25

Harlem Issues

When Locke arrived in Washington the third week of September 1924, he found two letters. One, from Claude McKay, encouraged him to get professional help with his problems. “You know if you’re neurasthenic,” McKay wrote, “you ought to see a psycho-analyst—if you cannot help yourself. … Dr. A.A. Taunenbaum of New York is a fine understanding chap. He’s a friend of mine—slightly neurasthenic himself[,] which makes him a better and more sympathetic analyst.” McKay closed the letter with the advice that “you’d better to destroy this letter.”1 Locke did not. He did not seek psychological help. While abroad, he had shared with McKay that sometimes he became so disturbed that the only antidote was random sex, which did not really cure the problem of his neurotic tension. It was also dangerous, aggravating his paranoia about discovery as a homosexual. McKay, however, did not know about Locke’s falling in love with Langston Hughes. The other note was more important. “I am sending this to Howard University in case you go directly to Washington,” Paul Kellogg, the Survey Graphic editor wrote, “just as a bit of welcome and an expression of renewed interest in the project.”2 Kellogg had not known that Locke had been working feverishly on his introductory essays during his last days in Europe.

The two notes were connected. Having fallen in love and been rejected, Locke returned to the United States an exposed wire. Work on the New Negro had been a balm in San Remo; now, work on Harlem provided a cladding to cover his damaged but pulsating interior. Partly, it was Harlem itself—a teeming city within a city filled with Negroes from all over the world who did not judge him, as he felt judged in Washington. Harlem attracted “the African, the West Indian … the Negro of the North, the Negro of the South … the peasant, the student, the business man, artist, poet, musician, adventurer and worker, preacher and criminal, exploiter and social outcast”—the last a reference to himself—such that finding one another in its non-punitive environs, a race bonding and community emerged.3 In Harlem, Black people escaped the normative gaze of a White society, because they immersed themselves in a Black majority. Surrounded by the successful and the criminal, Locke felt at home in Harlem, because he was a little of both.

Kellogg’s note also foretold that the work on the Harlem issue would bring some internal harmony to Locke’s neurotic tensions. For the first time, he was filled with a more powerful sense of advocacy than had suffused him when writing about Cairo or Black soldiers on the Rhine. Now, he was fighting for an American home for Black creativity and for his own kind. Writing about Harlem transformed him into the father—the seed layer whose prodigy was a place, unique even among Black American cities, for the poetry of the Black experience to blossom. Locke argued that Harlem, unlike Chicago or Philadelphia, was a twentieth-century mecca devoted to the production of great literature and art just as Charles Eliot Norton and Barrett Wendell had predicted for Boston in the nineteenth century. But Locke was also fathering a gay Black community in Harlem for ostracized queer creatives. They would be front and center, the leaders, the representative men—and they were usually men—rather than the Black bankers, protest leaders, and preachers. Harlem was the street on which the outliers could walk in peace. They would create a new African American literature, theater, and visual art that could, if allowed, transform American culture. Locke’s response to Kellogg’s letter was to build something far beyond what Kellogg originally had intended—a permanent house in the American imagination where young, tortured, and resilient Black technicians of the sacred could say “I’m home.”

But the two letters at 1326 R Street, NW, also foretold conflict. For the first time in his career, Locke was in charge of a White publication, something that ensured a broader, more national platform for a Black message. Such a strategy carried risks. Though Locke was guest editor, Paul Kellogg made the final decisions. Choosing to work closely with the Survey Graphic’s White editorial staff, Locke would have to tolerate the timid liberalism of progressives, who, despite their modernism, did not want to produce an issue that challenged directly the racial etiquette of segregation, even while they celebrated African American culture. How was Locke going to represent the bubbling racial self-assertiveness of young, Black writers in a magazine whose editorial staff did not want to be known afterward as the voice of militancy or social equality? Locke wanted a White publisher because he believed that Black liberation would proceed further if it dialogued with White attitudes. To do that forced him into a more difficult position than Harold Cruse and other critics cited—he had to create a modus vivendi between Black self-determination and White cultural hegemony if Locke’s “little renaissance,” as he later called it, was to become the nationally and internationally known Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. By the end of the Survey Graphic project, Locke would call himself a “referee” of feuding camps. But rather than feel daunted, Locke seemed buoyed by the challenges and plunged right in.

A subtler conflict underlay the racial one. While Kellogg, the White editor, made the final decisions, Locke was the “head Negro in charge” with a unique opportunity to shape the definition of the New Negro in his own image. Locke had to mediate between his role as a caretaker and representative of younger artists’ interests and his own increasingly powerful interpretation of what he thought the New Negro should be. The tension was not simply external; it was a tension in Locke. There was an aesthetic Locke who avoided conflict with Whites and wanted a notion of Blackness grounded in beauty and a radical Locke who had developed an imperialist analysis of Black-White relations that had appeared in the Race Contacts lectures. Which was going to dominate the Harlem issue? And which was going to make his reputation as a Negro spokesperson in the politically conservative 1920s? Here was a chance to perform on a national stage the through line of his life—to be a harmonizer of divergent values, personalities, and communities via art. He was not going to let that slip through his fingers.

Conflicts that fall epitomized, however, the dangers of his new calling. Locke had written his friend McKay and told him that he did not want to publish “Mulatto” in the Survey Graphic’s special Harlem issue, because it is was too strong for the White people at the Survey Graphic On October 7, McKay wrote back angry.

Your attitude towards the “Mulatto” is that of Booker T. Washington’s in Social Reform, Roscoe C. Bruce in politics and William Stanley Braithwaite in literature. It’s a playing safe attitude—the ultimate regard of which are dry husks and ashes! Why mention the Liberator? It’s a white paper and “Mulatto” is not stronger than “If We Must Die” which the Liberator first published. I guess if the Liberator had not set that example not a Negro publication would have enough of the “gut” you mention to publish it! It isn’t the “Survey” that hasn’t gut enough. It is you. The survey editors would not mind. There are many white people that are longing and hoping for Negroes to show they have “guts.” I will show you by getting a white journal to take Mulatto. Send it back to me at once. No wonder the Negro movement is in such a bad way. No wonder Garvey remains strong despite his glaring defects. When the Negro intellectuals like you take such a weak line!4

McKay concluded his letter by threatening to pull all of his poems from the Survey Graphic if Locke did not publish “Mulatto.” The threat went deeper. “I do not care to be mentioned at all—don’t want to—in the Special Negro number of the Survey. I am not seeking mere notoriety and publicity. Principles mean something to my life. And if you do publish any of the other poems now and leave out ‘Mulatto’ after this protest you may count upon me as an intellectual enemy for life!”5

While surprised by McKay’s reaction, Locke was unfazed. “Glad to have your ultimatum,” Locke wrote back, “and will publish Mulatto subject to approval by the Survey.”6 That last line is revealing. Although critics have taken at face value McKay’s main contention that Locke rejected McKay’s poem because of Locke’s political conservatism, it seems clear that Kellogg surely would not like a poem in the Harlem issue that advocated murder of one’s White father as the appropriate response of a mixed-race “bastard” parentage. The poem’s expression of patricide as a means to the “utmost freedom that is life” struck a note of racial hate not present elsewhere in the issue. The poem focuses attention on White racism and suggests that murderous retaliation was the right response to such racism. Probably, Locke told McKay the truth that Kellogg and the Survey Graphic staff did object to the poem.

