Paraphrased from the Malay Annals

Paraphrased from the Malay Annals3 |

WEST MEETS EAST IN THE ARCHIPELAGO |

Here now is the story of Fongso d’Albuquerque of Pertugal [Portugal]. When he reached Melaka, there was great excitement and word was brought to Sultan Ahmad, “The Franks are come to attack us! They have seven carracks, eight galleasses, ten long galleys, fifteen sloops and five foysts.” Thereupon Sultan Ahmad assembled all his forces and ordered them to make ready their equipment. The Franks fired their cannon from their ships so that the cannon balls came like rain. The noise of the cannon was as the noise of thunder in the heavens and the flashes of fire of their guns were like flashes of lightning in the sky; and the noise of their matchlocks was like that of groundnuts popping in the frying-pan. So heavy was the gunfire that the men of Melaka could no longer maintain their position on the shore. The Franks then bore down upon the bridge with their galleys and foysts.

When day dawned, the Franks landed and attacked. And Sultan Ahmad mounted his elephant Juru Demang, The Franks fiercely engaged the men of Melaka in battle and so vehement was their onslaught that the Melaka line was broken, leaving the king on his elephant isolated. The king fought with the Franks pike to pike and was wounded in the palm of the hand. And he showed the palm of his hand, saying, “See this, Malays!” and when they saw that Sultan Ahmad was wounded, the chiefs and men returned to the attack and fought the Franks.

Tun Salehuddin called upon the Orang Kaya (nobles) to fight with the Franks pike to pike. And Tun Salehuddin was struck in the chest and killed, and twenty of the leading war chiefs were killed. And Melaka fell.

Paraphrased from the Malay Annals

Paraphrased from the Malay Annals

In the sixteenth century, the archipelago faced a challenge that was vastly different from its previous contacts with civilizations beyond the Malay world – Europe. India had come to the region to trade and had brought its culture as well as the tools Southeast Asians needed to be partners in a new economic world. The Indians, however, did not make any serious attempts to translate trade into political dominance.

The archipelago’s experience with China was even less dramatic. Between 1403 and 1430, the Chinese sent seven maritime expeditions into Southeast Asia. Each carried 27,000 men, but there was no attempt at conquest, except the occasional altercations at sea, nor any attempt to influence the culture of the area. Chinese culture was not easily exportable. Its philosophy/ religion was deeply embedded in race and tradition. The mixture of Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism and ancestor veneration was hard to graft onto another culture without a revolutionary change in the social system. The Chinese also felt that China was the center of the world, and other nations could not possibly achieve its sophisticated culture.

The Europeans, on the other hand, did not just want to trade with Southeast Asia – they wanted to control that trade and later, the people and their lands. Over a period of about three centuries, the people of the Malay world were to feel the impact of Western culture, science, and religion. Their social structures were shaken, their economies revolutionized and their trading power lost.

There were three main stages of European expansion of power and influence. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Europeans gained footholds on a few coastal areas and islands in the strategic sea lanes. These were basically fortified trading posts. In the eighteenth century, the Dutch in Sumatra and the Spaniards in the Philippines expanded their bases to control the hinterlands beyond the centers.

In this second stage, local rulers and traders continued to be significant players in the commerce of the area. While the Europeans were able to establish naval superiority, influence trading patterns and meddle in the politics of the archipelago, the process of cultural and racial exchange among Southeast Asians in the period 1500–1700 continued as it had for the previous 1,500 years. The Acehnese in Perak; the Bugis in almost all areas; the Minangkabaus in Negri Sembilan, Melaka and Pahang; the Chams in Terengganu and Pahang; and the Orang Laut along the coasts of Johor had all intermingled and left cultural imprints. A new race of people had emerged, representing an amalgamation of these groups from across the archipelago.

Of particular interest in this period is how the European intrusion affected Aceh in Sumatra, the sultanates in the peninsula that had made up the old Melaka Empire and the Bugis of the eastern archipelago.

By the end of the nineteenth century, virtually all Southeast Asia, except Siam, was divided among European powers. The roles of the indigenous people in trade virtually ceased, except in coastal shipping and in the provision of labor to produce or extract goods for the Europeans. In the nineteenth century, there was a distinct demarcation in the history of Malaya. Prior to this time, the history of the Malays and Malaya could not be divorced from the history of the greater archipelago. The sultanates were not modern states with fixed borders but river and coastal royal courts that came and went with the fortunes of trade and manpower. The domination of the European powers changed the history of the Malay world to a history of the peninsula.

Many forces at work in Europe shaped the motivation for and the nature of European expansion. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there was the rise of the nation state in Europe. Portugal, Spain, England, the Netherlands and France were solving domestic problems and creating strong central governments, governments that could marshal significant economic and military power to achieve national goals outside the home countries. Increasing nationalism also meant that political and economic rivalries were manifest in the dominant European economic system of the time – mercantilism. The system was based on the premise that nation states were in competition for their share of the world’s wealth. Each nation protected its economy by controlling trade and restricting it to its own country and colonies. The idea of “my gain is your loss” and vice versa was bound to lead to conflict.

