Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was the most structured of the major studios, a machine of an organization that not only ground out a disproportionate share of Hollywood’s prestige product but sold it with a sophistication that bordered on the supernatural. Much of what happened within its beaverboard walls was due to the philosophies and dictates of Irving Grant Thalberg, the frail production chief whose tireless cultivation of the studio’s star roster did much to establish and sustain the M-G-M brand. The slogan “More stars than there are in Heaven” was more than just an empty boast. While other organizations typically stumbled upon star material, Metro had the fewest surprises in terms of what it had to sell the public at any given moment. “Without stars,” Thalberg once said, “a company is in the position of starting over again each year.”

It was Thalberg’s doing that brought Tracy to M-G-M in the spring of 1935, but not everyone at the studio shared his enthusiasm. Of the nineteen pictures Tracy made for Fox, only Quick Millions and The Power and the Glory were truly memorable, and even those were considered flops at the box office. Tracy got by playing gangsters, vagabonds, and con men, and although he had genuinely distinguished himself as J. Aubrey Piper in The Show-Off, his reputation as a troublemaker was well known.

Metro, however, was in the midst of an initiative to pump up its player ranks, and Tracy would fill a valuable slot in the studio’s fabled stock company. In terms of genuine male stars, M-G-M had only Clark Gable and Robert Montgomery as leading men, neither of whom fell comfortably into the mugg category Tracy had so expertly occupied at Fox. William Powell was in his forties, Wallace Beery nearly fifty, Jackie Cooper just twelve. Charles Laughton was strictly a character man, and Maurice Chevalier was, well, Maurice Chevalier. Franchot Tone and the impossibly beautiful Robert Taylor were being brought along, as was Nelson Eddy, who seemingly came out of nowhere. In March alone, nine players were signed to term contracts, Reginald Owen, Edna May Oliver, Robert Benchley, and Charles Trowbridge among them. The studio wasn’t above acquiring talent that, by Thalberg’s reckoning, had been mismanaged elsewhere—the Marx Brothers and now Tracy being the most recent examples.

A memorandum of agreement between Spencer Tracy and M-G-M was signed on Tuesday, April 2, 1935. It outlined a seven-year deal, calling for five pictures a year at $25,000 a picture to start. The studio would advance $1,250 a week against each film, with the unpaid balance due at the end of production. Tracy was to receive first featured billing after the star or costar, with nobody’s name in larger type. The concluding sentence of the document confirmed that Tracy was not yet done at Fox: “We recognize the fact that this contract is binding only if Mr. Tracy secures a release from his Fox contract.” That same day a meeting took place at Fox Hills. Calls were exchanged between organizations, and the contract Tracy had signed with Fox on November 6, 1934, was terminated “by mutual consent.” Tracy verbally agreed—and M-G-M’s Benny Thau concurred—that prior to April 1, 1936, he would make one additional picture for Fox at the rate of $3,000 a week. Papers on both coasts carried the news of the move the following morning.

“It is understood that Tracy received a very flattering offer from M-G-M and was very desirous of accepting it,” Edwin Schallert wrote in the pages of the Los Angeles Times. “Winfield Sheehan kindly conceded to him and allowed him to go to the other studio.” The Hollywood Reporter added that Tracy’s new contract would take effect on his thirty-fifth birthday. “His first picture there will be Riffraff, the Frances Marion waterfront story that had the names of Gloria Swanson and Clark Gable penciled opposite it on the M-G-M assignment sheet for some time. Irving Thalberg declined to state last night whether Miss Swanson is still in line for the female lead.”

Louella Parsons bested them all when she said there was a “whisper” that Jean Harlow would be starred in Riffraff “and right away because M-G-M is eager to get more of her pictures on the market.” Thalberg was no longer in charge of production, his health having forced him to take on a lighter workload, but he was still responsible for the development and casting of seven pictures a year.

“Spencer Tracy,” Thalberg told Parsons, “will become one of M-G-M’s most valuable stars.”

The Tracys were still settling into their new home on the Cooper ranch, with its chickens, its horses, its solitary goat. Louise thought the house too big, but the expanse of land—five acres planted mostly with walnut trees—was exhilarating. “We looked at a number of pieces of property with the idea of building,” she said, “but Spencer always shied at the final jump. He blamed this on two hazards: summer heat and the distance from the studio. Luckily, we found a place to rent.”

There was a swimming pool, and John at long last learned to swim, as did Susie, who was approaching the age of three. They brought White Sox to the property, and Johnny’s riding improved as he cantered up and down the driveway by himself. On Easter Sunday they attended a polo match at Riviera. Then, in May, Spence and Louise had a “second honeymoon” in San Francisco, where Louise took the opportunity to visit the Gough School for the Deaf. When she asked if she could hire someone to come to Los Angeles for a few weeks over the summer and work with John on his voice and speech, an exploratory examination was suggested. A few weeks later she was back with her son, and after a brief interview the woman asked, “How much of a hearing loss has he?”

Louise answered that his loss was complete, but knew it was unusual for a child to be “stone” deaf. John hadn’t been tested since he was eight, and there was newer and better equipment now available. They marched him down the hall to the school’s 2A Audiometer, where they would be able to tell if he had, at age eleven, any usable hearing.

“Although I dreaded having one more nail driven into the already seemingly well-secured lid,” she said, “still, having no hope, I could suffer no real disappointment.” He was fitted with the headphones, then sat expectantly through the first part of the test. Suddenly he started, surprised, and then he went still, the unmistakable quality of listening in his wide blue eyes.

“I can hear,” he said.

Moving to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was like a shot of adrenaline for Spencer Tracy. The care with which he was handled and managed was light-years from the ineptitude he had known at Fox. “Spencer Tracy, looking like a million dollars, is reporting at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios every day,” Louella Parsons reported in mid-May. “If Irving Thalberg has his way, Spencer’s name will be electric-lighted throughout the world within the next year.” When Thalberg’s picture got delayed, Tracy was offered to other producers on the lot, specifically Lawrence Weingarten, who had an original story of high finance for him called “Plunder,” and Harry Rapf, who was developing a script from writer-director Tim Whelan titled The Murder Man.

A newspaper story, The Murder Man had been written on spec by Whelan and his collaborator, the British playwright and librettist Guy Bolton. A studio reader, who covered the material just days before Tracy’s arrival at M-G-M, thought it a “first-rate yarn, well written, cleverly constructed, full of suspense. Dialogue good and not so snappy as to get under the feet of the swift action.” There was one great flaw: the hero of the piece, a well-known reporter who covers murder investigations for a metropolitan daily, turns out to be the perpetrator of one of the murders he has written about so presciently. “If he could be made to kill the man who stole his wife instead of merely the one who stole his money, we could get away with it.”

Rapf himself was prone to sentiment and soft edges—Min and Bill, The Champ, The Sin of Madelon Claudet—so he was somewhat out of his element with a hardboiled crime melodrama. For the rewrite, he paired Whelan with a junior writer named John C. Higgins, who was working on the studio’s Crime Does Not Pay series of short subjects. With Higgins contributing dialogue, the two men gave the title character a stronger motivation. Tormented by his wife’s suicide and the reason for it, the character was recast in the image of the actor they now knew would be playing the part—a binge-drinking insomniac with a reputation for disappearing for days at a time. Tracy seemed to relish the part as a form of public confessional, a cleansing that signaled an end to his turbulent days at Fox.

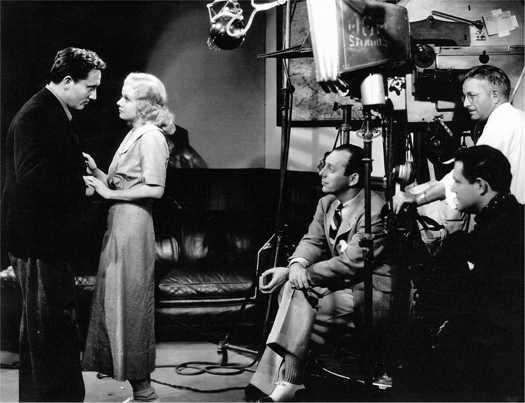

He began the picture on May 28 with Virginia Bruce, a pale blonde who had been one of the original Goldwyn girls, as his leading lady. The film was, like The Show-Off, a quickie by Metro standards, and production zipped along at a brisk pace. Shooting in Culver City was a different experience from working at Fox Hills, where the atmosphere was decidedly more administrative than creative. Sheehan’s shimmering Movietone complex was like a gigantic amusement park, expansive and contiguous. Metro, by comparison, was scattered over six separate lots, cramped and shedded and separated from one another by public thoroughfares. Exteriors at many studios were marred by airplanes and wind noise and the chirping of birds, but at M-G-M there were also Pacific Electric train whistles to contend with and the sounds of traffic just steps away.

