6 |

THE MALAY PENINSULA UNTIL 1874 |

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 put an official stamp of approval on European control of archipelago trade. The treaty symbolized the end of active Malay participation in international trade, a tradition that stretched back centuries to the empires and nation states of Selangor, Terengganu, Riau, Johor, Melaka, Srivijaya and Kedah. Trade to and from the Malay Peninsula was subsequently dominated by foreigners from outside the archipelago and funneled through the ports of the Straits Settlements for the benefit of outsiders. The power and prestige that Malay rulers and traders had derived from their positions astride one of the world’s most important trading routes were severely curtailed. Instead of partners and participants, the Malays became spectators. Historian Ian Proudfoot claims that the establishment of Singapore stuck “a dagger in the heart of Malay feudalism.” The treaty also symbolized international acceptance that Britain would determine the future of the Malay states in the peninsula.

The relegation of the people of Malaya to minor positions in international maritime trade created a fragmented and fragile nineteenth-century Malay political world. Intrigue and shifting political loyalties had been hallmarks of Malay history, but the rules of the game were changing. The traditional power and independence of the Malay sultanates had been based on three factors: their ability to obtain revenue from the trade that passed through the straits and up the rivers to the royal capitals; their ability to create alliances with other states and groups along the trade routes and with those who used the trade routes, such as the Chinese and Indians; and their ability to mobilize manpower to control the revenue and those alliances.

In the post-1824 world, the scope of the royal courts to wheel and deal in the ways of their forefathers eroded significantly. The Dutch moved steadily to establish political control over the Malay states in Sumatra. Politically, this effectively cut off the peninsular states from Sumatra and Java, areas that had ties of history and blood that went back to Srivijaya. The treaty also isolated the peninsula from its ties with Riau, which had been part of the Johor Empire and had been a fertile source of Bugis manpower. The Indians and Chinese were no longer viable sources of support for the Malays because Europeans dominated the trade of both India and China.

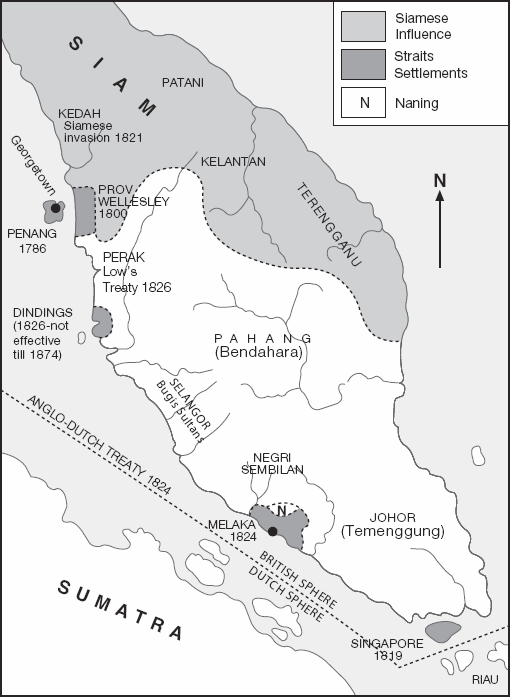

Malaya in 1826, showing the division of the Malay Mediterranean by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. The islands near Dindings were ceded to the British in 1826 and were part of the Straits Settlements. Dindings was not used by the British, except as a small base for the suppression of piracy, and was returned to Perak in 1935.

The Malay states still had produce the world wanted, but it was reaching world markets through mostly non-Malay coastal traders, who traded in the British settlements. The weakening of their maritime power base also made it difficult for the coastal royal courts to exercise control over the sources of the produce in the interior of the country. After the establishment of the Straits Settlements and the demarcation of the archipelago into Dutch and British spheres of influence, no Malay port in the peninsula achieved any level of importance until the latter half of the twentieth century.

In the past, when Malay leaders faced political adversity or declines in their fortunes, they had turned to preying on ships at sea as a means of survival until they or their descendants could rebuild alliances and regain sufficient power to stage a comeback. For a while in the nineteenth century, the Malays attempted to do this again, but this avenue was eventually blocked by superior Western military power and technology. The presence of the Royal Navy in the straits was no doubt important in reducing attacks on trade. In any direct confrontation, the firepower of British ships was an awesome deterrent. Although the river mouths and mangrove swamps gave great cover to small Malay crafts, which could outmaneuver the larger naval vessels, this changed with the arrival of the steamship in the middle of the century.

The impact of a steamship on those who had never seen one is aptly portrayed in the story of the HMS Diana. In 1837, a group of Malay pirates saw smoke coming from the ship as it entered Malayan waters and thought it was on fire. They mounted an attack on what they thought was a crippled ship, but instead the flotilla was destroyed by the Diana.

