13

Race Cosmopolitan Comes Home, 1911–1912

Coming back to the United States in the fall of 1911, Locke was welcomed by Black America despite his having been away so long. Since he had been gone, the NAACP had emerged and W. E. B. Du Bois’s Crisis had captured the imagination of educated African Americans. Booker T. Washington was still the most powerful Negro in America, but his star had dimmed after Taft won the White House in 1908 and reduced Washington’s influence over federal appointments in the South. In the shadow of contested Negro leadership, a new diversity of opinion had emerged among Black political voices that made the African American intellectual climate open to Locke’s unique perspective on race. Perhaps closest to Locke’s views were those of older, African American thinkers who were nationalist in philosophy, but conservative in personal style and political action, men like John Bruce of New York and John Cromwell of Washington who served as custodians of culture in the Black community. They used their influence to raise the quality of debate among the African American bourgeoisie in emergent literary and historical societies that featured lectures on politics and history, poetry readings, and music and art exhibitions. When he returned to Philadelphia, Locke found that men in these societies were eager to provide him an opportunity to announce himself as a new voice in African American discourse. Not long after he settled in at 579 Stevens Street in Camden with his mother, Locke was heading out on the speaking circuit.

The American Negro Historical Society in Philadelphia invited him to speak on October 24, and William C. Bolivar, a family friend and contributor to the Philadelphia Tribune, had probably alerted fellow society members that Locke was back in the Philadelphia area. Bolivar may have brought Locke to the attention of Levi Coppin of the Baltimore Bethel AME Church, where he spoke on November 2. Coppin was married to Fanny Jackson Coppin, formerly the head of the Institute of Colored Youth in Philadelphia that had educated both Pliny and Mary Locke. Alain’s parental network came alive. Locke coupled the trip to Baltimore with a trip to Washington, where he spoke at Howard University and was introduced to Washington society by Roscoe Conkling Bruce, superintendent of Washington’s Black schools. Locke seems to have made a great impression. Locke wrote his mother:

Having veritable ovation. Young Bruce gave smoker last night—all the younger men & Judge Terrel[l were there]. Have seen all old-timers including Mrs. Langston. Too much news to tell—had fun at Howard. Don’t worry, keeping up though very tired. To speak possibly before Bethel Literary in Washington ten days or so … also speak before Negro Historical of New York if time permits. Crummel is arranging this and proposes me next meeting for election to the Negro Academy.1

Although Locke had done everything he could to remain in Europe, he was actually happier and more energetic in America, a train ride away from his mother, but also speaking to a Black patriarchal audience that embodied the energy and activism of his father. He was also giving talks to people who actually wanted to hear him, looked up to him, and celebrated him as one of their own. Only Black people in America would praise him for having “brought such distinction to the race,” as Rev. Levin Coppin put it, and such praise buoyed Locke’s spirits and reaffirmed that he was somebody special. Throughout his life, Locke acted as if he did not need such confirmation, but he did, especially now.

Locke was especially pleased by how the elders of the race embraced him and his standard speech for 1911, “The Negro and a Race Tradition,” where he argued Black intellectuals must see themselves in terms of race. This message played well in these historical societies, and Locke made sure he linked it to praise of the elders, such men as the late president of the Philadelphia Historical Society, Mr. Adjer, who had, as Locke put it, stood for tradition “persistently, effectively, quietly, unassumingly—almost silently.” Ironically, the man most alienated from his father was quite comfortable praising the tradition of Black patriarchy to introduce himself to the Black community. But that rhetorical maneuver was the set-up for the Oedipal Locke to emerge and reveal his real message—his critique of the “antiquarian” tradition that Adjer and others had institutionalized in these societies, the “tradition of personalities, incidents, a tradition of records, but records that were at the same time souvenirs.” In 1911, the Negro needed a different kind of tradition, of “racial-consciousness rather than race-memory, of race culture as distinguished from but not opposed to race history.” As a kind of Promethean coming to them from Oxford, Berlin, and the Universal Races Congress in London, Locke brought the new knowledge of a scientific rather than the hagiographic story of individual Black successes. Negro historical societies needed to break with their provincial past and begin to think about the predicament of the Negro in comparative terms. “Our problems in the matter of history,” Locke noted, “have their analogies for the average American, for the American’s broken past we have a forgotten past, in place of his voluntary revolution we have involuntary transplantation.”2 Most Negro historical societies avoided the discussion of slavery—the great “transplantation”—because it embarrassed them. But Locke argued Negro Americans could not hide from the pain of slavery and worsening contemporary race relations by perpetuating a sanitized history.

Locke even skewered Du Bois to drive home his point that the Negro intellectual had to be relentless in thinking in terms of a Negro intellectual tradition. In a revised version of the lecture Locke delivered to the Yonkers Negro Society for Historical Research in New York on December 12, Locke critiqued that line in Du Bois that gave the illusion that in the realm of culture the Negro intellectual was a peer.

