13 |

MALAYA AFTER THE WAR |

An observer of Malaya in the 1930s remarked that it was “a country without politics.” For the most part, this was true. The immigrant races were more interested in the politics of their home countries, if at all, and the average rural Malay had little interest in the affairs of state. The Malay aristocracy was secure in its role as the symbol of Malay rule. And the British were happy making money.

Unlike India, Indonesia and Vietnam, Malaya did not have a significant nationalist or independence movement. The Japanese occupation changed this. When the British returned in 1945, the peninsula had become intensely political. The changing population, the war and British plans for the future of Malaya worked together to create interest in the political future of all who called Malaya home

The war, the Japanese occupation and immigration altered some of the fundamental premises of Malay political life. One of these was the idea that immigrant races were to be excluded from politics and government. Prior to the war, British policy had supported the sovereignty of the Malay sultans and followed a “Malay only” policy for employment in the civil service. The immigrant races were considered transients who were not to participate in the workings of government.

A growing number of native-born Chinese and Indians challenged this belief, especially after the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) had fought for Malaya by resisting the Japanese. The vast majority of those who fought the Japanese were Chinese who were not only interested in defeating the occupiers, but in creating a post-war communist Malaya. These war-time activities had politicized both the Chinese and the Malays. For the first time, Chinese political leaders in Malaya were talking about their plans for their country. This was a direct threat to the Malays’ view of Malaya as their country and their land, as well as their government.

The belief that the British were the protectors of Tanah Melayu (land of the Malays) was destroyed by the war. The British could not be trusted to preserve the states as Malay states. The British had lost Malaya to the Japanese, and when they returned, their initial plans for the political future of Malaya were viewed as detrimental to Malay interests.

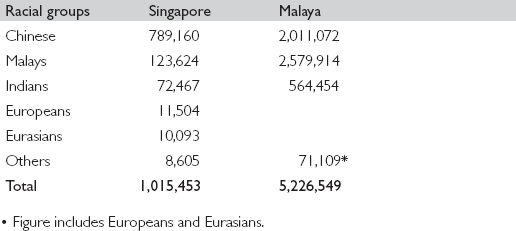

Table 13.1: Population of Malaya and Singapore, 1950

During the war, the colonial office in London had formulated a blueprint for post-war Malaya. Although it accepted little input from the Malays, it recognized Malaya’s fundamental political dilemma – balancing the desires of native-born immigrant races for citizenship and political participation with the Malay view that control of the government should remain in Malay hands. This problem was further accentuated by the fact that the Malays had become a minority, albeit the largest, in British Malaya. British planners realized that the days of the empire were numbered. Malaya, like the rest of its colonies, was inevitably moving toward self-rule. At the same time, the British had huge investments in Malaya and wanted to protect their economic interests. This required a friendly, stable government that would allow British commercial ventures to continue to prosper. To these ends, they proposed the creation of the Malayan Union.

The Malayan Union represented a fundamental change in the nature and organization of the way Malaya was governed. Under the union plan, the FMS, unfederated states, Penang and Melaka would be joined together to form a unitary state ruled from Kuala Lumpur. The individual sultans were to be persuaded to cede their sovereignty to governors who would rule in the name of the British crown. Legislative and executive councils would be responsible for law-making on a national basis. The sultans would have power over only religion and Malay custom, and the states would not be governed in their names.

Citizenship would be bestowed on all who were born in Malaya or had lived there for ten of the previous fifteen years. All others in Malaya could obtain citizenship through a future residency requirement of five years. There were to be equal rights for all citizens in the new state. Government administrative posts would be open to the immigrant races. After a transitional period, this new arrangement would lead to a democratic, self-governing, independent Malaya.

Singapore was to be spun off as a separate colony because its large Chinese population was seen as a political threat to the Malays and also because of its strategic and military importance to Britain.

The British plan was revolutionary. It was meant to be a way to offer the immigrants a future, unite the country and provide the means to help the less developed parts of the country. What it turned out to be was a total disaster, especially in the eyes of the Malays.

Initial British moves to institute the union had met with success. They had quietly convinced the sultans to acquiesce to the Malayan Union. The sultans went along with British plans because British officials implied that those who did not could be considered collaborators with the Japanese for having continued to rule during the occupation. Another reason was that the British fast-talked the sultans and played down the ramifications to the Malay community. Whatever the reasons, the sultans failed as a first line of defense for Malay political rights.

To most Malays, the Malayan Union was a sellout. The assumption had always been that the immigrants could participate in the economic life of the area, but political life was to be dominated by the Malays. Even though indirect rule had been a façade, the sultans had remained powerful symbols of Malay sovereignty, and colonial office planners had misjudged their importance in the eyes of the Malays.

