23

Battling the Barnes

Where does an elitist, mildly Afrocentric impresario of the arts go in 1924 to get backing for his Negro awakening, given his penchant for alienating Black support? The answer lay there waiting for him after he arrived from Europe. Early in 1924, a short note came to Howard University asking for the name and address of a philosopher on “your staff whom I met in Paris a couple of months ago whose name I forgot.”1 The man who sent the note was Albert Barnes. When Locke met Barnes in 1923, he was a millionaire industrialist on one of his whirlwind trips to purchase European modernist and African art and engage anyone who listened in long, convoluted conversations about both. Barnes had built a mansion in Merion, Pennsylvania, and assembled one of the largest collections of modern and African art in the world. He had formalized that collection as the Barnes Foundation in 1922 to thumb his nose at the Philadelphia art establishment, which he believed was dominated by mindless bluebloods who knew nothing about modern art and looked down on him as uncultured arriviste. Like Locke, Barnes was born poor in Philadelphia but had graduated from Central High School at the bottom of his class and attended graduate school in chemistry, in Germany, without obtaining a PhD. He also shared with Locke a capacity for duplicity. After years of study, Barnes lacked the ability to create new chemical compounds. So he teamed up with a German chemist whom he brought to the United States and encouraged to create a silver nitrate compound called Argyll, which Barnes later took credit for inventing. Barnes went on to build a company in Philadelphia to manufacture and distribute the compound, which made him millions. Barnes also had a visionary conception of what the corporation should be: he invested in the psychology of his workers and required them to attend classes on William James and John Dewey at his factory. Barnes wanted to overcome the alienation typical of the American workplace and foster the kind of creativity among his workers that would make them his equals. In practice, however, Barnes contradicted this philosophy with a dominating personality that ran the factory and everything about it with an iron will.

Gender and race shaped his notion of power. Barnes’s two closest assistants—young White women—were described by one man as his “shadows,” women who never articulated an idea that had not already been cleared by Barnes. Most of his workers were African Americans dependent on him for a livelihood and forced to participate in his educational programming whether they wanted to or not. Ever since his mother took him at the age of eight to a camp meeting outside of Philadelphia where he heard the itinerant preaching and religious singing of African Americans, Barnes had been convinced that Blacks had greater spiritual capacity than Whites. On the other hand, according to Arthur Fauset, who worked at the Barnes Foundation, Barnes “was sadistic: he loved to demonstrate his power, and fought to make blacks love it and him. One of his favorite sentences was ‘I told them [the white Philadelphia elite] that if they didn’t let me have that place for the museum, I would take my house and rent it to Negroes and see how they like that.’ ”2 As the philosopher Bertrand Russell, who worked at the Barnes Foundation in the late 1930s, put it: Barnes “liked to patronise coloured people and treated them as equals, because he was quite sure that they were not. … He demanded constant flattery and had a passion for quarreling. I was warned before accepting his offer that he always tired of people before long.”3 Clearly, Barnes and Locke would be well matched in the coming contest over who would be the voice of African art in America, since gender and race were issues of power for Locke as well.

Barnes was not the only rival Locke faced in what would become a battle royale over who would introduce America to the power of African art. Both Walter White and Charles Johnson were in the struggle over who would most profit from the effort to link the cultural significance of African art to the African American literary awakening.4 Johnson had been interested in African art since 1923 and wanted to publish his own article on the subject, along with Locke’s on the Barnes Foundation, in a special issue of Opportunity in the spring of 1924. Johnson also saw the African art issue as a hook to land Barnes for a much larger contribution of money to Opportunity along the lines that Locke had proposed to Lieber. If Barnes could be encouraged to make a long-term financial commitment to the work of the magazine, Johnson might be able to move Opportunity out of straitjacketed social reform publishing for the Urban League. Johnson respected Locke, but was wary of him. And Locke did not want to become Johnson’s boy. White aspired to become something more than an assistant secretary of race relations at the NAACP. Interestingly, the careers of two highly educated Black men seem suddenly to hinge on the successful advertising of an art form most Americans knew nothing about.