Few indeed are those of us who have escaped entirely the subtle seduction of this illusion, all of us at certain times or in certain moods are its victims. I think of the momentary lapse of an almost irreproachable scholar who was tempted into the rare boast that he joined hands with Shakespeare & Plato above the color line[.] Was he anything less of a Negro in Shakespeare’s world or in Plato’s presence? Intellectual affiliations may be a philosopher’s solace for denied opportunities; and dead poets may be more friendly & sociable than living ones—they should be certainly to the scholar, but what a warped sense of personal identity it displays to associate the Negro personality with these pains & the disembodied self with the pleasures & compensations of life. Not that one need think [badly] of the situations which may make Plato & Shakespeare mental refuge from physical pangs and social disgusts, but that one track the error and review the issue inducing in the minds of the best informed and most valuable of the race the dilemma of conflicting loyalties and the pangs of a divided consciousness.3

Locke was feeling quite cocky up in New York to crack on Du Bois’s fantasy of transcultural communion above the color line. But after his experience at Oxford, Locke could not read the lines in Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk and not gag.

I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil.4

Certainly, the “great men” of Oxford had “winced” in Locke’s presence, had not treated him “graciously” but with “scorn” and “condescension.” Culture could not wash away the racism endemic to knowledge dissemination in the West and the Negro could not “glide” across centuries without race dogging one’s tracks. “From the fact of being a Negro there is no escape—no, not even in education and culture,” Locke went on. “No individual or group can break loose from its ethnic tradition without landing ultimately in an historical dilemma.”5 Before these historical societies, Locke was returning from his educational odyssey to tell his listeners the “Truth”—that educational elites never forgot that one was Black. The good news was the silver lining that exclusion created agency—to build one’s own stately mansions, one’s own tradition of excellence in reason and art in the world of culture.

After his Yonkers lecture, the members of the Historical Society hailed him, especially John Bruce and Arthur Schomburg, the founders of the society. As Bruce wrote to Cromwell, who had recommended Locke as a speaker to Bruce:

Well, Locke came over and gave us a splendid talk. We kept him all of Saturday night and all day Sunday and part of Sunday night and parted with him with some reluctance. He is a worthy son of a worthy sire. I remember his father. Everybody here who met the son is pleased with him. My! but he is a mite of a chap, but “he had a mighty intellect and talking ways.” I liked him much and felt that I had always known him. Mrs. Bruce was “carried away with him but she has returned.” … I tried to give him a decent press notice in the local papers … and a fair resume of his paper which was a thoughtful and scholarly effort.6

Locke had won over his hosts because of his father, because of his excellent bearing and manners, and because he was able to present himself as the new Black voice. As he wrote his mother, “I was hailed all around, bravo, better than Du Bois, etc.”7

The problem was that Locke had not completely accepted the lesson he shared with his listeners in “The Negro and a Race Tradition.” While characterizing Du Bois as naive, Locke himself was still dreaming. At the very moment Locke was lecturing American Black intellectuals about the benefits of sticking to one’s own traditions, he was busy as ever trying to break free of them, still regarding elite White Americans and Europeans as the really high-minded people of culture, and still dreaming of spending his next two years in a comparative race study travel scheme that would in effect allow him to hobnob with White people in Europe, not Black people in America. His cynicism was not confined to Du Bois, for as Locke wrote his mother about his lecture, “all you have to do is to tell Negroes how much you love them and they will sing your praises to the high heavens.”8

Of course, Locke would hardly have impressed John E. Bruce, the Black journalist and racial nationalist if he had argued, as was possible, that as a Europeanized Black intellectual he still suffered from the kind of “double consciousness” he critiqued in Du Bois and that, in fact, Locke saw that double consciousness as a strength rather than a weakness. Bruce, who worked as a clerk in the State of New York’s Treasurer’s Office, epitomized the kind of race consciousness Locke described in his lecture: he was a politically savvy Black Republican who believed self-organization if not self-segregation was the only salvation for Black people in America. Bruce’s racialism did have its pathological aspects—the dark-skinned Bruce was extremely color-conscious. In a letter to John Cromwell, Bruce wrote that after hearing Kelly Miller lecture forcefully in New York, “I’m glad that he isn’t yaller.”9 Such prejudice did not stint Bruce’s praise of the light-skinned Du Bois, however. But what endeared Bruce to “The Negro and a Race Tradition” was that a young African American could go to Oxford and Berlin and come back to America to recommend Black consciousness as the road forward. To do that required Locke to hide the complexity of the man that education had actually created in him.

Locke was not only performing race, but also masculinity. This “mite of a man” continued, in Bruce’s eyes, the tradition of outspoken Black masculine leadership that the post-Reconstruction generation was known for. That Locke could appear as fierce and manly a leader as his own father, and be culturally more sophisticated boded well for men like Bruce, hoping that the next generation would carry over the virtues of his. Locke viewed Bruce as a kind of sympathetic uncle, someone who though mired in the old tradition, supported the cultural approach to race that was the subtext of Locke’s “Race Tradition.” Locke showed he was already adept at managing the generational struggle between himself and the older generation of Black intellectuals by presenting himself as their heir and not a threat to their leadership.

