1

Kyo and Jitsu

W. IS A SERIOUS ALCOHOLIC. He’s been downing a bottle of wine almost every day since he was seventeen. Now he’s started on whisky, and it’s getting worse.

He’s tried to stop. He’s been to rehabilitation centers, outpatient programs, and Alcoholics Anonymous. Every time, he tapers off attendance because somebody annoys him or he doesn’t like something about the program. Then he starts drinking again, one glass at a time, quite sure he’ll stay in control this time. He can’t imagine not wanting to drink. Sometimes he manages to control it for a few months, but eventually stress steps up, his drinking increases, and in a year or so, he’s back in rehab. He knows he’s in a desperate situation and his body, at age fifty, can no longer tolerate alcohol.

Everyone he knows can see what he needs to do—stop drinking, stay in a treatment program, and not fool himself into believing he can drink moderately. W. knows this too, in his moments of clarity. Yet he seems unable to use the knowledge he has. Some other factors are operating here.

A.’s neck hurts all the time. She’s had lots of massages, chiropractic adjustments, and so on, which help for a while, but the pain always comes back. You couldn’t say she was addicted to her pain—she hates it and would love to get rid of it—but some part of her requires it, or it would not persist so long after the initial cause.

Another client, P., goes through life trying all kinds of New Age therapies to cure his depression. Nothing seems to work for long. He’s tried medication, but that didn’t help either. The therapies have increased his awareness of his childhood issues and given him great insight into his personality. But his depression—though it ebbs and flows in ways that seem unrelated to his treatments—doesn’t really get better.

I’m often a last resort. Like these three clients, many people, most of them quite sophisticated, come to me with what seem like intractable problems, after they’ve tried “everything else.”

I got to asking myself—why does one very useful and valid treatment work for some and not for others? Why doesn’t anything, apparently, work for some people? And why does the body hang onto symptoms and pain as though life depended on it? Do we have some strange need to be unhappy? None of these behaviors seem to serve any useful function.

Until recently, many therapists, especially those strongly influenced by New Age doctrines of personal responsibility, believed that there was some kind of “victim mind,” which makes a person gain enough perverse satisfaction out of not getting better to warrant staying with their sickness. Actually, this idea goes back to Freud. He proposed that we are constantly stimulated and driven by a balance of two energies, represented by the mythical figures Eros and Thanatos. Eros is the sexual drive and creative force, while Thanatos is the death force of destruction. A person could be unbalanced, remaining in the self-perpetuating destructive behavior. The patient would resist treatment because of certain “secondary gains” of their illness, which could be physical, economic, social, and so on. The danger of this idea is twofold: It provides a convenient out for a therapist whose client isn’t getting better, and it ends up blaming the victim while not identifying possible other culprits. It seemed to me, also, that at a biological survival level it makes no sense for an organism to be so self-destructive.

The same internal process—the body wisdom, which keeps our physical selves alive and more or less healthy—is responsible for addictions, intractable pains, and self-sabotaging behavior. The body wisdom is attempting to fill a need, but with limited or incorrect information. Since that part of us functions in a simple, binary fashion, and we are living in a very complex, civilized world, our needs become convoluted and distorted by what surrounds us.

WE ARE THE PROBLEM

Most of the people I see are smart and analytical enough to be quite aware of their own problems. But when they take steps to change things, these lower-brain, biological factors that don’t think or analyze take over and control the outcome. All imbalances and ultimately all diseases originate in a real need that the organism is driven to fill, but for some reason cannot satisfy with what is truly needed. The environment may not supply it, or the individual may have the wrong information about what is available to him, whether his choices come from information encoded in his DNA, or from limited past experiences, or just incorrect perceptions.

For example, if W. has a genetic, metabolic deficiency in one or more of the liver enzymes that break down alcohol, he is more likely to have a body that perceives alcoholism as a solution to his emotional needs than someone who has different genetics. Another person might choose (unconsciously, of course) psychotherapy, love relationships, religion, or another kind of “addiction” to satisfy emptiness.

If the key fits the lock—in other words, if the object chosen to fill emotional hunger is truly satisfying and not a substitute for the real thing—the need is satisfied and balance is restored. If it’s not the real thing, the needs are still there, untouched, despite the activity on the surface.

