Chapter 9: To War with the Marines

“If the Army and the Navy ever look on heaven’s scenes,

they will find the streets are guarded by United States Marines.”

– The Marines Hymn

Training with the India Company Marines in the field at Twentynine Palms meant understanding their SOPs—Standard Operating Procedures. I quickly learned where to sit in my assigned vehicle when on the move and where to throw my gear when we stopped. I was part of the company headquarters element, which included the Company Commander, Capt Benson; the Executive Officer, Lt Riley; the First Sergeant, 1stSgt Haley; and the Company Gunnery Sergeant, GySgt Romero, as well as the Weapons Platoon Commander, Lt Patrick Kelly, and various radio operators and navy corpsmen. As part of this group, I needed to stay close to Capt Benson—without getting in the Boss’s way.

An important Marine SOP was the daily shave. This created a problem as I’d purposefully grown a full beard to fit in better with locals when we got to Afghanistan. When Capt Benson asked me about it I explained that Afghans think a clean-shaven look is ugly and they consider hairless westerners weird. Islam sanctions facial hair as a sign of manhood, respect, honor, and righteousness. They take their cues from holy sources: Mohammed, Jesus, and the prophets all wore beards. I’d connect better with Afghans if I looked like them. So Capt Benson gave me a waiver.

As the hot summer days went by, I got more and more comfortable with the India team. Early each morning we’d mount our vehicles and head out to yet another training area—bouncing through the desert in our trucks and Hum-Vees. Some of the training was purely tactical—small unit operations on the platoon and squad levels, where there wasn’t a role for me. My job focused on the civil affairs training scenarios involving noncombatants. As the platoons rotated through those scenarios, I got to know Marines from throughout the company.

My uniform was the same MARPAT digital camouflage desert utility garb worn by Marines, except for the missing Eagle, Globe and Anchor insignia that can only be earned at a Marine Corps boot camp. My name tag read “Hollywood” instead of “Fazli”—a tag the Boss thought would protect me since the Taliban targeted interpreters and their families in Afghanistan. Unlike the local families of Afghan interpreters, or “terps” in Marine Corps shorthand, my wife and child were presumably safe in Dana Point. Still, given that I was fairly well-known in the Afghan-American community and that there were presumably some Taliban sympathizers in southern California, the thinking was “Why invite trouble?”

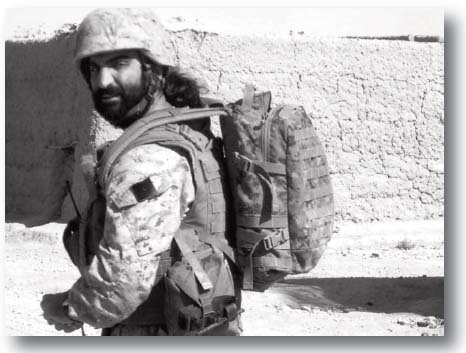

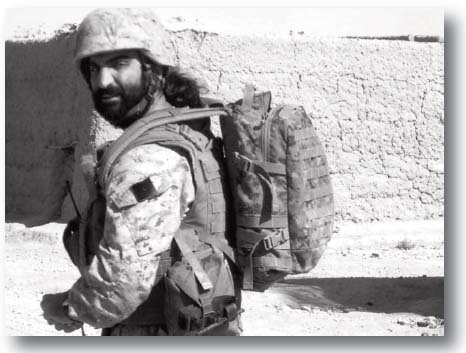

Fahim in the field

It was beyond hot at Twentynine Palms—around 110 degrees. However, the Marine units in Afghanistan were deployed in the country’s southern desert, where temperatures of 120 degrees were common in the summer. We received regular reports from Afghanistan about Marines suffering from heat exhaustion in Helmand Province. The required helmets and body armor just trapped heat around bodies. We needed to drink lots of fluids and plan for access to adequate water supplies. Overheating made people careless and erratic, putting their lives—and missions—at risk.

