It was a measure of her despair over the winter of 1933–34 that Louise Tracy was willing to leave the children—year-old Susie and, particularly, John, the focus of her life—in Spence’s care and go off to New York with no specific plan in mind and no date set for her return. She was obviously hurting, humiliated, and maybe even a bit angry, but to all who saw her, the few friends she allowed into her life, her mother-in-law, the servants, John’s therapists and teachers, she was calm, collected, the very picture of reserve and forbearance. She had seen her own father walk away from her parents’ marriage in much the same way that Spence now seemed to be walking away from theirs. He put it on her to divorce him if she saw fit, knowing she was perfectly within her rights to do so, knowing that he himself could never take the step of divorcing her. She had never given him any cause to do so, never would. What they said in public was remarkably candid and true; what they said in private is anyone’s guess.

Louise had longed to take up polo, but Spence was against it, seemingly jealous of his time alone on the field and disapproving in general of women in the game. Then it became a discussion of Western saddle—which Louise knew—versus the lighter, hornless English saddle used in the game. It would be like learning to ride all over again and entirely too dangerous. “He said, ‘You aren’t going to do that,’ and I said, ‘Well, everybody else here is doing it.’ ” One afternoon Snowy Baker talked her into trying it, and Spence had a fit. “I can’t see any harm in stick-and-balling,” she said, employing the term for simply working out on a pony. He thought for a moment and then allowed as how he supposed not. She borrowed one of his hardwood mallets, awkward and unwieldy, and began taking lessons, marching past the grooms at the stables with as little self-consciousness as she could manage.

Louise had ridden White Sox on picnics into Mandeville Canyon, on Saturday morning rides with the children, and on moonlit outings up into the hills and across Will Rogers’ ranch. She had watched with growing envy the women who played in the mixed games on the dirt field. “Never have I seen women have as much fun at any sport—at anything—as the women I watched at Riviera,” she wrote. “There were times when I thought them nothing more than mad, and others, nothing less than goddesses. Grimy goddesses, I grant you—grimy but glowing. One can’t leave a dirt field after six or eight chukkers and still hope to resemble ‘what the well-dressed sportswoman will wear.’ At last, when I could bear it no longer, I determined, if possible, to sit with them—or play with them—upon Olympus.”

She was immediately embraced by the women who played the dirt field, who occasionally mixed it up with the men and sometimes even won. She made her best and most lasting friendships at Riviera—Lieutenant and Mrs. Gilbert Proctor, Audrey Caldwell, Walt and Lillian Disney, a Mrs. Chaffey (a full generation older and still playing), Mr. and Mrs. Carl Beal, Audrey Scott, the screenwriter Mary McCall. After a few lessons, a group of them corralled her in the office: there was a mixed handicap tournament starting, and they needed more women.

“Feeling far more mad than goddess-like,” she said, “I finally agreed to play. From the moment of the first throw-in when, as No. 1,1 I knew just enough to turn and ride toward our goal and heard the thunderous pounding of racing hoofs behind me, to the last gasping moment and I slid from my horse—Spencer’s horse—at the end of the game, it was more fun than I ever imagined.”

Spence was amused and even grudgingly pleased when he learned of Weeze’s debut on the field, and soon she had a pony of her own, a little brown horse named Blossom. And where Spence found exhilaration and exercise and release on the field, now so did Louise, and it meant a lot to her when she showed up the day after the news of the separation hit the papers and not one of her fellow players mentioned it. “No one asked any questions and no one appeared interested.”

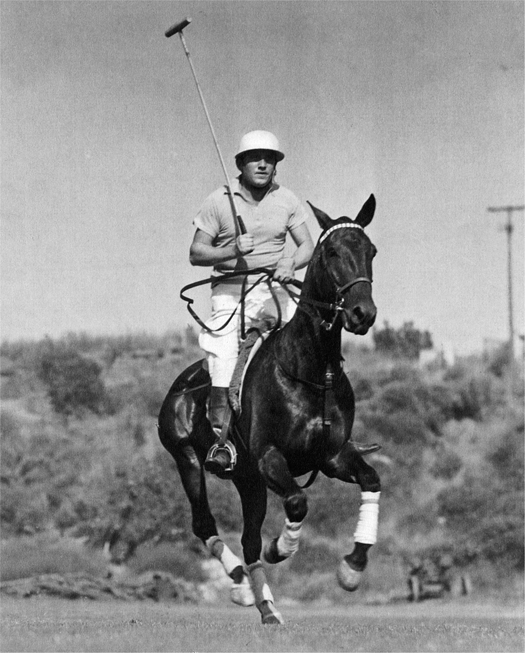

Tracy relished his time on the polo field but thought the game too dangerous for women. (SUSIE TRACY)

She played furiously that fall and in January announced that she and Audrey Caldwell, a former actress, like herself, who had married an actor, would give California the first women’s polo association in the United States. Teams from San Mateo, Santa Cruz, Santa Barbara, Fullerton, San Pedro, and Long Beach were expected to throw in, and Snowy Baker opined that the better female players were equal to the one-goal players on the men’s teams.2

Louise began writing a play as well, a caustic comedy in three acts about a philandering husband having a very public affair aboard an ocean liner bound for Honolulu. Titled That Broader Outlook, it gave her a chance, via the character of Jane Stafford, to explain herself, to show the world what she was up against. It also contained a wry portrait of Mother Tracy, appalled by her son’s behavior but sure Jane’s mishandling of the situation was part of the problem. When the ship’s doctor suggests her son is a great deal like his father, always a good fellow, open and aboveboard, Abigail Stafford replies, “In most ways he is. He’d be more so if … if he had been managed differently. There’s no use talking, women aren’t the wives they used to be.”

