28

Beauty or Propaganda?

Sometime in the late 1920s or the early 1930s, Alain Locke and W. E. B. Du Bois entered a basement restaurant in Black Washington, D.C., where the future Black psychiatrist Charles Prudhomme was working as a waiter, and sat down for dinner. Each requested a glass of boiling water. Once the glasses arrived, Locke and Du Bois picked up their silverware and placed them in the boiling water.1 That gesture reflected their opinion that Negro restaurants did not maintain the highest standards of cleanliness. Their concern for cleanliness was not unique. Booker T. Washington, more than a quarter of a century before, had made cleanliness the centerpiece of the civilizing mission of Tuskegee Institute.2 Cleanliness not only anchored personal hygiene but also symbolized what Washington wanted instilled in the minds of ex-slaves—that their bodies, their selves, were worth preserving, worth investing in for the future, through self-care.

That Locke and Du Bois made such a gesture of self-protection suggests they doubted Washington’s ethic of cleanliness had been adopted widely by the Black establishments that Jim Crow segregation forced them to eat in. Working-class, even entrepreneurial African Americans, had not yet, in the language of Washington, thrown off the negative conception of themselves that led them to maintain less than sterling standards of cleanliness in their restaurants. As these three-piece-suit wearing Europhile academics sat down in this modest Washington restaurant, Locke and Du Bois felt a sanitary gulf separated them from most other African Americans in the 1920s and 1930s. There was still work to be done, and their gesture suggests that all three men agreed on at least one thing—that art, science, business, politics, all education, really, had a dual purpose—to instill civilization in an uneducated people and to purify them, like those utensils, of the self-hate acquired in their sojourn in America. Indeed, so fatalistic was Locke about this process, it’s a wonder he risked such a meal in a “Colored” establishment at all. Of the three, Locke was the extreme mysophobe, who often refused to shake hands, touch doorknobs, or otherwise make physical contact with dirt. Usually, instead of visiting such restaurants, Locke took his meals at Union Station, its restaurant the only “White” restaurant in Washington, D.C., that allowed Black people to dine in, since it was a federal facility. Locke too might need “purifying” of some of his accommodations to a White supremacist world.

Nevertheless, Locke had decided to join Du Bois for a dinner in the Black community on this occasion. With the smells of chicken frying, ribs boiling, and okra steaming filling the air around them, they talked for several hours. Prudhomme could not catch the conversation. But if it was in the late 1920s, it might very well have been on the subject on which both held strong and opposing opinions—the question of Black art and its role in the crisis of the Negro people. What was the goal of African American creative expression? Was it to defend Negroes against racism? Or uncover Beauty, especially among a people often thought of as lacking in Beauty? Later, Locke would pose this conflict of aspirations as a question of what the Negro wanted: “Art or Propaganda?”

Why was this an issue between two Harvard-educated Black intellectuals who agreed on much, such as the level of protection they needed from the lack of cleanliness in Black restaurants? Of course, both Locke and Du Bois believed in “art.” Du Bois had defended the rights of artistic freedom for artists before the mid-1920s against “philistines” who tried to limit Negro artistic freedom. But when The New Negro was published in 1925, Du Bois reacted differently, for Locke went so far as to dethrone propaganda as the reigning raison d’être for Negro art and suggest that beauty was its highest goal. In his otherwise appreciative review in the Crisis in January 1926, Du Bois cautioned:

With one point alone do I differ with the Editor. Mr. Locke has newly been seized with the idea that Beauty rather than Propaganda should be the object of Negro literature and art. His book proves the falseness of this thesis. This is a book filled and bursting with propaganda but it is propaganda for the most part beautifully and painstakingly done; and it is a grave question if ever in this world in any renaissance there can be a search for disembodied beauty which is not really a passionate effort to do something tangible, accompanied and illumined and made holy by the vision of eternal beauty. Of course this involves a controversy as old as the world and much too transcendental for practical purposes, and yet, if Mr. Locke’s thesis is insisted on too much it is going to turn the Negro Renaissance into decadence. It is the fight for Life and Liberty that is giving birth to Negro literature and art today and when, turning from this fight or ignoring it, the young Negro tries to do pretty things or things that catch the passing fancy of the really unimportant critics and publishers about him, he will find that he has killed the soul of Beauty in his Art.3

Here was the most significant challenge to The New Negro Locke had to deal with in 1926 and 1927. While Locke had been extremely inclusive in The New Negro so as not to offend any established institutional gods of Negro America, Du Bois had sniffed out that the volume made Locke and his Negro aesthetic philosophy a threat to the Du Boisian view that Negro art was meaningful only as part of the political struggle for Negro freedom. Indeed, The New Negro displaced the NAACP agenda of protest art with a generational permission for Black artists to see themselves as artists first. “The elder generation,” Locke wrote, “of Negro writers expressed itself in cautious moralism. … They felt art must fight social battles and compensate social wrongs. … The newer motive, then, in being racial is to be so purely for the sake of art.”4

The phrase “for the sake of art” conjured for Du Bois the “art for art’s sake” movement of late nineteenth-century Europe. One of its chief proponents, Walter Pater, narrated how humanity’s authentic search for beauty culminated in a rejection of conventional morality—and conventional notions of social responsibility. Unlike Locke, Du Bois possessed a moralizing view of aesthetics: like Matthew Arnold, he believed the arts taught traditional moral values, and when they did not, they eroded those values, which led to decadence and sexual deviance. Protest art was, in fact, a kind of moral art, and Beauty was not so much an end, but a means to restoration of Black humanity. Locke’s “Negro Youth Speaks” suggested the younger generation did not want to shoulder that burden, but to create art that might or might not advance the progressive race struggle. Locke believed protest art narrowed Black identity to always responding to White racism. For Locke, Negro subjectivity was richer and more various than anti-racism. To insist that all Negro artists be soldiers in a war against White racism denied them the right to be self-reflexive and human.

There was another issue between them: sex. A Negro art movement based on Beauty was a slippery slope to decadence and homosexuality, and Du Bois was having none of it. Although Du Bois engaged in serial adultery, that did not make him tolerant of prostitution, gambling, thugs, or homosexuality. When he discovered that his business manager had been arrested for same-sex soliciting in a public place, Du Bois fired him, although later he admitted that had been a mistake. Du Bois feared unleashed sexual desire as the defining identity of the Negro Renaissance. Locke, by contrast, had already come to terms with himself as an “Immoralist.” To have a sexual life and continue to assert his right to be considered a “respectable Negro” required him to get past an impasse to self-representation that Du Bois still struggled with. Locke saw the Black Victorian tradition of self-control as part of the problem of the educated Negro and also part of his own problem with creative expression. Often he lamented that he was too “tightly wound” to allow his spirit to soar as a writer. In that sense, his view of the Renaissance resonated with Du Bois’s, but arrived at a different conclusion. The Negro Renaissance was a loosening of sexual restraint, and that was a good thing. In that sense, he could be sympathetic to the desire for freedom among the young artists, even if he wanted them to do something more with it than simply celebrate their libido.

