earl of Derby by the new Tudor King. Derby Spinney could mark the spot where this battlefield ceremony actually happened. One physical feature is of interest. A spring feeds a small stream, which runs under the road from Fenny Drayton to Atterton. This may be the location of Sandeford, the causeway or crossing where, according to Tudor’s victory proclamation, King Richard was slain. The retrieval of the battle crown and its presentation to the victor would have taken place close by. A few hundred yards away, by the Roman road Henry’s army would need to join to reach Dadlington, is a burial mound. Within Fenny Drayton local tradition has always believed that here dead from the battle were laid to rest. It might form a burial place for those of Richard’s followers killed in the last dramatic charge against Tudor’s position.18

In accepting this scenario, we remove the battlefield from the vicinity of Ambion Hill and put it on an open plain where cavalry could be used to far greater advantage. If Richard wanted his mounted troops to deliver the knockout blow it made little sense to put his army on a hill, an essentially defensive form of deployment. An aggressive approach to the fight required room to manoeuvre, so that units would not get in the way of each other. A cavalry charge could then be launched with maximum effect. We have every reason to believe that this is what Richard intended to do. The ambiguous placement of the Stanley forces in Atherstone, mid-way between the two armies, created uncertainty and tension, but the fact that they had not joined Tudor showed they did not rate his chances highly. If Richard moved decisively, they were likely to remain uninvolved. Tudor’s men had made the best of a bad situation and begun their advance in an effort to entice the Stanley contingent to join in. But Richard now had the chance he wanted against the much smaller army of his challenger, to confront him on the field, break his power and if possible kill him.

As Richard’s army waited for his opponent to appear, the King enacted a carefully thought out ritual in front of his soldiers. We have looked at the personal meaning of this for Richard himself. We now need to consider further its effect on his army. The ritual preparation of an army may seem a strange concept to us. Perhaps an echo remains in superstitions resorted to before important events, whether those be lucky objects or little repetitive actions made in order to feel prepared and so that the outcome will be all right. We are less accustomed to the preparation of a group that is initiated into a shared belief and joined in a common understanding. Yet such preparation was vital for a medieval army. The effectiveness of ritual could determine the way men fought and how battle might unfold. A force inspired by a shared cause that all could understand and believe in would have greater cohesion and unity. All depended on the power of the ritual itself.

A public enactment could communicate swiftly and effectively with those who watched it, when time was precious and the enemy approaching. A battle-speech would only be heard by a few and its content would have to be relayed to others. Visual display, however, through procession and ceremony, could be seen and understood immediately and gave onlookers a real sense of participation.

We have heard how a procession was made before the assembling troops at the battle of Verneuil. In the clash of arms which followed, the English archers were broken up by a shattering cavalry charge. But the survivors instinctively gathered themselves together and rejoined the fray with a great shout, thus inspiring their fellows and decisively turning the course of the fighting. A bond had been forged, a deep sense of connection, which could drive an army forward and hold it together.

A spectacle to create such an effect must have been visually stunning and full of symbolism. A surviving artefact found near the battle site, a copper-gilt processional cross decorated with the Yorkist emblem of the sunburst, suggests how such a ceremony might have been enacted.19 A processional cross would have been borne by a religious attendant at the head of a progress of the King and leading knights and supporters. Those watching would receive powerful evidence of the King as a consecrated figure, of his regal dignity and of his religious and secular authority. The defining moment of such a ritual would be the placing of the crown of England on the head of the anointed King. As we have seen, there is strong evidence that at Bosworth this was the priceless and rarely-seen coronation crown itself – the rich crown of Edward the Confessor.

This most precious object was believed to have been found in St Edward’s tomb. It was fashioned in gold, with cruciform arches worked with gems and precious stones. It was traditionally used only for the most sacred act of coronation and kept securely with the other regalia at Westminster Abbey. Its appearance on the battlefield was unprecedented and must have caused a sensation. No soldier could fail to be aware of the significance of such an event. Richard had earlier left instructions at Westminster Abbey that the anointing oil of St Thomas à Becket, a treasured relic used at the coronation, should be sent to him when requested, indicating that he had it in mind to re-enact the defining moment of royal consecration. What his troops witnessed that morning on the battlefield was nothing less than a second coronation.

