2

A Black Victorian Childhood

Alain, christened Arthur LeRoy Locke at birth, was a sickly, tiny baby. He was not expected to live. Born on September 13, 1885 (though he publicly gave his birth date as 1886), Locke contracted rheumatic fever at birth, and cried and gasped for breath during attacks.1 That entire first year the family, especially his mother, Mary, lived with the terror that the next attack would kill him. Mary spent every possible moment with him, leaving household and shopping duties to his grandmothers. In her nurture of her son, Mary found fulfillment she lacked in her roles as teacher, wife, or daughter. He needed her and seemed strengthened by her bathing, stroking, and breastfeeding. Even after the crisis had passed, Mary remained extremely protective of her “one and only.” She had nursed him back from death and she kept vigilant watch lest some new, unforeseen illness take him away. By his third year, his health had stabilized even if the economic situation of a relatively modest Black middle-class family had not.

Roy, as he was called as a child, had been born at home on South 19th Street, located at the edge of Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, a Black residential neighborhood. W. E. B. Du Bois, the sociologist hired by the University of Pennsylvania in 1897 to study living conditions in Philadelphia, described the neighborhood in which Locke was born:

Above Eighteenth, is one of the best Negro residence sections of the city, centering about Addison street. Some undesirable elements have crept in even here … but still it remains a centre of quiet, respectable families, who own homes and live well.2

Locke’s birthplace and two successive family residences at 1574 South 6th Street, where they moved in 1890, and 2221 South 5th Street, where they lived after 1892, represented the epitome of rental Victorian furnishings available to the “better classes” of Negroes in Philadelphia. Mary, Pliny, and the two grandmothers lived in six rooms on 19th Street. Mary tastefully decorated the second-story flat with furnishings from her mother’s home and with curtains and upholstery coverings she and her mother made. A White visitor to the Locke household in 1885 would have been struck by how closely these accommodations resembled those of middle-class White Philadelphians.

Charles Shorter, Alain Locke’s maternal great-grandfather, was an eighteenth-century Black success story. A hero of the War of 1812, he won the admiration of city fathers when he captured a British ship off Philadelphia’s harbor and turned it over to the Americans. After the war, Shorter amassed a small fortune as a sailmaker and used much of his money to purchase books for the Library of the Free African Society founded by Absalom Jones and Richard Allen in 1787. In the aftermath of the War of 1812, a core group of Black ministers, entrepreneurs, political aspirants, educators, and artists emerged who inhabited the same social class and shared a collective vision of forging a Black community devoted to self-help, classical education, and sustainable middle-class families. This elite group comprised people like the wealthy sailmaker James Forten; ministers Richard Allen and the self-educated Absalom Jones, who founded independent African Methodist churches in Philadelphia; the political leader Robert Purvis; entrepreneur Henrietta Bowers; and Locke’s paternal grandfather, Ishmael Locke, the first teacher at one of the first schools for Black youth in the United States, the Institute of Colored Youth. In Black Victorian Philadelphia, an array of churches, benevolent societies, literary and historical societies, the Home for Aged and Infirm Colored Persons, and the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital all attested to the ability of the Black elite and middle class to found institutions that ministered to their needs and to those of the lower class. In the process, Black Philadelphians developed a distinctive urban style. Mirroring the Quaker ideology that an enlightened life was possible on earth, the Philadelphia Black elite prided itself on its command of English and Anglo-American culture and turned that culture to its own purposes of group advancement and individual accomplishment. A sense that educated Negroes were at least the equals of their White peers in their mastery of English literature, religious doctrine, and Victorian mores and manners pervaded the Black aristocracy, as they sought to call themselves.

Ishmael Locke was a model for his grandson even though he never knew him. Born in Salem County, New Jersey, in 1820, he was a “pioneer educator,” one of the most respected Black teachers in the antebellum North. Ishmael carried a letter of recommendation with him to Philadelphia in 1844 that stated, “Ishmael Locke is of good character; served as a teacher for 2 1/2 years—taught reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and astronomy … in the school for coloured children in this town.” Having a letter from the White elite of Salem was crucial to Ishmael’s ability to secure employment as a teacher among the Quaker elite of Philadelphia. The letter’s White signatories especially noted his “habits of the strictest morality, his personal order and decorum,” and “the reputation he has obtained for intelligence and literary attainments; [both] have secured for him the confidence and esteem of our community.” Another recommender noted Ishmael was “a most efficient and excellent teacher, having advanced his pupils rapidly by discipline in the school, and greatly improved their conduct and condition by the force of good example and precept.”3

Just two years after Ishmael Locke arrived in Philadelphia, working-class Whites rioted and attacked Black churches, schools, and meetinghouses on the very avenue, Lombard Street, where Ishmael’s new school stood. Hired as the first principal of the Quaker-founded Institute for Colored Youth, a teacher’s college, Ishmael was charged with inculcating in rising young Blacks the gentlemanly values of the Yankee middle class, precisely those behaviors and attributes that attracted the ire of the rioting Irish working class. Black elite institutions were the prime targets of White rioters, who felt that Blacks like Ishmael were too successful at assimilating upper-class Anglo-American values and too “uppity” because of it.