Another economic force that contributed to Europe’s outward expansion was the commercial revolution. New products created the need for new markets and new sources of wealth. Tea, spices, silk, cotton, tobacco and coffee were increasingly in demand, and fortunes could be made by supplying these goods. At the same time, new forms of business organizations, such as the joint stock company, offered avenues for men in commerce to pool their wealth and embark on large business ventures. Access to these new products was controlled by a pipeline of Malay, Indian, Middle Eastern and eastern Mediterranean merchants. If the western European nations could circumvent these middlemen, there would be unlimited opportunities for their businessmen and monarchs.

Portugal, a relatively small country of a little over a million people (most of whom were farmers and fishermen), had a great impact on the world in general and Asia in particular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which was strongly motivated by dreams of wealth and religious fervor. Portugal’s goal was to monopolize the trade in spices from the archipelago and luxury goods from China and India.

Its motivation was also aimed at those who controlled the trade – the Muslims. The Portuguese were tough, nationalistic and used to adversity. Their battle for survival as a state had been against the Muslims, and the last of the Islamic invaders had only been expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492. These battles, coupled with memories of the crusades, fueled their desire to punish the Muslims and convert the people of the East to Christianity.

The Portuguese possessed the means as well as the motivation to embark on this endeavor. In their voyages to trade with the East, they made dramatic strides in naval technology. As a result of new shipbuilding methods and sail design, the Portuguese could sail closer to the wind, and their ships had more speed and maneuverability than those of their European competitors. New navigational techniques also freed their dependence on the prevailing winds. New advances in naval gunnery provided deck-mounted cannons that had a longer range and better accuracy than those of the Indians and Malays.

Much of this advancement in maritime prowess can be attributed to the vision of Prince Henry, the Navigator. Through his efforts, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, and Vasco da Gama reached India in 1498. These voyages paved the way for the development of the Portuguese trading empire in the sixteenth century.

Sailors in the Spanish expedition (1519 to 1522) led by Ferdinand Magellan are usually credited with being the first to circumnavigate the world. In actual fact, the first man to circumnavigate the world was a Malay.

Magellan was originally from Portugal, and his early seafaring career was in service to the Portuguese crown. While in Portuguese Melaka, he purchased a Malay slave from the southern Philippines, whom he called Enrique.

Enrique accompanied Magellan back to Europe, where shortly after his return, Magellan switched allegiance to Spain and renounced his Portuguese citizenship. In Spain, he convinced the crown to back an expedition to the Spice Islands by sailing west from Spain, thus circumventing the intent of Treaty of Tordesillas, which was to keep Spain out of Southeast Asia.

When Magellan arrived in the Philippines, Enrique became the first person to circumnavigate the world. Magellan was ecstatic because arriving at Enrique’s homeland was proof that the world was indeed round.

Enrique was invaluable to Magellan’s efforts at converting the people to Christianity and conquering the area because he could converse with the natives. After Magellan’s death at the hands of enraged islanders, who were retaliating against the mass rape of their women, the remainder of the Spanish crew escaped. Of the 60 men who had fought the islanders, only Enrique and two others survived.

Magellan had promised Enrique freedom after his death, but the new captain refused to let him go. He jumped ship and remained in the Philippines.

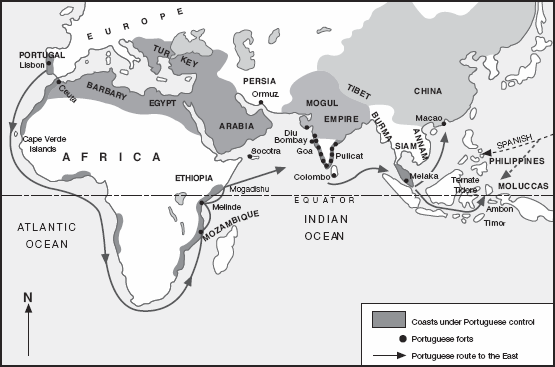

The Portuguese Empire in the sixteenth century.

The Portuguese wanted to establish a series of naval fortresses from Lisbon to the Spice Islands in the archipelago in order to dominate the sea lanes, control the East-West trade and deny alternative routes to those trying to avoid their system. They established ports of call in the Cape Verde Islands, Angola and Mozambique along the coast of Africa, a fortress at Socotra to dominate the entrance to the Red Sea and a base at Ormuz to guard access to the Persian Gulf. On the western coast of India, they seized Goa, which became the headquarters of their trading empire in the East as well as a source of Indian goods, mainly cotton textiles, to trade with Southeast Asia.

The capture of Goa in 1510 was a gruesome example of the religious dimension of Portuguese expansionism. Admiral Albuquerque put its entire Muslim population to the sword, butchering thousands of people. He then created a Christian population by marrying non-Muslim Indians to Portuguese sailors from his fleet. As a result, most Arab traders fled the western coast of India.

