It was an enclave, insular and, in a city known for brewing and bratwurst, predominantly Irish; a company town in some respects, working-class but by no means poor. The Catholic parish, St. Rose of Lima, counted nineteen millionaires, including the Millers of brewing fame, among its congregants, and its charismatic pastor, Father Patrick H. Durnin, was one of the city’s best-connected and most effective fund-raisers. Along West Clybourn Street were dentists, barbers, a cobbler, a druggist, four grocery stores, a plumber, hardware, and a men’s shop. The names on the businesses spoke for themselves: Corrigan, Curley, O’Leary.

Merrill Park didn’t start out that way. The original plat fell south of the estates along Grand Avenue at the west end of Milwaukee. Sherburn S. Merrill, general manager of the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad, built his Victorian mansion on Grand at Thirty-third Street, then gathered up the land along three sides, from Thirtieth to Thirty-fifth Streets and back to the edge of the Menomonee Valley. Merrill’s company, meanwhile, acquired nearly half a square mile of marshland in the valley itself, and in 1879 began work on the Shops of West Milwaukee, where the rolling stock of the state’s largest railroad would be manufactured and maintained.

By 1900 the railroad was the city’s largest employer, and many of the men who worked there—blacksmiths, woodworkers, painters, machinists—found a vibrant neighborhood of cottages, single-family frame houses, and spacious duplexes just up the steps in Merrill Park. Mostly they were Germans and Poles, first- and second-generation Americans who brought their skills with them from Europe. The Irish influx started in 1892, after a disastrous fire in the Third Ward left many of them homeless. The Irish were the men on the trains—the engineers, firemen, brakemen, switchmen—and soon they came to dominate. Merrill Park wasn’t entirely Irish, but by the turn of the century it sure seemed that way.

So it was to Merrill Park that John Tracy naturally came in 1899, installing his young family on the first floor of a modest duplex at 3003 St. Paul Avenue, just a block from the Clybourn business district and two from St. Rose’s. Like a lot of other people in the neighborhood, he worked for the St. Paul, but he wasn’t in the shops nor on the trains either. Rather, he clerked in offices contained in a nondescript brick building around the corner from Union Depot, where he could gaze out the window at almost any hour of the day or night and watch freight and passenger stock roll gracefully across Second Street, arcing to the west toward Fourth. It was a factory district, the heart of the original village, where boots and soap and stoves got made, and where ironworks and hardware companies sat alongside packing plants and warehouses.

John Edward Tracy was born into railroading. His father, John D. Tracy, emigrated from Galway during the Great Famine and went to work for the Vermont Central at the age of fifteen. In 1854 he moved to Wisconsin and joined the Milwaukee & St. Paul as a section foreman. He made roadmaster in Savanna, Illinois, then settled in Freeport, in 1870, where he was in charge of the track to Rock Island. He had four sons, three of whom worked for the line. John, born in 1873, had a head for numbers and became a bookkeeper. His brother Andrew, born in 1883, held a similar position with the Illinois Central.

The Tracys were unusually prominent for a railroad family. J.D. was treasurer of the building committee for St. Mary’s Catholic Church, which anchored a section of town that became known as Piety Hill. He contributed a pillared altar of marble and onyx, and for years was one of the directors of St. Mary’s School. He was also one of the organizers of the State Bank of Freeport, and one of its directors from the very beginning. It could be said the Tracys lived on the right side of the tracks, if only just barely. Liberty Division abutted the easements, which ran roughly parallel to the Pecatonica River. John D. Tracy shared a four-bedroom wood frame house with his wife Mary, their daughter Jenny, and their sons John, William, and Andrew. Two daughters by his first wife, Letitia, became nuns, and a son, Frank, a journalist and newspaper editor. Letitia died in childbirth in 1865, and John wed Mary Guhin, from County Kerry, the following year.

John D. Tracy was honest, industrious, charitable, a pillar of the community, but the Tracys were still lace curtain Irish, devoutly Catholic in a town that was largely Methodist and Presbyterian. Freeport was known for its Henney Buggies, its Stover windmills and bicycles, and the coffee mills and cast iron toys manufactured by Arcade. Rail service was the landbound city’s lifeline, but when John Tracy, the younger, began courting the twenty-year-old daughter of Edward S. Brown, son of the late Caleb Wescott Brown of the Browns of Rhode Island, John’s upright father couldn’t begin to pass muster with the merchant miller of Stephenson County.

According to family lore, Caleb Brown was directly descended from the famous mercantile family of Providence, specifically Nicholas Brown, who entered the family business at an early age and whose son was the Brown after whom Brown University was named. Caleb Brown came to Freeport by way of Buffalo, Oneco, Cedarville, and Silver Creek. In 1857 he built a flouring mill on the banks of the Pecatonica, which, starting in 1865, supplied a grain-and-feed store he opened on Galena Avenue. He bought the Prentice house, a ponderous brick showplace on West Stephenson Street, and joined the First Methodist Church. Gradually, the operation of both Brown’s Mill and the store fell to his eldest son, Ed, a Civil War veteran who was also town supervisor and a member of the First Presbyterian Church. Ed Brown married Abigail Stebbins of Silver Creek in 1867, and the couple had three children who lived to adulthood: Emma, Caroline, and Frank.

Exactly how John Tracy made the acquaintance of Carrie Brown is unknown, but it is unlikely that they met socially. John attended school at St. Mary’s and the University of Notre Dame, while Carrie graduated from Freeport High and spent only a short time in college. It may be that they met through the family business, or perhaps at the bank, where John had been a teller. She was one of the most beautiful girls in Freeport, a “down easterner” who didn’t lack for proper suitors. When word got around she was seeing an Irish Catholic from Liberty Street, the town was properly scandalized. Ed Brown, in fact, may well have had a word with Tracy Sr. on the matter, for J.D. imposed a strict curfew on his two eldest boys.

“This door will be locked at ten o’clock,” he declared, “and nobody will be allowed in after ten o’clock!” Both John and Will appealed to their sister Jenny for help. “I would sit up on the stairs or at the upstairs window and wait for those two to come home,” Jenny later told her daughter Jane. “I would sneak down and open the door so that they would be able to come in the house, and God knows sometimes it was two or three o’clock in the morning and I would have sat there all night. My nerves were ruined when I was a very young girl.”