W.’s need is still there, and until he can satisfy it, he will remain an alcoholic or, at best, a “dry drunk”—someone who is still an addict with unfilled needs, who has to “white knuckle” through life and will probably fall into another addiction.

Unfortunately, the behavior of drinking and its compulsive nature creates its own problems. W.’s physical ailments and his inability to stand frustration or reason coherently come from the biochemical changes of alcoholism and also get in the way of his healing. He would have to access those unfilled needs—biochemical, spiritual, and emotional—perhaps by staying in Alcoholics Anonymous until he gains spiritual fulfillment and his emotional needs are met through the support of others—before his desire for alcohol will go away.

That’s why willpower and conscious intention don’t work in the long run; stopping the behavior without filling the real need creates resistance and even panic on a survival level. Anyone who has tried to go on a strict diet knows this.

The other reason our conscious efforts don’t work when a problem is deep seated is that we are the problem. If we have created it, the attempts we make to get better will come out of the same tendencies and distortions, the same limited information, as the problem. Most of us know this on some level, and so we go to others for help, hoping an outside viewpoint will give us the extra energy we need to heal. But even our choice of healing modalities will reflect our prejudices. Somebody who is very physical and sensation oriented will try to help herself with exercise and sports, whereas a cerebral, analytic person will go to therapy and a spiritual person will turn to religion—all for the same problem. Often what’s wrong with us—that blind spot—is obvious to those around us, since it tends to be out of our field of vision and directly in theirs. We know just what someone else needs to heal, but we can’t fix ourselves.

KYO AND JITSU: A STARTING POINT

So how do we help ourselves, given all these limitations? Eastern medicine provides a paradigm that helped me gain an understanding of this problem and showed me how to step outside the maelstrom of neurosis and imbalance to know at least where to start.

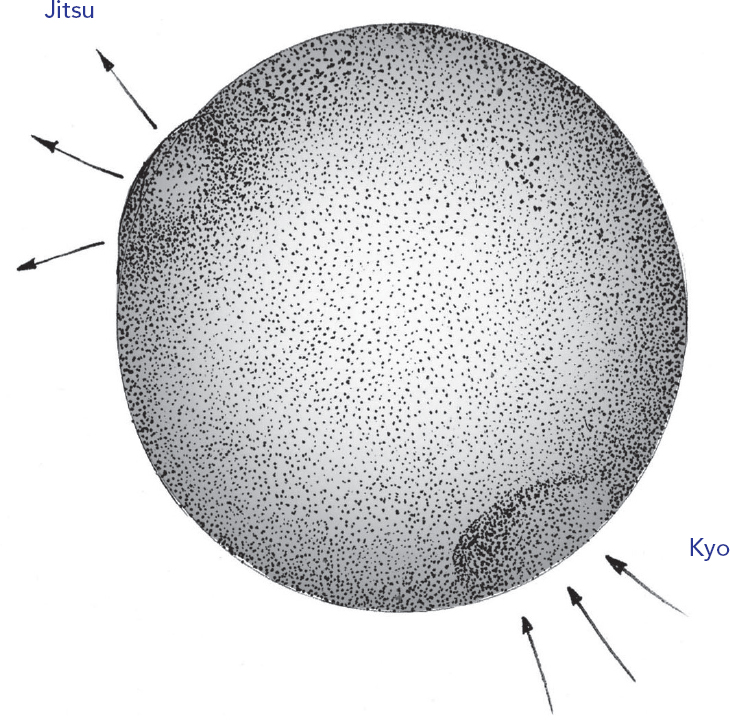

These ideas come from the work of Shizuto Masunaga and Wataru Ohashi, authors of Zen Shiatsu, How to Harmonize Yin and Yang for Better Health,*2 who explain this from the Eastern point of view much better than I can. They wanted to integrate these ancient ideas with Western psychology. This is my interpretation of it. As Masunaga saw it, the need—emptiness, lack, deficiency, weakness, negative space—is called kyo (in Japanese); the behavior—symptoms, manifestation, pain, that which is active and conscious—is jitsu (see fig. 1.1 below). The kyo (need) creates an imbalance in energy, which the organism will fill—either correctly (balance is restored again) or not (jitsu).