Kellogg is on record as opposing another submission to the issue that drew attention to Black life as a consequence of White racism. In the case of Kelly Miller’s article, “Harvest of Race Prejudice,” Kellogg wrote Miller himself asking him to shift the focus from White racism to the pathologies of the Black community. “Your essay focuses on the numerous instances of white racism with which our readership is already familiar. We are striking out in a new direction in this issue, one that focuses on the life and attitudes of the black community over those of the white. Can you not bend your article toward documenting those examples of black racism and Anti-Semitism which are the unfortunate harvest of color prejudice in places like Harlem?”7 Kellogg was not neutral when it came to submissions that focused on White responsibility for racism. That was precisely what the poem “Mulatto” did. It’s doubtful Locke would have written McKay about the poem if the special issue was being published by Opportunity instead of the Survey Graphic. While Locke objected to the poem for his own reasons, it seems likely he was reflecting the feeling of the magazine when he wrote to McKay.

But it’s also doubtful Kellogg would have removed the poem without Locke’s support. For a White liberal editor of a magazine devoted to Black self-expression in this number to refuse to publish McKay’s poem would have carried risks. If that kind of information got out into the Black community, the legitimacy of the project could be undermined. Interestingly enough, Miller refused to change his article to meet Kellogg’s demands, and Kellogg did not keep that article out of the issue. In the end, the final decision not to publish the poem probably was Locke’s.

Why did Locke want to drop the poem? “Mulatto” was part of the militant counter-discourse of the New Negro that held White people accountable for past crimes, a protest Negro literature evident as early as Grimke’s Rachel that Locke saw the New Negro poetry displacing. It’s elegy to retaliation also had social relevance in that retaliation against White rioters had been a significant moment of New Negro consciousness in the Chicago race riot of 1919, as McKay had memorialized in “If We Must Die.” This poem, however, implied that children of mixed-race couples should give in to murderous rage toward their White fathers. But Locke’s question would be, after you murder your father what then? Locke may have resented the poem because it brought up unconsciously his own murderous declaration of independence from his father. Thus, the problem of how does the son become a man was not specifically racial, even though, in some sense, the poem’s brilliance was to cast it in those terms and make a common psychoanalytic journey a racial one—that the Negro to be free must kill the White father within. Locke’s argument might be that it was not the right time. But in some ways, it was: if the New Negro Renaissance was to effect a real catharsis, create a truly unique literature, was not a symbolic murder of what Cornel West called the “white normative gaze” precisely what was needed?8 McKay had declared for a radical, Oedipal liberation that was strangely appropriate for its time.

But this was not Locke’s message in the Survey Graphic. Locke’s philosophy of art was to create a kind of cocoon of positive self-valuation within the temple of art, to turn away from self-destructive impulses connected to White patrimony of various kinds, in order to survive at something that was impossible for most White people to imagine—that Negroes could become first-order artists and intellectuals. Locke wanted to remake the Negro’s past for psychic support in the present and future. Emerging in the era of the triumph of Jim Crow segregation, the Negro artists or intellectuals lacked any legitimacy in White America. There were few affective sources of support for a Black vocation of the mind. Faced with such formidable opposition, Locke felt that attacking that edifice was fruitless.9

Could not even the mixed-race son of a White rapist refuse to define himself in reaction to that fact and instead embrace the sun? Locke found that kind of internal freedom in Langston Hughes’s poem “Dream Variation,” in which the young Black person “flings” his or her “arms” and dances “till the white day is done,” an exaltation of life despite challenges, where Whiteness becomes something to be waited out rather than attacked, an anachronism like the day about to become night. Locke was looking for poets to show a kind of moral superiority over racism, rather than a getting down in the muck with the enemy. But getting dirty was also part of the New Negro, and Locke had already started to clean it up.

If Locke rejected the poem purely on the basis of his aesthetic judgment, why did he not explain it as such to McKay? Locke could have written to McKay and said what every editor has said to an author at some time or other, that is, “Hey, I don’t like that poem and I’m not going to publish it in the Survey.” Locke could have rejected the poem more effectively without eliciting the White authority. Why didn’t he? Something in Locke may have made it difficult for him to simply assert his authority with McKay. Perhaps because they had been friends, it was difficult for Locke to tell him he detested the poem. Locke had developed the tendency to avoid taking the responsibility for difficult decisions. He was still hiding behind a mother figure, in this case Kellogg (before it was Charles Johnson), instead of stepping out front and rebelling against the overprotective mother in him. In this, the Black Victorian in him became an easy target for McKay and other young artists who would come to suspect that Locke’s literary decisions were based more on racial politics than aesthetic judgment. But in some sense, at this stage of the movement, his decisions had to take into account racial politics. Locke’s role as guest editor of the Survey Graphic was to move Black writers into the mainstream. In the end, the price of mainstream access was compromise on message. Locke knew that, and so, in the end, did McKay, although neither seemed willing to admit it.

In November, Locke wrote to Kellogg: “McKay in his last letter is off his high horse. Says that perhaps I know best, etc. I take that as permission that we don’t have to use ‘Mulatto.’ ” When the Survey Graphic special number was published, “Mulatto” was not one of the poems included, and McKay did not seem that upset. He wrote the day of its publication to ask Locke to find some AME hymns, and stated, “But how can I fight you from way over here? How can I? So better let it be as it is. Tell me about yourself?”10 In the immediate aftermath of the publication of the Survey Graphic number, McKay made little complaint, perhaps because he needed his relationship with Locke to continue, since Locke supplied him with money on a regular basis.

Not publishing “Mulatto” did not mean that Locke avoided all militant poems in his selection for the issue. Locke did publish McKay’s other militant poem “White House,” which, despite his change of its title to “White Houses” (to avoid the possibility that readers might see it as a critique of the presidential residence) remains a powerful protest against the exclusionary power of racism. What distinguished this poem from “Mulatto” in Locke’s thinking was the way the poem contained its anger in the resolve to struggle against prejudice, as in its last two lines that perfectly captured the mood Locke wanted to hear from New Negro poets:

Oh I must keep my heart inviolate

Against the potent poison of your hate.

Locke acknowledged in his essay “Youth Speaks,” which introduced the poetry section in the Survey Graphic, that “there is poetry of sturdy social protest, and fiction of calm, dispassionate social analysis. But reason and realism have cured us of sentimentality: instead of the wail and appeal, there is challenge and indictment.” From Locke’s perspective, “White Houses” was challenge and indictment, whereas “Mulatto” was “wail and appeal.” Interestingly, Locke’s judgment about “Mulatto” seems to have been borne out by the canon, since it is not one of McKay’s poems reproduced in anthologies of Black literature. Locke preferred the McKay poem “Like a Strong Tree,” with its stirring lines:

Like a strong tree that in the virgin earth

Sends far its roots through rock and loam and clay,

* * *

So would I live in rich imperial growth,

Touching the surface and the depth of things,

Instinctively responsive unto both,

Tasting the sweets of being and the stings,

* * *

Like a strong tree against a thousand storms.11

That was the note Locke wanted in the Survey Graphic, the sound of poetic strength and resiliency in spite of oppression, not wails of bitterness and ill-founded revenge.