There was little love lost between the Tracy boys and their rigid old man, but Jenny adored her father and faithfully went to Benediction with him every Sunday night. J.D. wasn’t any happier about his son’s relationship with a Protestant girl than were Ed Brown and his family, but John and Carrie were the real thing, a genuine love match at a time when arranged marriages were still common among the Irish. Amid much gnashing of teeth, the union was made legal on the evening of August 29, 1894. The Browns opened their home on upper Stephenson for the event, and Father W. A. Horan of St. Mary’s agreed to officiate. “In accordance with the wishes of the bride and groom the wedding was a very quiet and informal affair,” the Daily Journal reported, “no attempt at display being made excepting that the parlors were very prettily decorated for the occasion.” Only a week earlier, the groom had traveled to LaSalle to accept the position of assistant cashier with a new bank, and so after the formalities of “a bountiful feast” had played themselves out, the newlyweds left town, putting a good one hundred miles between them and Freeport and their painfully incompatible families.

It was in LaSalle that Carrie Tracy first sensed the physical intolerance her husband displayed toward alcohol, a characteristic passed to both John and his brother Will through the Guhin line of the family. Carrie herself never drank and her husband rarely did so at home, but when he did the results were immediate and profound. There is no evidence that John Tracy was a mean or even a disagreeable drunk. Drink, in fact, may well have brought out his genial side, but he was prone to disappear, leaving Carrie at home alone, sometimes for days, with no word as to where he was. Without the sobering influence of his father at hand, John developed a reputation at the bank as being unreliable. Then there was a whispered story within the family that he had been caught with his hand in the till. Within a year they were back in Freeport, where John’s father had gotten his son his first job out of college as a teller at the State Bank, and where he now settled him as a bookkeeper with the St. Paul.

The home of John D. Tracy and family, Freeport, Illinois. (SUSIE TRACY)

Living in the same house with John and Mary and Jenny and Will and Andrew was trying for the two of them—especially Carrie, who was used to grander things—and the close quarters got downright stifling with the birth of a ten-pound boy on the morning of June 15, 1896. The baby was baptized Carroll Edward Tracy, with his aunt and uncle serving as godparents. Shortly thereafter, John and Carrie moved in with the Browns, where there was considerably more room and staff, but where the atmosphere was no less strained or uncomfortable. On the whole, it was a better arrangement than before, but the Browns were a starchy bunch, sociable but distant, and John’s occasional binges didn’t endear him to his in-laws. When a job opening presented itself in Milwaukee, John Tracy pursued it with all the charm and resolve he could muster, and when the time came to again say goodbye to Freeport, the relief all around was palpable.

It wasn’t long after the Tracys’ arrival in Milwaukee that Carrie learned she was once again with child. Merrill Park was a vast improvement over Freeport, a modern neighborhood with conveniences and open space and plenty of kids. It was just far enough from the center of town to offer a pleasurable blend of urban and rural living. There were no saloons or livery stables, Sherburn Merrill having thoughtfully placed deed restrictions on such enterprises (as well as any other businesses “detrimental to the interests of a first class residence neighborhood”). The city center was just minutes away, yet one could stroll due east a block and gaze down into the Menomonee Valley, four miles long and a half mile wide, and see virtually every kind of industrial operation, from breweries to grain elevators to tanneries, stockyards, and flour mills. Carrie’s pregnancy took her through a relatively mild winter, and although she was hoping for a girl, the result delivered by Dr. O’Malley on Thursday, April 5, 1900, was another boy. Carrie made no effort to hide her disappointment, and found it impossible to come up with a name for the child.

As the unmarried girl in the family, it fell to Jenny Tracy to ensure the baby got baptized, and it was on Sunday, April 22, that she and her brother prepared to take the seventeen-day-old boy to St. Rose’s for the sacrament.

“What are we going to name him?” she asked Carrie.

“I’m so disappointed that he’s a boy,” Carrie moaned. “He was supposed to be ‘Daisy’ after my good friend Daisy Spencer.”1

“Why don’t you call him Spencer and honor Daisy that way?”

“Well …” said Carrie in a dispirited tone, “that’ll be all right.”

Jenny was so relieved to have a name for the baby that the matter of a baptismal name didn’t occur to her until she and her brother were already on their way to Mass. “John,” she said, “you know that this child has got to have a saint’s name. We can’t present him without a saint’s name. What do you want to call him?”

“I don’t know,” said John. “What do you think?”

“Why don’t we honor Bonnie?” Catherine Tracy, the younger daughter of John and Letitia Tracy, had become Bonaventure, Mother General of the Sinsinawa Dominicans.

John smiled and nodded his agreement. “That’s all right with me,” he said.

When they brought the baby, swaddled in white, up to the font, Father Durnin said, “What is the name?”

Jenny said, “Spencer Bonaventure.”

And the priest asked, “Boy or girl?”

When Carrie Tracy learned her new son had been given “Bonaventure” as a middle name, she was unhappy, as much for the baby’s sake as her own. (She may have learned that Bonaventure was the patron saint of those afflicted with bowel disorders.) When the certificate of birth was filed on June 4, 1900, the boy’s name was given as “Spencer Bernard Tracy” and it remained that way for the rest of his mother’s life.

The only industrial enterprise to rival the West Milwaukee Shops in terms of size and employment was a rolling mill that occupied nearly thirty acres at the southeastern corner of the city where the Kinnickinnic River flowed into Lake Michigan. As the shops had given birth to Merrill Park, the iron and steel mill founded in 1867 by the Milwaukee Iron Company begat the similarly self-contained village of Bay View.

Initially, the neighborhood was populated with iron and steel workers imported from Great Britain, but as factories sprang up to the west of the mill complex and the need for support services grew, the ethnic makeup of the area became considerably more diverse. By the time John Tracy moved his family to Bay View in 1903, there were Irish mill hands, a sizable Italian colony, and significant numbers of Poles and Germans. The architecture was a pleasing mix of Queen Anne, Italianate, and Greek Revival, with a few Civil War–era farmhouses remaining. New single-family frame houses were built alongside duplexes, and the dense woods on the lakeshore were only a short walk from the compact business district along Kinnickinnic Avenue.

The mill itself employed 1,600 men, transforming ore from Dodge County and the Lake Superior region into steel and iron bars, tracks, billets, rails, and the square-cut nails that held much of Bay View together. Then there were the companies that sprang up around the mill, producing products for the building and transportation industries.

One such enterprise was the Milwaukee Corrugating Company, which took its first orders for galvanized roofing shingles in 1902. Over time, the line expanded to include pressed-tin ceilings, wall tiles, skylights, and ventilators for barns and creameries. Milwaukee Corrugating was a prosperous, growing concern when John Tracy joined the company. Exactly why he left the St. Paul isn’t clear, but his promotion to general foreman in late 1901 would likely have put him in closer proximity to the numerous saloons that served the men of the shops, and a stop on the way home would not only have led to calamity but a clash with the abstentious culture so carefully shaped by Sherburn Merrill. In little more than a year, John was out at the railroad and glad to land yet another clerk’s position in the factory district north of Lincoln Avenue.

