Frank Tracy sat in his Florida apartment and contemplated the spectacle of Dorothy and Louise Tracy. “Dorothy and Louise were two very different kinds of people,” he said. “Dorothy and Louise, my God. Nothing wrong with Dorothy morally or whatever, but she was a chatterbox. Never stopped talking. Drive you right out of your mind. My dad used to say, ‘For Chrissake, is she coming over here? God, as soon as she hits the door, that’s it.’ Never had anything to say. Nothing was ever amusing, informative, nothing. Carroll would just sit there and smile.”

In particular, Frank recalled a time when Carroll and Dorothy Tracy were visiting Freeport. “I was home for a weekend or something, and I remember sitting in the living room talking about Spence and Louise. My mother or father said, ‘Well, they never got divorced. That’s a plus.’ And Dorothy said, ‘Well, of course not. She’s not going to give up being Mrs. Spencer Tracy. She’s never going to give that up.’ They seemed very … the word isn’t bitter … critical maybe. I was very surprised.”

Dorothy’s perception of Louise and her use of the name was more widespread than Frank could have imagined. Many in Spence’s circle felt the same way, though Kate herself never said a word. “Being Mrs. Spencer Tracy publicly was more important than being the wife of Spencer Tracy,” George Cukor said of her, but it was simplistic to assume that Louise somehow needed to bask in the glow of her husband’s celebrity. “She was certainly a saint,” Jane Feely said, “but in the very best sense of being a saint. She was a true servant of God and a true carrier of the cross, but in a very human way, which is what a saint is. She grew and grew and grew, that woman … Especially as she grew in stature with the Clinic, she became a person of whom she could be very proud, and of whom Spencer was very proud. Whatever she may have felt, whether she knew or she didn’t know, she knew who she was. Maybe better than he knew who he was. And I think he envied that. She had found herself in that.”

Louise was now sixty-four, as white-haired as her husband and no longer able to manage an enterprise that had grown beyond her wildest dreams in size and complexity. “I am trailing the Clinic by many lengths,” she wrote her friend Mary Kennedy Taylor in 1958. “I would be, even if I had plenty of time. It has grown too big and too involved for my simple mind. Thank goodness we have a good administration and staff—over 30 of us now.” The original building was expanded in 1956 with a two-story wing and basement, increasing the overall floor space on the new campus to some thirteen thousand square feet. By 1960, families in fifty-six countries were enrolled in the clinic’s yearlong correspondence course, the newest translations being in Croatian and Serbian.

“She would say, ‘I am so tired,’ ” Jane remembered. “She was overwhelmed with how big the institution had become. I think she felt inadequate to it because she hadn’t had a formal education. She had had to not only establish and work on this clinic, she had to educate herself in this field and she had become an expert, but it had taken a lot out of her. A lot more than I think anyone, maybe even she, realized.”

In 1954 Dr. Edgar L. Lowell was recruited from Harvard to assume the role of administrator, freeing Louise from the day-to-day responsibilities of management. As director in charge, she still oversaw the clinic’s core services—consultations, hearing tests, parent classes, the demonstration nursery school, the correspondence course, and the summer sessions—while Dr. Lowell started research and teacher-training programs. From everything he had heard, Edgar Lowell was surprised to find that Spencer Tracy was as interested in the clinic’s business as he apparently was.

“I was always very gratified,” he said,

that he read my reports. I’m a great one for writing things out. Numerable times Mrs. Tracy would say, “Mr. Tracy would like to know what did you mean by that?” I said, “Well, at least I know someone is reading my report.” I remember one time when he was in France making The Mountain we had a series of delayed conversations because he would call one night and I would get the message the next time I saw her…[W]hen we had the first big league ball game in Los Angeles, a benefit for the Tracy Clinic at Wrigley Field, Baltimore and Chicago played the first big league game. Mr. Tracy showed up, but he showed up about the second inning, when everyone was looking straight ahead, and left about the eighth inning so there wasn’t a big spotlight on him in their box that would detract from her.

There were the tentative overtures Spence would make to become more involved with the clinic, but Louise held him at a careful distance, the clinic being the one distinct thing in their lives that she could genuinely call her own. “He felt it did absorb my life,” she said,

and it did. Once you got into it, it was so big and it was so demanding…[T]wo or three times he said, I think sincerely, “Could I learn enough about that clinic that I could go out and talk some about it?” He said that many times. “Could I?” he said. “I would like to do that.” “Well,” I said, “you have to really work, you have to have learned an awful lot—much more, you know. A lot of work goes into it. You don’t know why, you don’t understand this and that. You really have to study…[T]hey ask you questions and you can’t get up before people and not really know.” “No,” he said, “I suppose not, but you know, I’d like to do that.” [He] could never get down to all the little things about the details.

In the end, Tracy’s participation was limited to the funding he could so readily provide. “They used to call him and tell him how much it was,” Dr. Lowell said, “and he would write the check for that amount.”

In December 1960 writer-director George Seaton and a group of supporters gave a recognition dinner in Louise’s honor at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Y. Frank Freeman, the retired president and chairman of Paramount Pictures, served as chair of the sponsoring committee, which was comprised of a number of civic and business leaders, Mr. and Mrs. Justin Dart, Dr. and Mrs. Norman Topping, Leonard Firestone, Jimmy and Gloria Stewart, and Walt Disney among them. Close to one thousand guests jammed the hotel’s International Ballroom to hear keynote speaker Billy Graham, and thousands more watched the event, hosted by Robert Young, on TV. Dr. Graham gave a generic forty-minute talk on the challenges of communication, gearing his remarks to a largely Republican crowd still smarting from the narrow defeat of Richard Nixon at the polls.

When it came time for Louise to speak, her wavy hair dyed a silvery blond, she talked of the original twelve mothers at the clinic, how they made curtains and re-covered furniture while their husbands plastered the walls. “The first person I would like to mention,” she said, “is my husband. Without his interest, without his support, moral as well as financial, there would never have been a clinic.” Tracy, of course, was nowhere to be seen on the dais. “I assumed that he would be up on the front table,” said Dr. Lowell. “He had a table in the very back.” Louise gave an impassioned talk, her voice quivering at times, and was accorded a five-minute standing ovation at its conclusion. “I have never been so moved by anything in my life,” she said. Over the course of the evening she kept an eye out for Spence, who was pacing, ducking in and out of the ballroom. “Sometimes he would go to the back and you could see him in a little cubby hole there. He was embarrassed. He always said, ‘It’s your show.’ ”

As the clinic’s namesake, John Tracy was present that night, beaming out over the room even as he faced yet another challenge in a life overwhelmed by them. Having been fitted with thick glasses at the age of seven, he was diagnosed in 1940 with retinitis pigmentosa, a narrowing of the field of vision that can end in complete blindness. Apart from early problems with night vision, John functioned fairly well, driving his own car and attending classes, first at Pasadena, later at UCLA and Chouinard Art Institute. In 1952 he was hired briefly as an assistant art director when Bill Self began producing The Schlitz Playhouse of Stars. “I had an art director, Serge Krizman, and he needed some help. I said, ‘I’d like you to try John, because he’s a good artist.’ After a couple of weeks, Serge came to me and said, ‘Bill, he’s not a help, he’s a hindrance. He’s a good enough artist, but I can’t communicate with him. It’s very embarrassing.’ So I had to let John go. It was very hard to help John.”

