CHAPTER EIGHT

Stress and Resilience

Everything that occurs in life—from the inception of a cell to daily events, big and small, to the dying breath of every living thing—is the result of a certain kind of friction, of interaction, and we can call this kind of stimulation stress. When we define the word this way, as a form of interactive energy, it’s possible to look at it with some neutrality, as just a fact of life (if not the central fact), without the negative connotations we tend to heap on it. It’s important to do this because, in the short term, the stress response is very much a motivator of life, of action, and certainly of interaction. However, when stress becomes chronic, when our life challenges surpass our ability to effectively cope with them, it becomes problematic for our psychological, emotional, and physical health. At that point, stress can grow into an unrelenting burden on our body, mind, and spirit and it has the capacity to undermine our health, exacerbate disease, and shorten our life span.

Stress is woven into the very fabric of life and we have a physiological response that is hardwired into us—the fight-or-flight response—that keeps us out of imminent danger. But when stressful events become overwhelming and switch from being an acute daily occurrence into a chronic issue, the change can trigger not just negative psychological and emotional reactions but it can also cause physiological damage. A growing body of scientific data and research show how stress impacts all aspects of our lifestyle and all aspects of our physical health.

In terms of stress and cancer, we now know that stress modulates key biological processes linked with cancer risk and progression, and that chronic stress is associated with worse outcomes for those with cancer.1 In fact, chronic stress dysregulates the immune system, decreasing our body’s natural defense against cancer, and leads to increased inflammation.2 At the same time, stress promotes tumor growth by releasing into the bloodstream proteins and hormones that help tumors enlist the body’s resources for cancer’s singular purpose—to grow.3,4 Most frightening is that we now know stress has the capacity to modulate key cellular processes, literally down into the nucleus of every cell in our body, and modify genetic pathways that make our bodies more hospitable to cancer growth.5

While increasing research points to the health dangers of stress, the good news is that stress is not genetic. None of us are condemned to live a stressful life. In fact, stress is something we can actively control and manage. Researchers at UCLA found that caregivers, who often face intense levels of chronic stress, were able to change their inflammatory profiles by engaging for twelve minutes a day in a specially designed yoga meditation.6 What’s more, the directed meditation had a dramatically greater effect on their biomarkers compared to having caregivers rest and listen to calming music.6

In my own research with breast cancer survivors undergoing radiation therapy, I have found that yoga does more than simply fight fatigue and improve aspects of quality of life (which are important for cancer survivors undergoing chemotherapy and radiation).7 Patients who incorporated yogic breathing, relaxation techniques, and meditation with their yoga practice improved their general health while reducing their stress hormone levels. So, while chronic stress poses serious health risks, the solution is readily accessible, free of charge, and the only side effect is that it also makes you feel great.

The Unique Emotional Stress of Cancer

There is nothing that can bring on acute mental, emotional, and physical stress like a cancer diagnosis. One minute you are living your life and the very next, all of it is up for grabs. For many people, especially if the diagnosis is of advanced cancer, you are thrust into acute awareness of your own mortality. Very few things in life are more stressful than this.

The shock of a cancer diagnosis can even be quite traumatic.8 Like a tsunami that makes landfall without warning, it can flood a patient with high-grade anxiety that literally washes over every aspect of life: Will I live? Will my children be okay? Will this bankrupt my family? Will my spouse or significant other carry on without me? Will I still be able to work? Will I be disfigured? Who will take care of my pets? A wave of shock rushes in upon us, and we may be catapulted into a full-blown state of traumatic stress. At the very least, we’ll be awash in feelings that we may have spent a lifetime avoiding or we may experience new, tough feelings for the first time.

Psycho-oncologists are beginning to study the emotional trauma that cancer can bring with it. Initially, the emotional trauma cancer patients experience can be acute (what the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, classifies as “Acute Stress Disorder,” or ASD).9 If this is dealt with right away, the patient is then able to work through the other feelings that ride in behind the initial trauma. The traumatic response, however, can often be delayed and then shows up as longer-term PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder.10 PTSD has been studied in patients with melanoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and breast cancer, among others. Taken collectively, these studies (which use the full DSM-IV diagnostic criteria) show a range of 3 to 4 percent of early-stage patients suffer some form of psychological trauma, while up to 10 to 15 percent of cancer survivors can suffer from some type of clinically defined mood disorder such as depression or anxiety during or after treatment.11 When a less clinically conservative measure of mental health is used, such as depression screening measures that have been linked with biological outcomes and survival, the numbers balloon, with more than 35 percent of early-stage patients exhibiting signs of trauma and up to 80 percent of those with recurrent cancer showing signs of this kind of psychological stress.11–15

Successfully addressing the trauma of cancer is a crucial first step in a patient’s journey: only when the overwhelming psycho-emotional stress of the disease is acknowledged and treated can the patient begin to work on building the emotional resilience that is needed to build an anticancer life.

The Emotions of Mortality

We live in a culture that encourages the suppression of emotions, where stoic silence is prized over honest, open emotional expression and sharing. Perhaps nowhere is this truer than in the context of cancer care, where a patient is encouraged to “fight” and “battle” the disease and to “live strong” in order to survive. This expectation for battle readiness, for a certain kind of emotional hardness, is not the most beneficial approach to dealing with cancer, nor is it even possible for the newly diagnosed.16,17 Certainly every cancer patient must have the courage to face the unknown, but before there can be courage, there must be acceptance, and before there can be acceptance, there has to be an honest willingness to express and process the complex feelings that cancer brings with it.

It is important that the primary medical team a cancer patient works with understands the emotional and psychological implications of the diagnosis. This is where integrative oncology becomes so crucial.

Every cancer patient must be encouraged and allowed to express his or her fears, hopes, and desires, ideally even before any treatment decisions need to be made. But this isn’t always easy: How does a young mother express her fear of dying without terrifying her young children? How does a single man approach his parents for financial support while he has to cut back on work during chemotherapy? How does a woman express her fear that her husband will no longer find her attractive after a double mastectomy?

These questions are valid, honest, and important, and it’s our job as cancer care professionals to become aware of the need for patients to find or develop the tools they will need to work through the complex emotions that cancer brings. Otherwise, straightforward feelings like sadness may morph into chronic depression or unaddressed fear might turn into chronic, debilitating anxiety. Dealing with the authentic, necessary, and very human emotions that come to the surface not only prevents the onset of serious mental illness, like those I just mentioned, but also fortifies the patient to focus on healing.