The move to Bay View coincided with Carroll Tracy’s start in school and Spencer’s emergence as a hyperactive terror. Not long after the family’s relocation to a roomy duplex on Bishop Avenue, the younger boy took a firm grip on a cast iron fire engine and brained his older brother with it. He watched calmly as his mother ministered to the screaming seven-year-old, then settled into a soothing and sympathetic chant: “Poor Ca’l, poor Ca’l …” Carroll Tracy was a good son, his mother’s favorite, but Spencer was something else again, and his aunt Emma predicted John and Carrie would have their hands full with the boy she ominously referred to as “that one.” Said Emma, “He’s a throwback. I dare say he is part Indian.”

Bay View was full of young working-class families. Rowdy kids were everywhere, yet Spencer stood out. In an early picture he radiates energy, his deep-set eyes suggesting not so much a thoughtful, well-behaved child as a malevolent raccoon. “He was in dresses when I first saw him,” said Mrs. Henry Disch, an early neighbor. “He was bubbling with life. I don’t believe he ever sat still. I can’t remember him sitting down in a chair or reading a book. His brother Carroll was a quiet boy. He liked to stay inside and listen to the talk of his elders, but Spence was always outside with the boys.” When the kids were cleaned up and brought to dinner, Spencer sat restlessly as the adults talked, kicking the legs of the chairs on either side of him and methodically peeling the enamel dots off Mrs. Disch’s new salt and pepper shakers.

It was in Bay View that Spencer’s spiritual development began with his weekly attendance at Mass, his mother remaining at home while his father walked the boys to Immaculate Conception, the Catholic parish that served the neighborhood. The sacred rite was a pageant of spectacle and wonder to an impressionable three-year-old—the singing, praying, kneeling, the nourishment of the Divine Liturgy and Holy Communion. However close he was to his indulgent mother, Spencer grew closer still to his father in those early years, the shared experience of worship a powerful bond that would hold firm in the years to come. It became Carroll’s job to corral his kid brother like a gentle sheepdog, hovering over him before and after while greetings were exchanged between their father and the neighbors on the steps in front of the church. And when it came time to put Spencer in kindergarten in 1906, it too became Carroll’s job to lead him the eight blocks to District 17 School #2 on Trowbridge Street.

School widened Spencer’s social circle and encouraged a tendency to disappear. “I began to show signs of wanderlust at seven,” he later admitted. “I wandered completely out of the neighborhood and struck up an acquaintance with two delightful companions—‘Mousie’ and ‘Rattie.’ Their father owned a saloon in a very hard-boiled neighborhood. It was a lot more fun playing with them than it was going to school.” Mousie and Rattie were nine and eleven, respectively, and incorrigible truants. “Being sentimentally Irish,” Spencer said, “that common-enough episode in a kid’s life was to have a lasting effect on my future. For the first time I saw my mother cry over me. I resolved in an immature way never to make her cry again. I don’t mean to intimate that I became a model boy. I didn’t.”

The family’s pattern of movements during these years suggests they were as much a result of Spencer’s abysmal attendance record as they were for reasons of economics. In 1907 the Tracys moved closer to the school, cutting three blocks off the daily commute. In their next relocation, the family settled within sight of the building, where the route home was a short walk through a brick-paved alley. Just beyond the schoolyard was dairy pasture, forest, and, at a gravel road called Oklahoma Avenue, the Milwaukee city limits.

Spence seemed to prefer the rougher neighborhoods to Bay View proper, and frequently he would return home with a band of scruffy-looking kids who seemed as if they hadn’t eaten in a week. Invariably Mrs. Tracy would fix sandwiches—cheese on buttered bread—only to discover that Spencer had sent one or more of them home with clothes from his own closet. “I can honestly say that back of every one of Spencer’s exploits was something fine like sympathy, generosity, affection, pride, or ambition,” she said in 1937. “There was not a mean bone or thought in him. True, he broke windows with the same alarming and expensive regularity boys do today. And he would get embroiled in fights to help a friend—fights, incidentally, from which Carroll invariably would have to rescue him because he was so thin and sickly a child until he was 14 that he could never finish on his own what he was quick to start or join in … Even though it meant added work for me and bigger bills for John to pay at the stores, neither of us could find it in our hearts to punish or discourage him from such a fine philosophy.”

The Tracy family, Bay View, circa 1908. (SUSIE TRACY)

With its hundreds of mill and factory workers, there was no shortage of saloons in Bay View, many of which, called “tied houses,” were exclusive (or “tied”) to the output of a particular brewery. The Globe Tavern on St. Clair Street was built of the same Cream City brick as the Romanesque school on Trowbridge, and it proudly displayed the belted globe of the Schlitz Brewing Company atop its turreted entryway. Vollmer’s Grocery Store and Saloon was due west of the Globe on Lenox. Kneisler’s White House Tavern stood boldly at the corner of Ellen and Kinnickinnic Avenue, and yet another Schlitz tavern was under construction just outside the walls of the rolling mill on South Superior. The walk to and, especially, from work became an obstacle course of temptations for a man of John Tracy’s cravings, and he didn’t always negotiate the route with complete success. An eminently convivial man, John honored the Irish tradition of the saloon as a center of the community, and he often found it impossible to pass one without stopping to pay his respects. At other times he walked a tortured path that purposely avoided all licensed establishments, a not altogether easy task, in that saloons, like stores and churches, were part of the fabric of a residential neighborhood and stood side by side with new homes, parks, and schools.

Despite the daily challenges he faced, John Tracy won favor with Louis Kuehn, the president of Milwaukee Corrugating, and found himself promoted to traffic manager within the space of a year. Even so, he would, on occasion, fall spectacularly off the wagon and disappear without a trace. The boys had no clear understanding of what was happening; their father worked long hours and it was only their mother’s tears that told them something was dreadfully wrong. Carroll did what he could to comfort their mother, but Spencer withdrew, possibly wondering, as the children of alcoholics often do, if his father had gone off because of something his younger boy had said or done.

What they couldn’t have known was that alcoholism ran in their grandmother’s side of the family, and that their Uncle Will Tracy was even more severely afflicted with “the creature” than was their own father. It was never discussed, a matter of unspoken shame, a sin against wife and family, a good man’s weakness. At times like these there was little Carrie could do, and a call would go out to Andrew Tracy, John’s genuinely abstentious brother, who would come to Milwaukee, find his elder sibling, clean him up, and bring him back. The process took its toll on John, whose genial nature hid a prematurely lined face and whose hair, in his mid-thirties, was already beginning to gray at the temples. It took a toll on his brother as well, for there was genuine terror in the fact that Guhin blood also ran through Andrew Tracy’s veins. “Uncle Andrew was paralyzed, afraid, of liquor,” said his niece, Jane Feely. “He just wouldn’t touch it. Not because he wouldn’t want it, but because he was so terribly afraid of it.”