The political situation in the Malay Peninsula was in considerable flux. The structure of the old feudal Malay states of Perak, Selangor and Negri Sembilan was weak, and until formal British intervention in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, there appeared to be few viable alternatives to disorder and political instability. Politics in the northern states was also complicated by Siam, which emerged from its eighteenth-century wars with Burma strong, united and aggressive. The Malay states had to contend not only with the consequences of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty but also with a northern neighbor that wanted to dominate them. Johor was an exception to this instability because of its strong leadership and its proximity to Singapore.

The majority of the Malay population experienced little change in this century. Life in the kampungs under village leaders continued to revolve around subsistence agriculture and fishing. The peninsula remained sparsely populated, with a Malay population of about 300,000 people in the 1830s. While the rural population grew during this period as a result of further emigration from the archipelago, especially from Sumatra, the growth did not represent a significant source of political support or manpower that would restore the fortunes of Malay rulers.

The villages were portable and re-buildable. Villagers had few material possessions and limited loyalty to their sultans. Thus, if the royal demands were too great or economic times were bad, the people moved on. For instance, when Kedah went to war with Siam in the early nineteenth century, a large part of the rural population simply moved to the relative security of British-ruled Province Wellesley, reestablished their villages and continued their agricultural pursuits. In the second half of the century, when famine hit Kelantan, a large number of farmers moved to the south and west of the peninsula.

The problems of the Malay leaders were compounded by the nature of British policy for the first three quarters of the century. Malaya fell within the British sphere of influence, but until 1874, the British pursued an ambiguous policy of non-intervention. While the British revolutionized the Malay political world by controlling the straits and trade, they did not want to interfere in the internal affairs of the peninsula or allow others to do so. This was an unrealistic policy because the instability could not always be ignored, and from time to time the British were forced to interfere.

The non-intervention policy created a political limbo, in which the Malays did not know whether the British would assist in a crisis or ignore it. Additionally, Malaya, like the Straits Settlements, had to deal with the fact that until 1858, power was held by a private company, the EIC, whose policies were formulated in India. To the EIC, the purpose of a British presence in the area was to keep the shipping lanes open, to provide ports of call for the India-China trade and to obtain produce that could be used in trade between these two areas. Any involvement in the affairs of the Malay states ran counter to the interests of the company, especially if it incurred expenses that could affect its profit margins.

An example of the heavy cost of interference was the Naning War of the 1830s. Naning was an area adjacent to Melaka settled by the Minangkabau. To call it a state would be a misnomer. It was a collection of villages stretching over an area of about 518 square kilometers (200 square miles) and owed allegiance to a dato penghulu (hereditary chieftain). In the early days of the Dutch occupation of Melaka, Naning had accepted the control of the VOC government and paid a tax amounting to 10 percent of its crops to the Dutch. Over time, the Dutch stopped collecting the tax because it cost them more to enforce payment than it gained in actual revenue.

As time went on, the people of Naning and other Minangkabau polities in what is now the state of Negri Sembilan came under the control of the Johor Empire. Naning remained a vassal state until the latter half of the eighteenth century. As Johor began to lose influence, a situation developed in Naning that was typical of the political problems faced by the Malay states at that time. Because of the lack of any kind of central control, political leaders of small districts began to assert individual authority. In Naning, Abdul Said, the hereditary chieftain, took on the trappings of Malay royalty, passing out noble titles and assuming the divine authority claimed by traditional Malay courts.

Given Naning’s insignificance, Abdul’s independent stance would probably not have posed much of a problem, but an EIC civil servant, sifting through Dutch records in 1827, discovered the old connection with Melaka. The civil servant made a case to Governor Robert Fullerton that Naning should be considered part of Melaka’s territory and pay taxes accordingly. Fullerton accepted the claim and its vastly inflated promise of $4,500 a year in taxes and pushed for British control over Naning. Abdul Said rejected the argument with good cause, considering that the relationship had not been acknowledged for 150 years. Problems of “face” developed on both sides. Abdul Said refused to give up his independence, and the EIC did not like being defied by a relatively minor Malay leader.

At this point, the nature of EIC rule came into play. For a couple of years, the argument went back and forth between EIC headquarters in India and its representatives in the straits. Abdul Said misread the inefficiency of the EIC as lack of will and decided to dig in.

Eventually, in 1831, 120 EIC troops were sent to collect the tax. The state had no roads, and the British Indian troops became bogged down in guerilla warfare in jungle tracks and lanes between rice fields. In the end, they were forced to withdraw, giving Abdul Said a great victory. Embarrassed, the EIC then sent in a military force amounting to about a third of the entire population of Naning, as well as enlisting the assistance of other Minangkabaus who wanted the British as allies in a local dispute, and ended the year-long war. The conflict is a vivid example of Malay leaders who did not tamely acquiesce to the imposition of British control over their land and independence, a fact further borne out by later violent reactions to British rule in Perak and Pahang.