Assertive and opinionated, Mother Stafford takes Jane to task for sitting “like a bump on a log” while Mrs. Darling beguiles her husband “into all kinds of foolishness without raising your hand to stop it.” She warns Jane, “He’ll fall in love with her if you’re not careful.”

JANE

Oh, no, I think not.

ABIGAIL

Well that’s all you know about it. He kisses her.

JANE

No doubt. It requires no beguiling for Jack to kiss pretty women. I don’t suppose there is room on this steamer, steerage and lifeboats included, to hold all the women Jack has kissed in the last ten years, and his yearly average is decidedly on the increase.

Jane is patient because she knows she shares the blame, but not quite in the way her mother-in-law thinks. “I haven’t a doubt,” she says, “that I’ve failed in many ways to be a good wife. That is only another reason I do not feel qualified to dictate Jack’s code of behavior.”

In the first place, I’m not losing Jack’s love, and I would lose it if I nagged and made scenes. Jack hates unpleasantness, he simply runs from it. If I made our relations quarrelsome or unpleasant, he would begin at once to deceive me, and I prefer to have his confidence, even when it hurts, than to be contentedly deceived.

ABIGAIL

Confidence? I guess confidence isn’t what it used to be, any more than love is. Do you mean to tell me that Jack has confided to you all the times he has kissed this Darling woman?

JANE

Not in detail, I’ll admit. He didn’t come down last night and say, “Well, I kissed Mrs. Darling thirty-seven times.” But he indicated that her romantic intensity was well sustained. He said, as I remember, that she was a handful. His endurance is never alarming. He will be relieved when she goes on and we stop in Honolulu. You see, in Jack’s code of behavior, flirting is a pastime and has no bearing on our real loyalty as man and wife.

To his mother, Jack explains his tomcat ways in terms of compatibility, much as Louise had put it to Dick Mook.

JACK

Jane and I understand each other all right. You don’t realize people look at things differently than they used to. Jane’s no end highbrow and prosy. Now don’t misunderstand what I mean—I wouldn’t have any other wife in the world, and she’s a wonderful mother; you know that. But we have each got to interest ourselves in our own way. We’re an institution, not a jail.

Louise got just twelve single-spaced pages into That Broader Outlook before giving up on it, unsure of where she was going and knowing it cut too close to the bone to ever be produced. She put it away, along with her poems and her clippings, but she never destroyed it.

Marie Galante was set to start on Wednesday, June 27, 1934, but calls to Tracy’s fourth-floor suite at the Beverly Wilshire went unreturned, and he failed to show for costume fittings and a conference with director Henry King. On the night of the twenty-sixth—Johnny’s tenth birthday—Fox legal counsel George Wasson went to the hotel with a letter over the signature of studio manager Jack Gain directing Tracy to report to King at ten o’clock the next morning to begin work on the picture. At suite 412, Wasson was admitted by Wingate Smith and an older man whom Wasson did not identify. Smith was Jack Ford’s brother-in-law and longtime assistant, a well-known and well-liked figure around the Fox lot.

“Mr. Tracy at the time was in bed, asleep, and apparently in no condition to be disturbed,” Wasson recounted in a memo for record. “Mr. Smith informed me that Mr. Tracy has been suffering from an excess consumption of alcohol, and from a lack of proper food and sleep; Mr. Smith also informed me that he had been in constant attendance upon Mr. Tracy for a period of approximately two weeks and that, although Mr. Tracy was not in a condition of continued unconsciousness, Mr. Tracy was, even in his waking, conscious moments, unable to control his physical and mental coordination.”

At the time of Wasson’s arrival, Smith had already summoned a doctor, who planned to give Tracy a hypodermic so that he could be removed to the hospital and given the constant care and attention required to “restore him to his normal faculties.” Wasson waited until the doctor arrived, approximately twenty minutes, then attempted to speak with the patient.

When Mr. Tracy awoke, he was apparently conscious, but in a semi-dazed and incoherent condition, being able to speak only a part of a sentence without his mind wandering to some other subject or failing to operate entirely. Mr. Tracy seemed to be laboring under some great mental stress and I endeavored to find the cause but was unsuccessful. I advised Mr. Tracy that it was our desire to have him report to our studio the following day and he informed me that he would not do so. I then told Mr. Tracy that I came to present him with a notice to report and proceeded to read the attached notice to Mr. Tracy.

At the time of this conversation with Mr. Tracy, he had requested the other persons present to leave the room so that he could talk to me alone. He finally started to tell me what he desired to say and after several unsuccessful attempts he discarded the idea in the middle of a sentence and rolled over and proceeded to go back to sleep, thus ending the conversation.

The doctor tried to get him to take the hypodermic. When he refused, the ambulance attendant was summoned, and it was he who managed to get the patient to his feet and down the elevator to the ambulance, which was waiting in the garage. The doctor assured Wasson that Tracy was in no condition to work and would be unable to work for several days. The next morning, Tracy was removed from the studio payroll.

Marie Galante had the reputation of being a jinxed picture. It had been in the works, off and on, for two years, the book on which it was based being an international best seller. The tale of a shanghaied prostitute making her way across Central America, it seemed to Winnie Sheehan the ideal vehicle for Clara Bow (though no one could reasonably expect her to affect a French accent). They were ready to go with a script by Dudley Nichols, Tracy up front as Crawbett and William K. Howard directing, when Bow, suffering increasingly from the chronic depression that would soon end her career, backed out. The picture was shelved until Sheehan saw actor Miles Malleson’s adaptation of the German war drama The Ace in London and was taken with the performance of French chanteuse Ketti Gallian. Just twenty, Gallian played her entire role in French and required a translator to converse with the cigar-puffing studio boss. When she arrived in Hollywood on Christmas Eve, 1933, she knew barely half a dozen words of English and had virtually no experience in front of a camera.