Portuguese ships first called on Melaka in 1509, asking for trading privileges and the right to build a fort. The Malays attacked the Portuguese fleet and seized some twenty sailors. The Portuguese responded two years later when Alfonso de Albuquerque returned with a much larger fleet and a thirst for vengeance. Although the Portuguese were outnumbered 25 to 1, they won because of their superior artillery and the internal weakness of Melaka. Albuquerque’s guns destroyed all the Muslim shipping in the harbor. The ruling family of Melaka fled east to Pahang and eventually established a new Malay kingdom in Johor and the Riau Islands.

The Portuguese established outposts in the Spice Islands – at Ternate, Tidore, Ambon and Timor – and at Macao in China. Thus, by the middle of the sixteenth century, the Portuguese trading empire stretched from China and the Celebes through Melaka, Galle in Ceylon, India and around Africa to Lisbon, which became the distribution point in western Europe for much of the eastern produce. This great empire brought much wealth to Portugal. To give an example, $45 worth of spices bought in the Celebes could be sold for $1,800 in Lisbon.

However, the Portuguese never fully achieved their original objectives to control the straits, achieve wealth and convert Muslims. Portugal was a small country and its trading empire was too far flung. It was never able to control the straits completely because its navy did not have sufficient ships in the area. As a result, Melaka under Portuguese rule spent most of its history fighting off attacks by the Javanese, the Acehnese and the Johor Malays in 1513, 1537, 1539, 1547, 1551, 1568, 1573, 1574, 1575, 1586, 1587, 1606, 1616, and 1639. They were fortunate that the Acehnese and the people of Johor disliked each other and so did not join forces against Portugal. The Portuguese fortress, A Famosa (The Famous), with its eight-foot walls, made it possible to hold off the attacks until help arrived from Goa or the Spice Islands.

Portuguese Melaka never achieved its goal of becoming a trading center for a number of reasons. The Portuguese had originally intended to recreate the system and services provided by the former sultanate, but Melaka did not attract Portugal’s best and brightest administrators. Most of the Portuguese who went there were military men and soldiers of fortune. The result was a system run by barely literate men that was rife with corruption. As a result, much of the revenue that was supposed to go to the crown and to run the port was mismanaged, and Melaka could not pay its own way. As time went on, rather than enriching the royal Portuguese coffers, it became a liability. Added to this was the inability of the Portuguese to control the Sunda Straits, which meant traders could conduct business in western Java and avoid Melaka altogether.

Given the crusading Christian reputation of the Portuguese, few Muslims were going to trade in Melaka. Muslims from India traded with Aceh, Pasai, Riau and Java. Corruption, inadequate facilities and poor services in Melaka deterred many non-Muslims as well. Melaka became more of a garrison town than a trading center. It was of use to the Portuguese trading system as a port of call and a naval base to protect their shipping and trade. Ships going west from Macao in China with tea and silk stopped there, while Portuguese captains carrying silver from Japan and spices from the archipelago had a safe haven on their way to Goa and Portugal, but Melaka was not the emporium and entrepôt that it had once been.

Finally, Portugal failed to convert people to Christianity; in fact, its efforts were counterproductive. Their ruthless treatment of the Muslims drove them away from Christianity. Islam became a rallying call for those opposed to European intervention, and the faith grew as a result. Great missionaries, such as Francis Xavier, gave of their best in Melaka but left in frustration. The only converts were the wives and children of the locals who married Portuguese sailors and soldiers. The descendants of these people and a few Portuguese words in the Malay language are the only lasting heritage of the Portuguese presence in Melaka.

The impact of the Malay world’s first encounter with a European power was essentially negative. Portugal ended the Melaka Sultanate and its efforts to create greater political and cultural Malay unity. Although Johor would continue the royal lineage of Melaka, the Malay political world was moving toward political fragmentation, which would make the area vulnerable to further European expansionism. The presence of aggressive outside powers, such as the Portuguese, disrupted and dissipated the wealth that the peninsula derived from its strategic position in the East-West trade. Portuguese rule in the area was an omen of things to come.

By the last decade of the sixteenth century, Portugal’s tenuous hold over its Asian trading empire was increasingly apparent to other European trading nations. The Dutch and the English began to challenge its routes and sources, determined to take over the lucrative trade in the East.

Until the coming of the Portuguese, Aceh was a relatively minor state at the northern tip of Sumatra, which survived off preying on ships and the sale of pepper. This Muslim state was one of the main benefactors of the exodus of Muslim traders from the Christian Portuguese takeover of Melaka in 1511. The increase in trade and wealth generated by these traders made Aceh the dominant Malay power in the western archipelago in the century following the fall of Melaka.

Under the leadership of Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah Al-Kahar, who ruled from 1537 to 1568, Aceh combined religious fervor and a formidable military machine to achieve success. Aceh had accepted Islam in the fourteenth century and in the sixteenth century used the religion to unite the Islamic areas of Sumatra. Missionary zeal and the sword converted non-Muslim groups as well, such as the Minangkabaus. Aceh had the most modern non-European military force in the area, with Turkish mercenaries providing advanced gunnery skills. The artillery capabilities of the Turks (who also hated the Portuguese), coupled with fiercely loyal Acehnese, gave Alauddin an awesome military force.