Southern Afghanistan’s intense summer heat often made it too hot to fight, for both coalition and Taliban forces. Heat exhaustion routinely sidelined infantrymen who patrolled during the day, so British and American forces often moved in the dark. aided by night-vision devices. The Taliban couldn’t compete with that technology, so they largely limited their summer activities to placing IEDs and occasional sniping.

Fortunately, 3/4 would be in-country from October through April and would miss the worst of Afghanistan’s summer temperatures. We wouldn’t have to contend with the infamous “Wind of 100 Days” where the extremely high temperatures so warmed the earth that convection currents created hurricane force winds whipping up sandstorms of biblical proportions, restricting almost all movement or outside activity. While we’d miss the intense summer heat, we would arrive just in time for the fighting season.

Operation Mojave Viper was designed to prepare Marine infantry battalions to work in the Afghan desert. Some of the training scenarios required us to engage “native” Afghans in mock villages. That’s where I came in. The natives were actors—mostly Pashto speakers—who’d been assigned certain roles. My job was to communicate with them and interpret for Capt Benson.

A week into training, in a particularly realistic scenario, two Afghan men from different tribes started screaming at each other. They were actors, but I still thought they might kill each other over some notional dispute in a mock Afghan village street. LtCol Wetterauer—Darkside 6—got involved and approached the scene with a couple of well-armed Marines and a terp. Their presence immediately diffused the situation. It didn’t hurt that Darkside 6 himself had a pistol in his holster. He separated the antagonists so they could cool off and then spoke to them individually. He found some common ground and promised to take action. I was impressed. This is what we needed to do to succeed—communicate and bring people together.

Interpreting meant more than just converting Pashto to English, and vice versa. Many of the role-players were native Afghans and we needed to properly interpret cues and cultural signals. A simplistic misconception on the part of some Marines, for example, was that the Taliban wore black turbans and friendly Afghans wore white ones, like in Hollywood cowboy movies. In reality, anyone might wear a turban of any color. Sometimes body language and demeanor indicated political mindsets. Smiles were good. A failure to look you in the eye was bad. If someone relaxed after talking with me a while—that was good. If they continued to be nervous—that was bad. And just because someone claimed he didn’t know anything about the Taliban didn’t necessarily make it so.

We spent considerable time discussing how to deal with native Afghanistan women in a culturally conservative region. I began one evening lecture in the desert by stating, “Dealing with women in Afghanistan can be complicated.”

A sergeant interrupted me. “Dealing with women in America can be complicated.”

Everyone laughed.

“You’re likely to see very few women,” I explained. “And if you do see any, keep a respectful distance. Don’t try to talk to them. They’ll probably be fully covered by blue burquas. An exception could be poor widows. If you see some older women in black outside begging, then it may be OK to give them money or certain types of food.”

“What if we have to clear a building and there are women inside?” asked Lt Riley.

“Good question,” I replied. “Keep your distance from them. Hopefully a terp like me will be around to help. If not, then use words and gestures to get them into a room that is not being searched while you’re securing other places. Then move them into a cleared space when you need to search their room. Ideally, we’d have female terps, but those are few and far between.”

I anticipated playing a significant role when it came to Afghan women. It was hard enough to get male terps to work with Marines, much less female terps. The USMC was frantically trying to get women Marines trained in Pashto, but that would take time.

Bilingual native women would have been ideal interpreters. Unfortunately, they were rare and better suited for all-female engagement teams than to be embedded with infantry battalions.

“Don’t the women leave their mud huts to buy groceries or clothes?” asked Staff Sergeant Cooke.

“Not necessarily,” I replied. “You’ll find men selling women’s lingerie to other men in stalls at bazaars.”

“I guess we know where Luffy-Lips will be spending his spare time when we get there,” said Cooke. The Marines laughed and all heads turned towards an embarrassed lance corporal.

Humor aside, the Marines were now thinking more like Afghans. The training evolutions at Twentynine Palms were well-thought-out and really tested India Company—and me. We returned to base camp much more confident about operating in Afghanistan.