Playing opposite Clara Bow, still a big box office name, was a vastly different proposition from propping up a newcomer, and Tracy came to regard Marie Galante as a throwback to the days of Society Girl and Painted Woman, when the purpose of the picture was to showcase the girl and he was kept offscreen until the second or third reel. Sheehan had Sonya Levien and Samuel Hoffenstein do a polish on the Nichols screenplay, revising Marie’s lines so that a non-English speaker could handle them, and then Henry King had suggestions when he came aboard as director. Reginald Berkeley, known for his work on Cavalcade, did his own version of the script, juggling concerns from the German, Japanese, and Panamanian governments over how their nationals were to be portrayed. Subsequently, Berkeley’s work was enhanced and emended by John Zinn, Jack Yellen, and Seton I. Miller. All told, twelve writers had a hand in rendering Marie Galante completely unrecognizable by the time it reached the screen.

When Tracy was carted off to the hospital the day before filming was to commence, it was agreed he would be unable to render services until the second week in July and his contract was extended accordingly. The picture was held, even though Henry King had an entire reel’s worth of action to shoot with Ketti Gallian before Tracy would be needed. Then, after a week, with Tracy still hospitalized, Sheehan announced that he was replacing him with Edmund Lowe.

Loretta Young, meanwhile, was in the hospital herself, recovering from elective surgery of an unspecified nature and getting the word out, as best she could, that she and Spence were kaput. “Speaking of TRACY,” Lloyd Pantages wrote in his column of July 5, “his romance with LORETTA YOUNG is COMPLETELY at the ‘Commander Byrd at the Pole’ stage—you know, FRIGID.” Earlier, Spence had shown up at Loretta’s hospital, flowers in hand, wobbling from room to room, and she had locked herself in the bathroom while Josie Wayne got rid of him.

The final scene in the relationship came a few weeks later, during a charity match at the Uplifters Club. Loretta attended with a party of friends, and Eddie Cantor, acting as master of ceremonies, introduced her to the crowd. Tracy was astride his horse in midfield. “At the mention of Loretta’s name,” said Jack Grant, who was present that day, “Spencer involuntarily rose in his saddle as though shot. He gazed in her direction for a long moment before he was aware that as many eyes were observing him as were looking at Loretta.” He trotted his pony off to the sidelines and made himself as inconspicuous as possible. That afternoon, it was reported, he played with particular ferocity.

Marie Galante finally got under way on July 13 with Tracy back heading the cast. Berkeley had just submitted his final version of the script, a loose compendium of everything that had come before, but Henry King still wanted a junior writer on the set, uncertain as to what Ketti Gallian could actually handle in the way of dialogue. “[S]he was not an experienced actor,” King explained. “She didn’t know how to go from one thing to another and how to create emotions.” A lengthy test King shot of her was excellent, and whatever Sheehan thought of Tracy at that particular moment in time, he felt that Ketti Gallian was potentially the biggest of stars and that she deserved the best possible support, which the forty-four-year-old Edmund Lowe decidedly was not.

Tracy felt a grudging affinity to the white-faced Gallian, who was ordered to stop using the American slang she learned from Maurice Chevalier and constantly hounded about her weight. (She was caught bingeing on chocolate bars out behind the stage, and the studio assigned a “secretary” to bird-dog her every move.) One crucial scene required her to cry, and when she told the director she couldn’t do it, King took Tracy aside and suggested that he grab her roughly by the shoulders and shake her. “Ketti Gallian had been out the night before and had had a few drinks too many,” King remembered. “She didn’t feel so great and she was supposed to be doing this scene where she was supposed to cry and beg. She said, ‘I can’t cry, I can’t cry.’ I said, ‘Spence, give her a shake. Slap her face. Get into the mood of the thing.’ Spence looked at me and I looked at her. Spence just couldn’t do it himself.”

King then caught her by the shoulders and gave her a shake and said, “Here is where you’re supposed to break down emotionally and cry and tell this man you’re sorry.” When again she said, “I can’t cry,” King slapped her hard across the face and called, “Action!” Crying and running her dialogue in a mixture of French and English, Gallian was suddenly giving the camera everything it needed. “Spence,” King urged, “play the scene, play the scene!” Tracy, who had never been witness to such a brazen piece of direction, was dumbfounded. “I never saw a man so embarrassed in my life,” King said, “[but] he finally grabbed her by the shoulders and he got warmed up to do it and the scene came off in great shape.”

Marie Galante was approximately two-thirds finished when, on Monday, August 13, Tracy again failed to report for work and was again taken off salary. According to Edmund Hartmann, the uncredited writer on the set, he turned up in New York and was returned to Hollywood on a chartered plane. “In the middle of the flight,” recalled Hartmann, “he came to and went berserk. The co-pilot had to go in with a monkey wrench and knock him out cold.” King shot around him for a week, then the picture was shut down pending his return. “Tracy came back to Fox,” said Hartmann, “but he didn’t look anything like the man in the footage we already had shot. King was a big, tough guy—but a wonderful man—and he said to Tracy, ‘You dirty, yellow son-of-a-bitch. You ruined the lives of all the people working on the picture. They’re all fired until we start up again!’ ”

Sidney Kent, who was running the Westwood and Western Avenue plants while Sheehan was away, threatened to start the picture over again with Edmund Lowe in the part of Crawbett and sue Tracy for $125,000 to cover the costs of the shutdown and all the work that had to be remade. Kent had one of his people call Neil McCarthy, Tracy’s attorney, and outline the arrangement: Tracy would pay Fox $25,000 upon resuming the picture and half his $2,000 weekly salary for the remaining seventeen weeks of the year. Further, should the studio choose to exercise the final option on his five-year contract, he would agree to a holdback of 50 percent while making the first picture of the new term, with the balance paid only upon completion of the second picture under the deal.

