I am sure Cromwell will be the first to tell me to go ahead and good luck,” Tracy said in a letter to Chamberlain Brown. “He seems genuinely interested in me and would be glad for my chance. But, he has been very nice to me and I wouldn’t want to hurt him—that’s why I wanted the Cohan thing settled so I could let him know.” Cromwell, Tracy assured Brown, would understand and know that to pass up an offer from George M. Cohan would be crazy. “If necessary,” he added, “I will pay Cromwell two weeks salary, which will break any contract, but I know that won’t be necessary. Cromwell isn’t that kind.” Mr. Wright, he said, felt that as long as he was leaving Lima so early, he would rather have him go right away so that he could save some money by bringing over a man from his company in Pontiac, which would be closing the following week. “Mrs. T. is going on a visit, and I shall come right into N[ew] Y[ork].”

Not realizing his client had actually signed a contract with John Cromwell, Brown advised Tracy not to inform Cromwell of their deal with Cohan. “I sent your wire to Cohan,” Brown explained, “and he did not want Cromwell to hear of this, so that’s why I said so in the wire. He feels it might cause a lot of trouble for him, so be sure you don’t mention it. Of course, there is nothing set with Cromwell so you are protected.” By the time Brown more fully understood the situation, the damage had been done. Tracy was keeping quiet, as instructed, when an item in one of the New York dailies announced the casting of Grant Mitchell, a Cohan favorite, as the star of The Baby Cyclone. “By the way,” Tracy wrote Brown, “this clipping also mentioned me, so I hope Mr. Cromwell doesn’t see it and wonder why I haven’t notified him. However, guess I can explain.”

As it turned out, he couldn’t explain. Cromwell was furious when he saw the news and threatened actions against both Tracy and Cohan. Tracy was unable to mollify him and blamed Brown for the falling out. “After the terrible mess of this year’s contract, which has upset me terribly, lost me one man’s friendship, and nearly lost both jobs, I feel you have too much to do to handle all my troubles exclusively,” he told Brown, distancing himself. “I should like and hope to do business with you as an agent—and will pay [the] same commission as in [the] past.”1

Louise and Johnny boarded the night train to New Castle, Miss Krause seeing them off at the depot. “Well, I guess it’s a good thing you are through,” the nurse told her bluntly. “John will be glad to have you. He needs his mother.” Johnny had just turned three. When they pulled away from the station and it dawned on him that he had his mother to himself once again, his face lit up with both understanding and delight, and Louise figured she had played her final engagement.

Rehearsals for The Baby Cyclone commenced immediately, its first performance scheduled for Atlantic City on August 8, 1927. In the cast were Grant Mitchell as Joseph Meadows, a hapless banker, Natalie Moorhead, his fiancée, and Nan Sunderland, a newlywed named Jessie. Tracy played Gene Hurley, Jessie’s pugnacious husband, a man who buys his wife a Pekingese and then watches helplessly as it quickly takes first position in their marriage. One day, Hurley takes the dog for a walk and gives it away to the first woman who admires it. The ensuing argument between him and Jessie draws in Meadows, a complete stranger, and Hurley gives him a black eye for his trouble. Meadows bundles the hysterical Jessie off to his house, where he learns the woman Hurley gave the dog to was in fact Lydia, the girl he is planning to marry. And, as did Jessie, Lydia babies the dog, whose name is Cyclone because he was born in a storm.

Cohan wrote Hurley as another side of Jimmy Wilkes, the peripheral character Tracy had played so vividly in Yellow. As was Wilkes, Hurley is an accountant, newly married, but where Wilkes’ challenges were desperate and peculiar to a newlywed, Hurley’s are patently ridiculous, and over the course of the play they afflict three generations of households. Hurley was the kind of character Cohan always took for himself—cocky, talented, bound for great things. Sam Forrest was the credited director on Baby Cyclone, but both he and Cohan were concurrently staging The Merry Malones, an elaborate musical in which Cohan was also starring, and the two men worked as a tag team throughout the rehearsal process.

“I’ve forgotten what exactly I did,” Tracy said some thirty years later. “[I] cocked my head over or limped or some goddamn thing, and George M. said, ‘What are you doing? What have you got your head over for?’

“I said, ‘Well, I, ah, Mr. Cohan, I thought I’d sort of, ah, characterize it.’

“He said, ‘You’d thought you’d what?’

“I said, ‘I thought I’d, you know, kind of characterize it.’ ”

“Oh, oh …” said Cohan, now nodding wisely.

“Then he took me aside and said, ‘Now you cock your head back where it was before—when I wrote this part for you. And quit walking with that club foot.’ Or whatever the hell I did. ‘If I want an actor like that I can go out on the street and get five-hundred of them for twelve dollars!’ ”

Once Cohan had Tracy’s attention, he showed him how he himself would play the part, restlessly pacing the stage, his hat cocked down over his right eye, throwing out lines as if they were wisecracks. Mastering the text was easy for Tracy, and although he had the most lines in the play, he considered Grant Mitchell’s part the more difficult of the two. “Listening, to me, is the great art in acting,” he said in an interview.

In five seasons of stock I’ve played a lot of leading men who talked most of the time, but never had to listen. It’s a lot easier to talk than to listen. In this play I talk a lot. Grant Mitchell does the listening … Do you think that I could possibly put over some of my long speeches if Grant Mitchell were not really listening to me? Suppose he let his mind dwell on football games, the horse races, or his supper engagement? Do you think for a moment that I would not feel it and let down unconsciously? And believe me, it would not take an audience many seconds to slump in its chairs and produce a mild bronchitis from first row to gallery top.