Other poems signaled the notion of spiritual triumph over the materiality of Blackness lived by women in America. Anne Spencer’s Lady, Lady combined racial identification with a feminist exposé of Black women’s alienation.

Lady, Lady, I saw your face.

Dark as night withholding a star …

The chisel fell, or it might have been

You had borne so long the yoke of men.

Locke wanted poetry of the Black particular that showed how a universal message emerged from Black lives:

Lady, Lady, I saw your hands.

Twisted, awry, like crumpled roots,

Bleached poor white in a sudsy tub,

Wrinkled and drawn from your rub-a-dub.

Service to Whites and patriarchy had aged a woman nevertheless triumphant in the eyes of this Black woman poet.

Lady, Lady I saw your heart,

And altered there in its darksome place

Were the tongues of flame the ancients knew,

Where the good God sits to spangle through.12

Rather than a poem of protest, Lady, Lady burrowed into the pain of Black women’s labor to excoriate what it meant to be Black, working class, and female in post slavery America. Here was what Locke was after—a sense of Beauty that challenged Western norms of who and what was beautiful and found it in the materiality of Black life.

While his controversy with McKay simmered, Locke traveled to New York over the October 24–26 weekend to meet with Kellogg and assess the status of the issue. At the offices of the Survey Graphic, he saw firsthand what manuscripts had come in, and how the Survey Graphic staff had reacted to them. He supervised the final draft of the letter that the Survey Graphic sent out announcing an art contest of work by African American artists that could be used in the magazine. His nemesis Albert Barnes had even consented to be one of the judges for the contest. Locke and Kellogg also discussed the paltry number of contributions that had come in by the end of September. Locke’s first choice to do an article Locke wanted written on the psychology of the New Negro, had not yet found an author, since Benjamin Karpman, Locke’s psychological confidant, had backed out over the summer. Even more disheartening, some of the submitted articles were so incomplete or poorly written that they had to be rewritten before being submitted for serious copyediting. It would be impossible to get the issue out by December, as Kellogg had originally planned. On Saturday, October 25, Locke took Kellogg to a Roland Hayes concert, to get a breather from the pressures of the looming issue.

That weekend also probably included Locke’s first opportunity to look at the art Winold Reiss had produced for the issue—either at Reiss’s studio at 12 Christopher Street or the Survey Graphic offices, where Reiss brought photographs of the artwork from time to time. After his summer in Woodstock, Reiss had started drawing portraits of African Americans from Harlem even before Locke got back from Europe. Reiss possessed a remarkably open, warm, and infectious personality, one he had used to great effect in his travels to Browning, Montana, in 1919 to draw Blackfeet Indians. Arriving in Browning in a snowstorm in November of that year, this Prussian artist quickly made friends and got prominent Native Americans to sit for portraits for him. He had done the same in 1922, when, armed only with his pastel boards and pencils, he had traveled on foot to rebel-infested Tepotzotlan and Cuernavaca, and drew bandits and Zapatista soldiers in compelling and sympathetic portraits. He began to do the same thing in Harlem, traveling uptown with his brother Hans, who spoke better English, to stop and entice African Americans, whose faces struck his fancy, to pose at his studio at 12 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. By the time that Locke and Kellogg had started meeting, Reiss had already produced such portraits as “Mother and child,” “Girl in a white blouse,” “A Woman from the Virgin Islands.” Reiss also had drawn a portrait of a man from the Congo, who lived downstairs from Reiss’s studio and refused to cut his hair. The resulting portrait, “Congo: a familiar of the New York studios,” with its globe-like Afro, became one of the most powerful statements of African identity in the issue.

Even though Locke had wanted to have an African American do the artwork, Reiss’s portraits already showed he was the right artist for the job. Visual art by Negroes was slow to materialize. The art contest he had organized the previous spring had failed to produce much quality work from African American artists. But Reiss’s portraits were powerful visual statements of Negro identity. What seemed like a contradiction to have a German artist illustrate a declaration of Black cultural awakening was actually a rich opportunity, for Reiss invigorated the image of the Negro with a Neue Sachlichkeit visual aesthetic that was altogether absent among American artists. His portraits broke with the caricaturist representations of Blacks in American popular and fine art traditions and also with the romantic bourgeois photography Du Bois used in the Crisis to create a counter-discourse to racist iconography. His portraits were powerfully etched moderns, enlivened by Reiss’s training in Jugendstil poster design that made their transference to print media result in no diminution in their visual power. Du Bois’s illustrations had the look of old Victorians. Reiss’s were modern. And unlike the visual satire of George Grosz’s cartoons, Reiss’s drawings placed the viewer face-to-face with the sitters who looked back with the seriousness of peers.

Locke would have more success getting Reiss to produce art that fit his agenda for the issue than he had with the writers. The portraits done so far were good but almost all of them were of working-class Negroes Reiss had met on the streets of Harlem. There were no artists and intellectuals, like Locke, represented so far in Reiss’s collection of sitters. They too, like the migrants from the South, the African, and the West Indian, were part of the new community Locke argued had emerged in Harlem. The gallery of pictures had to include their portraits to visualize their influence. Locke also knew that if he published an issue that just portrayed working-class Negroes the Black middle class would cry foul and declare the issue unrepresentative. But getting the normally reticent and cautious Black middle class to sit for a German artist was a challenge. Locke flew into action. He called on Elise Johnson McDougald, the New York social worker and women’s rights leader, to suggest some people who might sit for Reiss. She had emerged on his radar screen during his debate with Kellogg over whether an article on the Negro household should be included in the issue. Kellogg wanted something that would point up the problems and difficulties of Negro home life in Harlem. Locke resisted that idea, arguing that such an article was too sociological and controversial. Instead, Locke recommended a more broadly focused essay on women and the race issue. McDougald was a compromise choice, given that she was both a social worker and a women’s rights advocate. The resulting article, “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation,” better fulfilled Locke’s aspirations than Kellogg’s by boldly attacking the cultural issue of the representation of Black women in the popular media of the day and painting a compelling portrait of the self-consciousness of African American women fighting against such representations in their daily lives. Her draft of her article was turned in early and convinced Locke to ask her to bring some professional Black women to sit for Reiss. “I was glad to co-operate in making the Survey Graphic—Harlem number well-rounded. I took 5 young women down and he selected 3 of them.” One of the three, a portrait of Regina Andrews, became “The Librarian,” and a double portrait of two others became, “Two Public School Teachers.” Reiss also cajoled the strikingly beautiful McDougald to sit for a portrait. As McDougald noted, Locke initially declined to sit for a portrait.13

Locke also got artists and friends to sit for Reiss. A letter from Countee Cullen attests to Locke’s quick work. “Harold [Jackman] was here and had dinner with me this evening; he is quite beside himself with pleasure; he is to go to Reiss Wednesday for a sitting.”14 Jackman’s portrait, which Locke titled “A college lad,” was one of the most arresting of the assembled gallery, along with that of Paul Robeson, doing his Emperor Jones grin. In the end, Locke’s collaboration with Reiss in fashioning the gallery of portraits in the Harlem issue of the Survey Graphic made profound argument—the people themselves were the most spectacular offering of the Negro Renaissance, a new identity of American, and that subjectivity was more important than the literature that they produced. The New Negro was the thing.

