9 |

IMPACT OF BRITISH RULE ON MALAYA |

The establishment of British rule in Malaya had tremendous consequences for the peninsula. In the short run, the development of modern government along a Western model created the climate for rapid economic growth. This in turn generated the revenue necessary to sustain that growth. Modern government also established conditions that were conducive to a sizable population growth, which provided the labor needed to create great wealth for British and other non-Malay investors. In the long run, British rule created a multiracial society with serious economic and political inequalities, with which the government of Malaysia grapples to this day.

The British employed a variety of rationalizations to justify their intervention and control of the area known today as Malaysia and Singapore – to secure shipping lanes; ensure free trade; end piracy; deliver the local inhabitants from corrupt and incompetent leaders; bring peace and order; end abuses, such as slavery and headhunting; preserve the traditions of societies threatened by foreign immigrants; and create the conditions necessary for economic development. All these reasons were true but were secondary to the primary British motivation for its rule of Malaya in the twentieth century – to create the necessary environment for British investors to profit from Malaya’s natural resources, especially in the FMS. And profit they did. Economically, British Malaya was one of Britain’s most successful colonial ventures.

In the nineteenth century, the focus of Malaya’s role in the world economy changed from that of an entrepôt with limited amounts of local resources for sale to that of a major producer of raw materials. Most of this initial growth, whether in tin mines in Perak or pepper plantations in Johor, was achieved with Chinese capital and labor. The close-knit nature of Chinese business organizations, be it the family or the kongsi, and the availability of inexpensive coolie labor lent themselves to the high-risk situations that existed in the peninsula, which were a result of political instability and civil disorder. An example of their success is that at the turn of the century, the Chinese controlled virtually all the tin mining areas in Malaya.

In the twentieth century, British investments poured into Malaya, and the British replaced the Chinese as the major producers of the peninsula’s export products. By 1930, British-owned concerns controlled about two-thirds of Malaya’s tin production. The value and amount of tin produced increased dramatically under the British. In the period 1898 to 1903, Malaya produced $30 million in tin; by 1924 to 1928, this had more than doubled to $78 million. At the outbreak of the Great Depression in 1929, Malaya was producing over a third of the world’s tin.

When the change from Chinese to British control of the export economy took place, the Malayan economy registered a phenomenal growth rate. In 1895, total trade of the FMS stood at $18 million; by 1925, it had risen tenfold to $182 million. The Chinese had a share in this growth, and many continued to prosper, but most of the twentieth-century growth was the result of British commercial expansion, especially in the product that truly built Malaya’s colonial economy – rubber.

In the twentieth century, a combination of visionary British officials, technological change and British policy caused a rubber bonanza in British Malaya. A form of poor quality wild rubber called gutta-percha had been exploited in Malaya for some time and was exported on a small scale. Its usefulness, however, was limited. In the 1870s, the domesticated trees, Hevea brasiliensis, which became the mainstay of Malaya’s plantations, were brought from Brazil to the Kew Gardens in London. Seeds from these trees were sent to Ceylon and Malaya, but British investors were not interested in the product. Many of them thought that the most promising plantation crop for Malaya would be coffee and planted thousands of acres of it. They also wanted quick returns on their investments, and rubber trees took six to eight years before they could be tapped for latex.

The active encouragement of two far-sighted British officials helped to change the attitude of the planters. Sir Hugh Low brought seeds from Singapore and planted them on the grounds of his home in Perak, where he was the British resident. As these trees gave up seeds, he passed them to local coffee planters, attempting to sell them on the idea of an alternative crop. His efforts were met with skepticism.

More important to the introduction of rubber as a cash crop was the head of the Botanical Gardens in Singapore, H.N. Ridley. His experiments with rubber at the gardens produced hardy trees, efficient methods of tapping the trees and ways to turn the sap or latex from the trees into rubber sheets that could be easily collected and exported. Although he is viewed as a genius today, at the turn of the century, he was seen as an eccentric who toured the country with rubber seeds, trying to convince sugar and coffee planters that rubber was the wave of the future. Among the Europeans, he was known as “Mad Ridley” or “Rubber Ridley.”