Du Bois’s reaction to the new art shows the difference between him and Locke, just as the dipping of silverware in hot water shows their similarity. Du Bois was the Anglo-American, who saw art as an instrument of morality and social change in a manner not too removed from the attitude of Matthew Arnold. Culture should educate whether moralistically or racially. Locke, however, was the European, who saw art as the highest product of civilization, to be revered for its own sake, and to be loved like sex. Du Bois saw art as of instrumental value in changing American racial practice; Locke extolled art as the eternal search for the Beautiful. Du Bois was the Black Victorian, whose rigid sense of the private and the public fueled his anger over how informal “at home” images of Negroes were projected by the American media as the public identity of the Negro. Locke was the Black Edwardian, who though horrified by how newspapers and some literature depicted Blacks, was also alienated by the provincial, heterosexist, middle-class narrative that dominated literature written by Du Bois, Jessie Fauset, and others like him.

Both Locke and Du Bois did eventually agree in later years that the Negro Renaissance declined into decadence and wallowed in homosexual allusions. But Locke claimed those were not his explicit goals for the New Negro Renaissance. His movement did not exclude homosexuality, but was more a declaration of freedom, that Negroes had the right to pursue art, as the ancients had, in the search for Beauty as part of the Negro being human. If African Americans sacrificed that to the racists, the result, Locke argued, would be not only inferior art but also the sacrifice of freedom and humanity.

Another question looms: were Du Bois and Locke talking about art or Locke’s dismissal from Howard when they visited that restaurant? Given that Prudhomme could not recall the exact period of the visit, might it had occurred when Locke was still unemployed? Or if later, might they have been discussing the continuing problems of Negro scholars in Negro higher education, something Du Bois was concerned about for the rest of his career? Unlike Locke, Du Bois seemed always to land on his feet, whether it was leaving Atlanta University in 1910 to take the editorship of the Crisis at the NAACP or leaving the NAACP in 1934 after his dispute with its board and rejoining Atlanta University as a professor. But not one major Black institution had come forward to offer Locke a job after he was fired from Howard. Of course, Locke was not as eminent a Black intellectual as Du Bois; but arguably, he was the next after him. Neither the NAACP nor the Urban League welcomed the second-best-educated Negro in America into its operations. No Black journal or newspaper made him an editor, even though he had proven himself an exceptional editor of Opportunity, the Harlem number of the Survey Graphic, and The New Negro. But some of Locke’s negatives were positives. “Howard has tried to hurt you,” Hazel Harrison, a pianist and friend of Locke’s, noted. “But they have actually pushed you forward. Many people who would not have known of you otherwise are talking about you and reading everything you write.”5

Locke’s dismissal had freed him to write more, lecture more, and nationalize his identity. It also enabled him to identify more with artists, most of whom also lacked institutional moorings. Locke knew that if he was to remain in the public eye, he would have to out-produce and outmaneuver other interpreters of the New Negro, men such as Walter White, Charles S. Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, George Schuyler, Carl Van Vechten, H. L. Mencken, and V. F. Calverton, and, of course, Du Bois, who enjoyed connections with institutions or publishers he lacked. To do so Locke anointed himself the “godfather” of the movement and took upon himself the responsibility to watch over the movement, to advance its artists, to define its goals, and to defend it from attacks. Locke threw himself into advocacy work so that no one could ignore him. The role gave him enormous energy. Without the distraction of teaching, Locke flooded the market with essays and articles that defined Negro Cultural Studies for the 1920s. He might sit down to dinner with Du Bois. But afterward, he would be up and running to get the next article in print or deliver the next speech to a paying crowd.

Locke wrote sympathetic, encouraging reviews of writers’ first books, such as Countee Cullen’s first book of poems, Color, in the January 1926 Opportunity. “Ladies and gentlemen! A genius!” Cullen was a great Negro poet because he possessed the “lyric gift” and wrote about universal subject matter as a Black man. “Pour into the vat all the Tennyson, Swinburne, Housman, Patmore, Teasdale you want, and add a dash of Pope for this strange modern skill of sparkling couplets,—and all these I daresay have been intellectually culled and added to the brew, and still there is another evident ingredient, fruit of the Negro inheritance and experience, that has stored up the tropic sun and ripened under the storm and stress of the American transplanting.”6 Some critics of The New Negro chided Locke for this kind of praise of new and untested poets whom Leon Whipple called average American writers. But Locke saw in Cullen a Negro talent surveying the field of human experience and giving it a spin that only Black youth could provide. Even when Cullen focused on the Negro predicament, he treated it with a freedom and subtlety lacking in others. “The paradoxes of Negro life and feeling that have been sad and plaintive and whimsical in the age of Dunbar and that were rhetorical and troubled, vibrant and accusatory with the Johnsons and MacKay [sic] now glow and shine and sing in this poetry of the youngest generation.”7

In contrast to James Weldon Johnson, Locke also advanced Negro art as something more than Negro writers. Early in 1926, Locke wrote “The Negro Poets of the United States,” for William Braithwaite’s Anthology of American Verse, and made a distinction he returned to throughout the decade. “Negro poets and Negro poetry are two quite different things. Of the one, since Phyllis Wheatley, we have had a century and a half; of the other, since Dunbar, scarcely a generation. But the signification of the work of Negro poets will more and more be seen and valued retrospectively as the medium through which a poetry of Negro life and experience has gradually become possible.”8 In making Dunbar the beginning of the tradition of Negro poetry, Locke broke with Johnson, who had argued that contemporary Negro poetry was defined by its rejection of Dunbar and the twin emotions of humor and pathos in his poetry. Locke also distinguished himself from Du Bois, who evaluated literature in terms of its pragmatic utility in a war of representation with White racism. Locke announced that Negro art was a Black tradition of forms that existed even when Whites and race conflict were absent. The poetry of Dunbar showed that a Black voice transcended victimization and, when it did confront victimization, did so with irony, humor, and wisdom that short-circuited the dehumanization of racist discourses. To write poetry, Locke declared in 1926, meant to come out from under the shackle of racist discourses and write like a Black person whose experience was as rich and complex and rewarding as that of any other American’s. His job was to sell the notion that one could write as a Black man or woman and say something compelling to all readers.

By February 1926, however, Du Bois could no longer suppress his critical feelings and extended his reservations about the philosophy of Beauty in The New Negro: An Interpretation into a “Symposium” in the Crisis that ran from February to July 1926. It was an extraordinary gesture, for it transformed Du Bois’s reservations into a set of essays on the role of art in the representation of the Negro in American culture. Did writers, Black or White, and publishers, have an obligation to be representative, that is, to produce literature that not only embodied the literary taste of the day for stories and poems about working- and criminal-class urban culture but also told stories rooted in the lives of middle-class, stable, outwardly moral Black people? Was the popularity of certain characterizations of Negroes as criminals, pimps, and loose women not designed to discredit moral Black people? Was the willingness of publishers to disseminate stories with such characters and not those of moralistic middle-class Blacks a conspiracy to impede Black acceptance into the nation’s mainstream? These questions not only had merit, they had weight.