The jitsu, since it doesn’t really fill the kyo, just sits there, unintegrated, and causes its own problems. The kyo still pulls us, drives us to fill it. If we try again, in the same misguided way we did before, we create another jitsu, which could be a habit or addiction. In the example we used earlier, W. needs emotional and spiritual nurturance (kyo) and drinks as a substitute (jitsu). Drinking provides him with excitement, relaxation, and a feeling of warmth but doesn’t satisfy the real need (kyo). The glow wears off, he feels his needs again, plus whatever chemical and emotional problems the drinking created. Then, because he doesn’t know how to fill these needs, he drinks even more (jitsu). Alcoholism is the most obvious illustration of kyo and jitsu I can think of.

Fig. 1.1. Kyo and jitsu

Let’s go back to A.’s neck problem and see how the kyo/jitsu dynamic operates there. Her jitsu, of course, is the neck spasm. It’s obvious, it hurts, and it’s what she’s most aware of. When she takes steps to remedy the neck spasm—goes for a massage, takes medication, buys a special pillow for her head, and so on—her neck stops hurting for a while. Then the pain comes back, just as severely.

So what is the kyo here? It depends on what point of view you look at the issue from. At a structural level, A.’s lower back muscles are weak and do not support her body correctly. She sits at a desk in front of a computer all day, with her head craned forward, the weight of her head falls onto her neck muscles rather than her whole back. Because her back is weak, as the day goes on, she slumps more and more in her chair and her head pokes farther forward, creating more pain for her. The unmet need in this case is to support her head correctly, with the muscles designed for the job.

From a psychological perspective, the neck pain could signal dissatisfaction with her job, which would be the kyo. She’s not aware that she doesn’t like her job—she does it mechanically, doesn’t think about it—but her resistance and lack of energy about it show up in her slumped, depressed posture, which then creates the tension in her neck. Her unfulfilled need would be for satisfaction in her work life.

If you look into her situation from other points of view, you might find even more kyos. We might find that changing one of them helps a little, but not enough to completely cure her pain. Actually, this is the most common pattern I see in a client, because usually by the time they come to me, kyos and jitsus have interlaced and layered in a complicated way, reacting to each other until the origin may be quite obscure.

First Layer of Kyo and Jitsu

Kyo and jitsu function in layers. The first layer, the most superficial, and the one that changes the most easily, is the most recent. For example, if I do something that doesn’t conform to one of my habitual patterns—suppose I garden or use a computer, things I never do normally—and I pull a muscle slightly, I might then go to a therapist, who will treat me once and I won’t have the pain any more. That’s the true first level kyo/jitsu. Children, since they haven’t lived long enough to form habit patterns, recover quickly and dramatically if their first level of kyo/jitsu is healed.

As soon as we develop unresolved, compensated, and stuck tendencies, we have the possibility of a temporary slight injury hooking in to an old pattern. In this case, even if the stimulus is new—my gardening injury, say—my body will file it away neurologically as “pulled neck muscle, just like all those whiplash injuries I had when I was a child, so let’s spasm up in the same old way.” This injury will take longer to heal and will need more attention, since I will need to treat the unresolved whiplash too.

A.’s neck pain may be a recent “crick” in her trapezius muscle, which she pulled today as she was talking on the phone while she was on her computer. That’s the first layer—the pain she acquired today, which will go away quickly after some bodywork. It might resolve on its own too, although it may create compensations. In A.’s case, though, the problem goes deeper and, even though she feels relief when she leaves me, her pain all gone, unfortunately, when she goes back to her office, sits at her desk at that same slight angle, and juggles the telephone and computer work, she feels a slight twinge again. We did not—could not in one treatment—approach the second layer, and that’s what she’s feeling now.

If her first layer is the relationship between her neck and lower back, it will correct easily. She’ll feel much better right away and probably think her problem has gone. But it hasn’t; perhaps it will reappear, less acute but still bothersome.

Second Layer of Kyo and Jitsu

The second layer is much more complex. This is the place where patterns are created and maintained, where compensation happens and there starts to be a struggle. It can be discouraging. The second layer is the source of the experience A. may have (it’s a common one) when she feels she is “magically” healed after a few treatments or when she realizes that her lower back muscles, after she strengthens them, stop the neck pain. The pain recurs, perhaps not as badly or in a different location, but something is still wrong. One kyo is satisfied, allowing the other ones to surface. Depending on the complexity and duration of her problem, she will find a whole assortment of interweaving kyos and jitsus that may reveal that this minor neck pain is part of a system that reaches deep into every aspect of her being. If the problem clears up in a few treatments or if an exercise fixes it for good, that means the neck problem is superficial, that it has roots in the first layer.