In 1839, Charles Goodyear, an American, discovered the process of vulcanization, which made rubber products sturdier and less malodorous. The popularization of bicycles using rubber tires and the invention of the automobile added greatly to the demand for rubber, especially with the invention of the inflatable tire by Charles Dunlop in 1888. When Henry Ford began to mass produce cars and make them available to the average person, rubber’s future was guaranteed. The worldwide market for natural rubber created one of the most important growth industries of the early twentieth century.

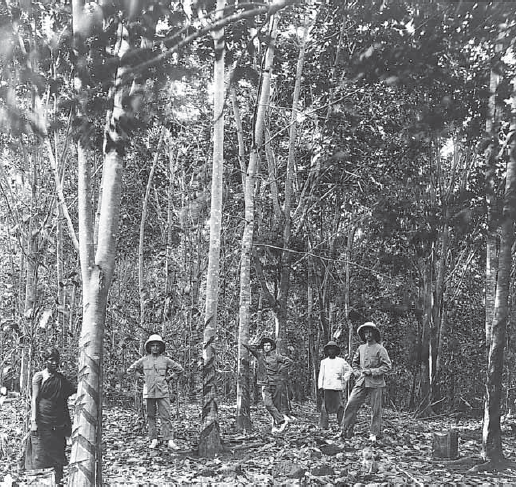

An early rubber plantation.

The British colonial administration provided further impetus for a successful rubber industry in Malaya by offering plots of 1,000 acres at inexpensive prices to investors who would plant it. The government also encouraged rubber planting by waiving land taxes and taxing the exported rubber at low rates.

All these factors caused a tremendous rubber boom in Malaya. It was first planted for commercial purposes in Melaka in 1895 by Tan Chay Yan. By 1902, there were 16,000 acres under cultivation. From there, it took off like a rocket. Within twenty years, more than two million acres of land were under rubber cultivation, constituting about half the world’s total rubber, a phenomenal expansion. In 1927, the world produced 604 million tons of rubber, out of which 344 million tons came from the British Empire, primarily Malaya.

It is important to note who took advantage of this boom and who benefited from these British policies. By 1938, over two million acres were under cultivation. Out of this, Europeans (most of whom were British) owned 1.5 million acres, Chinese 300,000, Indians 87,000 and Malays 91,000. There were 585 plantations with a size of 1,000 acres or more in British Malaya. The larger the plantation, the more efficient and cost-effective it was. Of these 585 large estates, 514 were in the hands of the British with a few owned by Americans and other Europeans. The Asian entrepreneurs had much smaller estates and lacked the sophisticated and expensive machinery to produce good quality latex.

Many Malays planted trees to supplement their income, but their trees were small and produced low-quality rubber. British officials feared that the Malays would shift away from growing necessary food crops and banned the growth of rubber on certain designated Malay-reserved land, further obstructing the entry of the Malays into this industry.

The Malay Peninsula in the twentieth century.

There are a number of other reasons why this incredible growth based on British investment took place. One important consideration was that the British administration, especially in the FMS, created the necessary conditions for investor confidence. By the early twentieth century, the British had brought the power of the central government to all but the most remote areas. This was more pronounced in the FMS but slowly evolved in the unfederated states as well. A professional police force loyal to the state meant that the lawlessness of the nineteenth century was a thing of the past. There were occasional anti-government uprisings, but British businessmen could rest easy that their ventures were safe.

British confidence was further enhanced by the legal and administrative systems that were established. To do business, investors must be convinced that the legal system in a country is transparent and consistent. In Malaya, this was true. Moreover, commercial and property laws were based on British models.

