When Tracy was moved the following day, it was to a private room on a restricted floor where, under the name of Charles Newhill, there would be little chance of a Winchell or a Kilgallen catching wind of it. There he began the grueling process of cold-turkey detox, restrained, restless, hallucinating at all hours. Fed a liquid diet of milk, eggs, and fruit juice, he was given daily injections of thiamine chloride and turned every two hours like a premium side of beef.

He strained at the jacket, talking loudly and incoherently and tossing about furiously. He was incontinent, obstreperous, and when they removed the arm restraints, he struck out at the nurses. He thought he saw strange men hiding in the corners of the room and comely young women seated at the side of his bed. Sodium Luminal was administered at eight-hour intervals to promote sleep, and the patient alternated spells of confused drowsiness with fitful, often violent periods of rest.

By the morning of the thirteenth he was quieter, less restive, and said that he had been on a “big drunk” and was having terrible nightmares. He would cry uncontrollably for minutes on end, begging for cigarettes and then talking expansively of getting better. The doctor visited one afternoon and ordered his restraints removed. At once he started smoking and talking cheerfully of California. By the first of the week he was bathed, shaved, and welcoming visitors. “Very pleasant and friendly,” the chart read. There were quiet conversations with the evening nurses, but still there were prolonged episodes of weeping. When plagued by intervals of restlessness and loud moaning, he was ordered off caffeinated beverages—coffee and Coca-Cola—and his sleeping briefly improved. Soon, though, he was fearful and restless again, and the medications no longer seemed to be working. He fell into a pattern of asking to be sedated just so he could get a little sleep, but then he was rarely out for more than two or three hours at a stretch.

Discharged on May 19, Tracy was still unable to sleep very much, but he was finally free of the symptoms of alcoholism. He made his way back to Los Angeles, where Kate was waiting for him and where her own Pacific tour was subsequently canceled because of “ill health.” The events of the preceding three months had badly shaken them both, and now Tracy would be entering a period of unprecedented sobriety.

Producer Arthur Hopkins, who directed both Tracy and Hepburn in their Broadway debuts, had monitored the situation and kept in close touch with Kate in California. “Spence,” he wrote her,

is finding his way out … Spence, in his meditations, will learn discrimination. He will recognize the enemy and reject him. This is not a struggle, for struggle gives the adversary strength. It is not Will Power or Resolution. It is realization of God’s presence and God’s desire to strengthen us and make us useful to Him. You too, Kate, in strengthening Spence, strengthen yourself. Faith increases as you draw upon it. It is the accumulation of that [which] vanishes when not drawn upon.

Above all, Spence must learn that a sense of shame is vanity and is an affront to God … when we pray, it is God who is praying with us. He wants us to understand and be free. Spence is learning this, and you and I with him.

By 1945 Robert Emmet Sherwood was widely regarded as the dean of American dramatists, a man whose death was likened by Maxwell Anderson to “the removal of a major planet from a solar system.” The author of such varied fare as The Road to Rome, Waterloo Bridge, Idiot’s Delight, and Abe Lincoln in Illinois, Sherwood had enjoyed a string of critical and commercial hits stretching back to the 1920s. At the time he proposed to write a play for Spencer Tracy, he held three Pulitzers for drama—one for each of his previous three plays. In the uncertain business of the American commercial theater in the days immediately following the Second World War, there was nothing more prestigious—nor closer to a sure thing—than a new play from the redoubtable R.E.S.

Tracy, of course, had attracted plenty of feelers from Broadway, most notably from Kate’s friends at the Theatre Guild, who took his interest in The Devil’s Disciple as a firm commitment and eagerly announced it to the press in August 1941. Paul Osborn put up an original on the basis of Tracy’s praise for Madame Curie, and Oscar Serlin reportedly offered Metro “a terrific amount of money” to lend Tracy for his production of The Moon Is Down, which combined the talents of John Steinbeck and director Chet Erskine. By late 1943 the Guild’s Lawrence Langner was sweetening the pitch by suggesting plays that would accommodate both Tracy and Hepburn, Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude and Marco Millions being his top choices. So convinced was Langner that Tracy and O’Neill would make a powerhouse combination, he tried arranging for Tracy to travel to Contra Costa, rationing notwithstanding, to meet the famously reclusive playwright. At the time, however, Tao House was in the grip of a flu epidemic and hospitable to no one.