The special position and privileges of the Malays, backed by British guarantees, did not exist under the Malayan Union. In a democratic unitary state with liberal citizenship laws, the immigrant races would eventually control the political as well as economic power of the country. In five of the wealthiest states, the Malays were already in the minority, and the symbols of Malay power, the sultans, were the only political links they had with their own country.

Attempts to mobilize the Malay community in the 1930s and 1940s and the creation of a Malay political and national consciousness revolved around three approaches. One response was religious in nature. In the early twentieth century, there was greater contact between the Malay community and the Middle East. In part, this came about because increased prosperity and inexpensive travel had made it possible for greater numbers of pilgrims to visit Mecca and participate in the Hajj. It also took place because rising numbers of Malays were going to the Middle East for religious training and higher education. Many of these students returned fired up with the spirit of Islamic reform, which was popular in the Middle East at that time. They felt the answers to the challenges of a modernizing world could be found in a purer form of Islam. They believed that Islam in Malaya had been corrupted by adat law and local custom, making it unable to stand up to the cultural and economic threats of the West and the immigrants. With allegiance to the true teachings of Islam, the Malay community could preserve its position and values.

A second group of Malay leaders that arose at this time came from the Malay-educated intelligentsia, made up mainly of rural Malay-language school teachers, minor government officials and journalists. Their awareness of the problems facing the Malay community had been heightened by access to schools, such as the Sultan Idris Training College, where they had been exposed to the ideas and literature of the larger Malay-speaking world, including the anti-colonial nationalism coming out of Indonesia at this time.

One of the first Malay political organizations came from this group – the KMM, or Young Malay Union, led by Ibrahim Yaacob. Pan Malayanism as a bulwark against the immigrant races had great appeal for this group. During the war, the Japanese had encouraged the KMM to assert itself and develop its contacts with Indonesian nationalist groups. They saw race and language spanning across Sumatra and other Malay-language areas to create a greater Malay nation strong enough to stand up to the challenges of the immigrants and the West.

The third and most successful of the groups competing for leadership of the Malay community came from the traditional ruling elite. British rule had been good to the Malay aristocracy. Their thrones and positions had been stabilized and guaranteed by British intervention in the civil disorder of the nineteenth century. Access to English education at schools, such as the Malay College and Victoria Institution, had led to positions in the government. Many had continued their education in Britain and as a result moved easily in British political and commercial circles. The British ruled Malaya in the name of these elite families. Malaysia’s first prime ministers, Tunku Abdul Rahman, Tun Abdul Razak and Dato Hussein Onn, were all from this group.

A democratic Malaya with equal political rights for the immigrant races was not only a threat to Malay political dominance but was also a threat to the traditional elite. What would be their position in a democratic country with a majority population of immigrants? In their eyes, the only answer to Malaya’s future was some kind of accommodation between the political desires of the immigrants and the Malays’ right to rule. These aristocratic leaders believed strongly in the special position of the Malays but realized that the immigrant races were essential for the economic future of Malaya and saw negotiation and compromise with them as the path to follow in creating a post-British political arrangement.

The leadership of the post-war Malay community fell to the traditional elite quite easily. The religious option appealed to some, especially those in the former unfederated states, but it had many opponents because these reformers were a threat to the existing religious establishment. During British rule, the sultans had retained control over Islamic affairs and had established a strong link between the palace and the mosque. Throughout the states, the religious bureaucracies were firm supporters of the status quo. Malayan Islam accommodated Malayan beliefs, laws and customs. Thus many members of the religious establishment were vocal opponents of the reforms offered by such groups as the Pan Malayan Islamic Party, known today as the Parti Islam Se-Melayu/Malaysia (PAS).

Pan Malayanism also had limited popular support. While it appealed to Malay-educated Malays, for the ordinary Malays, grand schemes of unity in the archipelago fell on deaf ears. The world of the rural Malays was quite small and did not reach much beyond the villages. Few Malays at this time had any concept of Malaya, let alone countries beyond its borders. In addition, the concept of Pan Malayan unity required a reevaluation of the roles of the traditional rulers and was couched in criticism of the traditional aristocracy.

That the Malay community rejected the ideas of the reformers and embraced the leadership of the traditional elite was an impact of British rule. The British had preserved the traditional link between the Malay aristocracy and the Malay peasantry. The British had maintained not only the concept of Malay rule but rule by the royal families with whom they had made the initial nineteenth-century arrangements. The royal courts’ continued responsibility for Islam and Malay custom had perpetuated the connection between the court and the kampung. The traditional concept of daulat still existed in the minds of most Malays and reinforced the view that the elite of the Malay states were the rightful leaders.

The Malay reaction to the Malayan Union was widespread and vocal. It was the first time that large numbers of Malays throughout the peninsula made common cause with one another. To lead the battle against the Malayan Union and its threat to the Malays’ position, the first major Malay political party was organized in 1946 – the United Malay National Organization (UMNO). Led by Dato Onn bin Jaafar, chief minister of Johor, UMNO organized large public demonstrations against the union and coordinated a policy of noncooperation. Malays refused to sit on any of the committees or councils that were set up under the union. The sultans refused to attend state functions and boycotted consultations and meetings with the British. Without the support or participation of the Malay political leaders, the Malayan Union was dead.