First we have to help cancer patients identify the emotions they are experiencing. This can be done by an empathic oncologist or an experienced nurse and certainly by loving and supportive family members and friends. But sometimes just lending an ear is not enough, and throughout this chapter, I will discuss the ways that cancer patients—and the rest of us—may cultivate peace of mind, which is the essential ingredient to successfully making any significant and lasting lifestyle changes. When we identify, express, and work through our emotions, we are then able to tap into our “gut,” or what I think of as our body’s innate intelligence, and make decisions with this intelligence in mind. This is especially crucial when one is dealing with a serious disease such as cancer. When we’ve acknowledged and dealt with our feelings, we better position ourselves to make decisions that reflect our true values and desires, rather than making decisions based on the fear or anxiety that stress brings. Being in emotional balance allows us to make healthy lifestyle choices that will enhance our ability to heal.

Here is a list of some of the common emotions related to a cancer diagnosis or other life circumstance that puts us in touch with our impending mortality. Which ones have you experienced, whether you’ve had cancer or not?

-

Anxiety

-

Fear

-

Anger/rage

-

Depression

-

Denial

-

Impotence

-

Regret

-

Guilt

-

Loneliness/alienation

-

Broken

-

Shame

-

Confusion

-

Overwhelmed

Was there someone you could share these feelings with? Were you able to acknowledge, honor, and process these feelings so that you felt more emotionally integrated and able to face the reality of your situation? In terms of your emotional life, do you feel understood and respected? If you have cancer, is your medical team aware of your feelings and working in a way that includes your emotional concerns? Are your loved ones also aware of the emotions you are grappling with?

The feelings that come up in life are tough and intense, but absolutely natural and necessary. Acknowledging them within yourself, and openly with others, will prepare you for the unavoidable stressors that come along with life’s challenges, including a cancer diagnosis, in ways that will provide lasting benefits.

Developing emotional magnanimity is essential to keeping at bay the stressors that are known to aggravate cancers and other diseases. In this chapter, Alison and I will discuss the groundbreaking research that’s been done on the link between stress and cancer proliferation and we will offer practical tips for how to reduce stress in your life in ways that will help keep cancer contained as well as improve your overall sense of well-being and health.

It is important to note that stressful events themselves, the stressors, which seem unavoidable in our current culture and climate, are not what cause the harm. It is our reaction to the challenges in our lives that does the real damage. To prevent disease and live as healthfully as possible, it’s imperative that we learn to manage our stress, which means managing our reactions to stressful events and exchanges in our daily lives. Only when we’ve got stress under some control can we make the kind of positive lifestyle changes that make up anticancer living.

Embracing Reality

Some cancer survivors describe being diagnosed with cancer as “the best thing that ever happened to me.” But not Molly M., the woman you met who has lived for the past eighteen and a half years with the most lethal form of brain cancer. “Getting cancer was awful. But it forced me to slow down and really listen to my body. I had to leave my students and the teaching job I loved, but, ironically, my new full-time job became educating myself so I could heal myself and help others. I would never describe cancer as the best thing that happened to me, but I will say this: It has made me wiser. The bottom line is, I had a choice: I could let cancer be in charge or I could be. I decided I was more important than the disease and now I’m focused for a significant portion of every day on anticancer living.” Molly describes the kind of fierce pragmatism that cancer can bring out in us. A cancer diagnosis or other life-changing events have the capacity to ground us firmly so we can step with purpose onto the anticancer living path. But first, we have to deal with our feelings and find some emotional equilibrium so that we fortify ourselves against the inevitable distractions life will try to throw at us. When we develop the skills we need to keep stress at bay, we can begin to make lifestyle choices that prioritize health and well-being over stress and disease.

Is a Positive Attitude Helpful?

One of the really surprising sources of stress I hear cancer patients discuss is the pressure they feel under by well-meaning family and friends—even strangers. Being told to simply “Stay positive!” or dismissed with “You’ve got this!” or worse, things like “I read this is an easy one to beat,” puts unnecessary pressure (stress) on the cancer patient and can also make them feel dismissed or diminished, though this is usually the last thing the person who said this intended. Being asked to adopt a peppy mind-set isn’t the same thing as being encouraged to find your way to an optimistic outlook. I realize this is a somewhat subtle distinction, but I’ve seen too many cancer patients, especially those who face a recurrence, blame themselves for somehow not having the right “positive” attitude. As a psychologist, I’ve come to realize that not everyone knows what to say when they find out someone has cancer, and some people, even close friends and family, don’t have the capacity to be as supportive or present as we might hope. The important thing for cancer patients is to focus on bringing people into their lives who are capable of being more emotionally supportive and empathetic.

Michael Lerner, PhD, has been exploring the subtle messages we convey when we think we’re being supportive and cautions that telling people with cancer, “You’ll beat this if you just stay positive,” puts the emphasis in the wrong place. It forces the patient to fixate on the cancer rather than on building a joyful and purposefully healthy lifestyle around the cancer.18 “People need to be allowed to experience whatever it is they’re experiencing,” he recently said to me, “whether it’s fear or anxiety or depression or an opening to the beauty of the world or love.” He went on, “When one practices being joyful, being happy, being in touch with the vast mysterious beauty of the world, this is quite constructive and can be powerfully transformative. I’ve known people who have fallen madly in love for the first time even as they are dying of cancer. I can’t think of a more positive life experience than that.”

Lerner, like many at the forefront of the anticancer living movement, emphasizes that forced optimism can be toxic and that the goal is to become relaxed and skillful with handling our emotions. When we do this, he believes, it will naturally lead to a more positive outlook on life, greater intimacy with our fellow mortals, and a keener ability to live in the here and now.

Getting out from under the vast cloud of stress that seems to blanket our world (or what Elissa Epel, a leading health psychologist and the coauthor of The Telomere Effect, refers to as leaving “the house of stress that we all live in”) is a key step onto the path of healthy living.19 It involves a turning inward (toward the calm, knowing center that we all have inside) and consciously accepting all the feelings that our morality awakens in us. As David Servan-Schreiber put it in his memoir, Not the Last Goodbye: Reflections on Life, Death, Healing, and Cancer, “One of the best defenses against cancer is finding a place of inner calm.”20

Glenn Sabin, the longtime cancer survivor whom we introduced in part 1, also credits his ability to find inner peace with his capacity to move beyond the initial emotions of his diagnosis. “Being in a calmer frame of mind provided me the mental means to dig deeper for answers to how I might manage my disease in a meaningful way. How I could create health in spite of disease. The foundation to my health was achieving an unfettered mind.”

What is quite remarkable, and I believe has the power to imbue a cancer diagnosis with a profoundly human kind of “opportunity,” is that each of these remarkable people made the decision to remain hopeful in the face of life’s great uncertainty. This hopefulness allows a person (whether cancer is present or not) to step out of fear and into action. Moving past fear allows us to approach life with renewed awareness and curiosity and to focus on the deeper rewards life still has to offer us, regardless of our prognosis. When we surrender to the truth of our (health) circumstances and turn inward for answers, we are then able to tap into our innate, powerful sources of healing.