While born of the Barikzoy Tribe, I now felt like I was part of the Marine Warrior-Tribe. Since Afghanistan is a tribal land with an embedded warrior culture, I assumed Marines could fit in well there if they did the right things to connect with the native Afghans, and not alienate them, as the Soviets did. Americans tend to appreciate people as individuals. Afghans take mental shortcuts by assigning commonalties to whole groups of people—to whole tribes. The Marines were tribal in many ways. They wore the same uniform. They shaved every day. They had their own jargon. They treated their weapons with great care. They were loyal to each other. They projected strength and confidence. Color was of no consequence. You could be in the Marine Tribe whether you were white, black, yellow, or red. Afghans later found this dynamic curious and interesting, especially when they sensed that I, an Afghan, was of the Marine Tribe as well.

It was unfashionable to say that we sought to win Afghan hearts and minds, as that brought up uncomfortable memories of Vietnam-era jargon—but that was exactly what we needed to do. When I was a teenager, Soviet soldiers had made little effort to get to know us. Most people came to hate the Russians and ranks of Freedom Fighters swelled into hundreds of thousands of warriors, sworn to defeat these outsiders. It was the beginning of an epic Jihad for the Mujahedeen. I talked to the Marines about Jihad, and the Jihadist mentality.

“True believers want to die in a Holy War,” I explained. “If your enemy wants to become a martyr, he’ll do anything.”

“Don’t they believe that they’ll get twenty-two virgins in Paradise if they die for the cause?” asked Luffy-Lips.

“Seventy-two virgins,” I corrected him. “Seventy-two!”

“Wow,” he responded to laughter. “It’s hard enough finding even one around here!”

The India Marines listened to my lectures with discipline and respect. Platoons of around 40 Marines rotated through “school circles” for my classes in Afghanistan 101. Intensely interested in learning as much as they could about this remote and exotic land where they’d soon be risking their lives, they took copious notes and asked salient questions. I emphasized that one reason the Soviets hadn’t prevailed in Afghanistan was because they’d totally alienated the native population.

“The Russians didn’t make much of an effort to connect with local Afghans,” I explained. “I know that first-hand because instead of trying to befriend me, they stabbed me and shot at me when I got out of line in Kabul.” That really got the Marines’ attention.

“The Soviets relied on brute force,” I said. “They had incredible firepower and air supremacy. They could go where they wanted. But they totally pissed off the native Afghans, many of whom swore to fight to the death. And when Reagan gave the Mujahedeen some Stinger missiles, Soviet pilots were scared shitless. Check out the movie Charlie Wilson’s War. After the Soviets lost control of the air, and had millions of Afghans on a Jihad against them, they were beaten. They pulled out in disgrace in 1989. Two years later, the Soviet Union collapsed. Who’d have ever thought that the Afghan Mujahedeen would have helped to end the mighty Soviet empire?”

Using Soviet tactics could be fatal to many of us. No world power ever subjugated Afghanistan by force alone. Combining the judicious application of military might with smiles, patient interaction, and respect could help Americans prevail. We had to avoid provoking Jihad and that fast track to heaven for eager martyrs. Committed Communists had fought hard in the 1980s, but they didn’t believe in an afterlife and were never fanatical or eager to die. We needed to appreciate Afghan culture, which meant understanding Islam, area history, the role of elders, and the non-public status of women.

In Afghanistan a code called Pashtunwali guides many tribes. It’s a belief system that emphasizes honor—Nang. If an insult—Benanga—should occur, then Afghans are obliged to regain honor by any means. “Turning the other cheek” is an alien concept for those who follow Pashtunwali. Revenge or justice—Bada—must be exacted.

For example, the old zoo in Kabul had a famous lion. To show off, a man jumped in a cage with the lion to taunt the animal—who promptly killed him. The man’s brother returned to the zoo the next day with a grenade to kill the lion and avenge his brother’s death, even though his brother was an idiot and the lion just did what lions do. Revenge must still be exacted.

Pashtunwali accounts for tribal blood feuds that go back generations. If a tribe member is wounded or killed, then that member’s relatives swear eternal revenge. Pashtunwali beat the Soviets. When one Afghan was martyred, ten would swear revenge. What seemed a tactical success for the Russians only planted the seeds for more resistance, and every Afghan casualty created exponentially more Freedom Fighters.