Third Layer of Kyo and Jitsu

Most issues that bother you, that seem chronic at all, have roots in the second layer. If you keep going with the uncovering process, eventually you will hit the core, the third layer, which in many ways is a very difficult place to land. Change in the third layer can’t be forced, and—since your body wisdom believes your survival depends on maintaining the imbalances within it—you will meet enormous resistance to these deep changes. If you don’t find resistance, you haven’t gotten to it yet.

The contents of that core relate to identity and self-definition, so if they shift, something radical is going to change that will threaten the person’s fundamental sense of who he is, even if that change feels wonderful—what could be bad about being free of neck pain, not being addicted to alcohol, or not being depressed? Because of the threat to survival involved, there’s still a mental reflex that we might recognize as resistance or feel as anxiety.

Kyo/Jitsu Layers in the Body and Aspects

The kyo/jitsu layers exist spatially as well as in time. People tend to be soft on the outside (kyo) and hard inside, through the deeper muscles (jitsu), or the reverse may be true. Dancers, for example, are often very flexible and have soft mobile tissue on the surface of their bodies. They might seem relaxed and fluid in their movements. But their structural issues are usually in the deeper muscles, which can grip with great force and cause a lot of problems. Other athletes, such as football players, have big, hard, tight outer bodies and inflexible joints, but weak, soft deeper muscles. Both these situations are unbalanced, and, ideally in any physical activity, the aim should be the distribution of energy through the body equally.

The first layer, in this aspect, would be the skin and the surface tissue—the part you can feel easily. It would also involve how a person looks and what you notice about her visually—the “skin deep” impression. The second layer would be most of the body tissue, the muscles you can feel without too much difficulty, and maybe some of the organs—the stomach and the esophagus are probably second layer.

The core contains the deep muscles: the psoas muscle, which, simply put, runs diagonally from the anterior lumbar spine to the groin through the body, joining the upper and lower torso (see fig. 7.1), parts of the diaphragm, most of the organs, and the bones. It’s hard to feel the core tissues, but they create and form our structure and our deeper emotional life.

Finally, there are the areas in which kyo/jitsu express themselves—the aspects. The dynamic can be structural, as in A.’s neck problem. It can be energetic/psychological, as in W.’s alcoholism. It can be expressed in a disease state, as depression (see below). It can also exist in relationships between people. You see it in disturbed families, where the “identified patient”—such as the family member whose crazy behavior troubles the other members—gets better and stops acting out. In this case the jitsu is quelled, but the kyo is not filled. So the jitsu will travel to another family member, who will act out the disturbance in his own way, creating another jitsu, until the deeper kyo of the family is healed. I’ve seen this in my own work where parents bring in their “problem kids.”

L., for example, brought in his sixteen-year-old son, who had attention deficit disorder and had started getting headaches. It’s usually a sign that the parent is involved in the kyo/jitsu dynamic when they come into the treatment room with an older child or adolescent. When L. and his son arrived, he told me all about his son’s issues in a way that made it apparent that the son’s problems were a strong focus for the father. In such a situation, where I’m not doing family therapy, my recourse could be to (a) ask the parent if I can work with the son alone, or (b) speak to the father about what I’m feeling, either directly or by expressing that what the son might need in order to get better is a certain amount of emotional space.

P. suffers from depression. He has a couple of dynamic jitsus. I learned this by chance when his wife came in for an unrelated injury. P. admired—even envied—his wife and told me often what a wonderful, dynamic woman she was, and how bad he felt that his depression was dragging her down. I did suspect that he might be angry with her, but conversation along those lines never went anywhere, and he’d been to so many therapists that he must have been aware of his anger by now, if he ever would be.

When I met his wife, she did seem like a very energetic sort of person whose positive energy more than made up for P.’s inertia. As she talked about herself and how she had come to the injury she had, what emerged for me was an impression of somebody who had experienced a lot of loss and trauma—far more than depressed P. had. So much, in fact, that she’d completely repressed the possibility of sadness—“I’m never depressed!”—and P. was expressing it for her.

His depression, in this sense, was the jitsu of their dynamic—it was the obvious, wrong thing that took up a lot of their energy—and the kyo was her denied depression. Her need, I would imagine, was for some kind of expression and nurturance of her sadness, some attention. But since P. was getting all the attention and all the therapy, her kyo never rose to the surface, and the closed system of their dynamic remained intact and unconscious.