Aceh conquered much of the western coast of Sumatra and controlled the Sunda Straits for a while, offering an alternative route to those who wanted to avoid the Portuguese in Melaka. Acehnese fought the Portuguese for a century, trying to take control of the Straits of Melaka. In the end, they failed to defeat the foreigners, primarily because of the more advanced Portuguese navy and the impregnable fortress at Melaka. Aceh did capture the sultanate of Perak and its tin deposits and dominated Perak for almost a century, thus introducing a new group into the Malay cultural mix on the peninsula.

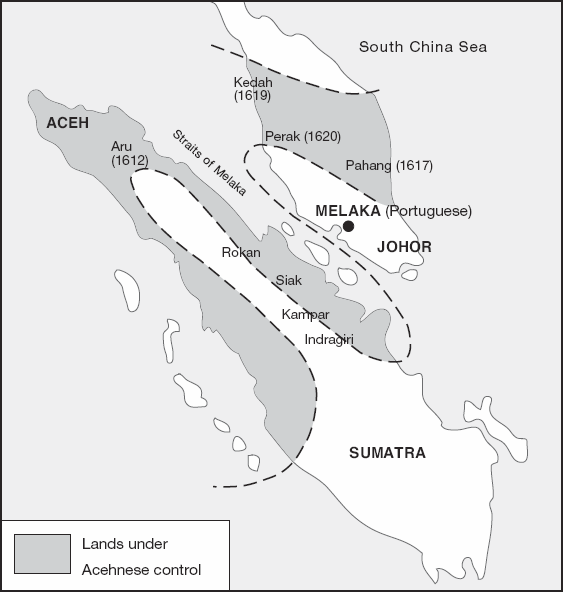

The Acehnese Empire in the early seventeenth century.

Aceh reached the height of its power under the rule of Sultan Iskandar Muda, who reigned from 1607 to 1636. During this time, it extended its control over most of the Malay Peninsula, capturing Pahang in 1617 and sending one thousand of its inhabitants to Aceh as slaves. The Acehnese seized Kedah in 1619 and created refugees of the royal family of Johor by repeated sackings of their capital. All that stood in the way of Sultan Iskandar and the recreation of an empire on the scale of Srivijaya and Melaka was the Portuguese garrison.

In 1629, Aceh assembled an army of twenty thousand men and two hudred ships to conquer Melaka. This was an incredibly large force for a trading empire, and Iskandar threw a large portion of his resources into this battle for the straits. His troops fought almost to the heart of the city, but reinforcements arrived from Goa in time to tip the scales. In the Portuguese counter-attack, the Acehnese suffered huge losses. Estimates by historians on the number of Acehnese killed vary from ten thousand to nineteen thousand – devastating numbers.

This debacle and the wars that preceded it decimated a generation of young Acehnese and forced Aceh’s withdrawal from many of its conquered lands. Although their power was checked, the Acehnese had built a reputation as a strong and self-sufficient people, devout in their religion and fearless in battle. In the nineteenth century, when the Netherlands extended its control over what is known as Indonesia today, Aceh was the last to be subjugated. The Dutch fought a 25-year war with Aceh (1873–1898) and never really established effective control over these people. To this very day, the Acehnese remain a fiercely independent people and continue to resist domination by the Indonesian government.

Although Aceh was the heir to Melaka in terms of power and trade, Johor, in the eyes of many Malays, was the legitimate heir to the lineage of Srivijaya, Parameswara and Melaka. The story of this royal family begins with the last days of Melaka.

Johor River and the Riau and Lingga Archipelagos (1500–1700).

After the Portuguese captured Melaka, Sultan Ahmad and his father beat a hasty retreat to Pahang. Mahmud, having observed his son’s ineptitude in crises with the Portuguese and upset with Ahmad’s deviant and toadying entourage, eventually had him murdered and reclaimed the throne, not trusting the future of the Melaka royal family in Ahmad’s hands.

To reestablish the prestige of his court, Mahmud settled in Riau on Bentan. Like his forefather Parameswara, he turned to the local community, the Orang Laut, for support and manpower. Initially, Mahmud’s plan was to raise an army and retake Melaka. Virtually all the peninsular states had ties through marriage with the Melaka royal family, and there was hope that an alliance among the states, the Orang Laut from Riau and the remnants of the old empire could defeat the Portuguese. Johor would pay a heavy price for this belief.

In the three-way competition for control of the straits and trade in the western archipelago among Aceh, Johor and Portugal, Johor was constantly on the losing end. It has been said that Johor’s capital was burned down so often that the followers of the sultan became construction experts by rebuilding it.