I recently asked Diana Lindsay what was the key to her miraculous recovery. “I would have to say that I don’t know,” she responded. “I entered the world of not knowing and I remain in the world of not knowing. But if I had to try to articulate it, I’d start by saying, ‘First of all, you have to pick yourself up off the ground when you get a prognosis like mine and you have to be willing to hope, to take the risk of hope.’ I made a complete commitment to healing, gave everything up, and just completely dedicated myself to it. I learned to listen to my body and discern what it needs, and now I do everything I can to help my body stay well.”

Monastic Mind Control

Western doctors have long been both intrigued and suspicious of claims that the mind can have such a dramatic impact on our bodies and our health. In the early 1970s, Dr. Herbert Benson, a Harvard physician, took a team of scientists to Northern India, where he had heard of a group of Tibetan monks who, through meditation, claimed they could control aspects of their physiology. The prevailing Western belief at the time was that physiological processes such as heart rate, blood pressure, and skin temperature were not under the control of our minds. What Dr. Benson found astounded him. The monks had exquisite control over their own physiology. Using only meditation, they were able to lower their heart rate, decrease their blood pressure, and decrease or increase their body temperature to specific parts of their body.21

Subsequently, Richard Davidson at the University of Wisconsin brought some of these same monks and others into the laboratory to study how their brains worked.22 He found that the monks who had been meditating for extensive periods of time had distinctly different brain function than the general population, and they responded to stressors in a very different way than nonmeditators or novice meditators, with reduced heart rates, lower metabolism, and slower breathing.21,23,24 They were more in control of their reactions, physiologically and psychologically, and able to maintain a state of calm even during stressful situations.

Almost forty years ago, Jon Kabat-Zinn, the creator of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, started a clinical and research program that developed a practice he called mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR).25 MBSR is typically an eight-week program incorporating a combination of different practices from Eastern traditions, with an emphasis on Vipassana meditation, a form of mindfulness meditation. Through decades of research, Kabat-Zinn and his team have discovered that, even after just eight weeks of MBSR, patients showed distinct changes in the electrical activity of the brain.26 Brain regions that process positive emotions increased in activity, and brain regions that process negative emotions decreased in activity. Their research also reveals a direct correlation between changes in the brain due to meditation and how well the immune system functions. In one 2003 study, Kabat-Zinn, Davidson, and their team studied the electrical activity in the brain of meditation-naive participants who went through the eight-week stress-reduction program compared to a control group that was waiting to take part in the program. At the end of the eight weeks, both groups received a flu vaccine. The people who had been through two months of MBSR experienced an enhanced immune response that allowed their bodies to respond better to the vaccination. What’s more, researchers found a dose-response effect in the relationship. In other words, the more someone meditated, the more effective the vaccine.26

There are many kinds of meditation, but some common features include focused and controlled regulation of breath, and, to some degree, control over one’s thoughts and feelings. This is not really “control” in the traditional sense. The intent is to allow thoughts and feelings to float by without allowing them to lead your focus away from your breathing.

Focused-Attention Meditation

A focused meditation usually starts with the breath and could be followed by reciting a syllable or phrase, or a simple prayer. You also could focus your attention on a burning candle or on an image that affects you.

Mindfulness Meditation

With mindfulness meditation, thoughts, feelings, and emotions may be coming and going, but the key is not to focus on them and to let them freely come and go. This takes practice and can be more challenging than focused meditation. If you get distracted or start fixating on a thought or object, don’t get upset with yourself. Just bring yourself back to your breath and try again.

Compassion-Based Meditation (Also Called Loving-Kindness Meditation)

Loving-kindness meditation is essentially about cultivating love. Start by cultivating the feelings of love and compassion you have for someone close to you. Then send that loving-kindness toward yourself and foster self-compassion. Then shift to family, friends, and close loved ones. In the third phase you may choose to focus on a challenging person in your life with whom you are having a conflict or struggle. And finally focus on strangers and send out loving-kindness and compassion to everyone.

Dr. Sara Lazar at Harvard University took Kabat-Zinn’s research a step further and measured, using MRI scans, whether there was a change in the actual anatomy of the brain after the eight-week MBSR program.27 She found a decrease in the size of the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for the fight-or-flight response, and an increase in the size of the hippocampus, the part of the brain related to memory. So, just like we exercise to improve our heart function and increase the size of our muscles, the same thing can be done with mind-body practices—we can exercise our brain to change the way it functions.

The Surprising Benefits of Meditation

Research published in the past ten years clearly demonstrates that meditation not only changes our lives but also modifies brain function and anatomy, reduces inflammation, modulates key biological processes right down into the nucleus of cells, changes gene expression, relieves anxiety, improves memory, and lowers stress hormones in the bloodstream.28–33 At Wake Forest, researchers found that if they trained people to meditate, they could reduce the experience of pain (in this case a 120-degree hot pad placed on their right calf for six minutes) by 40 percent.34 In comparison, morphine and other pain-relieving pills typically lower pain by 25 percent. Psychologists now train U.S. Marines to meditate as a way to keep them focused and alert in war zones. Researchers found that if marines meditated for at least twelve minutes a day, they increased their ability to maintain attention and retain working memory when facing life-or-death situations.35 African refugees suffering from post-traumatic stress who were taught meditation techniques were able to dramatically reduce their anxiety, replicating previous findings showing that meditation reduced depression, insomnia, and alcohol abuse in Vietnam veterans.36,37

I know from my own experience that, for the breast cancer survivors who go through the CompLife Study, learning a mind-body practice is often what they cite as the most life-changing benefit they take away from the intervention.38 As part of the study, patients learn a form of seated meditation and a yoga-based movement practice (“sun salutations” for those of you familiar with Vinyasa yoga). Patients are asked to increase their daily practice (over the course of six weeks) to twelve sun salutations a day, a brief relaxation technique, and up to twenty minutes of guided meditation. In our exit interviews, participants consistently point to the stress-management component as key to helping them change their outlook, improve the quality of their lives, and engage in healthful diet, exercise, sleep habits, and relationships.

These women do not come from privilege and they did not run away from their lives or quit their jobs as a way to find peace. They simply change their reaction to the stressors they face on a daily basis. Take Brucett M., for example. Brucett works as a merchandizer in Houston, setting up displays in stores. She’s on her feet most of the day and then comes home to a bustling household that includes her husband of sixteen years, two grown children, and two teenagers. She was only forty-three when she was diagnosed with stage II breast cancer. For Brucett, like so many of the people I’ve encountered, finding a way to manage her stress was key to her long-term survival and to enjoying her life. She tended to let things get to her—encounters she had during the day, exchanges with her kids that seemed rude, times when she wished she had said something but hadn’t. Meditation made her more aware of herself and more conscious of her reaction to stressors. Here is how she described the change to me, “I don’t know if anyone has ever felt like this. To have so many questions, but the answers are trapped in you. That’s how I’ve felt for so long. Well, I’ve come to realize that through meditation and deep relaxation that my answers are flowing. I can honestly say that I’ve never been in such deep thought about my life.”