Family therapists are very aware of this kyo/jitsu interaction between people, although they express it in different ways, such as “projective identification,” “enabling,” and so on. It can create a lot more sickness than intrapersonal kyo/jitsu, since the basis of an entire relationship may depend on it. For example, it’s possible that P.’s recovering might allow his wife’s depression to emerge. Then, if the basis of their relationship is not so healthy, their marriage might be in danger. Since P. doesn’t want to risk his marriage, he can’t allow therapy to succeed.

We can see from these examples some of the ways in which the kyo/jitsu dynamic can operate, and of course they all interweave in any given real-life situation.

Kyo/jitsu can exist spatially, within the body, as a weak (kyo) system creates an overfunctioning (jitsu) area somewhere else.

It exists in time, as in the most recent and superficial kyo/jitsu imbalance, which is easier to correct, versus the much older and more complicated kyo/jitsu patterns that only emerge after the recent ones are balanced.

It exists interpersonally, between people and in situations.

It manifests psychologically in conscious (jitsu) and unconscious (kyo) patterns.

P.’s depression, for example, as well as the jitsu for his wife’s depression, could also be a jitsu for his own kyo feelings of anger and his unmet need to hit somebody.

FUNCTIONAL AND STRUCTURAL KYO/JITSU

Kyo/jitsu, on a more physical level, could be structural (weak muscle/tight muscle) or functional (unexpressed movement/overemphasized movement).

How do you move all day? A., the lady with neck pain from the beginning of this chapter, is sitting in front of her computer, tilted slightly at an angle. That’s her movement jitsu—it’s noticeably static and upper-body focused. Her kyo, those movements she never or seldom does, might be strong, fast lower body movement like dancing or sprinting. Maybe it would help her neck problem if she started becoming more active in this kind of way. A very active, athletic person, on the other hand, might be helped by sitting still.

Functional kyo/jitsu can be more specific than that. Various dance-based therapies analyze all human movement in terms of choreography. There are lateral (side-to-side), rotational (around), vertical (up-and-down), flowing, stuck, fast, and slow movements. As small children, we have access to the whole gamut of human movement and can learn movement skills very easily, just as our unconditioned mouths can form words in many languages. The culture and socioeconomic group we grow up in creates our first shaping of movement expression. If we grow up in an Italian or Spanish environment, for example, we may learn to use our arms and hands quickly and expressively when we talk, not held in close to our sides. Certain muscles then get more developed, and others don’t get used so much, forming characteristic body shapes. We might also learn, or not cultivate, particular body skills as children. Perhaps we learn a sport, or maybe the movement skill we learn is just sitting in front of the TV for hours on end—these activities all create movement patterns that develop our bodies in particular directions.

Repetitive stress syndrome, tendonitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and so on are created by a limited jitsu movement pattern. The therapist will give exercises that explore and strengthen different movement pathways—the kyo functions. At least one of these weak movements is likely to be the underlying kyo.

Doing something different, almost any change in movement patterns that isn’t harmful, is likely to hit a functional kyo and correct a jitsu somewhere. But here’s the catch: If you just move randomly, letting the body express itself as it chooses, you’ll probably only repeat the same movements you are already strong in. You have to learn something different from the outside, a new skill.

The computer programmer with carpal tunnel syndrome takes up rock climbing, and the new upper body patterns strengthen muscles that she can then use to release the other, overworked muscles that are giving her pain. The football player learns yoga and starts to use extended, stretched muscle patterns, correcting the imbalances that create the contracted muscle paths causing his tendinitis.

What’s the opposite of your habitual movements? What might change if you incorporate some opposite, unfamiliar patterns?

USING THE KYO/JITSU PARADIGM

We can see the kyo/jitsu dynamic in relationships, in structure, in organic functions (an overfunctioning stomach might be caused by an underfunctioning liver, for example), in psychology, in function and movement, and you can probably think of many other areas where it manifests. Now, let’s look at how to use this paradigm. How can you find your own kyo? There is enormous power and the potential of healing if you can become aware of what in yourself is unconscious, weak, unfelt, hidden, and not used. The awareness itself invigorates the kyo and starts to wake it up so it can be available to you as energy.