The ability of the Malay political leadership through UMNO to mobilize Malay public opinion caught the British by surprise. A people who only a decade earlier had seemed docile and apathetic were suddenly making their views known through mass demonstrations. The strength and emotion of the Malay reaction convinced the British that they had miscalculated. The British sat down with the Malay political leadership to come up with an alternative to the Malayan Union.

Throughout 1946 and 1947, British officials and representatives of the Malay rulers and UMNO hammered out a new arrangement, which resulted in the creation of the Federation of Malaya in 1948. The federation was to be an interim arrangement whereby the British would rule during a period in which greater local participation would take place in government, and the final constitution and structure of an independent Malaya would be decided.

Instead of a British governor, there would be a British high commissioner to the states of Malaya who would act as the head of the central government. The sovereignty of the states and the positions of the sultans would be maintained as per pre-war arrangements. Governmental powers were to be divided between the states and the federal government. For example, land laws and policies would be retained at the state level.

The special position of the Malays was guaranteed, and the sultans and high commissioner were the guarantors. Citizenship laws for immigrants were to be stricter than those of the union proposal and would be finalized before independence. Legislative councils for the states and the federation were established, but the majority of Malayan participation in those councils was to be Malay. What the agreement meant was that in the period of time that Malaya moved toward independence, the Malays would control the levers of government.

Singapore was still to be spun off as a separate colony.

The post-war Malay political goals and leadership were formulated with a large degree of unity, but the battle to determine the agenda and leadership of the Chinese community was slow and bloody. The Chinese were a diverse community whose political interests, if they had them, had revolved around the power struggle in China. There was no “traditional” leadership in their community, and when the war was over, the direction of the community was up for grabs.

At the end of World War II, the Chinese in Malaya were the wealthiest of the three races. Their superior average income and control of the retail trade, however, disguised sections of their community that had serious economic grievances and were threatened by the new order. Over 500,000 Chinese, about a quarter of the Chinese population, were squatters who had fled the towns and cities as a result of hard times caused by the Great Depression and the Japanese occupation. Living on the fringes of the jungle, they had no title to their lands and were isolated from government influence and services. If educated at all, it was poorly and in Chinese. For the most part, they survived off the proceeds of small rubber and vegetable holdings. Very few of these Chinese were native born, and under the proposed new citizenship laws it would be a long time before they had any political power. As the British and Malays negotiated the political future of the country, their needs and interests were largely ignored.

Most urban Chinese were educated in Chinese and made a living from relatively low paid jobs as factory workers, laborers or hawkers. Their concerns about education, housing and working conditions would no doubt be low on the list of a Malay government with a rural Malay political base. A fundamental priority of any elected Malay government had to be the economic improvement of the Malays. Any attempt to move Malays into the modern economy would appear to have a negative impact on the working class Chinese because their manual and semi-skilled jobs were the ones that would initially draw Malay competition.

For over half the Chinese community, immigration to Malaya had not resulted in great fortunes but in low incomes and hard labor. Chinaborn or the children of China-born, few had citizenship or any kind of legal or political standing, and yet, they planned to stay. The leadership of the Chinese community was dependent on these two groups, the squatters and the workers, most of whom were the “new immigrants,” families formed when large numbers of Chinese women came to Malaya in the 1930s.

At the end of the war, there was a significant shift in the leadership of the Chinese community. Prior to the war, the dominant political group had been the nationalist KMT due to its association with the ruling party of China and support from Chinese business interests backed by secret societies. But by 1945, the communists had significantly increased their stature and position among the Chinese in British Malaya. It is estimated that there were 37,000 communists, many of whom had been part of the active resistance movement during the war.

When the MPAJA emerged from the jungle after the war, they were viewed as heroes by many in the Chinese community. They participated in the victory parades and were given medals and cash awards by the British for their anti-Japanese efforts.

The communists were the best-organized political group in the Chinese community. In the first few years after the war, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) openly joined the political process, establishing branches in most of the major towns and concentrating on labor activities. The new Labor Party government in Britain was sympathetic to the activities of labor unions, and the communists took advantage of this. Organizing the Pan Malayan General Labor Union in 1946, their plan was to cause serious disruption to the economy through strikes and labor agitation and then ride the tide of discontent to power and then to the establishment of an independent, communist Malaya.

Malayan troops on jungle patrol during the Emergency.

Chinese schools provided fertile ground for recruitment and agitation by the communists. The abandonment of the Malayan Union plan had convinced many young Chinese that the Malay leadership planned to relegate the Chinese to permanent second class status. Their future seemed bleak, and the communists offered hope.

