Pringle Rose, her brother Gideon, their family and friends, and other characters in this book are products of my imagination, but the details of their lives and the anthracite coal miners’ strike of 1871 and the Great Chicago Fire are as true as true can be.

In the nineteenth century, girls from middle- and upper-class families were encouraged to keep diaries. Many girls like Pringle were given a diary as a special birthday present from their mothers, who believed diary keeping would encourage self-discipline, nurture good character, and help their daughters grow into respectable young women.

For some girls, diary keeping was a social activity. At boarding schools, girls wrote expressively in their diaries and in each other’s. (Sharing a diary was a sign of a special friendship.) At home, mothers and daughters often read aloud from their diaries. Some mothers wrote helpful notes in the margins and offered suggestions. For other girls, diary-keeping was a private activity that allowed them to take risks and explore their feelings.

In the United States, girls attended private boarding schools as early as 1742, when a sixteen-year-old countess named Benigna von Zinzendorf founded Moravian Seminary for Girls in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

By 1871, the number of private schools for girls was on the rise. Most boarding schools did not think a girl’s academic education needed to equal a boy’s. These schools emphasized traditional values, preparing girls for their future roles as wives and mothers and in service to others.

But some more progressive schools offered a rich and varied curriculum, including subjects such as Latin, French, German, spelling, reading, arithmetic, trigonometry, history, and geography, as well as chemistry, physiology, botany, geology, astronomy, and daily exercise.

As the Industrial Revolution transformed America, men, women, and children labored long hours — usually ten to sixteen hours per day, six days a week, for low wages — in mills, factories, mines, and other industries. The workers had no vacation or sick days. They had no paid holidays. They suffered dangerous and unsafe working conditions.

Many workers immigrated to the United States from other countries. Some of these workers came from countries where workers had already begun to organize and were fighting for an eight-hour workday and other concessions from their employers. In England, women and children had won a ten-hour workday.

By 1871, American workers were forming unions in order to fight for higher wages and better working conditions. Workers had learned that when they united, or unionized, and acted as a group, they stood a better chance of making their employers agree to their demands.

In the beginning, employers tried to prevent unions from forming, and even attempted to destroy unions. They refused to “recognize,” or to deal with them. If workers went out on strike, the employers hired other workers, known as strikebreakers or scabs.

Other people opposed unions, too. In the eyes of the public, the employers were important men who invested their money, created jobs, and made the growth of the industry — and therefore the country — possible. The public worried that higher wages would mean higher prices. Furthermore, most employers were native-born Americans, whereas workers tended to be new or recent immigrants. For these reasons, many native-born Americans sided with employers, not the strikers.

In 1868, anthracite coal miners formed the Workmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA). In early January 1871, anthracite coal miners went out on strike for the third time in three years over the issue of wage cuts.

After the striking workers rioted in Scranton on April 7, 1871, the Pennsylvania governor sent in the militia. Despite martial law, the riots continued, especially as some men quit the strike and returned to work. A shooting incident killed two striking workers.

On May 22, the striking men agreed to a compromise: They would return to work and their grievances would be decided by arbitration.

During arbitration, an arbiter acts as a judge, listening to both sides and then deciding the verdict. After influential men depicted the striking workers as criminals, the arbiter favored the employers. As a result, the striking men lost their fight. The mine workers were given wage cuts. Employers were forbidden to hire only union men, which undermined the union’s power. This judgment made mine workers more determined than ever.

Over the next five years, several more bitter strikes took place as the miners continued their fight for an eight-hour workday, higher wages, better working conditions, and recognition of their union.

As labor unions continued to grow throughout the United States, employers continued to oppose unions. (By 1900, Chicago became one of the most heavily unionized cities in America — and a center of anti-unionism.)

Employers fired workers who belonged to unions or who were sympathetic to unions. They recruited strikebreakers, or men who crossed the picket line to replace the striking workers. They created or exacerbated tension between ethnic groups in order to divide workers. They vilified unions and depicted unionized workers as criminals, calling them anarchists and Communists.