The reference to the most precious crown occurs in a number of sources. The Crowland chronicle makes a specific allusion to it. It is also described in the letter sent to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, probably based on the eye-witness testimony of Juan de Salaçar. And John Rous tells us that along with the crown Richard had other items of royal treasure. These all indicate, as we have remarked earlier, that the ceremony made a considerable impression on those who witnessed it. We have also rehearsed the grounds of legitimacy upon which Richard’s crowning rested. It was part of a deliberate, choreographed sequence that included the wearing of a smaller crown, a gold circlet affixed to the helmet, on the march to the battlefield, and Richard’s subsequent donning of it as he prepared to enter the fray. But there was another dimension to this ritual that now needs to be thought about. Monarchs performed a second coronation when the lustre of their kingship had been tarnished in some way, using such a ceremony to represent a cleansing of whatever had marred their reputation and a chance to begin anew. Medieval English kings such as Stephen and Richard the Lionheart undertook it after a period of captivity, fearing that this had diminished their majesty. Edward IV had performed it after his exile abroad. Richard III may have had a different motive. Since his first coronation the princes in the Tower had disappeared and had almost certainly been killed on his orders. This was the common belief among his subjects. While his own supporters might understand the awful necessity of this act, and identify with the broader cause, the murder of children was a terrible sin that would inevitably stain the reputation of a ruler. Through his wearing of the coronation crown Richard was recognising and acknowledging this before his army. The forthcoming battle would represent a new beginning to his rule.

His followers may have wanted rather more than this. As soldiers lined up for a climactic battle, whose outcome could hinge on the intangible factors of combat, they would inevitably wonder if their commander might be punished by God for a particular sin or fault. This is the germ of Shakespeare’s portrayal, where the ghosts of Richard’s victims, and particularly the princes, undermine the conviction of his army. The Crowland chronicler intimated that the fate of the princes was in men’s minds as they drew up for battle. What Richard’s supporters needed was something even stronger than belief in a right cause, a demonstration of contrition before God. And this is exactly what they now got.

The most powerful act a knight could perform was to take the cross: to give a solemn pledge to God, before witnesses, to go on crusade against the infidel. In the late Middle Ages such a ceremony commonly took the form of a vow, supervised by priests and vouched for by fellow knights. In 1458 three Englishmen proposed ‘to fight the Turks in accordance with vows taken’. The three were young men with reputations to make.20 In Richard’s case, a reputation was to be retrieved. A crusader was offered remission of all sins confessed with a contrite heart. A ballad on the battle, preserved within the circle of the Stanley family, describes Richard’s crown-wearing but also notes him making an oath on the name of Jesus before the assembled army, in which he swore to fight the Turks. Richard was now pledged to a great enterprise, one that his family had longed for and Edward IV had disappointed in, to join a crusade to the East. The message of the battle of Toro was being repeated; victory against a rival claimant would end dissension and allow a military campaign against the forces of Islam. To a Christian soldier no war could bring greater prestige. Richard had levelled with his men. This gesture was the culmination of an extraordinary, planned ritual before battle, and no action could have done more to assuage doubters and inspire the rank-and-file. Their leader was repentant of the past and looking to the noblest of all causes for the future. This was a king for whom his men would be prepared to fight loyally and die bravely.

The royal army that Richard had taken such trouble to motivate had an intrinsic unity to which the King deliberately appealed. The vanguard was commanded by his trusted lieutenant, the Duke of Norfolk, who had acted promptly on the King’s behalf to snuff out armed rebellion in Kent in the autumn of 1483.The rear was led by the Earl of Northumberland, who had brought an army to support Richard when he seized the throne. All had fought together on the campaigns against Scotland at the end of Edward IV’s reign. In the King’s own division was a specially selected band of mounted knights, his closest followers and loyal family supporters. These included men whose allegiance to the house of York had remained steadfast over generations. Sir Robert Percy’s father had fought with York at Wakefield and narrowly escaped execution. Percy himself joined Richard’s service in 1469, when his master was first recruiting men to fight under his banner, and there he stayed, becoming controller of the royal household and, as tradition has it, captain of Richard’s personal bodyguard. He died under the King’s banner at Bosworth and his son continued to resist Henry VII years after the battle.21 Richard might well describe such servants as ‘his people’, remembering the forceful comment he made to his German visitor, von Poppelau, about how he wished to fight against the Ottoman Turks.