Both Spence and Louise grew close to Grant Mitchell, who expressed an uncommon interest in Johnny, and who revealed one night over dinner that his own sister was deaf. “He gave us her latest letter to read,” Louise remembered. “Newsy, humorous, grammatically perfect, it obviously could not have been written by any other than an intelligent, well-educated, and altogether delightful person. I am sure he must have been amused at our amazement and, yes, excitement. To us, still so ignorant of what the future could hold, still so hungry for concrete examples and comparisons, it was manna from Heaven.”

Louise and Johnny went down to Atlantic City for the first performance of The Baby Cyclone and stayed the entire week. The new show brought forth “gales of laughter and storms of applause,” but Cohan nevertheless decided it was too long. The next morning, he was back in the theater “before the janitor” (as Tracy recalled it) and had the entire play revised in the space of six hours. “If an actor didn’t ‘feel’ his lines,” said Tracy, “[Cohan] crossed ’em out and re-wrote them on the spot.”

From Atlantic City the company moved to Boston for four weeks, and Louise and Johnny followed. When Allienne Treadwell learned his daughter and grandson were going to be there, he insisted they see Dr. Harvey Cushing, a noted brain specialist and another of his Yale classmates. Dr. Cushing made a cursory examination of the boy and said he was quite sure there was no brain tumor or other condition he could possibly treat. He did, however, minister to Louise’s spirit, and one thing he said to her would stay with her for the rest of her life: “You are blessed above all mothers. Yours can be a very interesting life.”

The New York opening of The Baby Cyclone took place on September 12, 1927, the show packing snugly into Henry Miller’s 950-seat theater on West Forty-third Street. No construction crews impeded the flow of traffic, and Pat O’Brien, in the midst of a dry spell, was hard-pressed to afford a seat in the balcony. Then, having forgone the expense of a shave, he found it almost impossible to get past the backstage doorman after the show. “And I’ll admit I did look like a bum,” he said.

So [the doorman] wouldn’t pay any attention to me. But finally, he turned his back and I sneaked in. I had heard the doorman telling the boys in the tuxedos and the tails that Spencer’s dressing room was on the second floor, so I went up. But his dressing room wasn’t all I found. I discovered that the son-of-a-gun had a Japanese dresser. This Jap was posted outside the dressing room door, and when I told him to tell Mr. Tracy his pal was outside, he held up his hand in horror. “No—no—go ’way. Room full of nice mans—you go ’way.” I told him I’d start yelling “fire” if he didn’t take my message. So he went inside, shaking his head and muttering. And then you should have seen those “nice mans” come out of there. You never saw so many stiff shirts pouring out of one place in your life. When Spence heard I was there, he told them someone had called that he had to talk business with, and he herded ’em all out. Then he rushed out and grabbed me. He pulled me in and said: “Listen, you mick, what did you think of it? It’s your opinion I want to hear.”

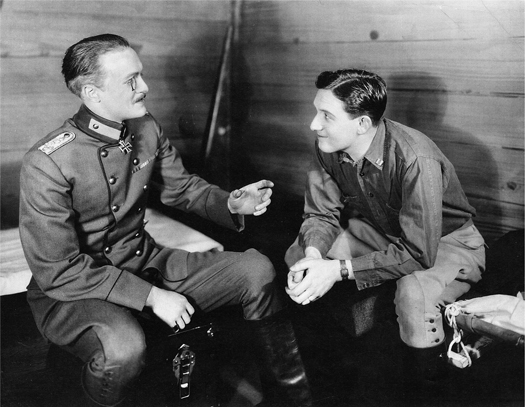

With Grant Mitchell in The Baby Cyclone. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Pat’s opinion was the same as everyone else’s: the show was a scream, an expert farce in which the spirit of George M. Cohan loomed large over the entire affair—his words, his cast, and, in many respects, his presence in the form of an actor named Spencer Tracy. With The Baby Cyclone a hit on Broadway, Cohan brought The Merry Malones in just behind it. A trademark pastiche of sentiment, flag waving, and pure unadulterated hokum, it was crowd-pleasing, if not revolutionary, theater from a master showman. Tracy came to regard Cohan as a kind of spiritual father, a man who recognized his gifts when his own father could not, and who applauded them, at the same time helping to nurture them. “He thought the world of George M. Cohan,” Chuck Sligh said. “He was his sort of hero.”

Tracy marveled at Cohan’s energy and stamina, watching him sit at the piano for five or six hours a day, poking out tunes with one finger, playing a performance in the evening, holding court in his dressing room afterward, and then going home to draft an act in yet another new play. And Tracy’s feelings for Cohan were reciprocated; when Cohan inscribed a picture to him, he wrote, “To Spencer Tracy, A guy after my own heart.”

Deciding they needed more of a home than a hotel room could ever be, Louise persuaded Spence to take a four-room apartment on East Ninety-eighth Street at the southern edge of Harlem—the first they had ever had. For help in furnishing the place, she appealed to the elder Tracys, who had some of their things shipped out from Milwaukee, and to Chuck Sligh, their one lasting friend from the furniture metropolis of Grand Rapids. They moved into their new home on October 10, and presently took delivery of a sturdy new Sligh bedroom set, Chuck having given them the wholesale price—$200. Still, they had to break up the payments to manage the purchase.