This was not the first time that Barnes had been approached to help fund and propel a complex project for social liberation. In 1919, Horace Kallen had contacted Barnes about his plan to create an international movement during the Versailles Conference to establish the State of Israel. American Jewish support for this idea was lukewarm at best, and international opinion was even more skeptical. Barnes, however, was supremely confident that if he were allowed to negotiate the issues, he could have the whole matter resolved in a matter of days. Kallen wanted Barnes in the delegation at Versailles, but Barnes decided not to go, in part because he would not head the delegation, and hence said he was therefore skeptical about its success. As would prove to be the case in his dealings with African Americans, Barnes wanted, indeed needed, to be the center of attention and have total power over any effort that included him.

Barnes was different from other potential patrons like Lieber because Barnes was an intellectual. He had developed a coherent theory of art, grounded in his early study of art with the American realist William Glackens, his reading the art criticism of Clive Bell and Roger Fry, and his personal conversations with contemporary European artists. Barnes imbibed early how to look at paintings as a play of forms, not as representations of the world. Barnes moved beyond Fry to insist these formal relationships could be studied scientifically to see what a painting had to teach. Barnes believed that this ability was a profoundly transformative experience, giving the student/viewer a sense of authority that Barnes believed traditional education denied students. Whether workers or art critics, those who “learned to see” pictures in this way could develop a new, modern subjectivity. In practice Barnes seldom allowed any but a few sycophants recognition as aesthetic visionaries; and he was always the one who decided who was one. His books, essays, and correspondence lambasted others, especially noted art critics, for not viewing art and teaching art appreciation his way.5

On January 24, Barnes wrote to Locke asking him to be put in touch with the best writings of the young educated Black community. Barnes felt he already knew a great deal about uneducated, working-class Black people, “with whom I have worked every day for more than twenty years.”6 But Barnes wanted a cross section of works by the “negro poets, writers, thinkers, musicians and other creators who have risen above the average” for an article he had been asked to write for Ex Libris, a Paris journal. The invitation was important to Barnes, even though the journal was essentially a mouthpiece for Paul Guillaume, Barnes’s close friend and art agent. Barnes was pleased with the list Locke sent. He wrote back: “isn’t Miss Grimke a star of the first magnitude?” Locke was glad he did not have to respond to this in person, since he did not much like Miss Grimke’s work. Locke’s assistance was enough for Barnes to grant Locke’s request to visit the Barnes Foundation, but he wanted Locke to help him get his article republished in an American journal.7 Johnson reasoned that Barnes might allow the essay to be published in Opportunity, which might further attract Barnes to the fold of White supporters of Opportunity’s program.

At Johnson’s urging, Locke had invited Barnes to the Civic Club dinner, where he was enormously impressed with James Weldon Johnson, who spoke. But a problem emerged after the dinner. Walter White was seated next to Barnes and during the evening’s conversation, discovered that Barnes was an authority on African art. Apparently, White also wanted to write on the larger significance of African art and was then working on his own article, “If White Were Black,” on Black art and its broader implications, to be published in H. L. Mencken’s newly launched American Mercury. White made the mistake of writing an obsequious letter to Barnes asking him to critically examine a draft of the article.8 Barnes replied immediately:

You wish my opinion, you told me, upon what you have written upon negro plastic art. I’ll give it [to] you frankly because I want negro art to come into its own, on its own merits and discharged of the load of bluff, bunk and nonsense with which it is now burdened. Hence, I think that practically everything you have written from page four to page eight inclusive should never, for the negros’ [sic] sake, be published.

As if that rebuke was not enough, Barnes went on to detail:

What you state in many cases as facts are demonstrably untrue. Stewart Culin is one of the most loveable, other-world souls that I know; he is also a mental cripple, a hopeless doddering old ignoramus in anything which relates to art. [Carl] Einstein is a mental giant and connoisseur compared to him—that doesn’t detract anything of truth or sobriety of statement from my public assertion the other night that Einstein is a colossal bluff. De Zayas is in somewhat the same class as Einstein with dullness substituted for Einstein’s Clive Bell-like counterfeit thinking in smooth, slick language. But don’t take my word for anything I’ve just written upon those men. For the sake of the negro we both love—the negro who is a clean, simple, honest person—I suggest that you go to Paris and ask Paul Guillaume, the man who was the first to recognize what negro sculpture is as an art form.9

Barnes suggested to White that he “let the sole reference to negro plastic art be what Roger Fry has written. The rest of your references are the literary equivalents of prostitution.”10