This strong sense of identification with fellow soldiers was echoed in the one book we know Richard commissioned as King – an English translation of the classical text on warfare by Vegetius.22 The appeal of this military handbook lay in the timeless commonsense of many of its dictums or sayings. In one of the most famous, Vegetius told how it was better to rely on one’s own knights and warriors in times of crisis than to bring in hired foreign troops. In accordance with this, Richard’s men were carefully chosen to defend the realm of England, and they were an entirely English army.

This could scarcely be said of the forces led by Richard’s challenger. As Tudor’s soldiers fanned out across the fields towards their opponents they were bound by a very different esprit de corps. This was a polyglot band, an assorted mix of nationalities: English exiles, French, Bretons, Scots and Welsh, along with those who had joined it for their own reasons as it entered England. The core of this army’s identity was not its idealism, its motivation for the cause of England, but was found in its paid professionalism. The majority were mercenaries, hired for the duration. They were skilled and competent but had no particular attachment to Tudor or to his claim. They regarded the whole enterprise as an incredible, albeit highly risky, adventure. The army’s backbone was a force of over a thousand French pikemen recruited from a disbanded war camp at Pont-de-l’Arche in upper Normandy. These men were highly trained and drilled by Swiss experts in the latest techniques of military manoeuvre. Henry benefited from this considerably more by luck than judgement.

Tudor’s French contingent was not interested in fine speeches or visually stunning ritual. They had been paid to do a job, and would be paid more when it was done, and it was a matter of professional pride that they did it properly. They were well aware of the risk involved, and presumably remunerated in accordance with this. Theirs was a dangerous occupation. But as they prepared for battle there was also a sense of elation. These men were adventurers and no more astonishing escapade could be imagined than trying to put Tudor on the throne of England in such unfavourable circumstances. Tellingly, one of the French later referred to this campaign as ‘the English adventure’, suggesting that this wry epithet was in general use amongst his fellows.23 The commander of the mercenaries, Philibert de Chandée, was a skilled and enterprising soldier of fortune. Chandée was eager for any daring undertaking. On the successful conclusion of the campaign he had no wish to rest on his laurels but quickly signed up for a new endeavour, this time to fight for Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain against the Moors of Granada. This was the way to make a martial reputation.

Two more different armies could hardly be imagined. Tudor’s rag-tag ‘international brigade’ was scorned by Richard in letters to his followers. There was an obvious propaganda value in this, but one senses the King was genuinely angry that his challenger was invading with so many foreigners and a large mercenary contingent. Yet the French were highly experienced, and were already putting their stamp on proceedings. As the armies converged it was their tactical acumen that shaped the emerging contours of the engagement. Hearing the direction Richard’s artillery was firing, they advocated the flanking manoeuvre already described. This would allow their vanguard to strike the wing of Richard’s army advantageously, with sun and wind behind them, rather than face the frontal assault of his missiles and fire. Tudor had concentrated most of his troops in the vanguard, under the command of the Earl of Oxford. There were more French troops than any other, so Oxford and Chandée organised their force along French lines, in companies of 100 men, each with their own standard as rallying-point.24 The massed pikemen would provide greater weight in the push and shove of the mêlée than the more lightly armoured archers of their opponents. So French skill-inarms gave Tudor his first advantage as battle commenced. It was to provide invaluable help as the struggle reached its climax.

Here our modern desire for a running order of events and a diagram of the action furnished with arrows, illustrating the position and movement of the participants, is going to be frustrated. The battle began when Tudor’s vanguard advanced and engaged with Richard’s, at some point during the morning of 22 August 1485. After that much is unclear. No-one involved in the chaos of medieval battle could have any idea of what was happening beyond his own immediate surroundings. By piecing together a number of accounts, each from its own perspective, we can recapture some of the key moments and gather a sense of what took place. The order in which they took place, and the cause and effect between them, is ultimately unknowable.

Up to now Richard’s actions that fateful morning have been interpreted in an entirely reactive way. In one such version the King sees a pause in the fighting and fears his soldiers lack the will to carry on the battle. In another, he becomes suspicious of the uncommitted troops of Northumberland behind him and again imagines that betrayal is imminent. A third has him wishing to forestall intervention by the forces of Sir William Stanley, mid-way between the two armies. Finally there is the suggestion that Richard’s rash and precipitate decision was his undoing, as he led an impetuous and foolhardy cavalry charge directly against his rival. Nowhere has this military initiative ever been seen as a positive and daring attempt to deliver a coup de grâce.