Stages, dressing rooms, and administrative offices were concentrated on Lot 1, where the colonnade along Washington Boulevard was originally designed as frontage for the Triangle Film Corporation, so named because it was conceived as a gathering of three major producers: Thomas Ince, D. W. Griffith, and Mack Sennett. When that fragile alliance failed in 1919, the plant passed to Goldwyn, which based its production activities there until its acquisition by Marcus Loew’s Metro Pictures Corporation in 1924. Louis B. Mayer, whose own company was located on the grounds of Colonel William Selig’s former studio and zoo in East Los Angeles, came aboard to manage the newly formed company, bringing Irving Thalberg and the dour Harry Rapf with him.

With Robert Barrat and Virginia Bruce in The Murder Man, Tracy’s first assignment under his new M-G-M contract, 1935. (SUSIE TRACY)

Whelan had been a gag writer for Harold Lloyd, and he kept the action smart and sassy. He held Tracy’s first appearance until the second reel, but, unlike at Fox, where Tracy frequently appeared out of nowhere, his character dominated the early action as reporters for the Star fanned out over the city in search of Steve Gray, the paper’s famed “murder man,” missing after one of his legendary benders. In Whelan’s fanciful scenario, Gray is found aboard an all-night merry-go-round, snoozing soundly, a long string of tickets draped carelessly around his neck. As with The Show-Off, Tracy was on his best behavior, his lines down, his scenes frequently in the can with a single take. Thrown from a horse one Sunday while riding with cameraman Les White, he worked the next day as usual, nursing a back injury and a sprained arm. When a bit player failed to show for a brief exchange in a phone booth at the climax of the picture, Tracy mussed his hair and played the part himself.

It was when The Murder Man wrapped after seventeen days of filming that Tracy got a real sense of why M-G-M pictures were a cut above all the others. Where Fox would likely have shipped the film or settled at best for a few trims, Rapf ordered retakes, a new scene, and, ultimately, a completely new finish. When the picture was finally put before a preview audience on the night of July 5, 1935, it unfolded with such impact that the crowd was visibly saddened when Gray was revealed as the guilty party in the picture’s closing moments.

Tracy, said the man from Daily Variety, played the role with “quiet, compelling conviction.” A week later, The Murder Man was released nationally, finding its way to Loew’s Capitol for the week of July 26. Bolstered by a $10,000 stage show starring Lou Holtz and Belle Baker, it drew $54,000 for the week, excellent despite the common judgment that the picture itself was too modest for a deluxe house. Print critics such as Abel Green objected to Tracy’s character as “the criminal reporter type of make-believe city-roomer who dictates his stories into an Ediphone, gets pickled in the time-honored Jesse Lynch Williams tradition, and talks to and insults his managing editor in a manner no star legman ever dreamed of doing without getting the blue slip pronto.”

“Despite all this,” wrote Leo Mishkin in the Telegraph, “The Murder Man manages to be a fairly exciting piece of work. This is chiefly due, I suspect, to the acting of Brother Tracy, a man with a keen sense of values and an excellent fund of conviction. As a matter of fact, it is not too much to say that Brother Tracy is one of the finest play actors in Hollywood, and if somebody would only give him a decent story, he would emerge as a star of the first magnitude. He is real, he is convincing, and he seems to know who it’s all about. That he makes The Murder Man a plausible and believable motion picture is a mighty tribute to his prowess.”

There was still, however, the unfinished business of Tracy’s last two films for Fox. After a studio showing of Dante’s Inferno on April 16, George Wasson had persuaded Tracy to waive billing on the picture. It’s a Small World opened in Los Angeles two days later, essentially dumped by a company no longer invested in the promotion of its star. Small World didn’t make New York until June, when it graced the bottom half of a double bill at the Times, a small grind house at the edge of the Forty-second Street theater district.

The day after Murder Man closed at the Capitol, Dante’s Inferno opened down the block at the Rivoli over Sol Wurtzel’s vehement objection. (“You can’t release Dante’s Inferno in the summertime!” he told playwright S. N. “Sam” Behrman.) At first Wurtzel was proven wrong, the film shattering a five-year attendance record in the midst of a sizzling heat wave. The conclusion of the picture’s ten-minute depiction of hell brought forth a burst of applause from an opening day audience, but, with another act yet to come, it was anticlimactic, and the critical consensus was that the rest of the picture was dull. “As you may have gathered,” Douglas Churchill said in concluding his notice, “Dante’s Inferno will be greedily accepted by children and received with mixed emotion by their elders.”

It flamed out quickly, word of mouth being poor, and it was a clunk in the playoffs, where the strategy of emphasizing the Inferno sequence, with its writhing bodies and implied nudity, kept small-town audiences away. When the final tally was in, Wurtzel’s masterwork posted a loss of more than a quarter-million dollars.

Tracy had just returned from Santa Barbara, where the annual Fiesta Week was in full swing, when, on August 16, 1935, word spread through the film colony that Will Rogers had been killed in a plane crash near Point Barrow, Alaska. Tracy had been aware his pal Bill was off with aviator Wiley Post, but the true purpose of the trip—the opening of an air route between Alaska and Siberia—had not been widely known. Flags were dropped to half staff at public buildings in Beverly Hills, where Rogers had reigned as “honorary mayor” in the 1920s and where city and police officials now gathered to mourn. All municipal court cases were postponed, and the gala premiere of Rogers’ newest picture, Steamboat Round the Bend, was canceled at Grauman’s Chinese. John Ford, who directed the movie, “went to pieces,” Rogers having declined to sail with him to Hawaii so as to make the flight with Post. “You keep your duck and float on the water,” Rogers had told him. “I’ll take my eagle and fly.”

Louise hadn’t known Rogers well—he called her “Ma Tracy”—but Spence was inconsolable. They attended the simple funeral at Forest Lawn on the afternoon of the twenty-second, where only the four Cherokee Indians in attendance managed to remain stoic. Later, he gave an interview that was spun into a bylined remembrance for Picture Play magazine, recounting a time at Bill Howard’s house when Rogers came by: “We sat around talking for a while. When he rose to go, Howard urged him to have a nip while waiting for his car to be brought around. ‘I ain’t got any car.’ ‘Well, let me have mine brought around to take you home. It’s raining.’ ‘Naw. I walked over. I reckon I kin walk back.’ It was eight miles to his home, but walk he did. The last we saw of him he was ambling gayly down the path, cutting at shrubs and bushes with a stick he had picked up.”

News of Rogers’ death ignited another round of drinking on Tracy’s part, and it may well have been a subtle warning when, two days after the news broke, the studio fed an item to Louella Parsons. “Perhaps my sense of humor is distorted,” she wrote, “but somehow when they told me at M-G-M that Spencer Tracy would be making a costume picture, I had to smile. I just couldn’t picture the virile Spence doing a hand-kissing act. But this picture, I am assured, is going to be different.” Parsons went on to report that Tracy was to star in an original story about an Irish captain of the Grenadiers, the action for which would take place in England, France, Italy, and Germany. The title? Tosspot…which was—and still is, of course—another word for “drunkard.”

Riffraff had been developed specifically for Jean Harlow. “The studio doesn’t think so,” Thalberg said, “but I think she needs a crack at a dramatic story, and this is it.” The actress donned a red wig for the part of Hattie, a feisty cannery worker who’s stuck on Dutch, the cocky leader of the tuna fishermen and their union. It was a thankless role for Tracy, and Judith Wood, playing Harlow’s friend Mabel, remembered the picture was held several days owing to his “illness.” She went over to him when he finally appeared, having known him from Looking for Trouble (the eventual title of Trouble Shooter): “I said, ‘I’m sorry you were sick, Spencer,’ and he said, ‘Sick! Hell, I was drunk.’ ”

The picture began shooting on August 29, its script having been given a final polish by Anita Loos, who took screen credit along with H. W. Hanemann and Frances Marion. Tracy kept to himself, and associate producer David Lewis, who was present throughout the course of production, never got to know him. Harlow, who wasn’t drinking herself at the time, could see that Tracy was and resented it bitterly. One day, she stalked off the set and makeup artist Layne Britton followed. “What’s wrong, Baby?” he asked. “Tracy’s gassed,” she replied, “and I’m not going to work ’til he gets straightened out.”