Invigorate the Kyo

You have probably experienced some of this already in your life. Think of problems you’ve had that you “got over,” whether physical, mental, or emotional. You probably didn’t get over them by wrestling the jitsu into the ground—such as fighting the problem directly with willpower. You almost certainly transcended rather than won, bringing energy to other physical systems, learning a new way, having a life-changing experience, or doing something else that pulled awareness and vitality into what had, until then, been a kyo.

You can see this happen by chance when someone discovers a spiritual path, falls in love, or faces a catastrophe, and the flood of new input breaks the kyo/jitsu cycle. As we age and become embedded in habit and fear, we often stop the flow of new information, holding onto our jitsu and shutting off kyo from consciousness. So younger, or at least more youthful, people tend to fill kyo more dramatically and have fewer stuck patterns.

Let’s go back to A. with her neck pain. First of all, I’ll step back mentally from the minutiae of her problem in order to see the more general kyo/jitsu of her life. My first move is to go from the specific to the general, to see the biggest picture I can. I divide areas of emphasis into sections: relationships, environment, psychological, spiritual, exercise, diet, breathing, work, recreation, sleep, and so on. I look at her areas of emphasis. Perhaps A.’s area of emphasis is psychological; she experiences her neck pain as an emotional issue. Maybe she goes to her psychotherapist and talks about what it might mean, how her relationship stress might be causing it. Or maybe her work situation—she works sixty hours a week—is responsible.

What she never pays attention to is exercise. It never occurs to her that some type of movement might help her neck. So my first suggestion might involve her becoming physically active and perhaps doing some exercises to strengthen her back. My guess is that lack of movement is her neck pain kyo. Maybe she never pays attention to her diet, either. I pick movement first because it makes logical sense; her back muscles are weak and the sedentary nature of her work is making her compensate with her neck muscles. We have to start somewhere. I also have to find exercises for her that don’t create too much resistance, aren’t too opposite from her habitual way of being. Jitsu has to be placated! Also, I won’t make them too complicated and “dancerly”—I used to make that mistake a lot. I’ll explain them thoroughly—appeal to her mind—and emphasize the mind/body nature of movement.

Intensify the Jitsu

The other way we could work with kyo/jitsu is the exact opposite—intensify the jitsu to the point where her own nervous system recognizes there is an imbalance and corrects itself—a sort of vaccination process. In this case, perhaps if A. were completely and entirely still in her body and mind for a fixed period of time, as in some meditation practices, she might experience more deeply the nature of stillness and crave the movement that is its natural balance. There’s a risk in this approach—not so much for A., but for W., who may have to “hit bottom” with his drinking before he realizes he can’t fool himself any longer and may then seek treatment. Of course, the risk is that he will hit bottom and not come back up, that he may become seriously ill or die. So this approach is a little more risky than going directly to the kyo, because it presupposes some sense of natural balance that may not be there.

Working tight painful areas—jitsu—directly is our natural instinct, and usually a good one. We want to rub the areas that hurt and actually intensify the sensation there. One reason this works is that, when the energy is increased in the right place by rubbing or pressing on the area, the tension will naturally let go after a certain point. Lots of bodywork techniques work on this principle. If a muscle or joint wants to move in one direction too much, intensify the movement by compressing the joint into the favored direction. The nervous system may well readjust. Psychological jitsu can be increased by catharsis, exaggeration of the troubling emotion until the emotions balance themselves.

When a condition has just happened, right after injury or crisis of some kind, intensifying the jitsu will usually resolve the problem. However, in the course of my work, I rarely see people right after they have been injured. Compensation only takes about fifteen minutes to begin, at which time the patterns in the body shift, becoming complex, as the organism adapts to the insult. The only chances I’ve had have been when my kids have injured themselves when I’ve been right there and once when a client had twisted her ankle outside my building, just as she came in for her appointment. Then I’ve had the opportunity to experiment with this concept and worked directly into the injured area, with immediate pain relief. You can’t do this, of course, if a bone is broken or the skin is open. Usually in these cases the pain is not right at the injured site anyway, or the person is in shock and numb.

You can try working immediately with a minor injury like a stubbed toe. Press into the sore part until the sensation of pressure equals the pain of the toe. The pain may go away, or at least greatly reduce, and you may limit later swelling or inflammation.