In a subsequent letter to Langner, O’Neill thought The Great God Brown “a good bet” for Tracy but warned against Strange Interlude (“Nina’s play—always has been”) and Marco Millions, which he wasn’t keen on seeing revived. “My best bet for Tracy would be Lazarus Laughed,” O’Neill wrote. “Now give heed to this and re-read it carefully in the light of what that play has to say today. ‘Die exultantly that life may live,’ etc. ‘There is no death’ (spiritually) etc. Also think of the light thrown on different facets of the psychology of dictators in Tiberius and Caligula. Hitler doing his little dance of triumph after the fall of France is very like my Caligula.”

Though Tracy was genuinely thrilled with the substance of O’Neill’s letter, he read Lazarus, with its masked chorus and its Greek pretensions, and frankly admitted he did not understand it. Kate didn’t either, wasn’t much on Strange Interlude, and didn’t know Marco Millions at all. When queried, Langner said that even he couldn’t fathom Lazarus, which, tellingly, had never had a New York production. “I have read it ten times,” Langner said. “I think you have to be a Roman Catholic to really understand it. Maybe if Spencer and Gene got together they could work something out of it, especially as he seems to be willing to rewrite and might clarify for Spencer. I will drop Gene a line and find out whether he would like to talk about it to Spencer.” O’Neill was ill, though, and by the time his precarious health improved, Tracy was committed to Sherwood and his new play and there wasn’t much point in discussing the matter any further.

The gangling Sherwood was a founding partner of the Playwrights’ Company, a producing organization specifically established to stage the works of its five principals, who, besides Sherwood, were Maxwell Anderson, Elmer Rice, S. N. Behrman, and the late Sidney Howard. After making his report to the navy, Sherwood set about developing his new play with characteristic discipline, producing two acts and fifteen scenes in little more than a month. As was the custom, Sherwood circulated the playscript among his colleagues at the company and was ready by the end of June to bring it west, where Tracy was nursing a torn leg muscle. “Madeline and I hope to arrive Beverly Hills about July 1st,” he cabled on June 22, “and will then show you the manuscript and talk about it as planned.”

Bearing the title Out of Hell, Sherwood’s play followed the pattern of his two previous works, an earnest protagonist nobly chucking it all for the greater good of society, plunging himself into politics or, in this case, war, and suffering, in the end, a martyr’s fate. Delayed in his travel plans, Sherwood airmailed a copy to Tracy on the twenty-eighth, dispatching another to actor Montgomery Clift (who he hoped would play opposite Tracy) the next day. Tracy read the play at once, reportedly within hours, and both he and Kate signaled their enthusiasm. “I felt he had things to say,” Tracy said of Sherwood, “things well worth saying that you can’t say in a picture.”

In New York the playwright spoke with J. Robert Rubin, M-G-M’s vice president and general counsel, and the terms for Tracy’s services seemed satisfactory. When he finally reached Los Angeles, Sherwood and his wife put up at Kate’s rented house on Tower Road, where there followed a series of convivial discussions. “You may be making a mistake with me,” Tracy felt compelled to warn him. “I could be good in this thing, all right. But then, who knows? I could fall off and maybe not show up.” At six feet eight inches, Sherwood towered over his prospective star, his rugged face set off by a neatly trimmed mustache. “Spencer, all I want for myself,” he replied with a characteristic pause in the middle of his statement, “is to see this play played once by you.”

He nearly got his wish.

In their early discussions, both men expressed a preference for Garson Kanin as director, even though Kanin’s experience in directing for the stage was minimal. In London the army captain happily accepted the assignment, wondering only if Sherwood had the organizational pull to get him sprung from the military. Sherwood, working through both President Truman and his army chief of staff, General George C. Marshall, assured him that he did.

A letter of agreement dated July 13, 1945, committed Tracy to rehearsals beginning around Labor Day and an out-of-town opening “on or about” September 28. In exchange for playing Morey Vinion, Sherwood’s quixotic hero, he was to receive 15 percent of the gross weekly box office receipts. A provision giving him the option of investing in the show on a dollar-for-dollar basis was added to the contract, but it seemed unlikely that Tracy would buy in.

Sherwood’s sojourn in Beverly Hills sparked the first of a seemingly endless string of rewrites. Nobody was lacking for suggestions—not Tracy, not Kanin, certainly not Hepburn, nor Kanin’s wife of three years, actress-playwright Ruth Gordon. According to Madeline Sherwood, her husband had already done “considerable revision” by July 26 and had sent new copies to his associates at the Playwrights’ Company. There was another round of fixes almost immediately, giving the play, among other things, its permanent title—The Rugged Path.