In 1526, the Portuguese burned Bentan in retaliation for an attack by followers of the sultan. The royal court then moved to a site up the Johor River. In 1535, the Portuguese destroyed the new capital. By the 1540s, because of its inability to fight off the Portuguese and Acehnese, Johor ceased to be the heir to Melaka in the eyes of some of the other royal families, particularly in Sumatra. However, its sovereignty continued to be recognized in many parts of the peninsula.

Riau and Johor spent the rest of the century on the defensive, as Aceh grew in power and became increasingly hostile. At one point, Johor made an alliance with the Portuguese, who also wanted to check the power of Aceh. The sultan made a state visit to Melaka – the first member of the royal family to set foot in Melaka since 1511 – to consummate the alliance. However, a successful campaign against Aceh fueled Johor’s ambition, and it attacked Melaka while Portugal was sidetracked by Aceh. In 1587, the Portuguese retaliated, and the royal court moved farther up the river to Batu Sawar.

Aceh occupied the Johor capital in 1613 and took the royal family prisoner. It put the sultan’s half-brother on the throne, but Sultan Hammat Shah proved to be no puppet and removed the royal court into the Orang Laut heartland in the Riau and Lingga archipelagos. In retaliation against his perceived treachery, Aceh pillaged and burned the capital at Lingga. This was, no doubt, one of the low points for the descendants of Parameswara. The sultan went into hiding, and the Johor royal family faced political and economic obscurity.

Johor’s fortunes changed with the arrival of the Dutch because both Aceh and the Portuguese were enemies of the Dutch. Aceh controlled the Sunda Straits, and the Portuguese stood in the way of Dutch trading ambitions. Thus, in 1639, the Dutch joined forces with Johor to attack Melaka. As a result of the fighting spirit of their soldiers and the strength of A Famosa, the Portuguese held out for almost two years until they finally surrendered in 1641.

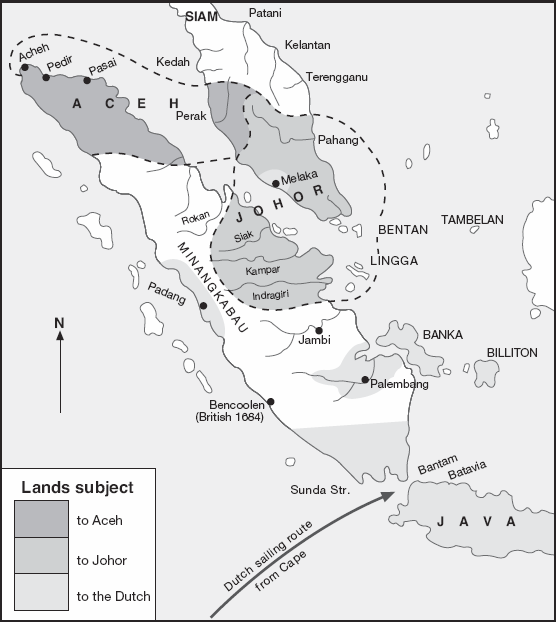

Aceh, Johor, and the Netherlands in the late seventeenth century.

This alliance with the Dutch was a learning experience for the people of Johor. They had planned to reoccupy Melaka after the Portuguese defeat and reestablish the Malay Empire. The Dutch wanted control of the straits and were not interested in Johor’s plans. It began to dawn on the local powers that the Dutch objective was to monopolize trade, and anyone who interfered was bound to feel the wrath of their sea power.

However, the Dutch had little interest in the political affairs of the peninsula other than in Melaka, and as Johor expanded its influence northward, they were perfectly happy to stay out of the way. Friendly relations with Johor were in the interests of the Dutch because of the havoc Johor’s sailors could wreck on Dutch shipping.

As a result of Dutch victory over the Portuguese and the check they placed on the weakening Acehnese, the people of Johor were able to move their capital back to the mainland and reestablish the kingdom along the Johor River under the leadership of Sultan Abdul Jalil Shah II (1623–1677).

Over the next fifty years, Johor was once again the strongest power on the peninsula. It reestablished influence over much of what had been Melaka’s territory and made alliances with sultanates in Sumatra. The Johor River and Riau once again became important entrepôts. Although much of the trade was with the Dutch, there are numerous accounts of a bustling, successful trading economy that was the outlet for Malayan pepper, hardwood, camphor, rattan and tin. That Johor could achieve this after its losses to Aceh and Portugal was because of the system of government inherited from Melaka.

If Johor had not become involved in a disastrous war with Jambi in Sumatra in 1673, it might have remained a prosperous kingdom with economic and political independence. The war was a result of royal marriage politics. The sultan of Jambi pledged his daughter to the crown prince of Johor. The laksamana of Johor, Abdul Jamil, feared that both his and Johor’s power would be diluted by this alliance and preferred that his own daughter marry the prince. The sultan of Jambi took this as a personal slight and an insult to his people and proceeded to raze the capital. Johor eventually won the war but in the process, lost political control over its government. Weakened by the destruction of the capital and in the face of superior forces, the Johor laksamana had enlisted the help of Bugis mercenaries from the eastern archipelago. The Bugis had tipped the scales in favor of Johor, but at the end of the war, they refused to go home. Not having the military power to force them to leave, Johor was compelled to invite into its midst a tough, cohesive people who would dictate the future of the sultanate. Another result of this war was Johor’s loss of control over the Sumatran Minangkabaus who no longer feared Johor’s power.