Sometime in December 1924, Locke began to compose the imagery of the issue by selecting portraits that exemplified the argument of “Harlem.” He chose dark-skinned and light-skinned Negroes, the uneducated and “a woman lawyer,” girls and boys, independent women and mothers, laborers and dandies—all placed side by side to show a community of middle- and working-class Negroes. He visually represented “the African, the West Indian, the Negro American … the peasant, the student … the artist … musician, adventurer and worker” in a gallery of difference that put them in conversation with one another. The Survey Graphic itself visualized his argument that a “fusing of sentiment and experience” and a “great race welding” was taking place in Black America.15

Once Locke had the art side of the Harlem number under control, he turned his attention to two other pressing concerns: the paltry number of contributions that were ready to go to the copyeditor and financial support for the issue. Kellogg was trying to get Barnes to help pay for the publication, but Barnes, as usual, was tricky and elusive. The cost of the number was mounting, and to absorb that cost, Kellogg delayed publication. This special number was more expensive—with extensive commissioned artwork, numerous contributors, poetry, short fiction, and research articles—than others Kellogg had produced in the past. But while Locke worried with Kellogg over the issue’s cost, there was really nothing Locke could do to defray the costs—his relationships with Barnes and Lieber were not such as to allow him to approach them directly for funds. Without any way to advance the finances of the issue, Locke focused on revising and editing some of the weaker submissions.

Locke intervened in Arthur Schomburg’s “The Negro Digs Up His Past” and J. A. Rogers’s “Jazz at Home” most substantively. So poorly organized was Schomburg’s submission, Locke claimed, that he had to rewrite it. The resulting article was a collaboration. For example, the lead to the article reads: “The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future,” one of Schomburg’s recurring themes, though nowhere expressed as succinctly as here. Then, “Though it is orthodox to think of America as the one country where it is unnecessary to have a past, what is a luxury for the nation as a whole becomes a prime social necessity for the Negro. For him, a group tradition must supply compensation for persecution, and pride of race the antidote for prejudice.”16 Those sentences sound like Locke. He ended with the main conclusions Schomburg had reached after a lifetime of collecting—that the Negro had been a collaborator in his own liberation struggle, that Negroes of talent were typical of Colored peoples, not exceptions, and that the “record of creditable group achievement” was of national and world importance. But Locke strengthened Schomburg’s claim to be modern by emphasizing that the New Negro preferred a “scientific narrative” rather than the older, exclusive, antiquarian chronicle of the Negro’s woes. This helped, because Schomburg was himself an antiquarian, mainly a collector and not an academically trained historian. But Locke valued self-motivated collecting and sifting through one’s history as a sign of the self-conscious intellectual agency of the New Negro and foregrounded Schomburg as a pioneer of that. Again, to visualize that practice, Locke published the photographs of book and manuscript title pages from Schomburg’s collection that made this article fit nicely into the issue’s overall agenda—that to be a New Negro meant to plumb one’s history for a more self-conscious future.

Locke’s transformation of J. A. Rogers’s submission, “Jazz at Home,” had a less positive result. Locke’s moralizing, even condemnatory, tone toward jazz produced an article that was curiously ambivalent about an art form the issue introduced as indicative of the New Negro. “The earliest jazz-makers were the itinerant piano players. … Seated at the piano with a carefree air that a king might envy, their box-back coats flowing over the stool, their Stetsons pulled well over their eyes, and cigars at an angle of forty-five degrees, they would ‘whip the ivories’ to marvelous chords and hidden racy, joyous meanings, evoking the intense delight of their hearers who would smother them at the close with huzzas and whiskey.” While a deft portrait perhaps of Willie “The Lion” Smith, it drips with condescension. “For the Negro himself, jazz is both more and less dangerous than for the white—less in that, he is nervously more in tune with it; more, in that at his average level of economic development his amusement life is more open to the forces of social vice. The cabaret of better type provides a certain Bohemianism for the Negro intellectual, the artist and the well-to-do. But the average thing is too much the substitute for the saloon and the wayside inn.”17

Locke responded to jazz more as a late Victorian than a modernist, who saw jazz as a loud and wild music culture that lacked, from Locke’s perspective, the kind of rigor and reflection crucial to art of value. Jazz was a trick, Locke believed, because it suggested that natural talent, rather than study and perfection, was in control over an instrument. Here, Locke’s ignorance of the rigorous practice schedules of bands kept him from seeing jazz as an intellectual activity. His moralizing analysis confined jazz—indeed music—to second-class status in the Harlem number. Insinuating his own negative moral feeling into the article brought a post-publication response from Rogers. “As to mine, I am much indebted to you for your editorship of it. Nevertheless I am inclined to say in all good nature that there was injected into it a tinge of morality and ‘uplift’ alien to my innermost convictions. For instance after a careful weighing of the matter, I am inclined to think that of the two evils the church and the cabaret, the latter so far as progress of the Negro group is concerned is less of a mental drag. On second thought I have decided, however, that your action is for the best.”18

November and December were slow months of work on the Survey Graphic, in large part because of contributors’ delays in submitting their articles. By December 2, Geddes Smith, the managing editor of the Survey Graphic wrote to Locke that they were still awaiting final versions of six articles. Benjamin Karpman had promised to take another stab at the article on the psychology of the Negro, but soon gave up on it. Another article, by Bruno Lasker, had been received, but Locke and the editors had decided it needed substantial revisions. That still left four articles—Kelly Miller’s on race prejudice, Winthrop Lane’s “Ambushed in the City: The Grim Side of Harlem,” George Haynes’s “The Church and the Negro Spirit,” and Locke’s own revision of his New Negro article—not in hand. When Locke came up on December 12–14 to work on the Survey Graphic the conclusion they all reached was that the issue would again have to be postponed until March. Apart from outstanding articles, the business office had complained it did not have enough time to get out an issue for February. The editors also gave Locke an ultimatum: they needed his final version of the New Negro by the next weekend.

Locke finally turned that in after acceding to the editors’ request to shift away from his social history of Black thought toward a critique of contemporary views of the Negro—an edgier concept buried deeper in the earlier draft. “In the last decade something beyond the watch and guard of statistics has happened in the life of the American Negro and the three norns who have traditionally presided over the Negro problem have a changeling in their laps. The Sociologist, The Philanthropist, the Race-leader are not unaware of the New Negro, but they are at a loss to account for him.” So began the essay in the present, with a critique of the established “authorities on the Negro problem.”19 After struggling with it for several weeks, Locke found a way to change the article from a mostly nationalist statement of Black self-determination to a critical attack on Black and White thinking about the Negro.