“I recommended to Spencer that he pay the money and go back to work,” McCarthy recalled. “I was impelled to do this largely because I felt that if we could hit his pocketbook hard, it might act as an additional strength to keep him from drinking, and particularly during a picture.” On McCarthy’s advice, Tracy capitulated and agreed to what Variety called “the most severe penalty ever imposed on a film player for holding up production.” Chastened, he resumed production the day after Labor Day looking wan and lifeless.

As her anxiety over the kidnapping threat subsided, Louise made preparations to return the children to the house on Holmby. Spence, who was making Now I’ll Tell at the time, thought that unwise, the writer of the two letters having shown an intimate knowledge of its layout and their habits there. “This was a real blow,” said Louise. “We fitted into that house so perfectly. I had hoped we would not move again until we moved into a home of our own, which I continued to believe we sometime would do. I fumed and seethed that a featherweight scamp, in concocting such a crackpot scheme, should be able to upset our whole existence.”

They found a new place on Palm Drive in Beverly Hills, a palatial spread on—for a change—flat ground with a large screened-in porch out back. For his tenth birthday, Johnny got a bicycle, something he had long wanted, and, to everyone’s surprise, he was quickly able to master the thing, even with his weak leg (which Louise feared would prevent him from ever riding it unaided). “Yes, he fell,” said Louise, “but other children fall. If he were to be like other children, he must fall sometimes.”

Occasionally, she brought him to Riviera, where she would put him on Blossom or White Sox and lead him around the yard in front of the stables. “When I mounted the horse,” John wrote, “I held the saddle tightly with both of my hands and wanted to get off. I realized I was so high and was afraid that I’d surely fall off and get hurt.” His mother insisted that he keep riding, despite his fear, and gradually he progressed to the ring near one of the polo fields, staying on entirely by balance and still tethered to the lead rope. But he never developed any real confidence on a horse—with only one leg to hold on by—until they got him a Western saddle, which made for a far more comfortable and secure ride.

He reentered Hollywood Progressive School in the fall, attending only the morning sessions (to leave time for his treatments and rest periods), but now, like other children, he was starting off for school each day at 8:30 in the morning. Primarily, he studied arithmetic and made things from clay and wood. “He had needed the companionship of hearing children,” Louise wrote, “and began to make adjustments toward life which any child learns to make at school and with other children, and which were more numerous for any handicapped child.”

Lincoln Cromwell’s first year at McGill University was similarly limited, mostly anatomy and related subjects—lectures, readings, lab dissections, the gruesome humor of students learning everything they can about the composition and workings of the human body. Dutifully, Cromwell kept up a running, if largely one-sided, correspondence with his famous sponsor, reporting on exams and study groups and distinctive members of the faculty, mixing in thumbnail sketches of the other students, accounts of the weather and boardinghouse horseplay, anything that could help portray the color, the drudgery, the genuinely hard work that went with being a medical student. “Immersed as we were in the study of anatomy,” he wrote, “it never occurred to me that any descriptions of our dissections would be offensive to Spencer. And, in fact, they were not. He was always highly interested in even the most technical aspects of the study of medicine.”

Through the turmoil of that first year—which spanned almost the full extent of the Loretta Young affair, the very public separation of the Tracys, the fights, binges, extortion letters, the mediocre pictures and the loan-outs, the arrest off Sunset, and the hopes, largely dashed, of bigger things to come—Tracy had Cromwell’s letters, bright spots in a fast life that was sometimes more than he could handle. “Glad you are getting along so well,” Carroll wrote back in October 1933. “Spencer is away on location. He got a big laugh over your letter about the stiffs. Keep us posted on all you are doing.”

In December, Cromwell heard from Dr. H. O. Dennis, the man who had originally put the two of them together. Spence had read some of his letters aloud, and Denny was pleased to be able to report that Tracy was “very well satisfied with his bargain up to this time, and that he is as proud of you as you are grateful to have him as a friend.” A couple of weeks later, Tracy himself wrote, reiterating in a fatherly tone how much he enjoyed the letters. “Have just signed a new contract [meaning his third option had been taken up at Fox] so you will have no worries as far as your continuing at McGill is concerned.” Enclosed with the letter was a check for twenty-five dollars “which I want you to use for a Christmas present for yourself.”

Cromwell came home to Los Angeles over the summer of 1934, driving a 1920 Studebaker loaded with paying passengers. A few weeks after his arrival, during the early days of filming Marie Galante, Spence invited him to dinner, which turned out to be a formal party at which he was the guest of honor. “After dinner they wanted to go out on the town, but I declined because I had to be at work at Douglas [Aircraft] early in the morning. I recall that Spencer laughed and said something like, ‘Well, he seems very conscientious so we’ll have to let him go.’ ” He saw Tracy several more times over the summer, then was horrified when he called Carroll just short of his departure and found that his benefactor had lost his job and that “everything, including me, was on hold.” The date was August 26, 1934, and it was doubtless Cromwell’s presence—one of the many responsibilities Tracy now carried—that contributed to his going back to Fox the following day and agreeing to Sidney Kent’s punitive terms for reinstatement.

“I was ready to start the second year of medical school,” Cromwell wrote, “and apparently Spencer would continue my support.”

In September Jesse Lasky asked Loretta Young to come to his office. She was making The White Parade for him at Fox, and he wanted her for his next picture as well, a tale about modern travelers stranded in a California ghost town called Helldorado. She knew the film was set to star Spencer Tracy—had been since the spring—and although she would have loved to have done it, she didn’t dare, not wanting to “start the whole thing over again.” Lasky was glad he asked, sure there was no good to come from forcing the two of them to work together again, and within a few days had signed Madge Evans for the role of Glenda Wynant, spoiled society girl. The film was set to start on Monday, September 24, but Tracy, who had been seen around town the previous couple of weeks with actress Erin O’Brien-Moore, never showed, and by noon it was obvious he wasn’t going to.