Unfortunately for Du Bois, most of the contributors who wrote in to answer his questions rejected his position. Most thought the greater danger was censorship, especially self-censorship. Carl Van Vechten, whose racy novel, Nigger Heaven, would be published later that year, argued that the main consequence of Du Bois’s analysis was that it “might be effective in preventing many excellent Negro writers from speaking any truth which might be considered unpleasant.”9 DuBose Heyward, whose Porgy Du Bois referenced, responded that such middle-class lives “must be treated artistically. It destroys itself as soon as it is made a vehicle for propaganda.”10 Writer after writer responded that they valued their freedom over Du Bois’s notion of their responsibility to the Negro—or any other—public. Almost all of the younger Negro writers, even those friendly to Du Bois, such as Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes, voted for the freedom of the artist and issued a truism: the artist should write what she or he felt. Most believed there was little causality between what they wrote and the actions of the larger, presumably White, community on racial issues. Among the young male writers, only Cullen agreed with Du Bois that a need existed for literary types that were “truly representative of us as a people,” but even he admitted that he could not really endorse the “infringement of artistic freedom.” The consensus was Du Bois was far out of step with contemporary writers, who found his critiques implausible.

But Du Bois had identified a real issue. The charge that the American media encouraged images of “twelve million Americans as prostitutes, thieves and fools” had merit. The history of Black minstrelsy suggested that White audiences of popular theater demanded Black actors perform caricatures of themselves. African Americans grew up in the early twentieth century bombarded with degrading and dehumanizing images in the popular press. Even Locke’s Harlem issue of the Survey Graphic documented the impact of the racist discourse when Elise McDougald wrote that the Negro woman “realizes that the ideals of beauty, built up in the fine arts, exclude her almost entirely. Instead, the grotesque Aunt Jemimas of the street-car advertisements proclaim only an ability to serve, without grace or loveliness. Nor does the drama catch her finest spirit. She is most often used to provoke the mirthless laugh of ridicule; or to portray feminine viciousness or vulgarity not peculiar to Negroes. This is the shadow over her.”11 McDougald had documented how American advertising capitalism had fixed a racialized stereotype of servile labor into the minds of upwardly mobile American Whites without them being aware of it. Du Bois had perceived that art was class and racial advertisement and a weapon to redress the cultural if not the economic imbalance in America’s representation of the Negro. But Locke believed one had to resist the temptation to utilize art in the same way as the oppressor did, because to do so reduced one’s humanity to the low level of one’s enemy.

Just as profound, Locke and Du Bois differed over the nature of racism and how racial images functioned in America. In a Modern Quarterly article, “The Social Origins of American Negro Art,” Du Bois argued that negative racial images in American literature reinforced and sustained American racial practices. Published in October 1925, the article argued the constant and unrelenting dissemination of negative images of Black people by American literature forced the Negro American writer to counter this “propaganda” with a counter-hegemonic literature. Racism, in other words, was propelled by an overwhelmingly racist American literature. Ever competitive, Locke answered Du Bois’s argument in a Modern Quarterly article of his own soon afterward, “The American Literary Tradition and the Negro,” where he argued American literature had not always disseminated wholly negative images of Black people. Applying his Marxian analysis of Race Contacts to American literature, Locke argued that the literary image of the Negro followed social practice toward the Negro, and changed over time in relation to the changing social and economic position of the Negro in American life. A docile Negro image, for example, had dominated when an economically thriving antebellum slavery regime needed to convince outside critics that Blacks were satisfied with slavery. After Reconstruction, when the ruling class of the South needed to discipline ex-slaves to work in the sharecropping regime, southern literature disseminated the image of the Negro as the animalistic brute, who was a threat to the social order and needed to be kept in line by the KKK. For Du Bois, race was a static, permanent phenomenon, while for Locke, it was fluid, varying in relation to changes in the demographic and economic calculus of American society. For Locke, the changeableness of the image of the Negro in literature showed that art was less of a propaganda tool and more of a barometer of race relations. The current New Negro image reflected a flexibility in the position of Negroes in modern American society being tapped by contemporary modernist Negro writers.

The art is propaganda argument was, in reality, a demand by Du Bois to constrain the Black literary awakening to producing positive, bourgeois images of the Negro to counter the debased representations emanating from racist American popular culture. He wanted Negro literature to generate more images of Black people as moral exemplars with a complexity all but absent from an American public imagery that confined Negro representation, usually, to negative, that is, lower-class, images of Blacks. Du Bois’s problem was that serious American literature of the 1920s was decidedly anti-bourgeois. Such White writers as Sinclair Lewis and Sherwood Anderson depicted the middle class as buffoons, if not worse, and young Black writers would have marginalized themselves in American literature had they followed Du Bois’s advice.

At root, Du Bois’s argument was about sex. A notorious paramour, who sustained hot, sexually prolific relationships with dozens of women, such as Georgia Douglas Johnson and Jessie Fauset, while married, Du Bois was himself in the closet, unwilling to publicly support a literature movement that foregrounded sexual desire in its representation of the Negro. Added to this heterosexist contradiction was the homosexual one for Du Bois: he fired his business officer, Augustus Granville after Du Bois discovered he had been arrested for public solicitation. Later, Du Bois said he regretted it. But the message was clear: in an ideological war between the races, Du Bois could not afford to allow the reputation of that race, and the Crisis, to be damaged by public homosexual scandal.12

Du Bois’s moralizing stand, therefore, helped Locke to advance himself as the writers’ advocate, and the older man’s critique of White publishers and playwrights created an opening for Locke to write for those White journals and launch a new argument that the most fertile field for the Negro Renaissance was in an integrated world of culture.

Even more, Locke exploited opportunities for magazine writing in fields ignored by Du Bois—art, music, and the theater—eager for articles on the implications of the Negro Renaissance. The field of Negro drama was particularly fertile and Locke published his first article on the Negro drama in a mainstream journal when “The Negro and the American Stage” appeared in the February issue of Theatre Arts Monthly. That article began a twenty-year association with its editor, Mrs. Edith Isaacs, whom Locke may have met through Paul Kellogg. That article also shifted his earlier emphasis from Negro playwrights to Negro actors as the most important element in contemporary Negro dramatic performance. Prior to this article, Locke had advocated that the Negro drama should be based in Negro universities, written by Negro playwrights, and acted by Negro actors. But in the year since the publication of “Max Rheinhardt Reads the Negro’s Dramatic Horoscope,” Locke embraced his analysis. “Welcome then as is the emergence of the Negro playwright and the drama of Negro life, the promise of the most vital contribution of our race to the theatre lies, in my opinion, in the deep and unemancipated resources of the Negro actor, and the folk arts of which he is as yet only a kind and hampered exponent.”13