There is no doubt that the post-war recovery was slowed by MCP activities, but by 1947, it was apparent that its tactics were not generating the mass support it needed to take power. Many workers had become disgruntled by the political nature of the labor movement. In 1947, a general strike was called, as well as hundreds of other strikes. The strike pay was insufficient, and many protesters were facing economic hardship with few concrete results. Apart from this, the party was split between its leader, Lai Teck, who wanted to continue using open and legal means to gain power, and much of the rank and file, who felt this strategy was futile.

Lai Teck was facing serious problems of credibility. There were rumors that he was an agent for the British and had also worked for the Japanese during the war. The basis for these rumors was the charmed life he seemed to lead. He had appeared in Singapore in 1934, having escaped a crackdown on communists in Hong Kong and Shanghai. Some believed it was at this time that he was recruited by British Intelligence in return for his freedom. During the war, Lai Teck lived openly in Singapore and escaped two Japanese raids on meetings of the MCP leadership, fueling the suspicion that he was in league with the Japanese. After the war, his commitment to open constitutional means in the face of large-scale opposition from his comrades fed the belief that he was in cahoots with the British.

In 1947, a meeting of the central committee was called to confront Lai Teck and determine the course of the movement. Lai Teck failed to show up and disappeared, along with funds belonging to the party. Twenty-six-year-old Chin Peng assumed leadership, and it was decided that the MCP would undertake a “war of national liberation” against the government of Malaya.

What ensued was the Emergency, a twelve-year guerilla war between communist insurgents and the Malayan government backed by British Commonwealth troops. The conflict drew its name from the fact that the civil government had declared a state of emergency in order to assume extraordinary powers to fight the communists. Perhaps more importantly, by calling it the Emergency and not a war, it was possible for businessmen to collect for damage to property from insurance companies. The fight against the MCP was directed by civilian authorities with the support of the military and thus was a “police action.” To the thousands of British, Australian, New Zealand, Fijian and African troops stationed in Malaya, these semantics meant nothing. They fought and died to prevent the communists from taking over Malaya.

Once the decision to fight was made, the communists went back into the jungle and dug up the arms they had hidden at the end of the war with this eventuality in mind. An irony is that many of their weapons had been supplied by the British. The communists proclaimed that their goals were to end British rule and create a democratic, socialist Malaya. Calling themselves the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA), they were 6,000 to 8,000 strong, many of them veterans of the fight against the Japanese.

The MRLA had a natural base among the Chinese squatter community and was able to reestablish its World War II support system. The Min Yuen (Organization of the Masses), previously called the Anti-Japanese Union, numbered in the tens of thousands and provided money, food and recruits for the MRLA.

The first few years of the Emergency were bleak as MRLA activities devastated the economy and administration. One of its primary agendas was to destroy the British export economy. Much of its activity was directed at the large rubber plantations and tin mines. European estate managers and their families were attacked frequently, and their homes became armed camps. About one in ten British managers was killed, about 10 percent of the rubber trees in Malaya were destroyed and many tin dredges were blown up. In the first years of the war, the MRLA’s success stretched the British forces to their limits just trying to protect these areas from attack, let alone going on any kind of counteroffensive.

The other agendas were to undermine government credibility and eliminate opposition to communist leadership in the Chinese community. By 1950, over a hundred British and Malayan civilians were being killed every month. The MRLA hoped that the loss of leadership would create geographical vacuums into which it could step and declare that parts of the country had been “liberated.” The high point of communist activity took place in early 1951 when a unit of the MRLA ambushed and killed British High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney on the road to Fraser’s Hill, which was about 100 km (62 miles) from Kuala Lumpur. If the highest British official in Malaya was not safe from attack, who was?

Although the assassination of Gurney was a serious psychological blow to the country, by 1951, the British had discovered the right formula of actions that would eventually result in victory. The British realized the battle was political as well as military, and both had to be won in order to defeat the MRLA.

On the military side, Britain was a major world power with modern air and ground capabilities and was able to commit military resources that seriously outnumbered those of the guerrillas. In order to free the military to fight and not merely defend, the police force was expanded from about nine thousand in 1948 to some sixty thousand in 1952. The great majority of the officers came from the Malay community, which had little sympathy for the MRLA cause. Most Malays saw the MRLA activities as Chinese attempts to gain power and were thus highly motivated in their defense of the government. Also atheistic communism had little appeal for Muslim Malays.

Politically, the key strategy was to separate the MRLA from its main base of support, the Min Yuen. The main vehicle to this end was called the “Briggs Plan,” named after the head of military operations in 1949, General Sir Harold Briggs. The idea was to relocate the half million Chinese squatters into “new villages” far from the jungles that sheltered the MRLA. The plan had two goals – to protect them from the MRLA, which would dry up the supply routes and sources of recruits for the insurgents, and to win Chinese support by providing housing, schools and clinics. For the first time, the squatters had running water, electricity, sewage and other modern utilities. Thus the government was cutting off MRLA support and at the same time, winning the loyalty of the people the communists needed to continue their struggle.