“The studio gumshoed all the bars but couldn’t find him,” Lasky said. “Postponing the scheduled starting date of a picture is sometimes prohibitively costly, if not downright impossible, because of interlocked commitments geared to a timetable. In this case, we couldn’t even shoot around our star until he showed up because he had to be in almost all the scenes. We slapped Richard Arlen into the part, which didn’t fit him at all, but there was no time to tailor it to his personality. The studio rounded up Tracy a few days later, and I sent word to him that I would never ask him what happened but that it might have happened to me instead of him and I was glad it didn’t so I was willing to forget it.”

Jack Gain prepared once again to charge Tracy for holding up production, in this case one and a half days of overhead for the idle company. On October 13, 1934, Winfield Sheehan returned to the studio and the matter was placed before him. He talked privately with Tracy and, according to Dick Mook, told him that he knew things hadn’t been easy but that he still believed in him. “Forget what’s happened,” Sheehan said grandly. “Get out of town a few weeks and pull yourself together.” Winnie Sheehan, Tracy later told Mook, was, with the exception of Louise and his own mother, “the most understanding person I have ever met.”

With a great weight suddenly lifted from his shoulders, at least momentarily, Tracy made plans to go to Hawaii for a week with Carroll. He was within a few days of sailing and unusually relaxed when he met with Gain on the subject of a new contract. “While discussing the contract,” Gain later recounted in a memo to Sidney Kent,

he informed me he wanted to make only four pictures per year—he wanted approval of stories—he wanted the right to do a picture on the outside, in addition to which he wanted much more money than I offered him, none of which were granted … In my opinion, the deal was a very good one, considering the offers that Tracy received from other studios, and I am positive that if the discussion has to be re-opened and changed so that we are compelled to make him pay the additional $6000 and keep half his salary as outlined by [studio treasurer Sidney] Towell, that he will definitely walk out on the deal, and the only thing we would have left would be to exercise our option for one year at $2500 weekly, in addition to changing his present frame of mind, which we consider is very good.

Tracy’s estrangement from Leo Morrison was a significant factor in the deal’s getting made, for it would have been considered improper for another company to have opened talks with Tracy while his contract with Fox was still in force. He likely could have doubled his weekly rate by freelancing, yet he had no clear perception of his position in the marketplace. “Spence’s naiveté,” his pal Mook once said, “runs second only to his ability as an actor.” Competition for established screen personalities was at an all-time high, the flow of new talent from the legitimate stage having slowed considerably.

Tracy returned from Honolulu sunburned but rested and went back on salary on November 5, 1934. The next day he signed a new two-year contract calling for $2,250 a week during the first year and $2,500 a week for the second. Sol Wurtzel, grinding out programmers at the Fox Western Avenue complex, had Tracy’s final assignment under the old pact: a high-concept, effects-laden spectacle built around the title Dante’s Inferno.

Wurtzel, whose commercial instincts ranged from the plebeian to the downright bizarre, had overseen a 1924 feature of the same title. What he proposed to get from a talking version was not much different from the earlier picture, an allegorical tale of damnation and redemption with a fabulous tour of the Inferno as its centerpiece. The idea was first floated back in January, the crown jewel of the seventeen pictures Wurtzel proposed to deliver that season. It was formally announced for the program in June, promising an “amazing drama” depicting the “afterlife fate of ruthless millionaires in lower regions” as envisioned by director Harry Lachman and a small army of artists and technicians.

The original outline by Philip Klein and Rose Franklin proposed a radical break from the plotline of the original film, suggesting a sort of Cavalcade of tormented souls: “The drama aims at three separate groups of people—the romance of the so-called flaming youth of today, the middle-age story of a man and wife, and the lonely strength of a financial genius. Each contributes to, and enriches, the other while the pictorial leveler of the Inferno is an integral part of the story development, rather than an illusion of abstract thought.” Wurtzel thought the storyline too fussy, and when Robert Yost, onetime head of the Fox story department, got involved, it was reduced to the rise and fall of one principal character, an itinerant carny by the name of Jim Carter. Wurtzel declared he wanted Tracy for the part of Carter, proposing once again to team him with Claire Trevor.

As a junior writer, Eric Knight, the British journalist who would come to be known as the creator of Lassie, was brought in on a story conference. Carter, Wurtzel explained, was to be a stoker on a ship. “He clouts the engineer and swims to shore and lands at a sort of Coney Island, where there’s a concession—a sort of side show—called the Inferno. He goes inside and meets the daughter of the man and they get married and have a kid. Then he gets the ambition bug. Before long, he owns the concession—then the whole island—then he builds a great big inferno sideshow on a weak pier that collapses.”

So far, so good, but then Wurtzel, Klein, and Lachman proceeded, in true Fox fashion, to bring in a current—and completely unrelated—story, the previous month’s disastrous sinking of the S.S. Morro Castle, making it the third act of the picture. Bewildered, Knight withdrew, deciding it would be better “to play Achilles and sulk in his tent” than to try and urge Wurtzel and his associates to a more coherent treatment. Dante’s Inferno entered production the week of December 3, 1934, as did Will Rogers’ Life Begins at 40, George White’s Scandals, and The Little Colonel, a musical from the makers of Bottoms Up with Fox’s newest and most commercially potent star, six-year-old Shirley Temple.

Fox, for a change, was riding high. In the space of two years, Sidney R. Kent had taken a $15 million loser and restored it to profitability, showing a net income of more than $1 million for the first six months of 1934. In gratitude, the Fox board, including the representatives of Chase Bank, the company’s biggest stockholder, tore up Kent’s old contract and awarded him a new three-year deal. Weakened in the process was Winnie Sheehan, whose rumored departure was always part of the industry grapevine. Kent and Sheehan conferred, posed for pictures, got along for the sake of the company, but Kent was onto bigger things for Fox, and none of them involved the man who was Spencer Tracy’s biggest booster.