Ishmael escaped attack, partly because he and his wife, Mathilda, resided in New Jersey in 1846, having purchased a home in Camden. Ishmael may have continued residing in New Jersey because of his political stature in its Black community. Certainly it was not because New Jersey was a less racist state than Pennsylvania. Both states took voting rights away from free Negroes who had voted for years because it was coupled to Democratic Party demands to establish universal suffrage for White males by eliminating property qualifications for voting. Ishmael Locke was a member of the New Jersey “Coloured Convention” that protested this disenfranchisement of Blacks and coauthor of the petition to return the vote to New Jersey’s Black population. Tellingly, he argued that free Negroes deserved political representation because of their property, education, and cultivation—their assimilation of Anglo-American middle-class values. The petition read:

Being endowed under the blessings of a beneficent Providence and favourable circumstances, with the same rationality, knowledge, and feelings, in common with the better and more favoured portions of civilized mankind, we would no longer deride you and ourselves by exhibiting the gross inconsistency, and by so far belying the universal law and the great promptings of our nature; cultivated as we claim to be, as to have you no longer suppose that we are ignorant of the important and undeniable fact that we are indeed men like yourselves.4

Ishmael’s faith that culture and accomplishment could triumph over racism lay in the Black Victorian ideology of educated African Americans that held sway for over a century. “Victorianism” came to be the term used for a set of rules for public and private life that characterized middle-class status. On the one hand, sexual prudishness, verbal and literary censorship, and personal self-discipline signified that one was “civilized.” On the other, Victorians allowed the most conspicuous display of wealth through dress and public parade. By the time of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, a Victorian style had crystallized into a public pedagogy of how the lower and working classes, and minorities and colonials, ought to act if they wanted to be considered middle class and civilized.

As Locke observed in his study of imperialism, Victorianism abroad created desire in the subject populations to emulate British culture to gain admission to civilization. Something like that psychology operated among Black Victorians, who inhabited London, Boston, Washington, D.C., and especially Philadelphia, where increasingly, educated free Negroes grew up imbibing the nineteenth century’s Anglo-American love of class, home, and strict public behavior. Ishmael’s Black Victorianism boiled down to three things: culture, education, and a commitment to the race. Black Victorianism thus had an affirmative twist, to use civilized ways to defend the race from attack and improve the lifestyle of barely free Negroes in the antebellum North.

Black Victorianism barely hid its deeper tragedy. Racism was not restrained by proof of cultural equality or performance of middle-class rituals. The vote was not restored to New Jersey’s Blacks, and the citizenship rights of northern free Negroes continued to decline in the 1850s, despite numerous manifestations of self-improvement and successful social integration. Economic conditions for the tiny Black middle class worsened, due in part to increasing economic competition between Blacks and working-class Whites. Ishmael Locke experienced difficulties, forcing him to leave the job in Philadelphia in 1850, the year his first son, Pliny, was born. In 1851, another son, Phaeton, was born, but before that year was over, Ishmael had died of tuberculosis, leaving his widow to rent out the home in Camden and live with relatives in Philadelphia.

Like his grandfather, Locke would have close ties with the Yankee elite throughout his education and career, while lacking their financial security. Like his grandfather, Locke would base his appeal for freedom and justice in American life on the culture of African Americans, in part because both the masses and most of the Black elite lacked the economic resources of other middle-class Americans. But Locke would subtly resent his paternal grandfather and father because of their economic situation, while subtly favoring his maternal grandmother and mother, because they were from the entrepreneurial side of Black Victorianism. A tension resonated in Locke throughout his life between the political progression of his paternal grandfather’s side of the family that was committed to race service and ignored the financial consequences and the economically relentless middle-class side of his maternal grandmother’s family that was always seeking money. As an adult he often stated that he had to make Black advocacy pay. The Black Victorians had all the ingredients of an elite Anglo-American lifestyle except the most important, money, and it caused Locke a great deal of pain throughout his life.

When Locke remarked with pride years later that he came from a family that was “fanatically middle class,” he alluded to the price Black Victorians like him paid for striving to be equal to Whites culturally while barely making a living as educators. Constantly scrutinizing one’s dress, one’s speech, and one’s deportment in public meant that self-scrutiny dominated their innermost thoughts. After his mother’s death, Locke recognized this internal policing as crippling to his and other Black artists’ aspiration to create a distinctive voice in American culture. For most of his life, he remained a Black Philadelphian—a brilliant son of a middle-class culture with no future, who admitted his life of the mind had been shackled by an upbringing that made him “paralyzingly discrete.”5

The one person in Roy’s family seemingly not “paralyzed” was his father, Pliny Ishmael Locke, a man “of small stature and slight build,” according to Christopher J. Perry, the editor of the Philadelphia Tribune, who called the senior Locke a born leader of men. Perry published his account of Pliny Locke’s life in his column “Pencil Pusher’s Points,” one of the more popular items in this local Black newspaper. Told for the benefit of younger readers, the story unfolds that Pliny, after first excelling in and then teaching at his father’s school, the Institute of Colored Youth, “joined the army of educators to the Southland,” only to return to Philadelphia and become the first Black civil service employee in the Post Office in 1883. Subsequently he was appointed a clerk in the customs house and an inspector in the gas department. Pliny was president of local political organizations such as the Quaker City Beneficial Association and was very active in city politics, receiving a commission at the customs house.6