The Americans—my Marines—could not make the same mistakes. Yes, we needed to deal with Taliban fanatics by any means necessary. And yes, that meant some family members would swear eternal revenge. Our challenge was to minimize casualties while engaging the population and winning their trust. If we did that, the Taliban could be isolated and eventually countered by the Afghans themselves. So we had a challenging dual mission requiring us to balance combat operations with civil affairs outreach.

The Marines had a history of working closely with indigenous forces. In Vietnam, USMC Combined Action Platoons (CAP) lived with native Vietnamese, won their trust, and eventually became effective partners. Typically, a Marine squad matched up with a Vietnamese platoon to establish a CAP. This approach was based on earlier models used by Marines in Haiti, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. The Marines also utilized a version of CAP to great effect in Iraq. This partnering needed to happen in Afghanistan as well but it wouldn’t happen without effective interpreters bridging the linguistic and cultural gaps. The success of the American mission depended heavily upon our terps. It was a major responsibility—difficult and dangerous. I took it all very seriously.

After several weeks of desert training, I’d gotten to know Marines from all the India platoons, as well as radio operators and Navy Corpsmen—usually referred to as docs. From staying close to the Boss, I picked up on some of the challenges he dealt with while running a company of over 200 men. Emergency leave was often required for everything from births to funerals. Some Marines occasionally needed to be disciplined, for which the Boss would hold office hours—non-judicial punishment short of a court-martial—to deal with transgressions. With my linguist’s ear, I noted that Marines pronounced certain English words differently. Various accents indicated that someone was from Boston, New York, Texas, or Minnesota. So not only did I listen intently to what each Marine said, I also listened to how they said it. I immersed myself in the Marine Corps culture and also tried to learn as much as I could from every individual Marine.

I had minimal contact with 3/4 Marines from the other four companies, although I’d try to compare notes with other terps when I got the chance. Sadly, I found out that Daoud left 3/4. He had a run-in with the first sergeant in his company and asked out of Twentynine Palms. I later heard he hooked up with the Army in Afghanistan.

I met some Marines from the battalion headquarters staff, people I’d get to know much better in Afghanistan, including the battalion executive officer, Major Dale Highberger—Darkside 6’s right hand man. The Battalion XO was another articulate, highly-educated officer with great interpersonal skills. He was especially smooth when dealing with visitors and civilians. He later gave me clearance into some headquarters areas and also encouraged me to write about my experiences. Maj Highberger emphasized how much the Marine Corps needed its interpreters which further reinforced my sense that accomplishing 3/4’s Afghan missions would largely depend on linguists like Mohammed and me.

Beyond the role-playing during tactical scenarios, I became well-drilled in Immediate Action procedures so I’d know what to do if we were attacked or ambushed. I hoped to get some weapons training and carry a rifle. I’d done that in front of a camera before, and I wanted to see what it would be like in the real world, but the policy was to keep the terps unarmed. I figured I’d talk the Boss into giving me a weapon once we got to Afghanistan. Intelligence officers brought us up-to-date on the local military and political situations in southern Afghanistan and how developments might affect our dealings with Afghans in our Area of Operations (AO). We also learned more about basic medical care and first aid—lessons I’d later use.

The Marines’ sense of purpose impressed me. They took everything seriously, giving attention to every detail. They asked me question after question about Afghanistan. Will there be dust storms? Will there be camels? Can we give candy to the kids? Some were easy to answer but others were harder—like the ones specific to recent developments and key personalities in our AO. The battalion intelligence people, the S-2 staff, tried to answer those questions. I reminded the Marines that I was from Kabul, that I’d never lived in southern Afghanistan, and that I’d also been out of the country for 26 years. In other words, a New Englander wasn’t automatically an expert on Texas.