Having to survive in the literary marketplace without a university job helped Locke make an ideological shift—away from a nationalist notion of Black art as only appropriate in Black institutions to a notion of Black art as a kind of Trojan Horse intervention in White cultural spaces. His article also acknowledged that Black actors—Paul Robeson, Charles Gilpin, Rose McClendon, Opal Cooper, Inez Clough, Bert Williams, Florence Mills, Bill Robinson, Josephine Baker, Ethel Waters, and Abbie Mitchell—were having a bigger and more transformative impact on the American theater than was the African American playwright. He now made another logical leap: the ultimate value of a Negro drama would be to transform the American theater through dissemination of its “technical idioms and resources of the entire theatre” than in the segregated theater. Was Locke’s optimism justified? Yes. Negro actors would transform by their performance plays written by White playwrights. Charles Gilpin, Locke’s favorite as Brutus Jones, had transformed Emperor Jones into a cerebral tour de force of a Black madman and given it an intellectual intensity absent from Eugene O’Neill’s script. Most famously, actors in Porgy lifted a play of low life into a universal tragedy by their talent. Part of the reason was race: such performers as Leontyne Price starred in Porgy at a time when it was not possible for her to appear in an opera in America. Part of the reason was form: Black actors brought a technical facility to the performance of even flawed plays that lifted American drama onto a plane with the best of world drama.

In another article, “The Drama of Negro Life,” in the October 1926 issue of Theatre Arts Monthly, Locke cleared a space for White participation in the New Negro movement. “A few illuminating plays, beginning with Edward Sheldon’s Nigger and culminating for the present in O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings, have already thrown into relief the higher possibilities of the Negro problem play. Similarly, beginning with Ridgeley Torrence’s Three Plays for a Negro Theatre and culminating in Emperor Jones and The No ’Count Boy, realistic study of Negro folk-life and character has been begun, and with it the inauguration of the artistic Negro play.”14 While Locke continued to hope and work for the development of the Negro playwright and the Negro Theater, “the pioneer efforts have not always been those of the Negro playwright and in the list of the most noteworthy exponents of Negro drama, Sheldon, Torrence, O’Neill, Howard Culbertson, Paul Green, Burghardt Du Bois, Angelina Grimke, and Willis Richardson, only the last three are Negroes.”15

Locke also used this article to begin his long answer to Du Bois’s argument in the “Symposium” that Negro literature ought to provide answers to the charges of racists. “Propaganda, pro-Negro as well as anti-Negro, has scotched the dramatic potentialities of the subject. Especially for the few Negro playwrights has the propaganda motive worked havoc. In addition to the handicap of being out of actual touch with the theatre, they have had the dramatic motive deflected at its source. Race drama has appeared to them a matter of race vindication, and pathetically they have pushed forward their moralistic allegories or melodramatic protests as dramatic correctives and antidotes for race prejudice.” Where Du Bois identified White playwrights as the enemy of a true Negro portrait, Locke argued White authors had written some of the most successful race problem plays of recent times. Their plays had succeeded because the race problem was, in some respects, the White man’s problem. Willis Richardson had excelled so far at writing an alternative drama—a Negro “folk-drama” that would “grow in its own soil and cultivate its own intrinsic elements,” as Dunbar’s poetry had done. Locke preferred to see this interior view of Negro life on the stage. But both White and Black playwrights were co-constructing New Negro drama, drawing on their different strengths.

Locke held back from making the leap implied by his new approach to the Negro drama. If being a New Negro was only an attitude and a commitment to a beautiful portrayal of the Negro experience, then a White playwright was potentially as much a New Negro as a Black playwright or actor. The White artist acknowledged that there was something about the Negro experience that he needed to complete his identity as an American, whereas the Black actor in a White-authored play dialogued with the White side of his identity and in doing so reformulated African American identity. Locke was still a race man, though the trajectory of his articles and introductions redefined the Negro drama as an interracial dialogue. Locke was resurrecting Du Bois’s earlier, more complicated notion of Negro identity, “double consciousness,” as potentially a positive, not a debilitating divided self, but a dialogic American. The Negro drama must become a means of revelation and reconciliation of the two sides of Negro/American identity.

By 1926, Locke was acknowledging that if a Black impresario wanted a Negro drama to flourish, Negro drama needed White patronage, not to rely on Black colleges and universities. Locke’s refashioning of Negro dramatic arts opened a new front in his continuing war with Black civil rights and service organizations, which he felt did not fully appreciate drama’s cultural service. Locke hoped to pivot among these many cultural players, pit them against one another when necessary, stimulate creative energies of a Negro drama situated in the 1920s moment, and force Americans to speak to one another. If he could establish his own authority over such a drama, then he might, through criticism, bring White and Black playwrights toward a truly exciting conversation about race in America.

Locke’s new approach in the drama and other arts paid dividends in expanded speaking opportunities. On May 12, he did one of the usual engagements, speaking to a Black, educated, lay audience in Washington. Anna J. Cooper’s cheeky comment exposed a bit of Locke’s self-inflation. “This is to remind you that we expect you Sunday May 16 … to tell us just what constitutes a race drama + how we may know it when we find it.”16 Paying opportunities came from White groups, such as the women’s university club of Grand Rapids that invited Locke to speak that fall. “The club is particularly interested in the artistic side of the negro movement, and feels sure that you could give a very interesting talk on the subject.”17 Part of Locke’s growing demand as a speaker in 1926 came from his ability to spice his presentations with witty, pithy statements. Lydia Gibson Miner teased Locke about one of his statements made at a visit to her school, namely: “‘Statesmanship as distinguished from its counterfeits is the art of making progress without revolution.’ A.L. Therefore:—Washington, Jefferson, John Adams, Samuel Adams, Cromwell, Massini, Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Robespierre, Dante, Lenin, Stalin, Bukarin, Napoleon, and others—a few hundred—were counterfeit statesmen. Q.E.D.”18

Locke’s “statesmanship” used art to triangulate the positions of White supremacy and Black protest and allowed liberal Whites and conservative Blacks to re-engage in the discussion of race without having to take sides, for example, on the lynching bill before Congress. Part of the appeal of The New Negro was that it could be accepted by conservatives who read its call for self-determination as another form of self-help. “You will be interested to know,” George Foster Peabody wrote to Locke, “that in a private letter from my very dear Friend, Honorable Newton D. Baker, he writes me as follows: ‘Locke’s The New Negro’ is a genuinely significant and helpful book. If it is widely read among the Negros it ought to do much to stimulate the best thought of the race toward the achievement of a culture of their own and so divert much of their passion which is now worse than wasted in demands for recognition, as a matter of right, which, in the nature of the case, can only come when they are won by service—in this case when time has had a chance.”19

Here was the risk of Locke’s new approach: it gave fuel to conservative Whites, who saw art as a diversion of rightful protest into “achievement” and “service.” Du Bois would make just this charge months later in “Criteria of Negro Art,” his 1926 critique of Locke’s position on Negro art, when he wrote: “there are others who feel a certain relief and are saying, ‘After all it is rather satisfactory after all this talk about rights and fighting to sit and dream of something which leaves a nice taste in the mouth.’ ”20 Locke’s philosophy of aesthetics could be a mask that allowed White patrons to feel all he was advancing was a way for Whites to feel more comfortable that instead of rebelling, Blacks were satisfied to write poetry and worship Western civilization.