Johor’s loss of independence occurred during the reign of Sultan Mahmud (1685-1699). A seven-year-old at the time of his ascension to the throne, he was dominated by the family of Laksamana Abdul Jamil, who for all practical purposes ran the country. When Sultan Mahmud came of age, it became apparent that he had some serious personality flaws and was not suitable to be a Malay sultan. He was a sadist and a pervert, as well as a homosexual. It was said that he once used members of his court for target practice when he was trying out a new set of guns. Another time, he was said to have ruthlessly punished the pregnant wife of one of Johor’s leading citizens for stealing fruit from his orchard by having her disemboweled in public.

The sultan posed a problem for the merchants and officials of Johor. They wanted him dead, but Malays believed that the sultan was God’s representative on earth. For commoners to kill the sultan was a threat to the legitimacy of the crown. If they could overthrow the crown, where was the daulat of the sultans? In spite of the dilemma, leaders in the merchant community stabbed the sultan to death in the marketplace.

Although Johor prospered for a short while under Sultan Abdul Jalil Riayat Shah III, who as bendahara had been one of the conspirators, the murder of Sultan Mahmud ended a royal line that stretched back to the divine creation of the Palembang monarchy. His murder weakened the loyalties of many of the people in the area, especially the Orang Laut. Questions were also raised over the divine legitimacy of a ruler. Inevitably other powers began to compete for the power vacuum that existed.

Two of the largest ports in the world today are Singapore and Rotterdam. By collecting and selling the goods of other countries, both have used their geographical locations to become centers of trade. Rotterdam sits at the mouth of the Rhine River, which flows from the North Sea through the heart of western Europe to Switzerland. The Dutch made their living on the trade that flowed up and down this river. They also worked as coastal traders and fishermen in the Baltic Sea and the English Channel. The sea and trade were vital aspects of their economy.

In the sixteenth century, the Netherlands was part of the Catholic Spanish Empire. When the Protestant Reformation took place in Europe, many Dutch left the Catholic Church and became Protestant, which in turn led to a Dutch rebellion against Spain. In 1580, the kingdoms of Spain and Portugal merged, and the Spanish crown, in an attempt to bring the rebellious Dutch in line, closed the port at Lisbon to Dutch traders and shipping. This threatened the economic lifeblood of the Netherlands. While the Portuguese and Lisbon were the source of products from the East, the Dutch were the distributors of these products in western Europe. The ban on access to some of their most lucrative trade became a primary motivation in the Dutch desire to cut out the middleman and seize control of the commerce from the East, especially that of the archipelago.

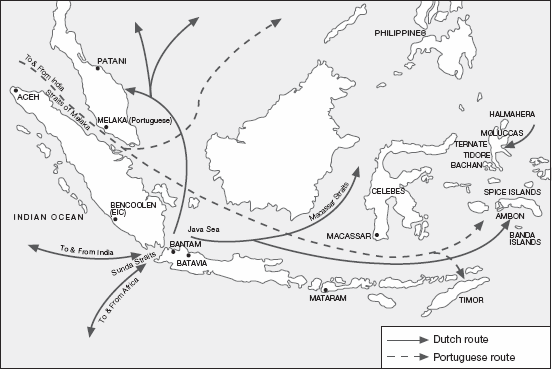

Portuguese and Dutch trade routes in the seventeenth century.

Many Dutch sailors had traveled with the Portuguese to the East and had learned Portuguese navigational and sailing methods. During these voyages, the Dutch had also observed that Portuguese control over their trading empire was weak. The secret was out – Portugal was vulnerable and unable to defend its far-flung empire. This knowledge and Dutch advances in naval technology gave them the tools to challenge Portuguese trade between Europe and Asia. Thus, by the end of the sixteenth century, a mixture of nationalism, economic necessity and maritime knowledge created a new player in the trade of the archipelago – one much more formidable than the Portuguese.

The vehicle for the creation of Dutch trading dominance was a joint stock company called the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The Dutch movement to the East was thus financed and controlled by private investment, although the Dutch government granted it a monopoly on the trade with the East and the virtual powers of a government. The company had the power to make laws, appoint judges, set up courts and police forces and administer any territories it seized. The VOC also had the authority to establish an army and navy. By the second half of the seventeenth century, it had an army of 10,000 men and an armed fleet of hundreds of merchant and naval vessels and was virtually a law unto itself. In today’s world, a comparison would be to give a major oil company total control over all the oil coming out of the Persian Gulf.

The VOC realized that the key to profitable trade meant controlling the supply of produce at its source – not just controlling the distribution, but controlling the amount placed on the market. The Dutch wanted to make money, not save souls or punish Muslims. By avoiding the mistakes of the Portuguese, the Dutch were able to make deals with local Muslim rulers and interfere in local battles over thrones without the Muslim/Christian issue. In Java and Sumatra, Dutch military support became important in tipping the scales in favor of local competitors for royal power.