In 1957 Walt Disney found John a job at the studio, where he was eventually put in charge of the cell library. “He did a lot of things,” said Ruthie Thompson. “He started out in the art props. He was such a nice guy. He said, ‘God put me on this earth for a purpose. I just hope I’ve fulfilled it.’ ” John left Disney when his eyesight got so bad that he could no longer drive. At the age of thirty-six he began to learn sign language. “He decided that after his eye trouble began to become pronounced,” said his mother. “He said, ‘I think maybe I would like to take some lessons.’ In the early days we were never exposed to it.”

The Devil at 4 O’Clock finished on December 29, 1960—two weeks over the guaranty period specified in Tracy’s contract. The William Morris office contended he was owed another $50,000 by Columbia Pictures, but the studio disputed the charge, pointing out that he had been sick five days on the picture. Production never stopped, however, and Tracy had worked to get rid of Sinatra, who finished two weeks ahead of schedule. After a call from Abe Lastfogel, Columbia coughed up $25,000, agreed to another $15,000, but disputed the final $10,000. “Par for the course!” said Tracy.

Stanley Kramer, meanwhile, was readying Judgment at Nuremberg for the cameras, affording Tracy a minimal six-week break between pictures. “There was so much distribution objection at United Artists to this downbeat, uncommercial subject,” Kramer said, “that the only way to get it made was with an all-star cast.” An old hand at candy-coating difficult material, Kramer loaded the first film he ever directed, Not as a Stranger, with six major names. For Judgment he loyally insisted on Tracy’s casting as Dan Haywood, even as United Artists pressured him to use Jimmy Stewart instead. “Tracy’s no lodestone,” one of the UA executives declared. “I remember listening to the conversation,” said Abby Mann, “and Kramer was upset. He said, ‘What do you mean he’s no lodestone?’ He just wouldn’t desert a friend.”

Kramer soothed the management at UA with the casting of Burt Lancaster, who, with the release of Elmer Gantry, was in line for an Oscar nomination. Artistically, he justified the move with the reasoning that Lancaster was not the “obvious choice” for the part. “His character was guilty and he was aware of it—that gave him a hook and I think he grabbed it.” The Austrian actor Maximilian Schell was retained from the TV production, and Kramer filled out the cast with Richard Widmark, Montgomery Clift, Judy Garland, and Marlene Dietrich.

Dietrich’s character provided a compelling counterpoint to the Germans on trial. “We thought there should be a woman, or a romance,” said Abby Mann,

and, at the time, Stanley said to me, “I’d like to use Paul Newman and his wife [Joanne Woodward] in the film.” He said, “Supposing [Haywood] has a daughter, and the daughter has an affair with Newman?” I tried it, but it didn’t seem to work. Then [in Berlin] I met a woman who was the widow of a general. She was talking to me about herself, and she was saying, “My husband was a soldier. I didn’t want him to be hanged, but to be shot. I wanted a soldier’s death for my husband, and I hated the Americans for not permitting it.” She said, “I’m writing a book about it,” but I could sense that she would never finish the book because she didn’t want to tell how much Germans were really involved with what happened. So I came back, and I met with Stanley in a Chinese restaurant. He said, “How’s the Newman part coming?” “Well,” I said, “you know …” And I told him about this woman. I said, “I wonder whether Dietrich might do this?” He said, “That’s a good idea!” That was the major difference between the TV version and the film. And I must say Marlene was wonderful.

Clift agreed to do the film for expenses, as Kramer needed the name value but couldn’t afford the actor’s usual salary. “Since it’s only a single scene and can be filmed in one day,” Clift told the New York Times, “I strongly disapproved of taking an astronomical salary. But in the business I felt it was more practical to do it for nothing rather than reduce my price or refuse a role I wanted to play.”

Garland was the last major figure added to the cast, having not appeared in a movie since A Star Is Born in 1955. Her part, like Clift’s, was that of a prosecution witness, but she could ill afford to play the role for free. Her deal was for a flat $35,000; Kramer made the surprising announcement in New York, garnering considerable publicity for the picture.

“We call these ‘pace-setting performances,’ ” Kramer said. “Their function is not unlike those of the runner who sets the pace in a key race for the man who is out to set a record. These are speaking roles that last up to seven minutes on the screen. They have an explosive quality—that is, a beginning, a middle, and an end—and are pertinent to the main theme. Unlike cameos, they don’t simply drop an actor in front of some scenery for the value of his name on the marquee; they utilize his talents in more than one scene and in a developing type of characterization.”

Kramer followed up with a full-page ad in the Times, committing to a December 14 premiere at Kongresshalle in Berlin, the scene of the first public screening of Inherit the Wind. Immediately following the premiere, Judgment at Nuremberg would open in the major European capitals and in reserved seat engagements in six U.S. cities, including New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The failure of The Diary of Anne Frank as a roadshow attraction didn’t faze him, and he pointed instead to the record advance that had greeted the benefit openings of Otto Preminger’s Exodus. “It’s our intent to go hard ticket, but I wouldn’t want to book 45 theaters now.” The setting of a target date (der Tag) would serve as a “tremendous psychological drive” for everyone connected with the picture.

The first reading for the cast was held on February 15, 1961, four long tables forming a square on Revue’s Stage 28, where the film’s dark-paneled courtroom interior had been erected. Originally, Kramer had wanted to shoot the film in the actual courtroom in which the trials had taken place. “We couldn’t,” he said, “because it’s still in use today. So we took measurements and carefully re-created it on the soundstage in Hollywood, although we finally had to scale down some of the dimensions for the involved camera movements. A courtroom … is a very static set. The attorneys had to be separate and distinct from the defendants and witnesses, by law. So the film becomes a ping-pong game unless you try to move the camera, which I tried—not always successfully—to do.”

The read-through was scheduled for 9:00 a.m. but was late in starting because Maximilian Schell had yet to arrive. One of several holdovers from the original Playhouse 90 production, Schell had prepared for the movie version by reading the entire forty-volume record of the Nuremberg trials.

“Eventually,” said Marshall Schlom, Kramer’s new script supervisor,

Max Schell arrived—he had gone to Western Costume for a fitting or something. When he came in, he didn’t have a script. He said, “I left it in my car.” I had a bunch of scripts, so I helped everybody out. Lancaster came in and sat down and put his glasses on and set his script in front of him. Widmark put his glasses on and had his script in front of him. Judy wasn’t there, Monty Clift wasn’t there, but Bill Shatner was there, all of the defendants, Werner Klemperer and the others, they were all there. There were probably fifteen or twenty in all. Spencer came in with his script; he put his glasses on and he opened his script. The rest of them just left it there, but he opened his script as if he wanted to check something. At that point, Stanley introduced everybody; some of the people knew each other, of course. Everybody was very respectful of Tracy, and it was all very formal. Stanley kept it that way. There was some kind of aura, a feeling we were a step above normal films, that we were doing a film that Stanley felt just had to be made.

Tracy’s part in the film, at least the portions in the courtroom, was fragmented. His part went all the way through, but for a period of time it was just “Would you speak up?” and then six pages later he would have an interjection, and that’s the way it was in the script. So he did the same thing with this reading—he would follow for a while and then he’d remember, “Oh, I think I have a cue coming up,” and he’d look at his script again. Widmark had memorized his whole part—he never opened his script. Lancaster was a gentleman, very eloquent. He sat with the script open in front of him and did it very carefully. Everybody had their own way of doing this reading, but I remember Spencer vividly because he just didn’t have much to do. His major scenes were with Marlene Dietrich; in the courtroom he only had this one speech where he read the verdict.