Tracy entered radio about this time, for he mentioned working as an announcer for Standard Oil in a couple of early interviews. Radio money would have come in handy, for concurrent with the New York opening of The Baby Cyclone, they enrolled Johnny—at the age of three years and three months—in the toddlers’ program at the Wright Oral School. In the morning session, he joined a group of four other children who were learning to lace and tie their shoes and to sort colored yarn. That same month, Louise made a list of thirty-three words the boy was able to lip-read, among them arm, ball, hat, shoe, soap, pillow, chair, and mouth. A spelling list included nineteen words, and after a little time in school, a list of words he could actually say began with mama, thumb, and lamb. She watched as he would stroke his arm from shoulder to wrist and say arm, then stretch it out toward the coffeepot, withdrawing it suddenly, his eyes full of mischief as he shouted “ot!” (The h would come later.) Over time, pineapple became a favorite word (although it sounded a lot like apple pie). The word fish came out sounding like foosh, and on Fridays Spence took to murmuring, “Ah, foosh for dinner!”

In February 1928 Johnny developed a bad case of the measles, and Spence, upon his recovery, suggested that Weeze take him to Florida. “Florida!” she exclaimed. “He’s in school and he shouldn’t miss any.”

“You can teach him,” he said, urging her along. “He’s so young. The change will do John good and his health comes first. Besides, you should have a trip.”

Louise and John spent most of their days at Miami Beach. “John was crazy about the water,” she said, “and had we stayed another week or two, I think he would have been swimming.”

As his namesake was growing and learning to talk and understand spoken English, John Tracy was slowly fading away. The curious illness that had overtaken him in Milwaukee had been diagnosed as rectal cancer, and the crude radiation treatments of the day were taking their toll on a vibrant and generous man. He worried endlessly about money and his ability to make ends meet. In New York he took a position with General Motors, assigned to the National Account Division, but he suffered bouts of weakness and fatigue, and they were as unhappy with him as he was with them. At the same time he grew enormously proud of his son’s success in New York and his association with the great George M. Cohan. (“He was a long time coming around,” Spence marveled, “but—”) Now practically a Broadway insider, he would stand at the back of Henry Miller’s Theatre every night at 8:25 and count the house. And after the performance the two men would go to supper, arm in arm.

Cohan sold the movie rights to The Baby Cyclone and sent the play out on the road, first to Boston, then to Philadelphia. John regarded Spencer’s absence with melancholy, but Carrie seized the opportunity to fix up the kids’ new place. “I suppose Mother is up at your apartment by this time,” he wrote one morning in a letter. “No doubt she will be busy there for a while, and you won’t know the place … Am going to keep off my feet as much as possible today. I have rather an uncomfortable sensation where the trouble is, and it may be due to too much walking or a reaction from the treatments I have taken recently.” He added: “Don’t forget your Easter duty while in Boston.”

The play’s return to Boston lasted only a week, but Spence took advantage of Louise’s absence to bring Lorraine Foat backstage on opening night. Lorraine had last heard from him in the days leading up to his marriage, when he urged her to come to Cincinnati and apply for a spot with the Stuart Walker company. (“Spence told me to get some pictures and send them along … My grandmother, my darling little grandmother, thought I should have gone, but I didn’t.”) Now Mrs. John Foster Holmes, Lorraine was proud of Spence’s success and anxious to see him.

They talked for a long time—about Cohan, about the theater, about the separate paths their lives had taken. “He adored this son,” Lorraine said, “but felt terribly about it. He suffered over that, feeling that somehow or other he had failed.” Chuck Sligh came to Boston, and comments Spence made to him suggest Louise’s trip to Florida may have been arranged for less than completely altruistic motives. “I think,” said Chuck, “Spence, at that time, probably was … upset … Louise had given over her life to John … He gave me the feeling that she wasn’t too attentive to his needs … I don’t like to put words in his mouth, but the feeling I got was that, ‘Gosh, I don’t know, but Louise is so cold.’ Something like that …”

Tracy came from a tradition, a teaching within the church, that sex within a marriage was solely for procreation, and that recreational sex—the act without the intent or possibility of reproduction—was immoral. “I really believe that it was a very separate part of their lives,” his cousin Jane remarked. “It wasn’t part of the warp and woof of their existence. It was not a natural, normal thing accepted with joy. And I do think, too, that the first result of the sexual act with Spencer and Louise, nine months later, was John—now I think that must have been tremendously traumatic to people of that generation with that kind of background.” Johnny’s birth had come almost nine months to the day after their marriage in Cincinnati. (“Very fast!” Johnny said one day in 1937. “You bet it was fast!” Louise agreed.) “I think that trauma must have led to: ‘Let’s not do this anymore.’ And let’s just not do THIS anymore—not let’s prevent a birth.”

That Spence and Louise still loved and respected and needed each other was obvious to the small circle of friends who knew them both, but the energies and urges normal to people in their twenties and thirties were sublimated, ignored, channeled into other avenues of thought and deed. Louise always tried to be there for him. (“When Spencer played out of town,” she once said, “he needed us with him.”) But Johnny’s schooling made it difficult, if not impossible, to pull up and go, and Spence’s work separated them for weeks at a stretch.