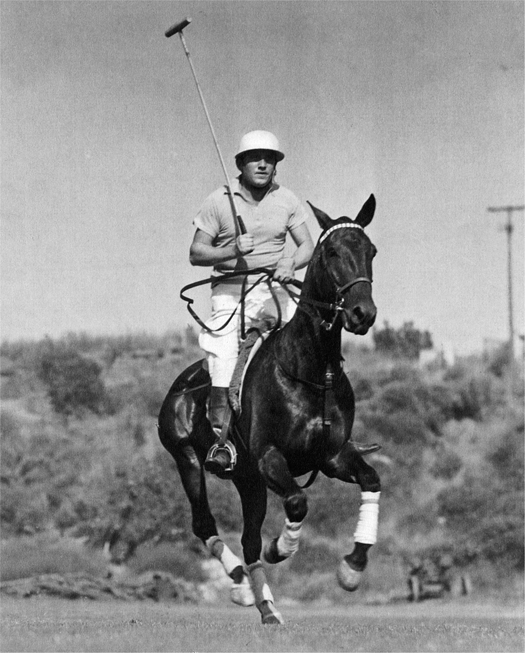

Tracy came to terms with Louise’s passion for polo and grew to admire her accomplishments on the field. (HERALD EXAMINER COLLECTION, LOS ANGELES PUBLIC LIBRARY)

Louise, meanwhile, was barnstorming across Texas with a handpicked group of eight other players, staging exhibition games to “prove to the unsuspecting public that girls’ polo can be good polo.” They stopped in Abilene, Arlington Downs, Austin, and San Antonio, playing to large crowds and consistently making front-page copy in the sports sections of the local papers. Louise throughout urged more and better opportunities for female players. “Our shots are not as long,” she acknowledged in the Abilene Morning News, “but they can be just as good shots, and the players can master the difficulties encountered in hard riding. Then, too, it is no harder on women physically than a good game of tennis singles. I’ve played both, so I should know.”

Spence was plainly fascinated by Weeze’s self-styled “missionary tour,” coming as it did on the heels of the newly organized Pacific Coast Women’s Polo Association. Within days of her return, Harrison Carroll of the Evening Herald Express ran the following item: “The Spencer Tracy reconciliation is almost complete; Spencer and his wife, guests at a dinner given in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Winthrop Aldrich (visiting banker) from New York, spent the entire evening dancing together.”

Marie Galante opened with scarcely a mention of Tracy from the New York critics, and now he found himself—for the first time in nearly a decade—generating less ink than his crusading spouse. He gave her a diamond-studded wristwatch for Christmas, was seen out on the town with her, dancing at the Beverly Wilshire and the Cocoanut Grove and talking animatedly at the Clover Club. While their reconciliation wasn’t yet a done deal, they had come to realize they were greater as a couple than the sum of their individual parts and that nothing could really dissolve all the life they had shared, all the marriage they’d experienced.

Dante’s Inferno was hardly an actor’s dream. Tracy was not keen on doing it, but could scarcely refuse given the fiscal sword of Damocles that now hung over his head. Claire Trevor was no more enthused with the material, nor with Lachman’s handling of it. “They gave him a lot of time and a lot of money,” she said, “but it was not an A-picture. Harry Lachman was a dreamer, really a creator, an artist, but crazy, you know? The picture had no boundary, no spine, no foundation. It may have been an A-movie budget, but it was a B-movie script.”

The plan originally was to shoot the carnival exteriors at Long Beach or Ocean Park, but Lachman thought the real concessions too drab to use. So an amusement pier was constructed on a stage at Western Avenue and real-life concessionaires given jobs as extras at five dollars a day. The vast set saved the inevitable delays that would otherwise have resulted from winter wind and rain, but also made it possible for Lachman to shoot round the clock, and frequently he did.

Filming crept past the first of the year and eventually encroached on the start date of another picture, a modest comedy titled It’s a Small World. Rather than delay it, the studio compelled Tracy to begin the second film while still shooting the first, splitting his time between two stages over a period of a couple of weeks. After nearly ten weeks of filming, Lachman had a perfectly serviceable melodrama, the sort of thing Fox normally turned out in eighteen to twenty-four days. Dispensing with his actors in mid-February, Lachman spent the next month—and approximately $200,000— perfecting the Inferno segment, which would occupy an entire reel of footage and employ the services of several prominent illustrators and designers, Willie Pogany and Hubert Julian Stowitts among them.

It was Stowitts, particularly, who was responsible for the conga lines of writhing bodies, oiled and muscular, stripped to within an inch of the Production Code and arrayed along tiered and cavernous pits of fire, their size due, in large part, to the masterly glass paintings of Ben Carré. Nearly naked extras were lined up and sprayed with makeup that gave them a translucent quality, while miniature figures of men were cast in plaster and suspended from a revolving disk to create the illusion of flight. Spun before the lens of a high-speed camera, they appeared to be real bodies floating in slow motion through the sulfurous air of the director’s own private Hades. The miniatures were the responsibility of Fred Sersen and his special effects crew, while the fire effects were the work of Lee Zavits, who would later be instrumental in bringing off the burning of Atlanta for Gone With the Wind. When production on Dante’s Inferno came to an end, Lachman and his crew had spent nearly $750,000 and printed an estimated 300,000 feet of film.