Abdul Said was captured and forced to live in Melaka on a pension that was far greater than any potential tax revenue from Naning. The British treatment of Abdul Said gained them respect in the eyes of some Malays. To them this was a civilized way to treat the loser in a power struggle.

The campaign cost the EIC $600,000 to obtain a tax revenue that was worth some $600 a year. The EIC directors in London and India, instead of seeing the war as the result of bungling officials, saw it as evidence of why they should stay out of local affairs. They were interested in profits, not people, and were not even satisfied with the Straits Settlements because the administrative costs were greater than the tax revenue. Professor L. Mills called this a policy of “hara-kiri” because Britain ignored the opportunity to extend its influence and trading empire.

A final reason the EIC wanted to stay out of the affairs of the Malay states was to maintain friendly relations with Siam, which claimed authority over Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu. The EIC felt that any intervention in the northern states could lead to a costly military confrontation with the Siamese. Also, the company felt there were greater opportunities for trade with Siam than with the Malay states.

Many of the British traders in the Straits Settlements argued vigorously that the potential for profit from the Malay states was sufficient to support intervention and that becoming involved in Malay affairs was inevitable. For example, Singapore’s trade with the eastern coast of the peninsula alone was greater than the EIC’s trade with Siam and remained so until the abolition of the company in 1858.

Nevertheless, the EIC and the Siamese negotiated the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1826 (Burney’s Treaty), which recognized Siamese sovereignty over Kedah and Siamese influence in Kelantan and Terengganu. In return, the Siamese gave up claims to other parts of the peninsula and agreed not to interfere in the affairs of the other Malay states. The Siamese also granted the British trading privileges in the northern states and in Siam. Given Siamese aspirations in the peninsula, the treaty was unrealistic. The attitude of the Siamese was that if the British refused to intervene in the affairs of the Malay states, it left the door open for them to do exactly that.

The Anglo-Siamese Treaty sent the northern Malay states down a different path from that of the rest of the peninsula. Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu spent the next seventy-five years evading Siamese control over their affairs. Islam, the Malay language and Malay culture were unifying factors in the face of Siamese attempts to dominate the people and draw them into a Siamese/ Buddhist state. These states thus avoided the social dislocation that came with the economic development and immigration caused by British influence in other parts of the peninsula. As the rest of the peninsula was developed and made part of British imperial commerce, the northern states became insular and self-reliant.

In the early twentieth century, the British renewed their interest in these states and eventually brought them under their control, but the seventy-five years the states spent under Siamese control had a marked impact. Because they did not participate to any great extent in the nineteenth-century economic development of the peninsula, the northern states retained their traditional Malay culture. The states did not draw many immigrants, and as a result, their societies were fairly homogenous. There were few urban centers, and they remained, with some exceptions, court and kampung societies.

After 1858 and prior to the official reversal of policy in 1874, the British government found it difficult to follow a consistent policy for a number of reasons. First, it was difficult to maintain a hands-off policy in those areas that were in the immediate vicinity of the Straits Settlements, as problems could spill over and spark off reactions. Second, events elsewhere in the peninsula could also affect British economic interests and those of the inhabitants of the Straits Settlements. Finally, it was difficult to control the actions of the British officials in the Straits Settlements because of the distance between the men implementing the non-intervention policy and those who formulated it in India and London.

Kedah is an example of how proximity to the Straits Settlements made it difficult for the British to follow a consistent policy of non-intervention. In the eighteenth century, Kedah had been under the political influence of Siam. It had paid an annual tribute in gold to Siam, but for the most part, the Siamese let it run its own affairs. In 1786, Sultan Abdullah, fearing the Siamese would increase control over Kedah, had offered Penang to the EIC in return for protection from Siam. The officials in India rejected the request for protection but kept Penang.

In the early nineteenth century, Sultan Abdullah’s fear became a reality. Five years after his death, Abdullah’s son Ahmad Tajuddin won the throne with the help of Siam. The Siamese, looking for wealth and allies in their conflict with the Burmese, called in the debt by asking Ahmad to invade Perak so Siam could control its rich tin deposits. Sultan Ahmad appealed to the EIC for help. The British in India refused despite the fact that there was significant support in Penang for intervention because Kedah was an important source of food for the island.

Without fear of a British reaction, Siam invaded Kedah in 1821. The sultan fled to Penang. Villages and crops were torched, women were raped and homes were looted. Thousands of refugees poured into Province Wellesley and Penang, forming the nucleus of troops that would fight a holy war to recapture their state from the Siamese.

Much of the warfare was hit-and-run in nature, but on at least three occasions, the EIC intervened on the side of the Siamese, while a large amount of financial and material support for the Malay invasion came from the British and Chinese business community on the island. In 1831, about 3,000 Malays crossed the border into Kedah and forced the Siamese garrison to flee. In the ensuing Siamese counterattack, EIC ships blockaded the coast to keep the rebels from being re-supplied by sympathizers in Penang.