Many mind-body practices originate from Eastern countries such as India, Tibet, and Japan and from religious practices (e.g., Hinduism or Buddhism) thousands of years old. The Western Christian tradition also includes such practices as contemplative prayer. Humans on every part of the planet have found ways to focus inward on oneself, on one’s connection to others, to a higher power, and to the world as a whole. Engaging in a mind-body practice is a time to seek calm, when we can slow down and bring awareness to the moment. Fostering and expanding one’s spirituality and life purpose is an important aspect for achieving optimal health and well-being. People can modify the practices to meet their own individual needs and to ensure that they remain aligned with their own religious practices. Indeed, we work through these issues often with our own patients. For example, one of the CompLife patients with a deep Christian practice had some initial concerns of whether the yoga and meditation would conflict with her practices and beliefs. In fact, the opposite occurred. By making subtle modification in the language used in the yoga and meditation, the patient expressed later that she had never felt closer to her God than in the mind-body sessions.

Brucett’s transformation and a growing body of research point clearly to the power of our minds to help us through stressful times, such as a cancer diagnosis, and maintain our focus and purpose through every challenge we face. My only question is this: when the benefits of meditation appear so extensive and varied, why aren’t all of us taking fifteen to twenty minutes a day to focus on our breath to rejuvenate our mind, body, and spirit?

The Stress and Cancer Proliferation Loop

Though there is no scientific data to indicate that stress causes the onset of cancer diseases, there is a growing body of research that does link chronic stress with cancer tumor growth and with cancer proliferation.

Anil Sood, MD, my colleague who works in the department of gynecological oncology at MD Anderson, has for nearly twenty years been conducting groundbreaking research on how chronic stress, which includes psychosocial factors like chronic depression, anxiety, and social isolation, has a direct influence on cancer’s ability to grow and spread.39–41

The major cause of all cancer deaths is metastasis, when cancer spreads from its original site in the body. When metastasis occurs, cancer cells can break free of their original tumor, travel through the blood system, lodge in different areas of the body, adapt, adopt a new blood supply, and flourish. When a cancer has progressed into this process, it becomes extremely difficult to treat. The steps of metastasis include angiogenesis, proliferation, invasion, embolization, and evasion of effective immune system surveillance. Research has shown that chronic negative affect in a patient is linked with the sustained (or chronic) activation of these proliferation processes.3,39

One of Sood’s most telling experiments involved a group of mice that were injected with a specific amount of ovarian cancer cells.42 He exposed some of this population to two hours of restraint stress daily for three weeks (mice get stressed when they cannot move) and let the others go about their business. The animals that were restrained had tremendous growth of their cancer and in the spread of the disease throughout their body.

Sood found that the main culprit in causing the tumors to grow and spread was the stress hormone norepinephrine. When he blocked the effects of norepinephrine (he used a common beta-blocker called propranolol, but in humans we can use meditation or other stress-management techniques), the effects of stress on tumor growth totally disappeared. The animals that had norepinephrine blocked and were exposed to stress had the same outcome as the animals not exposed to stress.42

These experiments on the effects of stress on cancer growth have now been replicated in other animal studies and clearly show that stress leads to biological changes that make the tumor microenvironment more hospitable to cancer growth.3,43–45 Sood and others have clearly demonstrated that chronic stress, and the cascade of stress hormones that ensue, can influence ALL the cancer hallmarks and other biological processes linked to cancer growth.1–4,31,42,46–49

Additionally—and stunningly—what Anil Sood and others have discovered is that as cancer proliferates and spreads, tumors secrete inflammatory products called cytokines that can actually affect the brain.50 As Sood recently explained, “Think about that: We know now that people experiencing excess stress have higher levels of inflammation, and, in parallel, an active, proliferating tumor releases these same inflammatory factors that can actually stimulate a stress response in our brains that will change the biobehavioral state of the patient, which may lead to increased depressive symptoms.” In other words, cancer not only causes psychological stress, but it may actually influence our mood through biological changes it causes in our bodies. As Sood explains, “There is a bi-directionality here that shatters the myth that there is a disconnect between our affect (what we think of as our emotional state), in regard to chronic stress, and how cancer behaves.” There is now also evidence from Sood’s laboratory and others that not only do tumors create their own vasculature to keep them well fed with blood and that stress enhances this process, but tumors also develop their own nerve supply. Again, this tumor-based neurogenesis is facilitated by chronic stress and the release of stress hormones.3,41 What this research shows us, unequivocally, is that chronic stress and cancer create a bi-directional loop that supports the proliferation of the cancer and may influence the state of mind of the patient.1–4,42,49

Another important area of research demonstrating that chronic stress can reach into the nucleus of every cell and create damage is work we touched on in chapter 4 on telomeres and telomerase. Telomeres are on the end of chromosomes, which are found in the nucleus of every cell in our body. Telomeres protect the structural integrity of the chromosomes. As telomeres shorten, we develop what is called chromosomal instability. When cells that have chromosomal instability multiply, it can lead to mutations. If left unchecked, chromosomal instability can lead to cancer. Within the nucleus of our cells we also have an enzyme called telomerase that helps keep the telomeres “healthy.” With each cell division there is a slight decrease in telomere length, something called telomere attrition. As we age, our telomerase decreases and our telomeres shorten. Telomere attrition is, in fact, part of the normal aging process and telomere length is thought to reflect a person’s biological age.

Researchers Elissa Epel and Elizabeth Blackburn tracked the mothers of healthy children and compared their telomere length to the telomeres of mothers who were caring for children who suffered from chronic illness. The mothers who were caring for sick children had shorter telomeres and lower levels of telomerase.49 In addition, the length of time they had been caring for their chronically ill children was reflected in their telomere length. The longer their caregiving, the shorter their telomeres. Chronic stress was literally speeding up their aging process.

Because we are living longer, more people are forced into roles of caregiving who do not have training as nurses or aides. Informal caregivers now account for 80 percent of the long-term care provided in the United States. Caregivers face an incredible burden and it is vital that they don’t take on this burden alone.51 The stress of caring for a loved one can become chronic and lead to reduced immune function, increased inflammation, and disease and earlier death in the caregiver.52–55 If you are providing care for someone, here are some steps you can take to manage and control your own stress so you don’t get sick, too:

-

Don’t go it alone. Social support is key to maintaining your sanity and your health. This might mean reaching out to friends and loved ones and/or joining a caregiver support group where people can relate to what you’re going through. The added benefit of a support group is that they can put you in touch with other resources that could help to relieve some of the pressures you are undoubtedly feeling as the primary person responsible for someone’s health and well-being.

