30

Langston’s Indian Summer

As Locke traveled to Europe during the summer of 1927, Mason’s attention shifted to Langston Hughes, himself on the way south. After Hughes’s second book of poems, Fine Clothes for the Jew, was almost universally attacked by the popular Black press (one newspaper writer declaring that he was “sickened by the ‘lecherous, lust-reeking characters that Hughes finds time to poeticize about’ ”), Hughes retaliated with his article titled, “Those Bad New Negroes: A Critique on Critics,” published in the April 14 issue of the Pittsburgh Courier. There he declared, “I have a right to portray any side of Negro life I wish to.”1 Shortly afterward a more serious condemnation of the entire Negro Renaissance appeared from the pen of Benjamin Brawley, an English Department colleague at Howard University. Unable to find a single quotable line in Color, Brawley argued that Cullen was overrated and singled out Hughes as the saddest case of the younger Negroes. He had talent, Brawley concluded, but “squandered it” under the influence of Carl Van Vechten. Although Van Vechten replied to Brawley’s article privately, and Hughes wrote publicly disclaiming the influence of Van Vechten on his poetry, it was clear to Locke that the movement was losing support among educated Blacks in the North. And the stigma of association with Van Vechten was not helping Hughes. Such attacks gave ammunition to someone like Mason who believed that the condemnations were reactions to Van Vechten’s influence, which she sought to replace with her own.

Touring the Deep South, beginning in New Orleans, which celebrated and feted him as a still-revered poet of the race, Hughes had the good fortune to run into Zora Neale Hurston, who was collecting research for Franz Boas at Columbia University, where she was a student. Hurston was already well known as an interpreter of the southern rural Negro, most famously for her short story “Spunk.” Locke also had suggested Hurston as a potential recipient of Mason’s funding, as he had liked Hurston since her student days at Howard University, where she was one of the outstanding students who participated in both the Howard Players and the Stylus literary magazine. Hughes also told Hurston about the white-haired, bespectacled, old benefactor who had so impressed him with her money and her conversation, and recommended that she contact Mason when she returned to New York that fall.

Hughes must have given Mason an itinerary of his trip, because periodically throughout his tour he received letters, money, and telepathic support from Mason, who was then spending her summer in Connecticut. Mason told him she was monitoring his progress spiritually and becoming more involved emotionally in his quest to collect and represent the culture of the southern Negro in his next work. With only one private meeting, Mason already felt comfortable telling him that “he must say nothing of his trip to his friends when he reached Manhattan, so that ‘later when you are ready to use it the flame of it can burn away the debris that is rampant here.’ ”2

In that advice coalesced two aspects of Mason’s anti-modernism. First, she possessed a conspiratorial, paranoiac opposition to “Western Civilization” and her desire to reclaim a spirituality she believed still resided in true heirs of “Primitive Man.” Part of her insistence that people working with her isolate themselves from society came from her belief, shared by other reactionary modernists, that there was something profoundly destabilizing and maddening about life in the modern city. The true artist, in this narrative, was the heroic individual who transcended destabilization through a spiritual grasp of what was truly eternal.3 Second, Mason, like some other modernists, ironically, believed a return to the past would recuperate a spirituality that was true and liberating only if it was based on discipline and control.4 That’s where her role came in: she was put on earth, it seemed, to inject this discipline in the heirs of “Primitive Man” to make sure they honored this heritage and were not themselves distracted by the false rewards offered by association with “Western Man.” This discipline connected with her cruelty: like a mother chastising errant children, Mason’s purpose was to force modernizing Blacks back into connection with a world of spiritualism Black migrants had left behind, according to Locke, when they came north to “modern America.” Here was the deepest contradiction of Locke’s courtship of Mason. She rejected the city, the world he had written about in the Harlem number as the liberation of the Negro. She was enlisting Hughes in a counter-revolution against the work, the voices, and the hedonistic lifestyle that his poetry had chronicled as the new Black way of living in the city in early twentieth-century America.

That Hughes did not immediately object to her presumptuousness in telling him with whom to discuss his findings suggests that he too possessed a psychological need that Mason perceived and capitalized on. Hughes was deeply alienated from his father, and in search of a lost mother to nurture his desire for a creative career rather than the business career his father had thought he was paying for when he sent his son to New York for an education. Hughes needed someone powerful to solve his financial needs—Mason eventually paid for his brother to attend school with payments made through Locke—but also his psychological need for support and reinforcement to make a go of it as a self-supporting Black writer. Hughes harbored many secrets—about sexual partners and proclivities, his whereabouts and travel plans, his inspiration for his poetry, and so forth—but also a latent conspiratorial attitude that he, like other rebellious Black artists, was engaged in a struggle to overcome the worst aspects of a Western civilization, some of which were disseminated by other Blacks. Mason exploited that attitude among Black creatives, as did Jean Toomer’s mentor George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, who demanded secrecy of his charges to prevent “premature” airing of their ideas that might thwart the spiritual revolution they hoped to initiate.5 Plus, secrecy would ensure that it would not be widely known Hughes was taking money from an old White woman to make a go of it as an independent Black writer.