When Locke left Bruce’s residence at Sunnyslope Farm in Yonkers that December, he gave the impression, ironically, that he would be returning shortly to Berlin. Interestingly, the path to a Black tradition lay through the Teutonic Empire. His listeners knew he was a thoroughly Europhile Negro, but they accepted him nevertheless, because he seemed to be on a mission for them, one that would carry him back to Europe to take another of its intellectual prizes. But Locke was so deeply in debt and his lectures netted him so little he had no choice but to remain in America. On January 1, 1912, alumni of his high school entertained Locke in Philadelphia, and on February 15, he was back in Washington, D.C., giving a lecture to local teachers. This was arranged by Cromwell, who seemed to take a personal interest in trying to get Locke established in the capital. The lecture brought him $25, considerably more than the usual $10 he received from the historical societies, and it gave Locke a chance to hobnob with the Washington elite. “I am returning tonight,” Locke wrote his mother on February 17, “although invited to stay over and of all things to go to the Assembly with W.H. Lewis. Dined with Lewis last night. Lunch with him to day. Speech a success, delivered two others since. Bruce matter pending and somewhat doubtful.”10 Lewis was a graduate of Harvard, a lawyer, and a prominent lieutenant of Booker T. Washington. So was Bruce, who had led Locke to believe there might be a place for him in the District of Columbia school system, which never materialized. But Locke did not want to become a public school-teacher, at least not yet, not until all other possibilities, especially the possibility of returning to Europe, were exhausted.

Indeed, John E. Bruce was surprised to learn from Cromwell early in February 1912 that Locke was still in the United States. Bruce was pleased, however, since “I may yet get another chance to meet him before he leaves these shores. Remember Mrs. Bruce and myself to him most kindly and say that we are looking forward to seeing him at Sunnyslope ere he says farewell to America.”11 Bruce was probably surprised as well when he learned early in March through the grapevine that Locke was to accompany Booker T. Washington on a trip through the South. Bruce did not like Washington and considered him a toady to the White people. Indeed, Locke’s lecture had prompted Bruce to write Cromwell that “I could not help thinking what a Jonah Booker Washington is to the race, and what a mistake his propaganda is. Alain Le Roy Locke was born to scholarship. He’d never make either a good gardener or a good shoemaker and there are thousand[s] of our boys scattered all over this country who like him only want freedom for their wings.”12 While at Sunnyslope, Locke had not let on to Bruce that he was friendly with Washington, and most of his African American patrons did not know until he had left on this trip that such was the case. During the first week of January, Locke would meet Washington in Philadelphia and assist the Wizard in meeting his train south to Tuskegee.13

While Bruce and Cromwell were helpful in obtaining speaking engagements at African American historical societies, only a man of Booker T. Washington’s stature could bring Locke’s name to the attention of the White intellectual establishment. That was Locke’s main goal at the beginning of 1912. He wanted to make another run at the Albert Kahn Travelling Fellowship, and he needed heavyweight influence. As Locke had learned, Washington was reluctant to put his influence behind someone he did not know well. Locke needed time with the Wizard to build some rapport, and that opportunity came in late February when Dr. S. G. Elbert of Wilmington, Delaware, withdrew from a trip through Florida organized by Washington. This was one of his annual trips through the South, on which Washington stopped at numerous small localities and made speeches designed to secure White finances for his education projects and build popular support among the Black southern community for his policies. Locke jumped at the opportunity to observe the Wizard at work. Washington seemed pleased as well, writing Elbert on February 26 that he was “glad to have Mr. Locke take your place[;] he will have no expense at all during the trip through Florida and only his expense to florida [sic] and return after tour is complete[;] tour begins at pensacola [Florida] march first.”14 Washington’s reference to Locke’s expenses was designed to allay Elbert’s concern that Locke would not have enough money to make the trip. Elbert still insisted on Locke coming down to Wilmington for dinner and a conference before catching the train to Pensacola. Unfortunately, Locke missed the train that would have given him enough time to dine with the Elberts. When he arrived at the Wilmington station with only a half hour to spare, Mr. Elbert came down to the station and attempted to press a roll of “bills, I don’t know how many” into Locke’s hands, stating that he could borrow for the trip if he desired. Locke respectfully declined, although he promised to wire Elbert if he did run short during the trip. For Locke it was good to know that finally he was encountering some sympathetic Whites who could help him financially.