Employers turned to lawmakers for help in enacting laws against unions. They also hired thugs to attack union leaders and union sympathizers. They formed private, armed militias and created their own police force, such as the Coal and Iron Police in Scranton and the Pinkertons in Chicago.

After many bitter battles, unions won recognition and won many gains for workers, including higher wages, shorter workdays, and safer working conditions.

In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) established a national minimum wage and time-and-a-half overtime wages in certain jobs. The FLSA also established child labor laws that restricted the employment of children.

In the early part of the nineteenth century, women did not have the right to make a contract, which restricted a woman’s right to buy or own property. She could not keep the money she earned. She could not vote, run for office, or serve on a jury.

If a woman inherited property or money, everything she owned became her husband’s — and remained her husband’s, even if they divorced. Her husband controlled all the property. Children were also considered the father’s property.

In 1848, New York passed the Married Women’s Property Law. A few weeks later Pennsylvania followed suit, and over the coming years, other states would, too. This law gave women the right to retain the property they brought into marriage. The law also protected women from creditors seizing their property to pay their husband’s debts.

Some husbands found a way to get around the law. In some cases, wealthy or propertied women were committed to asylums against their will because their husbands wanted to keep the wife’s property. Although some women may have suffered mental illness, others found themselves committed when their husband wanted a divorce, or when the women didn’t behave the way society expected a wife, mother, or daughter to act. For example, one woman was committed when she got a job without her husband’s permission. Another woman was committed because she held strong opinions that differed from her family’s views.

Although it’s never stated in the story, Gideon Rose is a child with Down syndrome. His character was inspired by a man named Sal Angello, whom I knew for many years and to whom this book is dedicated.

Although the characteristics of Down syndrome were identified in 1866, it took nearly one hundred years for a French physician to discover that the syndrome was the result of a chromosomal abnormality. His research led him to the fact that people with Down syndrome have 47 chromosomes, whereas people without the syndrome have 46. A few years later, it was discovered that chromosome number 21 contained an extra partial or complete chromosome in people with Down syndrome.

No one knows what causes the presence of an extra chromosome 21. The extra chromosome can come from the mother or the father, but most likely the mother. It is not hereditary. At this time, there is no way to predict whether a parent carries the extra chromosome.

Babies with Down syndrome are born into all kinds of families, regardless of race, religious background, or economic situation. Thanks to modern medicine, increased awareness, and family and community support, people with Down syndrome live full, rich lives as family members and contributors to their communities.

The nineteenth century is also marked by a concern for the rights of animals. Henry Bergh founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in New York City in 1866. The ASPCA is the oldest and first animal welfare organization in the United States. By 1888, thirty-seven out of thirty-eight states in the Union had enacted anticruelty laws.

Ironically, the United States enacted laws to protect animals from cruelty before it had laws to protect children. In 1874, when Henry Bergh learned that a nine-year-old orphan girl was routinely beaten and neglected at her foster home, he consulted his attorney. The attorney argued that laws to protect animals should not be greater than laws to protect children and won the right to remove the child from the foster home. Later, Bergh and his attorney created a charitable society devoted to child protection, the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. It was the first such organization in the world.

The nineteenth century is also marked by great changes in transportation, thanks to development of the railroad and the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Despite great advances in railway travel, it took a passenger between thirty and forty-some hours over approximately three days to travel from Scranton, Pennsylvania, to Chicago, Illinois, depending upon connections. The route that Pringle takes is based on a railway timetable from the period.

The train wreck that occurs in Pringle’s story is a product of my imagination, based loosely on an actual train disaster that occurred outside Angola, New York, on December 18, 1867, when a faulty axle caused two cars from the Lake Shore Express to derail and uncouple as the train approached a bridge. The rear car crashed down the icy embankment and burst into flames. The second-to-last car fell down the opposite embankment, splintering into pieces. Forty-nine passengers died. Most were burned to death. Just before the accident, thirty-nine-year-old Benjamin Franklin Betts felt a trembling motion and quickly moved to a forward car, an action that may have saved his life.