So Tracy was sort of like a fox that was hiding in the bushes. He played everything very low key. My first impression of him was: Gee, you’re sitting here with Spencer Tracy—you have to be impressed. But he didn’t seem to be this typical big-time actor who needed to be “on” all the time. He didn’t need to impress anybody. And that spilled over into the production, because we eventually had to get everybody into the witness box. They all had to tell their stories, they all had to have their day in court. They all had their turn being in the spotlight, and Tracy was always sitting in the background. By the time we got to Tracy’s work, which was basically the decision, all of the big stars had already had their turns. And he was lying there waiting…

In Abby Mann’s mind, the power of the screenplay depended on an actor of Tracy’s authority in the part of Judge Haywood. “Tracy was the embodiment of America in a way. You think, ‘Well, this is an ordinary guy.’ But like a lot of guys like him, he’s not ordinary.” It was as if a lifetime of careful refinement had prepared him for the role, the summation of an entire career. “Time magazine said that in Inherit the Wind I acted less and less,” Tracy said to Joe Hyams. “Isn’t that the goal? Ethel Barrymore once told me when I asked her about acting, ‘The idea is to be yourself,’ and George M. Cohan said the same thing, ‘to act less.’ I finally narrowed it down to where when I begin a part, I say to myself, ‘This is Spencer Tracy as a judge’ or ‘This is Spencer Tracy as a priest or as a lawyer,’ and let it go at that.”

That said, he bristled at the inference that he was just playing himself. “Who the hell do you want me to play?” he would thunder. “Humphrey Bogart??” And then: “An actor’s personality is, naturally, a part of his performance. Alright, so you like mine. Big deal. Thanks.”

Chester Erskine went on to explain that “what he really meant was, ‘This judge is Spencer Tracy’ or ‘This priest is Spencer Tracy’ or ‘This lawyer is Spencer Tracy.’ He had learned how to bridge the gap between the real and unreal, the objective and the subjective. He did not act, he was.” Tracy, he continued, belonged to a school of art “which believed in selection—not how much the actor could do in any given scene, but how little he had to do to make the point, the constant refinement and editing of a performance until it had reached its minimum to make the maximum, the difference between those two margins being the audience’s own emotional participation.” As John Ford once said of Tracy: “I think he could play anything that he believed in.”

Following a week of rehearsal, getting the company on its feet, Kramer began shooting Judgment at Nuremberg on Wednesday, February 22—Washington’s Birthday. Working in sequence, he completed Scenes 24 through 26 and part of 27, the first scenes to take place in the courtroom at the Palace of Justice.

“The Tribunal will arraign the defendants,” Tracy said, delivering his first lines. “The microphone will now be placed in front of the defendant Emil Hahn.” His other lines that day were equally dry, and work broke off just ahead of Dick Widmark’s opening statement, a scene that would involve some ambitious camerawork. Impassioned and letter-perfect, Widmark’s speech the next day was covered with a 360-degree pan of the camera that took in the entirety of the courtroom and its spectator mix.

“Everyone in the crew had to carry the cables and equipment around in a circle for that,” Kramer explained. “It’s the funniest thing in the world to see happen on the set. Out of the dullness of the situation I circled him in order to pick up Tracy and the judges in the shot without simply cutting. It was just something I worked out—where Widmark’s lines would occur in relation to who is seen in the background. We rehearsed a long time for that—to photograph people just at the right Widmark line.”

Throughout the tedium of the technical rehearsals, Tracy remained in place, patient and compliant. “All you can do,” he said of the inherently static nature of the action, “is play it. The big difficulty in this picture is in Mr. Kramer’s lap as a director.”

Widmark’s scene was followed by Maximilian Schell’s equally impassioned opening statement for the defense. Testimony began with Widmark’s examination of actor John Wengraf, playing Ernst Janning’s former law professor. “When we started to shoot,” said Marshall Schlom, “Tracy would come in and do the off-stage shots as well. When he was off stage, he would say, ‘Come sit next to me.’ And then he would say, ‘Nudge me when I’m supposed to say something’ because every five or six pages he had to say something like, ‘Objection sustained.’ ”

Marlene Dietrich was on hand from the beginning, observing on the stage and distributing cookies and danishes to cast and crew members, some of whom had worked with her when she made Destry Rides Again on the Universal lot in 1939. She had no substantive scenes in the courtroom; it is, rather, Mrs. Bertholt’s former house in Nuremberg that Haywood is assigned as a residence during the course of the trial. He comes upon her for the first time in the kitchen, where she is retrieving some of her belongings.

At age fifty-nine Dietrich was playing an athletic woman in her forties. “She was nice,” said Widmark, “but she used to drive Tracy crazy. He didn’t use makeup and she had to fix up to the nines. He’d go nutty waiting to do their scenes together.” Hepburn, with her father, was touring the Middle East—Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan—leaving Tracy to pass the time with Dietrich between shots. “She was very respectful,” said Marshall Schlom. “She liked being the star attraction normally, but with Tracy there she knew her place … She was a good cook, apparently, and she loved to be friendly and shmooze and laugh and be joyful. Around Tracy, though, she was much more sedate, quieter, letting him have the stage.” Dietrich would later describe Tracy in her autobiography as “the only really admirable actor with whom I worked.”

Tracy began talking of retirement again, saying another picture would be anticlimactic after Judgment at Nuremberg. He turned down Otto Preminger, who wanted him for Advise and Consent, and was also said to have been Harper Lee’s choice for Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. Bob Yager remembered a telling remark that Tracy made to photographer Phil Stern, who was shooting The Devil at 4 O’Clock in Hawaii for Globe Photo. Stern had taken some pictures of Tracy—portraits—and when he showed him the prints he said, “I think they’re very, very good character shots of you.” Tracy examined the images impassively. “When you get to my age,” he said, “it is hard to say when a picture is a wonderful character study or when it’s just a picture of an old man.”

As expected, he drew another Oscar nomination for Inherit the Wind, even as Fredric March, another two-time winner, was shut out of the running. Tracy was clearly pained by the omission, even as he sought to distance himself from the proceedings. “I have to admit to you—Freddy—that I am wondering a bit if maybe the votes were tabulated in Cook County…,” he wrote in acknowledging his costar’s gracious wire of congratulations. “But I thank you—a good Democrat—for giving me the benefit of the doubt—and how I miss you in the daily entanglements of Stanley Kramer’s camera moves.”

To press such as Pete Martin or Joe Hyams, Tracy rarely missed an opportunity to alienate the voting membership of the academy. “I care about a great many things,” he told Martin, “but I sure as hell don’t give a fiddler’s damn about the Academy Awards, and I was honest from the beginning. I never did. When I was winning it, and when I was nominated a great many times.”

Nor did he buy Martin’s suggestion that a nomination somehow brought paying customers to see an otherwise underperforming film. “I was nominated for Old Man and the Sea,” he said, “which grossed fifteen dollars, seven of which they found in the aisle. I was nominated for Bad Day at Black Rock, which was not a success at the box office. It has nothing whatever to do with it. Maybe the awards, but the actors nominate. And the actors nominate if they think you give a good performance. What the hell has the picture got to do with it? Nothing. Not a goddamn thing.”