After the Siamese put down the revolt, Sultan Ahmad was forcibly moved from Penang to Melaka because he had not informed the British of the Malay attack and also to remove him as a rallying point. In 1836, he assembled another force in Perak, but the EIC sent warships that destroyed his fleet and dragged him back to Melaka. A repeat of the 1831 invasion took place in 1838 when a force of Kedah refugees from Province Wellesley supported an uprising against the occupiers. Once again, they defeated the Siamese army stationed there. As in 1831, they did it with the support of the Penang mercantile community. When the Siamese counterattacked to prevent the rebels from obtaining reinforcements and arms, the EIC assisted by blocking the coast.

The struggle ended in 1842 when British diplomats took advantage of Siam’s war fatigue and Sultan Ahmad’s desperation to hammer out a peace settlement. The Siamese withdrew their military forces from Kedah and restored Ahmad to his throne. The price Kedah paid was that that part of the state bordering Siam was sliced off to create the state of Perlis and another part was annexed by Siam. Both Ahmad and the new royal family of Perlis agreed to be Siamese tributary states.

Three decades of “non-intervention” by the EIC had far-reaching consequences on the sultanate, which had become smaller and impoverished. It took close to 30 years for Kedah to recover from the effects of the war, in part because its entrepôt trade was controlled by the British and Chinese in Penang. The royal family’s primary source of income was the yearly payment they received from the EIC for ceding Penang and Province Wellesley. The end result of non-intervention was that the royal family was paid by the British to be a vassal state of Siam, a far cry from the sultan’s intentions when he made the original deal with Francis Light.

Johor is another example of a Malay state that drew British interference in its affairs because of its location near one of the Straits Settlements. In the original deal that Raffles made to obtain Singapore, the island was administered by the temenggung of Johor, who handed over Singapore for a yearly payment. In order to give the agreement the necessary legal trappings, the EIC installed Prince Hussain as the sultan of Johor. He too received a yearly payment, although everyone, including the other Malay rulers, knew that Hussain was a sultan in name only.

When the temenggung died in 1825, his son Ibrahim, an able and ambitious man, assumed the office. He ingratiated himself with the British by assisting with their efforts to eliminate piracy, which was not hard to do because he was an important backer of a group of these marauders. By withdrawing his financial and political support, he put them out of business.

Ibrahim and his son, Abu Bakar, were forward-looking men and realized that their fortunes and those of their state could be best furthered by developing the commercial potential of something they had plenty of – inexpensive land. To this end, Ibrahim developed a system in which the Chinese from Singapore were given land grants to develop pepper and gambier plantations in the interior of Johor.

Ibrahim was careful to retain a significant degree of control over the Chinese ventures. Each plantation had a kangchu (headman) who was responsible for his community. The contract to farm was renewable and was between the kangchu and the ruler. It could be withdrawn if the Chinese leader did not keep the peace. The Chinese involved were dominated by one dialect group – the Teochews – and only one secret society was allowed to operate. When Abu Bakar succeeded his father, he brought two Chinese onto his advisory council, further cementing the cooperation that existed between the ruler and the immigrants. By 1870, about one hundred thousand Chinese lived in Johor. This arrangement was one of the reasons why Johor did not go through many of the painful nineteenth-century political adjustments that some of the other states experienced.

Ibrahim’s economic good fortune soon drew the jealousy of Sultan Ali, the heir to Raffles’ puppet prince, Hussain. Ali and his family had been living in Singapore, and for reasons ranging from high living to poor judgment, he had fallen into serious debt. Ali asked the EIC government to recognize his position as sultan and give him a share of the state’s wealth. Temenggung Ibrahim wanted nothing to do with this arrangement, and he expelled Ali’s supporters from the state.

The British were faced with a dilemma. Since the breakup of the greater Johor Empire, the temenggung, for all practical purposes, had become the ruler of Johor. Ibrahim was doing a good job, had many friends among the Singapore merchant community and was willing to accept British advice. On the other hand, Sultan Ali was their creation. He had a legal right to rule according to the deal Raffles had struck in 1819. An open conflict between the two would threaten the stability of Johor.

The issue simmered for over a decade. Finally, in 1855, Governor William Butterworth brokered a deal between Ali and Ibrahim. Ali was proclaimed sultan, given the district of Muar to rule and paid a yearly stipend by Ibrahim. In return, Ali gave up all rights to involve himself in the affairs of Johor and recognized Ibrahim and his family as the legitimate rulers of the state. In 1868, the British government gave Ibrahim the title of maharaja. After the death of Sultan Ali in 1877 and Abu Bakar’s agreement to a treaty of alliance with Britain in 1885, the British recognized Abu Bakar as sultan.

On occasion, commercial interests also caused the British to set aside their stated policy of non-intervention. A case in point was the Pahang Civil War that took place in the east coast states of Pahang and Terengganu between 1858 and 1863.