The Survey Graphic editors were very pleased with what he had done. Geddes Smith noted to Locke when the managing editor was shaping the essay to fit within the allotted space that “if you will let me say it, I think that for sustained brilliance this essay strikes a note which we don’t often achieve in The Survey, and I am reluctant to fit it to any procrustean bed of space. If you say so then we shall somehow contrive to alter our layout so as to give this article four consecutive pages.”20

Problems nevertheless continued with other contributors. While all the poetry that Locke had selected for the issue had been revised and resubmitted well before Christmas, a blowup with Countee Cullen threatened to remove one of the most important poems in the issue. Back in October, Cullen had let Locke have his poem “Heritage,” the best unpublished poem in the issue. Indeed, Cullen gushingly had told Locke that “you need never beg for any of my work that you desire to use; whatever I have is yours for the asking.”21 But a week later, Cullen was already pulling the poems “For Dunbar” and “For a Mouthy Woman” from the publication, because they had previously been sent to Harper’s. Then, Cullen stated he would pledge “Heritage” exclusively to the Survey Graphic only “if they are willing to pay fifty dollars for it,” because that was the first prize money for the upcoming Opportunity poetry contest, and Cullen was sure that he would win it if he entered it there. Locke knew that $50 was considerably above what the Survey Graphic paid contributors, especially for one poem. He had to find a way to argue for the poem with the Survey Graphic people in order to get as much money as possible for it, while at the same time not discouraging Cullen by revealing immediately that his fee was too high.

Increasing Locke’s leverage was Cullen’s emotional neediness. His October 31 letter confided in Locke, “L.R. was here Wednesday night—until late. I was painfully distressed, and he was very kind. But I am not certain whether it was mere kindness, or what I most desired it to be. It may be cowardly in me, but I am depending upon you to find out for me.”22 This latter confidence referred to Cullen’s belief that, if he could have a secure relationship with a man he loved, his muse would be “invigorated.” This related to the “Heritage” issue, because Cullen’s insistence on the $50 came out of his belief that “I doubt that my muse will supply me with anything else as good for the Opportunity contest.” In one sense, Cullen’s request for assistance in ferreting out whether “L.R.” was in love with Cullen was simply a request from a friend, but Locke may have also felt that he was doing this extra favor to get a break from Cullen on the matter of payment.

At the same time that Locke succeeded in fixing Cullen’s love interest, the editor lobbied the Survey Graphic staff about the importance of “Heritage” to the issue. He arranged to have it featured on two pages in the middle of the issue, with photographs of African art from the Barnes Foundation around it. The importance of this poem to Locke was immeasurable, for it was the poem that best captured the renaissance theme he wished to encourage among the younger poets, by meditating on the meaning of the African past to Black Americans. Perhaps the ambivalence of the poem’s approach to the African heritage led Locke to pass it back to Cullen for revisions. By the end of November, Cullen had had enough of Locke’s suggestions. “Please relinquish me from revising Heritage. Either take it as it is, or give it back to me. I simply cannot do anything with it. I have toiled over it for hours—for your sake—to no end.”23 Of course, Locke took it. And he asked for and received several other poems, some of which he published in the issue.

After submitting the final form to the Survey Graphic on December 9, Cullen asked, “Do you think you can manage to have them pay me before Christmas?”24 By December 20, Cullen was even more insistent: “I hate to trouble you, but unless I receive some money from the Survey people I shall be terribly embarrassed during the holidays. For me to go to Mr. Kellogg does not seem in the best taste, but I shall be forced to do that unless I hear from him by Wednesday morning. I am absolutely without money, and to call on my father would necessitate explanations which I do not care to give.”25 Locke agreed that it would be “unseemly” and wrote Cullen not to communicate with Kellogg. Apparently, Locke had gotten to Kellogg to pay the poets before Christmas, “$40 for Cullen (we are all for using Heritage), $20 for Langston Hughes, and $25 for Claude McKay,” as Kellogg noted on December 19. But when Cullen got his check for $40, he was angry.

“Mr. Cullen called up a bit upset about my letter of yesterday enclosing check for $40,” Kellogg wrote Locke two days before Christmas.

He didn’t think the $40 check should cover the other poems. … I talked with him, saying that my understanding (and I thought yours) was that this was to cover all; but that we didn’t want by any chance to exploit him; that he was quite free to withdraw “Heritage” and enter it in the contest. But that was not his choice. Rather he was for leaving it with us at $40 and leaving it to us what more we could pay for the other poems. I explained what the Survey was; that in our Mexican number the Mexicans contributed gratis; how, as we are under no travel expense this time, we were making modest payments to contributors and what our page rate was. After which I said I thought perhaps we could pay him $10 in addition for such of the other poems as you chose to use. He fell in with that suggestion.26

Kellogg acted in the best interest of the issue by compromising, aware perhaps that as a White magazine, the Survey Graphic might be vulnerable to charges of exploitation if he mishandled this.

Locke was incensed. He believed that Cullen had gone behind his back and undermined his authority. He was right. Locke was not really in charge, and Kellogg was willing to allow an end run to be made by someone purportedly under Locke’s charge. At the same time, had Cullen not circumvented Locke’s position as “middleman,” Cullen would not have received what he had previously stated was his price for “Heritage.” Locke stopped corresponding with Cullen. “I am beginning to fear that you are very angry with me, and I am deeply concerned over your silence. Am I to lose another friend over a trifle?”27 The other friend had been Langston Hughes, who had stopped corresponding with Cullen, according to Rampersad, because Cullen had revealed how intimate Hughes and Locke had been in Paris. Whatever doubt he had about the extent of Locke’s anger was dispelled by Locke’s response. “I have read, and worried over your letter to no slight degree,” Cullen wrote on January 19. “Your language is decisive and beyond misinterpretation; still I will not accept the abrupt termination of a friendship which, from your own admission, has been no less acceptable to you than to me.”28

This incident did not, however, end their relationship. In February, Locke invited Cullen to come to Washington to stay with him. Locke had fallen ill shortly after his letter to Cullen, a sign perhaps that the Cullen relationship meant more to him than he had imagined. It was not that Cullen was a love interest, but Cullen’s potential as an artist helped Locke resist ending the relationship in 1925. Of all of the poets writing in 1925, Cullen was the one most capable of producing consistently beautiful poems that had universal appeal. His themes, of self-destruction, death, and ambivalence of identity also made him modern in a way that McKay was not. His technique was more controlled and finished than that of Hughes, despite the other’s obvious brilliance with folk-inspired poems. Most important, Cullen’s poems reached the universal by working through the emotion of race. To sever a relationship with him would have marginalized Locke and robbed him of influence on the poet who, from the perspective of the day, had the most potential for greatness. Once his anger cooled and his own neediness rose, Locke marshaled the necessary emotional resources to stay connected with Cullen. Although Cullen had exposed the weakness of Locke’s position, it merely revealed what Locke already knew. Cullen had not withdrawn the poem, and the situation had not spilled out into a public controversy. This controversy demonstrated, however, the limits of his control over the publication, apart from the issues of its content.