One important function of the early British administrators was the proper surveying of land in order to secure clear title to it. Not only did foreign groups developing the land benefit, but it was one of the few policies that reached down to the average Malay. Due to the mobility of the Malay agricultural community and nineteenth-century upheavals, few Malays had secure ownership of the land they tilled. The British surveys and consistent property laws gave many of them titles to their lands.

A modern administrative system along British lines was essential to providing another key prerequisite for economic development, a modern infrastructure. The building of roads and railroads and the establishment of communication systems, such as post offices and telegraphs, were necessary foundations, and the British attacked the problem of infrastructure with a vengeance. In 1896, the FMS spent nearly half their total revenue on road and railway construction and other public works. By 1900, $23 million had already been invested in railway construction, and 579 km (360 miles) of track had been laid. From 1900 to 1912, more than half the annual expenditure was spent on public works, buildings, roads, bridges and railways. Railway mileage increased to 1,632 km (1,014 miles) in 1920. By 1928, there were paved roads from Johor Bahru to the Siamese border. Bridges were built, port facilities were developed and rivers were dredged.

The pattern of this construction was indicative of British economic interests. The vast majority of investment in the transportation system was along the western coast in general and among the FMS in particular, which had the lion’s share of British investments. The first railways were from the Perak mining areas to the coast, but as industry grew and expanded to other areas of British influence, the railways were developed North-South to provide access to the ports and the tin smelting facilities in Penang and Singapore. Transportation was a key factor for the rubber industry as well, as it was able to export rubber through Singapore and Penang.

The availability of inexpensive labor was important in the economic development of the areas under British influence. The most logical source of labor would have been the indigenous Malay population. For a variety of reasons, however, they played a minor role in providing the labor to develop the rapidly growing economy. Instead, the British actively encouraged the importation of labor from China and the Indian subcontinent. The consequences of this decision were major factors that molded modern Malaysia.

By far the greatest contribution to the growth of Malaya and the Malayan economy by migrant labor and immigrants came from the Chinese. In the nineteenth century, Chinese immigration had created virtual Chinese cities in Penang and Singapore. The Chinese were vital to the development of the tin industry in Perak and Selangor and plantation agriculture in Johor, Melaka, Penang and Province Wellesley.

In the first three decades of the twentieth century, the numbers of Chinese as well as their roles in the economy expanded dramatically in the FMS and to a lesser degree in the unfederated states. Between the turn of the century and the outbreak of World War II, the Chinese population tripled from some eight hundred thousand in 1900, when they made up less than a third of the population, to over 2.5 million in 1941, when they constituted close to half of Malaya’s population. The Malays were a minority in their own land, accounting for about 41 percent of the population.

Just as significant as their growth in numbers was the incredible variety of economic roles the Chinese played that were essential to British plans for development. Many Chinese, when they first arrived, provided cheap coolie labor in tin mines, rubber estates and ports. As time went on, the Chinese began to act as middlemen and retailers. The British were interested in large-scale capital investment that could produce profits for their shareholders back home and in developing markets for their manufactured goods. This left a host of economic activities that the Malays were either unable or unwilling to undertake. Small-scale enterprises, such as trucking firms, ice factories, coastal shipping, buses, food processing, pawn shops, entertainment centers and rice milling, were taken over and eventually dominated by Chinese immigrants. They also provided skilled labor as welders, mechanics, carpenters and bricklayers, which were essential to a growing economy.

Malayan roads and railways in the 1920s.

Table 9.1: Racial Population of Malaya, 1911–1941 (includes Singapore)

Purcell, Victor, The Chinese in Malaya, Appendix III.

In the same vein, while the British wanted to sell the goods coming out of their factories at home, they had no desire to run the shops that actually sold these goods to the general population. As Malaya’s population grew and developed a taste for manufactured goods, the Chinese stepped in to dominate the retail trade. The Chinese shophouse with the family living upstairs and conducting business downstairs has become an enduring image of Malaysian life – and has fed the stereotype of the Chinese as a race of shopkeepers and businessmen.