Terengganu had been part of the old Melaka/Johor Empire until the early eighteenth century, when a member of the Johor royal family, Zainal Abidin, established an autonomous state and proclaimed himself sultan. The state prospered from the export of pepper and gold, as well as the weaving of fine Malay textiles and boat building. Late in the century, Terengganu fell under the influence of Siam but experienced little interference in its affairs. While the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1826 viewed Kedah as an actual province of Siam, Terengganu and Kelantan to the north had significant degrees of independence.

Although it was a trading state, Terengganu did not suffer a dramatic upheaval when foreigners took over much of the trade because it actually produced something – textiles and ships. In fact, its textile industry grew as a result of the introduction of British manufactured textiles. The weavers of Terengganu made high quality cotton/silk sarongs that were used by Malays for special occasions. Inexpensive British-manufactured cotton thread reduced the cost of the cloth, making sarongs available to a wider market in the archipelago. Major benefactors of the growth industry were the merchants of Singapore, who supplied the raw materials for the weaving and conducted a thriving trade with the eastern coast in general and Terengganu in particular. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Terengganu was one of the most stable and prosperous Malay states. It did, however, face the ongoing problem of maintaining its independence from Siam.

When the Johor Empire crumbled in the early nineteenth century, Bendahara Ali had taken control in Pahang, just as the temenggung had in the state of Johor. He ruled Pahang until 1857, and established close commercial ties with Singapore and its merchant community. After his death, his two sons, Tun Mutahir and Wan Ahmad, disputed the intentions of their father’s legacy. Before long, the dispute developed into a full-scale civil war. Tun Mutahir, the elder son, received the backing of Abu Bakar of Johor, who because of his close ties with Singapore’s business community, convinced many of them that Britain’s commercial interests lay with Tun Mutahir. Wan Ahmad enlisted the support of Sultan Ali in Muar, who saw an opportunity for revenge against the Johor temenggung. Terengganu and Kelantan also weighed in on the side of Wan Ahmad. Colonel Orfeur Cavenagh, the governor of the Straits Settlements at the time, offered to mediate but was rejected by both sides. Wan Ahmad felt that Cavenagh was biased in favor of his older brother due to the influence of the temenggung and Singapore merchants. Tun Mutahir rejected the help because he was winning the war.

In 1861, Mutahir forced Wan Ahmad and many of his supporters to flee north to Terengganu, and Wan Ahmad continued on to Bangkok. At this point the Siamese became involved. They saw the disorder as an opportunity to exercise greater control over their east coast tributary states and extend their influence farther south into Pahang.

Living in Bangkok at the time was another exile, Mahmud, a descendant of Sultan Abdul Rahman of Riau, whom Raffles had replaced as the ruler of Johor. Mahmud claimed to be the rightful ruler of both Pahang and Johor. Mahmud, Wan Ahmad, Ali and the Siamese struck a deal to turn the civil war in their favor. The plan was to use Terengganu as a staging area and invade Pahang. Upon victory, Mahmud would be made sultan, and, as the bendahara, Wan Ahmad would have control of the government. What Ali would get out of this one can only speculate – if they won, there would then be two claimants to the throne of Johor. Mahmud and Ahmad then proceeded to Terengganu with the Siamese navy.

The Siamese intervention caused great alarm in Johor and Singapore. The merchant community saw it as a threat to their economic interests not only in Pahang, where Siam had never had any influence of note, but also in Terengganu and Kelantan, where an increased Siamese presence would threaten their independence and thus trade with Singapore. Cavenagh demanded that Siam withdraw. The Siamese refused, believing that Cavenagh’s hands were tied by the British policy of non-intervention. In 1862, Cavenagh dispatched a British warship to blockade the coast off Terengganu. When the Siamese still failed to withdraw, he bombarded the fort at Kuala Terengganu. This got the attention of Bangkok, and it eventually acceded to his demands. Ironically, after all the intrigue, the civil war ended in favor of Wan Ahmad because the Pahang chieftains supported him and because Mahmud was dead.

Cavenagh was sharply criticized by the government for exceeding his authority and drawing Britain into the disputes of local Malay rulers. His action, however, was effective. The Siamese were convinced that the British would protect their commercial interests on the eastern coast and would protect Kelantan and Terengganu from direct Siamese interference. The sultan of Terengganu benefited. As long as he paid his tribute every year, he could maintain independence from Bangkok.

The creation of the Straits Settlements and the demarcation of British and Dutch spheres of influence had already begun to undermine the traditional Malay feudal state when two new factors further contributed to political instability in the peninsula – tin and Chinese immigration.

Malaya had been a source of tin for centuries. Tin was a key commodity in the peninsula’s international trade, especially with China, but in the mid-nineteenth century, the demand for tin increased dramatically as manufacturers in Britain and the United States found new uses for it, such as in canning food. Coinciding with this boom in demand was the discovery of large new tin deposits, especially in Perak and Selangor. The development of these tin fields required capital and labor far beyond the resources of the Malay inhabitants, and local chieftains turned to Chinese businessmen in the Straits Settlements for assistance.