Summers for the boys were spent in Freeport, where they divided their time between the Tracy house in Liberty Division and the Brown house on upper Stephenson. Grandfather Brown’s asthma was bad, aggravated by the summer dust, and the shades were always pulled. It was dark and hot inside, all stiff and lifeless with a horsehair sofa in the sitting room and a five-octave square piano that nobody ever played. Spencer escaped whenever he could—to the circus, to the moving pictures, to the Stebbins house on Walnut Street. Warren Stebbins was the younger brother of Abbie Brown, but the family never looked forward to Spencer’s visits. “He was terrible,” said Warren’s granddaughter, Bertha Calhoun. “He was just into everything.” Bertha’s father, Clarence Forry, once described him, without affection, as “one big ugly freckle.”

When there weren’t any horse races or baseball games at Taylor’s Park, and no kids were swimming in the river, the storefront theaters along Stephenson Street offered the best respite from the heat. The Majestic was a favorite hangout when Spencer could cadge a nickel, as was the Superba across the street. When there wasn’t money he would stand and stare at the displays out on the sidewalk, sighing extravagantly, or fix the box office with a woeful gaze until the woman at the window, a friend of his Aunt Mame’s, would say, “Oh, Spencer, go on in!” His Aunt Emma once refused him the money to see a movie about Jesse James. “You’ve got enough wild ideas without going to see those things.” He thought hard a moment, then announced The Life of Christ was playing at the other theater. “You wouldn’t want to keep me from seeing that, would you?” He got the nickel, but Emma Brown had little doubt as to which film he saw.

John Tracy sent a dollar a week to be split between the boys. What Carroll did with his share was a mystery, but Spencer, noting the economic divide between the Tracy and Brown households, always seemed to be broke. “At that time you could buy a bag full of candy for ten cents,” said Frank Tracy, the son of Andrew and Mary Tracy. “My mother said that very often, Spence would come home with a loaf of bread and give it to his grandma. ‘That’s for us.’ Probably eight or nine cents a loaf at that time. Another time he was helping Grandma Tracy in the kitchen, and she had a paring knife and it was dull, wasn’t working right. So the next time he got his fifty cents, he went over to Woolworth’s and he bought a paring knife for his grandmother. My mother was telling me this and she said, ‘He was always very generous.’ He did other little things like that around the house, things Carroll would never think of doing.”

Spencer hated the tradition of the Saturday night bath, and the task of getting him to take one fell to his Aunt Mary. “She’d try to round him up and get him in the tub,” Frank said. “Spencer was always pretty hard to find. She’d literally have to push him to the bathroom, and then she wouldn’t hear anything. She’d ask Spencer, ‘Are you taking a bath in there?’ He’d say yes, but he’d be sitting on the floor fully clothed—even his hat still on his head—splashing the water with his hands.” Even when he actually got into the tub, he wouldn’t shampoo his hair, and his grandmother would invariably say, “Your hair stinks!” Finally, it was decided the boys would do better under the no-nonsense supervision of Grandmother Brown, and Spencer wore a collection of scapular medals for the occasion.

“What are all these things?” she demanded, yanking at them.

“Don’t take ’em off my neck!” he exclaimed. “You can’t take those off! They’re holy!” Her expression must have told him she thought he was crazy, for he took them out and started to explain: “Well, this is so you won’t get drowned … and this is so you won’t get killed … and this one is so you won’t commit a sin …”

“You certainly won’t drown in that bathtub!”

Thoroughly scrubbed, his hair washed and teeth brushed, Spencer and his brother would be returned to Grandma Tracy so that they could serve Mass at St. Mary’s the next morning. With her husband dead and her daughter Jenny now married, Mary Guhin Tracy sought the solace of the bottle (“a drop o’ th’ cratur”), and her son-in-law’s gift to her each Christmas was a case of beer and a jug of good Irish whiskey. “She would always specify that it be delivered after dark,” her granddaughter Jane remembered, “so the neighbors wouldn’t see.”

“From the time Spencer was a tiny lad,” recalled Carrie Tracy, “Carroll appointed himself as special guardian. He worried more about Spencer than the rest of the family put together.” Carroll had an almost pathological fixation on his brother, as if hovering over him and getting him out of scrapes was in some way compensation for their father’s absences. He had the example of Andrew Tracy and his palliative visits to Milwaukee when times got bleak, the sober brother who could always be relied upon in times of distress. Try as he might, Carroll’s dogged oversight was never much of a substitute for a father’s attention, and the family’s proximity to the Trowbridge Street campus did little to improve the boy’s performance. “I never would have gone back to school,” Spencer once said, “if there had been any other way of learning to read the subtitles in the movies.”

He discovered the Comique, a storefront theater that showed split-reel movies on Kinnickinnic Avenue. “Spencer was always punished by depriving him of things he liked,” Carrie said. “Motion pictures formed a great type of discipline, because refusing to allow him to attend broke his heart.” It was impossible to keep his clothes clean, he rarely wiped his nose, and there were the usual schoolyard fights. “A tough kid,” said Joe Bearman, who lived down the street, “but a good one. Ran with the hard-boiled gang of the neighborhood.”

They tried sending him to Freeport, where he was put to work in the family feed store and enrolled for a short time at the Union Street School. Spencer was kept on a short leash, working at the store before and after class, and it was the structured life in Freeport that likely convinced John and Carrie he would benefit from a more disciplined educational environment. Sometime around 1909—the records no longer go back that far—they turned him over to the Dominican nuns at St. John’s Cathedral, where the consequences of a wayward disposition would carry considerably more weight. He had, by then, started going to Confession and fasting before receiving Holy Communion, and understanding what sin, repentance, and forgiveness were all about. He had also come to see his father’s disappearances as something to emulate, an old suitcase in hand, food, such as it was, filched from the ice box when nobody was looking. He’d get a few blocks out and get hungry, then go a few more blocks and suddenly realize he was out of food.