This movement of the Chinese from migrant laborers to players in a variety of economic roles was reinforced by the fact that more and more Chinese began to view Malaya as their home and sink roots into their communities. For example, in 1911, only 8 percent of the Chinese population in the FMS was native born. By 1931, this had increased to 29 percent. This trend toward a more settled Chinese community was given a boost by the emigration of increasing numbers of women to Malaya. The Chinese were moving away from a community of migrant laborers to a community of permanent resident immigrants.

Among some of the countries that have grown and prospered in the last hundred years, a common ingredient has been the existence of a large immigrant population. Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Singapore, Hong Kong and Argentina have large numbers of people with “immigrant mentalities.” They refuse to accept what fate has dealt them and want to build new and better lives. They are adaptable and willing to accept new ideas and new ways of doing things. Beyond this, once they leave their home countries, there is no turning back. They have to make it or starve. They have cut off ties with their friends, families and villages; if they fail, there is no one to turn to for help. They are thus willing to work long hours at any job to lay the foundation for future economic success. These factors are important reasons why the United States has become the world’s leading economic superpower. They also explain why Chinese communities all over Southeast Asia prosper to this day.

Another aspect of the Chinese community worth noting is where they lived. For the most part, they were urban dwellers and lived mainly on the western coast. As Malaya’s new cities – Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, Singapore and Johor Bahru – grew, a common factor was the presence of large numbers of Chinese. At the time of independence in 1957, half the Chinese lived in the cities and towns, and about two-thirds of the populations of Malaya’s cities were Chinese. The British controlled the production and export of raw materials; the Malays, by law and custom, controlled most of the staple agricultural food production; and as the country prospered, the Chinese lived where the economic action was – in the cities and towns.

The Chinese community also provided the market for what would prove to be Malaya’s most important source of government revenue. Throughout British Malaya in the first few decades of the twentieth century, much of the money needed to build roads and railways came from the sale of opium. It made money from opium in two ways: through import duties on opium when it entered the country and through licenses sold to those who in turn sold opium to the addicts.

The importance of opium to the finances of the Straits Settlements, where as late as 1928 it still made up a third of government revenue, has already been pointed out. Opium as a source of income might have been understandable in Singapore and Penang as they were free ports and had few sources of income, but from 1900 to 1930, close to a quarter of FMS government revenue was generated by opium. The figure was 43 percent for Johor in 1913, and in 1922, it was 29 percent. Similar statistics existed for Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu.

It is clear that British authorities were perfectly happy to benefit from the opium addictions of Chinese coolies, many of whom spent 40–50 percent of their wages on it. The profits made it possible to keep taxes on tin and rubber at very low levels. It could be argued that the low taxes were necessary to encourage investment and economic growth, but the opium trade was not one of Britain’s finest moments in its stewardship of Malaya.

Indians played a key role in the modernization and development of twentieth-century British Malaya as well. While the Indian community grew in numbers in the first few decades of the twentieth century, as a percentage of the overall population, it remained quite stable. In 1901, the Indian population of the FMS was around 60,000; by 1921, it had increased to 300,000. It continued to grow but was always about 10 percent of the total population.

Like most of the early Chinese migrant laborers, the Indians planned to be in Malaya only long enough to improve their economic lot and then return home. Because they came from British India, this plan was more feasible than for the Chinese and resulted in a transient Indian population. Labor recruitment was better organized and enforced, and it was relatively easy to return home when their contracts expired.

The term “Indian” in Malaya’s population figures describes all people from the subcontinent, be they Hindus or Muslims from India or Buddhists from Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Although most Indians came as laborers, especially to work in the plantation industries, there was an economic diversity in their community. In 1931, over one half of the Indian population in the FMS lived on plantations, and Indians made up two-thirds of that labor force. However, coming from British India, they had a history of dealing with the British and access to the English language, which resulted in many Indians filling positions as clerks in the government and private industry. Because of their experience with the Indian railways, there was heavy Indian representation in both operating and building railroads. The same was true of the police force. As time went on and professions became open to Asians, Indians were represented beyond their percentage of the population in areas such as medicine and law.