What Barnes really objected to in White’s article was his references to other Whites as authorities on African art. To show who was really the authority on African art, Barnes sent White a copy of his own article, along with a letter he had written to Charles S. Johnson defining what was significant about African art and his strategy for bringing that significance to the American public. More than just promoting his own article, Barnes was enlisting Johnson and the other “fine brains I saw at work the other night” at the Civic Club dinner in his worldwide crusade to gain the long overdue recognition for West African art that had been denied it by White institutional interpreters of art. Barnes, however, did not think much of White’s ability. “I saw the other night,” Barnes wrote Locke of White, “that he’s a light-weight but his manuscript has revealed a cheapness which I hardly suspected.”11

White, however, seemed not to realize how much Barnes disliked his article and wrote Barnes asking if he could quote from “The Temple” and the letter to improve his own article. Barnes replied that such liberal quotation as White suggested would compromise the value of his own article. Barnes then had Johnson send copies of his articles, “The Temple” and “Negro Art in America,” to H. L. Mencken at the American Mercury for consideration for publication. As he wrote White, “That need not conflict with your article for the same journal because what I have to say is the logical preparation for your statements.”12 Mencken replied that he did not publish articles at that time on foreign subjects and that he already had an article commissioned on Negro art by White. That infuriated Barnes. He then demanded that White return his article and the letter immediately and threatened White and Mencken with legal action should his name or his words be mentioned in White’s article.

Barnes believed the Mercury was a better venue for his article than Opportunity, and once Mencken rejected him, Barnes became consumed with destroying White’s reputation. He proposed to Locke and Johnson that James Weldon Johnson, the secretary of the NAACP, be made aware of White’s “betrayal” of the Negro in his article. Barnes also had laid a trap for White: “In my second letter to White I suggested a conference with C.S.J. and J.W.J. in the hope that one of them would get wise. White, I think, is a personal pusher, and he may see what I meant and duck the conference.” White did “duck the conference”: he had the advantage over Barnes of having access to the American Mercury to express his interpretation. And Barnes had put White in an almost impossible position: he discredited all of White’s references to authorities in his article, but then refused to let White cite the only person that Barnes approved of: himself. Despite his stated desire for collaboration in advancing the cause of African art, the cause was mainly to advance his authority on the subject. Once he realized Mencken would not publish his article, he wrote White telling him that “the negroes with whom I work read your article” and had prepared a letter to be sent to the NAACP stating that they believed it should not be published. Barnes then stated that he had succeeded in “stopping the proposed formal protest,” but with the implied threat that if White failed to comply with Barnes’s wishes, he would have the letter mailed. Barnes also wrote Locke that he left open the possibility of a public debate with White and that, if he could get White to take the bait, he “could be eliminated from negro public life.” This conflict said something profound about Barnes: he was someone who could not tolerate anyone rejecting his self-promotion. What he did not realize was that he actually was modeling behavior for his erstwhile ally in this campaign against White: Alain Locke.

Being narcissistic himself, Locke quickly realized that it was unlikely Barnes would fund the independent arts institute Locke desired. Already astute at sizing up adversaries—and especially White ones—he sensed Barnes was the type of White man who needed Black people around to worship him, but would rebel at supporting someone else’s operation. So to feed that need, Locke recommended a number of African American intellectuals and artists to spend time at the Barnes Foundation, from Arthur Fauset to Aaron Douglas, the St. Louis–born illustrator and budding Black artist. Fauset was genuinely interested in a revolutionary, working-class pedagogy and for a while thought that Barnes’s system of John Dewey–like educational radicalism could be revolutionary. The Aaron Douglas connection served better Locke’s main agenda to gain access to Barnes’s magnificent African art collection for African American artists, for Locke believed that if Black American artists could be exposed to African art it would reawaken in them a visual arts facility that had been atrophied since slavery.

Locke was attempting to use Barnes to gain access to a Black art form that White people controlled in Europe and America. In 1924, African art was not readily available for viewing in American collections. A sense of Locke’s motivation in this context comes from Fauset: “Locke was insatiable when it came to things having to do with acquisitions that were going to be important in the black peoples lives.”13 Whereas Barnes wanted to get control of African art to enhance his reputation as a radical arts theorist, Locke wanted control of African art as a Black people’s birthright and as a means to convince contemporary Black artists that they were heirs to a mighty African visual arts tradition. It only would be a matter of time before conflict between this new, overweening father figure and the upstart virtual son came to a head.