Elbert’s offer was appreciated, because Locke felt considerable uncertainty about what lay ahead of him on his maiden voyage south. Since Washington would not be boarding until Montgomery, Alabama, Locke started his first trip through the South alone. The trip went well, however. He was not Jim Crowed in his riding car before reaching Alabama, although he could not eat in the Pullman car. Instead, his meals were “served on a Pullman table put up at my seat. How much trouble they go to save their old prejudice,” he casually informed his mother. While writing her from the observation car as the train traversed Georgia, Locke noted, “as I write this an old confederate opposite sits & glares. I guess it makes him angry that I can write.” Generally, though, Locke was able to concentrate on what he had really wanted to see, the South. “The trip is beautiful—but what a poverty stricken land white & black. I am observing closely for journalistic material.”15 The pace quickened after Washington and his party boarded. They made their first stop on March 1 in Pensacola, and the Pensacola Journal on March 2, 1912, documented the Wizard in action. “Dr. Washington … gained the sympathy of both races immediately in his audience by asking the negroes present to sing a few of the old-time plantation songs.” Washington cooed White southerners with the sounds of slavery, reassuring them his Negroes were no threat to White supremacy. More concretely, “sensible advice was given to the negroes with reference to dependability to labor, with reference to idleness and crime, and on the other hand the white man’s responsibility in the direction of negro education and progress was emphasized.” By voicing Henry Grady’s New South paternalism, Washington hoped to foster White support for Negro education by claiming it would make Blacks better laborers. But the people standing on stage with Washington were not day laborers, but prominent Black individuals in business, education, and the church: “J.C. Napier … Chairman of the executive Board of the National Negro Business League; M.W. Gilbert, president Selma University … Bishop G.W. Clinton, A.M.E. Zion Church … George C. Hall, physician and surgeon, Chicago, Ill. Alain Le Roy Locke, Rhodes Oxford Scholarship Student.”16

Locke wrote his mother that, except for Washington and Emmett Scott, Washington’s second-in-command at Tuskegee, he was the star attraction. Locke’s claim was supported by the enthusiastic applause of the Black audience that greeted him at Pensacola. Such a welcome also supports historian Richard Potter’s contention that the Black people in the audience understood that the spirituals and Washington’s rhetoric were intended to camouflage an opportunity to celebrate Black achievement. Still, Washington felt that even this delicate balance had to be adjusted as the party traveled southward. After the Pensacola reception, “W[ashington] questioned the advisability of mentioning the Oxford University scholarship affair farther south in Florida, where feeling is more adverse. Mr. Napier did the stunt and is of the uncompromising sort to repeat it.” Locke seemed to react as if he had been taken down a peg, for he continued, “I shall see that he does and have something to say on the question to B.T.W. at the end of the tour.”17 Locke’s name actually disappeared from the record of the next stop at Ocala, but he was listed as speaking on “schools and scholarship” at Lakeland, Florida. Washington was right about the “more adverse” feeling farther south. For the day that the party reached Jacksonville, the town was hysterical over the capture that same day of five African Americans accused of murdering a local shopkeeper and assaulting his wife and two children. “Wild were the scenes enacted last night,” reported the Florida Times-Union:

A mob consisting of several hundred men, women and youths gathered at the corner of Forsyth and Ocean streets, and from there proceeded toward the police station. There a squad of policemen, with drawn clubs, held the crowd at bay, but after several ineffectual rushes they were finally dispersed with a stream of water directed at them by men from the central fire station.18

The crowd, however, was not confined to the jail. As Locke informed his concerned mother, “You will have seen by the papers that a lynching was narrowly averted here—we could hear the mob howling while Dr. Washington was speaking—the party were [sic] conducted under police escort safely home—Dr. Washington slipping out while they were singing. It was brave of him to continue his speech at all.” Not surprisingly, Washington’s speech was not reported in the Florida Times-Union, as both headlines and secondary stories detailed how effective sheriffs had been in capturing the alleged perpetrators and preventing a lynching. Such coverage was responsible at least in that it reassured an outraged community that justice was swift and mob action unnecessary. But it also showed how irrelevant Washington’s message had become. As James Weldon Johnson recalled in his autobiography, Along This Way, Jacksonville was no longer the city of harmonious race relations it had been during his childhood, because the White populace had changed: it had rejected the paternalistic ideology of Henry Grady and adopted the turn-of-century view that the Negro was a beast that had to be kept down, and failing that, killed. It was wise Washington skipped out.

Writing two days after the near riot, Locke put the best face on the situation. “Yesterday things quieted down and we had the day of the trip visiting the schools and business enterprises of Jacksonville.” But some members of the party had seen enough by Thursday. One was J. C. Napier, who “wanted me to go to Nashville with him and I was going, but he left suddenly night before last when the mob broke out.”19 Despite his calm reassurance to his mother, Locke himself had been shaken by this display of naked White power. One of the members of the group remembered in an interview that Locke cowered in the man’s arms as the party was whisked away with the crowd yelling outside. This nurturing fellow could not understand what frightened Locke so much. Of course, Locke was not above using such a situation to ferret his way into a man’s arms. But Locke had stumbled into a situation that really rankled his nerves. Earlier on the way to Montgomery, he had joked in a letter to his mother that he would finish an essay he was writing on lynching when he returned to Philadelphia, “if I am not lynched myself.” Suddenly, he had come face to face with the reality of southern murderous violence; and he had reacted with all the pent-up fear he had carried within himself from the moment he had “crossed the line” into the South.