As a group, the Indian community that settled in Malaya did not prosper as much as the Chinese. By the 1950s, the per capita income of the Indians was a third less than that of the Chinese. To this day, large numbers of Indians are still over-represented in low paid occupations in manual and menial labor. The “immigrant mentality” should have driven them as it did their Chinese counterparts, but a majority of the Indians did not have an immigrant experience in its classic sense. Their opportunities for social and economic mobility were hindered by the plantation system. Since they were British subjects with close ties to British India, the Malayan government took a deeper interest in the terms and conditions of their employment. They were given housing on the plantations with education for their children and access to health care, as well as food and clothing. They lived in secure and isolated societies that were vastly different from the dynamic sink-or-swim experiences of other immigrants.

This is not to say that the Indians lived in some kind of paternalistic workers’ paradise. Conditions on the plantations varied from place to place. Generally, pay was low and the amenities basic. Because of the need to maintain a pool of inexpensive rubber tappers, educational opportunities were deliberately kept at a minimum. Education on the plantations was conducted in Tamil and stopped after the primary level. Over half the Indian community had little opportunity or ability to participate in the economic boom other than as laborers. This contrasted with the lifestyle of the Indian community in Singapore and with Indians who migrated to cities in Malaya, where they had access to English-language schools and lived the immigrant experience and subsequently benefited from it.

Table 9.2: Principal Occupations of Races (1931)

Census of Population, Straits Settlements, 1931

Another problem that the British had to overcome was that Malaya was not a particularly healthy place to live. Development could not realistically proceed until some attempt was made to deal with the malaria, dysentery, cholera and smallpox that flourished. Public health problems were further complicated by the growing cities and the consequent large numbers of people living in close proximity. In 1910 alone, malaria claimed sixty lives out of every thousand people. The building of Port Swettenham (now Port Kelang) near Kuala Lumpur was almost abandoned because of the number of workers who were dying from tropical diseases. In the Straits Settlements, it was estimated that one in five indentured coolies died, in part because of low public health standards.

The most successful British efforts to improve health standards were against malaria and beriberi. In the late nineteenth century, British and Italian researchers discovered that the Anopheles mosquito was the carrier of malaria, which gave British government medical officer Malcolm Watson the key to fight the disease. His pioneering methods in draining swamps and oiling streams controlled the breeding and earned him a knighthood. A mosquito advisory board was established to coordinate the mosquito destruction. On the western coast of Malaya, the death rate from malaria was cut by over two-thirds. Watson estimated that over a hundred thousand lives were saved through government efforts.

In 1896 alone, over two thousand Chinese died from beriberi. W.L. Brandon discovered that the disease was caused by a vitamin deficiency. The Chinese preferred to eat polished rice from which all the nutrients had been scrubbed. Once their diet was adjusted, the disease was virtually eliminated.

Improved public health was most successful in the federated states because of the existence of a centralized health bureaucracy. It should be noted that this was an important consideration in the economic development of the area because of the need for a healthy work force. Significant amounts of government revenue were directed toward building hospitals, establishing sanitary boards with health inspectors, improving water supplies and setting up infant welfare centers. A further indication of the importance of this problem to the British was that the first few opportunities for Asians to enter the professions were in the area of medicine. In 1905, the King Edward VII College of Medicine was established in Singapore to train local doctors for service in British Malaya.

Health services in the unfederated states tended to lag behind those in the federated states due to lack of revenue and distrust of Western medicine. Even in the federated states, there were significant inequities between health services provided in the towns and rural areas. On the whole, however, British Malaya was probably the healthiest place to live in Southeast Asia in the first half of the twentieth century.