According to Perry, Pliny “was born to command, in whatever field he worked men seemed to feel a confidence in him and were content to be guided by his judgment. All of his teachers conceded to him a wonderful mind and felt that had he been at Harvard, Yale or any of the great institutions of learning, he would have been in the forefront of the strongest.” But Pliny’s most striking characteristic was his courage:

To illustrate the phase of the grit and resourcefulness of the man is to tell the story of his first morning in his new charge [as a teacher at the South Chester Bourory School for Blacks]. He was as quick at perception as of action, and saw a recalcitrant spirit, who was likewise dominant. He rang the bell for order, and as quick as a flash jumped from the platform, grasped the big lad by the throat, threw him down; and then called the rest of the startled scholars to order. There was a complete hush and he let go of the refractory spirit, only to throw him out of the door a minute later. After that order was supreme in his school.7

As Perry observed, Pliny was “brave, even to the point of indiscretion at times.” For example, while working as a bellman in a hotel one summer, Pliny wrote: “how I chafe under the regime of ignorant negroes and domineering Whites, who seem to think that every negro is a boy and a dog—Hoyt, one of the room clerks and myself have had it several times and last night the man who has the newsstand and myself had a warm time of it.”8 While a government employee in Washington, Pliny wrote to Mary that he had let a White congressman have a piece of his mind when the latter claimed Blacks ought to be grateful and acquiescent to the Republican Party after what Lincoln’s party had done for them. “You can imagine how well such talk accorded with my ideas—I spoke as I felt and he seemed utterly surprised that I should do so.”9 Pliny exuded the attitude of self-assertive Black manhood characteristic of the Reconstruction Era, when Blacks fought for the right to vote and demanded equality with Whites.

The immediate problem that had faced Pliny and other graduates of his father’s school in the Reconstruction period was not the right to vote but the right to work. Graduating at the top of his class in 1867, he stayed on two additional years to teach, and then, at nineteen years of age, left Philadelphia bent on carving out his own reputation as an educator. Pliny and Mary probably met at the Institute during his two-year teaching stint; he may have been Mary’s teacher. When an offer came from the Freedmen’s Bureau in Washington to start a school for Blacks in rural East Tennessee, he jumped at the chance. At least working in the South would be better than joining the ranks of other unemployed graduates of the Institute for Colored Youth. Although the Institute was producing excellent teachers, the school boards of Philadelphia, Camden, and other New Jersey municipalities had established very few schools for Blacks.

Pliny arrived in Tennessee at a time when the Freedmen’s Bureau, created by Congress in 1865, had become a shadow of its former self. By January 1869, the combined opposition of White landowners, poor Whites, Conservatives, and the Ku Klux Klan had forced severe cutbacks in the amount of food, education, and medical attention the freedmen received. Fortunately for Pliny, his commission directed him to start his school in East Tennessee, which had escaped the Klan’s reign of terror that had devastated Blacks in the plantation counties of West Tennessee.

Nevertheless, East Tennessee was not free of White hostility. As he wrote to Mary, “There are plenty of outspoken and bitter rebels and negro haters here. They hate the sight of a northern man.” Pliny was appalled at the conditions under which Blacks lived where he started his school. “I am now writing in a house that people north would scarcely keep their horses in.”10 A month later he confided that his school had managed a “daily attendance of about 30 of the most uncouth, ugliest and greasiest mortals you ever beheld. I am indeed engaged in the arduous duty of instilling knowledge in the minds of true representatives of Ham or of blackness. But whether they will ever achieve renown or not I can not say.”11

Pliny was not alone among Reconstruction-Era northern African Americans in his distaste for the Black masses, because their middle-class backgrounds made it difficult for them to identify with the aspirations, usually for literacy and for land, of the rural freedmen. The Reconstruction-era congressmen paid a price for their bias—most lost political power, because they could not hold onto their lower-class Black constituency and could not gain White loyalty. Whenever Pliny took positions of public leadership, he would either be thrown into racial conflict with Whites, who resented him because he was Black, or into class conflict with lower-class Blacks whose values, habits, and attitudes were repulsive to him. In his letters to Mary, Pliny derisively termed poor Blacks in Tennessee “kids” and seemed to resent rural Blacks as much as the “Negro hating” poor White rebels. Like most Black Victorians of his day, Pliny also disliked poor Whites. Yet the consequence of his class bias against poor Blacks was more serious since it meant he would never be able to build an enduring political base as a Black leader.

Added to race and class conflict was the regional problem of living in the South, something Pliny found especially disagreeable. He soon became ill, and in April 1869 fell from a horse, severely injuring his arm. Although he resolved to stay for two years, that May Washington notified him that his position would be terminated. After a brief return to Philadelphia, in October 1871, Pliny accepted a clerk position in the Washington office of the Freedmen’s Bureau. He arrived in Washington, D.C., to find that John W. Cromwell, a classmate at the Institute for Colored Youth, had recommended him to John Langston, the noted Afro-American lawyer and dean of the Howard University Law School. Shortly after a personal interview with Dean Langston, Pliny enrolled in law school, obtained housing at the university, and settled down to work in the Bureau and as Langston’s personal secretary.