When Hughes returned to New York that August, he hurried for a meeting alone with Mason. There he reported on his trip, including his travels with Hurston, and his plans for the future. Again, presumptuously, she told him that he ought to use the material to write a novel, a suggestion he was not enthused about. But Hughes did not reject her suggestion, just as he did not tell Van Vechten the year before that he had no interest in writing an autobiography. There was something in Hughes that allowed White patrons to press upon him suggestions they expected to be followed and that he refrained from squashing. Perhaps he expected them to forget or relinquish. He did not yet know that Mrs. Mason never forgot a demand. She also advised him to leave New York immediately. But he stayed in town, hanging out with friends in what was and still remained his natural atmosphere, the urban Black landscape he had helped to foster and celebrate in his poetry.6

Locke exhibited considerable resistance to her total control over his activities, which was one of the reasons Mason became increasingly involved with Hughes. A gap occurs in Locke’s correspondence with her from June 21 to September 13, 1927, when he writes her on his birthday. Throughout July and August, Locke reputedly sequestered himself in France writing an English translation of Batouala. Yet the translation was never published. And later letters to the Nadal sisters employed by Rene Maran to do a translation suggest that if his translation survived it was so poor as to be unusable as a basis for their translation. What he may have been doing is hiding out in the internationalisme noir, Jane Nadal’s telling phrase for the transnational community of Afro-Diaspora intellectuals in Paris, that included Jane Nadal, her sister Paulette, and Rene Maran, among others. Months later Jane Nadal would write Locke asking permission to translate The New Negro into French, as a way to open up the minds of the French to the Black consciousness movement outside of France. Locke agreed, even wanted to join in in the effort of translation, because by working collaboratively with the Nadal sisters, he might have produced a “trans-interpretation” of the New Negro concept into new intellectual as well as geographical territory. Locke may have kept Mason in the dark to exclude her probing eyes from a different kind of family abroad, where he could experience the kind of peer production of new knowledge he had hoped for in the patronage scheme but not experienced so far.7

When Locke wrote Mason in September, he was ensconced in Geneva and facing the work that he was supposed to do, that of investigating the League of Nations’ handling of the African Mandates System. “Dear Godmother: Your wireless birthday greeting reached me at 11 a.m. Already the air was full of ozone—an unusually beautiful day. Your words brought streams of strength and inspiration—as I can prove to you in a few minutes.”8 He wrote her passionately, linking her influence to that of his mother, and crediting her guidance for whatever he accomplished. But at the same time, he subverted her control. He did not send her a copy of his address before the League, as he had promised to do when he left. He did not give her up-to-date reports on his activities, which could have allowed her to intercede and direct them, but instead gave her after-the-fact summaries. And he pursued a schedule of activities at odds with her advice to focus on conducting research for the Mandates report and deemphasize other, scattering activities. His experiences negotiating the rituals of segregation as an African American at the League meetings was the focus of his thinking.

It has become quite clear that the investigation of the League matters is the secondary matter. It has been the personal contacts that have counted—and the effect on the American colony here has been remarkable. Their first effort was an obvious effort to make an exonerating gesture here before European eyes. Gradually, I think the thing has taken a deeper hold on them—as today for example I am sure it has been due greatly to the fact that I have been reserved and have cut a few previous invitations. When Mr. McDonald kept me standing at the street corner while he finished a tea table conference (this was at an open sidewalk café) I eased out of his invitation to tea by asking him if he didn’t want to continue the conference—I could just as well see him some other more convenient hour. So—today I was asked to the lunch for Locheur (Briand’s right hand man) and put in a place evidently very carefully thought out—between Professor Holcombe of Harvard and Dean James of Northwestern. This afternoon still later Mrs. Grosvenor Clarkson had a tea for the Holcombes, myself and Ruth Pennybacher (of Galveston Texas) who you can see by the circular is an authority on “The Negro in Literature.” I afterwards learned it was a “by request” affair—It was amusing. I wonder if they really think I can’t see through it. It is good to learn how really sensitive they are before Europeans; and how easy it is to blackmail them into the reverse of their usual attitude.9

This was Oxford all over again, Locke performing Negro representation in a previously segregated global political space. What he did not see is that it was going to have a similar outcome. Instead, he reveled in employing poetry from Hughes and Cullen or from time to time “a perfectly frank statement about the situation in America (if a foreigner is present) to confound them completely.” Locke was easily distracted. “Geneva is a whirl—and it isn’t easy not to whirl with it. At times I have. But every once in a while I lay hold of your counsel and steady myself. And when I do—things just come to me. The scheme for African Studies at Howard—of which I have already told you, was one case in point. Another [was] Holcombes’ volunteering today to get a grant from the Harvard research fund for preparing a young Negro in international government. The man whom I mentioned—Kirkland Jones—happened to have been one of Holcomb’s former students—so I daresay that it will go through.”10 Of course, Mason had nothing to do with his African Studies suggestion, but Locke made every effort in his correspondence to Mason to attribute to her “counsel” any advance that he made to reinforce her feeling that she was essential to his success.