The growth of government and the variety of services it provided, along with the tremendous expansion of the economy, brought about the need for a modern education system. British policy on public education was a host of conflicting attitudes, contradictions and objectives that reflected the multiracial society they had created. The policy also reflected the ambiguities of the system of indirect rule. British Malaya did not have an education system as such, but rather a variety of systems operating simultaneously and based on race, language and social class.

British education policy toward the Malay community attempted to preserve Malay tradtions and culture. Two educational policies evolved: one for the Malay aristocrats in whose name the British ruled and one for the common rural Malays whose culture they were “preserving.”

To train and recruit sufficient teachers who knew and understood the Malay people would be difficult and expensive. Also, the British were faced with a generation of the Malay ruling class that had little role or purpose in the new order. To deal with these problems, they provided English education to the sons of the Malay elite and then brought them into the civil service, albeit at the lowest levels. The most successful example of this goal was the establishment of the Malay College at Kuala Kangsar in 1905. There the sons of the ruling class were brought together at the “Eton of the East.” Malays of high birth were treated to the curriculum, sports and rules of the English private schools, although they also studied Islam and Malay. Other members of the Malay ruling class were offered scholarships to English-language schools in Ipoh and Kuala Lumpur, as well as in Johor and the Straits Settlements.

The impact was twofold. The education tended to further isolate the ruling class from the common Malays, and it reinforced the position that Asian participation in government was to be dominated by the Malays.

The average rural Malays received four years of free primary education in the Malay language. The British believed that the expectations of the Malays should not be unduly raised and that they were best suited to agricultural occupations. Initially, even these basic government schools were not popular with the rural Malay communities. Traditionally, education had revolved around the study of Islam, and many parents and religious leaders were highly suspicious of the secular schools. To Muslim teachers, they were a threat to their positions in the community. To parents, they represented government intrusion into a rural value system as well as the loss of necessary labor on the farm.

Those who attended government schools had poorly educated and trained teachers, but this changed in the 1920s and 1930s. One of the contributing factors was the establishment of the Sultan Idris Training College (SITC) in 1922. The aim of the college was to train Malay-language teachers and thereby improve the quality of rural schools. It also offered an avenue for the creation of a modern Malay identity. Malays of common background were drawn from all over the peninsula, and the college quickly became a center for the study of the Malay language and a clearing house of ideas and opinions about the challenges facing the Malay people.

The graduates of SITC, along with the efforts of Richard Winstedt, the director of education, breathed new life into the Malay-language schools. The curriculum failed to provide the rural Malays with the necessary tools to compete in a modern economy, but the study of the Malay language and literature did help define more clearly what it meant to be a Malay.

The educational policy toward the Chinese reflected the government’s overall view of the scheme of things in Malaya. In its eyes, the Chinese were a transient labor force, and thus there was no need to provide education for them. Up until the 1930s, education was purely a private affair. A proliferation of schools in the Chinese language was established by clan groups, dialect groups, kongsi, wealthy Chinese and itinerant teachers. The quality of these schools differed significantly throughout British Malaya. Some in the urban areas that enjoyed generous, private funding were quite good, but most were inadequate. Large numbers of Chinese schools were run by teachers whose only qualifications were that they could read and write.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the government took a greater interest in the Chinese schools but for political rather than educational reasons. Some teachers were recent arrivals from China and had brought with them the turmoil that had engulfed China after the fall of the imperial government in 1911. There was a civil war between the noncommunist Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to decide who would replace the Ch’ing dynasty as the next ruler of China. This ideological battle came to the Chinese schools in Malaya. They were used as sources of propaganda and as vehicles to raise money for the competing factions. Both sides in the Chinese civil war were deeply nationalistic and wanted China free of foreign control. They foresaw a new and powerful China, free to establish its role in Asia. This view easily translated into Chinese chauvinism (excessive, almost blind patriotism) and anti-British agitation, which caused concern among British officials.