From Philadelphia, where blue laws prohibited Sunday performances, Tracy was able to come home for a day. John looked drawn and tired and anxious to get out of GM. Later, when he was in Chicago and Carroll was with him, John wrote the two of them about a job he was pursuing, concerned his salary demands would discourage an offer. “But I am desperate and nervous and worried so am going to work fast … I haven’t said a word to Mother yet, [but will] tell her in a few days when I know a little more.”

John Tracy, however, was too weak to work, and when Louise and Johnny left to join Spence in Chicago, they did so reluctantly. (“He was a very brave man,” Louise said of her father-in-law. “You would never have known that he suffered at any time.”) The Baby Cyclone enjoyed an eight-week stand at the Blackstone, and from there they went to Cleveland, where Spence would spend most of July playing stock. He returned to New York in late July, where he found himself assigned to the Chicago company of Cohan’s newest play, a turgid comedy called Whispering Friends. His father was wasting away, the cancer by now having metastasized to his liver, and he hated the prospect of being stuck in Chicago. Frank Tracy, John’s half brother, had died the previous month in Aberdeen at the age of sixty-seven, and the dark knowledge of John’s condition enveloped his sister Jenny. “John will be the next one,” she told her daughter Jane.

“He got sick,” Tracy said of his father. “And then he got sicker. Weak. And scared. He’d look at me beggingly—as though I could help if I wanted to. I’d see him wince. Once, visiting, I heard him crying out in the other room … Nothing to do but wait and suffer and wait and wait.” Prior to opening in Chicago, Whispering Friends played a six-night stand in Newark, and Spence made the commute into town by rail. Saturday being a matinee day, he was at the theater between performances when advised of his father’s imminent passing. The news also reached Cohan in Monroe, where his own mother was near death, and at once he came, spending an entire hour alone with Spence, his hand on his shoulder, the call boy pounding insistently on the door. Back in Manhattan, Louise stayed with Mother Tracy at their hotel on East Eighty-sixth Street, stroking her hand. She spent a couple of minutes with John—he was conscious but did not speak—and then left the two of them alone. The end came peacefully at 6:15 in the evening, just as Cohan was racing to Spence’s side.2 Tracy played the performance that night as usual, and afterward found a taxi waiting outside to take him to the station.

They brought John’s body back to Freeport the following Monday, and a viewing was held in the evening at the Wiese & Temple Funeral Church on Main Street. The funeral mass was celebrated at 9:30 the next morning at St. Mary’s on Piety Hill, where John had served Mass as a child and where his father’s altar still stood. Although she and her cousin Frank didn’t have to go to the Rosary, Jane Feely would remember the awful sadness of the place, the black veils all the women wore and the crush of people, the prayers, the eating, the drinking. The cemetery was in the process of being expanded, and there was no space for John in the Tracy plot. Andrew Tracy managed to arrange a temporary grave in the middle of the grounds, and it was there that John Edward Tracy, aged fifty-four years, seven months, and five days, was buried. There would be time for laughter and remembrance afterward, but not for Spence, who had to catch up with the Whispering Friends company in Chicago and give a performance that evening.

It was a blessing for him not to have to go straight back to New York, with its familiar terrain and its constant reminders of his father’s absence. The following day, Andrew Tracy’s wife, Spence’s aunt Mame, brought Aunt Jenny and Cousin Jane in on the train to see the matinee performance of Whispering Friends. Jane was eleven at the time and thought Spence’s tiny dressing room, with its makeup mirror bordered in lightbulbs, nothing short of magnificent. “Did you really think I was any good?” he pressed the women, almost childlike in his need for reassurance, and they both told him he was just wonderful. “Talent isn’t all that you have to have,” he said sagely, echoing one of Cohan’s admonitions. “You have to have personality. That’s the thing that’s important. A good personality.” They talked about the future and where he would go next and how his life had inexorably changed with the death of his father. And then they all sat in his dressing room at the Illinois Theatre and wept.

At length he told them about the previous day, when, arriving at the theater, he saw his name in lights for the first time in his life. At considerable expense, Cohan had wired ahead and ordered star billing, which involved tearing down all the posters around town and putting up new ones that displayed the name of Spencer Tracy in ten-inch letters. The press notices and programs all had to be changed—all in tribute to John Tracy and the tradition that the show must go on and to the fact that his son was now, despite all prognostications to the contrary, a big shot.

To four generations of actors, dramatists, composers, producers, managers, scenic designers, librettists, and press agents, the heart of the Times Square theater district wasn’t Forty-second and Broadway or the Winter Garden or even the stretch of pavement between Forty-fourth and Forty-fifth Streets known as Shubert Alley, but rather a six-story facade of red brick and limestone on West Forty-fourth Street, across from the Hudson and Belasco Theatres, that marked the marble-columned fold of the Lambs. In 1927 the membership numbered some 1,700 individuals—an all-time high—and the clubhouse served as both home and office to virtually every major name associated with the stage—Irving Berlin, Al Jolson, W. C. Fields, Fred Astaire, Eddie Foy, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Will Rogers, David Belasco, and John Philip Sousa, to name but a few.