Tracy was developing a reputation for being testy, and he gave unit publicist Cecil “Teet” Carle more “static, more worries, frets, resentments, frustrations, and ulcer symptoms” than any other performer. “A press agent welcomes consistency. A 100% heel or bitch can be coped with because he never varies. But Spence could be snarly and nasty one day, palsy and helpful the next.”

Publicist Eddie Lawrence had his first encounter with Tracy when assigned to write the pressbook for the picture. Tracy was in his dressing room with the door closed. Lawrence knocked, and Tracy “wiped me out. He said, ‘Don’t you ever, EVER knock on my door when the door is closed!’ And I said [in a crushed voice], ‘Oh.’ And so I went to see [M-G-M’s advertising director] Frank [Whitbeck]. And I said, ‘Frank, what’s this with Spencer?’ He said, ‘Well, you know, he has this terrible insomnia, and he’s resting.’ So it was quite understandable. Spence would leave the studio and go get a rubdown and sleep on it.”

Filming Riffraff with Jean Harlow. Director J. Walter Ruben looks on, 1935. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Riffraff was a major undertaking, much of it shot on M-G-M’s Lot 1, where an elaborate wharf had been constructed alongside a man-made lake. The exteriors and the scenes shot on location at San Pedro gave the film size, but also made for an exceptionally long shoot. A total of fifty-six days was spent filming an unexceptional movie that did nothing to enhance the Thalberg legend nor advance Tracy’s standing with audiences.

They were a happy pair, Johnny and his mother. They learned in San Francisco that he had some hearing—not much, but some. “I can hear,” John proudly announced to just about everyone, confident that he would soon be hearing as well as everyone else. “We could not bring ourselves to disabuse his mind of this completely,” Louise said, “and, after all, how did we know, anyway?”

What hearing he had was in the speech range, which suggested the possibility that with the right hearing aid he might acquire a more natural tone of talking and the necessary adjuncts—rhythm, accent, inflection. As soon as possible, he was given an audiometric test at the Western Electric office in Los Angeles. The technician was not able to give them an audiogram, a detailed chart, but thought John had about 15 percent usable hearing and recommended the company’s most powerful instrument, a large air-conduction aid of the type used in schools. He was sorry, the man said, but the company didn’t let their machines go out on trial. “Of course,” said Louise, “we bought his machine.”

A woman from the Gough School came to Van Nuys for a month over the summer of 1935 and worked with Johnny for three hours a day. At the end of summer, just as Spence was beginning work on Riffraff, she said that she was sure he heard enough to make residual training worthwhile. He had worked hard, and his speech showed considerable improvement. Louise, however, was not convinced the psychological effect had been good.

In the first place, John started out—perhaps we all did—with too much optimism. But, of course, we adults had understood the limitations both of John’s hearing and of the instrument, and were experienced in disappointments. John had confidently expected the impossible. He was too young to appreciate the amount of intense and protracted work necessary to gain small results, although I do believe that the long uphill struggle with his leg, and his great patience and cooperation there, had given him an insight and philosophy beyond his years. Still, I am sure the labor must have seemed to him out of all proportion to any apparent gain, and his disappointment, as week followed week and no great change in his hearing took place, must have been keen.

It was a case of overdoing a good thing, and the whole experience, with all its attendant anxieties, left him apathetic and rebellious and unwilling to continue with even the short daily periods his mother attempted into the fall. When Johnny’s tutor came back into the picture, she would have none of the hearing aid and consigned it to the closet. She said it was too much to fuss with in the scant ninety minutes they had together each day, and that John had too little hearing to make any work with a hearing aid worthwhile. When Johnny wrote his autobiography in 1946, he made no mention of it.

By September they knew that they liked the San Fernando Valley, its open spaces, its solitude, its decidedly rural way of life. However hot the days were, the nights were cool enough for blankets. “We also knew,” said Louise, “we wanted a home with more ‘outside’ than ‘inside,’ call it a ranch, farm, or just ‘place.’ ” Spence, now faced with a thirty-mile drive to the studio, stayed at the Beverly Wilshire during the week, coming home to Van Nuys on Sundays or whenever he wasn’t shooting a picture in Culver City. They planted a vegetable garden, added three dogs (including a mate for Pat named Queenie), more chickens, and a thoroughbred mare in foal. Casually, they also began looking for property to buy.

Having worked in support to Jean Harlow for two solid months, Tracy was now returned to Harry Rapf for a picture called Whipsaw. Again he was cast in support of a big name, Myrna Loy, who had made a terrific hit as Nora Charles opposite William Powell in The Thin Man. After being paired again with Powell in a second picture and then loaned very profitably to both Columbia and Paramount, Loy fled to Europe, feeling exploited and unwilling to return until her compensation had been brought into line with that of her costar. The ensuing standoff took almost a year to resolve; when Loy returned to M-G-M in September 1935, she had been offscreen for nine months.

Whipsaw was a caper movie, based on a story by James Edward Grant that had appeared in Liberty magazine. Loy was an international jewel thief, Tracy the undercover G-man trying to win her confidence. The script was all thrust and parry, the kind of dialogue at which Loy had proven so adept in her pictures with Powell. Tracy lacked Powell’s elegance—the picture was first conceived with Powell in mind—but made up for it with an earthiness that played surprisingly well against Loy’s composure and poise. Despite their initial dustup over his drinking—perfectly justified, he later acknowledged—Tracy had grown immensely fond of Jean Harlow during the making of Riffraff and found Loy, in comparison, somewhat aloof. “[S]he had me scared,” Tracy admitted. “I didn’t know how she’d feel about [working with me]. And what worried me the most was kissing her.”

Loy was on her way to becoming a big star, and Tracy covered his nervousness with banter. “He’d keep contrasting me to Jean, telling me what a good sport she was, what a prima donna I was, and how her Victrola had cheered them up on the set,” the actress said in her autobiography. “In self-defense, I finally took the hint. That began his long torch-carrying: I was running and Spence was running after me. He would go out to [Riviera] and call my friend [and stand-in] Shirley Hughes to find out where I was. ‘What difference does it make?’ Shirley told him. ‘She isn’t going to see you.’ Which I never did. I liked him, but not enough.”

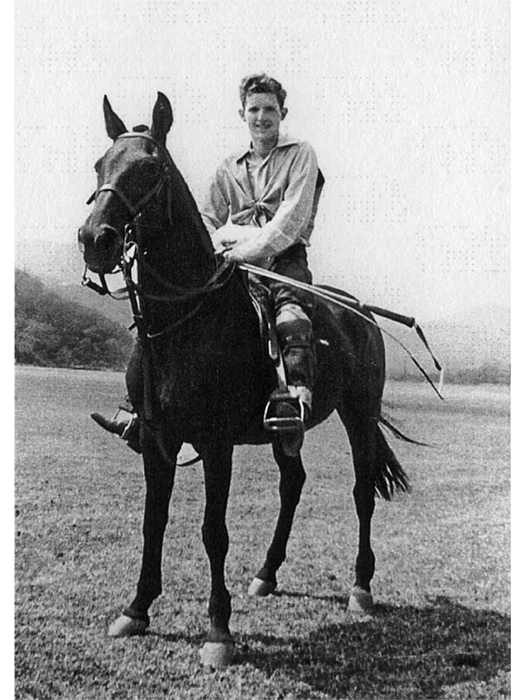

They completed Whipsaw in twenty-six days, and Tracy went back to polo, from which he had refrained during the course of production. Over the summer, Johnny had started to ride in the gymkhanas held every month at Riviera, entering the trotting and potato races, the flag relays, and the autograph races that required the participants to dismount and sign their names before remounting and galloping off toward the finishing line. He was watching the last chukker of a mixed game on Thanksgiving Day when his father rode up and told him to get out on the field and play. “I was very much surprised, as it seemed to me all of a sudden. I rode nervously onto the field and only trotted along with the players. Finally, about the middle of the chukker, I hit a ball two or three times for the first time while walking. Obviously, other players waited generously and let me do the job. I was very much excited and felt proud.”

Tracy’s contract with Metro required him to make one radio appearance in support of each film he did for the studio, and his first came up on November 29 when he and Harlow performed scenes from Riffraff on Louella Parsons’ Hollywood Hotel. It was a national hookup, unusual for the time, as most network shows originated in either Chicago or New York City. Parsons used her muscle as columnist for the Hearst syndicate to get the industry’s biggest stars to appear for little more in compensation than a case of Campbell’s soup. The exposure was usually worth it, but for some film personalities the cost came in the terror of broadcasting live for an audience of some 20 million listeners. Tracy, for one, disliked the experience, but it wasn’t what sent him off on another bender in the days that followed.