In Geneva, however, Locke was operating on his own. He met and impressed many Whites, especially the famous writer Romain Rolland, to whom Locke introduced the notion “that we too think to bring a unique cultural element into the world.” Rolland promised to “think about it more—I will welcome it, if I can. I am not strong—but I must live to see a universal humanity dawn.” Then, Locke rushed on to another event, another person to impress with his social skills or his connection to an African humanity only recently considered part of the universal community. Perhaps aware that the letter might disappoint Mason in that he was not doing what she counseled him to do in such situations, he closed on a flattering note. “It is due to your wisdom that I see a real vision ahead.” Aware of her concern to see some fruits of her investments of money and counsel before her death, he hoped that “it only come quickly forward so that you may have the joy of seeing it and I the joy and help of sharing it with you. And today, Godmother, it isn’t only I myself that thank you—it is mother, and father too,—who did all they could by way of parentage.”11 Clearly, Locke felt elated on his forty-second (though he represented to Mason as his forty-first) birthday. But Mason seemed more immediately impressed by the work being done by Hughes who, after all, was in the field actively collecting folklore with Hurston, rather than jetting around Geneva representing the race.

On September 20 Hurston met Mrs. Mason at her Fifth Avenue salon. Hurston was overwhelmed by a coincidence of her arrival at Mason’s apartment—that Cordelia Chapin was arranging calla lilies when she entered, an image from a childhood dream that Hurston had carried with her from the South. Her meeting with Mason, therefore, fit her prophetic dream of entering a big house with two women—one old and one young—who welcomed her and culminated her “pilgrimage.” Like Locke and Hughes, Hurston had a complicated relationship with a mother who superficially supported, but also limited, her abilities. Now, Hurston came face to face with a White woman who could be her all-powerful mother too and facilitate her dream to become an independent researcher and writer of fiction based on the life and culture of the rural Black poor. After the meeting, she confided to Hughes that she and Mason had gotten on very well and that she hoped Mason would take her up. Her own recent attempts to conduct the kind of folklore research she wanted to collect had left her depressed about future prospects without an infusion of cash and real concern. That was forthcoming.

But first Mason consolidated her position with Hughes. In October, she met with him again, alone, this time for seven hours, during which he found that he was never bored and that she was “entirely wonderful.” No, he had not made progress on the novel, but she was not concerned about that. What she was concerned over was that his situation was so scattered and his money so thin that it was impossible for him to devote himself to such a project. Although they discussed the folk opera that Hurston had told Mason about during her meeting, Mason was more committed to funding his research. She was ready to make him an offer he could not refuse. In order to help give flight to his creative spirit, she would pay him $150 a month for a year, and his only obligation would be to report his expenditures fastidiously. The actual details of the payments she would arrange later in consultation with Locke. Although Hughes took a few days to decide, the decision was already made for him by his previous behavior: strapped for funds, unable to work at creditable jobs while he was still a student at Lincoln University, where he was dependent on Amy Spingarn to pay for his tuition and living expenses, Hughes could not help taking this old woman up on an offer that seemed based on who he was, not what he would produce.

Yet that erroneous impression resulted from Mason hiding her real intentions. The maternalism in which she wrapped her offer disguised the real basis of the relationship she proposed to Hughes. Actually, he was being paid to work, in an arrangement that resembled a retainer, but she did not reveal this. And Hughes, as an artist and a man, was seeking escape from the series of service jobs in restaurants, on the one hand, and the crushing assembly line work of the industrial world, on the other. In a sense, part of what attracted him to this arrangement was what attracted him to being an artist in the 1920s: it was an escape from the world of banal work his father reverenced as the essence of a modern Black identity, a world of work embraced by the Black proletariat whose lives fueled his poetry. Rather than becoming one of them, Hughes wanted to be their bard, to speak for their condition without living it. What he and others of the Harlem Renaissance sought was a freedom from the modernizing yet dehumanizing conditions that had made the Great Migration possible. What he did not yet realize was that freedom from this kind of work came at the price, in his case, of acquiescence to a premodern form of patronage.