-

Recognize your limits. You cannot be the perfect aide. If you try to provide everything, all the time, you will eventually break down yourself. Find ways to give yourself breaks from constant care, even if that means that someone else comes over for just a few minutes a day or a couple times a week. Take full advantage of that time away. Don’t use it to grocery shop or do other chores for the person you’re caring for. Take the time for yourself and engage in a mind-body practice.

-

Set goals for yourself. Break tasks into small steps and establish a daily routine. Don’t take on added burdens. Say no to people who ask for your help with something outside of your caregiving duties. Limit your commitments and focus on caring for yourself.

-

Accept help. The only way for you to reduce your own burden is to allow other people to help you, even if they don’t know the ways of the person you’re caring for or they don’t do things exactly the way you would. Learn to let go whenever you can. It will help to keep you strong and avoid disease.

-

See a doctor. Don’t help keep someone else alive at the expense of your own health and well-being. It’s better for both of you if you are putting yourself first.

-

Engage in healthy behaviors daily. One of the biggest problems faced by caregivers is that they tend to not take care of themselves, mentally or physically. Find a way to maintain your own health, even if that means playing an exercise DVD in your home or eating cut-up vegetables instead of cookies as a snack. Little things add up. Stay on the right side of your own health by making healthy choices every day and engage in healthy eating, exercise, stress management, and good sleep habits.

Stress and the Body

When looking at the dangers of stress on our health, it is important to understand the difference between chronic and acute stress. When we feel stressed—which means when we feel like we are in the presence of imminent or perceived danger—a cascade of chemical processes is triggered that courses throughout the entire body. We all know what happens when we are startled: We’re flooded with the stress hormones cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, our heart rate spikes, our breathing quickens, then we may begin to sweat. These are biological signals that we are ready to act! What primes us for action is the release of stress hormones, like cortisol, which, thanks to the efficient delivery system of our bloodstream, highjacks our regulatory systems until the danger has passed.

But what happens when we can’t turn off that fight-or-flee response and we’re awash in cortisol for an inordinate amount of time? This is when our body starts to suffer from the interruption in regular service it’s used to getting from those key regulatory systems that have been instructed to shift into “idle.” Here’s an analogy that may help. Think about what it’s like when you’re driving to work and you hear a siren approaching from behind. You glance into your rearview mirror and see that an ambulance, its lights ablaze, is barreling toward you. What do you do? You slow down and pull over to the side of the road. Once the emergency—the ambulance—has passed, you get back on the road and continue your journey.

This is what acute, short bursts of stress look like, and these are inevitable and quite harmless to the overall healthy functioning of our key biological systems. But what if, when you try to get back on the road, you find that you have a flat tire. Now the emergency continues (though it may look a bit different). When you get out of the car to change your tire, a hailstorm begins. You get the picture. What was just a moment of stress has become a stress that, at least for now, sees no end in sight (you have to wait for AAA, you are late for an important meeting at work, etc.). The longer the stress hormones like cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, which were released to get you to pay attention, are still coursing through your veins, your digestive, immune, and other regulatory systems will be put on a kind of hold, or worse, will begin to falter. This is what being under chronic stress does. It weakens us from head to toe.

Have you ever wondered why you finally get sick on the first day of vacation after a stressful period at work or why, after you finished your finals at college, you immediately collapsed afterward? At Ohio State University the husband-wife team of psychologist Janice Keicolt-Glaser and immunologist-virologist Ron Glaser wanted to see if their hunch was right that this kind of stress contributes to weakening the immune system enough to bring on the post-exam colds and sore throats and coughs that OSU medical students seemed to suffer from every academic year, like clockwork.56 So they enlisted medical students who would let them track them and they did this for several decades. What they observed was a predictable uptick in stress hormone levels and a disruption to the immune system that made students more vulnerable to viruses and infections.

In another fascinating 2013 study, Ohio State University researchers measured whether dwelling on negative events, in this case a bad job interview, increased inflammation in the bodies of healthy young women.57 The experiment was designed as a faux job interview. While each young woman (they were all in their thirties) did her best to pitch her talents, members of the “hiring” lab team sat in their starched white lab coats with their arms folded staring back at the young women and remaining expressionless and nonresponsive. (I get tense just thinking about it!) After the “interview,” half of the “job applicants” were asked to think about what had just happened and an hour later, their blood was drawn. The other “job seekers” (the control half) were asked to think about more neutral things before their blood was taken. The test samples revealed that the women asked to marinate in their stress had increased levels of C-reactive protein (which promotes inflammation and is associated with injury, illness, increased mortality, and poorer cancer outcomes),58–60 while the women who did not dwell on the stressful job interview showed no elevation of this inflammation-promoting, immunity-suppressing protein.

In terms of the effects of stress on cancer outcomes, in my own research I have found that kidney cancer patients who were more depressed and experienced more stress at the time of their diagnosis had a dysregulation of the stress hormone cortisol, as well as increased activation of key inflammatory gene pathways.61 Notably, these stressed kidney cancer patients did not survive as long as their less-stressed, less-depressed counterparts.

The Interplay Between Stress and Gene Expression

Earlier in the book I mentioned the groundbreaking discoveries in the new field of human social genomics, which studies connections between social and psychological factors and the way our genes function. So many facets of the great research that’s been done about how lifestyle affects disease progression comes together in this discipline in which we are now able to visualize the way gene expression—which controls the behavior of all cells and biological processes—is either positively or negatively influenced by lifestyle.