But these patrons were also at times shocked at what reading and studying led Blacks to understand—their agency in constructing civilization. On one occasion, Peabody was horrified to learn second-hand from one of Locke’s students that the philosopher had advocated in one of his classes that the Nile was the birthplace of the Divine Being (perhaps a reflection of Locke’s Coptic view that the ark had been removed from Jerusalem to Abyssinia). Peabody quickly corrected Locke that it was the Judea-Christian heritage located in Jerusalem that was the source of all faith in the one and only God! Such slips into what Peabody must have thought was paganism were dangerous for Locke because he was relying on Peabody in his continuing campaign to get his job back at Howard. Peabody had just glimpsed what was true—that Locke’s attempt to restore the “proper” place of Africa within the history of civilization meant a radical displacement of the Judea-Christian heritage.21

Locke hid the revolution in global thinking implicit in a Black renaissance in order—and this is what Du Bois resented increasingly—to curry favor and get money from White patrons. But being unemployed, Locke was more vulnerable, more exposed to the market forces of unemployment in 1926, and more anxious that his writings serve a double purpose—to free the Negro and also to advance his own individual survival given that, as a Black homosexual, he was considered too toxic to be hired inside of Negro progressive institutions such as the NAACP and the National Urban League. Being an outsider to the Negro establishment drove Locke toward both a radical critique and a romance with the pillars of Whiteness. Without a job, Locke had to dissemble, bob and weave, and hope that he could advance a Black aesthetic without dashing his chance to get his Howard University position back because some trustee viewed him as a dangerous radical. Locke himself was looking for a renaissance in 1926.

Late in June that year, Locke left for Europe, having earned enough money from publishing and speaking to spend the summer abroad. He needed time in Europe to escape the quagmire of emotions that Black Washington had become for him. He wondered whether he should move permanently from Washington to New York, for in Harlem was developing a community of Black gay men who regularly saw one another in bars, cabarets, and nightclubs without the sense that they would be ostracized from the Literary Society. That sense of the private and the public also divided Locke from Du Bois, who could move easily between his professional life and spending evenings with a mistress, without fear of reproof if he was so discovered. For Locke, such freedom existed only abroad, in Paris or Berlin.

Locke also pursued other ambitions abroad. Through Helen Irvin Locke he learned that Dr. Mordecai Johnson, a Baptist minister, who was rumored to be on the short list of possible candidates for president of Howard University, was in Europe that summer. Irvin had known Johnson at the University of Chicago, thought well of him, and encouraged Locke to seek him out. Locke wanted to meet up with him on neutral ground to discuss his possible reinstatement. He managed to speak with him at length and was impressed by his intelligence, drive, and steely determination. Johnson’s selection encouraged Locke that Howard was finally going to get the New Negro leadership it deserved.

Just as Locke left America, Du Bois was thundering to the NAACP convention in Chicago that “all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists … I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda.”22 Linked to Locke’s growing frustration with Du Bois’s position was his sense that Du Bois knew such narrowing of the range of Negro art appreciation was a lie. Du Bois, no less than Locke, loved the sonatas of Beethoven completely apart from any consideration of their representation of German humanity. They both loved the poetry of Goethe, Shelley, and Keats, without cataloging how the writings of each elevated their respective peoples in world renown. Locke knew that in Europe Du Bois walked under the same nocturnal foliage in the Bois de Boulogne, enjoyed cafes in the same neighborhoods, and attended similar concerts. Indeed, Locke might have felt a bit of pity for the great Du Bois who seemed to sacrifice appreciation for the sublime in the fight for the Negro’s rights. Even in his Chicago declaration of all art is propaganda, Du Bois admitted that Beauty was something profoundly human that Negroes as well as all other humans had a right to.

Such is Beauty. Its variety is infinite, its possibility is endless. In normal life all may have it and have it yet again. The world is full of it; and yet today the mass of human beings are choked away from it, and their lives distorted and made ugly. This is not only wrong, it is silly. Who shall right this well-nigh universal failing? Who shall let this world be beautiful? Who shall restore to men the glory of sunsets and the peace of quiet sleep?23

Locke’s New Negro was a legitimate answer to these questions, as Locke knew that Du Bois loved the life of the cosmopolitan and its escape into art that was not political but somehow couldn’t admit it from the helm of the Crisis. Was Du Bois just a bit jealous that the younger Harvard man had found an aesthetic philosophy more popular with the younger generation of Black writers than his? Locke had had the good sense not to respond to Du Bois’s “Symposium” that February 1926, but when he returned to the United States he knew he would have to find a way to respond to what would become Du Bois’s “Criteria of Negro Art” to keep his position as the defender of Negro youth. For he and Du Bois knew that the Negro artist was the best suited to answer these questions, to “right these wrongs.” But Locke had few resources—he didn’t even control a journal as Du Bois did—“to restore men the glory of sunsets and the peace of quiet sleep.” Going abroad was a welcome escape from thinking about how tortured the American situation of race and beauty was for him.

When Locke’s thought did turn to race and art that summer, it went back to Hughes and their walks together through Paris in 1924. Having not been abroad since that rendezvous, Locke may have found himself yearning to reconnect with his elusive friend. Possibly this interlude back in Paris catalyzed in Locke a desire to move closer to an active, mentoring relationship with Hughes, despite the earlier frustrations. In some respects, Hughes was all that was left of the original quartet of promising Black poets: Jean Toomer had left the race; McKay was about to be his enemy; and Cullen was too absorbed in his own flattering press to devote himself to the serious work of improving as a poet. Hughes, along with Hurston, might be the only ones willing to undertake what Locke preached—immersion in the Negro folk spirit to create great art. Perhaps there was still hope that a renaissance grounded in Blackness could emerge in an America generally alien to the pursuit of Beauty he enjoyed in quiet evenings abroad.

That all changed when Locke returned home in mid-September 1926. Controversy had broken out, in all places, in the Nation. George Schuyler, the puckish, iconoclastic contributing editor of the Messenger, had published an article, “The Negro Art-Hokum,” that discounted not only the Black literary movement but also the notion that there was anything culturally distinctive about the Negro to express. A week later came a bombshell from Langston Hughes. “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” was the young Negro artists’ declaration of independence. “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If White people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. … If colored people are pleased we are glad. If not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either.” Hughes had also attacked Cullen, whose review of The Weary Blues had chided his rival for confining himself only to poems on Negro subjects. In a barely veiled reference, Hughes suggested that because Cullen wanted to be considered a poet, not a Negro poet, that Cullen wanted to be White. Such reductionism, so popular during the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, suggested that only the poet who embraced race, regional, or national identity could become a great poet. Hughes’s racial romanticism was compelling in 1926, because he linked it to an attack on the Black bourgeoisie, whom he argued so lived their lives for White approval that they distanced themselves from the “common people.” Hughes included a critique of one of Locke’s hang-ups, his distaste for jazz and the blues. “Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing Blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near-intellectuals until they listen and understand … [and] … catch a glimmer of their own beauty.” He claimed his audience and sympathetic critics should embrace these new forms as repositories of authentic Blackness.24