Pliny’s move to Washington strained relations with Mary. She felt rejected when he left Philadelphia a second time. Although she knew that law school and a government clerkship were excellent opportunities for him, she had secretly hoped he would find employment in or near Philadelphia. Moreover, his infrequent letters showed that Pliny was becoming a rogue about town, who sported a cane and kid gloves and flirted with Washington ladies. Mary began to believe that their courtship would never result in marriage.

Ironically, in September 1872, just after his letters began to open with “my dearest love,” Pliny stopped writing to Mary. Mary stopped corresponding as well, which elicited from Pliny the following note:

I see from your account that in the case of Love vs. Pride, the defendant won but owing to some mischance he failed to get damages and thus I lost the pleasure of receiving a letter. I do not blame you but I am certainly sorry that you were prevented from mailing it. Am I such an enigma and so little understood, that when flushed with joy at long-deferred success, that I am thought to be inapproachable? I have more cause to ASK forgiveness than to grant it, for after all am I not the cause of that seeming lack of confidence? … Did brute and beast and villain again become synonyms with Locke?12

Pliny had stopped writing after he lost his job at the Freedman’s Bureau. When he did write he said that “pride would not let me open my heart to any, not even to you, my loved—yes, dearly loved one.” Although Pliny secured another clerkship in the Treasury Department, his economic situation and their courtship remained rocky for the next three years until Mary wrote him in February 1875 that he was forgiven and that she wanted to share his sorrow as well as his success. This proud man struggled with a melancholy streak. With Mary, especially, who was not only of a higher social class but also a fault-finding lover, Pliny felt that he had to be a “tough-minded” success story to be accepted by her and her mother.

Class and gender tensions dominated Pliny’s long-distance courtship of Mary Hawkins. To Pliny, Sarah Shorter Hawkins (Mary’s mother) was everything he resented about Philadelphia upper-class society. Sarah embodied the sense of superior status through connections with wealthy Whites that characterized the Philadelphia Black Brahmins. In fact, she did not even consider herself Negro, preferring to term herself a free person of color. She continued her father’s early nineteenth-century strategy of entrepreneurship by opening dressmaking shops in Philadelphia and Cape May, New Jersey, with her daughter, Mary. Sarah was also something of an early feminist, who insisted on her daughter attending the Institute of Colored Youth so that she could support herself and never be dependent on a man. She taught her daughter to speak her mind forcefully even in the presence of men, and stand up for women’s rights. For example, when Pliny wrote from Tennessee that Governor Brownlee’s daughter talked too much, she chastised him for his biased comments about women. But most important, Sarah taught her daughter that she was a member of “society,” and as such, had a responsibility to cultivate her mind, to restrict her social contacts to people of her “class,” and to act at all times as a model of proper conduct. Pliny picked up that Sarah was not only in a different class from his but also may have been dismissive of him and his courtship of Mary. As he wrote Mary in 1875: “She [Sarah] is one of the few persons in whose sight I wish to appear well yet without a hypocritical pretense of being what I am not—without hiding all my faults and failures. To this feeling I ascribe my utter inability to be perfectly at ease in her society.”13

Washington was a welcome escape from the tensions of his courtship and a politically vibrant city at the center of Reconstruction politics. As John Mercer Langston’s secretary, Pliny attended political meetings, wrote speeches for the future congressional representative from Virginia, and helped Langston lobby for passage of the 1875 Supplementary Civil Rights Bill. Pliny argued strongly for integrated schools in a letter he wrote to Mary in 1872: “I am an earnest advocate of Mixed Schools and also of Social Equality. I feel that the colored people will never be able to rival the whites till, accustomed to mingle with them, they lose that inborn feeling of inferiority and that humbling servility, which so plainly exhibit themselves whenever they come in contact with whites.” He criticized as shortsighted Black schoolteacher opposition to integrated schools on the grounds that integration would mean the loss of their jobs. While Black teachers deserved “great praise,” Pliny responded to Langston’s criticism of segregated schools by noting, “I should not like to be called in to disprove it by citing examples of WELL CONDUCTED negro schools.”14 Pliny disliked Black schools on scientific grounds: they were inefficient, dirty, and poorly disciplined, and as a Black Brahmin, he saw himself as a leader bringing rationality and order to a largely inefficient, and often religiously oriented, educational system. Integrated schools were needed to expose Black teachers and students to modernizing tendencies in education.

Moreover, as a man in an increasingly female profession, Pliny believed Black women were not pushing the kind of manly rights he felt Blacks needed to be equal to Whites. Education, for Pliny, was not simply reading, writing, and arithmetic, but the cutting away of that “inborn feeling of inferiority … in contact with whites” from Black children. Masculinity, patriarchy, and a class-conscious lower-middle-class anger fueled his belief in a pedagogy that would liberate Blacks from the White supremacist notion that they were powerless and worthless. Unfortunately for Pliny and his generation of Black leaders, neither school integration nor Black social and cultural equality would become a reality. The wheedling down of the Civil Rights Bill of 1875 and its nullification by the Supreme Court in 1883 spelled the demise of social equality for the Black elite. Pliny’s generation suffered a collective sense of bitterness and frustration captured in his statement, “Negroes seem to be born to become the footballs of the whites.”15

Inside this nineteenth-century rationalist was a bitter man, who, after graduating at the top of his class at Howard University Law School in 1874, never practiced law because Black lawyers were little called for as Black civil rights were systematically eroded in the 1870s and 1880s. Yet except in moments when his anger boiled out from inside, these obstacles did not shake Pliny’s faith that if an educated Black man competed with the White man on his own level, he would be successful. Indeed, his anger at the “recalcitrant youth” expressed both Pliny’s lack of authority and his conservative middle-class belief in self-help.