That incident left a mark on Locke’s mind. Regardless of the wonderful subsequent receptions for him as he completed his southern tour, something in him resolved not to take a job in the South if he could at all help it. True, he was lionized at Jacksonville the next day, once the threat of a lynching had passed, and Jacksonville’s thriving Black business and academic community had properly welcomed him. Arriving at Tuskegee, he received the kind of introduction accorded a returning military hero. “The whole school paraded yesterday in my honour and I walked inspection up and down the lines with the Captain in charge. Last evening I made my second address to the school, quite a good speech—I had been invited to two faculty meetings and had addressed them—also the men’s club gave me a smoker and supper and the boys of the Glee Club serenaded outside.” Yet Locke could not dispense with his cynicism even at this moment of southern Black community embrace. “It pays to tell Negroes I am of you with you and for you. Three cheers for the Negro,” he concluded to his mother.20 His real reason for visiting Tuskegee was not to consider joining its faculty, but to have a personal conference with Emmett J. Scott at which the two of them would draft “Booker’s letter of endorsement” for the Kahn Fellowship. Upon leaving Tuskegee on March 19, Locke proceeded to Atlanta Baptist College (later known as Atlanta University), where he enjoyed a personal conference and tour of the facilities with John Hope, its president. Locke liked what he saw of the campus and the faculty, but could not help recalling that just six years before the town had erupted in one of the worst race riots in southern history and forced Du Bois out of the South and academia and into work for the NAACP. Perhaps the only place of significance Locke did not visit was Fisk University, but Mr. Napier’s flight had precluded that. For all of its educational development, the South still represented for Locke a step back into the Dark Ages.

Perhaps the most humorous interchange of the trip occurred between Locke and Carl Diton, his former Central High classmate, who was music director at Payne College in Augusta, Georgia. Locke wrote to Diton from Jacksonville to find out if he could get any paid speaking engagements at Diton’s college. Diton was at first shocked that Locke had written him, since after his graduation, Locke had always discouraged Diton’s attempts to establish a correspondence, let alone a friendship. When Diton had tried to contact Locke when he went to Germany in 1911 to study music, Locke had kept Diton from knowing his whereabouts. Now in the South and near destitute, Locke needed his “old friend” Diton, but he was not fooled. “Your letter of the 9th,” he wrote, “came rather as a surprise to me for I was thinking that you had about arrived in Europe. … Knowing the calibre of your works I should deem it unwise to present you or have you presented here—that is, unless you have changed your style of expression from that which you use when talking before our historical societies. I am much afraid that these folks would be apt to miss the point.” Of course, “if your ‘hard luck’ tale is really true, why I think that I can scare up a crowd of a hundred and fifty—or two to hear you talk at ten cents a piece. Probably you’ll realize ten, fifteen or twenty dollars therefrom. But don’t count upon it.”21 Later, when it was clear Locke was not coming, Diton quipped, “I think you are making a mistake in not seeing Fisk. What’s your hurry? You’ve been going to Europe since November. Why not put it off some days later and take a faster steamer?”22 Once again, Locke was using Europe as an excuse, but his real hurry was to get to New York for conferences with Booker T. Washington and the trustees of the Kahn Fellowship. His exchange with Diton showed, however, that Locke needed to repair bridges with former friends and Black intellectuals whom he needed if he wanted to become a Black leader of influence in the United States.

Hurrying north, Locke arrived in New York on April 11 and, using the Hotel Marshall at 127 W. 53th Street as his base of operations, began his campaign for the Kahn Travelling Fellowship he needed to fund his travel-research trip through Europe and Africa. Having won late admission to this year’s competition, Locke wanted to build support among the trustees for his project. At first it was hard to get appointments, but once Washington’s letter to Nicholas Murray had arrived, Locke met with several officials, including the chief commissioner of the fund. His New York stay also allowed him to connect with significant Black intellectuals and artists. He dined with Du Bois on April 14, met the emerging young Black artist, Lonsdale Brown, and returned to Bruce’s Sunnyslope farm. Unfortunately, all of Locke’s efforts were for naught. As he informed Washington on May 20, the Kahn committee turned him down. The project was very expensive (around $5,000) and would have involved allowing Locke to sell articles from the research trip to various newspapers, which may have reduced its value in the eyes of the trustees. Race, of course, may have been a factor, since no other Black man had received such a fellowship. But Locke refused to consider race a reason and surmised instead to Washington that the Kahn people were favoring older men who had teaching experience. If that were true, then there was nothing left for him to do but to postpone returning to Berlin, obtain a teaching position in the United States, and apply for the fellowship again the next year. In truth, it mattered little why the Kahn people had turned him down; without the fellowship he could not return to Berlin. From May 1912 on, he began to search in earnest for a teaching post at one of the Black colleges.