Tracy was sometimes dwarfed by the bizarre spectacle of Dante’s Inferno (1935). Set by unit art director David S. Hall. (SUSIE TRACY)

“I ran amuck,” Tracy admitted in the confessional of the fan magazines,

that’s all. I did all kinds of crazy things. That I have not had to pay a sterner penalty is due to the kindness of Winfield Sheehan, the head of Fox, who forgave me for not showing up on the set, and to the kindness, the extraordinary kindness of my wife, who took those blows like a thoroughbred and a sportswoman and did the thing only a superwoman can do—nothing. Louise is an extraordinary woman. That is why it is possible for me to go home again. She has never upbraided me nor berated me. She never will. She never used the things most women would use as baits to a man who needed to be reminded—she never pleaded the children nor our years together nor the “rights” that legitimately grow out of such sharing. She asked me to come home, of course, but that was all. And I have learned—my son has taught me—that there are those things in life which are stronger even than memories, than personal desires or lovely idylls.

It was December 1934, that time when he and Louise were seen almost everywhere together. He was still living at the Beverly Wilshire, but there were times at Riviera, especially on Sundays, when they were together more than they were apart. And on the days when Spence knew he would be working late, when Lachman was fussing over shots or script and taking forever to make up his mind, he would look in for breakfast and sit with Louise and the kids. “My going back had been a slow process in a way,” he told Gladys Hall in February 1935.

I’ve been unhappy for a long while, lonely, unsatisfied. Life has seemed thin and reasonless. But it sometimes takes an apparently little thing, a word, to help one make the decision. I was having breakfast last week with Mrs. Tracy and the children. I’ve never been out of touch with them, as you know. There’s never been any legal separation or anything like that.

Well, the other day, at the breakfast table, Johnny was ready for school. He wanted me to take him. I was due at the studio and couldn’t. His mother said that she would take him. And then he looked at me with a look that seemed to cut clean through all the painful business of the past months and said, “No. Girls belong with mothers. Boys belong with fathers.” I knew right then and there that nothing else mattered, not really. Not by comparison with … with this. He was right. Boys do belong with their fathers and, even more, fathers belong with their sons. And fathers have no rights that do not include their sons. I’d been thinking that I had “rights”—that I could lead my own life and all that sort of thing—but actually I foreswore that right the day that Johnny was born. I was responsible for this young life. He has a great many years ahead of him. And they are likely to be difficult years because of his handicap of not hearing. It is up to me to live those years to come with him. His place is with me. Mine is with him.

Dick Mook talked of Tracy’s naïveté, which was never more apparent than when he was around other film players. When in 1932 James Cagney told Mook that Tracy was “the finest actor on the American stage,” Tracy was nonplussed. He had met Cagney but did not know him. “Did he really say that?” Tracy asked incredulously, scarcely able to believe it. The following year, he approached Gary Cooper at a party and took his hand. “I am Spencer Tracy,” he said, “and I want to tell you how much I enjoyed your work in A Farewell to Arms.” Cooper assured him it was unnecessary to introduce himself, as he had watched Tracy’s own work with great interest.

The two men struck up an acquaintance, and when Tracy decided it was time to come home, he and Louise leased a ranch that Cooper owned on Dinsmore Avenue in Van Nuys. “We’re going to find out how we like the ranch life, how we like the Valley, and if we do, we’ll buy a place of our own there and settle down to some real homesteading. The children are going to have a real home now. We’ll have horses and dogs. I’ve already bought a horse for Johnny and a pony for small Susie. I’ll ride with Johnny. I’ll take him to school whenever I can. I’ll be there when he wants me.”

He added, “I suppose there comes a time in the life of almost every man when he wants to go hunting, big-game hunting, love-hunting, crazy-adventure hunting, some such nostalgia. I have had such a trip. And now I’ve come home again.”

In his later years Tracy maintained it was Fox Film Corporation that terminated their relationship in the spring of 1935. The details of the story, however, kept shifting. “They fired me,” he told the AP’s Bob Thomas in 1952. “Those were in the days when I was still drinking, and I got drunk now and then. But never on a picture—always between. Anyway, they worried. I was all set for a big, expensive picture. But they came to me and asked if I was going to behave. I told them, ‘That’s a heck of a way to get me to behave! If you’re worried about me, why don’t you let me go?’ That’s all they needed. I wasn’t a box office star or anything. I was out of the studio the same day.” Another version had him showing up drunk at the studio and being fired by an administrative executive, allegedly someone who lacked the authority to do such a thing. Sheehan supposedly raised hell when he found out, but Tracy, by that time, had signed with M-G-M and was completely out of reach.

The actual details are skimpy, but neither the Fox legal files nor Tracy’s own records—such as they are—support either account. Tracy did indeed sign a new contract with Fox on November 6, 1934, and Jack Gain’s memo to Sidney Kent clearly shows that no agent was in on the deal. Gain was, in fact, vigorously patting himself on the back for moving so quickly and taking advantage of Tracy’s good mood in the wake of Sheehan’s suggestion that he “get out of town.” Had he waited, Gain implied, renewing the pact would have been much more difficult, if not downright impossible. Tracy’s services were never shopped to other studios; in fact, he accepted a weekly rate $250 less than would otherwise have been due him under the terms of the old contract. Admittedly, the new pact wiped away all further obligations for the delays incurred on Marie Galante and Helldorado, but an agent would undoubtedly have driven a harder bargain for a man who was now widely regarded as one of the screen’s best actors.

A week later, an item appeared in Variety indicating that Fox had given Tracy a straight two-year deal, no options. “Old pact,” the paper noted, “was torn up.” This must have come as news to Leo Morrison, who was aware of M-G-M’s interest in his former client and had an obvious stake in repairing the relationship. Sometime after that item appeared, Morrison got back in touch with Tracy and, subsequently, the two men entered into an oral agreement whereby Morrison would collect a 5 percent commission on all monies received under the deal were he “successful in securing the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract.” Morrison, who was close to M-G-M general manager Eddie Mannix, went into action and was apparently in talks by the time Tracy began work on It’s a Small World on February 2, 1935. Five days into the film, Fox attempted to commence employment under the terms of the new contract, but Tracy, evidently acting under Morrison’s advice, never signed and returned the letters agreeing to appear.