In October 1871, Chicago was a tinderbox. The downtown had tall wooden buildings, large wooden cornices, long wooden signs, and mansard-style top stories of wood. Chicago had miles of wooden streets and sidewalks.

Middle- and upper-class neighborhoods had wooden-frame houses and wooden roofs covered with felt, tar, and shingles. In the poorer neighborhoods, homes were built close together with small yards. Pine fences separated the dwellings and penned in livestock. With winter approaching, residents piled wood and wood shavings. They heaped hay in sheds and barns to feed livestock. In other areas, kerosene was stored.

Chicago had fires before. The previous year, the city firemen battled 669 fires. But this October was different. The city was dried out from a long drought. The firemen were exhausted from battling nearly daily blazes, and equipment was badly damaged.

On Sunday, October 8, 1871, Mathias Shaefer stood sentry duty on the courthouse tower. As Shaefer looked through his spyglass, he noticed blue curls of smoke rising from the still-smoking coal banks along the Chicago River. The smoke was leftover from the previous night’s fire that had razed sixteen blocks on the West Side.

Then Shaefer spotted flames near Canalport Avenue and Halsted Street. He reported the fire to William Brown, the night operator, and told him to strike alarm box 342. Brown pulled the alarm. A few seconds later, the nearly 11,000-pound courthouse bell tolled, warning the city residents. Firemen headed for Halsted Street.

From the balcony, Shaefer continued to watch the fire. Suddenly, he realized he had made a mistake. The fire wasn’t near alarm box 342. It was near 319. Quickly, he told Brown to strike box 319.

Brown refused. It might confuse the fire companies, he said. And besides, the firemen would pass 319 on their way to 342. (Unknown to Shaefer, a storekeeper had already reported the fire, but the alarm failed to register at the courthouse.)

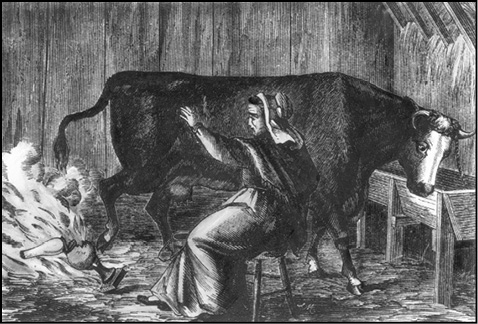

As Brown predicted, the Little Giant fire company had spotted the fire, and a steamer was headed to the scene, a cow barn at 137 De Koven Street. Within forty-five minutes, seven fire companies were fighting the blaze.

But the fire companies arrived too late and conditions were too great. In less than an hour, the fire consumed an entire block of shanties and was heading for the planing mills, furniture factories, and lumberyards near the river. At first, firefighters and onlookers believed the fire would burn itself out, once it reached the razed area or the river.

They were wrong. At 11:30, a flaming mass swirled over the river. It landed on a horse livery stable and struck the South Side Gas Works. Now the fire was headed in two directions, eating its way north and south.

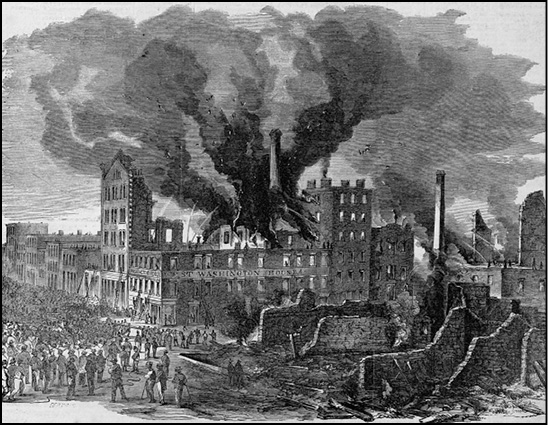

The fire burned for thirty hours, leaving a swath of burned-out buildings four miles long and one mile wide. It seemed like a miracle when it rained Monday night and into Tuesday.