Back from the field—in the rear with the gear—the Marines concentrated on embarkation, logistics, administration, and medical issues as our deployment date drew nearer. Admin people gave me a checklist of things I needed to do in order to deploy with the battalion, such as getting a valid will approved. Some Marines wrote letters to loved ones, to be opened in the event of their deaths. I thought about that, but was afraid it might be bad luck. I wrote no letter, but instead got a voice recorder to keep an audio diary—and for that possible book.

As our departure date approached I looked forward to leaving behind the training at Twentynine Palms to do the real thing in Afghanistan. I still felt no fear, only anticipation. I wondered when the fear would finally come—and what would prompt it.

One early September day, an India Company officer, Lieutenant Troy Gent, invited me to his house on base for dinner. The Gents lived in a modest grey and white two-story dwelling with a perfectly manicured yard that featured a big dog and two kids chasing each other around. Upon arriving, I immediately felt a welcoming, positive energy. Lt Gent was a Mormon from Utah, and one of the first things I noticed when we went inside was a framed picture of Jesus in the living room.

After dinner we talked about India Company, Afghanistan, living on base, and religion. I told Mrs. Gent that my wife shared her first name and that we had much in common, even though I was from Central Asia.

“So, are you a Muslim?” Amy Gent asked.

“I’m from an Islamic culture,” I explained. “My belief system was shaped by a Muslim influence early on. But as I’ve traveled around and met many different people, I’ve learned that all religions have something to offer and they all deserve respect.”

“Do you believe in Jesus?” Amy asked.

“I do,” I responded. “He’s in the Quran. And I also believe he’s coming back, somehow, someday. And believe it or not, I used to live in Utah myself. That’s where I became an American citizen.”

“Did you ever make it to the Tabernacle in Salt Lake City?” asked Lt Gent.

“Of course,” I replied. “What a beautiful place. I loved the music and architecture.”

The Mormons are so giving, going out of their way to help each other. Their volunteer actions like feeding the poor are more than just words. I pointed out similarities to Islam—a belief in prophets, a prohibition on alcohol, and so forth. “There’s common ground if you choose to look for it.”

The Gents were thoughtful and inquisitive, as well as generous. Their hospitality reminded me of the Afghan tradition of making guests feel welcome. I shared what I could about the spiritual aspects of Afghan life.

“Some people laugh at religious rituals and discipline,” I explained. “But strictly following rules can make people thoughtful and spiritual—like when Muslims fast during Ramadan. Catholics, Jews, Mormons and people from other religions use rituals that help them focus.”

The Gents were devout and didn’t even consume caffeine, much less alcohol. I sensed that their faith gave them structure, definition, and hope, which moved and impressed me. Their serene home reminded me of a chapel, a place of respect.

Our nice evening had an undercurrent of apprehension. In October, the 3/4 Marines would head off to Afghanistan for seven months. We knew that we were going to a dangerous place in a dangerous country, where many other Marines had been killed or maimed. In some ways it’s harder for the loved ones left behind, who can only wonder, worry, and pray. My own Amy visited Twentynine Palms several times and the uncertainty took a toll on her as well.

Before I left the lieutenant’s house, Amy Gent took me aside. “We’re really depending on you, Fahim,” she said. “You know the languages. You know Afghanistan. You know what to look for. Please keep my husband safe.”

“I promise,” I told her.

As I drove away from the Gents’ place I turned around and looked back. My evening at their loving home had been more than a social event. It also had a powerful spiritual component. My personal beliefs combine elements of several religions. I know there are powers in the spiritual realm that guide and protect life on earth, according to an unknowable plan. I sensed the presence of angels at that house. Lt Gent and his fellow Marines from 3/4 were risking their lives to give my native land a chance at a better future—and the importance of my role had just been underscored by the lieutenant’s wife.

I’d often considered my homeland to be cursed. In my darkest hours, I doubted Afghanistan could overcome the profound challenges of being a war-torn, divided land—among the poorest countries on earth. If there were to be any hope for such a backward, impoverished nation, it lay with the Americans now committed there. I’d seen first-hand how hard the Marines trained and I felt a new sense of hope—and responsibility. I thought of my daughter Sophia, and how I’d feel if I had to entrust her safety to someone else. Then I really understood Amy Gent’s poignant plea.