When actor John Cumberland offered to propose Pat O’Brien for membership in the fall of 1926, the mere suggestion of the honor caught him up short. “I thought you had to spend at least five to ten years on Broadway before this happened,” he said. And when O’Brien, in turn, proposed his pal Tracy little more than a year later, the gesture was no less a matter of gravity. Spence had been Pat’s guest at the clubhouse, had entered the grillroom with its stone floor, its rough-hewn oak tables, its dark-paneled walls, and its huge marble fireplace, and had sensed what it was like to be, in Pat’s words, “A club man, an actor among fellow actors.” He became a duly elected member of the Lambs on December 15, 1927, and managed to scrape together the $200 entrance fee, semiannual dues of $23.33, and 10 percent war tax only with considerable difficulty and Louise’s patient indulgence. And so it was not by virtue of his performance in The Baby Cyclone that Spencer Tracy “arrived” as a Broadway player, but rather by his acceptance into the Lambs as a member, professional class.

When the Midwest tour of Whispering Friends petered out, Tracy returned to New York. Louise was now immersed in Johnny’s studies at the Wright Oral School, so Spence retreated to the Lambs, where he spent his days writing letters and working the phones, a bank of which lined the north wall of the reception corridor. By edict of incorporation, the Lambs never closed. The bar officially served tea and apple juice, but the premium stuff—whiskey, sherry, champagne—was always around, tucked away in someone’s locker or available for purchase from the night doorman. “Dry times or wet, the bar of the Lambs was never raided,” Pat O’Brien said, recalling that the mayor of the city of New York, the honorable James J. Walker, was a loyal member. “We had political power.”

Idle in the midst of a new season, Tracy’s natural bent toward melancholia deepened to the point where he suffered wicked bouts of depression. His self-loathing over his son’s deafness surged at times of inactivity, and his grief over the loss of his father swept over him in waves. One weekday afternoon it took hold of him as he began a routine note to his mother. “Mother dear,” he wrote, “your lovely wire made us so happy, dear. We were going to wire you—thought of it several times—but didn’t know where to send it … We had a dandy dinner and a wonderful time at Ray’s. Spoke of you & dear Dad so much.” And then the pen began to race—page after page—as the pent-up feelings suddenly spilled over.

O Mother dear—I never let you know and never will again how much I miss my wonderful dad. I have come home at night and stood and cried before his picture in our front room. I talk to him many times. He was so good to me—and I know you won’t mind—nor will Carroll—but I always felt he was closer to me than anyone—except you, of course, Dear. He understood me so well, and was so kind and always forgave. Sometimes I want to go with him—I know I’d be all right where he is—and when that time comes, I’ll hate to leave anyone behind but I won’t be afraid, and I’ll be glad because I’m going to see my dad. But we must be cheerful—and I will, Dear. Forgive me for writing this letter, but sometimes I feel I just gotta see Pop—or I’ll go crazy.

It was as naked an expression of inner feelings as he ever permitted himself, but talk of suicidal grief and going crazy could well frighten his mother, and he obviously fought to control the words he was now putting down on the page. “But he is happy now,” he continued, reining himself in, “and he is watching us and taking care of us, and he wants us to do our best and be happy—and we will, Dear. We have lots to live for. Excuse all this, darling Mother, but I guess I’m still yours and Pop’s little boy, and sometimes I get sad—and cry—just like my little boy.”

John Tracy had found such joy in his four-year-old grandson, his little victories and pleasures and the sounds he made to represent words. Around the house, Johnny had names for the people he loved, vocal labels that derived from the words he could say. Mumum was his name for Grandmother Tracy, Mum (pronounced “Moom”) for his grandaunt Emma. One was his teddy bear. His nurse came again in November, the one who had been with him in Grand Rapids and at Lake Delavan, and although her name was Eleanor Lystad, she became Sss at first, then Sis.

Eleanor’s arrival, along with the costs of the Wright Oral School, put yet another burden on the family finances. Spence scared up a week of stock on Long Island, but was forced to borrow $1,000 from his mother until he could find steadier work. He gave her an IOU at 6 percent interest, but the whole matter upset Carrie so greatly she worried that Spencer would be unable to support his family. Then Johnny broke his leg, the result of a fall while playing in the park, and was in the hospital for six straight weeks. Arrangements had to be made for one of his teachers to go to his bedside for a short period each day to keep up his speech and lipreading, which otherwise would have suffered sharp relapses.

Pat O’Brien saw enough of Spence at the Lambs—too much, for he too was out of work—to know the spiritual toll unemployment was taking on his old friend. “An unemployed actor becomes a different person,” he said. “His morale sags, he wears a haunted look. The burden of the ages sits on his shoulders as he gossips with other unemployed actors.” When Lester Bryant, a brother Lamb who was married to actress Edna Hibbard, announced one day that he was going to organize a new stock company, Pat walked him around the clubhouse until he had engaged practically his entire company—William Boyd, Frank McHugh, O’Brien himself, Tracy, of course. Spence had sworn he wouldn’t play stock again that winter—had, in fact, turned down a season with the George Cukor company in Rochester—but he was plainly out of options and desperate for income. O’Brien, McHugh, and he performed in the Lambs Kid Gambol on December 16, then passed the hat for traveling money and entrained to Baltimore, where the Auditorium Players would open Christmas Eve in a gangster melodrama called Tenth Avenue.

Nineteen twenty-eight had been a rough year, but 1929 would be rougher still. The run of the Auditorium Players lasted just three weeks. (“But,” said Frank McHugh, “it was a rip-roaring three weeks!”) Leaving Baltimore put Tracy on a seemingly endless rotation of two- and three-week stands, unsure of where his next job would come from, breathing life into mediocre material and occasionally making it sing. Returning home to New York, he wired his mother in Freeport and said that he had “several things in view,” and did in fact land a part in a play called Scars on February 6.