The Cullen incident was not the only example of how working with the Survey Graphic had its limitations. Early in January 1925, Paul Kellogg proposed that the Survey Graphic host a special dinner as a send-off for the Harlem number. Such a dinner would be a landmark in that “like the number its approach would be the cultural renaissance of which Harlem is the stage; or at least the footlights. What would you think of it? Who would be the speakers? Would it not be possible as at the Du Bois dinner last fall to make it a meeting place for liberals of both races? How could we make it distinctive from that dinner so that it would strike a ringing note—make it another way an[d] avenue for the new Negro expressing himself? Perhaps we could get poets and playwrights and others to contribute as you did at that little Civic Club dinner which set the ball rolling for this number?”29 One problem Kellogg voiced was that they needed to find a draw for the dinner. The obvious choice would be Roland Hayes, whose portrait, Locke would soon learn, would dominate the iconography of the issue. “But we could not of course recompense him,” Locke wrote back enthusiastically. He outlined what he believed would be the choreography of the evening and volunteered to contact Hayes personally to secure his interest if not his participation.

But in February, Kellogg changed his mind. “After some prayer, canvassing the matter in the bosom of the family, and trying it out on a few people representing different points of view, we have decided against attempting a dinner in conjunction with the Harlem number.” There were the normal excuses. “We have ahead of us a number of luncheon and dinner meetings … in the next couple of months. … Also, Opportunity is planning a dinner in connection with their prize contest which will come possibly in April, and while Mr. Johnson was cordiality itself in offering to cooperate with us, still the two dinners would in a sense strike the same note.”30

Even more remarkable than the decision not to hold the dinner was the racial rationale behind Kellogg’s decision. “Aside from these practical considerations, a prejudice factor enters in; and that is, what effect such an inter-racial dinner here in New York might have, especially in the South, on the fortunes of the Survey Graphic as a whole. I hope, even sub-consciously, that this has not been the decisive factor with us. But we don’t want to hamstring our ability to open men’s minds and make for understanding by doing something which might close some of them up like a trap against us.” An interracial dinner might sink the commercial success of the special issue. “If the fact that Negroes and whites sat down to dinner together should overshadow that [the Survey was taking a new approach to race] so far as newspaper publicity goes, what then? The whole thing might be hailed and damned merely as a gesture of social equality; discussion would be thrown back into the old rut; and the new approach would be lost sight of. This might not happen,” Kellogg conceded. “But if it did the dinner would tend to defeat the purpose of the number and dinner alike and throw all the labor that had gone into the number as something affirmative, and nascent, differing from the old protest psychology, off the track.”31

Kellogg’s decision exemplified the failure of American modernism when it came to matters of race. An opening of “men’s minds” to the “cultural renaissance of the Negro” had to be accompanied by an opening of their minds to greater social and political freedom, or the renaissance would be stillborn. Kellogg’s decision also was a personal loss for Locke. At such a party, he could be thanked and praised as the man who deserved credit for advancing the New Negro. Now that would never happen. Perhaps that was fortunate. Given this decision and the logic behind it, he wasn’t key. They had not even asked him to participate in the final discussion as to whether to hold the dinner. He was the odd man out, once again.

But that was the price of working within White modernism in the 1920s. In an ironic way, this was payback for Locke’s elimination of McKay’s “Mulatto” poem from the issue. Locke had cut the poem to make the New Negro more appealing to the White man. It did. But it also let White people off the hook from having to treat Black people equally or be critiqued. Locke quietly accepted Kellogg’s decision. What else could he do? In shifting from Charles Johnson, the Black editor of Opportunity, to Paul Kellogg, the White editor of Survey Graphic Locke had lost the kind of leader who saw interracial commingling around literary success as critical to progress. Of course, Kellogg had to be concerned first of all with his magazine, which, though linked to liberal causes, was, like most Progressive-Era magazines, completely unwilling to challenge segregation. And there was the purely commercial angle. Kellogg had gone out on a limb to devote a huge percentage of its resources, both financial and labor, to a publication about Negroes. He did not want consorting with those Negroes in public to doom his publication.

That Whites felt most comfortable discussing Black issues without challenging their privileged position was again evident when Locke tried to edit the submission of a White contributor. In April 1924, Locke had asked Melville Herskovits to contribute an article on the “dilemma of social patterns” in Harlem, one that balanced “the Negro’s acceptance of the American pattern—the barrier + his effort at duplication,” on the one hand, with the Negro’s internal “demand for a race pattern,” or distinctive way of life, on the other.32 Locke chose Herskovits because he wanted an anthropological rather than a sociological view of Harlem. American anthropology under Boas had pioneered looking at the lives of non-Western peoples as distinct cultural wholes with their own patterns of behavior. But Herskovits and Boas viewed America as one cultural pattern; and when they discussed ethnic and minority diversity in America, they tended to view it sociologically and insist that complete assimilation was the only way for immigrants and other fringe groups to succeed in America. Any failure to do so came close to justifying the arguments of racists that such groups could not assimilate because they were inferior. To his credit, Boas sympathized with the need of Blacks to build racial self-esteem through identification with an African heritage and had lobbied Andrew Carnegie and others to fund research on Africa and to train African Americans as anthropologists. Boas pursued a double enterprise: he encouraged the study of African heritage among Blacks, but argued that assimilation and disappearance of Black identity was the only solution to racism. The contradiction between these two positions was not explicit until the Locke-Herskovits controversy over his Survey Graphic article. Herskovits carried out the logic of the total assimilation argument, without balancing that against the presence of a separate ethnic identity among Black people. When Locke wrote to Herskovits asking him to address the question, “Has the Negro a Unique Social Pattern?” Herskovits instead attacked the notion that a unique racial culture was developing in Harlem.33

After considerable time spent in Harlem, Herskovits had concluded that Harlem was dominated by the same “churches and schools, clubhouses and lodge meeting-places, the library and the newspaper offices and the Y.M.C.A. and busy 135th Street and the hospitals and the social service agencies” of a middle-sized American town. Herskovits went on to attack the notion that a yearning for a separate culture existed among Harlem’s Blacks and used as his evidence the comments of Black writers he had heard at the Opportunity dinner in 1924. “The proudest boast of the modern Negro writer is that he writes of humans, not of Negroes. His literary ideals are not the African folk-tale and conundrum, but the vivid expressionistic style of the day—he seeks to be a writer, not a Negro writer.”34 Herskovits preferred to ascribe any uniqueness in Harlem to regionalism—the remnants of a southern “peasant” culture that migrants had brought with them to the North. Nevertheless, Herskovits did admit in his discussion of the Negro singing of “the spirituals” that they exhibited an “emotional quality in the Negro, which is to be sensed rather than measured, [from which] comes the feeling that, though strongly acculturated to the prevalent pattern of behavior, the Negroes may, at the same time, influence it somewhat eventually through the appeal of that quality.” But he refused to suggest that this quality had any connection to “African culture,” of which he found “not a trace.” He concluded that Negro activity in Harlem was “the same pattern” as Whites, “only a different shade.”35

Herskovits’s ending suggested he was mightily pleased with his essay. Locke was not. He seized on the admission that “the Negroes may, at the same time, influence” the “prevalent pattern” through their performance of the spirituals to suggest editorial changes that would do better justice to the complexity of the Harlem situation. These he sent, through the copyeditor, Geddes Smith, to Herskovits who, according to Smith, did not like the suggested revisions of his article. Herskovits claimed “that we have pushed him to positions which he cannot scientifically accept.”36 In doing so, Herskovits tried to use his position as a “scientist” to upstage and correct Locke, the humanist. Herskovits’s resistance left Locke and the editors with a decision to either accept the article as it was or leave it out—a decision the editors left up to Locke. It was a tricky decision, because it might be politically dangerous to delete the article since Herskovits was an influential White man and a student of Franz Boas, whom Locke wanted to keep as an ally.