Locke had ignored “The Negro and the Racial Mountain,” which was published just before his departure to Europe. But he could not ignore Hughes’s challenge to transcend high aestheticism when he returned in September. In August, Carl Van Vechten, Hughes’s patron, had published Nigger Heaven, which had become a commercial success, but also confirmed Du Bois’s prediction that a focus on Beauty would lead the Negro Renaissance into decadence. Lurid, exotic, and erotic, Nigger Heaven not only had an insulting title but was also seen by many Black intellectuals as a slap in the face from a White author reputedly the Negro’s friend. Although James Weldon Johnson and Hughes defended Van Vechten, the book and the controversy it spawned made its author a pariah in some circles. Locke refrained from publicly commenting on Nigger Heaven and used the fall publication of his review of The Weary Blues in the Black literary magazine Palms to defend Hughes’s first book of poems from criticism by Black philistines. “There are lyrics in this volume which are such contributions to pure poetry that it makes little difference what substance of life and experience they were made of,” Locke began, acknowledging the controversy over whether the work in The Weary Blues was really poetry. “Nor would I style Langston Hughes a race poet because he writes in many instances of Negro life”—which was also Locke’s answer to Cullen’s criticism. This was Negro poetry “because all his poetry seems saturated with the rhythms and moods of Negro folk life.”25

That argument allowed Locke to confront the man whom he increasingly felt was a rival and bad influence on Hughes. “Taking these poems too much merely as the expressions of a personality, Carl Van Vechten in his debonair introduction wonders at what he calls ‘their deceptive air of spontaneous improvisation.’ ”26 In fact, there was an element of “deception” in that the poems were close transcriptions of blues Hughes had collected. Zora Neale Hurston put it bluntly in a letter to Cullen. “By the way, Hughes ought to stop publishing all those secular folk-songs as his poetry. Now when he got off the ‘Weary Blues’ (most of it a song I and most southerners have known all our lives) I said nothing for I knew I’d never be forgiven by certain people for crying down what the ‘white folks had exalted’, but when he gets off another ‘Me and mah honey got two mo- days tu do de buck’ I don’t see how I can refrain from speaking. I am at least going to speak to Van Vechten.”27 Hughes mined a tradition, really two traditions, since his poems embodied “the rhythm of the secular ballad, but the imagery and diction of the spiritual.” Locke’s language of the “secular ballad” suggests he had still not embraced the jazz and blues traditions. But his sense of Hughes’s ability to translate the Negro “spirit” into free verse allowed Locke to designate Hughes “spokesman” for the Negro masses. But haunting his approval was Locke’s sense that Van Vechten, an aged homosexual spoiler of young Black men, victimized Hughes’s work. Locke defended himself psychologically against any self-consciousness that he did the same thing.

When Locke left for Europe, Du Bois had delivered his “Criteria of Negro Art” speech at the NAACP convention in Chicago, which was published in October, a thinly veiled attack on Locke and the New Negro writers embodied in his declaration that “all art is propaganda, either for or against the race.” Shortly after he returned, Locke was confronted with an explosive answer to “Criteria” that November in Fire!!, a collection of writing “devoted to the younger Negro artists,” edited by St. Louis–born Wallace Thurman, a Black editor of the Messenger, who collaborated with Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Lewis Alexander, Aaron Douglas, and several others. When Fire!! appeared, it brought a bold Egyptian-inspired silhouette cover by Aaron Douglas, poetry by Hughes, a play by Zora Neale Hurston, and a homoerotic short story, plus contorted line drawings by Richard Bruce. Fire!! was an attack on the moralizing sensibilities of the Black bourgeoisie, an “art for art’s sake” publication that used folk, working-class, and sexual innuendo to advance the credo of the romantic artist. Locke gave qualified praise to the effort in his review of the first issue in the Survey Mid-Monthly as “a gay and self-confident maneuver of artistic secession.” Locke’s reference to “secession” invoked the series of European rebellions by visual artists, some of which his friend Winold Reiss had participated in during the early twentieth century to hold exhibitions of work rejected by the art establishment. In this case, the Black “secession” was a rebellion against the sensibilities of the Black bourgeoisie. Ironically, in a magazine that Thurman wanted to be free of “Nordic” influence, it was a White man, Carl Van Vechten, who provided last-minute funding so that the magazine could be printed.

But Locke was somewhat critical of the quality of the work in the issue. “The churning eddies of the young Negro mind in the revolt from conservatism and convention have not permitted this to come clearly and smoothly to the surface,” producing as yet “more of a drive than an arrival, more of an experiment than a discovery.” Locke could also not pass without noting the “strong sex radicalism of many of the contributions” that he predicted would “shock many well-wishers and elate some of our adversaries.” Here was Locke’s limitation as a closeted gay critic: he did not support a literature that made sexual desire the explicit pivot of Black creativity. What Locke believed limited this work was generational rebellion for rebellion’s sense. Locke hoped that in “subsequent issues, the younger Negro literary movement will establish its own base and with time gain a really distinctive and representative alignment.”28 But with poor sales, widespread Black condemnation, and a mysterious fire that consumed all the remaining copies of the first issue, no further issues of Fire!! appeared.

Nevertheless, by balancing his approval and critique, Locke found a way to give the magazine qualified praise and avoid alienating himself from the radical wing of the New Negroes. In doing so, he distanced himself further from Du Bois, who could not accept its foregrounding sexuality and amorality. But Locke began to have doubts about these young Black artists, who seemed committed to nothing beyond their own freedom. Privately, he worried that Thurman and his friends lacked a serious aesthetic philosophy and were motivated largely by a desire to give little more than a sexual identity to the Negro art movement, which he believed was reductionist.

More fireworks were in store for Locke. Hughes’s second book of poems, Fine Clothes for the Jew, appeared in November and raised a storm of criticism from the Black press. The Pittsburgh Courier roasted Hughes for publishing a “vulgar” volume of poetry; the Philadelphia Tribune was repulsed by the “lecherous, lust-reeking characters that Hughes finds time to poeticize about.” Given an opportunity to rebut the charges in the Courier, Hughes wrote “Those Bad New Negroes: A Critique on Critics,” which was published in April 1927. “I have a right to portray any side of Negro life I wish to,” Hughes wrote. By attacking the Black patronage class, rather than cultivating it, the “Young Turks” of the Negro Renaissance doomed the movement to either dependency on White patrons or an early death. Many of Hughes’s critics blamed Carl Van Vechten for influencing him toward decadence. Locke also worried that Van Vechten was at least partly to blame for the superficiality of some of the artist’s poems. But without the publishing contacts and associations of Van Vechten and Walter White, or the publishing outlet of Du Bois, Locke lacked the leverage to tilt Hughes or other artists toward the fundamental values he extolled.