The main sources of capital that flowed into the interiors of these states on the western coast were from Chinese merchants and kongsi. A kongsi was similar to a combination of a company and a Chinese dialect association. Men of a clan or dialect group pooled resources, be it capital or labor, to form a cooperative business venture. Bound together by ties of family and culture, they shared the profits based on what they brought into the organization. The economic fortunes of these Chinese ventures were closely tied to the British merchant communities in Penang and Singapore. A combination of the general prosperity of the colonies, business connections between British and Chinese firms and British interests in shipping meant that the Straits Settlements had a tremendous stake in the future of the tin mining industry, not only in mining tin but in selling and transporting it to world markets.

Equally important was tin’s effect on the Malay political system. All of a sudden, Malay leaders in the interior had huge sources of income, and many became wealthier than the sultans and high-level officials in the coastal royal capitals, who had lost their trading resources. The underpinnings of the feudal Malay political system were threatened as these new leaders with revenue and purely local interests challenged the traditional power structure. In the absence of other factors, these changes might have been part of a healthy evolution from feudalism to a modern state. The problem was that at the very time that they were taking place, the Malay states were faced with the influx of huge numbers of Chinese migrants who came to work in the tin mines. The sultanates were in no position to cope with the instability and disorder caused by this population change.

Malaya had been home to immigrants for centuries. For example, the Bugis and the Minangkabaus represented waves of immigrants who came to the peninsula and settled, eventually becoming part of the population. These immigrants had come from elsewhere in the archipelago, and while they were different from peninsular Malays, they shared a common religion, similar languages and the cultural traditions of the archipelago. Their migration was similar to the succeeding waves of European immigrants to the United States. Each new group, be it Irish, Italian or Polish, had enough in common with those already in the United States that by the second or third generation, they had assimilated to a large degree.

A Chinese tin mine of the early twentieth century.

The Chinese migration in the nineteenth century was a totally new phenomenon because the Chinese did not integrate into the local population. The resident Chinese had been in Malaya since the time of Melaka, but they had come in small numbers and had basically adapted. This time they came in large numbers. In Perak, Negri Sembilan and Selangor, they eventually outnumbered the Malays. Through their kongsi, secret societies and dialect groups, they were self-sufficient and had little interest in interacting with the Malays, except when feuds broke out between Malay chiefs, and the Chinese were forced to take sides.

The long-term consequences of Chinese separateness are felt in Malaysia to this day and will be discussed in later chapters. In the short run, the problems the migrants caused were similar to those of the Straits Settlements in the early years. The difference was that in the Malay states, especially Selangor and Perak, the conflicts occurred in areas where the political systems had become ineffective. The repercussions of their rivalries on Malay society eventually helped force the British to reevaluate their policy of non-intervention and take control of the peninsula.

Large deposits of tin had been discovered along the major rivers of Selangor, and by the time Sultan Abdul Samad assumed the throne in 1857, five minor princes were vying for the wealth and power of the state. The weak rule of the previous sultan and the revenue from tin had created fiefdoms, which were aggressively defended by those who held them and coveted by other members of the royal family. Sultan Abdul Samad wanted little to do with these rivalries and withdrew to his palace, where he apparently preferred his opium pipe to affairs of the state.

War broke out over control of Kelang, a tin-producing area at the mouth of the Kelang River, down which tin from the interior traveled. Control of the area had been given to Raja Abdullah by the previous sultan but was claimed by Raja Mahdi, whose father had governed it previously but lost it when his tin ventures went bankrupt. Mahdi attacked Kelang and drove out Abdullah and his backers. Abdullah died soon after, but his sons carried on the war under the leadership of Raja Ismail.

Around this time, Sultan Abdul Samad married his daughter off to the brother of the sultan of Kedah, Tengku Kudin. The sultan created the position of viceroy for Kudin, effectively turning over the affairs of the state to him. Kudin tried to mediate between Mahdi and Ismail, but Mahdi rebuffed his efforts and drove Kudin into Ismail’s camp. Kudin imported fighters from Kedah, and the anti-Mahdi faction recaptured Kelang. The war escalated, with both sides recruiting allies to strengthen their cause.

About the same time, large numbers of Chinese laborers in the newly discovered tin fields in Ampang were fighting among themselves. On one side was the Hai San secret society, which was based in the newly established town of Kuala Lumpur and led by a famous nineteenth century leader in the Malayan Chinese community, Yap Ah Loy. On the other side was the Ghee Hin, who mined the fields around Rawang in the hills north of Kuala Lumpur. The competing Chinese factions were drawn into the Malay civil war when Raja Mahdi, in an effort to recoup his fortunes after his defeat at Kelang, recruited the Ghee Hin as allies and attacked Kuala Lumpur. Yap Ah Loy had no choice but to throw in his lot with Kudin’s forces. The Chinese had become embroiled in a Malay civil war.