You can also practice by allowing jitsu to fully express itself through movement. You can explore this with chronic pain, any kind of bound, tight, or pent-up sensation. See if you can be specific about the type of energy locked in the tissue—is it gripping, pulsing and throbbing, angular, or sharp? Experience it as simply as you can, as held energy, rather than pain. Without fear and projection into the future, pain becomes sensation, and the body can unwind. Resistance and tightening around pain is natural—but it will only prolong it and make it worse.

Psychologically, this principle is being used in the technique of thought flooding. I always thought positive affirmations didn’t work, and I was aware that I worried more, not less, after telling myself good things, surrounding myself with white light, and so on. Apparently, lots of people have this experience. A psychologist, Thomas Stampfl, has experimented with the technique of having a worrier think the absolute worst, most frightening thoughts they can (intensifying jitsu), without resisting them, for a limited period of time—say ten minutes a day. The rest of the time, the chronic worrier finds he automatically worries less and can control his thought patterns, knowing he has a “worry time” later to look forward to. It interested me how this practice gave me a sense of relief.

Some addictions can be handled this way too, limiting the time period they can be indulged in, and strictly refraining the rest of the time. However, the more powerful ones have a chemical component that does not allow purposeful indulgence, or are too damaging to engage in at all.

Finding and Filling Kyo

Intensifying jitsu is usually the first way I go with a client. It satisfies them—the issue they come with is given attention. It often works. If I have no success with this approach, we then need to begin the deeper and more profound task of finding and filling the kyo.

There are many layers, of course, and many kyos. However, there is always one deep and fundamental kyo underlying the structures, hiding in the third layer, the core. Finding this in oneself is usually a lifetime task. If you bring energy fully into your own blind spot, you will completely heal (make yourself whole).

Getting the Right Balance

D. came back to me for treatments after a hiatus of several years. She had had a car accident when we had last worked, and the resulting cranial injury from whiplash had caused her excruciating headaches. That was all fine now; the current problem was a strange tightness in her hips and hamstrings that wouldn’t go away no matter how much she stretched. She had tried Rolfing, chiropractic adjustments, and two-hour-long deep tissue massages, but the pain always came back by the next day.

I looked at her hips; all that excellent bodywork had loosened up the muscles around that area so much that the tension melted away as soon as I worked into it. It was easy—too easy. Obviously, that wasn’t the solution, since all her tension always came right back the next day. I wasn’t sure why. The Rolfer and the deep tissue masseur had worked in the hip rotators and her gluteus—I thought perhaps the problem was coming from her psoas and quadratus lumborum. Sure enough, there was a bigger change when I worked there, as I would have expected. Working opposing, antagonistic muscles is often the solution to an intractable problem.

D. came back the next week, disappointed. “It all came back the next day, just like before. How many sessions do you think this will take?”

“Four,” I said, out of the blue. For some reason, I always know in four sessions if this is a problem I can work with, and if so, how. That doesn’t mean the problem is gone in four sessions. She understood that.

This time, I worked with the rest of her body, seeing if I could find some other factors that perhaps had been overlooked by the other therapists. She was extremely tight everywhere else in her body; the painful hips seemed to be much looser than any other area. I didn’t find anything that seemed particularly related to the hip problem, and she left. I mulled over the conundrum all week—nothing came up for me that helped me identify what might be causing her problem.

The next week she came back, much happier. “The hips are much looser,” she said. We were both surprised. “Now I can feel how locked up the rest of me is!”

Now her hips were looser and the original problems with whiplash were starting to show up. I continued what seemed to be helping, that is, giving her more of a whole-body treatment, and as I worked on her, I got it.

Her body was so tight from the car accident, and all the compensations since then in her spine, that her hips were the only mobile part. The rest of her body, though very jitsu to the touch, was functionally kyo—unaware, unmoving, not much energy in it. The hips, though loose and mobile, had become the functional jitsu—they moved too much, taking on the work the rest of her couldn’t do. And in fact the tightening up was due to overstretching—even though the hips were tight, they were loose relative to her body.

Working the rest of the body (the kyo), and allowing it to be more mobile, meant those overstressed hips had to do less work, so they relaxed. Working into the hips and opening up the surface tension there might actually intensify the problem, since compensation would increase.

So paradoxically, the problem places in your body could be the most flexible areas that have to work too hard, and you may need to open up the rest of your body. Often, the tight places actually need to be strengthened and the rest of the body made more flexible.