Locke decided to keep the article in, but to challenge its assertions in two ways. First, he appended a prefatory note to the article that critiqued its conclusion. “Looked at in its externals,” Locke wrote, “Negro life, as reflected in Harlem registers a ready—almost a feverishly rapid—assimilation of American patterns, what Mr. Herskovits calls ‘complete acculturation.’ Internally, perhaps it is another matter. Does democracy require uniformity? If so, it threatens to be safe, but dull. Social standards must be more or less uniform, but social expressions may be different.”37 Second, Locke took another article by Konrad Bercovici, coupled it with Herskovits’s article, and introduced it in the prefatory note as a “rebuttal” of Herskovits’s article. “In the article which follows this Mr. Bercovici tells of finding, by intuition rather than research, something ‘unique’ in Harlem—back of the external conformity, a race-soul striving for social utterance.” Bercovici observed “an awakened consciousness of race” in Harlem. “Backs are straightened out and heads are raised. Eyes look to their own level when they seek those of other people.” Bercovici had toured the South, had witnessed postures of subservience associated with the Old Negro—the bent back, downcast eyes—developed because of violent enforcement of southern racial etiquette, and could see the northern New Negro posture’s rejection of that pose. Bercovici’s insight challenged Herskovits’s claim that “they face much the same problems as those [other, immigrant] groups face,” which ignored the specificity of southern racism and its unique impact on African American life and culture. Even more subtly, Bercovici noted, “I listened to the preachers in the churches of Harlem. I understood the language. But was there not something unsaid in the preachment? Was the preacher, the minister, not fashioning another God for himself and for his congregation while he spoke?” Here Bercovici confirmed Locke’s sense that intuition could pick up that a unique system of meaning, style, and identity formation operated in Harlem beneath the radar of most White observers, even Columbia University–trained social scientists.38

Bercovici sensed Locke’s argument that if the Negro aspired to nothing more than assimilation, there was really nothing transformative in the Harlems of America. “The feeling,” Bercovici wrote, “is still one of being better than thou, but underneath that, it seemed to me, there was a striving for another culture that was not an imitative one.” Further, he caught the distinction that “they are not inferiors. They do not have to strive for equality. They are different. Emphasizing that difference in their lives, in their culture, is what will give them and what should give them their value.”39 This “value” was part of the reason that Locke took the position he did against Herskovits. The Black community needed to be interested in forging a life that did more than simply imitate White middle-class life or there was no further purpose to the movement.

Remarkably, Locke’s disagreement with Herskovits over his article did not end their relationship, but instead eventually transformed Herskovits’s intellectual position on African American culture. Locke even facilitated Herskovits conducting research at Howard University. All the while he continued to pepper Herskovits with articles and insights about the uniqueness of African American culture and the possible role of African culture in fashioning that New World particularity. Intellectual historian Walter A. Jackson credits Herskovits’s interaction with Locke and other Black intellectuals during the late 1920s as converting Herskovits to his mature position that African survivals existed in American Negro culture and made it distinctive from the rest of American culture. One can go even further and suggest that Locke’s critique, and Herskovits’s openness to it, laid the groundwork for a revolution in anthropological thinking within the United States for it showed that anthropology as a science had to change in order to study racial diversity within modern society by abandoning the sociological model of assimilation and accepting the philosophical concept of cultural pluralism.

Locke’s reaction to this power struggle with Herskovits and to the conflict with Cullen suggested growth on his part. Previously, Locke separated from people with whom he experienced painful or divisive conflict. Perhaps because he so loved managing a major publishing project, his ego was stronger, and he was able to remain involved with those who challenged his authority. His greater emotional flexibility may also have derived from the social dynamics of the Survey Graphic project. Despite differences of opinion on particular issues, the creative space of the Survey Graphic project enabled collaboration between him and the staff, even when their understandings of the race and ideological issues involved diverged. In that give and take, sometimes it was Locke who influenced a White intellectual, as in the case of Herskovits. At others, it was the staff at Survey Graphic who pushed Locke in a new direction from that which he would normally take.

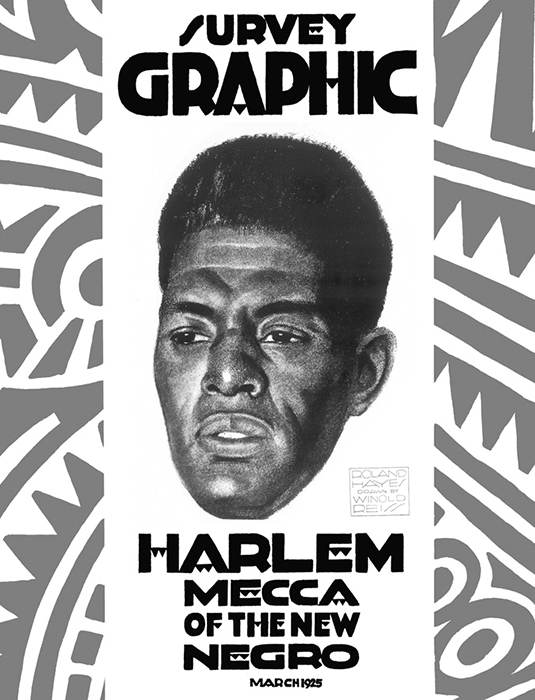

A good example came with the debate over the cover to the number. Only weeks before the issue was to go to press, Paul Kellogg wired Locke a telegram for his approval to change the cover. “Sales and advertising experts say we can double sales of Harlem number if we use Reis[s’s] marvelous head [of] Roland Hayes on Cover, [and] also inside. More sales more educational reach. More-over Hayes personifies youth[,] racial genius[,] New Negro as nothing else. Please wire him urging him grant this permission.”40 The original cover included broad blue borders of Reiss’s modernist abstract pattern of gears, parallel lines, and circles that evoked both industrial machinery and African motifs, American art deco and primitivism. In the middle a White area served to background the title of the cover printed in bold letters. It was a nice but not startling design. Kellogg’s suggestion, while economically driven, would result in the boldest cover of an American magazine to date.

Locke responded quickly that he did not like the idea, because the portrait and the design clashed. Kellogg was away when Locke’s letter arrived, and in his absence, the editorial staff somehow concluded that he was leaving the decision up to Locke. One of the editorial assistants, Miss Merrill, sent Locke an engraver’s proof of Hayes’s portrait for his evaluation, and Locke continued to object to the combination. But Locke weakened his position by writing Kellogg that the final decision should be left up to Hayes, who would be forever associated with the issue. As was the case in the controversy over the “Mulatto” poem, Locke abdicated total responsibility for the decision, perhaps because he thought that Hayes would veto the idea or because he knew the decision would not rest on his opinion in the final analysis. But shifting the responsibility for the final approval to Hayes gave Kellogg the out they needed, for if Hayes gave his approval, they could go ahead.