But which college? Howard University was the most prestigious and the most practical, located in the nation’s capital, just outside of the South and close to Camden and his mother. As the only bona fide Black university in America, Howard possessed a respected medical school, a well-regarded law school, and a federal subsidy that made it one of the most secure academic institutions in Black higher education. But in the fall of 1910, Locke had alienated officials at Howard. Apparently, someone at Howard University in a position of authority, perhaps Dean Kelly Miller, had written to Locke asking if he would be interested in the possibility of an appointment at Howard. The “offer” was exploratory and tentative, but Mary Locke believed it was serious. “They were willing to offer you a chair,” she wrote her expatriated son, “but were surprised by your letter. In light of it, they could not proceed further.”23 Most likely, Locke rebuffed their offer, because despite his severe financial problems in 1910, he remained committed to staying in Europe. Locke believed he could obtain the funds to finance his research travel plan, and he did not want a teaching commitment to stand in the way of realizing that dream. Locke may have felt that teaching at any Black college, even Howard, was a step down for him, and some of that condescension may have crept into his response. From Howard’s standpoint Locke’s lack of interest must have been surprising, since it was the most prestigious African American institution of higher education in the nation, and his best opportunity to have a college teaching position outside of the Deep South.

Apparently, the cool feeling toward Locke lingered, for when he visited Howard in November 1911, Locke contrasted the enthusiastic reception elsewhere on his Washington trip in a letter to his mother with the cool one at Howard. A return trip to Howard in February 1912, when Locke spoke to Cromwell’s teacher association in Washington, did not immediately increase his prospects. By the spring of 1912, Locke realized that he needed a go-between to resuscitate his candidacy. Again, he turned to Washington, who had been a member of Howard University’s Board of Trustees since 1907. After making a formal application for a position at Howard in July 1912, Locke wrote Washington asking whether he would “use your influence on my behalf” with the “proper authorities at Howard.”24 Washington spoke with Kelly Miller, who informed Washington that nothing was available in the College Department, but offered to speak with Dean Lewis B. Moore about a possible appointment in the Teachers College. The Teachers College offered the kind of teacher preparation courses that Locke’s mother and father had taken at the Institute for Colored Youth. Although this was not the academic appointment Locke hoped for, it was a job and he desperately needed one. Over the summer, Miller and Lewis worked out an arrangement whereby Locke would be offered a position in the Teachers College, with some minimal classwork in the College Department. To be considered for the position, Locke had to fill out application forms that required him to confront, once again, the issue of his Oxford University degree. Again, he put down that he had received a BLitt degree from Oxford in 1912. Actually, it probably was not necessary: having an AB from Harvard was quite enough to land a teaching job at Howard University in the early twentieth century. Moreover, his training at the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy probably played a greater part in recommending him for the kind of work he would be doing in the Teachers College. Nevertheless, by 1912, Locke had become committed to the notion of representing himself as a degreed student from Oxford. It certainly did not hurt his chances: on September 14, he received this telegram from Moore: “Elected Assistant Professor Salary One Thousand Dollars Congratulations.”25

Ironically, on the very same day, Locke received an offer from Washington to teach at Tuskegee if Locke had not already obtained work. Locke’s predicament recalls that of W. E. B. Du Bois, who received an invitation to Tuskegee days after accepting an appointment to Wilberforce University. In his autobiography, Du Bois reflected on how his life might have been different if the Tuskegee offer had arrived prior to the one from Wilberforce. Unlike Du Bois, Locke had a real choice, since both offers arrived the same day. But there was no doubt in Locke’s mind that he preferred Howard to Tuskegee, and he hurried off a letter to Washington to inform him that Howard had made the offer. “I was about to write you news of this, and to thank you for your very valuable and timely help in the Howard matter, when your letter with its still greater willingness to assist me in getting placed arrives to put me still more in your debt.” Locke tried to soften his rejection of Tuskegee by promising Washington to “serve your very best interests at Howard and elsewhere, until I more than repay you for your deep personal interest.”26 Both Locke and Washington may have realized that a “direct apprenticeship under” Washington might have had disastrous results for Locke—as well as for Washington. Washington knew that Locke was better placed at Howard. His abstract discussions of the comparative nature of racial attitudes and the conditions of cultural development were out of place at Tuskegee, where the practical training of the Black masses dominated instruction. Nevertheless, it would have added an interesting twist to Locke’s career if Howard had not made the offer and he had been obligated to go to Tuskegee. Perhaps teaching at Tuskegee would have inspired Locke to make southern African American culture the focal point of his interest, instead of the northern urban culture of New York and Washington, D.C. And the opportunity for Locke and Washington to team up to create a program of liberation at the intersection of art and economics could have been paradigm shifting for early twentieth-century Negroes.

But Locke could not overturn his bias and perhaps real fear of the South. His trip with Washington through the South had not stimulated Locke’s literary creativity. Although he talked of writing up his experiences, no literary sketches of southern Black life had resulted from the trip. While the South was the cradle of African American civilization, northern-born, it was not his civilization, so marked was his sense of social difference from the heirs of slavery. Locke regarded the Black South as best observed from a safe distance. In that sense, Locke remained indebted to Howard as well as Washington, for Howard had rescued him from a fate he must have regarded as just this side of death—the prospect of living in the Black Belt of Alabama in 1912.