After several postponements and delays, Barnes finally had tested Locke and Johnson enough to allow them to visit the Barnes Foundation on April 6. Located in a beaux arts mansion designed by Paul Cret, the Foundation welcomed the pair through the commanding neoclassical entrance into a round main hall. There, the six-foot-tall Barnes lectured the two diminutive Black intellectuals all day. When Barnes was not lambasting Walter White and his transgressions, he was expounding on African art and European modernism and the psychological principles he used to arrange the art on the walls of the galleries. Johnson was not exaggerating when he wrote Barnes afterward about “how extremely I value the opportunity which you made possible to be in contact with your amazing collection of modern and primitive art and with your own trenchant, kaleidoscopic intellect.”14 This visit may very well have been the first time that Johnson had seen African art up close. It was not, of course, the first time for Locke. He had seen a selection at Guillaume’s Paris gallery in July, and, likely before, while he was a student in Berlin.

Nevertheless, the visit awakened something new in Locke and catalyzed an immediate and dramatic shift of emphasis in Locke’s writings about things African—from his earlier focus on North and East Africa to one firmly attentive to West Africa. Little to no formal discussion of West African art existed in Locke’s writings before this visit, and a considerable, wide-ranging, commitment to such art erupted afterward and continued for the rest of his life. At the Foundation that Sunday, he saw clearly how he could use African art to advance his cultural agenda. Something emotional clicked as well, for afterward Locke became an avid collector of West African art.

Locke also imbibed Barnes’s enthusiasm for African art’s significance to modern art. Barnes displayed African art alongside modern European art and demonstrated its influence on cubism and modernism with unmistakable visual comparisons. The arrangement of the two bodies of art together showed that people of African descent had a claim on the most powerful art revolution of the twentieth century and armed visitors with compelling evidence of the influence of African art on cubism, especially. In the 1920s, radical modernists believed that African art had directly influenced Pablo Picasso and others, some even going so far as to argue that French artists had copied the African art forms verbatim. The difference was that Barnes collected the art that proved the point. Barnes had collected African pieces that directly correlated to these modern art creations, sometimes after conversations with the European artists themselves about their inspirations for their works. Seeing those eye-popping interconnections made clear to Locke and Johnson that African art was on a par with the best of European art—ever.

The day after the visit to the Barnes Foundation, Johnson swung into action. He wrote Barnes that he planned to publish Barnes’s article “Negro Art in America” in Opportunity in a special May issue dedicated to African art. Johnson was eager to move ahead with the special issue, especially in light of possible competition with White’s article in the American Mercury. Johnson also planned to include his own article in an issue, but was overwhelmed with work and other responsibilities in April and had to be away from the office in the weeks leading up to publication. In Johnson’s absence, Locke made most of the decisions about photographs, layout, and so forth, for the issue. This was only one of several occasions in Locke’s life in which he ghost-edited issues, exhibitions, plays, or books, but this time it caused him great stress. Johnson wondered why Locke became so agitated during the mock-up. “I think it was made very clear that we were dealing with materials about which your judgment was superior even to mine, and that you would be in New York to see the proofs and make suggestions on the final form. … I am glad that what could easily have been guessed as my wishes in the matter were respected. … But for goodness sake don’t let African art be your Nemesis.”15

Why was Locke so disturbed? A conflict between Barnes and Locke is the most likely source. After the issue appeared, Barnes was furious because he believed that Locke had plagiarized his ideas in Locke’s article “A Note on African Art.” While the Opportunity issue also included Barnes’s article “The Temple,” Locke’s article better communicated the ideas that Barnes had communicated orally to Locke and Johnson. John Dewey claimed Barnes suffered from an inferiority complex that inhibited him as a writer, and he often sought others to codify his ideas. But Barnes was intensely jealous of anyone he did not choose expressing his insights. Locke’s stress may have been linked to his knowledge that Barnes would believe he had been overthrown by Locke’s more powerful presentation of the notion that African art was the leading edge of a modernist revolution in aesthetic form. Barnes’s article was stuck in the details of his own personal entry into African art and Paul Guillaume’s Paris studio, which left the door open for someone, in this case Locke, to give better expression to the central idea—that African art was the most significant contemporary influence on modern art and was produced by Black people in Africa. Barnes felt cuckolded, and Locke knew he would feel that way.

