The Falconry Centre was started in 1966, opening to the public in May 1967 (in 1990 the name changed to The NBoPC). My father had talked about starting a centre for years and finally, encouraged by my mother and the rest of the family, decided to have a go. I had left school and so was available, and interested enough, to help full time. We moved up from Dorset in November ‘66 with twelve birds. We still have one of the original inmates, a Common Buzzard called Pete. She is on loan with a friend of mine in Derbyshire and for those of you with older birds, don’t despair; at twenty-one years old she produced her first babies and hatched and reared them as well—not bad for an old lady! In those days, with no import restrictions, birds were easily available and by May 1967 we had about sixty birds. Martin Jones, now well known for his equipment (falconry wise) was at Cirencester Agriculture College at the time and used to come over regularly, collecting new arrivals at Gloucester station and helping out generally including building pens. He eventually ended up working here for some considerable time.

We used to get the oddest birds arrive here, who very often turned out to be nothing remotely resembling what had been advertised, and sometimes not even coming from the right continent. Some arrived in the most appalling condition and it took a great deal of time and effort to get them right again. One bird arrived in an old orange box. He was supposed to be a Roadside Hawk from America—she turned out to be a Yellow-billed Kite from Africa. She had been kept in heaven knows what, and had not one single feather on her wings, just bloodied flesh and bone. Needless to say she stayed, as did they all. She was put on jesses and placed on the lawn in the warm sun and offered a bath. She was very tame. About ten minutes later on checking her we noticed that she looked as if she was sitting much further away from the block than the leash length should have allowed—she was. There sitting next to her were the jesses, still complete but with no bird’s legs in the straps. We tried twice more to keep jesses on her and then gave up. She couldn’t fly and having quickly sorted out all the dogs and established that she was definitely boss she ambled about the garden and took up residence in the greenhouse. There she stayed with regular sorties about the garden until finally, two years later, when she had regrown all her feathers and started to get a little too adventurous, we tethered her in case she went near one of the trained eagles and got eaten for a quick snack. She is still with us and lives in one of our old pens with three other Yellow-billed Kites; all of them are females and they are all due to have a smart new pen one day, so that they can continue to lay hordes more infertile eggs.

Although her story ended well, we were generally quite pleased to see import restrictions come in, as many of the birds we saw were very sad cases indeed and often did not survive. I often wish that we had had the experience then, that we have now, as we would have been able to save more and would, I am sure, have bred from some of them. Many of the species that came in have subsequently become rarer in the wild, and we could have already achieved some valuable work with them had we had more knowledge.

By pure luck we have built up the whole collection slowly and so have learnt how to look after large numbers of birds without having a sudden influx. When you are caring for livestock that, in many cases, you only see for a very short period twice a day, you have to be able to look at the individual birds and say to yourself, ‘That bird looks fine, all is well in the pen, it took its food well and the pair are getting on fine with one another, therefore I should not need to worry about them until they are checked again in the evening.’ Many people may not even be able to check their birds twice a day in daylight hours during winter, and so even more experience is needed. We find that we ‘listen’ to the birds a great deal. Little or no notice is taken of the normal noises they all make, other than to note that they are making them, but if a noise that we don’t normally hear is made, we will stop and listen and maybe even run like stink if we think we might have a problem, such as the occasional matrimonial tiff.

The original ideas behind the Centre’s beginnings were to use the increasing interest that people seemed to be getting in birds of prey to get them to visit the Centre, and learn about the birds. At the same time we wanted to try to breed the birds in captivity and preferably, if possible, in front of the visitors. We also had to live, so the whole thing had to be a viable concern and support itself. I don’t know, as they have never told me, but I am damn sure it did not support itself to start with, and my parents had to fund it until the time came that the Centre could stand on its own two feet. It barely does that even now.

These values behind the Centre have not changed a great deal. I am slightly less interested in the falconry aspects than my father. The side of the Centre that interests me most—and the side we have developed—is the breeding, conservation and education, although I thoroughly enjoy flying birds and hunting them. I have however, very little time these days, and flying birds for demonstration, for as long as I have, has dulled the interest slightly. I am looking forward to a winter when all is complete here and I have nothing to do, then I will enjoy my falconry again. I think I may well be rather old at that point.