Hepburn, who was convinced now more than ever that the best thing for Tracy would be, as their friend Constance Collier put it, to “find release from celluloid fetters,” declared she was going to see him through this thing and passed on the chance to play Isabel Bradley in George Cukor’s proposed filming of The Razor’s Edge. Tracy tried dissuading her from turning the picture down, saying that he really only needed her for the last week of rehearsals and maybe the week of the actual opening, but to no avail. She had, by this point, convinced herself that she was absolutely essential to Spence’s well-being, both personal and professional, and that he was incapable of managing the task without her.

When he heard the wartime limits on gasoline had been lifted, Tracy decided to motor east with Carroll, leaving Kate in California to further contemplate her decision. The men had so much tire trouble the first two hundred miles, they reconsidered, turned around, and set off again via rail, Hepburn, this time, accompanying them.

The train was booked solid and it was no secret who was on board. (Lawrence Tibbett, the acclaimed baritone of the Metropolitan Opera, was also a passenger.) At Freeport the boys visited with family—their uncle Andrew, aunt Mum, Jennie’s daughter Jane, who was working at the USO in Savanna, and Kathleen and Henry Willits, who came over from Dubuque. They took a private dining room in the nearby village of Cedarville and had an elaborate family dinner, Spence talking freely of the work ahead. “I don’t know whether this is going to work or not,” he confided. “In the first place, I don’t know if I’ve got the voice for it. I haven’t been on the stage for years and years and I don’t know if I’ll make it. But I feel I want to try it.” The woman who ran the kitchen had brought a couple of teenage girls in to help with the serving. “This little girl was just shaking,” Jane Feely recalled. “The movie star! She was passing the plates around, and Uncle Andrew said, ‘This is Mary Lou Whatever.’ And she said, ‘How do you do … Do you know Van Johnson?’ Oh, Spencer loved that. He said, ‘Yes, I do. What’s your name? I’ll get you an autographed picture of Van Johnson. Carroll, see to it.’ ”

In New York he had an escape clause inserted into his contract, giving him an out during the first three weeks of performances and another during the New York run of the play. He had, he explained, full confidence in Sherwood’s work; it was the lead actor who gave him pause. Could he still manage the sustained concentration he’d need to carry a play? Could he achieve the same level of purity he had learned to put forth on film? “Once,” Kate remembered, “I asked Spencer some such foolish question like, ‘How did you like my play acting?’ and he stared at me for a moment and said, ‘That’s the strangest remark I ever heard. What is play acting? Do you mean the tricks some people pull on stage? If that’s supposed to be acting, I don’t like it.’ ”

Rehearsals for The Rugged Path commenced on the stage of the Barrymore Theatre on September 3, 1945. Johnny, in the hospital, had a telegram from his father the next day:

EVERYTHING WENT WELL EXCEPT I AM SCARED.

In Morey Vinion, Sherwood had fashioned a character as fitted to Tracy as a second skin—a career journalist, outwardly happy yet inwardly brooding and dissatisfied in his role as the “embattled liberal” in an otherwise conservative newspaper. “He’s never been really happy,” his wife admits. “Well—not since the first few months, and I sometimes wonder about how he really felt even then. When he got down to work in Europe, he began to take everything to heart as though he were personally involved, instead of just being an American reporter.”

She asks him: “Do you want to get out of here, Morey?” And he tells her no, he doesn’t, that he just wants to “stay put” for a change. “I want to have my own home in my own country. I told you I wanted my own home, and I meant it.” Actress Martha Sleeper played Morey’s frustrated wife, married to a man “incurably restless by nature,” a “damned good newspaperman,” which meant, as his father-in-law told him, “you’ll be a damned poor husband.”

MOREY

Oh, we got along all right, Harriet, despite all reports to the contrary.

HARRIET

Yes, we’ve got along. Because we’ve both had good manners.

“One of the banes of the existence of any playwright or director,” said Garson Kanin,

is the actor, especially the star, who doesn’t really know his part. They sort of know it. In the Broadway theatre, I think it’s more common for a player to know his part. In films [it’s], “Oh, I’ll take a shot at it.” But Spencer was absolutely meticulous about learning his part, and learning it way ahead of time, and learning it so accurately. I used to kid him sometimes; I’d say, “Spencer, you even learn the typographical errors.” He learned it absolutely exactly as written. Of course, after 15 years his theatre machine was a bit rusty and he was aware of that, but it didn’t take him long—three or four days—and he was absolutely in there like a stage actor who had acted every night on the stage for 15 years.

