1

A Death and a Birth

Alain Locke rose early on April 23, 1922, a cool, clear Sunday after Easter in Washington, D.C. It was also the Sunday before his mother’s sixty-seventh birthday. He woke her, helped her dress, and then served breakfast. Afterward, he read to her from the Sunday edition of the Evening Star. Headlines announced that the secret Russian-German economic pact threatened to break up the Genoa Conference, the Pan-American Conference of Women proposed a League of Nations, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the Sherlock Holmes author, was to speak in Washington as part of his nationwide tour. Only the last caught her interest—she and her son shared an interest in psychic phenomena, and Sir Conan’s lecture on spiritualism was sure to be provocative and revealing. She dozed off when Alain launched into the details of his particular interest, the struggle between Germany and the Allies for trading rights with newly Communist Russia.1 That afternoon she was “stricken,” in the words of her son. He laid her down in her bed, where, at 7 p.m., she died, leaving her son of thirty-seven years alone in their home. The next day he taught his philosophy class at Howard University as usual. Only later in that day did students learn that Dr. Locke’s mother had died. Others learned of her passing from Tuesday’s Evening Star, which carried the death notice, “Locke. Sunday, April 23, 1922 at her residence, 1326 R Street NW, Mary Hawkins, beloved wife of the late Pliny Ishmael Locke and mother of Alain Leroy Locke. Last reception to friends Wednesday evening, from 6 to 8 o’clock, at her residence.”2

A student of Locke’s, poet Mae Miller Sullivan, recalls that her father, Kelly Miller, a dean at Howard University, hurried her mother that Wednesday evening saying, “Mama, get your things together. We mustn’t be late for Dr. Locke’s reception for his mother.”3 The Millers and other friends of the Lockes climbed the stairs to the second-story apartment on R Street to find the deceased Mary Locke propped up on the parlor couch, as though she might lean and pour tea at any moment. She was dressed exquisitely in her fine gray dress, her hair perfectly arranged. She even had gloves on. Locke invited his guests to “take tea with Mother for the last time.”4 After a short visit, most left quickly. On Thursday, Locke had her cremated and, according to his friend Douglas Stafford, he kept “the ashes of his mother reposed in a finely embellished casket” on the White grand piano in his home.5

The story of Locke’s “wake” for his mother became part of the folklore of Washington’s middle class. On the one hand, it was common practice in the early twentieth century for the deceased to be laid in state in a bedroom to be visited by family friends. It probably did not surprise close friends that Locke had placed gloves on his dead mother’s hands, since they were part of proper attire for tea in a Victorian household. On the other hand, having her seated and dressed as if alive struck most visitors as wildly eccentric. It was known that Locke and his mother were close and that the two kept pretty much to themselves. When they did entertain, it was together. Dr. Metz T. P. Lochard, a colleague and close friend, recalled many Sunday strolls and stimulating conversations with Locke and his mother, whom Lochard recalled as a refined, cultured, and well-read woman. “She had all the ways of an old English aristocrat. She was gentle, affable, kind, tolerant and indulgent. That’s why Locke was so attached to her.”6 The obituary notice that Locke published in the Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), said Mary Hawkins Locke came from “an old Philadelphian family.”7 Hers was a well-respected family whose members had had close ties with the upper class in Philadelphia.

Such closeness between sons and mothers was not unheard of in the early twentieth-century Black community, almost as compensation for the disruption of maternal relationships under slavery. Certainly that “peculiar institution” had not allowed slave mothers to provide anything like the undivided attention Locke had enjoyed. The post-emancipation community tended to idealize mother-love, especially among the northern bourgeoisie, where two-parent family relationships symbolized class respectability and the nurturing, caretaking mother anchored Victorian families. Mother was a boy’s most reliable companion, especially around the turn of the century when male mortality rates were high. It was no accident that Langston Hughes’s famous poem about a boy’s struggle to survive is dedicated to his mother, who consoles the son by sharing her burden with him—“Son, life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.”8

Life had been no crystal stair for Mary Locke, either. After her husband’s death when Alain was six, she had taught school days and nights, and in the summer, to earn enough to support the two of them during his long educational tenure. Despite constant work, Mary had showered him with the kind of close attention, constant encouragement, and special nurturing that this tiny, physically delicate, often sickly child demanded. He, in turn, responded to this outpouring of care by taking on and living up to her dreams and high expectations. He had excelled first at Central High in Philadelphia and then again at Harvard College, where he won several scholarships and graduated Phi Beta Kappa. In his final year, he had been the first African American to be chosen as a Rhodes Scholar to Oxford. After further study at the University of Berlin, he had returned to the United States and become a professor at Howard University.