While Locke began to have reservations about much of the writing coming out of the Renaissance in 1927, he decided that his public role was to defend the youthful writers against what he thought was hysterical condemnation by their critics. In “Our Little Renaissance,” his first rebuttal to such critics, in his contribution to Charles S. Johnson’s anthology, Ebony and Topaz: A Collectanea, Locke characterized the White critics of the movement as condescending. H. L. Mencken did not think the movement was Black enough, a “candle in the sunlight. It has kindled no great art.” Heywood Broun, whom Locke had tried to get to contribute to The New Negro, allowed that the movement was “fairly successful, considering … the American atmosphere,” and was “still full of promise-so it seems.” Locke could not help ”wonder what Mr. Pater would say. He might be even more skeptical … but one mistake he would never make—that of confusing the spirit with the vehicle, of confounding the artistic quality which Negro life is contributing with the Negro artist. Negro artists are just the by-product of the Negro Renaissance; its main accomplishment will be to infuse a new element into the stream of American culture.”29

Locke’s aesthetic idealism seems at first a sleight of hand. Given that Locke was beginning to feel that the artists so far had underperformed, he shifted the discussion to the idea of the Negro Renaissance, rather than its accomplishments. In doing so, he made a profound interpretation of the Italian Renaissance, suggesting that Michelangelo, da Vinci, and Botticelli were not the most important contributions of the “real” Renaissance, but its awakening of humanity to its own agency and creativity. Locke also took a shot at Du Bois. “We must divorce it in our minds from propaganda and politics. Otherwise, why call it a renaissance?” The revival of Humanism and Beauty within America through the art of the Negro experience was this renaissance’s most important contribution to world history. The idea of a New Negro Renaissance was above all a call to recognize the redemptive force of African American literature and culture in Black lives.

Locke also sought some redemption. As early as his fall 1926 return to the United States, Locke had lobbied Arthur Mitchell to arrange a private meeting with Emmett Scott, who stated he was amenable to Locke’s reinstatement. But Scott also shared with Mitchell “some particulars” of Locke’s case that Mitchell thought should be shared with Locke only in person. What were those? Were they sexual accusations? Or rumors? Did Scott want Mitchell to obtain some assurances from Locke that his behavior would be above reproach before he was readmitted to Howard? We do not know. Even after those conferences, no action occurred. Locke’s friend Metz T. P. Lochard, also fired, gave up hope and took a position with the Chicago Defender. Other options seem to close for Locke just as they opened up for the others. Locke had attempted to get a license to teach at a New York high school, but that hit a snag when two of the three doctors who examined Locke deemed him unfit for the rigors of teaching because of his heart. If that was not bad enough, Lewis Marks, the examiner, notified Locke that even if those difficulties could be cleared up, there was also the matter of a negative report given to the New York schools by Durkee, who referred to Locke as having been dismissed because he was an incompetent teacher. That retaliation required Locke to solicit from his former dean, Kelly Miller, a letter attesting that Locke had been an excellent teacher and that Durkee was a vindictive administrator with little or no knowledge of the abilities of the teachers at Howard University. As this struggle to win what was simply a demotion showed, the forces allied against Locke in early 1927 were formidable. As the winter deepened, he seemed to have no real prospect of getting his job back at Howard.

But in May 1927, something magical happened. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote to Jesse Moorland and stated: “I am interested in having Alain Locke reinstated at HU.” He wrote to Moorland because “I have been told by disinterested parties that the chief objection to Locke is from you.” Du Bois went on to make clear that he was not doing this out of some personal interest. “While I have known Mr. Locke for sometime, he is not a particularly close friend. I have not always agreed with him, and he knows nothing of this letter.” Rather, Du Bois wrote because of two larger principles at issue in Locke’s case:

First there is the privilege of free speech and independent thinking in all Negro colleges. We have got to establish that, and the time must go when only men who say the proper things and walk the beaten track are allowed to teach our youth. Of course, there must be limits to this freedom, but the limits must be wide. In the second place, we must have cultured and well-trained men in our institutions. We have lamentably few. Locke is by long odds the best-trained man among the younger American Negroes. His place in the world is as a teacher of youth. And he ought to be at the largest Negro college, Howard. Nothing will discourage young men more from taking training, which is not nearly commercial and money making, than the fact that a man like Locke is not permitted to hold a position at Howard.30

Apparently, Du Bois’s extraordinary act of generosity did the trick. The board of trustees reappointed Locke as professor of philosopher at Howard that summer. Ironically, this appointment came after Locke had been invited to spend the 1927–1928 academic year at Fisk University. In order not to penalize Fisk for its cordiality when he was desperate for a teaching job, Locke honored the Fisk appointment and began teaching at Howard University in the fall of 1928.

It is not certain Locke knew of Du Bois’s intervention. Indeed, there is no proof that anyone informed Locke, least of all Du Bois. But that Du Bois knew that Moorland was the man blocking Locke—and others as well who had informed Du Bois of this fact—created a crisis for Moorland that could only worsen and become public had Moorland not conceded. The Negro newspapers, still on Locke’s side in the controversy, would have made scandal out of the news that a Negro educator blocked the reappointment of “the best-trained man among the younger American Negroes.” Although Locke considered Du Bois his nemesis, the Crisis editor was actually his savior.

Why did Du Bois do it? As David Levering Lewis puts it, Du Bois and Locke were not friends. Du Bois never forgave Locke for trying, with Charles Johnson, in 1923, to get Beton to write an article critical of the Pan African Congress in Opportunity nor for trying to marginalize Jessie Fauset by excluding her from The New Negro: An Interpretation. Du Bois also appeared to disapprove of Locke because of his homosexuality. And yet, Du Bois wrote a letter that rescued Locke’s professional career, shortly after Du Bois dismissed his business officer, Augustus Dill, ostensibly for public solicitation of another man. Was his letter to Moorland an act of unconscious atonement? Of course, in Du Bois’s mind, the two cases were different for many reasons, not least of which that Locke was never arrested for any public display of his sexual orientation. Locke’s “paralyzingly discreet” approach to his sexuality meant he was never an embarrassment “to the race,” a critical issue for a race war general like Du Bois. But the possibility remains that Du Bois’s act of simple justice was buttressed by a more complex internal balancing act, his emerging self-awareness of the cruelty of his own act of dismissing Dill and his compensation for that act by saving another of similar orientation.31