Even so, Locke’s Howard appointment was a bittersweet victory. Remaining in the United States meant leaving behind the lifestyle that he and his friends Seme and de Fonseka had enjoyed in Europe. Instead of just visiting America long enough to secure funding to return to Europe, he was now settling into an American lifestyle, shouldering the tasks of race leadership, and closing off opportunities and freedoms that he had enjoyed living abroad. One of the most important was sex. Since his return to the United States in the fall of 1911, Locke had been living with his mother and the Claphans at 579 Stevens Street. Except for brief trips away from home, Locke lacked the kind of privacy he needed to entertain male guests in Camden. During the year since his return, he probably had contacted his former lover, Charles Dickerman, and enjoyed a rendezvous or two. He also attended a Central High reunion in January 1912 at which he may have revived old acquaintances and intimate friends. But these interludes of romance and possible sex were far more limited, hidden, and brief than those he had been able to regularly enjoy in Europe. At least in his first year back, returning to America meant giving up his sexual freedom for a life of far less frequent and far more compromised pleasures. In January 1912, he was approached by a Mrs. J. Elwood Camagy to address the Alpha Male Choral Society, a boy’s choir in New Jersey. After inquiring and learning that the singers were young teenagers, Locke took the time out of his busy campaign for the Kahn Fellowship to speak to the choir. The boys were mightily impressed with Locke; and so, apparently, was Locke impressed with them. Two days later, he wrote asking whether he might visit the boys at their next meeting. She said yes, although it is not known whether he returned. Here was one of the few compensations of his American return—he could use his iconic status to bring himself into contact with young men he could be attracted to. But such sublimated settings of hidden pleasure were a far cry from the kind of ecstatic homosexual freedom he had taken for granted in Europe. As his friend Lionel de Fonseka somewhat tactlessly recounted again and again in letters to Locke in 1912, London had exploded with vibrant new establishments that even the police knew catered to homosexual interests.

If Locke could not live the cosmopolitan lifestyle itself by returning to Europe, he could at least write about it, and in doing so, try and create a synthesis between his commitment to the race tradition, which he had eloquently outlined in “The Negro and a Race Tradition,” and his still-burning commitment to being a cosmopolitan, a player in a larger, universal community of thinkers and peoples. Just ten days before he learned of the Howard University offer, Locke penned a letter to Miss Cutting, his editor at the North American Review, which documents his continued theorizing about cosmopolitanism in 1912. A critical essay in two parts, “Cosmopolitanism and Culture” was a major statement of Locke’s philosophy of cultural pluralism and of what today would be called Cultural Studies, a demand for a criticism that “must be synthetic … must establish the linkages of facts, [as well as be] capable of administering a system of cosmopolitan culture. Had such a criticism kept pace in art and letters with our modern practice, our culture would have been more sound, more sane and more permanent. But with a steadily increasing need for it, criticism of that type has lapsed; so that for even the right conception of it, we must go back to Sainte-Beuve, to Taine and Renan, to Matthew Arnold.”27

“Cosmopolitanism and Culture” rejected what would later be called the New Criticism that studied a work of art removed from the world in which it arose. Instead, Locke suggested cultural critics return to an older form of criticism that Arnold’s generation of critics had advanced, even though their racial politics had been reactionary. Arnold had pioneered a new kind of cosmopolitan criticism, for Arnold had not been afraid to “universalize the English temperament even at the cost of denationalization in some essential respects.”28 But Arnold also had had the good sense to realize that something of the English national character must be preserved even when modern English criticism became cosmopolitan. Arnold’s criticism was both English and European; what Locke wanted to do was to expand that kind of cosmopolitan criticism beyond Europe to encompass the broader world of cultures, such that he and others could be both African American and cosmopolitan, even though he did not mention that dichotomy in this essay. He wanted to be able to insist that one’s national “voice” be retained in any world literature, while at the same time preserving the openness that allowed a culture to be open to others.

But Locke’s essay was noteworthy for being one of the first critiques of modernism from a postcolonial perspective. Locke made the argument that cosmopolitanism in literature and art was most often a raiding of other cultures, especially non-Western or colonial ones, for the forms the West could then appropriate for its own purposes, and then congratulate itself for being “cosmopolitan.” As in the earlier “Epilogue,” Locke argued true cosmopolitanism needed to be more than intellectual imperialism. Unfortunately, that had defined how the West had responded to Japanese art and culture:

A few years ago a discovery of Japanese art was the incident of the artistic decade, a startling revelation of civilization strange and new to us. A proper use of its contrast values was perhaps the very thing Occidental civilization most needed at the time. The diversity and incommensurability of the two traditions, the profound psychological and racial differences were a challenge and an opportunity for any culture professing cosmopolitanism. But the incident has come and gone without even having proved or disproved our notion of cosmopolitanism. The results of the encounter should have been momentous, instead of being in point of fact almost negligible, and the defects of our cosmopolitanism have been the causes of this failure: a faculty of appreciation too fluid to be retentive, an inability to comprehend and respect marked and representative national or racial contrasts because the sense for contrast amongst us has atrophied through neglect and disuse, and a facile eclecticism which refuses to interpret alien things in their own terms and according to their native values.29