We had to trust in God, but I had to trust my own linguistic and acting skills as well. Precious lives were at stake. I felt sober and focused.

As the deployment date drew near, the Marines spent extra time with their families. I wanted my parents to meet our 3/4 Marines. My mother liked that the U.S. sought to make Afghanistan a better place. She was proud of me and I appreciated her support—support that hadn’t always been there. Earlier, she and my father had made it clear that they didn’t want me to go back to Afghanistan. Yes, they worried about me getting hurt or killed, but it was more than that, especially with my father, who thought some in the Afghan community would consider me a traitor. Some Afghans were reflexively anti-American, even after the U.S. had invested so much blood and treasure in Afghanistan. Did these Afghan expatriates want the Taliban to return to power in Kabul?

Afghans in America occupy a broad philosophical spectrum. Many, like me, assimilate and develop a love for their adopted country. Others choose to remain segregated in various cultural enclaves and hang on to the old customs, traditions, and language. Those who don’t assimilate continue to identify with elements from the old country—sometimes even the Taliban. I know many of them hated me, and some of them were close to my father, who wasn’t much of an assimilator himself.

American Marines wanted to help Afghanistan, not conquer or exploit it. I thought that if my parents visited Twentynine Palms they’d understand things better. So in late September I went over and picked them up in Orange County. As we drove back east on I-10, I explained as much about the Marines as I could, emphasizing their professionalism and proficiency. When we got to the base, the sentry checked my credentials and waved us in with a flourish. My parents nodded to each other, recognizing the respect I’d been given.

We parked the car and walked around. I showed my parents the Base Exchange, library, theater, and finally the 3/4 and India Company areas. My mother talked to some of the troops, who were always polite, confident, and reassuring. She kept saying, “I’m from Afghanistan. Thank you! Thank you!” to every Marine she met.

The Marines appreciated her sentiments. They smiled and replied with various versions of “Thank you ma’am. Happy to help. That’s our job. We’ll kick their butts.”

Even my father softened a little, but he remained conflicted. I wondered if perhaps he and I might get to a better place in our relationship after I returned from the deployment—if I returned. Still, while driving my parents back to Orange County, I decided that their visit to the Marine base definitely brought us closer together.

“What wonderful young men you work with, Fahim,” my mother gushed.

“Yes,” I replied. “They’re impressive professionals. Don’t you think so, Dad?”

“Maybe,” said my father.

“They said they can’t wait to get the Taliban,” my mother added.

“They are so motivated,” I said. “Aren’t you pleased that I’m working with such people?”

“Maybe,” said my father.

With 3/4 back in garrison making final deployment preparations, Capt Benson hosted a barbeque at his off-base residence. He wanted families to mingle and get to know the India Company leadership better. Our team was really coming together.

Amy couldn’t make it, so I ended up as one the few there without a wife. Mohammed also arrived stag. I got there early with a 12-pack of Corona for Capt Benson and then I put my culinary skills to good use by helping the Boss’s wife, Susan, cut vegetables.

The Bensons had a dog named Gunny, who jumped all over me in the kitchen. When Mohammed walked into the kitchen a few minutes later, Gunny immediately growled at him. Mrs. Benson noticed.

“Susan told me that Gunny liked you,” the Boss told me later. “She said she trusts you but not Mohammed, because Gunny doesn’t like Mohammed.”

“Just call me ‘Dog’s Best Friend,’” I replied with a smile.

When we were all outside after eating, Mrs. Benson tried to get the dog back in the house. She yelled from the doorway, “Gunny! Get in here right now!”

“Yes, ma’am,” replied GySgt Romero, the real Company Gunny. Everyone laughed—even Mohammed.

Then the Boss spoke and—among other things—said that the presence of trained interpreters like Mohammed and me gave him great confidence that India Company would succeed in Afghanistan.

The day after the barbeque, SSgt Cooke saw me in the company area. “Fahim, can we talk?”

“Sure,” I said. “What’s up?”