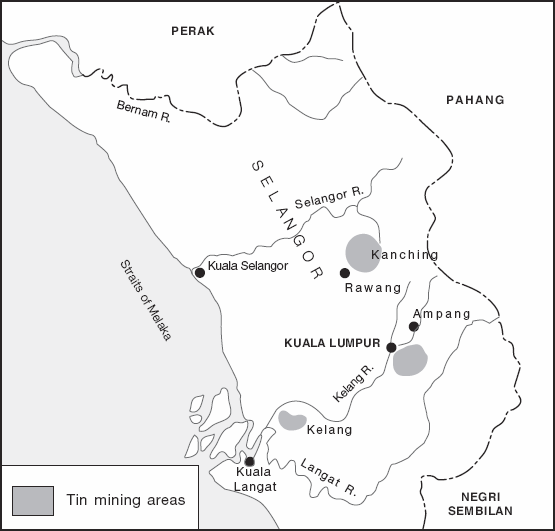

Tin mining areas in Selangor.

The conflict could not help but spiral beyond the borders of Selangor and into the Straits Settlements. Both secret societies had significant followings in Penang and Singapore. In 1872, Mahdi and the Ghee Hin captured Kuala Lumpur, but Yap Ah Loy took it back in 1873 with the help of recruits from Pahang.

British and Chinese businessmen had significant investments in Selangor. The disorder made it difficult to obtain tin at a time when demand was rising. Both sides in the war had borrowed money from people in all three Straits Settlements to conduct the war, and this added to concern about the eventual outcome. The Straits Settlements government eventually weighed in on the side of Kudin, in part because he was believed to be the legitimate authority, having been appointed by the sultan, and in part because Mahdi and some of his followers had attacked shipping in the straits.

Most importantly, the business community of Singapore felt that Kudin would maintain the stability needed to carry on trade. Colonial Secretary J.W.W. Birch, publicly voiced British support for Kudin and lent him a British warship to blockade Mahdi’s base at Kuala Selangor. Governor Sir Harry Ord encouraged Pahang to send fighters to support Kudin’s cause. In 1873, the tide turned in Kudin’s favor, most probably because of British intervention. Kudin’s victory was a point well taken by other leaders in the peninsula. Kudin had won a Malay civil war with little Malay support. A traditional Malay power structure could survive with British assistance.

Perak suffered a fate similar to that of Selangor in which Chinese turf rivalries mixed with Malay politics and caused large-scale violence and civil disorder. Perak had traditionally been a source of tin, but in the 1840s, large deposits were discovered in the Larut district, which was led by a local chieftain by the name of Long Ja’afar. There was a “tin rush,” and within two decades, over 40,000 Chinese were working in the mines. This number was greater than the entire Malay population of the state.

Long Ja’afar died in 1857 an extremely wealthy man, and his son, Ngah Ibrahim, inherited his interests in Larut. He not only received his father’s wealth but also the headaches that went with the Chinese migrant population and its secret societies. Initially, he solved the problem of Chinese rivalries by playing the two most prominent groups off against each other, the Hai San and the Ghee Hin, the same two that had clashed in Selangor. It was a game Ngah Ibrahim could not win. In 1861, violence broke out between the two groups over a gambling dispute, but the real issue was control of the mines and the opium trade. Ngah Ibrahim realized the Hai San were the stronger of the two and sided with them despite that fact that they had started the fight. As a result, the Ghee Hin were driven out of their mines. Many of them fled to Penang.

Significant numbers of miners had originally come from the Straits Settlements or claimed they had, and as a result, they were viewed as British subjects. The Ghee Hin appealed to Governor Cavenagh for compensation and the return of their mines. Cavenagh demanded that the sultan address their grievances. Sultan Ali, like many of his contemporaries in Malaya at the time, had limited control over the revenue from the state’s resources and was weak politically. Local chieftains, such as Ngah Ibrahim, were wealthier than their sultans and could buy the support needed to defy them. The British then blockaded the coast to force a settlement.

Ngah Ibrahim caved in, paid compensation and returned the mines to the Ghee Hin. In return for his acquiescence, the sultan bestowed a new title on Ngah Ibrahim – orang kaya menteri (elder minister) – and gave him control over the Larut area. For a commoner, this was heady stuff, greatly increasing his power and prestige.

Upon the death of Sultan Ali in 1871, these disputes between the Chinese factions became intertwined with Perak’s politics of succession. Raja Abdullah was the raja muda (crown prince) and the traditional heir to the throne, but under Perak’s laws of succession, this required the approval of the council of chiefs. Many of the chiefs in the interior, especially Ngah Ibrahim, felt Abdullah would be an unacceptable choice because Abdullah would bring the tin fields under royal control. Playing on similar fears, Ngah Ibrahim convinced the council of chiefs to install Bendahara Raja Ismail as the new sultan. His task was made easier by the prevalent view that Abdullah was a coward. Earlier, Abdullah’s wife had run off with the brother of Raja Mahdi of Selangor, and he had done nothing to exact revenge for this treachery. He was further disliked when he failed to attend the council of chiefs in the interior.