The school was directly behind the historic church near downtown Milwaukee, a no-nonsense structure of native brick with floor-to-ceiling windows facing east toward the lake. The commute from Bay View was three miles by streetcar, and missing opening prayers would have been unthinkable. Come, O Holy Ghost, enlighten the hearts of the faithful… the Lord’s Prayer, the Angelical Salutation, the Apostle’s Creed. Glory be to the Father. O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee. Two hundred minutes a week were devoted to the study of Christian doctrine and Bible history; only reading, as a subject, was accorded more time. Geography, arithmetic. Penmanship. Composition and recitation, phonics and hymns. There were prayers before and after meals, prayers at the end of the day. O Mother of the Word Incarnate, despise not my petitions, but graciously hear and grant my prayer… “He remembered this nun,” said his cousin Frank. “He said, ‘If you did anything wrong, out with the ruler—bang!—across your hands. If you said anything, you’d get another one. You feared those nuns. They were tough.”

He made no secret of his love for the movies, but it was the church that gave him his first taste of performance. Serving Mass, the phonetic Latin and ritual movements of the altar boy, donning costume in the sacristy, starched collar and lace surplice. “I couldn’t keep an unlit taper in the house,” Carrie Tracy told an interviewer. “Directly after school, Spencer would race home and arrange the candles in every room. Then he would practice lighting and extinguishing them for hours.” He caught the five-cent show at the Union Theater, where the proprietor seated his patrons on ordinary chairs and the ticket girl sang and played the piano. At a capacity of 275, the Union, which offered “high class vaudeville” and a change of program every Monday and Friday, was intimate enough for card tricks and coin manipulations, and it may well have been at one of the Union’s hour-long shows that young Tracy got his first exposure to the art of magic.

“He was a great magician as a child,” his cousin Jane said. “Whenever anyone went to Milwaukee, Spencer did his magic act. Always in the family you did your number, and then you went to your bedroom. He was very good, according to my mother.” He began staging shows in the cramped basement of the family’s rented duplex on Estes, admitting audience members through the cellar door and seating them among the coal bins, the furnace, and the laundry. “Admission was a few pins,” said Forrest McNicol, whose mother ran a grocery store at the corner of Ellen and East Russell. “I guess you’d have to say that was the beginning of the little theater movement in Bay View.” Over time, Spence learned how to manage an audience’s expectations, usually by downplaying the impact of a particular illusion. One safety pin, Carrie Tracy remembered, had the same value as two straight pins, and ofttimes Spencer was accused of overcharging.

Spencer, age twelve. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Soon the wonders of downtown Milwaukee no longer seemed so distant. The grandest of the new movie emporiums was the Princess on North Third Street, which boasted private boxes, a $5,000 pipe organ, and seating for nine hundred patrons. Ads offered a variegated program of comedies and dramas, accompanied by travel talks, scenic views, illustrated songs, and a five-piece pit band billed as “the famous Princess orchestra.” Movies were going uptown and so were the admission prices: the Princess was the first of the Milwaukee movie theaters to charge ten cents’ admission. The following year, the Butterfly—so known because of the huge terra cotta butterfly that loomed over Grand Avenue—went the Princess one better, installing a $10,000 pipe organ and a ten-piece house orchestra. Fortunately, most of Milwaukee’s picture parlors were still nickelodeons, dark and primitive, and it wasn’t hard to find a chase picture or some crude knockabout at half the price the fancy places were charging.

Carroll would soon be starting high school, and John’s bouts with the bottle were growing less frequent. Obsessed with kicking the habit for the good of the marriage as well as his own health, John Tracy moved the family to a duplex on Kenesaw, scarcely two blocks from work, where the floorplan offered no more room than any of their previous locations—two bedrooms, front sitting room, dining area, commodious kitchen—but where the stroll to Bay Street was mercifully unimpeded by the presence of a saloon. Just to the north were wetlands where kids would hang out, marshlands that surrounded an old European-style fishing village at Jones Island. The mill whistles blew at seven and nine-thirty in the morning, noon, twelve-thirty, and five in the evening, and the entire sky lit up when the furnaces were charged.

Over the summer of 1910, Spencer was sent to Aberdeen, South Dakota, where his Aunt Jenny had married a gentle Irishman named Patrick Feely. “He went and played with the wrong kids,” said his cousin Jane, who was Pat and Jenny’s daughter. “He got on the wrong side of the tracks, so it was good to get him away.” Spencer was a spindly kid, delicate and undersized from not eating well. Stepping down from the train, he was greeted by his aunt and her son Bernard, not quite three, who was wrapped around a lamppost and intently staring up at him. “Oh, Mama,” he exclaimed, “he ain’t so homely!”

Over the summer, he also spent time in Ipswich, a one-street town roughly thirty miles due west of Aberdeen, where Frank J. Tracy was editor of the Edmunds County Democrat. Not long after Spencer’s return from Aberdeen, the Tracys moved yet again, this time to lower Bay View. Immaculate Conception was just a block north, at the intersection of Russell and Kinnickinnic, and Humbolt Park, with its playground and clay tennis courts and pond for boating, was four blocks to the west.

The years on Logan Avenue were among the most memorable of Spencer’s childhood, and practically the only ones of which he spoke in later years. He joined the Boy Scouts (“I made a good one”) and kept to his studies. Winters were spent skating, summers playing marbles and baseball. John’s work at Milwaukee Corrugating was secure and valued, and the binges came to a complete halt with the brutal realization that he could never drink moderately. The need never openly manifested itself, but John was always waging the battle, cut off as he was from the society of the tavern. He tried limiting himself to a pint, nursing it as one would a highball, but it was never enough, and all too easy to fall for another. So he cut himself off entirely, strictly limiting himself to work and family and indulging an accelerated taste for sweets. It was a restrictive yet necessary way to live. At times a furious pacing of the floor betrayed the struggle within, and not even Carrie could find a way to comfort him.

Performance, by now, had become routine for Spencer, something absorbing and fun and as natural as breathing. He was involved with the Christmas show at St. John’s in 1911, and at home in Bay View the magic act gave way to more elaborate entertainments “enacting scenes I’d seen in movies.” He staged his first play—a murder mystery—before an audience of neighbors in the living room of the house on Logan in 1912. Having lost himself at the movies, watching the same subjects over and over, he now put himself in the hero’s shoes and imagined himself in the middle of the action. In his own childish way, he was becoming the character he had seen on the screen, and the representation came forth without effort or artifice. “How many times we have told people of that show,” one of Carrie’s friends enthused in a 1931 letter, “proving Spencer was a born actor starting as a child.”