Vultures, often thought of as unpleasant and ugly, can be very beautiful when seen at close quarters

At first the Centre’s plans for breeding raptors in captivity were laughed at by many people. Although zoos had occasionally bred birds of prey and so had some falconers and aviculturists, their success was rather more by accident than design (I am glad to say that this is no longer the case). To set out to keep a specialist collection of birds, nothing but birds of prey, to interest the public enough to pay to come and see them, and to breed from the birds was a pretty brave thing to do, particularly as none of us had much experience in either dealing with the public, coping with large numbers of birds, or trying to breed from them. Still, as can be seen today, the idea was not quite so far fetched. To date the Centre has bred more different species of birds of prey than any other single establishment, and many of those species have reared their young in front of the public. We have had hundreds of thousands of visitors over the years that we have been open, and most of them have left better informed about raptors than they were when they arrived. We have also learned a tremendous amount about birds of prey and about captive breeding in the intervening years.

Twenty years ago birds of prey were not viewed in as pleasant a light as they are today. Nowadays most gamekeepers no longer see them as so great a threat that they shoot everything that has a hooked beak, as was the case not so long ago. Fewer people are convinced that eagles kill sheep and steal babies out of prams; although how that idea came about I would love to know, as I can’t think of anyone I know stupid enough to try and push a pram over the sort of terrain that eagles inhabit.

Raptors, however have always been thought of as red in tooth and claw and many people still envisage them with powers far greater than they actually have. Gentleness is not a trait usually applied to raptors and yet to watch an eagle or hawk feed its young is a wonderful sight. The care and patience these great birds have with their babies is fascinating to watch and this is what we want our visitors to experience, thus showing them a side of birds of prey which few people have the chance to see, and which puts the birds in a very different light.

We have always tried to fly the birds at demonstrations for all our visitors, only the weather or emergencies stopping us. The demonstrations have been one of the things which has made the Centre so popular and they have a very important educational value if done well. However I stress the ‘done well’ aspect. Numerous people now fly raptors for the public and, although many are very good, sadly there are others who do not always do the job well. I am always keen to point out that it is very much a demonstration rather than a display. All we attempt to do at the Centre is demonstrate either the different ways in which different species and family groups fly, or the training methods we use. It is not a circus act, nor should it ever be. The birds are only asked to do what comes naturally to them and this is very important. I suppose its equivalent would be a gundog demonstration, where much the same thing is happening. The dogs are behaving in the way that comes naturally to them. That natural talent is harnessed, and the training methods are shown.

Some of the working birds at The National Birds of Prey Centre

Tremendously valuable work can be done with good demonstrations. I feel very strongly that I would much rather show my visitors trained birds, flying well and naturally, and if I have done my job well, in a spectacular fashion, under controllable circumstances, than I would see millions of people wandering around the countryside disturbing wildlife in an attempt to see birds of prey in the wild. So this is one of the main reasons for flying the birds here for our visitors. The birds are great public relations men (and women), and given the chance to be in front of visitors they manage to do most of our teaching work themselves! However, here at the Centre we do not allow visitors to handle or fly the birds. The reason for this is that I believe it is all too simple for people to think that the whole art of falconry is very easy. It is easy to hold a bird that someone else has got tame, while they are standing by to help you, but it is a very far cry from training a bird from scratch and so I prefer to keep the birds a little removed from my visitors.