After increasing the number of security forces and cutting off most support for the guerrillas, the military moved into the jungle to attack their main camps and communication lines. Long-range jungle patrols supplied by air drove the MRLA deeper and deeper into the jungle, effectively taking away its offensive capacity, and by 1954, it was no longer a serious military threat. Britain’s elite Special Air Services (SAS) made its initial reputation during the Emergency. Small SAS groups spent weeks in the jungle beating the MRLA at its own game and on its own turf, taking away the advantage that irregular guerilla forces usually have against conventional armies.

A key ingredient in British success was the police intelligence arm, known as the Special Branch. Well-trained and highly professional, the men of the Special Branch were responsible for intelligence gathering and covert anti-communist operations. All major operations against the communists had to be cleared through the Special Branch. Much of its success was attributed to its large number of Chinese members. The Malayan police and army were dominated by the Malays, while the guerillas were mainly Chinese. Without the Special Branch, the government would have had few eyes or ears in the Chinese community. The ability to identify the enemies and their plans contributed greatly to winning the war. It is said by some that many Chinese fortunes were made in the Special Branch, which literally bought off many of the communists by offering substantial rewards to members who deserted the communist cause, acted as double agents or provided information. The reward for the capture of one communist was the equivalent to ten years of wages for the average Chinese worker. The reward rose with the rank of the person captured and the amount of military equipment seized. A platoon commander of some ten fully armed men who sold out to the British could retire from the cause a wealthy man.

The fact that the Emergency was directed by the police and civilians had important ramifications for post-independence Malaya and Singapore. Police primacy reduced the role of the army and established the principle that the military was subservient to civilian authority. In Southeast Asia today, it is only in Malaysia and Singapore that the army has never played a significant political role. This is a legacy of the anti-communist effort.

With the Briggs Plan, increased military capabilities and an excellent intelligence network, the British had the right ingredients to win the war, but it took inspired leadership to make the plan effective. In 1952, General Sir Gerald Templer was given control of the civil administration as high commissioner and director of military operations. By combining civil and military commands, Templer was able to follow a carrot-and-stick strategy. The country was color coded black, grey and white, depending on the amount of MRLA activity and support. If the area was black, which meant a high degree of communist activity, the authorities made life miserable for the residents through curfews, food rationing and searches. On the other hand, areas that contributed information toward capturing guerrillas and cooperated with the authorities were classified as white and received overwhelming government support.

Templer made the choices real by a hands-on approach, constantly traveling across the country to show the flag and demonstrate to the people that the government took a sincere interest in their problems and future. This approach rubbed off on his key advisors who also spent much time outside Kuala Lumpur and as a result had a real feel for what was happening in the countryside. In his two-year term as high commissioner, the number of active MRLA fighters was reduced dramatically, and the majority of the country lived in peace. The people of independent Malaysia named a national park after Templer in recognition of his contributions.

The war in Malaya heightened racial tensions at a time when leaders were searching for a way to create a united multiracial society. The fact that the MRLA was predominantly Chinese and the police and army predominantly Malay gave the conflict significant racial overtones. Many Malays also resented the amount of money spent to resettle the Chinese in the new villages. It seemed ridiculous to spend millions to improve the lives of immigrants who were potential enemies, especially when many Malays lived without the services that had been lavished on the squatters. On the whole, the conflict increased Malay mistrust of the loyalties and objectives of the Chinese.

The Emergency brought a large portion of the Chinese community into the mainstream of political and economic life. A fifth of the Chinese community was resettled, making it even more urban than it had been previously. More than this, the Chinese community was forced to become part of the political community. The Chinese could no longer exist apart from government control and influence. It was their country, their government and their future too.

Defeating the militant communists was important, but for the country to move forward, the Chinese community needed a political alternative to the MCP. There were large numbers of Chinese who opposed the MCP, but they were slow in coming together to meet the communist threat. In 1948, when the federation was being negotiated with the Malay leadership, the lack of Chinese input was as much due to Chinese diversity and apathy as it was to Malay indifference to Chinese needs.

The one group that did make its voice known was the Straits Chinese. This group was quite vocal in its support for the rights of Malayan-born immigrants. Because Malaya was also their country, the Straits Chinese saw no reason why they should not have rights similar to those of the Malays. Their problem was that they were an English-speaking elite of the Chinese community (about 10 to 15 percent of this group) and did not represent the more recent Chinese immigrants.

There were two other main sources of noncommunist support in the Chinese community: the thousands of Chinese who ran family retail businesses and the Chinese-speaking merchants. Neither group had much interest in politics nor had any kind of political organization to make their opinions known. Among the three groups, there was a growing awareness of the need for a Chinese mass organization that could be a mouthpiece for their needs.

The Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) was founded in 1949 as a noncommunist Chinese political voice. Although its leadership was dominated by the Straits Chinese, it represented diverse noncommunist interests. Its first president was Sir Tan Cheng Lock, and it came into existence at the urging of the British who desperately wanted a moderate Chinese voice in politics. The MCA represented a group of Chinese who wanted a political role for the Chinese community as it moved toward independence. Many of its early activities were directed at the new villages, running social welfare programs and helping the people who had been resettled. This was an important role for the MCA because these people not only needed better lives but also to be brought into the noncommunist political life of the country.

By the early 1950s, the MCA was a full-fledged political party whose views were sought and respected. It represented a significant portion of Chinese opinion, and the lack of any other Chinese voice of importance other than the communists gave it the lead role in representing the Chinese community.

In post-war Malaya, the Indian community was in a weak political position. As the British began to hand back power to the inhabitants of the peninsula, the Indians did not have much influence on the nature and structure of politics. The Indians made up only 7 or 8 percent of the population, but the Indian community’s inability to play an important political role after the war was also the result of its being divided. About half were Tamil-educated plantation workers who were isolated from the urban half of the community. Some urban Indians were part of an English-speaking, white-collar elite while others provided much of the manual labor in the cities. The three groups did not have much contact with one another, and unlike the Chinese, they did not have the clan, dialect and trade associations to bring them together. Only a little more than half were born in Malaya, and thus many did not see the country as their home.

Like the Chinese prior to World War II, the Indian community had little interest in the politics of Malaya. Their political attention had been directed toward the anti-British struggle in India. Evidence of this can be seen in the success of Bose in recruiting Indians from Malaya to join the INA during the war. They had enlisted with the idea that they were going to participate in the liberation of India from British rule.

While the Chinese could use their economic power to obtain concessions for their community, most Indians did not have this leverage. The heavy concentration of Chinese in the cities, where they made up the majority of the population in 23 of the country’s 25 largest towns and cities, meant that in a democratic system there would be a Chinese urban majority. The Indians were a dispersed and divided community, and nowhere in the peninsula did they make up a majority of the voters.

The first major Indian political group was the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC), which was formed under the leadership of John Thivy in 1946. In the beginning, the MIC did not represent a significant portion of Indian public opinion. Its non-Tamil, English-educated leadership adopted a non-communal approach to politics and joined together with other radical groups in opposition to the federation proposal. Its ties to the Indian labor class were poor at best, and this proved to be its greatest weakness. Thus the Indian community had few political leaders who could articulate its needs and aspirations. They would have to ride the coattails of the Chinese in defending the rights of the immigrant races.

When Sir Gerald Templer arrived in Malaya in 1952, he made it clear that Malaya was being prepared for independence. That was the British commitment to the Malayan people, but the politicians knew that independence would come only when a system was devised that provided for multiracial political participation and cooperation. Given the needs and expectations of the different races, it was going to be difficult to reconcile democracy with interracial cooperation.

The Malay community was highly suspicious of any move that increased immigrant political rights. The high number of Chinese residents, the specter of the recent Malayan Union proposal and the Emergency had made it unlikely that any Malay leader would accept one man/one vote democracy along with liberal citizenship laws. Malay political prominence and Malay economic improvement were the bedrocks of the Malay leaders’ agenda and were non-negotiable.

On the other hand, the immigrant communities had legitimate concerns about their future in the country. Some of the immigrants had lived in Malaya for generations – far longer, for example, than some of the Sumatran immigrants, who were classified as Malay and were therefore part of the group with special rights. These non-Malays had helped build the economy and the country and saw no reason why they should settle for second class citizenship.

Hundreds of thousands of more recent immigrants had no citizenship. The experiences of the war and the Emergency had tied them closer to their newly adopted home. Living standards and conditions were improving and larger numbers were seeing better lives than could be achieved in China or India. They wanted guarantees that their property and economic future would be secure from a Malay government intent on raising the Malay economic position.

Many issues had racially charged overtones. Take, for example, the questions of language and education. Many Malays saw them as vehicles for national unity. They believed that the immigrant races should accept Malay as the national language, that is, learn and use the language of their adopted country. To this end, a national education curriculum had to be implemented so all the races learned in the same language.

The idea was reasonable. Chinese moving into the United States accepted that they had to learn English. But to the Chinese in Malaya, Malay as the national language threatened their cultural heritage. Perhaps if this demand had been placed on them when they first arrived, they would not have objected. British policies of separate school systems, racial economic roles and indirect rule had maintained those separate identities. The Chinese and Indians had been able to preserve much of their language, traditions and culture, and these were threatened by the Malay proposals.

The different communities had to find some common ground. In their dealings with the Malays and UMNO, the British had made it clear that they would not hand over rule to a solely Malay government because it would result in social disorder and instability. It had to be a Malayan government.