After graduation from law school, Pliny could obtain only clerking jobs in Washington. When he lost his job at the Treasury Department in 1876, he struggled on shoestring jobs until he returned to his mother’s house in 1879. He spent a summer looking for work and then on August 20, 1879, Pliny and Mary were secretly married. Upon being reappointed to the Treasury in 1879, Pliny returned to Washington without his new bride. After another firing and a short stint at the Freedmen’s Savings Bank in 1880, Pliny returned to Philadelphia for good to take a teaching position at a Black school in South Chester. Only then, when Pliny had obtained steady employment, did the couple inform their parents of their marriage.

Perry’s account of Pliny’s stewardship of the South Chester School is mistaken in one particular: discipline did not reign supreme after Pliny ejected a surly student from his class. In fact, Pliny was appointed principal of the school a month later because the previous one had resigned and no one else seemed to be able to maintain discipline and authority. Over the next three years, a constant struggle ensued at the school, at which Mary began teaching in 1881.

Dissatisfied with the low pay and difficult working conditions at the South Chester School, Pliny applied for a Post Office clerkship. The Civil Service Law of 1883 required all applicants to take a written exam and undergo a rigorous personal interview, which inquired into their employment background and personal character. Pliny achieved one of the highest scores on the examination, and after the interview he was chosen over several White applicants. His selection was heralded by local and regional Black newspapers as an important achievement for a Black man and a signal that the new Civil Service laws were “democratic” in appointing Pliny to an office no other Black man had served in for more than twenty years.

The Civil Service Law was part of a national reaction by the largely Republican, Anglo-American middle class against the dominance of government jobs by Democratic Party machines, often run by the Irish working class. The Black middle class and the Irish working class had remained enemies after the riots of the 1830s and 1840s, and the Black educated elite had continued to tie its bid for upward mobility to assimilation of upper-class Yankee values. While the Civil Service Law did not help lower-class Blacks get jobs in the city, it did reward those like Pliny, who had excelled at education.

In Washington, Pliny had described the predicament of the educated Black middle class. “How well I can now realize the truth and force of the assertion that ‘cursed is that man who hangs on Princes (Congressmen’s) favors.’ ”16 By rejecting segregation, Pliny and his free-born middle class forfeited the option of developing autonomous Black economic and political power. By alienating themselves from the Black masses, Pliny and his class failed to develop a strong constituency among the lower classes of their race. Pliny remained as “cursed” in Philadelphia as he had been in Washington: when the political climate changed in 1886, he lost his Post Office job and eventually returned to teaching.

Despite its limitations, the Post Office appointment was personally significant for Pliny. He had finally obtained a position of prestige and stable employment in his own community of Philadelphia. Alain Locke was born two years after the Post Office appointment, a sign that the young couple felt they could now provide for a family. Yet even before the Post Office appointment, Pliny was resolute in his belief that the ideology of achievement, which fueled his own education and career, would be successful. As he stated as principal speaker on the January 1, 1883, celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation:

Our present, though possibly not all it should be, still is such to give us cause for rejoicing and making indeed a jubilee of this, our grand national holiday. [For men like Frederick Douglass and John Langston] are writing on the pages of history stern facts and not delusive fancies, refuting in their public and private lives the base and unwarranted assertions that the negro cannot rise.

Vested with rights making us theoretically equal to all other men, we owe it to ourselves to see that we shall become practically so. The wide domains of laws, medicine, commerce, agriculture and all the sciences, present pleasing and inviting fields for energy, perseverance and pluck. To these let us turn our earnest endeavors, making the race which patient under suffering, great in deeds and acts. For years we have furnished the muscle; let us now add to it brains.17

We can only wonder what made this proud, brave, and skeptical Black thinker speak such homilies and portents of progress after witnessing so many examples of continued racism. Perhaps it was part of the Black Victorian ideology that the dire circumstances of survival had to be disguised in order that those following would not give up the struggle.

Mary Hawkins Locke, a proper Victorian lady, realized all the virtues of nineteenth-century true womanhood. Metz T. P. Lochard recalled that her graciousness, intelligence, and charm embellished her poised and reserved demeanor. As a Black woman, Mary Locke inherited a matriarchal tradition that valued both work and financial independence for women. But nineteenth-century middle-class Black women could not escape the pressure to live up to the Victorian ideal to be a lady, refined and cultured with a knowledge of art and literature, and respectable—which meant to marry, to have a beautiful home, and to give birth to a son. Mary delayed getting married until she was twenty-nine and settling down to a two-career marriage with Pliny until 1884, when he began to earn a salary from his Post Office appointment. She left her teaching position at the end of the school year in 1884 to become a full-time housewife. Little more than a year later she gave birth to her first son, Alain LeRoy Locke.