Upon her retirement in 1915, Locke took his mother with him when he returned to Harvard for graduate study that led to his PhD in philosophy in 1918. Afterward, they lived together in his second-story apartment in Washington, D.C., and he filled her declining years with the kind of reading material and trips to museums and concerts that she had lavished on him as a child. If from her deathbed, she had surveyed the work she had done, she would have concluded it was a job well done. In turn, Locke’s wake to his mother and his tribute to her in the Crisis testified to how much he valued her and how deeply he mourned her.9

Had Locke not chosen to invite members of the community to his bizarre public wake, then perhaps his relationship with his mother and her dominating role in his life would have gone unmentioned. Instead, people who knew nothing else about Locke’s life and work knew of the tea with the mother propped up as if alive. Locke’s obsessive attention to detail in staging the wake, down to the finery of the lace on her dress and the placing of gloves on her hands, tended to caricature his mother in the very act of honoring her, bringing his high-minded, spiritual, self-sacrificing love down to the level of common snicker and unguarded amusement. Such adulation forced the community to confront an unsettling issue. In one theatrical gesture, Locke had symbolized the problem of an entire generation of young men and women who, because of their “proper honoring of elders,” felt stifled by both their parents and the Victorian fetishes of decorous living, social propriety, and group respectability. Like others of his talented generation, Locke had been unable to separate from his mother. Even death did not finally sever that cord.

Alain Locke was unknown to the general public, in part because he had devoted much of his adult life to a quiet caring for his aging mother, but also because he had failed to take on a major role as a Black intellectual, such as his forerunner at Harvard and Berlin, W. E. B. Du Bois, had done.10 Locke had avoided involvement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), had avoided involvement with more radical organizations like Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and especially avoided such socialist organizations as Hubert Harrison’s International Colored Unity League (ICUL). He did not like civil rights movements or more accurately civil rights organizations, did not like the whole practice of protest that had already become definitive in Black political advancement in the early twentieth century. Locke was not one to be found in a march, or a riot, or demonstrating to bring about change—even of wrongs he agreed were despicable. Born and bred in Philadelphia’s Black middle class, Anglophile in dress and class snobbishness, a man who seemed to represent in his learning and bearing an old world Black tradition that no one knew existed, he was a fish out of water in most situations of mass political organization because of his class consciousness and sense of distance from most Negroes. And for years he had been insulated from any criticism of this lack of public involvement in Black affairs by his caring for his mother. Now, that excuse was gone.

There was one more thing. He was a tiny, effeminate, gay man—a dandy, really, often seen walking with a cane, discreet, of course, but with just enough of a hint of a swagger, to announce to those curious that he was queer, in more ways than one, but especially in that one way that disturbed even those who supported Negro liberation. His sexual orientation made him unwelcome in some communities and feared in others as a kind of pariah. And early on he had decided that working with masses of Black people in close quarters like mass movements rushed scandal and exposure he could not afford. So, he kept his distance from the masses of Black people, the working and lower-middle classes of the race, those his mother had taught him to avoid anyway.

But Locke did something remarkable with his alienation. He decided to use art, the beautiful and the sublime that nurtured his and his friends’ subjectivities in a world of hate, to subjectivize the Negro, to transform the image of the Negro from a poor relation of the American family to that of the premier creator of American culture. Rejecting the notion advanced by W. E. B. Du Bois that the political struggle for civil rights should be the focal point of Black intellectual life, Locke argued that what really made the Negro unique in America was the extent to which Black people had produced the only indelible art that America had produced. At a time when radicals argued that the rioting of Blacks in Chicago in 1919 against racial attacks by Whites was the essence of the New Negro, Locke argued that a new consciousness had emerged since World War I of positive possibility for Black people in the twentieth century despite the constraints of American segregation. At a time in the early 1920s when the popular discourse about Negroes even in liberal progressive circles was that of a tragic problem of American democracy that needed fixing, Locke created a counter-image—that of a New Negro who was reinventing himself or herself in a new century often without the help of Whites. The New Negro was a cultural giant held down by White Lilliputians and all that was needed was for this giant to throw off the intellectual strings that bound this intellect to self-pitying despair about Black people’s plight in America, and assume his or her true role—as the architect of a new, more vibrant future called American culture if those in his or her path would just get out of the way.