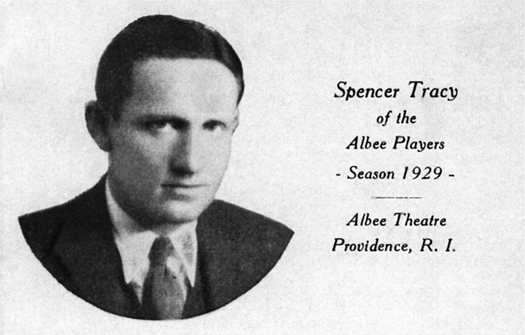

With Albert Van Dekker in Conflict, 1929. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Backed by New York retailer Hiram Bloomingdale and authored by Warren Lawrence, the brother of Boston golf crack and playwright Vincent Lawrence, Scars ran the arc of an American serviceman’s career from draftee to flight commander to peacetime has-been. Out of town, the lead actor had been a toothy twenty-seven-year-old named Clark Gable. He was well received, giving, in the words of one critic, “a true-to-life picture of a man who hit heights of glory and then slid to the bottom of the pile.” The play was choppy, though, full of awkward stage waits that undercut the psychology of the piece. “I didn’t like my part,” Gable later said. “I hadn’t been able to get anything out of it. In Springfield I handed in my notice; I wanted to leave just as soon as they could get another actor up from New York to take my place—and it couldn’t be too soon to please me.” Tracy stepped into the role of Richard Banks with little rehearsal and suddenly the play, no masterpiece but with flashes of near-brilliance, began working as never before. Retitled Conflict, it was brought to the Fulton Theatre on March 6, where critics saw an uneven but sincere piece of work, elevated by Tracy’s masterful performance and supported by an exceptionally capable cast consisting of Edward Arnold, Frank McHugh, George Meeker, and Albert Van Dekker. “The final impression,” J. Brooks Atkinson wrote in the Times, “is of a genuine character portrait surrounded with disenchanting chromoes. What Mr. Lawrence and Mr. Tracy have done with Richard Banks deserves a more harmonious setting.”

No one thought the play a disaster, but the fact that it needed work was indisputable. Tracy thought Banks the strongest part he had yet played before a New York audience, and when the author announced his intention to revise the play over a Holy Week recess, Spence joined him in making the rounds of the various dailies, going from one drama critic to the next, notices in hand. Conflict hit the boards again on Monday, April 1, and the critics were invited to come take another look. Regrettably, the play wasn’t much better than before, but virtually every critic gave it a kinder notice. Trade improved slightly, but the company managed to survive only on cut rates.

Conflict closed on April 27, 1929, and Tracy went almost immediately into rehearsals for an ill-fated comedy titled Salt Water. They tried it out in Mamaroneck, where it was well received, then moved it to Atlantic City, where, despite sterling reviews, the play’s coauthor, actress Jean Dalrymple, concluded her lead actor had “no sense of comedy.” She pushed director John Golden to replace him with actor Frank Craven. “So there we all were, down in Atlantic City, and the show went very well. But, of course, Tracy was really heavy in the part, and afterwards Frank Craven said, ‘Oh, I could really play that part. I could play the hell out of that part.’ So Golden closed the show and let Spencer go.”

Smarting from such a summary dismissal, Tracy returned to Manhattan in a surly mood. Broadway had suffered its worst season in nine years, due largely to the proliferation of talking pictures. Dramatic stock wasn’t doing any better against the onslaught of amplified dialogue. Two years earlier Tracy had advised Chamberlain Brown he was playing Lima strictly for the money. “Next season,” he said, “I should have a nice bankroll, and I hope this will be the last time I have to do stock—unless it’s a real good one.” Now, miraculously, a real good one presented itself, almost on cue.

Selena Royle had settled into a pattern of playing summers with the Albee stock of Providence, Rhode Island, one of the top two or three companies in all of North America. When the company’s leading man, Walter Gilbert, quit early in the season, she naturally thought of Spence. “By this time,” she said, “we had played together so often that we automatically knew what to expect of the other on stage—a great advantage in stock, especially in Providence, where we played five matinees a week … So, on my recommendation, Spencer was sent for.” Tracy settled in for the remainder of the season, taking a house for the summer that would give Johnny the experience of having a yard of his own. His debut at Providence was in a four-act mystery called The Silent House, and while he was universally well received, nobody mistook him for a traditional leading man.

(SUSIE TRACY)

“There is nothing stagy about him,” the critic for the Providence Journal declared. “No makeup—none to speak of—no tricks whatever; just an unassuming, easy manner that gets him about the stage without your quite knowing how he does it. He belongs to that school of acting—if it is a school—which doesn’t want you to think it is acting. It is acting, though, of a very high order, forceful, reserved, artistic.”

It looked as if the season at Providence would be a triumph, and Louise happily settled into the relaxing routine of managing her own house. “Upstairs and down, outdoors and in, John would trot. The freedom of it all was a constant wonder and delight after hotels and apartments and Central Park, with its KEEP OFF signs dotting its hundreds of acres of grass and its policemen whose main job seemed to be to enforce those warnings.” The ensuing weeks brought The Second Man and Night Hostess and Skidding, and while Tracy was always a hit with both audiences and reviewers, an uneasiness crept into the atmosphere of the company, as if there was a subtle malfunction that nobody could quite place a finger on. It was likely Tracy’s spoof of John Barrymore in The Royal Family that sealed his fate.