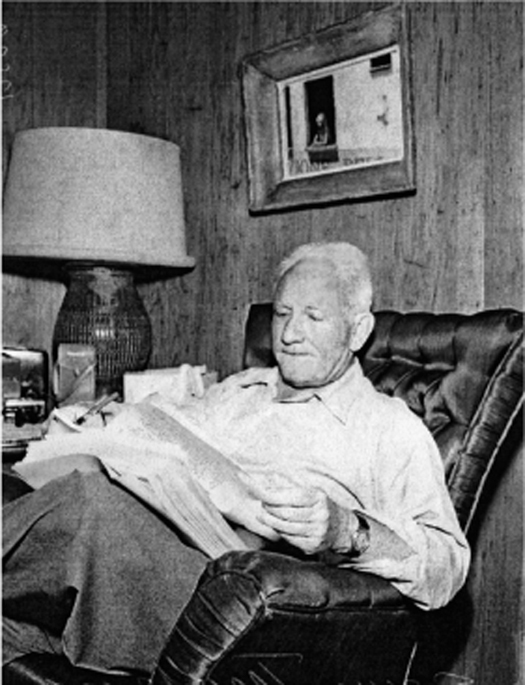

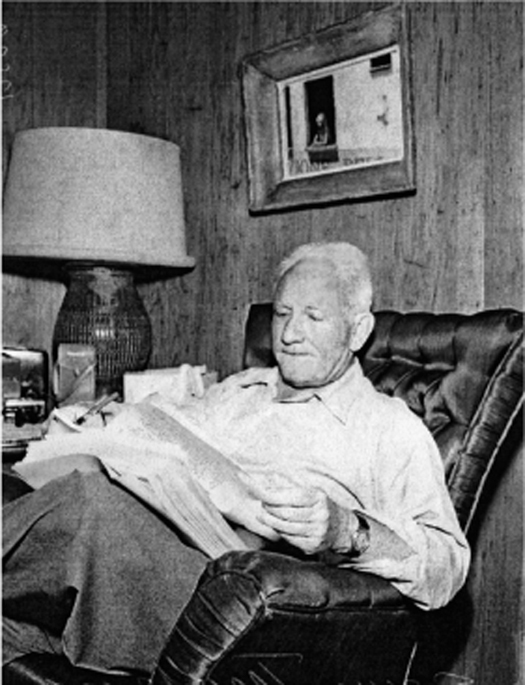

Tracy in his rented home on the George Cukor estate. The chair was an old horsehair rocker that Hepburn had reupholstered. (HEARST COLLECTION, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA)

Nevertheless, Columbia pulled The Devil at 4 O’Clock from its scheduled summer release, spotting it instead for the fall, presumably in the belief that by now any Tracy performance, regardless of the material behind it, merited a nomination.

Montgomery Clift paced the floor of his room at the Hotel Bel-Air, struggling for words. “I can’t really answer you honestly,” he said. “I was offered $300,000 for another role. That would have been the highest per diem ever paid. But what I did, I don’t consider it—what’s the word? I knew it yesterday … altruistic. It’s not altruistic on my part. People milk pictures, and I felt for this role which was to be shot in four days … Why did I do it? I really don’t know.”

He was speaking to a writer for the Los Angeles Times who had asked him why he had chosen to make Judgment at Nuremberg for nothing. “Maybe you can tell me,” Clift said to the man. “You look brighter.” The Times’ Don Alpert suggested that perhaps he just wanted to. “I feel so embarrassed,” the actor responded. “I really feel embarrassed. Nobody understands that. I wanted to play it. Deeply. As in D-E-E-P-P-P-L-L-L-L-Y. But you see, that’s so far from the conscience of people here. They think it has to be for publicity or something.”

Clift was still embarrassed when he arrived on the Revue lot, sporting a “very bad haircut” because he believed the awkward man he was to play, Petersen, would have gotten a special haircut before testifying against war criminals.

“Monty Clift came in at nine o’clock,” Marshall Schlom recalled,

and there was a hush on the set. What a troubled man he was. And all of us knew that. He was very nice, but you could tell he was frail. He was a shell of what he used to be. He came in and Stanley shook his hand—there were warm welcomes—and he sat him down in the witness box. Monty had a thermos, which we all figured was coffee. We started to do some lighting, and Stanley was talking to him, and then Stanley walked away. Clift opened up the thermos and poured … and it wasn’t dark liquid. It was liquor; it was a sidecar (which I found out later). He poured this into the lid of the thermos, and he held it for a second and looked at it. And then he felt three hundred pairs of eyes on him. He looked up and he looked around at all of us watching him, and he said, “Fellows, I’m sorry. I need this.” It tore our hearts out.

Clift’s scene was the testimony of a man sterilized by the Nazis because he was deemed “mentally incompetent.” Widmark’s examination concerned the events leading up to the procedure, including a 1933 attack on the family. “Some S.A. men broke into our house,” Clift recounted. “They broke the windows and doors. They called us traitors and tried to attack my father.” Widmark delved into the examination that stemmed from Petersen’s later application for a driver’s license, Kramer’s camera circling Clift to show the entirety of the courtroom, the faces of the listeners—Tracy, Widmark, Schell, Lancaster.

“They asked me, ‘When was Adolf Hitler and Dr. Goebbels born?’ ”

“What was your reply?”

“I told them I didn’t know, and I didn’t care either.”

His uncertain response to the laughter in the room is to smile weakly, his wide childlike eyes darting to all sides.

“Montgomery Clift was at a very, very low point in his life at this time,” Widmark said. “He was drinking a lot. I think he was on dope. And after twelve o’clock you couldn’t use Monty … he’d have to go home, he was out of it. But I remember, especially one morning, I was the lawyer interviewing Monty and he couldn’t make it, he couldn’t remember, he couldn’t put two and two together, and he was just a total mess. And Tracy just said, ‘Talk to me. Play it to me, Monty. Just look at me and play it to me.’ You know, he was like a pop, you know, real, sweet, nice pop. And Monty kind of…‘Okay.’ And he played it to Spence and it came out great.” Said Kramer: “Spencer was the greatest reactor in the business. Monty did play to him, and the words poured out of his mouth—the results were shattering.”1

On the set of Judgment at Nuremberg. Left to right: Richard Widmark, Tracy, Montgomery Clift, and Burt Lancaster. (PATRICIA MAHON COLLECTION)

There was trouble in Schell’s cross-examination, when his character, Rolfe, asks Petersen a simple question the Health Court always asked: Form a sentence from the words “hare,” “hunter,” “field.” Petersen’s grappling with the question prompts a meltdown, one of the most difficult scenes in the entire picture.

“This happened on a Thursday,” Marshall Schlom remembered.

Friday, we went to dailies, and Stanley wasn’t happy with them. He invited Monty to come in and look at them, and he agreed that it wasn’t what it should be. I got a call on Saturday morning from Monty Clift. He said, “Monday, I’m going to do my part over again. Can you give me an exact copy of what I said? I want to do the same words, and I want to know exactly what I said. Can you furnish me that on paper?” I said, “Okay.” So I made a hasty call to the cutter and said that I needed to come in and transcribe exactly what was on film. Monty said, “Would you send it to my hotel?” I did what he asked for, and I sent it to him by courier … and Monday morning he came back in and he re-did it and it was a different performance.

Carefully, Clift adjusted his dialogue, scratching out Mann’s fussy stage directions and reconfiguring his lines to make them more disjointed—not complete sentences but rather bursts of painful memory, irrationally arranged. “He was bound and determined to do a better job,” said Schlom, “and he was so emotional. He was a real basket case. I think nothing Stanley or maybe even Tracy could have said to him would have calmed him down. Fidgeting, fidgeting, forever fidgeting. I was rather new to movies at the time, especially big-time movies, and I was nervous for him too.”

It was torturous to watch Clift as he worked his way through the scene that day, but all the anguish ultimately proved to be worth it. “It was marvelous,” said Widmark.