Nearly three weeks into rehearsals, Tracy’s contract with the Playwrights’ Company remained unsigned. He now wanted, it seemed, a 25 percent stake in the show but was unwilling to put in any of his own money, M-G-M’s Rubin having advised him that an investment on his part would likely put him in “an unfavorable tax position.” Victor Samrock, the company’s business manager, took up the matter with Carroll Tracy one morning, saying they were in no position to grant a 25 percent share of the profits without a commensurate investment in the show. Tracy was, moreover, being offered the exact same terms accorded the Lunts and Katharine Cornell and Helen Hayes. Carroll said how sorry he was that the matter had not been settled in California and he assured Samrock that everything would be all right “in time.” Later that afternoon, after conferring with his brother, Carroll again sat opposite Samrock and said, “Well, if you can’t agree to Spencer’s request, then you better get somebody else.”

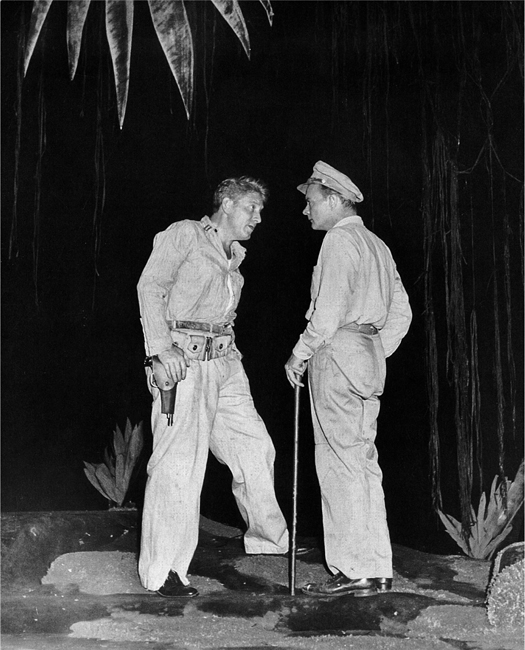

Conferring with Captain Garson Kanin and playwright Robert Emmet Sherwood during preparations for The Rugged Path, 1945. (PATRICIA MAHON COLLECTION)

Tracy was ready to bolt, his confidence undermined by the fractious rehearsal process that comes with any new, untried work. Samrock tried laughing the thing off, repeating the gist of their earlier discussion and ticking off the costs associated with a production on the grand scale of The Rugged Path. “Carroll was quite friendly about it all,” Samrock recalled, “and finally suggested, ‘Well, I think I’ll go up to Rubin’s office and have him call John Wharton [co-director and general counsel for the Playwrights’ Company] and maybe the two of them can settle it.’ ”

If the role of Morey cut too close at times, Tracy’s discomfort—his projection of temperament—came out in his dealings with Samrock and Wharton, where Carroll could serve as both mouthpiece and whipping boy. In rehearsals Kanin found him “imaginative, resourceful, malleable”—a revelation. What he achieved was a clarity of interpretation that stretched beyond the intelligence, personality, and stamina he typically brought to a role. “His whole approach,” said Darryl Hickman, “was to externalize as little as possible.”

Driven by an abhorrence of artifice and a natural terror of monotony, Tracy was constantly distilling the character to its essential elements, his stage effects coming wholly from within, all clean, sharp lines, lucid and completely free of the tricks “some people pull on stage.” When a scene required him to emerge from the ocean after five days of being shipwrecked, he told Kanin he would not wear an appliance designed to simulate a growth of beard.

“It’ll look ridiculous,” Kanin argued. “It’ll bother the audience.”

“No, it won’t,” countered Tracy.

“Why won’t it?”

“Because I’ll act unshaven.”

The company was large, the production unwieldy, the script unready and better suited to the conventions of the screen. The first public perfor-mance of The Rugged Path was set to take place in Providence on the night of September 28, 1945. Recalling his abrupt dismissal from the Albee Players in 1928, Tracy relished a triumphant return to the city. “The play was sold out all three nights,” he said, still harboring a grudge against the Albee stock’s old general manager, Foster Lardner, “and I’ve always hoped the bastard tried to get in and couldn’t get a ticket.”1 Kate, who was in constant attendance throughout rehearsals, appeared on the arm of Arthur Hopkins. The Metropolitan was a big auditorium, plain and thoroughly unsuited to the demands of live drama. Tracy filled all three thousand seats, and at intermission it seemed as if all three thousand patrons wanted a close look at Hepburn, who had placed herself on display in the front row. “I felt,” said John Wharton, who observed the procession, “that it was not calculated to increase interest in the soul-searching of the character Tracy was portraying. But this was minor. What was major was the inexplicable aura of failure that began to settle over the play. Except for the one scene where the men abandoned ship, the aura increased.”