Tracy blamed Albee’s general manager—a man called Foster Lardner—whose sense of material was seemingly infallible but whose ideas of what actors were suited to what parts were rigidly traditional. Tracy was a fine actor, Lardner acknowledged, but lacked the profile of a leading man. “The women don’t want to come to see you at the matinee,” he told Tracy in letting him go, “but it wouldn’t surprise me if someday you became a great motion picture star.”

“How the hell can I do that,” Tracy responded, “if I don’t have any sex appeal?”

He was terminated with two weeks’ salary and spent much of August at liberty, waiting for the new season to come together in New York. He spent his afternoons at the Lambs, saw Johnny principally at dinner and on Sundays. All sorts of projects took shape at the club—ideas for plays, songs that needed writing, schemes to keep working. A year earlier, Jack McGowan had formed a loose partnership with Joe Santley, who was secretary of the club, and Theodore Barter, to produce their own plays and the plays of brother Lambs. In October they had signed Tracy to appear in a postwar tragicomedy McGowan was writing called Nigger Rich. Spirits ran high until the first production of Santley, Barter & McGowan hit the boards, a melodrama from Johnny Meehan titled The Lady Lies. It lasted twenty-four performances, putting a quick end to plans for the McGowan play until Lee Shubert embraced it the following summer.

Retitled Parade, it had a week at Greenwich, where Chamberlain Brown had a stock company. Shubert thought the play had potential, but butted heads with the author over its provocative original title. Unilaterally, Shubert changed the title to True Colors, a move which so incensed McGowan that he threatened to withdraw it. Shubert backed down, but the staging of the play by its headstrong author was, by common agreement, careless at best. After one invitation-only preview, during which the crowd’s mood went from hope to despair, it premiered at the Royale to largely negative reviews and was yanked after eight days—something of a record for the distinguished members of Cohan’s inner circle.

Tracy had plans to step away from Nigger Rich before the white slip appeared on the call board, as Sam Harris had contracted him for a play called Dread. The work of Owen Davis, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of nearly a hundred plays, Dread was the aptly titled study of a young man’s disintegration into madness, a graphic look at how the caustic effects of fear and a guilty conscience can do both emotional and physical damage to a man. Tracy, with the highest of hopes for the role, began rehearsals under the author’s direction on September 30, Madge Evans, Miriam Doyle, and Frank Shannon working in support. The first performance took place at Washington’s Belasco Theatre on the night of October 20.

There were no real heroes in Dread, only the amoral Perry Crocker and a pair of willing victims. On the eve of Crocker’s wedding to the frail Olive Ingram, he declares his love for Olive’s younger sister, Marion. Then Crocker’s wife appears at the door and tells Olive of her son by him and his subsequent desertion of the family. The shock of it all brings on a heart attack. Olive’s dying words to Perry: “You’ll—never—have—my—sister—living or dead. I’ll stop you—some way—some how—you—can’t—have—Marion!” Then, clutching his wrist, she falls back in the chair, her fingers locked in a death grip, Perry unable to pry himself free. He lies to Marion, tells her Olive has blessed their union, but Marion knows better. “When I go with you—and I am going—I will be as degraded as you are.” Perry is tormented by Olive’s death, her vow to him, the memory of her cold, rigid hand refusing to let him go. He flinches at sounds in the house, sees Olive’s form in the shadows, deteriorates into a pale, quivering shadow of his former self.

Great things were expected of Dread, the most ambitious play Davis had written since Icebound, the one that had won him the Pulitzer. The Post’s John Daly hailed the playwright’s return to melodrama, the boldness of his contrivances, the stunning fact that the old master’s theatrics “spit fire and cause squirmings in the orchestra chairs just as his earlier works did when they played on the old Stair and Haviland circuit in the ‘ten-twent-thirt’ days … Mr. Tracy stands up nobly under the punishment, a villain who makes you want to shoot him in the back or kick him in the trousers every time he turns around—so that by the end of the night you expect to hear hisses.”

Harris had planned to move the company to Philadelphia, but a musicians’ strike intervened and the play landed instead in Brooklyn. Stopping at the Lambs, Tracy was asked by Ring Lardner, the renowned author of Alibi Ike and Haircut, what he was doing. “I told him,” said Tracy, “I was going to Brooklyn with Dread and he said, ‘Is there any other way?’ ”

Lardner’s disdain notwithstanding, Dread managed to fill the 1,700-seat Majestic on a Monday night. “In the parlance of the stage,” said the notice in the Brooklyn Standard Union, “overplaying a part means ‘taking it big,’ mostly concerned where grief and semi-madness are the expressive emotions. Dread calls for both emotions in a large measure. Spencer Tracy and Miss Madge Evans play the two important characters with proper reserve. Others might have ‘taken it big’ and ruined what is now a most thrilling piece of drama … The audience called for ten final curtains, which speaks for itself.”