However, it did not take long for the locals to realize that the Dutch monopoly on trade was detrimental to the archipelago’s economic health. As the seventeenth century progressed, Dutch policy became increasingly ruthless. Local leaders and populations in the Celebes and Moluccas who did not cooperate with Dutch demands faced fearful consequences. On Lontor, the entire population was wiped out because of its defiance of the Dutch; on Run, the local population was sold into slavery. In Ternate in 1650, Bachan in 1656 and Timor in 1667, native spice crops were burned because too much had been grown, and the surplus could not be absorbed by the Dutch. As demand for coffee and sugar increased, local populations were forced to grow them in lieu of traditional crops or, in some cases, food crops.

Control of the sea lanes was a necessary ingredient in the VOC’s ambitions. To this end, the Straits of Melaka posed a problem because Aceh was at the northern entrance, Johor was in the south and the Portuguese were in Melaka. The Dutch sidestepped the problem by utilizing the Sunda Straits as a shipping route and avoiding the Portuguese navy. They established a trading center in the western part of Java in 1619 – Batavia – creating a commercial collection point close to the source of the product they were most interested in – spices. Batavia was built on a Dutch model, a bit of Europe in Southeast Asia, and was meant to be the new Melaka.

The Portuguese and the local powers, especially the Javanese, fought tenaciously throughout the archipelago, but the Dutch slowly established their supremacy in Ambon and the Banda Islands (1621), Macassar (1667), Ternate (1677), Mataram (1682) and Bantam (1684). However, as long as the Portuguese held Melaka, Dutch control of the spice trade was under threat. With the help of Johor, Melaka was taken in 1641.

As a result of Dutch occupation, Melaka’s role became negative – to deny its use as a port to anyone and to force trade south to Batavia. Although the Dutch still had to fight the local powers for control of the straits, they had negated the straits’ importance as a major highway of trade. It is ironic that the only non-Dutch power to use Melaka after its fall was Portugal, which continued to need a port of call between Macao in China and Goa in India. A secondary role for Melaka under the Dutch was as a collection point for tin and to enforce the Dutch monopoly on the produce coming out of Perak, which was not very successful. Thus the Melaka of Parameswara, Mansur Shah and A Famosa became a secondary naval base in the VOC trading empire, a colonial backwater.

In many ways, the seventeenth century was a Dutch century in the East Indies. The VOC made fabulous profits, and the people who worked for them in the East led luxurious lives, with slaves, beautiful homes and standards of living far beyond what they would have enjoyed in the Netherlands.

Except for a few buildings in Melaka today, there is little evidence that the Dutch spent 150 years there. The true Dutch legacy in the history of Malaysia was its impact on the Malay Mediterranean as a whole. As a result of Dutch interference in the economy, the lives of large numbers of people in the Malay cultural world changed. There were serious reductions in living standards as a result of Dutch policies and profits. Others, such as the Bugis, were excluded from their traditional trading patterns, and there were large-scale migrations throughout the archipelago caused by the Dutch. The Malay Peninsula and Borneo were the eventual recipients of many of these displaced peoples. The Dutch also began a process, which over the next couple of centuries, forced many in the archipelago away from their traditional seafaring occupations to agricultural pursuits. Outgunned and outmaneuvered, farming became an attractive option.

In the eighteenth century, the political life of the peninsula was dominated by the Bugis. This group of people had traditionally played a key role in the spice trade of the eastern archipelago. Skilled sailors, boat builders and traders, they were adversely affected by European domination of the trade of the area and by the political problems caused by interference from these outside powers. As the Dutch increased their power and influence, many Bugis migrated west, and their participation in trade declined. Political refugees were also forced to flee west because of civil wars that had erupted as a result of Dutch manipulations of local rivalries.

In the seventeenth century, many displaced Bugis had begun to sell their mercenary skills. As ruthless fighters in the employ of the Portuguese, the Dutch and later the kingdoms of the western archipelago, the Bugis were feared by all. Their prowess as fighters was partially due to their knowledge of modern western weaponry, but more importantly because they operated as organized military and social units that had clear lines of leadership and group loyalty. They literally brought their government with them as they migrated, and each group was a part of a larger Bugis culture from which it could draw assistance. It is estimated that, if necessary, the Bugis could mobilize over twenty thousand men from their bases in Selangor, Riau, Borneo and the Celebes.

A final reason for their success was that they were willing to work within the local political institutions. For example, in Johor, they operated as powers behind the scenes and maintained the traditional structure of the sultanate and its symbolic position in the eyes of the local inhabitants.

In the eighteenth century, a well-connected series of Bugis settlements stretched from the Celebes to the Straits of Melaka. In the Malayan area of the archipelago, Bugis settled in uninhabited areas of Selangor and Linggi. Others signed on as soldiers in Johor and set up in the Riau and Lingga archipelagos. It is from their bases in these areas that they rose to power in the Malay sultanates.