It was nearly 11:15 when Tracy took his curtain line. “I’m not worried about you fellers,” he told his ragtag band of guerrilla fighters as they faced certain death in a Philippine jungle. “I wouldn’t trade you for the best they had at Valley Forge or Gettysburg or the Normandy beach-heads. You may not have much to fight with, but you know what you’ve got to fight for. That gives you dignity. And if the rest of the world—all the people back home who see the war only as a lot of little arrows on little maps—if they don’t realize what you’ve fought for, and don’t achieve it, then I say God damn them—God damn them—God damn them to all Eternity.”

“Spencer was superb,” said S. N. Behrman, “a marvelously sustained performance, very quiet, intensively felt. By that time Bob’s reputation had reached a pitch approaching infallibility. In the intermission a well-known lady expressed her disappointment: ‘Sherwood builds up a crisis for the hero which he solves by giving him a job on a destroyer where he fries eggs.’ I left the theater with Arthur Hopkins, a meditative man. He said: ‘No playwright should be given as much power as Bob has been given. It distracts him from his true vocation—writing plays.’ ”

The Variety notice lauded the play’s missionary intent while bemoaning the sight lines and the wretched acoustics of the hall, factors that doubtless informed the audience’s tepid response. There was also the vague feeling among the out-of-towners that they had seen it all before—trademark Sherwood with a coating of Hollywood star power. “Sherwood,” said Wharton, “knew something was amiss; he never fooled himself. But this time he couldn’t find the way to fix it. Tracy became worried; there was talk of closing out of town. Indeed, Miss Hepburn, whom I had known for years, made a comment one day which astonished me. She said, ‘John, I think it will take a lot of courage to open in New York, and Spencer hasn’t got that kind of courage.’ ”

“Desperate changes” were made between Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., where The Rugged Path was set to open a two-week stand at the National Theatre on Monday, October 1. Rehearsals grew tense as Tracy wrestled with all the new material, and when Kanin one day said to him, “We’ll iron this out tomorrow, Spence, okay?” Tracy reportedly threw back, “If I’m still here tomorrow!” as he stalked out of the theater. The fact that he hadn’t yet signed his Equity contract put the whole enterprise on a precarious footing, and Samrock, for one, was certain that disaster would accompany the Washington opening.

The first-night audience was studded with big names, including Justice and Mrs. Felix Frankfurter, Senator and Mrs. Arthur Vandenberg, and General and Mrs. Alexander D. Surles, yet it was Kate’s appearance, hair upswept, in a long red evening wrap, that set the most necks craning. She attended with her friend Laura Harding, the American Express heiress, and when the curtain went up, she could plainly see that Spence was nervous. “Now he was never nervous,” she said. “Never nervous. And the thing hadn’t been going too well, and I thought, ‘Oh dear, is he going to sort of … take that road?’ And Laura Harding said to me, ‘Is he nervous?’ And, of course, I said, ‘Oh, no, of course he’s not nervous.’ But he finally overcame it. But when you are aware that the material that you’re playing is not of great interest to an audience, it’s tough sometimes to keep from being nervous.”

All the reservations Tracy had about his own capabilities—voice, technique, mastering an ever-changing part—proved to be completely without merit. Kate, in a letter to M-G-M makeup artist Emil Levigne, described his performance as brilliant: “[H]e really delivers the goods—easy, funny & moving—& I think the audience is positively bewildered by his naturalness—& he can be heard in the very last row—I know this because my usual spot is standing in the back …” Irene Selznick, escorted that evening by New York Post publisher George Backer, did not expect to see Tracy in the Sherwoods’ suite after the opening, but she took the absence of Garson Kanin as an ominous sign. “Curiously,” she wrote, “there seemed to be a party going on; several of Bob’s friends, Washington celebrities of that period, were on hand—all very interesting, except that nothing constructive was happening. The play had problems, but not anything that couldn’t be solved, and I thought it had a great chance.” She watched as Anderson, Rice, and designer Jo Mielziner waited to confer—“twiddling their thumbs”—and Sherwood, all aglow, drifted into a spirited rendition of “Red, Red Robin”—a sure sign that nothing substantive would get discussed that evening.

Tracy fell ill with grippe in Washington, alternately dripping with sweat and then trembling with chills, knowing the first performance he missed, however sick he might legitimately be, would be laid to booze. Loading up on sulfa drugs, he struggled to the theater eight times a week, vomiting in the wings and, in Kate’s words, looking back on his life at Metro “as a paradise which he didn’t appreciate.”