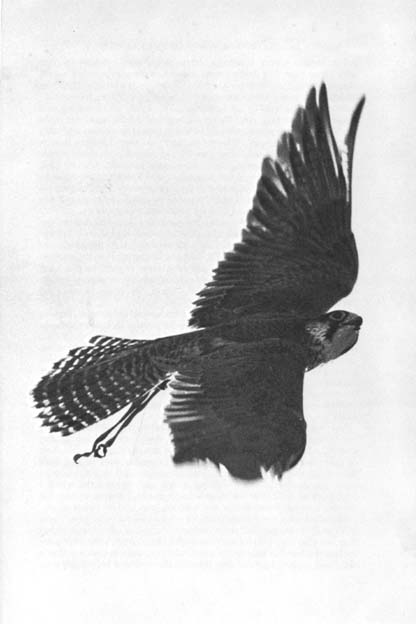

If done well, with the right commentary, flying demonstrations can be very educational

Having said that, we have from time to time had parties of blind children visit us here. This can be very exciting and, although extremely hard work, is very rewarding. In these cases we have a few birds that can be touched and handled by strangers, and we allow this handling of the calmer birds by the blind children. You have to have very steady birds though, as the children really do touch quite roughly to find out about them. We try to get the parties to visit at the right time of year for us to have baby birds available, so they can touch and feel the young. We also give them large eagle feathers to wave through the air to get the feel of the power of flight—within seconds the whole place is in chaos with feathers beating the air, waving up and down everywhere. We even fly birds for the children as they can hear the bells and the noise of the birds’ wings through the air. If we fly a falcon we know we can direct accurately, the children get very excited feeling the bird fly close over their heads.

A letter from enthusiastic young visitors

All this is very much part of education, and education to us is one of the most interesting aspects of conservation, and probably the most important for the long-term future of birds of prey and all other species. If the right birds are used and the right message is put over to the audience, having a trained bird that will (hopefully) return to you, is a first class visual aid to an educational programme. The length of time that people remember the experience is amazing. I don’t know about you, but I can’t remember any of the lectures or outings we had at school. Come to think of it I do remember being coach sick somewhere in the New Forest, but that is by the by. We have visitors here who tell us how they remember my great uncle talking to them and flying a Golden Eagle at their school. They even remember the bird’s name, Mr Ramshaw. This shows how much of an impact the experience of a live bird had on them. People who think that lectures with live birds will encourage falconry, and the illegal taking of birds, will be delighted to hear that not one of those visitors who have spoken to us and saw Mr Ramshaw, ever took up falconry.

Of course things don’t always go quite as planned during flying demonstrations. In 1976 I managed to lose three birds in one summer. It was a particularly hot one, subsequently we learned how to fly birds in hot weather. I lost one of them at a show away from home, which would not have been quite so bad had I not been wearing medieval gear, and looked like a complete pratt. That in itself would have been okay if I had not been trudging through strange farmers’ fields, slowly melting from the heat, and getting some very odd looks from those who saw me! At least if we have a bird go absent without leave at the Centre we can usually fly another one, but away from home I rely on my ‘away team’ and if things go wrong it can get embarrassing. It is not always my fault though. I have ended up in the ring swinging a lure to three microlight planes that were doing their demonstration above me, having started far too early. In the meantime my falcon was flying about half a mile away, wondering what the hell was going on. Several of my top falcons go a very long way up before returning, and can be out of sight for some time. I have to admit that I once spent twenty minutes swinging my lure to a seagull which I thought was my falcon—it did not come down to the lure.

We have our critics. Many falconers accuse us of being commercial because we are open to the public and sell some birds for falconry. I suppose they could be right, but what they probably don’t realise is that if we were totally commercial we would not be open to the public as this is very expensive. Most of our staff are here to cope with some aspect of dealing with visitors without whom we would only need to employ one person just to look after the birds, rather than up to twelve staff during the summer. The car park, paths, loos, etc etc have all been built solely for the public, as have play areas, seating, and numerous other facilities. We could, without doubt, make far more money with far fewer overheads by being closed to visitors and only breeding birds for sale. However we don’t do that. I believe that as we have this collection of birds, we should share it with those people who visit us to enjoy seeing the birds as much as we do. Also we have a responsibility to pass on our experience and knowledge in order to assist both the birds in the wild and those in captivity. Falconry would be a lot poorer without people prepared to stand up for it, and not keep a ‘low profile’ hoping that all problems will go away.

A Lanner, flying well

We are also criticised by some bird societies who feel that we encourage falconry. Those societies don’t approve of birds in captivity. I think that any harm we might do is far outweighed by the good, particularly on the educational side, and not forgetting that the number of species world wide now relying on captive populations to keep them from extinction is increasing every year. So, in spite of critics, the Centre has continued up to the present day and will continue, improving all the time.