In the eighteen months since Loretta Young ended their relationship, she had starred or costarred in five motion pictures, including The Crusades for Cecil B. DeMille. Prior to making the DeMille picture she had gone on location to Mount Baker, Washington, for a film adaptation of the famed Jack London novel Call of the Wild. It was a rugged shoot, made all the more so by the volatile mix of personalities at its core. Jack Oakie was in the cast, as boisterous as he was on Looking for Trouble, and directing it, as he had that aforementioned film, was William A. Wellman. Something of a coup for 20th Century was Young’s leading man—Clark Gable, borrowed from M-G-M. Then, of course, there was the flirtatious, semivirginal Loretta herself, now all of twenty-two years old.

Gable was married to a wealthy Houston socialite seventeen years his senior. (It was a “step-up” marriage, as his first wife—his acting coach—put it.) Ria Gable, a matronly fifty-one, was the lingering wife of Hollywood’s biggest male star (and one of its most notorious cocksmen). With an Academy Award looming in his immediate future, Gable had already decided to seek a divorce when he left for Bellingham with Wellman’s company in January 1935. Immediately, he fixed Loretta in his crosshairs, and the blizzard conditions on location only worked to his advantage. Once they began filming, she entered that dreamy zone she almost always occupied when acting opposite a man of just about any description. Gable had an animal-like quality, sexual and dangerous, and she began to regard him romantically. “I think every woman he ever met was in love with him,” she said.

John Tracy on the field at Riviera, circa 1935. (SUSIE TRACY)

Gable’s pursuit of her became an all-consuming goal that bordered on an obsession, and Wellman was so annoyed with his behavior, slowing progress on the picture as it did, that he made a very public issue of it. “I called him for it,” Wellman said, “which I shouldn’t have done in front of my company.” Sometime during the making of the picture, Gable made his move and Loretta soon discovered that she was pregnant. After finishing a role in a minor film called Shanghai, she fled to Europe in the company of her mother. It wasn’t unusual for an unmarried actress to hide a pregnancy, but it was uncommon to carry one to term and remain unmarried. The common remedy—abortion—wasn’t an option for a practicing Catholic, and revealing the father as a married man would have amounted to professional suicide. Upon her return, the actress went into seclusion, illness and fatigue the official reasons.

There was, of course, a lot of talk, and it quickly got through to Tracy that for all the bum publicity he had endured over the course of their ten-month relationship, it was Gable, completely unfettered by Catholic chivalry, who had gotten her into the kip. He called and went to see her, her condition now more or less an open secret. Word of the baby’s birth on November 6, 1935, spread like wildfire. With Whipsaw in the can, Tracy was seen out on the town, sometimes with Louise but usually stag, most often at Billy Wilkerson’s Cafe Trocadero on the Sunset Strip. The food was expensive and not very good, but it was a handy hangout for a good many stars, much like a private club, and he could always count on seeing somebody he knew.

Tracy frequented comedian Frank Fay’s Sunday night programs there and could be seen in wire photos greeting thirteen-year-old Judy Garland after her appearance as one of Fay’s “undiscovered stars.” When John Barrymore emerged from seclusion after fleeing nineteen-year-old Elaine Barrie, it was in Tracy’s company at the Troc. And it was at Wilkerson’s place on a Tuesday night in early December 1935 where Tracy overheard a reference to Loretta and a “baby with big ears” and shot to his feet. “Who said that?” he demanded and turned to find Wellman, on whose watch Gable’s conquest had occurred.

Dottie Wellman was upstairs at the time and heard about the remark her husband made only after the two men had been separated. “He shouldn’t have said that,” she acknowledged. “Bill had a chip on his shoulder, especially when he was drinking.” Tracy delivered a punch to Wellman’s ribs, which the director countered, according to news reports, with a left to the ear. “He and I just didn’t like each other,” Wellman later said of Tracy. “We had a lot of fistfights, and I always beat him because he’d start talking and I didn’t talk.”1

Mutual friends interceded, and those two punches were the only ones landed that night. By the time their altercation made the papers, they were both minimizing the incident, seemingly bewildered by all the commotion. “We had a little misunderstanding, and the others in the place seem to have made quite a fight out of it,” Tracy innocently told the Examiner. “There were no hard feelings, and we’ve laughed about it since.” Added Wellman, laying it on a bit thick: “We’ve been friends a long, long time and made a couple of pictures together. It was merely a case of misunderstanding which has all been straightened out, and I can’t for the life of me understand why so much fuss is being made about it.”

Neither would confirm the name of the actress involved, but the story made the wire services and at least one of the New York dailies ran both her name and photo alongside Tracy’s and capped them with the headline FAIR LORETTA’S KNIGHT. As columnist Jimmy Starr wrote the next day, “The beaut that caused the fistic row between Bill Wellman and Spencer Tracy is certainly getting more than her share of nasty talk. Why doesn’t Hollywood leave her alone?”

Whipsaw, released on December 6, was sold almost entirely on the strength of Myrna Loy’s return to the screen. It took a dive in New York, but did better elsewhere, pulling in nearly $1 million in rentals on an investment of $238,000. By pairing him first with Loy, then with Harlow—Riffraff hadn’t yet been released—Metro was getting audiences used to seeing Tracy with top-tier female stars. The next step would be to put their top male stars alongside him—Gable, Powell, and maybe Beery as well. It was a strategy Tracy could appreciate, one that Fox never could have embarked upon, even had it occurred to somebody to try. For Christmas, everyone in the extended family got a card from Spence and a check for fifty dollars, the studio’s return address and Carroll’s careful handwriting on the envelope. (“Fifty dollars in the 1930s was a helluva Christmas,” said Frank Tracy.) Louise made a pitch of her own for a gift when she suggested that Spence give up drinking altogether. “I just think it would be better for you all around, don’t you?”

And so, on December 20, 1935, Tracy took the pledge and declared himself on the wagon.

Norman Krasna was a hot commodity, a balding twenty-five-year-old at work on a slick comedy for Clark Gable when an article in the Nation gave him an idea for a play. There had been a lynching in San Jose following the kidnapping of a department store heiress, and Krasna began to wonder what would have happened if the men they hanged had been innocent. “I told my idea to [M-G-M story editor] Sam Marx and [producer] Joe Mankiewicz. They were crazy about it.”

Sometime later, after Krasna had left M-G-M, Mankiewicz told the story to Louis B. Mayer. Mayer found the subject distasteful but told Mankiewicz, who had exactly one picture to his credit, that he could do it anyway. “I’m going to let you make this film, young man, and I’m going to spend as much money advertising this picture as Irving Thalberg spends on Romeo and Juliet. Otherwise, if it fails, you’ll always say we didn’t get behind it properly. This way, I’m going to prove to you that this picture won’t make a nickel. Now go make it!”

When they phoned Krasna in New York to purchase the story, he said he had pretty much forgotten it. “I had to dictate it as he’d told it to me,” Mankiewicz said, “so that he could sell it to M-G-M.” The two pages that bagged Krasna a $15,000 payday told the story of Joe Wilson, a young lawyer on his honeymoon in California’s Imperial Valley. A sheriff’s assistant throws him in jail on the day a kidnapping has taken place. The men of the town decide to lynch the alleged perpetrator and a mob forms around the jail. Word reaches the governor, who dispatches a troop of militia to guard the jail. Unable to get to the prisoner, the angry townspeople set fire to the building instead, burning it to the ground. “The gimmick, the hook, the invention, the inspiration,” said Krasna, “is that he is still alive.” When Joe appears to witness the hangings of the vigilantes who left him for dead, the district attorney stops the executions in the nick of time. As Joe sinks into a chair, he buries his head in his hands and says, “But they killed my dog—didn’t they?”

Mankiewicz already had the ideal director for Krasna’s story in the person of Fritz Lang. David O. Selznick, Mayer’s son-in-law, had brought Lang to the studio in 1934. Selznick put him on a project called The Journey and paired him with a writer named Oliver H. P. Garrett, but nothing ever came of it. As a screenwriter, Mankiewicz had been assigned to work with Lang because he could speak German.

“I went over and talked to Fritz a couple of times, and I found it very difficult to work with him because he had his office all rigged up as though it was a German office at UFA. He had drawings—what they call a storyboard today—all around the walls. He was working on a version of an old film he made in Germany called Dr. Mabuse. He wanted to make an American version which would involve a crooked district attorney. I got very confused, because I just didn’t see stories that way. I wanted to know the characters in the film before we started picking camera angles.”