“Mohammed says he may not deploy,” explained Cooke. “But he wouldn’t elaborate. Are you OK? What’s going on?”

“I’m good to go,” I said. “I’ll try to see what’s happening.”

I found out that some linguists were afraid. They’d learned that 3/4 was headed to northern Helmand Province—one of the most dangerous places in the country. Marine battalions that deployed there earlier suffered terrible casualties, mostly due to IEDs. Besides those who’d been killed, there were many single, double, triple and even quadruple amputees. 3/4 would be responsible for a vast and hostile area.

Our battalion would replace 2/3, the latest in a string of Marine battalions seeking to establish a presence in a region long-dominated by the Taliban. Before the Marines arrived, British troops—including Prince Harry—had fought for years throughout that AO. The Brits and then the Marines suffered heavy casualties and remained over-extended. Coalition forces were spread so thin that the Taliban still controlled most of the area. Our AO included northern Helmand Province as well as parts of Nimroz and Farah Provinces, where the great Hindu Kush Mountains abruptly rose from the flat desert floor. We’d eventually establish a headquarters in the crossroads town of Delaram, where the three provinces converged. It was also only a short distance to Kandahar Province—the birthplace of the Taliban.

The Taliban flourished in greater Helmand Province, since the Helmand River Valley is the center of the world’s greatest poppy fields. Poppy farming and opium and heroin production powered the local economy and provided considerable revenue for the Taliban. They’d fight hard to protect their drug enterprise. While most of the people were not members of the Taliban, they distrusted foreigners who might threaten their way of life. Soviet forays into the area 25 years earlier had been disastrous.

The locals also distrusted the central Afghan government. In fact, they hated anything associated with Kabul. District governors or sub-governors were constant assassination targets, and the government officials who survived were thought to be compromised by the Taliban.

Before the Taliban re-emerged in the years following their 2001 overthrow in Kabul, corrupt local police had completely alienated the Helmand population. Official corruption was so bad that nothing happened without bribes. Eventually, the corruption was so bad that people tolerated the Taliban as a less crooked alternative that could bring some stability—but at the terrible cost of what little freedom the people still enjoyed.

When I was young, Afghanistan’s many tribes had co-existed with little conflict, but after 1978, the Communists successfully created tribal jealousies to divide the people. The Taliban similarly exploited these rivalries.

Major tribal groups in Afghanistan included the Baluchi, Hazara, Nuristani, Pamiri, Pashtun, Tajik, Turkmen, and Uzbek. Almost all were Sunni Muslims, except for the Shiite Hazara. In northern Helmand, the Durani—a Pashtun tribe—predominated. Sub-tribes like the Barikzoy, the Nourazai, and the Popalzai were often at odds. These tribes fought over precise boundaries between tribal village areas, or about who controlled certain roadways and distribution routes. At one time, elders resolved these problems, but now the Taliban exacerbated these tribal divisions, knowing that subsequent violence could create a cycle of conflict and chaos they could exploit.

In the eastern part of the AO—around Now Zad—the Taliban dug in so deeply that they actually created World War I-style bunkers and trenches behind vast minefields. The continued existence of this pervasive defensive complex was a defiant representation of Taliban power. It seemed to invite attack by signaling that the Marines were too weak to assault or liberate Now Zad and displace the Taliban. The 3/4 Marines would have the mission to take down this symbol of Taliban dominance when they arrived in-country. Now Zad meant a huge fight.

Rumors of this future showdown filtered down to the terps, who knew that Darkside 6 and 3/4 faced a daunting AO. Although the Marines looked forward to the challenge, some linguists thought our mission there to be not only dangerous, but hopeless, and they expressed grave doubts about surviving in Helmand Province. Finally, all the terps got together to talk in a Best Western hotel room just days before our deployment. Most were afraid and wanted to quit and turn in their gear.

“Daoud left and got a better job with the Army,” said Abdullah, one of the youngest terps. “I don’t want to live in a hole over there in Helmand and help find IEDs. I have a life to live. I heard we can all get reassigned to Army jobs in Kabul if we request that.”