In the 1920s, these views were radical, but Locke found a way to advance them by using Beauty to subjectivize Black people. By focusing his advocacy of the New Negro on art, literature, music, dance, and theater, arenas in which queer Black people of color like himself found sanctuary, Locke shifted the discussion of the Black experience to the creative industries that even racists admitted were mastered by Black people. The spirituals, to take his favorite example, had transformed Anglican hymns into something fundamentally American but also transformed the attitudes of Whites and Blacks who heard them. "Afro-Americans," a term he used frequently, manifested a creative genius from the moment they landed in the Americas by taking a foreign culture and making something new out of that. The enslaved were just that—temporarily bound but spiritually free people, who, despite earthly oppression, could create works of beauty, as the “sorrow songs” had shown. Those songs showed Locke, a philosopher, that a consciousness existed even in the most oppressive people who could change their perspective on their life through art. Beauty, in other words, was a source of power for it could transform the situation of Black people by transforming how they saw themselves. By focusing on Black cultural production, Locke sought to revitalize urban Black communities, elevate Black self-esteem, and create a role for himself as a leader of African-derived peoples.

Something about the death of his mother in 1922 released him to take on this daunting, Herculean task. Her death loosened the grip of her Black Victorian culture on his thinking, but it also left him with a crushing longing for the unconditional love she bestowed on him. The process was not immediate or easy. At first he was inconsolable, dogged by pangs of loneliness and anxiety that left him wandering the streets of Washington, D.C., with a faraway look in his eyes. Although he continued to teach classes, those who knew him better realized that a sharp pain lingered behind the hungry look in his eyes. One friend in particular offered herself as a kind of mother-surrogate and helped Locke through this difficult period. That woman was Georgia Douglas Johnson, a well-known Washington, D.C. poet, who was married to a prominent attorney and the Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. Most important, Mrs. Johnson was the organizer of the “Saturday Nighters,” an informal salon of writers who met at her home to eat, drink, and talk literature. She nurtured the controversial bright lights of literary Washington, such as Jean Toomer, one of the most experimental and respected novelist of the Harlem Renaissance period, and Richard Bruce, the enfant terrible whose drawings and short stories elaborated on the theme of male homosexuality. Johnson was able to provide a literary family for these young rebels because she identified with the generational struggle of youth to free itself from the constraints of living in aggressively assimilated, bourgeois Washington. She believed passion, however controversial, was better than cold Victorian moralism, and as she watched Locke trudge the steep hill toward Howard University every day, she felt the pain of his loss. Moreover, as a woman married to a strict Victorian twenty years her senior, a man who derided her activities with “artistes,” Johnson could identify with the generational crisis Locke was undergoing.

Johnson began to help Locke to live without his mother when she wrote him, “If you should ever take sick suddenly in the night or day, just have some one in the house phone or call me. I shall be happy to come day or night regardless of the night work I’m doing. I mean this and want you to feel that you can count on me at any time. I think your mother would like me to say this to you.” At the same time, she encouraged his dark explorations of the macabre when she continued, “Please send me a copy of the poems you read to me … especially the one about the worms going through skulls, etc.” Johnson was also experimenting in her poetry, reaching toward the controversial issues of sexual frustration, spiritual death, and personal renewal she would tackle effectively in An Autumn Love Cycle (1927). Perhaps more than Locke’s other friends, Johnson sensed that an internal struggle waged inside him between the temptation to remain a Victorian or move forward into uncharted waters of modernism—a struggle waging in her as well. Encouraging him to go to Europe, she recalled, “I have remembered the expression in your eyes. I do hope that you will see many happy scenes that will delight and draw you into forgetfulness.”11