Selznick left the studio to form his own company, and Mankiewicz told the front office he wanted Lang as the director of Mob Rule. In America, Lang’s reputation was based largely on his brilliant 1931 production of M, the story of a man hunted down as a murderer of children. He drew the assignment to direct Mob Rule about the same time Tracy encountered Mankiewicz for the first time at the M-G-M commissary.

About to start Riffraff, Tracy heard the story in much the same way L. B. Mayer had, but his reaction was much different: “I remember playing The Baby Cyclone in Boston the night Sacco and Vanzetti were electrocuted,” he later said. “The execution was to take place at midnight, and when I got out of the theater at eleven o’clock, the Boston Common was filled with people protesting the execution. The undercurrent of violence was frightening. It’s easy to see, after watching a thing like that, how mob hysteria can whip up riots or lynchings.”

Lang and screenwriter Leonard Praskins began work on a script by looking at the story from three different perspectives: the wife (“a typical American girl, married to a man in a very good social position”), the mob (“people in a small town—blacksmiths, gas station men, tailors, uneducated people”), and the man through whose character they decided all three of the stories could most effectively be told.

“Spencer Tracy,” wrote Lang,

is a lawyer, a very idealistic type of man who believes that the man is good, that crime is only a disease, that criminals are unhappy people and that the law is there to help them. He is an idealist, an optimist … When this lynching occurs to him his philosophy breaks down … This man must be made in black and white, not in color hues. Short scenes can give us this man’s character. Need no long dialogue scenes … I think his guilt is that this man who always believed that he was an idealist tries to do something for personal revenge. He does not try to understand how everything happened. He does not try to understand what drove these people to this uprising. He now has only one idea. He suffered unbelievably. He wants revenge. This is his guilt.

One of the more memorable characters on the M-G-M lot was a former title writer and gag man named Robert E. “Bob” Hopkins. “Hoppy,” as he was known to just about everyone, was the closest thing to a handyman they had when it came to a script, and when he wasn’t on a set somewhere, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, he was lurking in the studio commissary or standing on the corner—“the crossroads” they called it—ready to nab a producer and shout an idea at him. Tall and profane, Hoppy was easy to laugh off, but the words that shot out of him sometimes amounted to story gold if anyone bothered to pay attention.2

“I was walking along the street one day on the lot,” recalled Jeanette MacDonald,

and he yelled across, “Hey Jeanette, I’ve got a hell of an idea for you and Clark Gable.” He came rushing over to me. I said, “Oh you have? What is it?” So we stood there and he talked to me and told me this wonderful idea he had. I must confess it was exciting. But he said, “You know I can’t get to first base with the g.d. thing.” I said, “What do you mean, Bob?” He said, “Well, I’m getting the run-around. I try to see Eddie Mannix and he’s too busy, I’ve tried to see Thalberg and he’s too busy. I’ve just tried to see everybody and nobody wants to see me. Look, I think you could do something with it. They all like you up there. You go up and tell them you like the idea.”

Hoppy’s idea had size and punch. According to Gottfried Reinhardt, son of Max Reinhardt and new to the studio, it consisted of just six words: “ ‘San Francisco—earthquake—atheist becomes religious.’ That was his idea.”

MacDonald went to Mannix. “You see, at this point I was going pretty strong at Metro, having just done Naughty Marietta and Merry Widow, which surprised them all. Mannix said, ‘Would you like to do it?’ I said, ‘Yes I would like to do it, providing we get a decent script out of it.’ ”

The earliest bit of extant writing on San Francisco is a draft of the opening sequence by Herman Mankiewicz, Joe’s elder brother, dated January 9, 1935. The full screenplay, however, was the work of Anita Loos, the tiny novelist and screenwriter who, like Hopkins, had spent her childhood in San Francisco. According to her, the character she and Hopkins envisioned for Gable was based on the late playwright and scam artist Wilson Mizner, who had once run a gambling house on Long Island. Sometime in April, Loos’ progress on the script was halted, presumably when Gable said he would not do the picture.

“I was all for San Francisco,” MacDonald said,

because I felt like the mother of it in a way. Since Hoppy had said, “This is a picture for you and Gable,” I was stuck with this, this idea had clung to me, and then I found out that Mr. Gable didn’t want to do it. The story that came to me from Mr. Mannix was, “Who wants to sit there with egg on his face while she sings? Nobody can do anything while she’s singing.” (He may not have used that expression then but that’s what he meant.) That was primarily his reason for not wanting to be in San Francisco.

So they started to mention this one and that one and I kept saying, “No, no, no. It’s for Gable and me and I’ll wait.” They said, “What do you mean you’ll wait? Gable has another commitment. He says he doesn’t want to do it anyway.” “Will he do it after his other commitment?” “Well, yes, he has to. He doesn’t have it in his contract that he can sit back and say no.” I said, “All right, I’ll wait until this other commitment is finished.”

You see, my contract called for so much a picture. I wasn’t on a long-term contract but on a picture-to-picture basis. So many pictures and each picture was a certain price and the price rose with each picture, plus a guarantee of so many weeks. After that, I got prorated money if it ran overtime. So when I found I would have to wait another six months in order to do a whole picture, contractually and financially they said, “Either we do it or we don’t do it, and how are we going to get around it?” I said, “I’ll wait” and they said, “What are you going to do about the pay?” I said, “I’ll just forfeit the pay. Just let it go, and I’ll sit out the six months that I should be paid for because I want Gable that badly. I think Gable is right for it.” Then some stupid person told Gable that I had said I would wait and that I had said I wanted him for my picture. He said, “Her picture??” You see? Immediately he was rubbed the wrong way.

Work on the script resumed in the fall, when the film was assigned to producer Bernard H. Hyman, a Thalberg protégé, and W. S. “Woody” Van Dyke, the director of MacDonald’s two previous movies for the studio. (“We just seemed to think alike,” MacDonald said of Van Dyke.) The genial Hyman initiated a series of story conferences with Hopkins, Loos, her husband John Emerson, and Van Dyke, working not so much on developing the relationship between Gable’s character, Blackie Norton, and MacDonald’s Mary Blake, a prim country preacher’s daughter, but rather the more shaded and complex story of Blackie, the Barbary Coast gambler, and his childhood friend, Father Tim Mullin. It would be Mullin’s job, with the help of the 1906 quake, to open up Blackie’s spiritual side, and it had to be credible—couldn’t be sappy. Quickly, they got down to business: Blackie and Tim clashing over Blackie’s exploitation of Mary, Blackie’s frantic search for Mary before the hall is dynamited, Blackie thanking God when he finds she’s okay. It was, as Loos later described it, “unadulterated soap opera,” and the proper casting of the priest became the key to making it work.

Typically, priests in movies were played by character men—Edward Arnold in The White Sister, Leo Carrillo in Manhattan Melodrama, Walter Connolly in Father Brown, Detective. Casting a lead actor as the priest in San Francisco would be a bold move, giving the conflict over Mary a sizzling undercurrent of sexual tension. When the idea of playing Father Mullin was first broached to Spencer Tracy (who was anticipating Mob Rule as his next picture), he was, as Louise put it, “a little dubious about doing a priest.” Not only did he feel a terrific sense of responsibility in representing the church to a mass audience, but there was also a hesitancy that grew from his own conviction that maybe he should never have become an actor in the first place. It was a thing he almost never spoke of, but Pat O’Brien heard him say it on more than one occasion, and he repeated it once to Shakespearean scholar and author John McCabe.

“What was it, do you figure, Pat, that made Tracy such an unhappy man?” McCabe asked O’Brien one night over drinks at the Lambs Club. “It’s a real mystery, isn’t it?”

“No, it’s not,” O’Brien replied. “At least three times Spence told me why it was.” According to Pat, Tracy had never lost the deeply held nostalgia many Irish Catholic boys felt for the idea of being a priest, like one of the bright, enviable Jesuits from their prep school days. “Each time he told me he was pretty much in the bag, but he was telling the truth. I can remember once when he was looking out over the ocean, nuzzling a bottle, when he told me this. His unhappiness—he said—was that always deep down he had the feeling that perhaps he had spurned his real vocation—to the priesthood.”

As Tracy once explained it, “I was seventeen, maybe sixteen, and I was going to a Jesuit school—Marquette Academy. And you know how it is in a place like that—the influence is strong, very strong, intoxicating. The priests are all such superior men—heroes. You want to be like them—we all did. Every guy in the school probably thought some—more or less—about trying for the cloth.”