Tracy rarely spoke of these early performances, and although he freely admitted to being fascinated by moving pictures, it is impossible to say just how much live drama he consumed as a kid. Neither of his parents was a dedicated theatregoer, and the legitimate playhouses—the Shubert and the Davidson—charged as much as $1.50 a ticket to see the likes of Ethel Barrymore and Otis Skinner in weeklong stands. The Pabst Theatre, designed on the order of a European opera house, offered German-language programming almost exclusively. The Crystal, Empress, and Majestic were all vaudeville houses, although it was possible to see someone like Mme. Bertha Kalich headlining in a one-act play. The Gaiety was given over to burlesque, leaving the Saxe, Juneau, and Columbia to the ten-twenty-thirty tradition of stock. The plays were things like The Little Homestead and Mrs. Temple’s Telegram and Caught with the Goods, blood-and-thunder melodramas where a seat in the balcony could be had for a dime.

Spencer welcomed his twelfth birthday with particular enthusiasm because it made him eligible for a permit to engage in street trades. Most kids distributed handbills or sold newspapers—the Milwaukee Journal, the Evening Wisconsin, the Leader—but sensing, perhaps, too much competition in the hustling of papers, he managed instead to snag a lamplighter’s route when he was, as his brother put it, “scarcely tall enough to reach the lamps with a burning taper.” Using the tip of a five-foot pole to open the valve on a light, he would hold a match aloft to ignite the gas. “He had about 50 lamps to light each night and to extinguish each morning,” Carroll said. “He also had to see to it that the wicks were in good order, and on Saturdays he had to clean the globes with old newspapers. For this job he received around $3.50 a week, if I remember correctly.”

After ten years of service, John Tracy left Milwaukee Corrugating sometime over the summer of 1913, and the family departed Bay View for Milwaukee proper. The move must have been for the better, for the family relocated to a fashionable stretch of Grand Avenue, almost directly across from the Pabst Mansion and within blocks of the old parish at St. Rose’s, where Spencer would now return for his last two years of grade school. He had to relinquish the lamplighting job, but found work as a towel boy at the Milwaukee Athletic Club, where his father held a membership and where he would learn to box from Wisconsin middleweight Gus Christie. These were, in some ways, the most unsettled years of his young life. The household theatrics ceased, but he never lost that childlike quality, the eagerness to inhabit another skin.

By 1916 the family was renting a Colonial Revival on a tree-lined street in the Story Hill section of Wauwatosa, a bedroom community just west of the Menomonee River. John Tracy had gone into sales as a representative for the Sterling Motor Truck Company, whose plant and offices were nearby in West Allis. The house on Woodlawn Court had three bedrooms, cherrywood floors, and a formal dining room where the Tracys did a lot of entertaining. Spence saw little of Carroll, who had finished high school and was doing clerical work for the Milwaukee Road. He entered Wauwatosa High in the fall of 1915, where, freed from the strict discipline of the Dominican nuns, he failed spectacularly. His only arguments with his father, he later confirmed, were over school. “I might have enjoyed school if I had been doing the thing I wanted to do. My trouble was not having a definite ambition or goal on which to concentrate. I wanted to be doing something that would hold my interest, but I had no idea what it would be.”

He displayed an entrepreneurial streak, and at one point hatched a scheme with a neighbor boy to sell the water they got from a spring under the Grand Avenue viaduct at a nickel a bottle. Significantly, he was returned to St. John’s in the fall, and when his father was asked to take over the Sterling Truck office in Kansas City, Missouri, his only hesitation was over what to do about Spencer. After some inquiries, John enrolled the boy at St. Mary’s Academy, a Jesuit boarding school twenty-five miles west of Topeka, where there would be no distractions from a regimen of study, sports, and the sacraments. Life on the tall-grass prairie must have come as a shock after the comparative excitement of downtown Milwaukee. Separated from his family and friends and limited to just one movie a month, he may well have been tempted to join the boys caught gambling or flagging down cars at the edge of campus, hoping for a ride into town. He lasted just five weeks at St. Mary’s, and no credits accrued as a result of the experiment.

In Kansas City, Spencer was placed at the Rockhurst Academy, another Jesuit institution, where he could go home to his parents at night and where, as he later acknowledged, they took the “badness” out of him “almost immediately.” The Rev. Michael P. Dowling, the school’s founder, named it Rockhurst because the grounds were stony and there was a grove of forest nearby. “I remember Rockhurst as a big building,” Tracy later told the Kansas City Star, “and I remember pursuing to the best of my capabilities the study of Latin and geometry … I also remember that there were some boys at Rockhurst and in Kansas City who were mighty good fighters.”

Official transcripts show he passed first-year Latin, as he did English, Algebra, and Ancient History, and that he did B-level work in Religion and Bookkeeping. The Jesuits were admirable men, spiritual and rigorously educated, and there were few boys who came under their influence who weren’t inspired at some point to consider the priesthood. There was also the bustle of Union Station, fairly new at the time, and Electric Park, with its primitive thrill rides. Most important, he was “almost positive” he saw Lionel Barrymore for the first time onstage, truly a signal event, for Barrymore impressed him as no other actor ever had. He seemed, in fact, to be adapting well to Kansas City when the decision was made to close the Sterling office in the spring of 1917. The semester ended in June and the Tracys eventually returned to Story Park, where they took another house on the same block as before.

The way he remembered it, Tracy first met Bill O’Brien when the two were employed at a Milwaukee lumber yard. “I started for two bucks and a half a week, piling lumber after school,” he said. O’Brien, on the other hand, thought they had met as students at Marquette Academy, and that they stacked wood only on Saturdays. “One of the clearest recollections I have of Spence is of the two of us in dirty overalls and jumpers sitting in the dining room of what was, in those days, Milwaukee’s swankiest apartment hotel. We were stowing away a modest breakfast of grapefruit, ham and eggs, toast, jelly, and milk. At the end of the meal, Spence airily scrawled his signature across the bill and we left.” The Tracys, back from Kansas City, were stopping at the Stratford Arms Hotel, adjacent to the campus of Marquette University. “We worked in a lumber yard to pick up a couple of iron men so we could roister around on Saturday nights. Our breakfasts usually cost more than we made during the day, but Spence’s father paid for them.”

The academy stood on a hill at Tenth and State Streets. It was a block over from the massive Pabst brewing complex, and the smell of hops hung in the air. The location led to the students being referred to as “hilltoppers,” a name that has stuck ever since. “All of us Catholics wanted to enter Marquette Academy,” O’Brien wrote in his autobiography, “but the cost made our parents sigh.” Bill, on a scholarship, was five months older than Spence, taller, darker, rounder, more of a match for Carroll Tracy than for his younger brother. But O’Brien, like Tracy, was “infected” with a love of the stage, and they found time to see such beloved figures as Jane Cowl, David Warfield, Otis Skinner, Lenore Ulric, James O’Neill, and Maude Adams—usually from high in peanut heaven. The great vaudeville attractions of the day came through Milwaukee by way of Chicago—McIntyre and Heath, Harry Houdini, Bert Williams, whose expressive pantomimes were models of economy. A particular thrill came in May 1918 when Madame Sarah Bernhardt headlined at the Majestic and necessitated multiple visits by playing Du théâtre au champ d’honneur during the week and La dame aux camélias on the weekend.