The state now had two claimants to the throne, Abdullah and Ismail. Abdullah turned to the Ghee Hin for support, while the Hai San, because of their ties to Ngah Ibrahim, supported Ismail in the ensuing civil war. In 1872, control of Larut changed hands a few times, and both societies brought in additional fighters from the Straits Settlements. A situation finally evolved in which the Hai San controlled the tin fields and the Ghee Hin organized a blockade of the coast, bringing tin mining activities to a virtual standstill. Merchants and civil servants in the Straits Settlements clamored for a change in British policy. The disorder in Selangor and Perak seriously disrupted commercial activity, and British investments and Chinese interests were threatened. There was a fear that the disputes in the peninsula would spill over into the Straits Settlements once again unless something was done. The British finally took action.

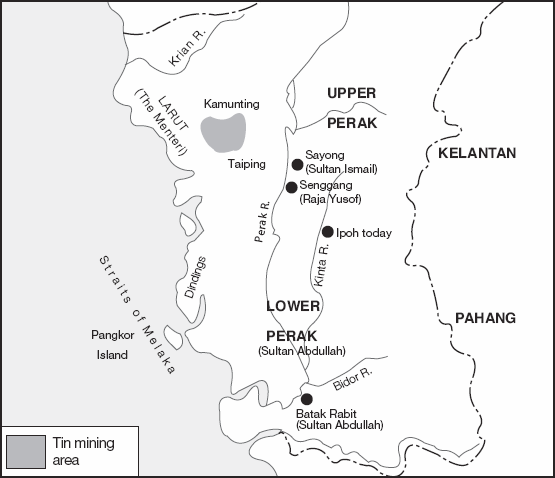

Perak during its civil war (1862–1873).

The year 1874 is usually seen as one of great significance in Malaysian history. It marks the end of the British policy of non-intervention in the governmental affairs of the Malay states. The date also marks when the British began to organize and direct the governments of the Malay sultanates.

The question of why Britain changed its official policy at this time is a matter of disagreement among historians. There are those who say that it changed because of a fear that the instability of the states would draw the intervention of some other European power and lead to a preemptive strike, so to speak.

A good case can be made, however, that this was not the primary motivation of the British. They changed course because they needed stability in the avenues of trade, especially in those that were increasingly beneficial to Great Britain. The conservative government that had recently taken power was amenable to actions that would augment opportunities for British trade and investment. Britain’s policy of free trade had produced a chronic trade deficit, and it had to compensate for it with income from trade, shipping and overseas investments.

The tremendous expansion in the amount of trade flowing through Singapore brought great benefits to Great Britain. For example, during this time two-thirds of the trade from Singapore outside the archipelago was carried on British ships. The destination of a lot of this was the United States, thus providing dollars for London by way of Singapore. What this signifies of importance is that Singapore had grown far beyond its role as a middleman in the India/China trade and had become plugged into the global economy. Historian John Galbraith recognized this in writing that Malaya had changed from a “backwater of empire to a place of great strategic importance.”

Thus the desire to maintain stable, free-flowing trade out of Singapore and Penang had to be a primary consideration for policy makers both in London and on the ground in the straits. This had been evident in Britain’s first intervention in its suppression of “piracy” and was the underlying motivation in the instructions to the new governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Andrew Clarke. He was authorized to embark on limited interference in the affairs of the Malay states. His official orders called for the “preservation of peace and security, the suppression of piracy and the development of roads, schools and police, through the appointment of a political agent or resident in each state.”

Clarke acted swiftly to solve the problems in Selangor and Perak. Within two months of his arrival in Singapore, he summoned a meeting of the warring factions to end the Perak Civil War. The meeting took place aboard a British ship off Pangkor Island in January 1874. Raja Abdullah, Ngah Ibrahim, the chiefs of lower Perak and the leaders of the two Chinese secret societies were in attendance.

This meeting produced two results. One was that the Ghee Hin and Hai San agreed to cease fighting, disarm and accept a British government commission to enforce the peace. By far the most significant agreement to come out of this meeting was the Treaty of Pangkor. This treaty signified the beginning of the creation of British Malaya. Under this treaty, Raja Abdullah was recognized as the rightful sultan, and he agreed to accept a British resident “whose advice must be asked and acted upon on all questions other than those touching Malay religion and custom.” The resident was to take charge of the collection and control of all revenue, and the chiefs were to be given allowances. Ngah Ibrahim accepted an assistant resident in Larut with the same authority as that of a resident. This was the start of “indirect rule,” whereby the British began to modernize and develop the Malay states.