Steve Cole at UCLA is at the forefront of studying how long-term stressors, such as poverty, loneliness, grief, exposure to crime, or a diagnosis of a serious disease like cancer negatively impact our health in ways that go much deeper into our cells than most biologists (and oncologists) ever realized.62,63 What Cole has pioneered is an understanding of how poor health behaviors and psychological processes like stress and loneliness, while not so bad on any given day, can cause serious health issues to develop over time.64

Researchers working in this space know that long-term social behaviors contribute to illness and disease, but we also know that these negative influences can be changed and the damage they cause may be reversed or even stopped. I believe that this kind of reversal of fortune, if you will, is what we see in long-term survivors like the late David Servan-Schreiber or Molly M., Meg Hirshberg, Gabe Canales, and so many others. To help us make this known to the rest of the medical world, Cole has been mapping the function of genes, examining them against stress, loneliness, and other health behaviors.65 Cole notes that being able to do this is only possible because of the recent completion of the mapping of the human genome. Now researchers can pinpoint how specific genes react under the influence of specific external stressors. Now we can literally see how the outer world and inner world “dance” together to the beat of stress. This is a remarkable advancement in anticancer medicine. What Cole and others have now clearly documented is that chronic stress literally gets into our cells and increases aspects of gene expression making us more vulnerable to disease, while decreasing key gene pathways that help maintain our health and well-being.65 These genetic analyses have given new scientific legitimacy to studies that look at the biological impact of mind-body practices like yoga, tai chi, and qigong. In a 2014 study by UCLA researchers (including Steve Cole), a twelve-week yoga intervention was found to reduce inflammation-related gene expression in breast cancer survivors who suffered from persistent fatigue.66 Another UCLA study (also involving Cole) found that women with breast cancer who practiced tai chi for three months reduced their expression of genes related to inflammation.67 Similar beneficial genetic expression profile changes have now been documented with other yoga interventions as well as with qigong, meditation, and behavioral therapy programs.31,66,68

Resolving the Unresolved

What happens to us during childhood has an impact on our health later in life, particularly if our childhood experiences include high levels of stress and adversity. Research into the impact of adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, shows a direct relationship between high levels of childhood adversity and multiple diseases, behavioral problems, substance abuse and addiction, and obesity later in life.69–71

Here are the categories of ACEs as defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:72

-

Abuse

-

Emotional abuse

-

Physical abuse

-

Sexual abuse

-

-

Household Challenges

-

Mother treated violently

-

Household substance use

-

Mental illness in household

-

Parental separation or divorce

-

Criminal household member

-

-

Neglect

-

Emotional neglect

-

Physical neglect

-

If you have experienced one or more of these, you are not alone. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention teamed up with Kaiser Permanente to conduct one of the largest investigations of the long-term effects of childhood abuse and neglect ever undertaken. The CDC-Kaiser ACE study found that almost two-thirds of the more than seventeen thousand people surveyed reported that they had experienced at least one ACE.73,74 One in five reported three or more ACEs, with physical abuse and substance abuse being the highest. Meanwhile, an extensive health-related phone survey, also under the purview of the CDC, contacted more than fifty-five thousand people from thirty-two states and found similar incidence, with one in five people experiencing three or more ACEs.75

The latest research shows that exposure to toxic levels of stress, especially in young children, affects not only brain structure and function but also the developing immune system, hormonal systems, even the way our DNA is read and transcribed.76,77 Mounting evidence suggests a dose-response relationship between the number of ACEs we experience early in life and our risk of developing cancer, heart attacks and strokes, diabetes, and liver disease, as well as addiction, mental health problems, and behavioral problems as adults.78

Nadine Burke Harris, MD, has been at the forefront of the movement to educate the public about ACEs. She and her team at the Center of Youth Wellness in San Francisco screen every patient for childhood adversity and give them an ACE score to help assess their health in a more holistic way. In a study she conducted in 2011, Burke Harris found that, of the seven hundred patients she evaluated at her clinic, two-thirds had experienced at least one of the ACE categories. Children with an ACE score of four or more were thirty times as likely to have learning and behavior problems (compared with children with an ACE score of zero), and twice as likely to be obese.79

“One of the things I tell my patients, because of what’s happened to you, your body makes more stress hormones than the average patient,” Burke Harris explains. “We’re helping people control their stress response.”

In the same way an alcoholic reacts differently to alcohol, someone with a high ACE score reacts differently to stress and provocation, including a cancer diagnosis. In fact, numerous studies have found that breast cancer patients who had experienced childhood trauma reported higher levels of fatigue, depression, and stress and worse quality of life during treatment.80–83 What’s more, women with early trauma had decreased immune function, increased inflammatory markers, and heighted expression of genes linked with inflammation. What that means in terms of cancer prevention and survival is that for those who have a lot of childhood stress, adopting and sustaining a mind-body practice and creating a safe and supportive network could be the most important component of their anticancer lifestyle.

“There’s no pill,” Burke Harris explains. “If you had an ACE childhood, your stress response will fire faster and harder. There’s never a time when someone is like, ‘Oh, that’s completely over and done with.’” In her recently released book, The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity, Burke Harris provides a prescription for dealing with toxic stress. It’s not over, but it can be managed and mitigated.

Michelene H., whom you met in the last chapter, is one of the one in five people who have experienced three or more ACEs. As a child, Michelene experienced emotional and physical abuse, emotional and physical neglect, and the divorce of her parents. After leaving home at sixteen, and taking many turns in the road, Michelene realized she needed to address these past issues if she was going to be successful in maximizing her health. It was a long journey for her to get to where she is today: the only child in her family to have graduated both high school and college, and feeling healthier than before she had breast cancer. As she put it: “I ultimately came to terms and realized that although I was abused that didn’t mean I had to live like I was abused, and I definitely wasn’t going to abuse my children.” Coming to terms with these early life experiences took time, but she had to address the issues head-on to achieve the health she feels today.

Bad experiences, like bad habits, have a way of catching up with us if they aren’t addressed. While our tendency can be to ignore or deny things that are too hard or painful, moving toward an understanding of what has happened to us as children is important work for our health.

Cultivating a Positive Frame of Mind

Having a positive mind-set is uniquely and intimately tied to our ability to build a healthier community, but doing so requires a complete 180 from our evolutionary past. In early humans, being aware of and avoiding danger was a critical survival skill. But research shows dwelling on the negative is bad for our health and works against our efforts to build a sustainable and sustaining anticancer lifestyle.84,85 Our natural tendency is to make decisions to avoid negative consequences. We are more influenced by negative news than by positive events, and we see people who say negative things as smarter than those who are positive. Research also shows that when we are not engaged in a task, our idle mind tends to focus on the negative, either past or future, and be in a state of “worry.”86 An excess focus on the negative can stimulate the stress response and trigger physiological inflammatory processes.87 In addition to affecting our health, our mind-set and outlook impact our ability to utilize social support and build friendships and relationships based on trust and compassion. Being empathetic starts with recognizing and believing in your own self-worth. Believing in yourself means seeing and appreciating the good all around you, which in turn makes you happier, easier to be with, and more likely to form stronger, deeper connections with others. Growing your anticancer team begins with the attitude you are projecting knowingly and unknowingly to others.