The marriage and family life Mary led was far different from what she expected when Roy was born. After Pliny was dismissed from his Post Office job, Mary, who had spent the first year at home nursing her sickly son, had to return to teaching. She was able to secure reappointment at her old school in Camden. During a family discussion, Pliny made a remarkable suggestion: he would take a janitorial job so he could work nights and care for their son during the day while she worked. The adult Alain Locke recalled this as an important factor in his childhood.

Although I was idolized by both parents, early childhood life was unusually close with my father, who changed his position from day to night shift in the post-office to be able to take care of me. This included bathing and all intimate care since father was distrustful of the old-fashioned ways of both grandmothers. He became my constant companion and playmate, though forced to resume daytime work when I was four.18

Locke wanted to hide that his father was a janitor, but he liked the devotion expressed by an ambitious father willing to change his work to care for his son.

Mary resented having to give up her close relationship with Roy in order to work. She was angry that she could not depend on Pliny for regular employment and that he did not take respectable work, such as a teaching job. She also resented his implicit criticism of her mother’s child-rearing. Most important, she resented his displacing her as the most important person in Roy’s life. As Locke recalled:

Relations with mother were also close in spite of this unusual interest on the part of the father. This was not only due to their common fixation on their “one and only,” but on the fact that our physician prolonged lactation by special diet so that I nursed at the breast until the age of three, and after weaning had to be fed milk by the spoonful. I would take it in no other way and it had to be whipped into bubbles; presumably because of being used to the aeration in breat [sic] feeding.19

While working, Mary returned from school twice a day to feed her son. Mary did not need much encouragement to continue breast feeding. Both parents fought for the attention of their child, which increased his initial feeling of being “adored by both parents,” but also sowed tension. This young but already sensitive child felt the building conflict between the parents. “Both parents were extremely strong-willed personalities and knew not to cross one another.”20

Locke would only be weaned after his mother gave birth to another son in 1889. After Pliny took over Roy’s childcare, he potty-trained his son at the age of two. He taught him to organize his clothes, to wash, to take care of some of his own needs, and to take responsibility for informing his father when he needed attention.

Pliny did not want to give over his son’s nurture to women, not even his wife. He did not want a spoiled son, a quality he already saw developing when he took over home care from Mary in 1886. He instructed Roy in self-sufficiency, explaining to the boy that his mother could not be with him because she had to work. Pliny taught Roy to read by reading aloud to him such classics as Virgil’s Aeneid and Homer’s Ulysses in the afternoons after the boy’s early morning math exercises were concluded. Young Locke learned early that intellectual brilliance pleased both parents, but especially his father. By age four, he was already serious, so unconcerned with humor and frivolity that he later recalled that, when given the task of going downstairs on Sunday mornings to retrieve the paper, he first cut out the comics section before bringing it upstairs.21

Locke gives us the flavor of this boyhood:

I was indulgently but intelligently treated. As an example, bed time routine was a ritual, my father first, this included an inspection of my clothes which had to be arranged orderly on a chair by the bedside: father intended a military school for my early boyhood training, and then my mother. No special indulgence as to sentiment; very little kissing, little or no fairy stories, no frightening talk or games. The housekeeper was dismissed by my father for frightening me by tales og [sic] the “Boogy-man.”22

Pliny was a rationalist who believed that superstition, and indeed religion, had no place in the instruction of children. As Locke recalled, “I was unusually obedient, but never had any unreasonable conditions to put up with, since most things were explained to me beforehand.”23 Son and father took walks in the park near their home, his father explaining to him the various trees and foliage and the rudiments of botany. His father wanted him to become a doctor, but after discussion with his mother about the boy’s weak health, it was agreed that he would be a teacher.

The effect of this upbringing was that Locke developed his ability for logical analysis, but generally lacked feeling. In his own recollection: “I was a self-centered, rather selfish and extremely poised child, mature enough even before my father’s death to be indifferent to others and what they did or thought. I would not accept money or gifts from other people, no matter how tempting. Was trained to be extremely polite but standoffish with others.” Of course, this social distance was not simply the father’s doing. His mother, father, and grandmothers reinforced this atmosphere of severe restraint:

I must have at one time, but I have no memory of having slept in anything but my own room, and scarcely have any memory of seeing any of the household undressed. Though a relatively poor family, household etiquette was extreme. Except while being bathed I have also no memory of ever being in the bathroom with anyone in the family. It was a household where we washed interminably, and except to keep from open offense to others, I was taught to avoid kissing or being kissed by outsiders. If it happened, I would as soon as possible without being observed, find an excuse for using my handkerchief, often spitting surreptitiously into it if kissed too openly.24

The Locke family’s phobia of contact with undesirables crystallized within the family into racial self-hate. Locke recalled that his maternal grandmother, Sarah Shorter, would rise early in the morning to wash the family clothes and then hang them to dry before the neighbors were up. In addition, when he was instructed to help her with the laundry, she chastised him from under her large floppy hat and gloves to “Stay out of the sun! You’re black enough already!” Through the education of his family, Locke learned that he must do everything possible not to act Black, to deny who and what he was. Pliny’s attempt to limit the influence of the grandmothers becomes understandable as an attempt to shield his son from their negative social conditioning. Pliny obsessed over cleanliness as well. Constant cleaning, bathing, and avoidance of the sun were compulsive if unsuccessful strategies to wash off the stain of Blackness and deny that being Black meant the family could never live the life of White “Proper Philadelphians,” whose manners, homes, and aspirations the Lockes emulated so closely.