It is clear that at some point Richard caught sight of Henry, who was towards the rear of his own army, accompanied only by a relatively small body of troops. It is interesting to speculate how this separation from most of his men had come about. Henry may have simply failed to keep up with the rapid advance of his vanguard. Even less impressively, he may have been keeping an eye on an escape route should the engagement go against him. But in either case his vulnerability was apparent and it must have come to Richard that this was the moment for a decisive strike which could resolve the issue between them once and for all.

Richard now launched his cavalry charge. There are pointers that this was not a desperate gamble or a wild over-reaction. Instead of being spurred on by fear of betrayal or uncontrollable rage at the sight of Tudor, the charge can now be understood as the final act of Richard’s ritual affirmation of himself as rightful King. A sign was given to his men. Richard put on over his armour a loose-fitting robe, showing the royal coat of arms. Chivalric treatises made clear the significance of this. Once a knight displayed his coat of arms ‘in the hour and place of battle’ there was no turning back: ‘in that noble and perilous day, he cannot be disarmed without great reproach to his honour save in three cases: for victory, for being taken prisoner, or for death’. Richard was then seen to don his battle crown and take up his axe.25 These actions were considered and would send a decisive message to his waiting soldiers. Mounted and readied for combat, they would look to their leader for the signal to advance. The coronation ritual they had earlier witnessed had made clear to them what was at stake and the determination of the King to establish his divinely ordained rule and obliterate the opponent who had dared to challenge it. There was a growing momentum from which it would be hard to draw back. The charge expressed Richard’s deep desire for personal confrontation with Tudor. It was the culmination of his entire campaign. The issue was now to be decided by a duel to the death and the impetus towards this had become unstoppable.

Mortal combat between two kings was an idea elaborated in medieval romance and chivalry. In one illuminated manuscript popular at the Yorkist court two crowned leaders are depicted in a fight to the death as their assembled armies look on.26 Not only Richard, but also those following him would have understood these sentiments and been ready to play their part in enacting them. By the donning of his battle crown Richard gave the signal that such a clash was now imminent. The dramatic inevitability of the two men’s meeting head-to-head was so strong that the tradition survived for over a century and became the powerful conclusion to Shakespeare’s version of the battle.

Richard’s mounted force began to move forward, swinging wide to avoid the clashing vanguards before gathering speed to close on Tudor’s position. To gauge its effect, we can now draw on an exciting new source for this crucial phase of the fighting. It is an eye-witness account by one of the French mercenaries in Henry’s army, written the day after the battle, on 23 August 1485. It has never before been used in a narrative of Bosworth.27 This French soldier described Richard charging with his entire division, which must have numbered at least several hundred horsemen. It had previously been thought that Richard, unsure of his troops’ loyalty or in too much of a hurry, had only gathered a small group of household men. Use of his whole battle line suggests a prepared and deliberate plan of action. It must have been both a stirring and quite terrifying sight as it gathered speed.

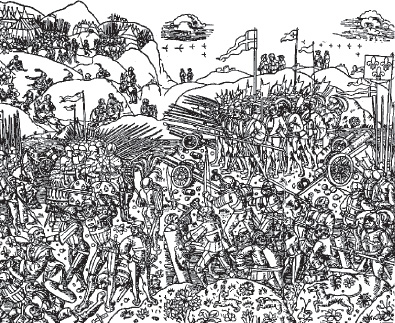

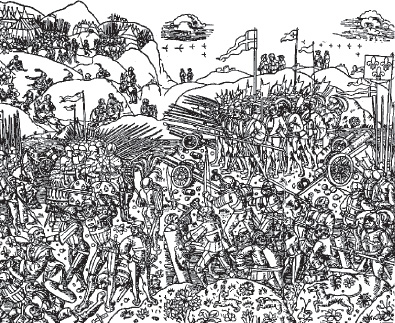

The impregnable pike wall: woodcut of the battle of Fornovo 1494, showing the formation used to such deadly effect at Bosworth.