The beginnings of cooperation and dialogue between UMNO and the MCA came about in part because of a split in UMNO’s leadership. Dato Onn bin Jaafar, the founding president, felt that the organization should be a party for all Malayans. His proposals to admit non-Malays did not go down well with the rest of the organization, and as a consequence, he left the party to form a multiracial party known as the Independence of Malaya Party (IMP). Dato Onn was replaced as leader of UMNO by Tunku Abdul Rahman, a British-educated lawyer who was the brother of the sultan of Kedah.

In the early 1950s, the first steps toward democratic self-rule were elections for town and municipal councils. In Selangor, fearing the multiracial IMP in a state with large numbers of non-Malays, UMNO entered into a pact with the MCA to win the elections. The strategy proved successful as the two swept the elections. It was the start of what would become a more formal relationship. With the inclusion of the MIC in 1954, the Alliance Party was created under the leadership of Tunku Abdul Rahman. While each of the three parties maintained its separate identity and structure, they came together with a common party platform and candidates at election time.

By this time, the MIC had virtually reinvented itself. With the advent of representative democracy, the sheer numbers of Tamils in the Indian community forced the MIC to change its leadership and outlook. Tamils took over the key positions in the party, and the MIC began to vocalize the needs of the ordinary Indian worker. The party dropped its non-communal outlook and was able to find some political voice in the community as part of the Alliance.

The creation and success of the Alliance, a party that represented the three major racial groups, were received by the British with relief, and they agreed to speed up measures toward self-rule. In 1955, elections were called for the federal legislative council, in which for the first time a majority of the members were democratically elected by the people of Malaya. The Alliance won 80 percent of the vote, 51 of the 52 seats and as a result the Tunku (as he was known to most Malayans) became the first chief minister of Malaya.

The election set the tone for political parties in the peninsula. Dato Onn’s multiracial party was annihilated and, historically, political parties have found success only by appealing to single racial communities. The British legacy of the separation of the races had found its way into the electoral process.

The popularity of the Alliance, coupled with the winding down of the communist threat, convinced the British that Malaya was ready for complete independence. But before merdeka (independence) could occur, there was hard bargaining that had to take place among the leaders of the races as to the nature of the new country’s constitution. The elections of 1955 were evidence of the need for adjustment. Under the citizenship laws in place at the time of the election, only half of the adult Chinese and Indian populations had been eligible to vote.

Thorny issues of citizenship, language, Malay rights and representation all revolved around issues of race, and it is to the credit of the leaders of the Alliance that they were able, at least in the short run, to find sufficient compromise and accommodation to move forward. A British Commonwealth commission was set up to write a new constitution for independent Malaya, but for the most part, it relied on the recommendations that came from negotiations between UMNO and the MCA.

That the two parties were able to find common ground spoke volumes about the shared outlook and temperament of the elite who led these parties. While people such as the Tunku and Tan Cheng Lock fought hard for the interests of their communities, they probably had more in common with each other than they did with their own racial constituents. Under British rule, the different communities had developed separately with little interaction among the races. Differences of race, religion, language and custom, as well as economic and geographic distinctions, had been serious barriers to cooperation. This was generally not the case for the elite. Many of the MCA and UMNO leaders had gone to school together in Malaya and Great Britain. They were more Westernized than most of their compatriots and had respect for many British institutions, such as parliamentary democracy, rule of law, a free enterprise economy and basic human rights. By nature, they also had a Malayan outlook. Many of the Malay leaders had been or were civil servants and knew the benefits of central government services in promoting development. Many of the Chinese were businessmen who were aware of the potential and benefits of a national market. They all agreed that they had to create a structure that would develop a Malayan identity. This, however, would be easier said than done.

The task of the leaders of the Alliance Party was to reconcile the different demands of the races. By 1956, UMNO and the MCA had come to agreement on a number of formal and informal measures. This made it possible for the constitution to be written. The “deal” that was struck represented compromises on the part of both the Malay and immigrant leaders.

Any progress toward a democratic multiracial, independent Malaya could only be achieved by the recognition of the “special position” of the Malays, for whom this recognition was not open for debate. What did this special position mean? In general, it meant that the constitution should recognize that Malays were the indigenous people of Malaya and that government and society had a responsibility to protect their political power and improve their economic standing. They were called Bumiputera, which means “son of the soil” and includes the Orang Asli, the Malays and the indigenous people of Borneo.

This special position was accepted by the Chinese leaders and was reflected both formally in the constitution and in informal agreements between UMNO, the MCA and the MIC. The country was to be a constitutional monarchy with its king elected from the nine sultans, meaning that the head of state would always be a Malay. The king was given the responsibility of safeguarding the special position of the Malays. The monarchy created was unlike any in the world. The king of Malaya, later Malaysia, was to serve for a term of five years. When his term was up, the sultans would select another of their peers to serve the next term. There was also a second in command to reign when the king was unavailable, a vice-king so to speak. The custom was and still is that the states take turns to provide the country’s monarch.