Barnes was angry even though Locke fawningly acknowledged Barnes and his collection throughout “A Note on African Art,” as did the rest of the issue. The editorial page had a tribute, “Dr. Barnes.” The issue also included Paul Guillaume’s article, “African Art at the Barnes Foundation,” with numerous credited photographs of Barnes’s artwork. Moreover, Barnes’s own essay, “The Temple,” credited Guillaume as the original person to recognize the importance of African art for modern art and lauded his studio for creating an atmosphere of free intellectual exchange where Barnes learned much from Roger Fry, Jacque Lipschitz, and Waldeman George. He concluded: “No psychologist would deny that what we like, we must share with others to obtain its full savor.”16

It seems, though, that when Barnes savored what he had shared with Locke at the Barnes Foundation, it left a bad taste in his mouth. This kind of sharing is precisely what the mentoring role in patronage is supposed to be about. Locke was essentially the mentee—the understudy to the master and saying in his own words what Barnes wanted said. But Barnes had not yet said it well in print himself. Of course, Locke was also the only aesthete, with a world-class aesthetic rather than social science education. His exposure to modernism in his years at Harvard, Oxford, and the University of Berlin, and also with his friends like Dickerman and de Fonseka, allowed Locke to understand Barnes and use his insights nimbly to advance his own cultural agenda. Barnes had made the mistake of lecturing to the one Negro who understood him.

After the issue was published, Barnes wrote Locke to say that he did “like the African Art issue very, very much and it did, as you say, spread out the subject nicely.” More privately, he also did a ten-page exegesis of Locke’s article, going line by line, and writing “mine” by those sentences he felt were taken from his talk and writing “platitudes” by those lines that expressed Locke’s ideas. Barnes was also displeased Locke had had the temerity to inject his own ideas and agenda into his discussion of African art. Locke had constructed himself as an authority on African art through the language and tone of the article. And Locke had not thanked Barnes enough. Lack of gratitude on the part of Negroes who received patronage was a frequent lament of White patrons of the period.

Barnes then took another jab at Locke in the letter: “This damned nigger question is getting to be quite a time-consumer for me. Twice a week I lead an attack on some of their own prejudices and every once in a while it gets so warm that I keep my eye peeled for a razor-flash.”17 The use of the word nigger, at a time when Du Bois and others were demanding its erasure from respectable discourse, was both Barnes’s way of degrading Blacks and asserting his entitlement to use the term because he was so “in” with Blacks. But the reference to the flashing of the razor, while a demeaning stereotype of primitive Black violence, also revealed more than Barnes intended. If truly a sign of Black anger, it suggests that even the working-class Blacks in his employ were beginning to tire of his presumption he knew better than Negroes what was best for them.

Barnes’s idea—that African art had taught European artists what was, in essence, modern art—was quite radical in 1924 and is still resisted by canonical modernist art history. But Barnes had the art to prove the point, and this is why Locke put up with Barnes for years: he had the art Locke needed to make his stronger point that European artists had stolen the formal inventiveness of African artists to launch modernism in art. A thirteenth-century Zouenouia statue, whose photograph from the Barnes Foundation Locke published on page 136 of his article, was followed by a photograph of the Modigliani stone on page 137 to show how strikingly similar in form, conception, and sculptural execution the modern copy was of the African original. Barnes’s collection showed more than coincidence or psychological obsession with exorcism- or fetishism-inspired modernist artists like Modigliani and Picasso—it was formal lessons that African art had taught European modernists of how to create paintings and sculpture conceptually, not representationally.

But Locke diverged significantly from Barnes in the use to which he wanted to put African art—to awaken young Negro artists to see African art as inspiration for making a great African American art in the twentieth century. Locke ended on a strong charge to Negro artists to follow their African ancestors, reject Western academicism, and create a revolutionary, formally new art of their own. Why? Because up until 1924, the argument for a Negro American art movement had rested on content—that Negro visual artists like their literary cousins should be encouraged to create because they had been denied that recognition in the past because of racism. Or a Negro art was needed, à la Du Bois, to fight against visual racism by creating an archive of beautiful, dignified Negro faces and bodies. But Locke articulated a different Weltanschauung for African American art—as a demand to build on the formal aesthetic genius of their ancestors to create a revolutionary new American art on the basis of form. The resultant article was no longer simply Barnes. The discovery of the African conceptual revolution in art by a Black intellectual was taken as permission for contemporary Negro artists to equal what European modernists had achieved. That was never Barnes’s intention. Once again, as with Hansberry, so with Barnes, Locke was not interested in valorizing the past, but in using that past to launch a contemporary art movement.