By this time, the battle for control of Johor had passed from internal competing factions to outsiders. The decade and a half of peace and prosperity after the assassination of Sultan Mahmud ended with a battle between the Bugis and the Minangkabaus for control of the Malay kingdoms in the peninsula.

In 1716, a Minangkabau prince from Siak in Sumatra, Raja Kecil, claimed the Johor throne, saying that he was the son of the last legitimate sultan – Mahmud. His somewhat farfetched story was that his mother smuggled him out of Johor, and he was born after his father’s murder. His claim was backed by his origins in Minangkabau and the support of its religious leaders, who traced his legitimacy back to the three legendary princes who were the heirs to Malay royalty. Raja Kecil rallied the support of many Orang Laut and Johor subjects who felt that Sultan Abdul Jalil’s claim was illegitimate. Raja Kecil invited the Bugis from Riau to join him in restoring his family to the throne, but then staged a preemptive strike on Johor’s capital. Raja Kecil outwitted himself because the Bugis felt that the coup was an act of treachery, and a five-year war ensued. The Bugis gained control of Johor and put the son of Abdul Jalil on the throne, which was meant to give the government a veneer of legitimacy while the Bugis filled the key positions of power. An eighteenth-century Bugis chronicle observed, “The sultan is to occupy the position of a woman only; he is to be fed when we choose to feed him; but [the Bugis] is to be in the position of a husband; his will is always to prevail.”

How much the Bugis cared about the day-to-day affairs of government in the peninsula is questionable. What they really wanted was a base in Riau free from interference from Johor so as to extend their power and influence throughout the region. They gained power by intervening in the competition for the thrones of the sultanates, which by then had taken on epidemic proportions. In Kedah and Perak, the Bugis and Minangkabaus sided with competing factions for control of the governments, and in the ensuing warfare, the Bugis came out on top.

Selangor was an exception to the Bugis practice of ruling through puppet sultans. In the eighteenth century, the interior of Selangor was virtually uninhabited, and when the migration of Bugis from the east took place, many settled there. During the period of conflict between the Minangkabau and the Bugis, Raja Kecil invaded Selangor. The Bugis eventually drove the Minangkabaus out in 1742 but realized they needed to establish solid governments in these settlements. To that end they set up the sultanate of Selangor, only this time a Bugis family held the title. Prince Raja Salehuddin began a dynasty that has passed down directly to the present sultan of Selangor.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Bugis had established an impressive area of control that included Johor, the allegiance of Pahang and the strategic Riau Islands, Kedah (the largest rice growing area), Perak (the largest source of tin), Selangor (a base on the Straits of Melaka) and the Bugis homeland in the Celebes. The only local threat was the Minangkabaus, but they had become somewhat docile after being defeated so often by the Bugis.

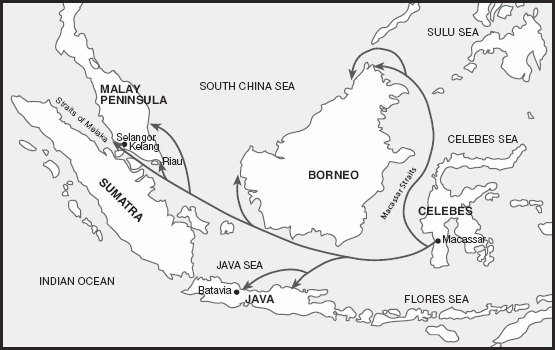

Routes showing Bugis migration.

Eventually, the Bugis came into conflict with the Dutch because their goals were the same – to dominate the trade and commerce of the archipelago. As long as the Bugis stuck to the political infighting of the peninsular sultanates, the Dutch had little interest in clipping their wings, but by the middle of the eighteenth century, the two powers were on a collision course.

Demand for tin in Europe and China had risen rapidly, and Bugis control over most of the tin-producing areas in the peninsula threatened Dutch access to and control of this lucrative commerce. The Bugis/Malay entrepôt in Riau was a thriving concern, which drained trade away from Batavia. What the Dutch saw as Bugis piracy also contributed to increased confrontations. At heart, most of the Bugis were warriors, and as Dutch shipping and trade increased, their ships were too tempting to ignore.

The combination of commercial competition and mayhem on the high seas drew the Dutch into armed conflict with the Bugis. In the 1750s and 1780s, actual warfare took place, culminating with a Bugis attack on Melaka in 1784. The Dutch victory and the ensuing counterattack seriously curtailed Bugis power and influence. Caught between the Dutch fleet and the walls of A Famosa, the Bugis incurred heavy losses. After their victory at Melaka, the Dutch attacked Selangor and forced the Bugis sultan to flee temporarily to the eastern coast. They then attacked and occupied Riau, taking over the administration of the government. With the end of Bugis power in the peninsula, there was no longer a dominant local power. It is ironic that although the Dutch successfully destroyed Bugis power in the area, it was the British who benefited from it.