All in all, it’s estimated that at least $200 million worth of property was destroyed. (That’s over $3 billion today.) The fire consumed seventy-three miles of wooden streets and 17,450 buildings. It left 100,000 homeless and an estimated 300 people dead and another 200 missing. (Only 120 bodies were recovered.) We’ll never know the exact number.

One of the great ironies of the Chicago Fire is the fact that another, even greater fire occurred at the same time in the small lumber town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, where lumbermen cut timber for buildings in Chicago. The fire tore through the streets so quickly that scores of people could not outrun it. The town’s population was about 2,000. Over 1,100 people were killed in the fire.

Godey’s Lady’s Book was a popular women’s monthly magazine published in Philadelphia during the mid-nineteenth century.

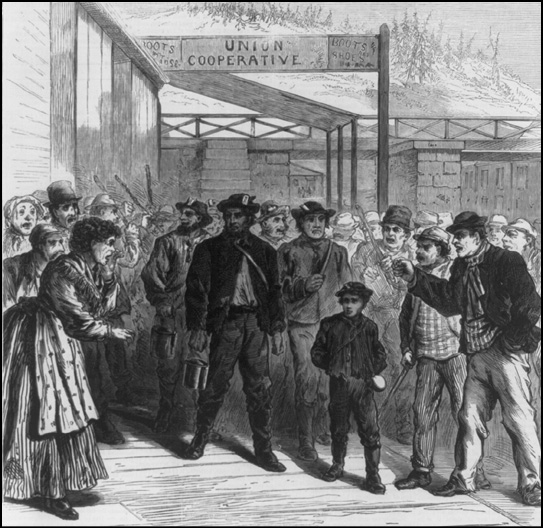

Protesting the dangerous and inhumane working conditions to which they were subjected, workers in the coal mines, or collieries, of northern Pennsylvania began to unionize and strike in the mid-1800s. Colliery owners, refusing to succumb to the demands of the workers, often brought in “scab” workers to take the place of the men on strike, thereby maintaining the terrible conditions. In this March 1871 illustration from Leslie’s Popular Monthly, a crowd of miners and their wives are taunting the scab workers. In early April, the strike turned so violent in Scranton, Pennsylvania, that the governor sent in the militia.

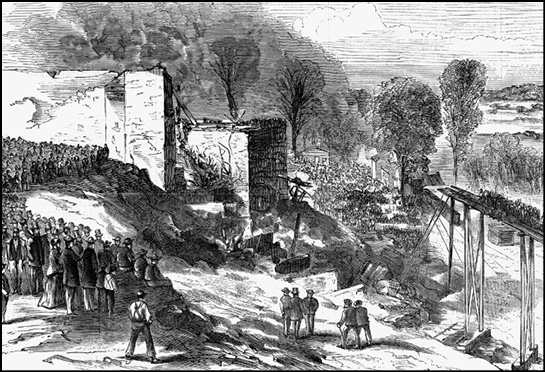

The Avondale Mine Disaster took place in Plymouth, Pennsylvania, on September 6, 1869. When the lining of the mine shaft caught on fire and collapsed, over 108 men and boys were trapped and suffocated, making this tragedy one of the worst mining disasters in Pennsylvania history.

The grim aftermath of the Avondale Mine Disaster.