By making that change, Locke came out from under Barnes as his tutee, and regarded, in effect, Barnes as his research assistant, as someone who had been in the library, so to speak—or in this case the Paris galleries—had found some new research, delivered it to the professor, and now saw it stated in print. Of course, Black people were thankful for Barnes’s services, especially for delivering to them the knowledge that they did not need White people to create great art. Barnes’s theorizing was a breakthrough in acknowledging that African art had pioneered in effect, a conceptual art that opened a doorway to cubism and abstraction. Locke was grateful for that insight. But he refused to pay back Barnes for that knowledge by becoming his intellectual servant. Instead, as he did with Max Reinhardt’s observations, Locke used Barnes’s knowledge to launch his own subjectivity as the foremost African American authority on African and African-derived art.

Sometime in the writing of his article and the editing of the issue, therefore, Locke decided to accept himself as the Prometheus who stole knowledge from the man who acted like a god. He knew that Barnes would revile him as a thief. But Barnes himself stole this knowledge from others and peddled it—like his zinc formula—as his. Reinhardt had been more generous, perhaps recognizing he could never be the one to advance a Negro American artistic agenda. Barnes had no such humility: he wanted the credit for “discovering” African art and authority for determining the correct interpretation of it. Locke decided to appropriate while augmenting Barnes’s interpretation so effectively that Barnes could never prove Locke was wrong.

Of course, Barnes would try and discredit him, but the truth was that Barnes did not have the institutional network to stop Locke. Indeed, Locke through Johnson, and White through E. L. Mencken, had publishing access that Barnes lacked. He needed them even more than they needed him to get an airing for his ideas. And no matter how boisterous Barnes was, or how cavalier in throwing around the N-word, ultimately, he couldn’t control Locke and that made him exceedingly angry.

A corner had been turned. A New Negro was emerging, who did not have to kowtow to a White man who was “in the game.” Locke had been psychologically well endowed to resist Barnes’s hegemony, since after Locke’s struggle against his father, he had a deep well of Oedipal resistance to draw upon. But tussling with a pathological White man involved risk, for it required Locke and those after him to manifest a kind of courage in cultural combat with powerful Whites that seldom had been successful before. What made the New Negro subjectivity new was the willingness to assert that Negroes had a right to theorize about their aesthetic traditions and benefit from them without having to grovel for every nickel they received from White supporters. This position would be tested in the coming years.

But for now, the new attitude was evident in a letter Locke wrote to the Abyssinian minister Belata Heroui about an impending visit of White philanthropists. “I am sure, that since they represent … the characteristic attitude of the white race, which even when philanthropic, needs constantly to be watched and safe-guarded[. I am sure] that the Wise perspicacity and skilfull [sic] diplomacy of yourself and associates has already sensed this and met the situation adroitly. The interests which they represent can then be wisely used, without danger to that most precious of all things—Abyssinian national feeling and sovereignty.”18 The Barnes episode had been a case study for Locke in how such interests could be wisely used, but also wisely “watched and safeguarded,” lest they destroy the early shoots of “that most precious of all things”—African American “national feeling” and cultural self-determination.

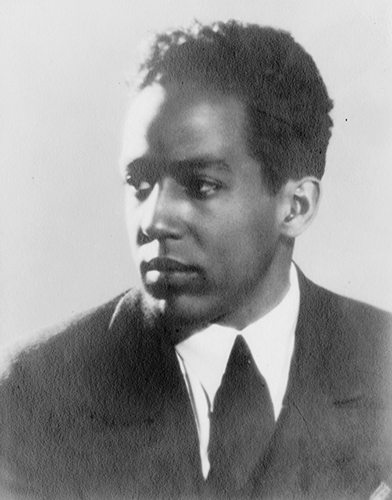

Langston Hughes, 1927. Photograph by James Allen. Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.