Judy Garland brought her own circuslike atmosphere to the set, arriving early and drawing applause from the cast and crew. “I wanted Julie Harris for the part,” Kramer remembered. “I was about to start dealing for Julie when I opened the newspaper that night. There was an item in it about Judy Garland. I even forget the item. But I said to myself, ‘Stanley, what’s the matter with you? Judy Garland is the actress you want. She knows the suffering I want.’ ”

Garland was cast as Irene Hoffman, a woman who was sent to prison for having an affair with a sixty-five-year-old man who was Jewish, a part played on television by the Czechoslovakian actress Marketa Kimbrell. Garland reportedly worked weeks with a coach to perfect a slight German accent, and her tearful testimony was as gut-wrenching as Clift’s. When she completed her five-minute scene, there was again applause.

“It’s a cliché come true,” wrote columnist Sidney Skolsky. “I never believed it before, always smiled when I heard about it. Now I was seeing it with my own eyes. Everybody—Tracy, Lancaster, Widmark, Schell, Kramer, the extras, applauded. When I say everybody, I’m including me.” Said Richard Widmark: “It meant a lot to her. It was therapy and it gave her great confidence.”

“Wasn’t that a performance!” Tracy marveled. “I don’t object to playing stooge to Judy. She’s a great actress, eh? You know, in all the years Judy and I have been together at M-G-M we never did a movie together. I guess Judy was eleven or twelve when I first arrived at Metro.” Mickey Rooney made his way onto the set, prompting a frenzy of activity with photographers from as far away as West Germany, where there was intense interest in the film and its subject matter. “Mickey knew Stanley,” said Marshall Schlom, “but he had to come in to say hello to Tracy and Judy, and the three of them hugged each other. The photographers went crazy, and it almost brought tears to your eyes. In context, it was just wonderful.”

It is Rolfe’s badgering of the witness that prompts Janning, the most prominent of the defendants, to break his self-imposed silence. (“Are you going to do this again?”) Said Lancaster, “I am almost a symbol of the dilemma in Germany during the Nazi period. I am the man of good intention who did things of which he did not approve. I am a man who once had a reputation for integrity and honesty; a concern for the law. But I am cynical about this trial. I doubt the ability of the judges. I am a man who has, in a sense, retreated into another world. At the same time I must not be a man in a cataleptic state. I must become involved in the trial.”

Tracy, who never ceased chiding Lancaster over his billing and his compensation, had become so fixated on Lancaster’s appearance in the picture that his scenes on the stand were the only ones he specifically noted in his datebook. “Lancaster, who was a wonderful actor and a wonderful man, was miscast,” said Abby Mann. “Olivier wanted to do it originally, and Stanley and I went to talk to him about it. He had a very interesting grasp of it. But he was courting his soon-to-be wife, and he didn’t want to play an older guy. At least that was part of what he said. As a matter of fact, a lot of people liked Burt in it, but I didn’t, and neither did Stanley eventually.”

Tracy’s twitting of Lancaster may also have had something to do with the fact that Lancaster had been nominated for an Academy Award for his work in Elmer Gantry—and that he was the odds-on favorite to win. (The other nominees for Best Actor were Trevor Howard for Sons and Lovers, Jack Lemmon for The Apartment, and Olivier for The Entertainer.) When Lancaster, in fact, did win the award on the night of April 17, he thanked even “those who voted against me” and was careful to bring the statuette onto the set at Universal City the next morning so that he could show it to Tracy. A week later, Tracy committed to playing General William T. Sherman in How the West Was Won, an all-star western to be directed, in part, by John Ford.

As the various cast members completed their big scenes, attention fell naturally to Tracy as he prepared to deliver the verdict of the tribunal. Dietrich was often with him in photographs taken on the set, sleek in black slacks and top, welcoming his visitors, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas among them. “We laughed a lot together since his sense of humor was like mine,” Dietrich said. On the night they filmed a walk through the rubble of Nuremberg, standing sets on the back lot dressed to suggest bolstered landmarks still erect after the ravages of war, she brought apple strudel for the crew and could be observed huddling with Tracy as they sipped hot chocolate. “You’re really not my type,” he’d tell her. “You’re Continental; I’m just an old fart.” (They were, in reality, a mere twenty months apart in age.) “Spencer Tracy was a very lonely man,” Dietrich concluded, “or so he seemed to me.”

The morning of the verdict began like most others, the courtroom packed with extras and the principal cast members (Dietrich, this time, included). The core of the scene had timed out at six minutes, the rest—the entry of the judges, the passing of the sentences, the dissenting opinion of Judge Ives (Ray Teal)—brought it to approximately nine minutes, uncomfortably close to the capacity of a single film magazine. “During rehearsals,” said Kramer, “Spence commented on the length of the speech and wondered if there were some way in which he could do it all the way through. We thought about it and finally came up with the solution that worked.”

Following the film’s completion, Kramer, with a publicist’s zeal, gave the length of the speech as thirteen minutes and fourteen seconds and claimed that he had used two cameras to capture it—one starting at the beginning, the other starting at the seven-minute mark. Marshall Schlom remembered it differently: “Stanley had asked me to get the verdict, type it, capital letters, triple-spaced. He had told me, ‘I’m going to take your typed verdict, I’m going to put it in a folder, and I’m going to tell him just to read it.’ I was standing there when he went up to Tracy and said, ‘Spencer, here’s your folder. You can bring it in with you. Just open it up, and all you have to do is read it. Marshall has typed it out, it’s in capital letters, it’s triple-spaced. You shouldn’t have any problems with it.’ Tracy said, ‘Okay.’ He had no intention of doing that, not one. But we had no inkling of that.”

Tracy entered with the folder in hand, sat, opened it, and, without looking down, began to speak:

The trial conducted before this Tribunal began over eight months ago. The record of evidence is more than 10,000 pages long and final arguments of counsel have been concluded. Simple murders and atrocities do not constitute the gravamen of the charges in this indictment. Rather, the charge is that of conscious participation … in a nationwide government-organized system of cruelty and injustice in violation of every moral and legal principle known to all civilized nations…

As he spoke of the evidence, how it supported the charges against the defendants and how the “real complaining party” at the bar was civilization, Kramer’s camera trucked slowly to the right, catching the back of Lancaster’s head in the prisoners’ dock.

Men who sat in black robes in judgment of other men. Men who took part in the enactment of laws and decrees the purpose of which was the extermination of human beings. Men who, in executive positions, actively participated in the enforcement of these laws—illegal under even German law.

He spoke of Janning as a tragic figure. “We believe he loathed the evil he did.” Yet compassion for “the present torture of his soul” should not “beget forgetfulness of the torture and the death of millions by the government of which he was part.” He spoke also of how the trial had shown that “under a national crisis” ordinary and even “able and extraordinary men” could delude themselves into the commission of crimes “so vast and heinous that they beggar the imagination.”

Marshall Schlom recalled looking over at Kramer and seeing that he was “getting a little itchy” as the scene progressed. “I think he was a bit worried that maybe Tracy wasn’t going to finish before the camera ran out of film.” Tracy continued, his voice at times betraying the emotional weight of the words he was saying.