Second, the state religion would be Islam. Other religions could be practiced but were barred from converting Malays who are Muslim by birth. Thus Islam would be maintained with government sanction as a unifying force for Malays.

Third, Malay would be the official and national language. English was accepted as an official language of the government and the courts for a transitional period of ten years, but after this period, the business of government was to be conducted in Malay.

Fourth, the formal recognition of the special position of the Malays was written into the constitution. This special position translated into reality in a number of ways. Large areas of land that had been reserved for the Malays under the British were maintained. There were quotas for admission into the civil service that guaranteed Malay dominance of the bureaucracy. In 1952, an agreement had been reached to allow non-Malays into public service but at a ratio of four Malays to every one non-Malay, and this was continued. There were also quotas on the issuing of licenses for the operation of certain businesses and services, such as taxi licenses, fishing boat permits and timber concessions. Malays were also to receive preference in government contracts and educational opportunities, including scholarships and priority in entering tertiary institutions.

Informally, UMNO and the immigrant parties agreed that electoral boundaries would be drawn and Alliance Party candidates selected in such a way that a Malay majority in parliament would always be guaranteed, and thus the prime minister would also be a Malay. Evidence of this is still seen decades later. For example, in the 1982 election, the Petaling constituency in Selangor, which was urban and had a Chinese majority, had a total voting roll of 114,704, while Kuala Krai, which was Malay and rural, contained 24,445 voters, yet each district had one member of parliament. In the 1986 and 1995 elections, 70 percent of the seats in parliament represented Malay majority constituencies, ensuring Malay parliamentary dominance.

UMNO and the other parties also agreed that the police and army would continue to be largely Malay. Finally, it was agreed that a concerted effort would be made to raise the economic position of the Malays.

In return for going along with the safeguards for the Malay position, what did the Chinese receive? Laws made it possible for virtually all immigrants to become citizens. By the 1959 election, the Malay percentage of the electorate had dropped from 80 percent to about 58 percent as many immigrants had become citizens under the new laws.

A second concession was the right of immigrant races to maintain educational institutions in their mother tongues. It was agreed that at the primary school level, the Chinese and Indians could study in Chinese- and Tamil-language schools. This concession and the guarantee of religious freedom were key to assuring the immigrant races that they could maintain and pass on their own unique cultures.

Informally, it was agreed that there would be no large-scale attempt by the government to redistribute wealth. Private property would be respected and, not withstanding the government’s affirmative action programs, free enterprise would continue. Attempts to lift the Malays economically at the expense of the Chinese and Indians would be avoided.

In a nutshell, the leaders of UMNO, the MCA and the MIC had traded Malay political domination and special rights for immigrant citizenship, a role in the political process and the right to practice their cultures. The Malay elite had retained the right to rule and lead their community to higher living standards, while the Chinese elite had protected their residency and the vested interest they had in the economic future of Malaya.

Many voices in the three communities were not heard when this deal was struck. Many of the ordinary people in Malaya felt they had been sold out by their leaders. Many Malays felt that the Chinese had been granted too large a political and economic voice, while many Chinese felt they had been granted second class citizenship. When they made their voices heard later on, the fabric of the original agreement would unravel, but for the moment, enough had been done to ensure the transfer of power from the British to the Malayans in a stable, optimistic environment.

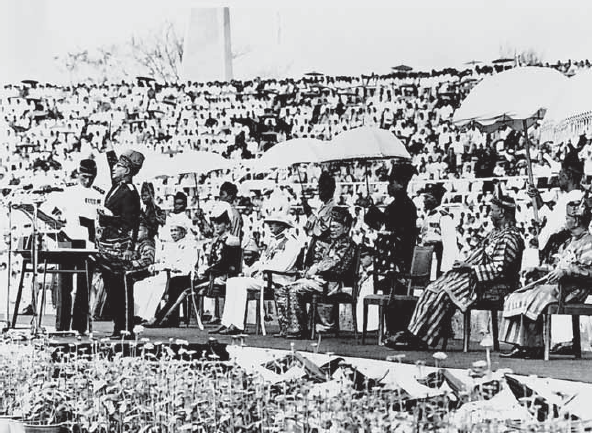

The Tunku declares independence on August 31, 1957.

On August 31, 1957, the Union Jack was lowered for the last time in Kuala Lumpur, and Tunku Abdul Rahman took the oath of office as the first prime minister of an independent Malaya.

The British legacy was mixed. The British left behind a prosperous country with tremendous potential. A modern, Western-style democracy was in place with an infrastructure unmatched in the region. There was order and stability in the country, and the races seemed to be cooperating to lay the foundations for independence. Most saw a bright future for the new Federation of Malaya. On the other hand, there were forces at work beneath the surface that were also Britain’s legacy. Economic and political inequalities among the races were time bombs waiting to go off.