While they awaited his decision, Kellogg continued to lobby Locke about the benefits of the new cover. “There is a lift, a lilt, a spirit to the portrait of Hayes which visualizes the gleam, which you have put into this cluster of manuscripts so admirably. It tells more than many words of the spirit of the thing.”41 Locke remained unconvinced and argued for a redesign if the portrait was used. In the end, Locke’s objections were pointless, because Kellogg received a telegram from Hayes giving them a free hand and Kellogg decided to go with the bold design.

Locke’s taste had failed him here. The cover and portrait clashed, but that clashing was the essence of modernism. Reiss’s border mix of industrial and African design elements framed Hayes’s head, situating African Americans in a new context—that of the urban, industrial civilization that African Americans entered through the Great Migration and owned because they brought their culture with them. The surrounding abstract design evoked a modern age of gear teeth and machinery. And Hayes’s uplifting head with light shining on it from below anointed the Negro with a spiritual confidence that said, “We are unfazed by the challenge of such a new arena of struggle.” More subtly, the jagged edges of the border suggested that the new urban context threatened as well as supported the New Negro, the cover nicely evoking the tension of the New Negro formulation, its promise and its dangers. The cover has endured as a symbol of the dynamic uncertainty of the New Negro moment in the mid-1920s.

Locke had lost another battle over control of the issue. But he probably did not fret over it, because the final decision had never been in his hands. That was also evident in another case where he wanted Reiss’s abstract design “Dawn over Harlem” as the frontispiece of the issue. The Survey Graphic staff overruled that decision, because of their feeling that it was too modernistic to begin the issue. Kellogg’s skill at magazine composition was surer than Locke’s, obviously. Given that they had decided to put Hayes’s head on the cover, it made sense to repeat that powerful symbol, without the modernist halo, inside because it was now the most powerful symbol of the New Negro. Having it on the cover and as the frontispiece created a rhythm that lifted the Reiss portraits from being illustrations to texts that drove the issue. In a sense, the prominence of the portraits and the designs switched the usual hierarchy of print and image in most Black magazines of the period.

Locke’s voice, however, had not been ignored, simply overruled. And Locke seemed to have the self-knowledge and common sense not to challenge that position. After all, in countless other ways his insights were utilized throughout the Survey Graphic. A key example came shortly after the cover debate when Du Bois, perhaps realizing the growing significance of the Survey Graphic project and its documentation of Negro intelligentsia, decided to sit for a Reiss portrait. This coincided with Dr. Moton’s decision also to sit for Reiss. By February 12, Kellogg was eyeing the commercial advantages of having these two portraits in the issue. “So far as the general public goes, it of course would have been a fine stroke to have included these two portraits in the issue. But from the standpoint of the cultural front and the new approach of the issue, Hayes and Robeson were far more appropriate.” Still, Kellogg wondered whether they might still “include one or both of them. What would you think?”42 There was also the added pressure that Moton had called up the Survey Graphic and complained that the Hampton-Tuskegee nexus of Negro education had been left out of the issue.

Front cover, Survey Graphic, March 1, 1925. Reproduction courtesy of Black Classic Press.

Here Locke put his foot down. “Let’s leave them out of this issue,” he wrote on February 17. “There is no use bringing in through the back-door what we have so ceremoniously bowed out of the front. You see their very names raise the issue. Moton is in the heat of the Tuskegee-Hampton campaign with more hat-in-hand arguments than ever. Indeed he would be publicly embarrassed with our platform. Let’s just stick to our original plan and put it over big.” Kellogg agreed “that we ought to stick to our original last—a fresh one—and I have been staving off the pressure of the philanthropic-economic-education group who thought we were neglecting them.”43

When the issue finally did appear on March 1, 1925, it was a stunning success. Some have claimed that the Harlem issue’s popularity was largely due to advance purchase of copies by philanthropists. The Survey Graphic records tell a different story. While Albert Barnes ordered one thousand copies to distribute personally in Philadelphia, George Foster Peabody ordered one thousand copies to be sent out to his friends in the United States and abroad, and Amy and Joel Spingarn ordered another one thousand for Locke to distribute to Negro schools and universities, by the time those copies had been delivered, the first edition of twelve thousand copies had sold out. The Survey Graphic ordered second and third editions of twelve thousand copies each, and within two more months those were sold out. More than forty thousand copies were sold in the final tally, making it the largest sales ever for a Survey Graphic issue. The Survey Graphic received record numbers of requests for new subscriptions as a result of the Harlem number as well.

The Harlem number benefited from great timing, arriving on newsstands just in time to give a newly awakened public the most comprehensive introduction to the movement available. It caught the movement on its ascendance and accelerated it because of Locke’s redefinition of the New Negro as a discursive sign of the future, an as-yet-unfinished subject that the readers of the magazine themselves could participate in constructing.

Also critical to its success was the collaboration between Locke and Kellogg. Locke had achieved something here that was unprecedented—to get a White mainstream journal to create the most powerful representation to date of Negro expression. The interaction among Locke, Kellogg, Reiss, and the staff, as well as the poets, sociologists, short-story writers and anthropologists, self-taught historians and degreed scholars was unique in American magazine history and resulted in an issue above and beyond what they could have done without that collaboration. The Harlem issue nicely embodied the central argument of the issue—that something transcendently beautiful emerged out of diversity, especially a diversity that went beyond simply the racial.

Perhaps, most remarkably, the issue seemed to speak to different, segregated audiences and elicit awe from almost all who picked it up and read it. Black people felt that it spoke for them, without committing them to any fixed position, by suggesting their untapped potential and Beauty. It reached a younger reading public that wanted a message of hope and possibility in a new century. By allowing the poetry, essays, and articles to be authored by Negroes, Kellogg allowed the voice of the New Negro to be expressed in a way that made a mainstream journal Black—if only temporarily. Indeed, Kellogg allowing Locke to foreground poetry and art in the issue reinforced the notion that what was important was the Negro voice, not the objectification of the Negro as a Negro problem. That resonated with White liberals and made the Survey Graphic hip in a way it had never been before.

And then Winold Reiss’s pastel portraits and abstract designs translated the mood Locke wanted to communicate in the poetry and essays into something of powerful visual impact. The Reiss portraits translated “Negroness” into graphically intense and beautiful Italian Renaissance–like images of real people. African American eyes feasted on his portraits because nowhere could one find Black people visually represented as they appeared naturally. Like Life magazine, Vanity Fair, and dozens of other exciting picture magazines of the 1920s, the Harlem issue put the images up front and gave sympathetic or merely curious readers something they could engage without actually having to read it.

Here the cover was the key—a bold representation of the Negro as modern without equal in American publishing. Just carrying the Harlem number into a room drew attention to this bold Black face framed by a blue and white modern design. It was ironic that the Survey Graphic advertising people had forced Locke and the other editors to approve putting the face of a Negro on the cover for economic reasons. They were proved right, but American magazine editors subsequently have justified the paucity of Black people on covers with the homily that they would not sell to a predominantly White magazine-reading public. In the 1920s, the Negro was not only “finding beauty in oneself,” but a significant portion of the American public also found beauty in the Negro. The Harlem number of the Survey Graphic gave a visually starved American public something visually satisfying about the Negro to look at. They continued to look and read in record numbers. Locke was again an American celebrity.