Had there, in fact, once been a calling? And was he now being asked to act a role he had spurned in real life? “I was awful scared of playing a priest,” he later acknowledged in an interview. “Sure, I couldn’t see myself in that part—or other people accepting me. I was afraid people would get mad at me for trying to play something like that.” To Van Dyke he put it more bluntly: “I’m a Roman Catholic and you know the thing that happened not long ago [meaning the affair with Loretta Young]. I wouldn’t have the crust to play a priest.” It was Van Dyke, he said, who talked him into it, who told him that he’d make him “eat” those words. “I honestly didn’t think I ought to try it. I said I’d go ahead if I had to, but I didn’t like the idea one bit.”

On January 24, 1936, the decision was announced by Edwin Schallert in the pages of the Los Angeles Times: “Instead of two stars of the first magnitude, San Francisco, [a] depiction of the old days in the great west coast city, is to have three luminaries. As is known, Clark Gable and Jeanette MacDonald for some time have been assigned to this cast, and yesterday Spencer Tracy was added … Start of San Francisco is programmed as soon as Gable returns from Mexico, which will be in about a week. Gable and Miss MacDonald have never previously appeared in a picture together, and casting Tracy with the stars is also an innovation.”

Tracy had known Gable since 1929, when he replaced him in the troubled play that came to be known as Conflict. The following year, Gable was offered the role of Killer Mears in the West Coast production of The Last Mile. The offer had come from the husband-wife producing team of Louis MacLoon and Lillian Albertson, for whom Gable had worked off and on since 1925. Albertson caught Gable in New York, where he had just closed in a play at the Eltinge Theatre. Tracy was rounding up guards and executing hostages next door at the Harris, but Gable hadn’t yet seen him.

“Here we were,” said Gable, “working alongside each other, and I couldn’t see his play and he couldn’t see mine—while mine lasted—because we worked the same hours, matinees included.” Gable and his wife caught The Last Mile: “I watched Spence as Killer Mears for two acts, and I said to myself, ‘That’s for me.’ I rushed out and wired the producer I was taking the midnight train.”

Gable impressed playgoers at the Majestic Theatre in Los Angeles, where The Last Mile had a brief but notable run. John Wexley thought him better in the part of Mears than Tracy (“less self-conscious, more dynamic”) and director William Wyler shot a test of him for Universal. By the end of the year, Gable was under contract to M-G-M, while Tracy was similarly committed to Fox. “Hollywood didn’t have any Lambs Club where we could bump into each other,” Gable said, “but both of us went out more in those days. Every now and then we’d meet at some night club or some party and we’d sit around and take the picture business apart.” The two men also occasionally saw each other at Riviera, where Gable briefly tried polo and was, in Tracy’s early judgment, pretty good.

They began shooting San Francisco on Valentine’s Day, 1936, Gable reeking of garlic in a rousing show of contempt for his leading lady. (“Gable is a mess!” she complained to her manager Bob Ritchie. “I’ve never been more disappointed in anyone in my life.”) Tracy did his first work as Father Mullin the following day and surprised some members of the crew with his level of professionalism. “I’d heard all the stories about him at Fox, that he’d go off on drinking sprees,” said Joe Newman, Van Dyke’s assistant director on the picture. “He didn’t on San Francisco; he was fine. He was always on time. He was perfect in his lines. Everything I’d heard about him, he erased.”

Clad in black cassock and biretta, Tracy played a brief phone exchange with Gable, then presided over a nighttime organ recital at the rescue mission. MacDonald sang “The Holy City” (“Jerusalem, Jerusalem”), then took part in an expository scene in which Tracy provided the backstory on Blackie Norton, “the most Godless, scoffing and unbelieving soul in all San Francisco,” and a little on himself as well. “Blackie and I were kids together—born and brought up on the Coast. We used to sell newspapers in the joints along Pacific Street. Blackie was the leader of all the kids in the neighborhood, and I was his pal.” He tells her he’s tried to do something with Blackie for years, but that “maybe I’m not the right one.”

It was one of the most critical movie scenes Tracy had ever played, and he played it as he played all scenes, with simplicity and honesty and a conviction that he was the character in all its natural shadings. The authority he exuded was unalloyed with theatrical tricks or the calculations of a leading man suddenly beyond his depth. If he had any fear, it was the fear of artificiality, the fear that lifelong Catholics would look at Father Tim and see a movie star pretending to be a priest and not the soul of a real priest, with a hardscrabble childhood in his background and wisdom as to the ways of the Barbary Coast.

There was an effort to load Tracy’s principal scenes toward the front of the schedule, as the start of Mob Rule was looming and no one knew quite what to expect of Fritz Lang. There was tension between Gable and Van Dyke, Gable and the front office. “I like Tracy very much,” MacDonald wrote after two weeks on the picture. “There’s as much difference between the two as day from nite. Gable acts as tho’ he were really too bored to play the scenes with me. Typical ham.”

Mob Rule went into production just six days after San Francisco, destined to be as grueling a shoot as Tracy had ever endured. (“2 months on wagon,” he noted in his datebook.) Lang, meticulous in his preparation, had taken nearly six months to get the script into shape, and by the starting date had storyboarded the entire film. The girl in the story was Sylvia Sidney, a first-rate actress who had heard about Lang making his American film debut and took a substantial cut in price to be part of it. She respected and admired his work, she said, and thought it important to work for him, to “back him up” after his escape from the Nazis.

San Francisco was a big, boisterous carnival of a film, festooned with balloons and good cheer and enveloped in the kind of candy apple coating that was emblematic of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer school of moviemaking. Mob Rule, on the other hand, was anything but. Grim and Teutonic, it had none of the high spirits for which the studio was typically known, and Tracy found himself stepping from Father Tim’s chapel office, brewing coffee for the chaste Mary Blake, to the opening shots of Mob Rule, in which he and Sidney portrayed all the lust and frustration an engaged couple could possibly feel in the hours prior to a long separation. Joe can’t keep his eyes off Katherine and she can’t keep her hands off him. They munch peanuts, coo words of love, and when they’re separated by the window of a Pullman car they press the glass as if electricity were passing between them. Sam Katz, the Chicago theater executive who was Mankiewicz’s titular boss, sensed the carnal energy of the rushes and sent Lang a note: “I saw your first day’s work and I am delighted. I am leaving today on a trip for about two weeks and I am sorry I will not be here with you during this period. However, I know you are going to give us a great picture.”

Tracy was used to making one take, two at the most, and was completely unaccustomed to the multiple takes Lang routinely insisted upon. One of the ways the local sheriff puts his suspect at ease early in the film is by noting the character’s fondness for peanuts. (“Some peanuts?” actor Edward Ellis asks during the interrogation scene, casually setting a bowl of salted nuts in front of him.) Tracy had done take after take, accepting a handful of nuts and tossing them into his mouth. “Well, now you’re talking my language, Sheriff. I’ve—.” And the line was aborted with an explosive cough.

“Cut,” said Lang impassively. “Bring this peanut addict a glass of water, somebody.”

Tracy’s face reddened as he spat out the chewed remains. “This guy,” he said, indicating Lang, “is trying to kill me with salted peanuts—a new variety of murder. So far, I’ve had to eat fourteen bags in succession.”

“Uh, no, Spence,” corrected the prop man. “Only thirteen.”

After quietly printing what he wanted, Lang kept it up, torturing Tracy until Sylvia Sidney signaled him that the scene was already in the can. “I’ll get even,” Tracy grinned as he stepped out of camera range. “This picture isn’t finished yet by a long shot.”

After vigorously pursuing the part of Katherine and turning down another picture to take it, Sylvia Sidney found herself unfazed by Lang’s temperament. “Fritz had a big ego, to put it bluntly. When he walked on the set, he was the master of the show. He wasn’t that tough on me, because he had to get what he wanted on film. He was rough on men … Tracy had a very rough time with him.”

Lang seemed to regard his players as graphic elements; his rigidity put him at odds with his lead actor, a man who needed the latitude to inhabit a character and make him breathe. For Tracy, the real trick to Mob Rule was managing the transformation from the solid, good-natured Joe Wilson, all-around straight arrow, eyes shining with a kind of textbook virtue, to the grim, vengeful shell of a man on the other side of the fire, a walking corpse animated by the sheer power of hate. It wasn’t Lang that gave it to him, yet it’s hard to imagine quite the same effect from another director. Given a comfortable forty-eight-day schedule, Lang, completely unaccustomed to working in a studio where meal breaks were dictated by law, proceeded to direct Mob Rule as if he were back at Babelsberg.