The next time Georgia Douglas Johnson and Locke’s other friends heard from him he was in Berlin. Locke had left New York on June 22, 1922, for Liverpool and had gone immediately to Paris where, on walks up and down the Champs Elysees, he recalled earlier sojourns taken there with his mother. But it was in Berlin, where in earlier years he had studied, that Locke seized on the rewards of living without his mother. He delved into Berlin’s pulsating nightlife, its bohemian artistic community, and its perplexing double infatuation with urban modernism and rural romanticism. He emerged with a vision of a renaissance of the modern spirit he wanted to inspire in urban America. Locke saw Europe had changed dramatically since he and his mother had last visited in 1914. Here was a Europe alive to African culture, as reflected in the flock of artists who daily went to ethnological museums to study African sculpture for its lessons in cubism and expressionism. It was in Berlin that Locke was re-exposed to modernism and began to conceive for himself a new mission—to lead a new African American modernism that would reject the stuffy, rule-bound, repressed Victorian culture he had grown up under and in many respects epitomized. When he returned home that fall, Locke began to envision a new, more public role for himself, freed from the fetters of his past and his caretaker role with his mother.

There were self-destructive temptations in this new freedom as well. For a closeted homosexual, his mother’s departure meant that he could delve into the nightlife of Berlin—and New York—with an abandon not possible before. Was that the path forward, simply to immerse in the sexual pursuit of young men? Or was there something of the older tradition of discipline, self-management, and cultural aspiration that he needed to allow him to become something more powerful than simply a college professor on the make? Even if he turned away from the pursuit of sex for sex’s sake, the deeper problem remained: how was he going to become influential in a Victorian world that was patriarchal and heterosexual? Locke avoided groups, especially Black grass-roots organizations and establishment civil rights organizations like the NAACP, because of his fear that his sexuality would be exposed. Black middle-class politics was fundamentally patriarchal and heterosexual, revolving around social occasions where the leaders, always male, and their wives dominated the political agenda with their socially conservative narratives about “respectability” and “representativeness,” and the demand that the race “put its best foot forward” to combat White discourses that Black people were fundamentally subhuman. Behaving heterosexual was part of the price of admission into these organizations, and having Locke roving around meetings with an eye out for attractive young men was an explosive situation. That Locke had published his mother’s obituary in the NAACP’s Crisis was ironic, because Locke was not a member of that organization, or a fan. Yet, the Crisis, edited by America’s premier intellectual, W. E. B. Du Bois, was one of the very few journals in which art and culture was reviewed, discussed, and promoted seriously.

Alienated from the community surrounding bourgeois and grass-roots movements of race advancement of his time, Locke decided to create an alternative community of straight and queer people built around queer people’s love of art and culture. In this work, Georgia Douglas Johnson modeled what he wished to foster as much as the Berlin gay community. His new community would be an open secret, an art movement eventually called the Harlem Renaissance, that could accept him and others like him who built a sense of belonging to one another out of the love that aesthetes and dandies like him had privately shared. His coming out—to the extent that that was possible—was to become a public player in creation of the subjectivity that would come to dominate American culture of the twentieth century. Though still closeted, still afraid of exposure and arrest, he nevertheless became a public intellectual while remaining an active homosexual. He could not build a public civil rights movement like Du Bois’s to transform the material or even the political condition of the Negro, but he could build an aesthetic movement to transform the image of the Negro as a discursive sign in American culture. He could do that because he fostered a community of people who shared a belief that the Black experience of America could foster great art.

Still handicapped psychologically by his dependence on a mother figure even after his mother’s death, Locke found that he could be a nurturing hero by editing and advancing the work of more creative people than himself. Even before his mother’s death, he had begun to privately counsel and promote new talents like Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Ann Spencer, and Georgia Douglas Johnson herself. After his mother’s death, he would stake his claim to being an influential Black intellectual on them, defying the notion that the advancement of Black interests was mainly a political or economic undertaking. A tempered radical, Locke took what he loved—and had shared with his mother, a love of art—and turned it into an intervention—a means for a catharsis in the American soul, not the basis of propaganda for the race, as Du Bois later advocated. His really radical notion was that the Negroes had to transform their vision of themselves, to become New Negroes, and see the world with a new vision of creative possibility, if others were going to treat them differently, with more dignity and respect that the race so richly desired. Justice, he believed, would follow upon seeing, for the first time, that the Negro was beautiful. He would re-create politics by teaching a new generation of Black artists that they had a lofty mission—to march the Negro race out of the Plato’s cave of American racism and allow them to see themselves through art as a great people. By subjectivizing the Negro, Locke believed the New Negro artists would change the calculus of American life and make Negroes the initiators of progressive change, not the recipients or dependents of it.