The strong responses in both Washington and Brooklyn would have assured a place for Dread on Broadway but for the fact that the play opened in Brooklyn on October 28, 1929. The next day—October 29—would go down in history as Black Tuesday, the day when huge blocks of stock were thrown on the plummeting market, and paper millionaires were rendered penniless in the space of a few hours. Sam Harris, his funding uncertain, sent both Dread and the promising Swan Song (by the surefire team of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur) to the storehouse, hinting the Davis play “may be rewritten” but ultimately allowing only one Broadway production to go forth under his management in the year following the crash. The Brooklyn performance of Dread on the night of November 2 was the last ever given anywhere. Louise disliked the play, its obvious hokum, and thought it deserved to close, but Spence was bitterly disappointed and always carried the lingering suspicion it would have made him a star. In May 1940 he lamented its disappearance to Halsey Raines of the New York Herald Tribune, saying that the property he was “most enthusiastic” about, the one he was sure would have been “a box office sensation” had it come to Broadway, was an obscure but singularly nerve-racking play called Dread.

“Now we sometimes laugh about Dread,” Louise later wrote, “and Spencer will relate with great gusto how the family nearly was broken up, of how his mother demanded that he leave the stage and get a job whereby he could be sure of supporting his wife and child, and how his wife said if he left the stage she would leave him. But at that time it was not so funny.” In the wake of the stock market crash, Mother Tracy took note of the fact that her son had worked eight jobs in the fifteen months since the close of The Baby Cyclone. An actor wasn’t paid for up to five weeks of rehearsal, and during the first two weeks of performance a show could close without any notice, making it very possible to earn just two weeks’ salary for six or seven weeks’ work. There was also the traveling, and even among the luckiest of actors there were periods before and after when no money at all was coming in. “Even to approximate foresight to any degree,” Louise said, “an actor should divide his weekly salary into tenths, living on one-tenth and banking the other nine to fortify those unproductive ones.”

When playing, Spence was earning as much as $400 a week, but with layoffs and rehearsals factored in, his earnings came closer to $150 a week. So when Mother Tracy raised the subject as forcefully as she could, the best answer her son could give her was “Louise said she’d leave me if I quit the theatre.” Late in life, Louise wasn’t so sure she had ever put it exactly that way. “I don’t remember saying quite that,” she said, “but I might have, because I felt that Spence must do the thing he could do so well.” In 1942 Pat O’Brien recalled witnessing the exchange, which was sparked, as he remembered it, by his suggestion, during a particularly lean period, that both he and Spence call it quits and go back home to Milwaukee and settle down.

Louise flamed. She was always a good actress, but she never put as much emotion into any role as she did in her reply to my suggestion. “No!” she blazed to Spence, ignoring me. “If you give up the theatre I’ll leave you. You’re not a good actor, you’re a great actor! I don’t mind going hungry. I don’t mind doing our laundry. I don’t mind any sacrifice because you have something not one actor in ten-thousand has, and the day will come when you’ll be acclaimed the finest actor on the stage! I’m not only willing but eager to do anything I can to help you toward that day. But DON’T QUIT. You CAN’T.” It isn’t often a man finds someone with that much confidence in him.

After the folding of Dread, Tracy was out of work a full three weeks before he picked up a job replacing Henry Hull in a Jazz Age tragedy titled Veneer. Hull, the nominal star, had decided to leave the show in favor of A. A. Milne’s new comedy Michael and Mary; Tracy stepped into the role of a smooth-talking braggart with less than a week’s rehearsal. Nobody expected it to last very long, but a deal was afoot for the Shuberts to buy in and take the show to Chicago, where fresh casting, slick staging, and a new title might possibly save it. Louise, who read all of Spence’s plays, thought Veneer “an unpleasant play, though very moving at times.” It gave Tracy a chance to wear—and pay for—the expensive wardrobe he had bought for Dread. It was a star part, and for the first time in New York his name would appear in lights on a theater marquee. Most important, it was a job at a time when nearly a third of all the theaters on Broadway were dark, and the new slogan along the big street was “Got change for a match?”

Hull played his final performance on Saturday, November 30, and Tracy stepped into the role of Charlie Riggs two days later. He played a week, then followed the show into an Equity-approved layoff, the Shuberts guaranteeing salaries while they moved the physical production to Chicago’s Garrick Theatre. It opened there on December 20 under the title Blue Heaven and was largely savaged by the critics.

Back in New York, things were particularly grim, with nearly a score of houses lacking legitimate plays. The few genuine hits—Strictly Dishonorable, June Moon, It’s a Wise Child, Berkeley Square—were gobbling up much of the available business, and the holiday spirit was so lacking along the street that the “merchandise” men who supplied wet goods to the Times Square theater district were forced to accept installment payments to move inventory. That Tracy was able to get himself cast in a new play titled All the World Wondered was something of a miracle. The play wasn’t promising—an all-male cast in a decidedly raw portrait of life on death row. They played three days in Hartford, where the audiences were, in Tracy’s words, “as cold as the Yukon.” He wasn’t in a particularly hopeful mood when his pals at the Lambs next saw him, glum and sagging. “He was a pretty disconsolate guy,” Pat O’Brien remembered. They were all sitting at the round table in the grill.

“Boys, I’m in one hell of a flop!” Tracy announced to the group. “I’d like to pull out, but I have a run-of-the-play contract.”

“What do you mean pull out?” someone said. “Stay with it.”

“It’s to have a week of doctoring,” Tracy told them, “and then open on Tuesday.”

“Maybe you’ll get a break,” another suggested helpfully, “and the theater will burn down.”