No one who has sat through the trial can ever forget them. Men sterilized because of political belief … A mockery made of friendship and faith … The murder of children … How easily it can happen … There are those in our own country, too, who today speak of the protection of country, of survival. A decision must be made in the life of every nation at the very moment when the grasp of the enemy is at its throat. Then it seems that the only way to survive is to use the means of the enemy, to rest survival upon what is expedient, to look the other way … Only the answer to that is: Survival as what? A country isn’t a rock … it’s not an extension of one’s self—it’s what it stands for. It’s what it stands for when standing for something is the most difficult…

Before the people of the world … let it now be noted … that here in our decision, this is what we stand for: Justice … Truth … and the value of a single human being.

Facing the four defendants in the dock, he then proceeded to pass life sentences on Emil Hahn, on Friedrich Hoffstetter, on Werner Lammpe, and, finally, and with difficulty, on Ernst Janning.

“Tracy didn’t read it,” said Marshall Schlom. “Tracy had memorized this whole thing, which was ten minutes long. It was one reel of raw stock going through the camera. He did the wider shot first, take one, which was a print, and then we did his close-up, and take one, and it was a print. And he was just as sly as a fox, because now he had his day in court. He had trumped all the other suits, and it was wonderful to see because he didn’t make anything out of it. But he was lying in wait, he was gonna get everybody. Of course, each one of these people on the stand had done their part, and, sporadically, there had been some applause. But when it got to Tracy, everybody—the entire crew and cast and two hundred extras—were sitting and watching this and when he did take one, letter perfect, without reading it, the applause was thunderous.”

When Kramer felt he had everything he needed—well before noontime—he wrapped the company for the day. “Let’s all go to lunch,” he said, “and then we can go home.” It was at that point that Burt Lancaster approached Tracy. “How did you do that so easily?” he asked.

Tracy took the question in stride. “You practice for thirty-five years,” he said quietly.

When Judgment at Nuremberg finished in California on May 4, 1961, Kramer still had a week’s worth of location work to do in Germany. Tracy wasn’t happy about going. (“He urgently didn’t want to do that,” said Philip Langner.) Then Kate said that she would go along, and the plan suddenly became more feasible. Tracy flew to New York on May 7—“loaded,” he later wrote in his book—and was met at the airport by Hepburn, who, according to Dorothy Kilgallen, “almost conked a cameraman when he focused his lens at the reunion.” In town, she registered him at the Plaza Hotel, a curious event witnessed, coincidentally, by their friend Bill Self.

“I was with a friend of mine,” Self recalled, “and I said to my friend, ‘If Kate’s here, chances are Spence is here.’ So we went around to the back of the Plaza where the elevator is, and I saw Spence over in the corner with his collar up and his hat pulled down, standing in the shadows.” Their eyes met, but Self, who hadn’t seen Tracy in years, kept his distance. “My friend said, ‘Oh, there’s Spencer Tracy. Go say hello to him.’ I said, ‘I wouldn’t go near him with a ten-foot pole.’ He said, ‘You’re kidding. I thought you knew him.’ I said, ‘I do know him, but he’s hiding, and I’m not going to reveal his hiding place.’ I wouldn’t go near him … I never said a word to him, never acknowledged him or anything.”

Tracy boarded a Lufthansa flight to Frankfurt on the evening of May 9, arriving in Germany the next morning, again, as he noted in his book, “loaded.” The five-hour drive to Nuremberg was followed by a day’s rest, after which he and Kramer and his crew got to work, capturing street scenes and generally opening the picture up as much as possible. On the sixteenth the company moved to Berlin, where a press conference took place. Additional exteriors finished the picture on May 20, exactly on schedule. The same day, Tracy received Roderick Mann, film columnist for the Sunday Express, in his suite at the Berlin Hilton. Sipping coffee, he told Mann that he had just been reading a piece on Gary Cooper, who had died of cancer the previous week: Was he really an actor? Or just a personality?

“What a bore those arguments have become,” he moaned. “I thought Cooper was great. I hardly knew him, but I always admired him. What could he have done better in a film like High Noon? Played it with a broken arm or an accent? Cooper used to be very proud because John Barrymore once said of him: ‘He never makes a wrong move on the screen.’ The truth is Cooper hardly ever made any move. He didn’t have to, he was so good … I remember Garson Kanin, the playwright, once asking me what I thought was the most important thing about acting. ‘Learning the blasted lines,’ I said. Another time someone asked me what was the first thing I looked for in a script. ‘Days off,’ I said.”

He finished his coffee and carefully put the cup down on the table. “I never watch my old movies on TV,” he continued. “Or any old movies, come to that. Too many of my friends are dead. I don’t want to be reminded. How can I watch an old Bogart film? Bogie was a friend of mine. I saw a lot of him before he died. I can’t watch him now; I switch the set off. In Hollywood, where you’re dead you’re very dead. Sometimes you’re even dead before you’re dead. They’re always happy to give you a boost on the way. Like that special Academy Award for Gary Cooper. Until they did that nobody even knew he was ill. Why couldn’t they have left him alone? Bogie, Gable … now Cooper. All my contemporaries are going. Who knows? Maybe it’ll be my turn to bat next.”

With Judgment at Nuremberg out of the way, Tracy and Hepburn returned to Frankfurt, where they spent two days driving along the Rhine and taking in the countryside. From there they traveled to Paris, an eight-hour trip, stopping once again at the Raphael and meeting up with the Kanins for dinner. The next two weeks were idyllic—rising early, walking the city, eating elaborately. A toothache put an end to it all on June 10, complicating Tracy’s last days in the city with dental appointments. They boarded the Queen Elizabeth in Cherbourg on the fifteenth, taking adjoining staterooms for a five-day voyage that was foggy and unusually rough. (When advised, upon arrival, of the proximity of his frequent costar, Tracy feigned surprise: “If she’s on the ship I wouldn’t know it.”) In New York he was trapped by autograph seekers at Fiftieth and Park Avenue, had dinner with Abe Lastfogel, went to Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and bought a new Lincoln Continental to take back to Louise. He tooled out of Manhattan on the morning of the twenty-ninth, passing through Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Missouri, stopping at motels along the way.

The black car with the creamy interior was completely unexpected, though Tracy often impulsively bought things for his wife. (“Weeze, I thought you’d like that.”) Usually he gave her jewelry; occasionally paintings. “He said once, ‘Let’s go over and look at these pictures’ in some man’s house,” she remembered. “We went over and he had some very nice things. There was this darling little Grandma Moses and he said, ‘Wouldn’t you like this?’ Well, he got it right there.” He once bought her a Paul Clemens oil in much the same manner. “He would pop up with things.”

Tracy was still making his way across the country when Abby Mann viewed a rough cut of Judgment at Nuremberg. A letter was awaiting him when he returned to St. Ives: “Every writer ought to have the experience of having Spencer Tracy do his lines. There is nothing in the world quite like it. You are, in a way, the Chekhov among actors. Your work is honest, clean, simple, and enormously meaningful.”

Gratified, Tracy responded via his favorite mode of communication, a telegram:

AFTER FINISHING NUREMBERG THE HARD WAY DRIVING ACROSS THE COUNTRY I FOUND YOUR OVERWHELMING MESSAGE. ALL I CAN SAY AFTER READING IT IS IF THE LIGHTS GO NOW I STILL WIN. PLEASE DO NOT FORGET IT WAS A GREAT PRIVILEGE TO SAY THOSE WORDS.