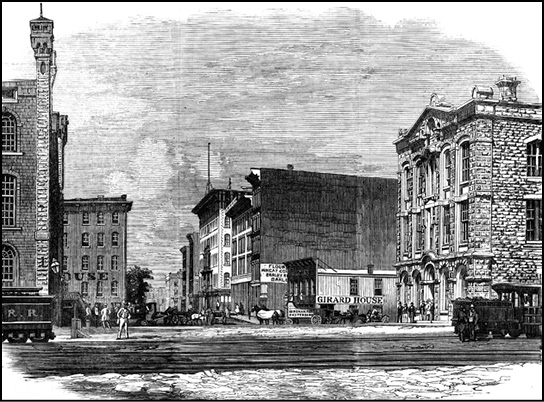

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Chicago was the primary transportation hub of the continental United States. The city had rapidly expanded, and by 1870, many of the sidewalks, streets, and buildings had been raised for the implementation of the nation’s first underground sewage system. However, most of the construction was built entirely of wood. The summer of 1871 in Chicago was extremely dry, leaving the ground parched and the city vulnerable to fire.

The Cook County Courthouse was a remarkably beautiful landmark in Chicago before the Great Fire.

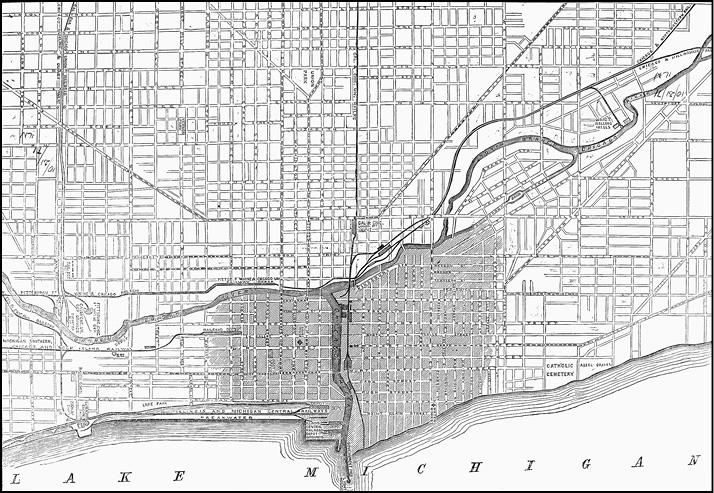

This map illustrates the spread of the Great Fire over three days, October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed an estimated 300 people and left another 100,000 homeless. At least $200 million worth of property was destroyed, the equivalent of over $3 billion today.

On Sunday evening, October 8, 1871, a raging fire erupted in a barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O’Leary at 137 De Koven Street. The next day, the Chicago Evening Journal reported a rumor as a fact: that the fire was caused “by a cow kicking over a lamp in a stable in which a woman was milking.” To this day, the actual origin of the fire is still unkown.

Not realizing how quickly the fire would spread, thousands of people turned out to watch the excitement.

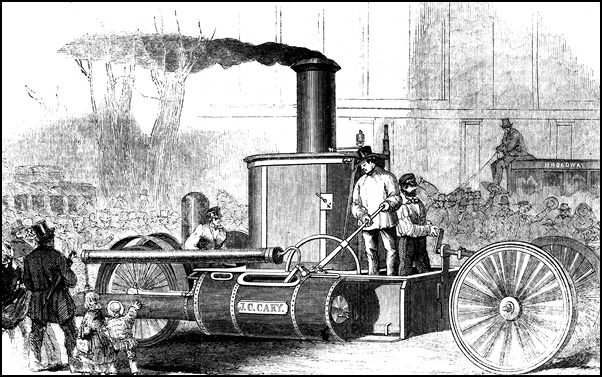

Steam-powered fire engines, like the one depicted here, were used during the Great Fire of Chicago.

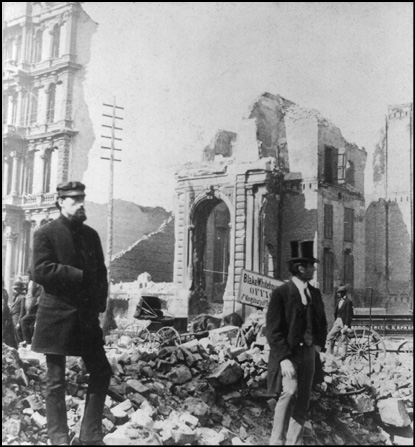

Two men stand in the ruins of what was once the northwest corner of Washington and LaSalle streets.