When she left the hospital after her second brain surgery, our friend Molly M. began a year-and-a-half course of the first new brain cancer medication to be approved in North America in more than twenty years. She told her doctor she would stay on the drug until either she or the cancer died. She used an electronic stimulation treatment called AccuTherapy to boost her white blood cell count so the doctor would allow her to continue receiving chemotherapy, and she worked hard through all of this to cultivate a positive frame of mind. Her father made positive affirmation index cards for her to flip through, and Molly put sticky notes around her house—on drawers, mirrors, cupboards, the fridge. They weren’t platitudes like “Keep smiling” or things like that. Instead, they conveyed positive, meaningful messages to remember, like, “You are healthy” or “This illness is not you” or “Be positive,” which were direct challenges to the cancer and to the awful side effects of treatment Molly was trying to manage. As she explains, “I didn’t have any illusions—nor did I want them. I wanted to stay grounded in reality, in life. I wanted to get my balance back (it’s really knocked out of you when you have brain surgery) and figure out how to stay balanced. I had to figure out how to build up a sense of hope so I could do the hard work of educating myself and finding ways to get out from under the awful stress of the disease. So I just started eliminating all the external stress I could, which included things like watching, listening to or reading the news, which just made me feel lousier than I already felt.” The notes were a way of redirecting her thinking and keeping her mind away from the kinds of thinking loops that can lead to anxiety, depression, or despair. In addition, she developed and religiously maintains a daily mind-body practice that centers her and enables her to feel sure of her path.

Cultivating Gratitude

One of the ways we can move from negative to positive thinking in our daily lives is to focus on what we are grateful for. Research shows that gratitude, like a lot of what we traditionally think of as “just in our heads,” actually has a measurable impact on our physical and mental well-being.88 In one 2003 study, researchers at the University of California in Davis had subjects write a few sentences each week. One group focused on things they were grateful for, a second group focused on things that irritated them, and a final group focused their writings on experiences that had neither a positive nor negative impact.89 After ten weeks, the group that focused on gratitude reported increased optimism and self-confidence. Members of the group also reported that they exercised more and made fewer trips to the doctor.

I tried a variation of this experiment myself a few years ago. I have to admit that I initially found this exercise both difficult and frustrating. I realized that as an academic and scientist, I had actively trained my brain to focus on the negative. I spend my days searching for problems that need to be solved, either in studies, grants, or papers or some bad outcome that needs to be addressed and researched. It took real effort on my part to tune in to another side of things, which was in fact happening all around me. And the struggle paid off in ways I had not anticipated. As I continued, day after day, to recognize and record positive exchanges—strangers helping each other on the street, my colleagues laughing in the hallways, my kids being nice to each other—I found I was able to tune in to the good all around me, and my own behavior and outlook started to change.

One of the lead researchers in the ten-week gratitude study, Robert Emmons of the University of California in Davis, has gone on to compile a list of health data points from his own study and from other research related to gratitude. Research has found that actively practicing gratitude lowers the level of the stress hormone cortisol and reduces inflammation, two biomarkers linked to a variety of diseases, including cancer.90,91 Studies also show that gratitude reduces depression and improves sleep quality.89,92,93

How Managing Stress Allows Healing to Begin

Like Jon Kabat-Zinn, psychoneuroimmunologist Mike Antoni, PhD, is at the forefront of finding ways to not only study how stress impacts our health but to come up with stress-management plans that can help us stay healthy and calm, even in the face of trauma and disease. For decades Antoni has led a research team that conducted a series of randomized trials that assessed how well breast cancer patients who engaged in CBSM (cognitive behavioral stress management) training in the early stages of their treatment fared over the long term.94 The training included teaching relaxation skills (such as muscle relaxation and deep breathing) and techniques to reduce negative thinking. These were taught in weekly group sessions for a ten-week period. Antoni wanted to test whether this stress-management program could improve quality of life, impact biological processes, and decrease the risk of disease progression and mortality over the long term. And indeed, patients who participated showed increased survival rates and longer periods of remission at an eleven-year median follow-up.95 This research shows that learning to effectively manage stress improves stress hormone regulation, immune function, and, more recently, gene expression, showing a down regulation in genes controlling inflammation and up regulation in immune function genes—all of which help to keep the metastatic process in check.96

Additionally, the CBSM participants reported improved quality of life and lower levels of depression and anxiety than those in the untreated control group, and these positive benefits held over the long term as well.97

What is so thrilling about this research, in terms of its application to anticancer living, is how long lasting the impact of early stress intervention is on the long-term survival and quality of life of these cancer patients, and ongoing studies suggest that this will be the case for everyone who engages in stress management.

Anticancer Living Begins When Stress Ends

The presence of stress undermines our good intentions and efforts to eat properly, rest well, exercise adequately, or make other health-enhancing changes, the most important being to improve our overall sense of satisfaction with life. Not only does stress inhibit our ability to do the right thing, it tends to trigger us to do the opposite, such as drink too much, or smoke, or lose our temper, or turn away from those we love.98,99

Stress will literally sabotage all our healthy intentions. If you come home from work stressed and exhausted, you are less inclined to spend the time chopping vegetables. Stress puts you in the position to say, I’m not going to exercise today, or let’s go out for pizza. It can also keep you up at night, further jeopardizing your health by reducing your sleep.

Newsflash: Stress Cancels Dietary Benefits!

Here is an example of how stress can sabotage our good intentions around healthy eating. A team at Ohio State University found that prior-day stress eliminated the differences in biological response to eating a meal with high versus low saturated fat.100 In other words, if stress was not managed, it didn’t matter what people ate—the effects of healthy and unhealthy food was the same. All the women in the study, thirty-eight breast cancer survivors and twenty noncancer participants, ate a meal high in saturated fats and on a separate day ate a meal low in saturated fats. From blood samples drawn multiple times during the study, researchers examined two inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and serum amyloid) of cell adhesion that are linked with plaque forming in the arteries, fat and carbohydrate oxidation, insulin, glucose, and triglycerides as well as an interesting measure assessing resting energy expenditure (how many calories you burn just resting).

Their first finding was that having experienced more stressors on the previous day resulted in lower post-meal resting energy expenditure, lower fat oxidation, and higher insulin levels.100 For women who did not experience any stressors the day before their meals, the high-saturated-fat meal led to increases in the inflammatory and cell adhesion markers, while the low-fat meal did not. But for the women experiencing stressors the day before, there were no differences in their body’s reaction to the meals. They had the same heightened inflammatory and cell adhesion markers after both meals. In other words, their body’s response to the healthier meal was the same as if they had eaten the unhealthy meal.100 The link between stress and diet in this study suggests that stress modifies metabolism in ways that may promote obesity and increases inflammatory responses, no matter what we eat. That is why stress management comes before diet and other healthy changes. If you don’t control your stress, your other lifestyle improvements may be in vain.