Cultural respect for non-Western culture was still something Western artists no less than cultural custodians had a hard time practicing when they encountered sophisticated cultures that were not Western. However much the West congratulated itself on its cosmopolitanism, “there was more real power of assimilation in the subtle nationalism of Japan than in our diffuse and careless cosmopolitanism.”30

Rather than hobnob with Shakespeare and Plato above the color line as Du Bois had recommended, Locke wanted to build a cosmopolitanism out of the national traditions of the non-Western peoples. A sophisticated praxis of universalism was already practiced by non-Western cultures like the Japanese that put Western pretenses to cosmopolitanism to shame. Western cosmopolitanism was mainly a lifestyle for alienated intellectuals who wanted to escape the provincial confines that existed in any culture. Oscar Wilde had epitomized this attitude by calling the critic the physician of world culture. While such megalomania was ennobling of criticism, it ultimately was bad for art, for “the artist has found it impossible to use the universalized and disintegrated culture tradition as the constructive basis for creative work.” The literature and art that had expressed itself in terms of cosmopolitanism and universalism “has been for the most part so superficial and uncreative that it is not amiss to call it sublimated journalism.”31 Likely, Locke had the novels of Henry James on his mind, for they depicted in all their nuance the life of the “transit class.” Alienation was the concomitant of American cosmopolitanism, the elite disgusted with the lack of refined culture in America.

There was an alternative. Younger writers and artists were embedding themselves in the life of their people and discovering the life of the “province and the social underworld” through “the study of dialect, folk-lore, provincial mannerisms and community-life, and of the psychological exploration of those dark mental universes of the untutored peasant, the mentally abnormal, and the socially unfit.”32 Rather than trying to escape into expatriation, the true modernist artist, Locke the expatriate declared, needed to create literature out of the “intermediary units” of nation, locale, and province, that the critics claimed limited and destroyed art. Here were the lessons he had learned from traveling with Downes in London: the new literature would be a realism that knitted together with the local and subversive into culture. Locke put that theory into practice in his fictional village story “A Miraculous Draught,” also submitted to Miss Cutting. It developed a local legend about a Breton fishing village into a short story whose universal appeal came from how well it embedded the reader in locale. Art resided in the “smaller world, which criticism and cosmopolitanism have been breaking down,” an argument consistent with his Oxford thesis, “The Concept of Value,” that values emerged from and gained meaning in a social context. The particularities of the valuing literary experience—its history, its sense of place, and its social relatedness—produced aesthetic value, not paeans to drift and wayward seeking. Already evident in this essay was how far Locke had come from the Boston aestheticism of his Harvard undergraduate days. Philosophically, he was circling back to the position he articulated in that Cambridge Lyceum about Dunbar—that the true artist could not escape his or her birthright through cosmopolitanism.

Given how thoroughly he critiqued cosmopolitanism, one wonders why Locke called his essay “Cosmopolitanism and Culture.” Why not just focus one’s whole career and life on the “conscious revival of obsolescent bodies of culture tradition like the Celtic, Provencal, and the like?” The answer was simple: he needed cosmopolitanism to see something of value in his home culture. More concerned than Kallen that an unreflective embrace of difference and nationalism would lead one into a Gulag of imprisoning provincialism, Locke kept including the cosmopolitan, even when he argued against it, to remain free. Ethnic particularism must be part of a Hegelian-like becoming toward something larger, a path to a sense of world community, or become a trap. Cosmopolitanism and culture were a dialogue that defined who he was as an intellectual.

On a practical level, “Cosmopolitanism and Culture” was his way of talking himself into coming home. America was the only country that would support Locke as a Black intellectual. He knew that now. America also was where his mother was. But he would always be here and elsewhere, a liminal figure, an outsider to America spiritually and intellectually regardless of how much he symbolized Negro success for others. The trick was to use that alterity to create a more cosmopolitan “culture” at home. If he failed at that task, he would become little more than another Barrett Wendell, an exile at home.

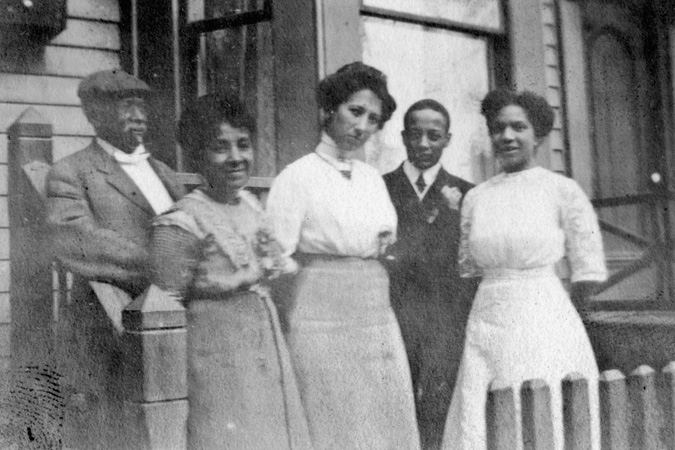

Locke, his mother, second from the left, and unidentified group, ca. 1915. Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.