The fire destroyed nearly $200 million worth of property, leaving Chicago in ruins. An incomplete set of columns stands in place of what used to be the Fifth National Bank on the northeast corner of Clark and Washington streets.

Chicago’s first railroad depot, Union Depot, built in 1848, was destroyed by the Great Fire, leaving the station a wreck.

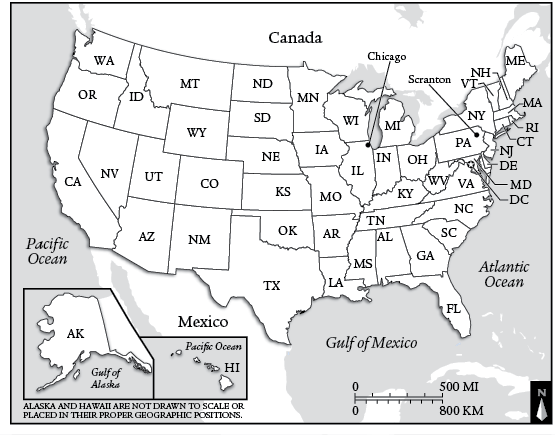

A modern map of the United States showing Scranton, Pennsylvania, and Chicago, Illinois.

The character of Gideon, Pringle Rose’s younger brother, was inspired by a family friend named Sal Angello, shown here.

(serenade)

Words and Music by Stephen C. Foster 1865

Beautiful dreamer, wake unto me

Starlight and dewdrops are waiting for thee

Sounds of the rude world

Heard in the day

Lull’d by the moonlight have all pass’d away

Beautiful dreamer, queen of my song

List while I will thee with soft melody

Gone are the cares of life’s busy throng

Beautiful dreamer, awake unto me!

Beautiful dreamer, awake unto me!

Steak and potato pies known as pasties are believed to have originated in Cornwall, England, where they were a staple food of workingmen, especially the mine workers. Records show that children who worked in the mines often carried the individual meat pies as their snack or lunch.

When English and Welsh mine workers immigrated to America, they brought their love for pasties.

Miners relished pasty, not just because of how delicious it is, hot or cold, but also because it’s moist. In the dust-filled coal mines, mine workers needed something moist to eat for their midday meal, to help get the coal dust out of their mouths and throats.

I have always admired the way my mother could roll out three or four pie crusts with ease. (The pie-crust rolling gene skipped me.) My mother’s pasty is delicious. Here is her recipe:

2 cups flour

1 teaspoon salt

2/3 cup shortening

6 tablespoons water

Measure flour and salt into large bowl. Cut shortening into flour. Sprinkle in water, one tablespoon at a time until flour is moistened and dough comes together.

Divide dough in half. Sprinkle flour over board. With floured rolling pin, roll dough two inches larger than pie plate. (This is where my mother says, “Don’t be afraid of the dough.”) Fold pastry into quarters and ease into pie plate.

After pie is filled, repeat with remaining half of dough.

1 1/2 pounds sirloin steak, trimmed and cut into 1/2-inch cubes

3 medium potatoes, peeled and sliced thin

1 medium onion, finely chopped

2 tablespoons flour

3 tablespoons butter

salt and pepper to taste

Layer one third of the steak, potatoes, onions, flour, and butter into bottom crust. Repeat two times. Cover with top crust. Trim excess dough. (Save dough scraps for cinnamon and sugar pastry.)

Moisten top crust with cream or milk. Bake at 400 degrees for 50–60 minutes.

In our house, scraps of pie dough were rolled into cinnamon and sugar pastries. To make your own, simply roll out excess pie crust. Sprinkle cinnamon and sugar over the dough. Dot with butter. Roll into crescent shape. Place in separate pie plate and bake alongside pasty for about 15 minutes.