Actress Astrid Allwyn could remember the “tremendous tension” on the set of It’s a Small World more vividly than the film itself. “There is no question in my mind that something was wrong, but I was not that sophisticated to understand the actions of other actors.” There was the pressure on Tracy to sign and return the letters activating his new contract, something Allwyn could not possibly have known. He was also shooting two very different pictures simultaneously, one requiring a long introductory sequence played entirely in the rain. Cinematographer Arthur Miller recalled that director Irving Cummings was “half loaded” on the picture, a circumstance which could not have improved his leading man’s disposition. Moreover, Tracy was in the process of moving for the sixth time in four years. The result was that he was withdrawn and quiet on the set, a considerable counterpoint to the carefree vacationing lawyer he was playing in the film.

The story itself bore a resemblance to the recent Frank Capra comedy It Happened One Night, continuing the proud Fox tradition of cranking out quick and inexpensive knockoffs of the hit pictures of other studios. The mood on the set lightened once Dante’s Inferno wrapped, but then Tracy got beaned with a dinner plate while shooting a kitchen scene with actress Wendy Barrie. The injury required five stitches over his right eye and was responsible for a week’s delay in finishing the picture. Tracy was seen at a lavish cocktail party given by Pat and Eloise O’Brien on Valentine’s Day, a two-inch bandage gracing his lower forehead. Sol Wurtzel used the hiatus to make some retakes on Dante’s Inferno, specifically a new ending in the aftermath of the ship disaster in which Tracy’s character looked perfectly natural wearing a bandage. It’s a Small World closed on March 2, 1935, and Tracy retired to the polo fields at Riviera, where he took a serious spill while practicing a few days later.

Whether it was the fall or the move or simply the stress of outmaneuvering the people at Fox, Tracy dropped from sight in early March and headed east with Hugh Tully, an ostler at Riviera. Hughie, the brother of Jim Tully, the famed author of Beggars of Life, knew horses about as well as anyone, and he convinced Tracy that the best polo stock was to be had elsewhere. “Horses out here are no good,” he said. “Better go back east—New England, upstate New York. Good horse farms.” The two men decided they’d drive back to New York and buy some horses. “They’d go off to Virginia, mosey around,” as Frank Tracy remembered it.

They’d be gone a couple of weeks. So before they left, Spence sat down with a stack of cards. Post cards. He wrote about four to his mother, four to Louise, four to Johnny, a couple to Carroll. “Today we did this, and today we did that.” He figured that he would probably not be able to handle a correspondence, and people would begin to wonder where the hell he was. So he got all these cards stamped and addressed, and he gave them to Hughie. First mistake. He said, “Hughie, every few days, mail some of these cards.” Well, Hughie got drunk and he mailed them all the same day. [Spence’s] poor mother and Louise were getting these cards, all of different dates, “Today we saw the Statue of Liberty …” It turned out to be quite a laugh, but it took a while for everybody to see the humor in the situation.

Louise caught up with him in Yuma via long distance—the postmarks having given them away—and Tracy got so agitated he began hurling dishes against the wall of his hotel room. The disturbance caused the guests in the adjacent room to alert the manager, and when the police showed up Tracy was charged with being “drunk and resisting an officer, cursing and breaking up things in a hotel room,” and summarily dragged off to jail. Spectators described a “beautiful battle” in which one cop was able to take both men down “for the count.” As Louise set out for Yuma with Audrey Caldwell’s husband, Orville, behind the wheel, Spence and Tully were on ice, but only long enough to make bail of fifteen dollars each. They were back on the road—reportedly to Nogales—by the time she arrived.

Andrew Tracy had taken to writing straighten-up letters whenever he read about his nephew’s troubles in the papers. Knowing Andrew would likely read about this incident, Spence sent a long, rambling wire to his uncle before quitting Yuma. It ran several pages and kept returning to a central theme: I LOVE YOU ANDREW. In Freeport, Andrew read the telegram with a heavy heart. “Oh, God,” he sighed, putting it down. “He’s drunk again.”

Tracy’s disappearance forced Winfield Sheehan to deny press reports that he had been pulled from the cast of The Farmer Takes a Wife, the “big, expensive picture” for which Tracy had been set. The film would pair him for the first time with Janet Gaynor, Fox’s top adult draw, and actor Henry Fonda, imported from Max Gordon’s Broadway production of the same title. It’s a Small World was previewed in Glendale on March 25, where it was found, in the words of the Reporter review, to be “so sadly lacking in story punch that it could be run backward or forward with very few able to detect the procedure.”

Sheehan may well have sensed trouble in Tracy’s relationship with the studio, for on Friday, March 29, he voluntarily took him out of The Farmer Takes a Wife, not as a disciplinary measure (as some suggested) but in the sincere belief that Spence “should rest before he begins another picture.” Sheehan had his own problems with the Fox hierarchy, as Kent was working a deal that would merge Schenck’s 20th Century with Fox and bring Darryl F. Zanuck to the studio as its new production head. According to Glendon Allvine, Fox’s former publicity chief, it was a move calculated to break Sheehan’s contract “by wounding his vanity and dignity and pride in the company he had helped create, and bringing in a man 20 years younger to replace him.”

By the end of that day, Sheehan’s troubles at Fox no longer mattered to Spencer Tracy, for Leo Morrison had finally settled a deal at M-G-M.

1 The players are numbered according to their relative positions on the field. No. 1 ranges closest to the opposing team’s goal and spearheads the attack.

2 For purposes of handicapping, polo players were rated by “goals.” A better player might be a six-goal man, a lesser player a two-goal man. Tommy Hitchcock, one of the best-known players of the 1920s and ’30s, was rated ten goals, the highest possible. Will Rogers, known more for his horsemanship than for the shots he made, was a three-goal player. Tracy was a no-goal player; the lowest possible rating was a minus two.