To counter this development, a Chinese inspectorate of schools was established in the 1920s to monitor the curriculum, and the government began giving financial aid to the schools in order to have government control over what was taught. The effectiveness of these measures was limited because there were budgetary constraints during the Great Depression, and most British did not understand or speak Chinese. Little was done to improve the quality of instruction, and the schools continued to be taught only in the Chinese language.

By stepping in to oversee Chinese education, the British were beginning to acknowledge that many of these Chinese intended to stay in Malaya permanently. They, however, still failed to realize the need for schools to promote a Malayan outlook, that is, to foster among Chinese youth a feeling that Malaya was their home. The continuation of the curriculum in the Chinese language reinforced the separateness of the races and reflected the roles the government foresaw for the different races. To many British policy makers, the Malays were to remain fishermen and farmers; the Chinese were to work for other Chinese as laborers or retail traders; and the Indians were to remain clerks, plantation workers and laborers.

The three races did intermingle in many of the English-language schools. The British view that the races should be educated in their individual native tongues was qualified by the government’s need for English-educated Malayans. The government already offered these opportunities to Malays, but as the economy grew, it began to offer them to all English-educated people. The language of commerce was English. As the population expanded and the country modernized, opportunities in the professions widened. The country needed doctors, lawyers, engineers and architects, and it was impossible and impractical for them all to be British. The road to participation in any of these areas was through the English-language schools.

The English-language schools were primarily in the urban areas, and they were established through a mixture of public and private efforts. The government established Raffles Institution in Singapore and later other schools, such as Victoria Institution in Kuala Lumpur and King Edward VII in Taiping. These schools, however, were not for everyone. The government felt that English education should be limited to small numbers of Asians so as to avoid creating a surplus of highly educated people who could not find jobs. The colonial government was also hesitant to allocate large sums of money for education. However, before criticizing government inadequacies in public education in Malaya, it must be borne in mind that government-funded education only began in Britain in the late nineteenth century.

Some of the finest schools in Malaysia and Singapore today began as mission schools. The Methodists established an extensive school system, setting up Anglo-Chinese schools and Methodist boys and girls schools. St. Francis Xavier in Penang, St. John’s in Kuala Lumpur, St. Paul’s in Negri Sembilan and St. Joseph’s in Singapore were established by the Catholic Church. The success of the mission schools helped convince the Malayan government that it had miscalculated the need for English education. It subsequently began to support expanded English education.

What the English-language schools achieved besides offering a quality education was the creation of a multiracial elite. English gave students access to government and commercial positions. It also gave them access to higher education in English in Malaya and abroad. Studying a Western curriculum, having a common language – English – and having good prospects for the future gave these elite groups more in common with one another than with their respective racial groups. In the 1930s, the breakdown of the racial composition in the FMS English schools was 49 percent Chinese, 27 percent Indian and 15 percent Malay, with 9 percent others. The leaders who led Malaya and Singapore to independence were primarily the products of these schools.

The legacy of British rule up to World War II was a booming economy that made huge profits for British investors while offering some opportunities to immigrants and the Malays. The British built a modern centralized government with specialized services in health care and education. They created the modern infrastructure needed to spark off economic growth. They established the rule of law. All these accomplishments have been extolled by British ex-civil servants, British historians and British authorities.

While the British could point to solid achievements in Malaya, there were some serious flaws in the economy and society they had created. The economic health of the country was basically tied to only two commodities – rubber and tin. Good times and bad times would be determined by the world market prices for these two products.

The reality of depending on only two commodities was brought home by the Great Depression. When the world demand for these products dropped, the economic fortunes of most of the immigrants fell with them. Tens of thousands of Chinese were forced to the fringes of the jungle, where they became subsistence farmers in order to survive. Many Indians were forced to return home to a country that could not absorb their labor. The Malays were a little better off than the immigrant races because they had little contact with the modern economy and were already subsistence farmers. This in itself was indicative of the society that had evolved in British Malaya. The poorest faced the least dislocation because they had little stake in the new economy. Serious inequalities of wealth had been created both among and within the races.