Then something completely unexpected happened. The French account hints at the pandemonium among Henry’s own retinue as Richard’s force was sighted. Henry dismounted, to present a less easy target for his opponent, and following a desperate appeal for help, pikemen were hurriedly pulled back from the vanguard to protect him. What is then described is a complex military manoeuvre, only recently devised by the Swiss to counter Burgundian cavalry, and first deployed in the battle of Grandson in 1476. We know that the French recruited by Tudor had been drilled in Swiss fashion. Their training enabled them to drop back at a run and close around Henry in a square formation through which cavalry was scarcely able to penetrate. A bristling mass of weaponry would now be presented to the opposing horsemen. The pike was an eighteen-foot long wooden stave with a steel head. It was formidable in tight, unbroken formation. The manoeuvre perfected by the Swiss allowed a reformed front rank to kneel with their pikes sloping up, the second standing behind them with their weapons angled, the third with the pikes held at waist level. No mounted attack could break through such a line. To enact this at speed and over distance required years of training and an instinctive drill technique. It was a tactic Richard could never have seen before, and he had no way of anticipating it when he ordered his charge.

There must have been a terrible collision between Richard’s mounted troops and the wall of pikes, the clattering shock of impact followed by sheer chaos as riders crashed into the formation, and those behind into their fellows. Some may have attempted to ride into Tudor’s massed infantry, others, unhorsed, to attack on foot. But the force of the charge was broken, leaving its participants isolated and vulnerable. The French account recollects Richard crying out in rage and frustration, cursing the ranks of pikemen. This seems a genuine memory from someone close enough to hear. Although it is impossible to know the exact sequence, it seems likely that at this point Sir William Stanley decided to commit his forces against the King, and his men began to move towards the fighting around Tudor’s banner. The battle was nearing its awful climax.

Richard now faced a crisis. Most sources agree that the King’s supporters urged him to flee at some stage of the fighting, and this has generally been placed earlier on, before the cavalry charge. But now, with the charge broken and Stanley advancing, seems the likeliest moment. Richard was offered a horse and told to quit the battlefield and save his life. This suggests that he and his followers had already dismounted and were attempting to break through the pike wall on foot. There is an echo here of an earlier battle, at Bannockburn in 1314, when English cavalry were breaking in defeat against Scottish spearmen. The King of England that day, Edward II, was given a fresh mount and sent at speed from the battlefield. Thus he remained alive and did not fall into the hands of the enemy. But Richard spurned the opportunity. His reply was grimly defiant. He would finish the matter, and kill Tudor, or die in the attempt. It is so different from Shakespeare. Instead of crying out for a horse, he resolutely refused to use one.

This was an heroic way to fight. All contemporaries, even the most critical, spoke with admiration of Richard’s courage, seeing his actions as those of a bold and valiant knight. There was a sense of awe at the ferocity of his last attack, as he and his men now hurled themselves into the thickest press of their opponents. There was still an opportunity to win the battle if his diminishing band could break through and overcome Tudor, for during the Wars of the Roses, once an acknowledged leader was killed his army usually stopped fighting. Stanley’s men were approaching and Richard’s division was cut off from help and reinforcement. There was so little time. The King’s men seemed to have joined in a body around his standard, and endeavoured to cut their way through to where Henry stood. They came desperately close to success. They smashed through the pike wall and engaged the small retinue guarding Tudor in savage hand-to-hand fighting. The rival standards were only yards apart as this last surge carried Richard towards his challenger.

In the maelstrom of combat the King still had a chance to secure victory. He reached Tudor’s standard and cut it down, killing the standard bearer William Brandon. The toppling standard was bravely retrieved by one of Henry’s Welsh bodyguard. Men were struggling viciously all around. It seemed as if Richard might still carry the day.

Another of Tudor’s soldiers, Roger Acton, later remembered the last defence of the standard and how he was there ‘sore hurte’. A desperate stand was made, with the fate of the battle hanging in the balance, for Henry’s supporters feared he would now perish under the assault. A strong knight, Sir John Cheney, threw himself in Richard’s way to protect his master. Richard flung him down. Tudor could only have been feet away. But now Stanley’s men had arrived and Richard’s own followers were being overwhelmed. The royal standard-bearer had his legs cut from under him and in a bloody denouement Richard was overpowered with blows and battered to death.28 Nearly twenty-five years before, his father had perished in combat at Wakefield and his corpse had been mocked with the adornment of a false crown. Now Richard’s gold crown circlet was hacked from his helmet. It was a terrible end to the story.