Tracy and Clark Gable shoot their first scene together for San Francisco, 1936. (SUSIE TRACY)

“Lang,” said Joe Mankiewicz,

would have his secretary, affectionately known as The Iron Butterfly, bring on a small silver tray—it might have been a vitamin pill or something more horrible. I don’t know. And a little shot of cognac which Mr. Lang would have as his lunch and continue working. And the crew started grumbling a bit … and the crew came to Spence and said, “Look, what about our lunch?” And so he says, “Yeah, it’s getting late.” And he looked over at Fritz and said, “Mr. Lang, it’s one-thirty and the fellows haven’t had their lunch yet. Don’t you think we ought to break?” And Lang said, “On my set, Mr. Tracy, I will call lunch when I think it should be called.” And Spence took it with that wonderful look, that meek look—and look out when he looked at you meekly—and just took his hand and brushed it across his face, smeared the makeup hopelessly. Take an hour and a half to replace that makeup. And he yelled “Lunch!” and walked, and the crew went with him.

The contrast between Mob Rule and San Francisco could not have been more stark. Where Lang lingered over a scene, making take after take, Van Dyke got in and out as quickly as possible. “He gained a lot by having the actors fresh,” Joe Newman said. “He had that momentum going for him, where he let the actors have sway. If they understood the part, he didn’t indulge in a lot of explanation, and he didn’t believe in a lot of rehearsal.” Though his speed worked largely to the cast’s advantage—no heavy breathing or time for second thoughts—Van Dyke’s stuff tended to be ragged as it came off the stage, and Hyman was already ordering retakes just three days into the schedule.

Tracy was needed only occasionally and seemed to regard his time on the picture as something of a vacation. Still, where Mob Rule was well within his comfort zone as an actor, San Francisco decidedly was not. “We were pretty serious all through that picture,” Gable recalled. “We both had our worries. He was worried about playing a priest, and I was worried about playing an atheist. I had a scene where I was supposed to hit him. How was the public going to take that—seeing a man strike a priest? It took three real priests to convince me I could do it safely if the script had me reforming in the end, and believing.”

The conflict between the two boyhood friends—one who became a roisterer, the other a priest—had been built into the script from the very beginning, when Herman Mankiewicz drafted the first sequence and made notes concerning the general tone and structure of the story. The character of “Father Jim” was introduced during a sparring match with his pal “Aces” Hatfield in which the two traded dialogue between punches. (“No dame’s on the level,” Aces says, to which Jim responds with a quick jab to the chin.) It was Mankiewicz’s idea that the camera reveal Jim as a priest only after he has changed his clothes and emerged from the locker room in the Roman collar. By the time the scene was shot some thirteen months later, Jim had become Tim, Aces had become Blackie, and the scene had been sharpened by Anita Loos with a shot of Tim knocking Blackie clear off his feet, thus establishing that Tim could flatten Blackie if he so wished—a vivid image the audience, in its collective memory, would later call to mind when Blackie socks Tim and the priest, in effect, turns the other cheek.

The heated scene in which Blackie pops Father Tim establishes Mary as the force that comes between the two men. All aglitter in gold braid, black tights, and plumed headdress, she is about to walk out onstage at the Paradise Music Hall, where she will become, in Blackie’s words, “Queen of the Coast.”

“Are you out of your mind?” Tim asks incredulously as he takes her in.

“Why?” asks Blackie innocently.

“Showing Mary like this to that mob out there.”

Mary tells Tim that she loves Blackie.

“It isn’t love to let him drag you down to his level.”

Blackie tells Tim he’s going to marry her, and Tim, with eyes narrowed and jaw set, says, “Not if I can stop you, you’re not going to marry her. You can’t take a woman in marriage and then sell her immortal soul.” He puts out his hand and asks Mary to come with him. The stage manager is knocking, they’re striking up the band.

“I’ve listened to this psalm-singing blather of yours for years and never squawked,” says Blackie. “But you can’t bring it in here. This is my joint!”

“She’s not going out there!” Tim says firmly, and Blackie hauls off and socks him—a moment of shock for both the characters and the audience.

Gable, who never warmed up to MacDonald, marveled at Spence’s seemingly effortless work as the priest: “I couldn’t see what Tracy was worried about. He said he felt like a man walking a tightrope. He had to be human and, at the same time, holy. For my money, he hit the perfect balance between the two from the opening scene.”

Tracy observed his thirty-sixth birthday while working on both pictures (Mob Rule by that time had acquired the title Fury) and he came to regard them as “that double jackpot”—the two best things that had happened to him in his six years on the screen. “When Sylvia Sidney and I put in 21 hours a day on Fury, we did it because we knew that Lang had something; that it would be something worthwhile. It was the same with San Francisco. It was all the difference between that ‘just a job’ feeling that I’d once had in pictures and the conviction that we were getting somewhere.”

The time Lang took seemed partially rooted in the mistaken notion that he had to wear Tracy down in order to get his best performance. According to Joe Mankiewicz, who felt somewhat responsible for Lang’s treatment of the cast and crew (“I put my own personal guarantee that he was great for this movie”), one of the key scenes Lang put into the script was the mob’s ghostly pursuit of Joe in the hours leading up to their conviction for murder. “Now figure Spence in an overcoat … the overcoat flapping in the wind, at night on the back lot, down a very narrow passage followed by a camera car, running for his life. And Fritz Lang letting the car go faster, faster, faster until Tracy was running for his life.”

Tracy and Lang grew to hate each other, and cinematographer Joe Ruttenberg found himself in the middle. “Spencer Tracy said, ‘I can’t stand this any longer,’ but it was Spencer’s first major part [at M-G-M], you know, so he wouldn’t quit. He argued with Lang, and the officers in back of me said, ‘You do whatever you think.’ Mannix says, ‘If they can’t get along with Joe, they can’t get along with anybody.’ ” Tracy consistently gave Ruttenberg what he needed, even when he was at odds with Lang. “In shooting, he knew what he had to do, he minded his own business, he did his work, went back to his dressing room. But he fought with Fritz all the time. They were always fighting, always fighting.”

With actress Sylvia Sidney during production of Fury. (PATRICIA MAHON COLLECTION)

San Francisco was a film largely written by committee, producer Bernie Hyman holding story conferences with his key people—Hopkins, Loos, Emerson—every few days while the picture was in production. Retakes continued into the first week of April, when the group turned its collective attention to the problem of putting the great earthquake together. The mechanical effects developed by Arnold “Buddy” Gillespie, one of three associate art directors on the show, formed the nucleus of the sequence, principally the quake as experienced from the interior of Lyric Hall as the annual Chickens’ Ball is in progress. The set was built on rockers, with breakaway walls of rubber brick and balsa wood, but much of the effect was achieved with the simple combination of jiggling camera and off-balance actors, inserts showing small details of the devastation, the ominous rumblings of the soundtrack setting the nerves on edge.

With his proud mother on the set of San Francisco. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Tracy, who observed the shooting of the scene even though he wasn’t in it, recalled that it was covered with seven cameras. There were 250 extras on the stage, and Van Dyke was careful to explain what they were to do once he gave them the signal. As soon as the building started to shake, though, everyone panicked and surged to one corner. The balcony collapsed, which wasn’t planned, but since no one was injured, the shot stayed in the film. Exteriors—cracking walls, falling debris—were intercut with actors in motion. Whole buildings were crumbled in miniature, bit players fleeing for their lives in front of a process screen. One of the few mechanical effects to incorporate stunt personnel was the splitting of the earth, a shot accomplished with a section of street built on rollers, a hydraulic ram driving rocks and dirt up through the rupture, water spewing through an underground pipe to complete the effect. Tracy didn’t have to endure the simulated quake but was called upon to step gingerly through the rubble in its aftermath, calmly leading the dazed and broken Gable through the tent city of survivors and back into the arms of Jeanette MacDonald, who has weathered the experience in fine voice and feathered gown, every hair in place and her makeup perfect.

When San Francisco was cut together, the result left Hyman and his colleagues deflated. “The earthquake was flat, impersonal, ineffectual,” said John Hoffman, who was brought from Slavko Vorkapich’s montage unit to fix the problem. “It didn’t touch people.” Hoffman set to work giving the picture “a brand new, really convincing quake” as well as a rowdy New Year’s Eve celebration to serve as its bookend. He shot new material—a stone Atlas pitching forward and smashing a vegetable wagon, its horse rearing, its stock rolling, a solitary wheel spinning aimlessly being one of his more memorable images—but his contribution principally was in the editing, the juxtaposition of disaster footage with the reactions of the people in danger, the rhythmic cuts giving size and immediacy to otherwise ponderous footage. But all this was after the fact for Tracy, who did his last work in the film on Saturday, April 25, 1936.