Denial also characterized Alain’s response to the birth of his brother in April 1889. He never publicly acknowledged the birth of Arthur Locke (apparently his parents changed our Alain’s name to Alan or Allen prior to this Arthur’s birth; later Locke himself changed it back to Alain). In only one autobiographical reference did he admit to having a brother; in others he claimed to be his parents’ “one and only,” arguing that because of “the necessity of a double salary to maintain a decent standard of living, they had agreed on only one child, if the child was male.”25 Clearly the existence of a rival to his mother and father’s affections was too much for Locke to bear. When Mary had to nurse this second sickly child and could no longer nurse her firstborn, Alain refused to eat for days until his frantic father discovered that whipping the milk persuaded his son to drink it. Even in a household with two grandmothers, a precocious, jealous three-year-old was too much to handle. Arthur Locke died six months after his birth.

Shortly after Arthur’s death, Pliny was able to resume his full-time nurture of Alain. But around the age of four, Alain began to resist the father’s overtures. Pliny sought to mold his son in his own image, and being a lieutenant in the National Guard, he wished his son to attend military school. Pliny was a skilled baseball player on one of the local Colored Baseball League teams, and one afternoon in the backyard of their new residence at 1574 South 6th Street, Pliny tried to teach his son to play catch. After several refusals by the younger Locke to cooperate, the frustrated father wound up his arm and threw the baseball at Alain, who protectively wrapped his arms around his body. Locke later recalled that even at this early age, he possessed a clear sense of those activities that suited him and those that did not; masculine sports such as baseball were not his idea of recreation, and this strong-willed son would have nothing to do with it.

Pliny began to realize that he was losing the battle for his son’s gender identity. He noticed that when Mary was home over the summer, Alain spent most of his time clinging constantly to his mother’s skirts and legs and, even if rather unhelpfully, joined in his mother’s “feminine” activities such as sewing, making hats, and creating the decorative lace things with which she and her mother beautified their relatively modest home. Locke was not going to grow into the aggressively masculine “ladies’ man” that Pliny had styled himself in Washington, and the father, obsessed with creating his child in his own image, was unable to allow the child his own identity.

The increasing tension between father and son culminated in Pliny whipping Roy for some unrecalled infraction.

When during one of mother’s absences he chastised me with the only whipping I remember ever having had; my grandmothers were strictly forbidden to discipline me (and I knew that, much to their chagrin) it was then decided (when I was somewhere between four and five) that mother was to have final authority in discipline. I either remember or was told that this was one of the few serious quarrels of their married life, and that it had been settled that way on mother’s ultimatum. Both were extremely strong-willed personalities and knew not to cross one another. Both were bread[-]winners and therefore relatively independent.26

At the time of this incident, Mary’s teaching job paid considerably more than Pliny’s janitorial job. She possessed both the economic and psychological leverage to leave the relationship if Pliny did not sacrifice his authority with the child. Pliny’s beating of Alain was a continuation of his attempt to control his increasingly independent son. The father vented his mounting rage at the boy for his emerging effeminacy and his bent toward the aesthetic pursuits of the mother.

Alain was already a spoiled child who let his grandmothers know, through his disrespect of their commands, that he realized they could not spank him and therefore had no real authority over him. Now Pliny lacked that authority as well. Pliny could now only propose, suggest, entreat his son; he could no longer command. As laudable as was his mother’s desire to protect her son, Locke recalled his mother protectively placing her arms around him to shield him from his angry father—her act also served the selfish motive of reestablishing her primacy in her son’s life.27 Her love was greater because she would not punish him, would not limit his indulgence, and would continue to spoil him rather than rein him in.

The mother’s victory made Alain identify with his mother as the power center of the family. Even more than before, he copied what she did, how she walked, how she talked, and how she viewed the world in order to acquire by imitation the power she had. He would take her side and saw the negative aspects of the family’s economic situation as his father’s fault. “If only he had … ” complained the mother, and he picked up the tune: “If my daddy had done what he was supposed to do.”28 He sided with her because she was his protector, and even as a mature man, Alain would be drawn to and mimic the ideas of older women who served as protectors and patrons in his adult struggles against patriarchal authority. This dialogue between mother and son took place behind closed doors. An adult Locke simply refrained from mentioning his father. Locke did resent his father for not being a recognized leader, serving as a secretary to a celebrity like John Mercer Langston, rather than being an outstanding lawyer and statesman himself. Like his mother, Alain Locke wanted to be respectable, and that required superlative ancestors.

But the real source of Locke’s reticence about his father before outsiders may have been rooted in the white-hot rage he felt for his father after the beating. Did not his father claim to rule by reason and not force? Had Roy not been an obedient child who, once things were explained to him, did what he was asked? How could his father, whom he idolized and loved for his strength of character and moral rationality, commit this immoral act? Afterward the son felt the arbitrariness of all moralism, that there was no just God, just simply the rule of force and power. The incident also planted deep within him a hatred of patriarchy and the kind of power Black fathers wielded over their families.