With the general euphoria that attended the completion of Judgment at Nuremberg, it was easy to forget that The Devil at 4 O’Clock was still in production. The effects work—primarily the volcanic eruption at the film’s conclusion—took months to complete. (The island miniature alone took four months to build.) Then in July, just as Tracy was arriving back in Los Angeles, a camera crew was hastily dispatched to Hilo to shoot the eruption of Kilauea on the Big Island of Hawaii. (An extra crew had been stationed at Kilauea during the film’s location work on Maui, but nothing had happened.) Minus its final pieces, the picture was previewed on July 13, where 354 out of 385 cards rated it either good or excellent. Emboldened by a second, equally successful preview in Pasadena, Columbia set a budget of $1,700,000 for global advertising and promotion, prompted, in part, by the record business being done by The Guns of Navarone. Cosponsoring with Squibb, the studio committed to a month of ABC’s Evening Report—a buy alone valued at $100,000—and set mid-October openings for the picture at New York’s Criterion Theatre and the Stanley Warner in Beverly Hills. At a negative cost of $5,721,786, The Devil at 4 O’Clock was the most expensive picture Columbia had ever made.

Hepburn, meanwhile, had committed to one of the most demanding roles she would ever tackle, that of the drug-addled Mary Tyrone in Ely Landau’s production of A Long Day’s Journey into Night. Director Sidney Lumet wanted Tracy to play Mary’s husband James, a role modeled on the author’s own father, but Tracy resisted the suggestion, even when Kate thought that he might be talked into it.

“Look,” Tracy said to Lumet, “Kate’s the lunatic, she’s the one who goes off and appears at Stratford in Shakespeare—Much Ado, all that stuff. I don’t believe in that nonsense—I’m a movie actor. She’s always doing these things for no money! Here you are with twenty-five thousand each for Long Day’s Journey—crazy! I read it last night, and it’s the best play I ever read. I promise you this: If you offered me this part for five-hundred thousand and somebody else offered me another part for five-hundred thousand, I’d take this!”

Kate exclaimed, “There he goes! No! It’s not going to work!” and the three proceeded to have what Lumet later remembered as “a charming breakfast.”

While Hepburn went off to make the film in New York, Tracy remained in Los Angeles, watching television and weighing offers he had little interest in accepting. He had agreed to play Pontius Pilate in George Stevens’ much-delayed version of Fulton Oursler’s best-selling novel, The Greatest Story Ever Told, but it was an all-star affair, a “cut rate deal” as he described it. There was also talk of him doing The Leopard in Sicily for Luchino Visconti, but the choice had been somewhat forced on Visconti by Fox, which had specified one of four American box office stars as a condition of financing the film. (Gregory Peck, Anthony Quinn, and Burt Lancaster were the others.) Although he agreed to read the script, Tracy balked at spending five months on location or submitting to an interview with the director, and Lancaster wound up playing the part of the autocratic Prince Salina. Tracy was, in fact, settling into a pattern where he would work only for certain directors—Ford, Stevens, Stanley Kramer—and otherwise considered himself retired. That he was soon to be seen in two of the biggest films of the year scarcely seemed to matter, and he and Kate spent much of the remainder of the year apart.

The Devil at 4 O’Clock, though generally received as the superficial product it was, turned out to be Tracy’s biggest commercial success since Father of the Bride, with gross receipts amounting to $4,555,000. As an element of commerce, however, it lost more money than Inherit the Wind and Plymouth Adventure combined. Tracy made no comment on the fate of the picture, and his relationship with Sinatra seemed to survive the ordeal. Judgment at Nuremberg was the greater concern, and Kramer held firm to his plan for a December premiere in Berlin, despite an increasingly tense political climate that in August saw the closing of the border between East and West Berlin and the construction of a wall to prevent defections to the West.

“I wanted Spencer to go to Berlin for the world premiere,” Kramer recalled, “and Kate didn’t want him to go. I said, ‘How can you tell him not to go? The trip wouldn’t hurt him, and you said you’d go with him.’ She replied, ‘It seems such a stupid thing to do. What do you want to flaunt him in front of the Germans for?’ I said, ‘I’m not flaunting him. Willy Brandt’s invited us. Let’s go.’ She was reluctant, but finally she agreed.” Kramer had not seen Tracy and Hepburn together much—she was mainly out of town when Inherit the Wind and Judgment at Nuremberg were made. “As soon as [they arrived in Berlin,] she got him set up in his place with all the pill bottles and everything, and all the prescriptions, and then took off his shoes and put on his slippers, and put his robe around his shoulders. She was like a nursemaid, really.”

More than three hundred newsmen from twenty-six countries had traveled to the partitioned city to cover the event, some 120 columnists and political commentators alone having been flown in via charter from New York. Tracy, as the film’s principal star, was closely questioned by reporters at a press conference. Did he believe every word he said in the script? “Yes.” Why did he take a role like this at this stage of his career? “Money.” (“Gelt!” an interpreter shouted in German.) To most questions he answered simply yes or no. Finally one journalist, apparently irked, asked, “Do you always answer just yes or no?”

“No!” he shot back.

Even with Tracy, Montgomery Clift, Maximilian Schell, Richard Widmark, and Judy Garland in attendance, the premiere was pretty much a bust. Tracy grew ill and left the Kongresshalle—just seven hundred yards from the Berlin wall—shortly after the film began. (A UA representative later explained it as a “flareup of an old kidney ailment.”) Most of the Germans attending the champagne dinner afterward were poker-faced, some thinking the film badly timed given the country’s division.

“There was a buffet for fifteen-hundred people,” Kramer recalled, “and only two-hundred showed. I had been raised to know that the perfect tribute at the end of a film was like at the end of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address—total silence. We had total silence, but I knew it wasn’t a perfect tribute. The press was very divided, some saying that all the Germans should see the film if they aspired to be a cosmopolitan city in Berlin again, others saying it’s just raking over old coals for what?”

At the Berlin premiere of Judgment at Nuremberg. Left to right: Tracy, Montgomery Clift, Judy Garland, and Stanley Kramer. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Many felt the film too long, but Friedrich Luft, a German theater critic, found it a “fair and human statement” of the problems of responsibility and guilt for war crimes. “I think people in Germany will accept it.” Conversely, Wolfgang Will, who reviewed the picture for the West Berlin tabloid BZ, thought it went much too easy on the Nazis. “This is a fable of Nuremberg, a downright counterfeit,” he wrote. “Much worse things happened at those trials than what was portrayed.” According to a report in the Los Angeles Times, four German papers praised the film, one condemned it, and a sixth was noncommittal.

Tracy and Hepburn departed for Paris via chauffeured limousine, only to be denied access to the Autobahn that crossed East Germany because Tracy lacked a visa. The car detoured back to East Berlin, a distance of thirty-eight miles, to comply with the requirement, and they weren’t finally ensconced at the Raphael until well past dark. Continuing on to Le Havre, Tracy boarded the liner United States for New York, leaving Hepburn to catch a flight to London.

In Los Angeles, the West Coast premiere of Judgment at Nuremberg was a benefit for John Tracy Clinic, with George Cukor, Walt Disney, Burt Lancaster, Ronald Reagan, Dinah Shore, and Robert Young listed among the twenty-five members of the ticket sales committee. With seats selling for twenty-five and fifty dollars each and former Vice President Richard Nixon heading the guest list, the sold-out event raised $50,000 for the clinic. Louise, escorted by John, hosted a champagne reception in the theater’s lobby after the film and spoke briefly of the clinic’s work: “It is a place where parents of deaf babies and young children may come for encouragement and guidance to help their children.”