The show limped into Boston, where the Hub critics laid it out extravagantly. Louise trained up from New York and was dismayed by what she saw. “It didn’t amount to anything,” she said. “He didn’t want to stay there. He always said, ‘Should I get out of it?’ It wasn’t up to what he had hoped, and he just wanted to get back.” Kate, of course, was in Boston as well, and it was her constant bucking up that kept him with the show, even when it was apparent that Sherwood wouldn’t be able to fix the play’s most fundamental faults. At the hotel, the author and his partners spent four hours trying to talk Tracy out of quitting; Sam Zolotow reported in the New York Times that he would be leaving the show on October 27, causing the vigorous advance sale in New York to come to a dead halt. Through Carroll, Tracy told Victor Samrock that he would stay with the play only if he could give a two-week notice at any time during its Broadway run, and Samrock, desperate to get the show into New York at any cost, had little choice but to agree. On October 22, his stamina gone, Tracy wired Samrock:

TWO WEEKS CONTRACT SATISFACTORY. OPENING NEW YORK NOVEMBER 10TH.

After nearly four months of back-and-forth, he had finally signed his Equity contract.

On the morning the show moved into New York, Garson Kanin came across Hepburn scrubbing the bathroom floor in the star dressing room. He wrote: “In the ten days prior to the New York opening all the important working relationships had deteriorated. Spencer was tense and unbending, could not, or would not take direction, which amounted to the same thing.” With a Life magazine cover story pending that would focus national attention on the show, Tracy approached the New York opening as if preparing to face a firing squad. “I was a basket case,” he remembered. “A basket case!”

Kate had taken him to see Laurette Taylor’s gut-wrenching performance in The Glass Menagerie and he had come away regarding Taylor, whom he had never met, as “the greatest actor I ever saw and the greatest this country ever produced.” (As Hepburn said, “She and Spencer had a tremendous amount in common, because they never drove a part—they just let it happen.”) The day of November 10, his stomach in knots, Tracy left for the theater resentful of Kanin, Samrock, Sherwood, and the whole fraternity of critics who were doubtless planning to flay him alive. “When I came into my dressing room to get ready to go on, there was a little carnation stuck with a black pin and a little note written on tissue paper that said, ‘Dear Mr. Tracy: I have always been a great fan of yours. Welcome home. Laurette Taylor.’ She had stopped on her way to the theater and left it. So I said, ‘Boys, if the lights go out now I still win. Fuck it.’ I was relaxed that night, opening night.”

Kate had been hovering, hoping he could concentrate. “It touched him so,” she said of Taylor’s thoughtful gesture. “He was so thrilled, because he had wild admiration for her, and he just put it in his button hole. When he came on, I thought, ‘Ooh. Well. Never saw that [carnation]. I wonder who sent that?’ But it certainly made him feel absolutely there.” With the company thoroughly demoralized, Kanin thought the performance promising: “Spencer rose to the occasion and gave an overwhelmingly magnetic performance, but somewhere, about halfway through, the dramatic line failed to sustain. The play lost the audience and disintegrated.”

“No newspaper man could ask for a better model than Mr. Tracy,” averred Lewis Nichols of the Times. “Leisurely and assured, he is one of the most likable members of the fourth estate and whatever estate it is to which actors belong. His Morey Vinion is an honest man, an able editor, and a quizzical cynic; the performance is indeed fine. But Morey Vinion is almost the only cleanly-written part.” Of the play itself, Nichols lamented its lack of power, Sherwood having abandoned the role of prophet and “forceful advocate” for that of historian, permitting the flashback structure to drain it of all passion. “To get the bleak news over immediately: Robert E. Sherwood’s first play in five years has not been written with his best pencil.”

The story was the same all over town. The Herald Tribune: “Robert E. Sherwood has mistaken a stage for a podium. The Playwrights’ Company’s offering emerges as a series of animated editorials rather than a challenging play.” P.M.: “It is most palpably not a good play … It is not even at this moment in time a very provocative commentary on the issues confronting the world … Tracy’s acting is likable, natural, and not unconvincing.” Time: “One trouble with The Rugged Path is that it is not dynamic enough to avoid seeming emotionally dated.” The Sun: “The new play is lacking in dramatic progression. It is more message than it is good theatre … Tracy … gives a solid, tender, biting performance.” Andrew Tracy, writing his son Frank in China, summarized the reviews by reporting that the play seemed out of its time. “It’s what they call, in the movie business, a turkey,” he carefully explained.