Spence held on to the things that comforted and excited him, and although he was fascinated by vaudeville, his interest in the stage wasn’t reawakened until he and Bill met and they started seeing plays together. The boys may even have arranged their own performances, for E. R. Moak, then city editor on the Milwaukee Free Press (and later a Variety staffer) remembered the first time he met Tracy was when the two of them came to enlist the paper’s support for an “amateur dramatic enterprise” they were promoting. Though Spencer’s grades weren’t as stellar as they had been at Rockhurst, O’Brien was unquestionably a good influence. “Spence and I were a combination,” he said. “He was an introvert and I was an extrovert.” O’Brien went out for sports—baseball, football, basketball—and carried a full load of classes. Tracy worked, played some casual baseball, and eventually took on a class load equal to what Bill himself was tackling. O’Brien went to Mass each Sunday, an acolyte when Spence had long since given it up. Both were restless young men with a war going on, and however much the academy meant to their parents, they had a hard time keeping their minds on their studies.

“I was itching for a chance to go and see some excitement,” Tracy said, and he tried enlisting when the school year was scarcely half over. “I knew very well where there was a U.S. Marines recruiting station, for I’d seen it lots of times before.” He walked up and down Wells Street a dozen times, then went inside. “I want to join the Marines,” he told the gray-haired officer behind the desk, his voice cracking. The man took down his name, address, the answers to a few questions, then asked his age. “I’d been all ready to say, ‘Twenty, sir.’ But he was looking me right in the eye. I stammered out, ‘Seventeen years and eight months, sir.’ The recruiting officer put the form aside, stood, and held out his hand. “Thanks for trying, youngster,” he said.

Spence left the office, as he later put it, “feeling like a chump,” and he said nothing to his family about it. When he celebrated his eighteenth birthday, he was immersed in Greek, Latin, third-year English, History, and Geometry. On April 13, 1918, a hundred thousand spectators lined the curbs as a three-hour parade in support of the third Liberty Loan marched down the center of America’s most German city. The next day, the Whitehouse Theatre on Third Street began a week-long engagement of The Kaiser—The Beast of Berlin (“The Photoplay That Made New York Cheer Like Mad”), kicking off a naval recruitment competition with Chicago that was, by early May, delivering seventy-five recruits a day. The campaign reached its zenith on Mother’s Day weekend, when Lieutenant John Philip Sousa arrived in town with his 250-member “Jackie” band from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. The city seemed to be crawling with sailors, and a half-page ad in the Sunday paper bore the headline: THE NAVY NEEDS YOU! YOU NEED THE NAVY! As Bill O’Brien put it, “The bands played, the drill parades started, the Liberty Bond drives were on, and Spence and myself and some others left school one afternoon and went downtown to the enlistment headquarters of the Navy.”

They didn’t join that day, but they came plenty close. In the O’Brien household on Fourteenth Street, cooler heads prevailed and Bill was persuaded to finish the school year before enlisting. Spence, however, had no wish to continue at Marquette, and the prospect of losing an entire semester’s credits didn’t seem to bother him in the least. That night, as Carroll remembered it, he marched into the kitchen, wearing “that crooked one-sided grin” that had become something of a trademark, and said to his mother, “I’ve enlisted in the Navy.” Carrie instantly burst into tears, but John Tracy “was sort of proud of the kid.” As for Carroll: “I was out of the house and down the street before anyone could stop me. I enlisted too, not so much for patriotic motives, mind you, but because of my desire to be near Spence and to keep an eye on him.” It was Monday, May 13, and naval records show that Carroll Edward Tracy, in one of the few impulsive acts of his life, did indeed sign up for service that day. What he didn’t know was that his brother was merely floating the idea, eager to gauge their parents’ reaction, and that he hadn’t yet done what he said he had done. Once Carroll made his move, though, Spence’s bluff had been called, and he quietly and somewhat sheepishly joined the navy the following day, Tuesday, May 14, 1918.

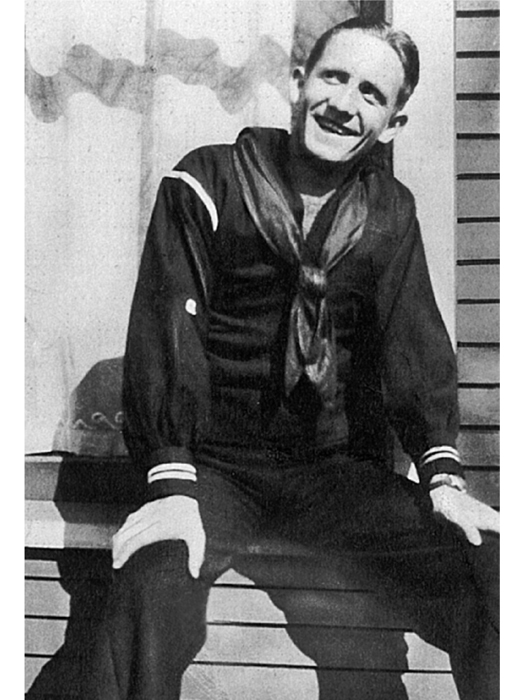

Navy seaman, age eighteen. (SUSIE TRACY)

Enrolled as a “Landsman for Electrician (Radio),” he went straight to school and bypassed boot camp. After vaccinations for cowpox and typhoid, he was sent to the Naval Training Station in North Chicago, where he gallantly spent the rest of the war in a classroom. “The training, the discipline, and the healthy life not only did me good physically,” he said, “but mentally as well. I realized for the first time that a man must make his own way in life, that he must assume certain responsibilities, and that a man can’t receive too much education, because the Navy demands alert minds.”

On the rare weekend when he could get away on leave, Tracy headed home to Woodlawn Court, where, on at least one occasion, he was accompanied by “six of the toughest-looking sailors” Carrie had ever seen. “They were decidedly not what you would call polite specimens of manhood. They apparently were so stunned by our mode of living that they asked Spencer if Mr. Tracy was a bootlegger, and each of them ended up the weekend visit by borrowing $25 from Mr. Tracy. In fact, John used to say it cost him $100 a month, as well as the government its share, to keep Spencer in the service.” After the Armistice, he was sent to Hampton Roads, where Carroll, who spent most of his stretch in Detroit, thought he had some sort of an ordnance job. “I didn’t sleep very well at night because of worrying about him, until I heard through a mutual friend that Spence was doing okay; he was acting as an aide or some such cushy job for an officer.” Bill O’Brien, who waited until August to enlist, never made it out of training.