Locke sensed, but was too young to really know, that he was spanked for being different. He learned early not to reveal himself to others, to cloak his vulnerable identity so that others would not be able to punish him similarly. Locke would be teased and tormented by both Black and White schoolboys of Philadelphia. From the Whites, the harassment would leave him confused as to whether his race, his size, or his effeminacy were the cause of his being singled out for abuse. With the Black boys it would always be clearer: in him even small Black boys found someone against whom they could prove their marginal manhood with little fear of retaliation. The effeminacy, moreover, in a Black male context legitimated the violence: why not torture the little Black faggot who dared not to be masculine?

After the beating and his mother’s ultimatum, Alain avoided contact with his father, especially in situations where the two were alone. That distance was made easier by Pliny’s decision to return to daytime work: Pliny obtained a teaching position when a school for Blacks opened in Thurlow, Pennsylvania, in July 1890. Then, in 1891, Pliny competed for and won the post of meter inspector in the gas department, the first Black man to secure such a Custom House appointment in Philadelphia, the Black press crowed. During the first year, he did not draw a salary, but by 1892 he was appointed inspector in the gas department. Unfortunately, just at the point when Pliny was regaining his prestige in the family through professional accomplishment, he developed heart trouble and died on August 23, 1892.

Pliny’s death came less than three weeks before Alain’s seventh birthday, at a time when the child saw it as a victory in his rivalry for the mother. She had already shown that her loyalty was to her son and not to her husband. From the child’s standpoint the spanking symbolized the father’s desire to kill him; now the father had died from the blow he delivered in return.

The death freed Alain from an oppressive father but saddled him with a new burden: defining an identity separate from his mother. That task would prove more difficult for Locke:

Of course, my father’s death at six, threw me into the closest companionship with my mother, which remained, except for the separation of three years at college and four years abroad, close until her death at 71, when I was thirty six. I returned home during every vacation and when abroad my mother visited me every vacation. As a child I stopped play promptly and waited for her return every school day, and the only childhood terror I vividly remember, was about [an] accident that might have happened to her, if by chance she was late.29

He could live without his father, but not his mother for the next thirty-seven years.

His father’s death also left Locke free to pursue his mother’s interest in the aesthetic realm. Had his father lived, Alain Locke might have been pressured to pursue the scientific and rationalistic careers of medicine, law, or mathematics, but now he could immerse himself without restriction into the decorative arts, religious mysticism, and sentimental literature. As a young adolescent intellectual, he would extol the values of the Victorian society his mother lived in and represent himself as a custodian of that culture. But underneath his appearance of “respectability” was an aesthete and a dandy who rebelled against “responsible” society as a literary decadent, bohemian, and homosexual. Here were the beginnings of his rebellion against his mother’s authority in his subversion of the bourgeois sentimental values she extolled. The rebellious rogue of the father lived on, inverted into the outrageous dandy barely hidden in the figure of the son.

Most important, the father lived on in Locke’s later approach to race politics. The father’s death removed the political temper from the family, and for the next sixteen years, not only was Locke’s primary interest in aesthetics but he also actively avoided involvement in racial politics. Aesthetics would become an escape from the Black experience and the responsibility of race leadership. Only after returning from Oxford would Locke begin a career as a lecturer on race topics.

Pliny Locke’s funeral took place on an oppressively humid day in August, and while reported in the Black press, it was a small affair attended by thirty of Philadelphia’s Black elite and a smattering of Whites. William Armstead, an early suitor of Mary’s before her marriage to Pliny, may have helped the widow as she walked from the burial site. Back home, Mary probably closed off the upstairs bedroom where her husband had died, as was the custom of the time, and returned downstairs to prepare her son’s special diet of eggs and celery.

Alain was all she had left to live for and, while her mother still lived with them, Mary’s attention was focused on providing him with the support and encouragement needed to make it without a father. The next morning, she arose earlier than usual to paste up in the kitchen a phrase she had written down at the last Philadelphia Negro Improvement Association meeting: “Aim at the sky if you want to hit a tree.” Fifteen years later, on the evening of his Rhodes Scholar appointment, Locke would recall this injunction to high achievement as being an instigator of his early ambition to be a success. It was a sign to this young boy that he was now the hero in this female-dominated family and that he must live up to his mother’s cultural expectations.

His father was gone.

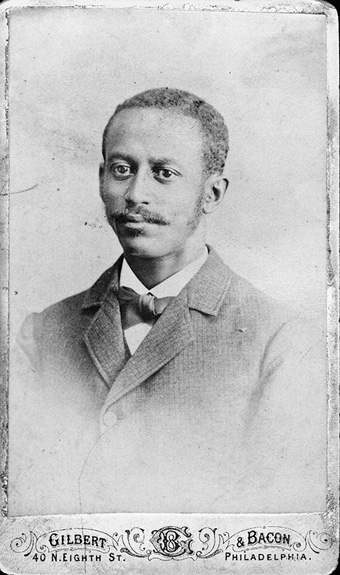

Pliny Locke, September 10, 1875. Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.