The trade reviews, which appeared in October, were admiring and respectful, even as the film’s length and top-heavy casting—for which Abby Mann later took some of the blame—were called into question. As the Variety review stated from the top: “The reservations one may entertain with regard to Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg must be tempered with appreciation of the film’s intrinsic value as a work of historical significance and timeless philosophical merit. With the most painful pages of modern history as its bitter basis, Abby Mann’s intelligent, thought-provoking screenplay is a grim reminder of man’s responsibility to denounce grave evils of which he is aware. The lesson is carefully, tastefully, and upliftingly told via Kramer’s large-scale production.”

Internationally, the film was playing in thirty-six cities by Christmas of 1961. However, with its initial U.S. engagements limited to New York, Los Angeles, and Miami Beach, most Americans learned of the movie through the national magazines, many of which gave Kramer and the picture full marks for intent and delivery. Henry Luce’s Time (which in 1939 had named Hitler “Man of the Year”) was an exception, accusing Kramer of cynically timing the release of his movie to coincide with the reading of the verdict against Adolf Eichmann. In Show, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., pondered the extent to which movies could serve as a medium for the intelligent discussion of complicated problems and pronounced the film brilliant but confused. “It has the raw force of an eloquent pamphlet without clear direction or logical conclusion.”

Unfortunately, one of the film’s key showcases, with more than seven million readers, was in the pages of Look, where Tracy’s 1960 interview with Bill Davidson, killed after the failed release of Inherit the Wind, was raised from the dead and reslotted for the magazine’s January 30 issue.

“I had a friend—I went to Marquette with him—named Jerry Zimmermann,” Frank Tracy said.

[H]e was an associate editor at Look. Well, he did a lot of traveling. And, [since] he and his wife were from Milwaukee, they used to get back and forth. Whenever he came through town he’d call me; we’d have lunch or dinner, a drink, or something. He came through one day about 1960 or so, and he said, “Do you know Bill Davidson?” I said, “No, I never heard of him. Who is he?” He said, “He works for Look. He’s a full-time, part-time kind of guy, but he’s on the payroll. I see him from time to time. We share information on stories we’re doing and so on. He told me he’s doing a piece for Look on Spencer Tracy.” I said, “Oh yeah?” Nodded. “It’s going to be a Spencer Tracy–Katharine Hepburn story.” I said, “Ohhh.” He said, “I’ve not seen it, but he’s talked to me about it. The Tracy family ain’t gonna like this.” I said, “Would it do any good—should I talk to him?” He said, “Oh Christ, no, don’t talk to him. He’s a bastard. He’d be all over you, he’ll never let go of you. He’d follow you to your grave. He has a technique of making something serious or horrible … he develops things that way. Everything he’s ever written is written in that vein. He’s a real son of a bitch. You want to stay away from him. But I just thought I’d let you know that this is coming. It ain’t gonna be good. I think it’s a series. Brace yourself. This is going to be a firecracker.” So I called Carroll. They knew about it, they knew something was in the works. I got the impression that Carroll didn’t understand that it was going to involve Hepburn, because he kind of said, “Ohhh.” Something like that.

“In 1960,” recalled Eddie Lawrence, “I was back [in New York] and I went up to see Katharine, you know, just as a courtesy to see her, and she was really quite disturbed. Tracy was going to do a cover story for Look, and Katharine said, ‘I just feel worried that they’re going to use the story about Spencer and me.’ I said, ‘Look, if [editorial director] Dan Mich, as you tell me, has agreed that Spence has rights to look at the story, you don’t have a thing to worry about. He’s not going to break it. It’s unusual in the first place that Look would ever let you see the story.’ ”

Bill Davidson and Look had parted company over the writer’s outside assignments and his practice of inflating expense reports. By the fall of 1960, his name was gone from the masthead as a contributing editor and he was working at McCall’s. Warned by Pete Martin that Davidson was “a sneering son of a bitch,” Tracy sailed for England with Hepburn just after Christmas 1961, the ship carrying Noël Coward, Victor Mature, and Sir Ralph Richardson and his wife among its 122 first-class passengers. When Look hit the stands a month later, readers were surprised by the relentlessly negative tone of the piece.

“At 61,” the profile began, “Spencer Tracy is ornery, cantankerous, sometimes overbearing, sometimes thoughtless. He is a rebel, a loner, a man of mystery who occasionally disappears for weeks at a time. Little of his behavior has been reported in newspapers. Yet he has been the object of nationwide hunts by his studios. During his appearance in more than a hundred plays and films, he has led an unorthodox private life, has staged violent revolts against his producers and directors, and wrecked studio sets.”

Davidson went on to sketch Tracy’s early life, largely drawing the details from clipping files and studio-compiled bios. Tracy’s discovery of John’s deafness was misportrayed, and most of the revelatory statements in the piece were attributed to conveniently anonymous sources. One “friend” explained how Tracy’s drive to help his son “overcome his handicap” increased his natural tendency to escape his problems and contributed to his “roistering” in Hollywood. “John’s deafness also helped bring Spence and Louise together,” the friend continued, “but, paradoxically enough, it set up a situation that drove them apart and led him to seek the companionship of Katharine Hepburn.”

John Tracy subscribed to Look, but Louise saw the article first. “John doesn’t need to see this,” she said to Susie, and the rest of the week was spent deflecting questions of how the issue could have gone astray. (Susie herself chose not to read it.) Eddie Lawrence was surprised at how Dan Mich had apparently reneged on his pledge to let Tracy see the article, perhaps having forgotten their original bargain in the two years it took to get the piece into print. “Of course,” he said, “you can never trust ’em anyhow.”

Davidson later claimed that Tracy had talked openly of his relationship with Hepburn during their 1960 interview (speaking of her as “Kate, my Kate”), but publicist Pat Newcomb, who Davidson said was present at the meeting, had absolutely no memory of such an exchange. (Newcomb met Tracy through R. J. Wagner and Natalie Wood but said that Tracy never spoke of Hepburn in front of her, either privately or in an interview.) Joe Hyams saw a more basic distinction: “We were local reporters [unlike Davidson] and, of course, we knew that Rock Hudson was gay and things like that, but we’d have never written about it. He was a national reporter; maybe that’s why he did it. For us, that would have been a betrayal. We could have lost all our contacts. So it never occurred to me to write about Tracy and Hepburn.”

On a more positive note, Tracy received his eighth Academy Award nomination for Judgment at Nuremberg but ended up losing to Maximilian Schell, who, in his acceptance speech, praised the picture, its director, and the other members of the cast, “especially that grand old man, Spencer Tracy.” Tracy called him and said, “You son of a bitch! I don’t mind you winning the award, but calling me the grand old man, as if I’m some sort of ancient monument, is just too much!”

The film itself was wildly successful as a two-a-day roadshow attraction, playing sellout houses for months in New York and Los Angeles and drawing heavily in cities like Washington and Toronto. As was frequently the case with highbrow entertainment, though, the film never caught on in general release, where its extreme length limited the number of showings a theater could manage. Produced on a budget of $3,170,000, Judgment at Nuremberg recorded a domestic gross of approximately $4 million and extended a near-perfect record of losses for Stanley Kramer at United Artists.

1 Despite his early work with the Group Theatre, Montgomery Clift did not consider himself a Method actor. His technique, in fact, was remarkably similar to Tracy’s, although Clift was not the quick study that Tracy happened to be. Described by Lee Strasberg as the “perfect Method actor” because he came by it naturally, Tracy thought Stanislavsky’s emotional or “sense memory” technique, when misapplied, encouraged overacting—the doing of more than was necessary. Method actors, he felt, sometimes obscured the meaning of the text in the crafting of a performance. “If I remember correctly,” said Chester Erskine, “he said, ‘They don’t let it breathe.’ ”