“When I got into the Navy,” Tracy said, “the least I expected was to see the world through a porthole. As it was, I wound up in a training station at Norfolk, Virginia, looking eastward to the sea and considering myself lucky if they let me go cruising in a whaleboat.” He once made a veiled reference to wild liberties in Norfolk, but remembered the people there with considerable fondness. “They turned that city over to a group of young men who had traveled thousands of miles from home. They made us feel that it was our home. It got us into a couple of rows with authorities, but they understood that it was all in good spirit and never complained. The difficulties weren’t serious, but they would have meant demerits if the Naval authorities had heard of them. They never did.”

Having achieved the rank of seaman second class, Tracy was released from active duty on February 19, 1919, given a sixty-dollar discharge bonus, and sent home to Milwaukee. He later remembered going to work for his father, who was still with Sterling Truck at the time, and it is known that he drove in truck convoys before and probably after the war. “He was a handful when he was a teenager and a little bit older,” his cousin Jane said,

and that was when he was driving these caravans of trucks across the country … He came to Aberdeen the summer I was born, 1917. He said this on many occasions: “If it wasn’t for me she wouldn’t be alive.” Because my mother couldn’t feed me and [when] it was found that I couldn’t tolerate formula, I was sent to the wet nurse. My father had bought a Mitchell car in celebration [of my birth]—because we had all this money from the farms that later collapsed—but nobody could drive the car and he refused to learn. (Eventually, I guess, he figured my mother would learn to drive.) Somehow, they got ahold of Spencer and he came. Of course, he was the car driver and the truck driver in the family. Spencer would drive me to the wet nurse every four hours to be fed.

Neither Tracy nor Bill O’Brien would return to Marquette in the fall of 1919. O’Brien tried law school, but found football more engaging. Spence seemed perfectly happy ferrying trucks across the country, and could have done so indefinitely had his father not wanted a college degree for at least one of his boys. Carroll’s career had ended abruptly in 1917 when he dropped out of Dartmouth, but Spencer, who had excelled in radio school at Great Lakes, still had to get through high school before he could even think of college. He applied to Northwestern Military and Naval Academy with the intention of completing his senior year, and the fact that Dr. Henry H. Rogers, the school’s principal, was willing to take on such an indifferent student was a testament to the academy’s declining enrollment.

Spencer made the connection between Milwaukee and Springfield by rail, traveling on to the city of Lake Geneva via stage. The first look he got of Davidson Hall, the neoclassical edifice which fronted the lake, was from the steamer that connected the city to the academy’s wooded grounds on the opposite shore.

The academic year began on the afternoon of September 24, 1919, as Dr. Rogers began the hellish task of gathering credits from the other schools Tracy had attended. The returns were not heartening. And Rogers was getting conflicting accounts of what exactly the plan was to be after high school. Spencer told him his father had left the “college question” entirely up to him, while John told him he wanted Spencer to go to the University of Wisconsin “at least for the first year.” John, Carrie, and Carroll came for Thanksgiving dinner, but the topic of college was scrupulously avoided. The Christmas furlough was similarly harmonious. Still, Spencer’s grades, while not exemplary, were the best of his life, and after the first of the year, his father was encouraged to aim higher than Madison. He applied to Marquette for war credits to cover the semester left incomplete when his son enlisted in the navy, then wrote Colonel Royal Page Davidson, superintendent of the academy: “Assuming that Spencer applies himself diligently until June and then remains at Northwestern for the summer course, would he be able to establish enough credits to enter the Wharton course at Pennsylvania University?”

At the end of the 1919–20 school year, he had only ten credits toward the sixteen necessary for graduation. John pulled him out of Northwestern and brought him back to Milwaukee, where he arranged for him to do some work at St. Rose’s. What happened that summer is no longer a matter of record, but when Spencer entered Milwaukee’s West Division High School in September, scarcely three months later, he had acquired two additional credits. That fall, he began his senior year in English and Economics, took a Sales course, and excelled at Public Speaking.

By all accounts, Tracy emerged from Northwestern an adult, confident and disciplined. The academy’s geographical isolation and its twin emphases on personal responsibility and scholastic achievement hastened the maturing process. As with Bill O’Brien, he also responded to the influence of a close friend, in this case his roommate, a slender kid from Seattle named Ken Edgers. Two years younger than Spence, Kenny was a friendly sort, uncomplicated and funny, a good student whose interests and habits rubbed off on the more rough-hewn Tracy. The two went ice skating on the mirrorlike surface of the lake, played basketball, spent long hours in study hall. Kenny, a tenor, went out for glee club, while Spence played bass tuba in the school band. Neither was heavy enough for football, although Tracy managed some time in uniform as a substitute. John and Carrie met Ken for the first time when they came to campus on Thanksgiving and were so impressed they invited him to spend the Christmas holidays in Milwaukee.

Northwestern Military and Naval Academy, 1919. (SUSIE TRACY)

Since Seattle was five long days away by train, Carrie told Kenny she would like to be his Wisconsin mother. John was equally impressed, convinced Ken was one of the reasons Spencer got such good grades at Northwestern. He wanted the two boys to continue into college together, but Spencer was, by Dr. Rogers’ reckoning, a full year and a half behind when Kenny graduated in June 1920. So the elder Tracy went looking for schools that would grant war credits, generously and immediately. “During the summer,” Ken said, “Spence’s father wrote to my father suggesting a small college might be advantageous for our college education. It might, he felt, require us to pay more attention to the academic than to the extracurricular activities. He sent information about Ripon College. He felt that Spence would be more anxious to go if I did. So, after considerable investigation and correspondence, our fathers made arrangements for our entrance.”

Kenneth Barton Edgers entered Ripon in September 1920, and Tracy, with an allowance of nine quarter-hours for military service, followed in February 1921. Ripon wasn’t as small as Northwestern and lacked the dramatic lakeside setting, but it was similarly isolated, some ninety miles northwest of Milwaukee on the western edge of the Fox River Valley. The campus was dotted with intimate limestone residence halls, and Spence shared a room with Kenny (who gave him “a tremendous build-up”) on the third floor of West Hall—one of the buildings dating from the time of the school’s first commencement in 1867. He signed up for courses in English Language, History, and Zoology, declaring his major to be Medicine.

“The idea of doing something with my hands appealed to me,” he said, “and I think I might have gone into plastic surgery if something hadn’t happened to make me change my mind.”

1 Daisy Spencer (1873–1963) and Carrie Brown attended Evansville Seminary and were subsequently roommates at Milwaukee College (later Milwaukee-Downer).