I looked around the room and sensed most of the terps felt the same way.

“I don’t know about any of you, but I’m going forward,” I said. “I want to pay my dues to America. And when I come back, I’ll be able to sleep well and live with myself.”

The fat terp named Said looked at me with a pained expression. “Fahim!” he exclaimed. “Don’t you know what they expect us to do over there? They want us out on patrols! We don’t need that. You’re a Hollywood actor. You have a family. A home. Money. A future. Are you crazy? Why do you want to go get blown up in Helmand?”

I knew we could make a difference over there. How could we break faith with these Marines—and their families—who so depended on us? I thought of Amy Gent.

“I’m going with the Marines,” I said. “I’ve been here for 24 years and I’m an American. I owe this country.”

“Then you’re a fool!” exclaimed Said.

Some of the terps were Afghans who’d just come to America with green cards. They’d stayed with the Mission Essential Personnel program long enough to collect a $10,000 bonus. Now they wanted out.

“Yes, you’ve been safe in America for 24 years,” Mohammed shot back. “You have no idea what it’s like now in Afghanistan. You don’t understand what the Taliban have done to our country.”

“That’s OK,” I replied. “I’ll go back and see with my own eyes. It’s wrong for you to take the money and walk away. It’s stealing. The Marines need us. I’m going to pay my dues to my country.”

The situation was a microcosm of what we’d face in Afghanistan. The terps with the green cards were products of a culture of corruption. They were survivors from a land that had been at war for 30 years. They were cold and calculating, with no loyalty to America or the Karzai regime. They were pragmatists who understood the complexities of life in Afghanistan. Things were not black and white for them—only various shades of grey. I recalled a couple of them laughing at a Marine who’d been hurt training in the desert.

After the meeting ended, I wondered how many terps would pack up and leave.

On October 6, seven of our 11 remaining translators quit, leaving 3/4 with only four interpreters.

On October 9, our battalion finally boarded airplanes and took off from the Twentynine Palms airstrip, beginning a 10,000 mile journey that would take 3/4 to Germany and then to Manas Air Force Base in the former Soviet Republic of Kyrgyzstan. After a couple days at Manas, we got on military transport planes for a long flight to Bagram—an American air base north of Kabul that had once been the main Soviet air facility during the 1980s.

We donned helmets and flak jackets and put in our ear plugs. As we strapped ourselves into the transport, I looked at the Marines around me. They were poised and confident. I didn’t sense a bit of fear. Five hours later, we landed at Bagram—almost a mile above sea level. My pulse quickened as I unbuckled my seat belt and stood to file out of the plane. Moments later, I set foot on the tarmac and looked around. A cool breeze blew as I scanned the great mountains. After an absence of 25 years, I’d finally returned to my native country.

It was a sunny October afternoon. The air facility had three big hangars, a control tower, many support buildings, and even some oversized tents. The mountains were green and snow-free. Old Soviet planes and tanks were still visible around the base periphery—relics of the disastrous war of the 1980s. Even though Bagram was only an hour’s drive from Kabul, I’d never visited the place as a youngster. I felt no desire to return to Kabul, despite my proximity. The place conjured up too many bad memories.

We watched aircraft taxi while Marines unloaded wooden pallets with our sea bags from the transport. I scanned the towering peaks where the enemy lurked—along with invisible mines and IEDs. We retrieved our sea bags and gear, got into single file, and moved to assigned billeting space in a large tent where we’d await further transport to Camp Leatherneck.

I felt good—ready to go to work. I chatted up the Marines on either side of my space and then lay on my cot and reviewed some notes. I thought of Germany and Japan. The Americans fought and defeated both countries during World War II but maintained a presence in each nation until both were rebuilt. Now they were both prosperous American allies. Could a similar scenario play out in Afghanistan?

I stowed my paperwork under my cot after most of the lights went out. Before closing my eyes, I regarded the prone Marines racked out on the many military-issue cots squeezed into the big tent. I wondered which ones would not return home with us. Then I closed my eyes and fell asleep in my native land for the first time since 1983.