That intercession did not change their professional or personal relationship. Du Bois and Locke remained adversaries. Their conflict over art heated up again in 1928, just as Locke returned to Howard. That October, Du Bois turned over the attack to one of his younger minions—Allison Davis—who published “Our Negro Intellectuals” in the August 1928 issue of the Crisis. Davis attacked the entire group of New Negro writers for spreading filth as literature under the ideology of “sincerity” and artistic freedom. For Davis, “the plea of sincerity, of war against hypocrisy and sham, therefore, is no defence [sic] for the exhibitionism of Mr. George S. Schuyler and Mr. Eugene Gordon, nor for the sensationalism of such works as Dr. Rudolph Fisher’s HIGH YALLER or Langston Hughes’s FINE CLOTHES TO THE JEW.” Davis charged that all were imitators and protégés of Carl Van Vechten and H. L. Mencken, that Black writers had bought into the “romantic delusion of ‘racial literatures,’ ” and charged them with exploiting the desire for a distinctive Negro by “use of the Harlem cabaret and night life, and … a return to the African jungles” in their poems and novels. Davis even hit at James Weldon Johnson for having felt the need to “yield to this jazz primitivism in choosing the title GOD’S TROMBONES for a work purporting to represent the Negro’s religious fervor” and even “Mr. Miguel Covarrubias and Mr. Winold Reiss [who] did more than Mr. Aaron Douglas and Mr. Richard Bruce to represent the Negro as essentially bestialized by jazz and the cabaret.” To make sure he did not leave out an attack on Locke’s role, Davis attacked the “criticism” that had emerged with this movement as lacking “a vital grasp upon standards” to resist the temptation to praise what was only a “gushing forth of novelties.”32 As Van Vechten wrote to Hughes on August 2, 1928, “Allison Davis’s article was both asinine and sophomoric. I’m glad you answered it, but what can you think of Du Bois printing such rubbish.”33 But that he did it reflected how angry Du Bois was with the “renaissance” he forecast in 1920.

Once Locke had gotten his job back, he felt more comfortable confronting the issue of propaganda out in the open. In an article, “Beauty Instead of Ashes,” published in the Nation in April 1928, he argued that the art movement had been “a fresh boring through the rock and sand of racial misunderstanding and controversy” that had delivered to America a “living, well-spring of beauty.”34 Locke turned the criticism of current writers and their products into a larger question: could this opening be the beginning of something permanent, or would the attackers from the wings of racial controversy succeed in killing the “first products” of the renaissance and forcing Black self-expression to begin anew—all over again. Here, Locke built on his assertion in “The Drama of Negro Life” that the Negro Renaissance had advanced because of a “division of labor” between White and Black writers, and this time argued Blacks had excelled at poetry, while Whites had pioneered novel and playwriting. He sided with Hughes on Nigger Heaven, stating that while it was “studied,” Van Vechten’s was a “brilliant novel of manners”; similarly, he rebutted the criticism of White playwrights like Du Bose Heyward as a mistaken view that the modernist portrayal of the “folk-life” was racist when, in fact, in many cases, it was the “folk” to whom the White artist gained access. He ignored the power issues in such access, that the poor had few resources with which to defend or reshape their representation. It was hypocrisy for the Black elite to complain of their lack of portrayal by White writers and then deny those same writers access to its material.

Locke’s only criticism came when he “hoped” that “the later art of the Negro will be true to original qualities of the folk temperament.” The full promise of Negro literature remained in this arena, the site of an “inner vision” of what it means to be Negro. “That inner vision cannot be doubted or denied for a group temperament that, instead of souring under oppression and becoming materialistic and sordid under poverty, has almost invariably been able to give American honey for gall and create beauty out of the ashes.”35

While Locke sympathized with Du Bois’s demand for more balanced treatment, propaganda literature had failed. The Negro creative spirit had moved on, even if it incurred new demerits because of the sophomoric antics of the “young Negro artist.” One could not create Beauty out of retaliatory anger or hyper-moralism. The deeper philosophical point was that propaganda made Black expression dependent on the White man. Locke made precisely that point in “Art or Propaganda?” his last and most forthright answer to Du Bois, when it was published in Harlem, the second magazine edited by Wallace Thurman. Setting aside his misgivings about Thurman, Locke rose to the occasion one last time to defend his movement against Du Boisian prescriptions. “My chief objection to propaganda,” he wrote, “apart from its besetting sin of monotony and disproportion, is that it perpetuates the position of the group inferiority even in crying out against it.”36 Locke wanted Black people to stop thinking of themselves as victims. He did not think as a victim, even though he was queer, Black, and unemployed much of 1926 and 1927. He might be marginalized by discourses of Whiteness and heterosexism, but his message was strong and unmistakable: move beyond Du Bois, and start thinking and acting like we own American literature. Negro art should subjectivize the Negro, make them powerful human beings, not repudiations of White racist stereotypes. Art should restore the “inner vision” of the Negro even in the midst of a debilitating American civilization.

African art offered the possibility of seeing Black people from the inside and not through the White lens of the Enlightenment. Building a foundation of art on the African traditions offered the opportunity to reveal the “true” identity or Idea of the Negro. That this was not yet evident was not evidence that it did not or could not exist. African art proved that Black people had created tens of thousands of objects of great beauty under different circumstances and (here came something of the aesthete) lived lives in which practical living, spirituality, and devotion to Beauty were intertwined inseparably. It could be expressed again if African Americans saw themselves as a modern people with ancient creative traditions despite American circumstances.

Locke’s vision remains a curious blend of pragmatism (“psalms will be more effective than sermons”) in converting the heart of the oppressor to empathize with the oppressed, religious consciousness (a blend of Christianity and his Baha’i faith), mild Afrocentrism (a return to an African past as a non-Western basis of a Black modernism), and philosophical idealism. He aimed to modernize Black thought by sidestepping the hurt of the past.

That night in the mid- or late 1920s, when Locke and Du Bois finished their dinner in Washington, one wonders what they said as they prepared to part. Perhaps the traditionally tight-lipped Du Bois had little to say. Locke, proud and resentful of any demand for deference, probably could not bring himself to thank Du Bois if Locke knew of the older man’s remarkable intervention in saving his academic career. Perhaps both could agree they hoped an artist would emerge who advanced the race as well as art. The controversy over art and propaganda had divided them, but not destroyed their cordiality. Their Black Victorian backgrounds, sense of manners, taste, and decorum, had served their relationship well. Unlike some of the younger writers coming after them, they believed that Black intellectuals could not afford to self-destruct, even when they strongly disagreed.

“Now, Dr. Locke,” Du Bois might have ventured to ask as they got up from their meal, “Who among the new young writers has the potential to write something beautiful?”

That question would have made Locke think a long time.

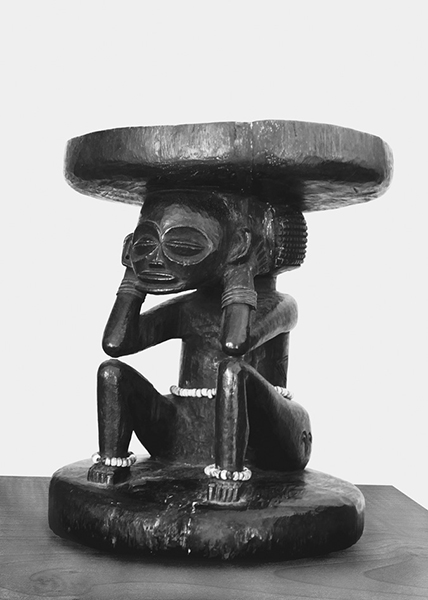

Chokwe Stool. Blondiau-Theatre Arts Collection. Private Collection.