Here was that deeper irony Locke’s life always conveyed—here was a man who was deeply dependent on other people who preached independence and self-determination as his aesthetic politics. He was a deeply conflicted man, who operated as a loner, who befriended but often abandoned writers, artists, and lovers out of fear of being abandoned himself. He could be selfish, untrustworthy, vindictive, and vicious, but he could also be the sweetest of persons, who devoted himself to students, helped less fortunate, often destitute artists survive, and created the rationale, along the way, for contemporary Black art and literature. Culture would be his business.

Mary would live through him, but where she had worshipped culture as an escape from the experience, he would use culture to return the artist to the Black experience of suffering and travail that America had been for generations, and transform that experience into something beautiful. He would take a dying, decorative, bourgeois culture and transform it into a new, living aesthetic that included the folk culture of the masses and drew on the African ancestral culture. Three years after his mother’s death, he wrote a clarion call to the young Black writers in Philadelphia, his hometown, trying to break free as he had just done himself.

I was taught to reverence my elders and fear God in my own village. But I hope Philadelphia youth will realize that the past can enslave more than the oppressor, and pride shackle stronger than prejudice. Vital creative thinking—inspired group living—must be done, and if necessary we must turn our backs on the past to face the future. The Negro needs background—tradition and the sense of breeding, to be sure, and it will be singularly happy if Philadelphia can break ground for the future without breaking faith with the past. But if the birth of the New Negro among us halts in the shell of conservatism, threatens to suffocate in the close air of self complacency and snugness, then the egg shell must be smashed to pieces and the living thing freed. And more of them I hope will be ugly ducklings, children too strange for the bondage of barnyard provincialism, who shall some day fly in the face of the sun and seek the open seas. For especially for the Negro, I believe in the “life to come.”12

Locke became a “mid-wife to a generation of young writers,” as he labeled himself, a catalyst for a revolution in thinking called the New Negro. The deeper truth was that he, Alain Locke, was also the New Negro, for he embodied all of its contradictions as well as its promise. Rather than lamenting his situation, his marginality, his quiet suffering, he would take what his society and his culture had given him and make something revolutionary out of it.

Locke did it out of his need for love. This need led him into dangerous yet fulfilling relationships with some of the most creative men of the twentieth century, but also drove him to something else—to try and get that love from Black people as a whole, by doing all he could to gain their approval, win their recognition, even though he could never fully experience it for fear of rejection. As such, he remained a lonely figure, but also a figure of reinvention, for his message was that all peoples, especially oppressed people, had the power to remake themselves and refuse to be what others expected them to remain.

In his mother’s end was his beginning. Mary had mothered him. Now, he would mother a movement.

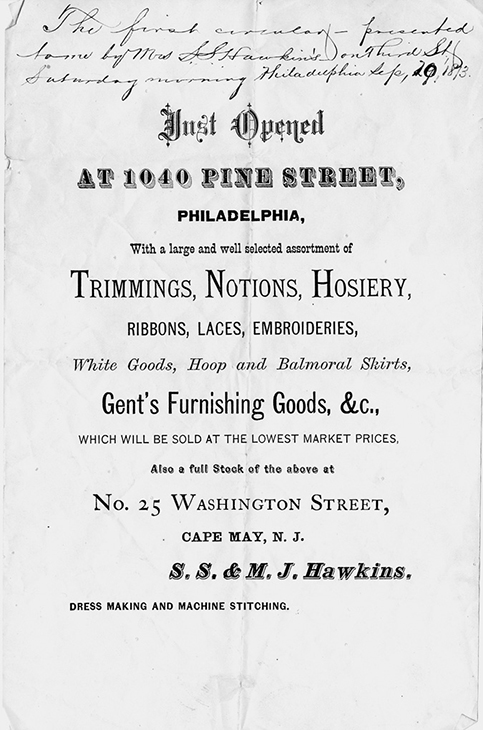

Circular for Opening of Sarah Shorter Hawkins store in Philadelphia, 1873. Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.