Unlike Louise, who considered the gradual evolution of a character one of the great creative pleasures of the stage, Tracy, after fifteen years of working solely before the lens of a camera, could no longer welcome the audience into the process. Used to settling a performance and then moving on to the next shot or the next scene, he was effectively done with Morey Vinion by the end of the first week. “I couldn’t say the same goddamn lines over and over and over again every night,” he later groused to a friend. “I’d forgotten how boring that could be, how deathly boring that was. I wasn’t creating anything. At least every day is a new day for me in films. Every day is new and when I get through with this film I’ll go right into another one, and that’s new. But this thing—every day, every day, over and over again.”

There settled over the company a sort of grand acquiescence, as if everyone knew that it was Tracy who was keeping the play open and yet resenting him all the same. Anxious to keep their star satisfied and prove to him that he was indeed doing well, Victor Samrock had a number of standing room stubs added to the nightly till in order to bring the show to straight capacity business. The producers also bought several box seats to show a clean sheet on the statement. Tracy, in turn, kept to himself, arriving on matinee days at 2:46 for a 2:45 curtain and rarely speaking to the other members of the cast. Somewhere toward the end of the first week, he granted an interview to Eugene Kinkead of the New Yorker. “I can’t say I’m enjoying myself,” he said. “I’m gratified at my personal reception by the critics; I’m sorry they didn’t like the play. I’ve looked up the record of plays that have been panned, plays with so-called stars in them, and I’ve never seen an instance of a serious play holding up under the kind of reviews we’ve had. Still, you find standees at all performances. I’m amazed. Our audiences give us hearty, healthy applause. I’m frankly a little confused.”

He went on:

Metro wants me to come back. My next picture will be either Sea of Grass by Conrad Richter or Cass Timberlane—probably the former. I don’t know what to do. I’m terribly upset. Sherwood to me really has great integrity, and I know the fabulous figures he’s been offered to write pictures. It’s a little discouraging. I think there’s some of the finest writing in the play I’ve ever seen. I was amazed to find he was not treated with more respect by one or two of the critics. I’ve never known integrity like his. It’s damned, damned unfortunate. Anyway, I’ll stay with it until my boy John, who is flying from California soon, has seen it. He wants to see me act. I’d like to come back in another play, and in another play by Robert Sherwood.

Kinkead’s piece ran in the “Talk of the Town” section of the magazine’s issue of November 24, and the swell of organizational outrage was instantaneous. Tracy’s statements, however well intentioned, brought an immediate decline in advance sales. Sherwood also considered it “one of the very worst blows of all” in their struggle to sell the movie rights. “This, of course, was followed by numerous newspaper items indicating that Tracy might leave at any moment, and the show was marked with the stamp of doom.”

There were a few cast replacements—actors leaving for more promising jobs—and the gate started to slide as Christmas approached. Capacity at the Plymouth was $26,268 a week, but in the play’s second month the average hovered at around $20,000, dipping some weeks to below $19,000. Playing to empty seats, Tracy feared his stature in Hollywood might suffer and let it be known that he was thinking of leaving the show on January 5. Sherwood, pleading poverty, had taken a job with Sam Goldwyn writing the screenplay for a home-front picture called Glory for Me,2 and from California he appealed to Tracy to allow the play one hundred performances, which would take it into the week ending February 9, 1946. “We are still the biggest legitimate gross in town,” he stressed, “and will undoubtedly remain so through these bad two weeks then back to capacity.”

Tracy said that he might reconsider his closing date, a statement that, like the previous one, got reported in the New York Times. Reacting to the damage such uncertainty did to the advance sale, both Samrock and Sherwood pleaded again for a definite decision. “I understand your problems,” Sherwood told Tracy in a day letter, “and know that despite them you have given a magnificent performance in my play. But you must also understand, Spencer, that neither I nor the rest of the Playwrights’ Company could get away with the obvious lie that we would close the play January fifth for any reason other than the fact that you are leaving it. This is not an attempt to trap you into extending the run. It is simply the situation in which all of us are placed.”

Tracy took his heaviest blast in the press on December 23 when John Chapman of the Daily News bitterly assailed him under the headline HOLLYWOOD GO HOME: “The sooner Spencer Tracy goes back [to Hollywood], the better—and he should stay there.” When the studio put out word that Tracy’s return to Los Angeles was “imminent” and that he was wanted to play the role of President Truman in The Beginning or the End, Bob Considine’s topical story of the atomic bomb, Victor Samrock seized control of the situation. On December 27 he notified the cast that The Rugged Path would close on January 19, 1946, completing an engagement of ten weeks, if not the one hundred performances for which Sherwood had so vigorously lobbied. The same day, the wire services carried the news that Tracy, solely on the strength of Without Love, had retained his position as one of the top five stars in America in the annual Motion Picture Herald poll of box office leaders.