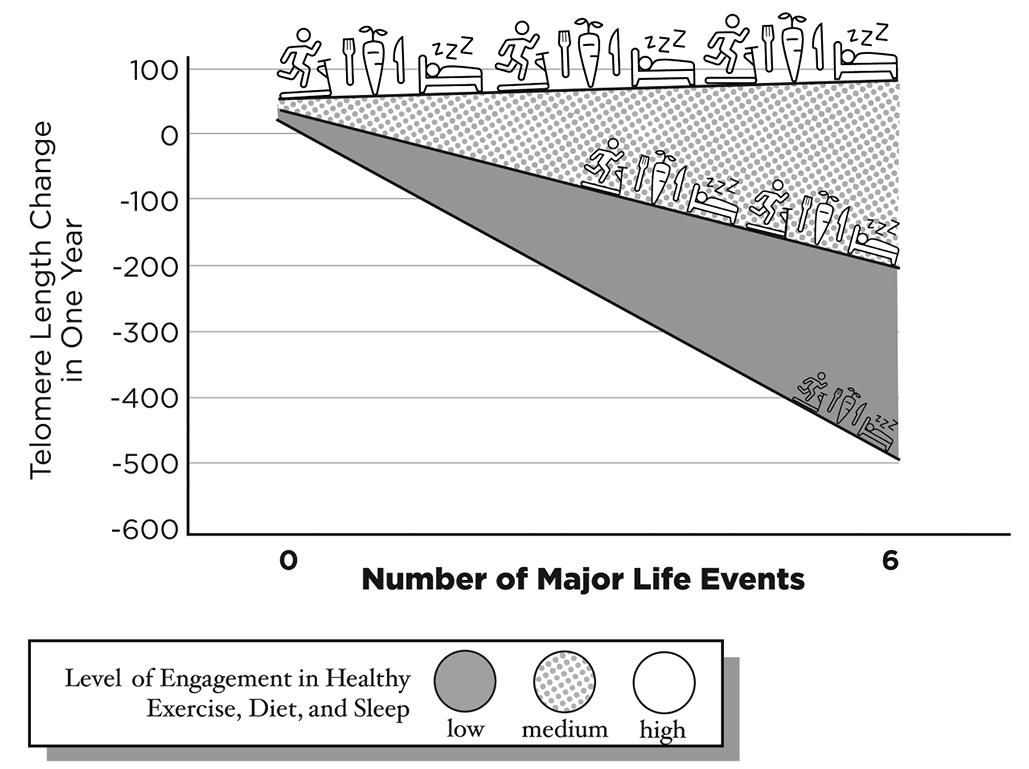

Yet we also see that lifestyle factors can reduce the harms of stress. A 2014 study found that women who maintained a healthy lifestyle were protected from the effects of stress on their telomere length.101 The study, which Epel and Blackburn participated in, looked at telomere attrition in 239 postmenopausal women over a one-year period and found that stress-induced telomere shortening was reduced if women engaged in healthy behaviors, including a plant-based diet, regular exercise, and adequate sleep. This study replicated previous studies showing that healthy lifestyle buffered stress and was associated with longer telomeres.102–104

Healthy Diet, Exercise, and Sleep Defend Against Stress-Induced Telomere Shortening

Although the study found that across the course of a year the more major life events someone had the shorter their telomeres, healthy lifestyle reduced stress-related telomere shortening. The line on the top represents the women who engaged in a high level of healthy behaviors of exercise, diet, and sleep. Regardless of the number of major life events, their telomeres remained unchanged. However, for those engaging at a medium or low level, as the number of major life events accumulated the greater the telomere shortening.

Adapted and reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: E. Puterman, J. Lin, J. Krauss, E. H. Blackburn, E. S. Epel, “Determinants of telomere attrition over one year in healthy older women: Stress and health behaviors matter,” Molecular Psychiatry 20, no. 4 (July 2015): 529–35.

Adapted in collaboration with Laura Beckman.

We are beginning to see how important it is to control stress, both in terms of its direct impact on our health and in terms of its indirect impact on everything from sleep to diet and exercise. The research points to a critical need for all of us to take time every day to relax and separate from the demands and responsibilities of our lives. Being in the moment, even for just a few minutes a day, can change your outlook and dramatically impact your health. Reducing and managing stress is key to your success in changing your life in other areas and maintaining those changes over time.

How you choose to reduce the chronic stress in your life is, like all aspects of anticancer living, largely up to you. When you tune in to your intuition and listen to what your body needs, you may surprise yourself by realizing that you no longer care to be triggered and stressed-out by following the news or by seeing pictures of the charmed lives of your friends on Facebook. You may realize it’s finally time to quit the job that’s draining your energy, give up the low-quality diet that makes you feel so uncomfortable you can’t sleep at night, or you may decide it’s time to end an unhappy marriage or relationship. Or, if you are like most of us, you just need to learn how to unwind and experience a kind of peaceful easiness that eludes too many of us in this go-go world we live in.

I know for myself, I used to equate being under massive amounts of work stress with somehow being more committed or more successful than the next guy (yes, I realize this makes no sense at all), but I was wired with a fear that if I stopped, I’d somehow not be able to do my job as well or I’d somehow get left behind in the highly competitive world of cancer research. It took me a long time to make a commitment to be less motivated by stress (and fear) and more by the health benefits I’d reap if I slowed down. Little did I know that taking care of myself would not only relieve me of work anxiety but also make me more productive and focused despite my putting in fewer hours at the lab.

The Joy Protocol

Diana Lindsay is someone who has grown uniquely attuned to her mind, body, and spirit. But she tells me it was not always this way. “When I was first diagnosed with cancer, I had no idea how to heal myself and neither did my doctor,” she explains. “One night, right after I got the news that I had stage IV cancer, I had a dream, and the next morning I invited all my friends to come over to our place. On a practical level, I didn’t want to have to call each one and tell them I was sick—that just seemed too difficult. So my friends came over and we sang and danced and laughed and just had so much fun. It certainly wasn’t a wake or anything like that. It was just a bunch of people I love getting together and getting really joyful. The next day, when I went in to find out my treatment options, I asked, ‘What about the joy part?’ I wanted to know because despite being so sick, I still clearly had a capacity for joy. I became determined to follow what I think of as my joy protocol. I researched what happens to your body when you feel intense happiness and I found out you get a great hit of endorphins, oxytocin, and dopamine—all are natural chemicals in the brain that make you feel good when you can let go of your worries and just be joyful. Then I found out that these substances all stimulate the immune system. So I got really serious about seeking out joy wherever I could find it. I’m certain this has been a major component of why I’ve defied the odds for so long. It’s hard to keep someone who is enjoying life down.”

Lindsay’s embrace of her situation and her determination to find joy in the face of cancer exemplifies the goals of anticancer living. This is why it is so important for all of us who work in integrative oncology to address the psychological and emotional realities of cancer diseases and help patients develop the kind of mental and emotional resilience that will foster their healing. When we focus on reducing stress, then worry and fear are replaced by a sense of calm and often a renewed sense of appreciation for the beauty and joy of life.