The more modestly proportioned Fury finished two days later, but there were retakes that kept the film open until May 6. The last days were given over to exteriors, largely night work that convinced Joe Ruttenberg that Lang was genuinely a sadist. “He was hell on everybody—actors, technicians, everybody.” The centerpiece of the picture was the mob’s storming of the jail, and Ruttenberg remembered it being scheduled for a Saturday night so that the company could go straight through without a break. “We worked like slaves,” said Tracy. “One day we worked from nine in the morning until five-thirty the next.” Mankiewicz heard that some of the crew members were plotting to drop a piece of equipment on Lang to get him off the picture. “Well, it went from that bad to much worse,” he said, “till I was summoned from my house one night about four-thirty in the morning. Tracy said, ‘Bring the lamp.’ He was going to drop it on Lang.”

The sheriff’s standoff with the mob began with sharp words and angry demands, then accelerated to the hurling of rocks and bottles. Retreating into the jail, the sheriff’s men barricade the doors, firing tear gas out the windows. The ringleaders start battering down the doors, and upstairs Joe Wilson, Lang’s everyman, calls out desperately to anyone within earshot: “Jailer! Jailer! Can’t anyone hear me? Let me out! I’ll talk to ’em! Let me out! Give me a chance!” The mob pushes past the sheriff and his men and overruns the jail, but when they find the keys are beyond their reach, they torch the building instead. Stroking his dog, hard against the corner of his cell, Joe watches helplessly as the smoke thickens and begins to curl around them. “Well, Rainbow, it doesn’t look so good for us.” And down below, as the mob grotesquely watches the building burn in utter silence, Katherine pushes her way through in time to see Joe’s anguished face framed in a barred window and faints dead away.

The last segment, shot midway through production when Tracy and Lang were still on speaking terms, was Joe’s appearance in court after Katherine has discovered that he is still alive. He witnesses the conviction of the people responsible for the torching of the jail, then makes his entrance. The mob’s de facto leader, Dawson, clambers over the others and is sprinting toward the door when he freezes in midstride, his eyes wide with astonishment. There, in reverse, is the dead man himself, moving purposefully toward the bench, clean-shaven once again, his three-piece suit suggesting the very image of a model citizen. “Your honor,” he says, “I am Joseph Wilson.” And the court erupts in a roar of disbelief.

I know by coming here I saved the lives of these twenty-two people. But that isn’t why I’m here. I don’t care anything about saving them. They’re murderers. I know the law says they’re not because I’m still alive, but that’s not their fault. And the law doesn’t know that a lot of things that were very important to me—silly things, maybe—like a belief in justice, and an idea that men were civilized, and a feeling of pride that this country of mine was different from all others—the law doesn’t know that those things were burned to death within me that night. I came here today for my own sake. I couldn’t stand it anymore. I couldn’t stop thinking about them with every breath and every step I took. And I didn’t believe Katherine when she said—Katherine is the young lady who was going to marry me. Maybe some day after I’ve paid for what I did there’ll be a chance to begin again. And then maybe Katherine and I—

As Lang envisioned the film’s final moments, Joe could be seen fumbling in his pocket, and as he says the last words of his statement, his eyes come to rest on what he has pulled from his pocket, nestled among tobacco crumbs and lint—a solitary salted peanut. “I guess that’s about all I can say,” he says and pops it into his mouth. Instantly, the scene would cut to a close-up of Katherine. “Her eyes dimmed with tears, her face aglow in recognition of the Joe she fell in love with, she moves toward him, smiling her forgiveness. ‘Joe—’ She moves closer and closer until her face, smiling with tremendous happiness, blots out everything and the picture fades out.”

Lang later blamed Mankiewicz and the administrators of the Production Code for being forced to shoot an alternate ending in which Tracy and Sidney embrace in court and actually kiss at the fade-out. “A man gives a speech that … is very well written and extremely well delivered, and then suddenly, for no reason whatsoever—in front of the judge and the audience and God knows who—they turn around and they kiss each other. For me, a perfect ending was when he said, ‘Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. God help me.’ You could have shown a closeup of Sylvia Sidney—she’s very happy—he could look at her—period.”

The idea of the kiss came from somewhere inside M-G-M, as the Production Code Administration’s correspondence on the film makes no mention of it. The order to reshoot the close-up of Katherine may well have come from Sam Katz, whose memory of those first desperate rushes would surely have suggested a climactic embrace for the couple. In communicating the order to retake the shot, Mankiewicz told Lang, speaking of the original ending, “Frankly, I agree with you that if this holds up before an audience, it is to be preferred as an ending.” Dutifully, both Tracy and Sidney played the scene as prescribed, and Fury finished after fifty-five turbulent days.

“It was a horrendous test under fire,” Mankiewicz concluded, “particularly for someone like Spencer. It was an important part, an emotional part. And then, of course, to have … a finish of which everybody connected with the picture can only be ashamed.” It wasn’t the clinch that undercut the film’s impact when it had its initial showing, though, but rather the scene in which Lang had the voices and images of the convicted men following Joe down those deserted streets of the city. “We had a first preview,” said Mankiewicz, “at which the film was literally laughed off the screen because Lang had [that] sequence in which ghosts chased Spencer Tracy through the streets. He turned around and the ghosts would disappear behind trees à la Walt Disney. Obviously, that sequence had to be cut out of the film, but Fritz refused to cut anything. It was Eddie Mannix who fired Fritz off the lot and told me to cut the film.3 The subsequent preview was a smashing success, after that one deletion, and the reviews were rapturous.”

But with the motivating sequence removed from the picture, Lang was left to flounder when questioned about the surrendering of Joe Wilson. “I’ve often been asked if Tracy gives himself up because of social consciousness or something like that,” he said to Peter Bogdanovich in 1965. “I don’t think so. I think this man gives himself up because he can’t go on living with an eternal lie—he couldn’t go through life with it. It’s too easy an explanation to say social consciousness makes me do something. One acts because of emotions, personal emotions.”

Fritz Lang left M-G-M a bitter man, blaming Joe Mankiewicz for the cutting of a key sequence and the sweetening of the climax. After the film’s release, Mankiewicz approached him at the Hollywood Brown Derby and offered his hand in friendship and congratulation, and Lang, to his later regret, refused it. His dislike of Tracy was more subtle, as he never had anything but praise for Tracy’s performance in the film. Yet he told Mankiewicz’s biographer, Kenneth L. Geist, that Tracy’s alcoholism had indirectly delayed the picture. “My friend Peter Lorre, a former drug addict, explained to me that when people are deprived of a craving, they turn to something else—Lorre to drink, Tracy to whorehouses. I assume that’s where he’d disappear after lunch, since he didn’t come back till four o’clock. I’d be sitting there with the whole crew, wanting to work, when he’d arrive and say, ‘Fritz, I want to invite the crew to have coffee.’ ”

Tracy’s habit was to have a rubdown at lunch—and a brief nap if he could manage it—but he was present throughout for Fury and only a conflict with the San Francisco company could have deprived Lang of his services. Mankiewicz, furthermore, thought Lang’s insinuation ludicrous. “I don’t think Spence went to whorehouses!” he erupted when asked to comment on Lang’s statement in 1992. “He was much too busy with the ladies! If there ever was an actor who had no reason EVER to go to a whorehouse, it was Spencer Tracy!” He called Lang’s statement “the most unbelievable lie” and then went into the business of the three-hour delay. “How can that be? When Clark Gable was late one half-hour, forty minutes late, on a Victor Fleming movie … Eddie Mannix showed up on the set. Because the [assistant director’s] report goes in: ‘Mr. Gable showed up at such-and-such a time …’ And they come right down. ‘Why were you late?’ Clark, forty-five minutes late, and they ate his ass out. Those stories … if he didn’t show up til four o’clock, what did the crew do? These things are impossible, but they are believed.”

Though Tracy thought Fury a “great document” and a “powerful movie,” he maintained a respectful silence on the subject of its legendary director and vowed never again to work with the man. “Fritz Lang, the director, is a German,” he said tartly in his only public comment on the subject, “and has a technique all his own.”

1 Wellman’s claim to the contrary, this was the only documented fight between the two men.

2 It was Hopkins who once referred to one of the M-G-M producers as “the asbestos curtain between the audience and the entertainment.”

3 “It’s all very well for you directors to want to make pictures with messages in them,” Lang said he was told, “but just remember that Cinderella paid this company $8 million last year—and $8 million can’t be wrong.” The Cinderella story on the current schedule, of course, was San Francisco.