With Robert Keith onstage in The Rugged Path. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The closing announcement triggered a recap in the January 2 issue of Variety, where Tracy’s departure, the paper said, would not only mean “plenty of red for the Playwrights’ Co., but a loss of employment by supporting actors.” The star’s desire not to continue, the item went on, was responsible for the fold. “It cost $75,000 to produce Path and the loss at this time is placed at more than $40,000. Show is costly to operate and virtually no profit was earned out of town. Grosses at the Plymouth have been exceptional, and it was figured Path could play well into the spring.” The paper laid the blame squarely at Tracy’s feet, suggesting the show had depended on the star’s “whims” from the start.

No mention was made of Sherwood’s negative reviews, which would have doomed the play with most any other star, nor Tracy’s positive reviews, which were practically unanimous. Variety published on a Wednesday, and Carroll called Victor Samrock the same day to say that Spence was in “quite an uproar” about it. “Am seeing the great man tonight,” Samrock promptly advised Sherwood in a letter, “but now that the play has announced its closing, I am not worried about Spencer’s innermost feelings, nor will I try to assuage his soul-searching doubts. On second thought, I will do these things if he promises to buy the moving picture rights for Metro.”

Howard Dietz called editor Abel Green and arranged for Variety mugg Arthur Bronson to meet Tracy in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria and hear his side of the story. “I take the theatre seriously,” Tracy told Bronson. “My record is good in it. The people I worked for—Herman Shumlin, the late George M. Cohan, and Sam Harris—they would have vouched for me.” He denied that he was “running out” on the play and said the show was closing “for a simple, old-fashioned reason—it wasn’t doing business.” He pointed out that five other actors had already left and that Sherwood himself was out working in California. It had, in fact, been Sherwood who insisted on bringing the play into New York when it wasn’t yet in shape. “If I had left,” he said, “the play wouldn’t have come in.” Truthfully, he told Bronson that it was the producers who gave him—and the other actors—notice, and not the other way around. He then suggested to Bronson that he had never threatened to quit—a baldfaced lie.

Samrock was disappointed that there was no spike in business when the closing notice went up. He estimated the week of January 7 at $18,500 and felt the following week would be a little better. “I frankly thought the announcement would increase business,” he said to Sherwood in a letter,

but even so, I constantly have to catch myself up by realizing that $18,000 and $19,000 is still a lot of business in any country for any play. I would like to add that the lack of increase in business has hurt Mr. Tracy’s pride (if he has any left). He has been constantly asking me to have you make a statement that the company is closing the play because of lack of business, and I have constantly been pointing out to him that while the play is not selling out, it is still doing good business, which shows that he is a draw, and I see no reason for making any statement at this stage of the game because it would only serve to create animosities.

Garson Kanin had gone off to direct his own play, Born Yesterday, and actor Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., who replaced Rex Williams in the part of Gil Hartnick, one of Vinion’s colleagues on the paper, marveled at the spectacle of Tracy giving the actors notes after every performance. “Despite his notable achievements, he aroused little respect from our cast by insisting that all the actors maintain an artificially high pitch and level of performance,” Zimbalist wrote in his autobiography. “When he slipped in comfortably underneath everybody else, the audience would say, ‘He’s so natural!’ His notes comprised a list of those whose energy level was dropping (almost to normal). We all knew what his game was but were helpless to do anything about it.”

When the last performance took place on the night of January 19, Samrock reported to Sherwood that the cast felt miserable “because the full impact of what can happen conveyed itself to them only after the last performance. It was sad and a little more than depressing.” A letter of thanks over Sherwood’s signature was distributed to the cast: “As a kind of final curtain on my relationship with Spencer, I must tell you that all his talk the last few days was, ‘Where did I go wrong?’ The only other note worth mentioning is that he fully promised me, without any prodding on my part, that he was returning to Hollywood and would proceed with all that was in him to sell the moving picture rights of The Rugged Path.”

On January 24, Sherwood addressed both Samrock and press representative William Fields in acknowledging what both men had gone through in the interests of the play and their friendships with him. “I appreciate it very deeply, and I bitterly regret the initial mistake that I made when I first put my faith, and the fruits of long labors, in one who had proved, over and over again, that he possesses the morals and scruples and integrity and human decency of a louse. This, unfortunately, has not been merely one of those irritating experiences that one can laugh off and quickly forget. There certainly was an ugly kind of poison which spread to all of us and it is no easy task to get rid of it. I know we will get rid of it but, speaking for myself, it will not be forgotten.”