When the first pens were built there were several constraints, finance being the main one (and still is to this very day); lack of experience being another. No one knew what sort of pens the birds would like. Now we have a far greater knowledge and are rebuilding all the time. Another problem we didn’t understand was that you don’t just build pens to keep the birds in, you build them to keep the public out. For example, there are very few fences, none we can afford to put up at the moment, that will stand being sat on, leant against, climbed over, walked along and subjected to any other abuse you can imagine (and some you can’t).

Very tame birds can be a danger to themselves. I remember walking round the corner in the aviary area one day to find a man poking a stick, which he had broken off one of my shrubs, into the chest of a particularly tame Serpent Eagle, who was looking at him with the utmost disgust and disdain. I didn’t say a word to him (surprisingly) but happened to be walking with a stick in my hand which I proceeded to poke into his chest—fairly gently, I hasten to add. He got the message immediately and nothing was said by either of us.

We often have tame young owls in what I call the baby pen. These will run up to people near the wire front and gently nibble fingers, but they are also very playful and somewhat destructive. One afternoon we heard a howl of misery from the baby pen, only to discover that a child had pushed a pound note through the wire at a baby eagle owl, who had quickly removed it from his fingers, dashed to the back of the pen with glee, and was proceeding to tear it into small and unusable pieces. I thought training a bird to do this might be quite a good way to fund raise, but we rescued the loot and returned it to its rightful owner, who promised to be more careful in future. We did not forget the owl, who was given a less expensive piece of paper to demolish.

Believe it or not, all this sort of thing, and the many other interesting and amusing happenings, are a valuable experience to the visitor. I am delighted to say that I think most leave the Centre having had an enjoyable day, learnt something without feeling lectured at and having a better impression of birds of prey. Few will forget the experience of having a bird fly close to them and many will treasure it for the rest of their lives, and this is the whole point of The National Birds of Prey Centre.

Falconry as a career!

One thing I would like to say early on in this book, please think hard before you decide you want to take up falconry as a career. There are no careers in falconry. There are a few jobs available in things like clearing rubbish dumps with falcons, but this is generally unsuccessful, as is clearing airfields, unless it is done properly, using the right birds for the job. One of my staff actually worked on rubbish tip clearance and seemed to spend all his time hitting tin lids with sticks to frighten the crows and gulls away—hardly falconry. Very few people employ someone to be their falconer; I know of only two in this country. Most people interested in falconry do all the training and flying of their birds themselves.

We have many letters each year from people who have visited the Centre, seen similar establishments, or watched us on the television. They ask for jobs because they are interested in falconry or birds of prey. The job we do here is not falconry. In fact, we probably have far less time with the birds than most falconers who are just flying their own birds as a hobby. The only time we have to handle the birds is during the demonstrations, and, as already mentioned, even that palls after a while.

All my staff will tell you that I am so mean, I don’t give them enough time to hunt birds properly, especially during the winter months, when all available daylight hours are used in building, care and maintenance. Most of the time we are either mowing lawns, cleaning loos (great job that one!) raking compartments, cleaning up bird droppings from night or sick quarters, or dealing with the visitors. None of which is tremendous fun after a while, and none of which really relates to falconry. If you are interested in taking up falconry, then for heaven’s sake sort yourself out with a job that gives you plenty of daylight hours, and take it as a serious hobby. You will enjoy it far more, as everyone here can tell you from great experience. And don’t think that places like this are going to teach you falconry with you working for them on a volunteer basis for nothing, because very few places have the time, and they may be running falconry courses commercially in which case you can hardly expect to be taught for nothing.

The National Birds of Prey Centre has one of the largest collections of birds of prey in the world and we hope to increase it slowly as we go along. Each species we succeed with means that if it needs help in the future we are already, by sharing our hard learned knowledge, a long way along the road to assisting it. Each species that we can teach visitors about is a little extra knowledge disseminated, all of which helps in the long run.