Zora Neale Hurston was perhaps even more willing to take whatever supportive patronage Mason offered. In the 1920s Hurston lacked the plethora of sympathetic White friends that Hughes enjoyed. Hurston knew that Mason was her one good chance. For different reasons, Mason liked Hurston immensely—in part because of her performative genius, her ability to tell jokes to mimic others at parties, and to utilize the full range of her intellect to deconstruct the pretensions of Negroes of talent, whom she derisively termed the niggerati. There was also a touch of the macabre in Hurston, a sense of almost self-destructive exuberance in the face of danger, that allowed her to travel the highways of the rural South alone. She also understood that the renaissance was mainly a male movement dominated by gay Black men. She could not appeal to these men and gain their support by mastering the feminine ways of the Black Victorians. She was not a schoolteacher or a librarian. She was older than all of the other “younger Negroes” and lacked their finesse. But what she had was a dedication to the vocation of the folklore collector and creative writer. If she could get this old woman to believe in her and fund her work, she would do whatever it took to keep her interested. Moreover, genuine affection surfaced between them.

Also of importance to Mason was that Hurston was a woman and an anthropologist, given her own early career as a researcher among Native Americans. But Mason also saw her as somehow beneath Locke and Hughes—one was a world-renowned intellectual, regardless of his annoying sycophancy and Edwardian fussiness, the other a well-published and universally acclaimed poet, who was well supported by Mason’s rivals in the Harlem Renaissance. Although she identified more with Hurston, Mason knew that Hurston was not yet a bona fide star; and, Mason knew she could cut a favorable deal with Hurston.

Thus, on December 8, 1927, Mason got Hurston’s signature on an unusual contract—to employ (here the exchange character of the patronage relationship is made explicit) Hurston to go south during 1928 and collect southern Negro folklore that would hereafter become the property of Mrs. Mason. In a manner similar to that of Blondiau, who had collected and made the art of the Congo his property, Mason colonized the intellectual property of the Black southerner herself. The contract could be extended, she assured Hurston, if all went well, subject to review of her performance by Mason in consultation with Locke. It is difficult to tell whether the exploitative nature of the arrangement eluded Hurston or that she accepted it as inevitable.

The benefits of the arrangement must have seemed to Hurston straightforward: she would be freed of the academic oversight and inadequate funding she had labored under for some time. And Hurston probably felt that she was skillful enough as a manipulator to manage the problem implicit in the arrangement, that she would have no right to utilize the material she collected in her own work. In this, Hurston’s reluctance to contest the terms of the contract had roots in her own complex relationship to the collection and utilization of folklore material in her own creative work. Part of her desire to sign the Mason contract was her desire to elude the kind of academic strictures on the use of folklore in anthropological scholarship. By accepting this contract, she thus gained freedom to pursue a potentially problematical overlap in her folklore collection and her creative writing, a problem of borrowing and using without attribution the cultural products of the subaltern. Because Hurston was Black, she had, as Locke would later put it, a “passport of color” that allowed her greater access to such material than Mrs. Mason would have had if she could have physically made the trip south. In 1928, the racial consciousness of most southern Blacks would not allow Mason the kind of access she had enjoyed earlier in the century among Indians. Employing Hurston to do this work was thus a shrewd move. Not only did Mason get the use of Hurston’s body as a collecting subjectivity but also she encouraged Hurston to collude with her in the appropriation of another class’s cultural production for the enjoyment and profit of them both. In that sense, what blinded Hurston no less than Hughes to the exploitative character of Mason’s relationship to them was their own need to use the folk culture of the Black masses to launch and sustain their own creative projects as writers.

That Hughes and Hurston were Black did not fundamentally alter the class nature of their expropriation of the art of the subaltern to fund their careers as artists. No Black and unknown bards ever received a royalty check from the books published under Hughes’s and Hurston’s names. What smoothed over this type of appropriation was Hughes’s and Hurston’s genuine empathy with the Black poor, and their racial vocation to give authentic voice to the subaltern through their creative work. Shared with Mason was an essentialist belief that Black mining of African American folk culture was inherently better and more legitimate than White efforts.

All of this took place because of the initiative of Alain Locke, as Mason’s frequent deferment of the details of future arrangements to him suggested. Indeed, this project was as much Locke’s as Mason’s idea, and he played a prominent role in its orchestration. After he returned from Geneva in late September, Mason consulted him before finalizing the arrangement with Hughes and the contract with Hurston. Thus, Locke was probably the source of Mason’s view of Hurston as primarily a worker instead of an artist, a view that reflected her relative status and his generally negative view of women writers. At the same time, Hurston was the only woman he was recommending for a quite lucrative fellowship to conduct her research over three years. He was as engaged as the writers in the collusion to appropriate folk culture for Hughes and Hurston’s purposes and accomplish his goal of advancing the scholarly and literary capital of the now-declining and increasingly disreputable Negro Renaissance.

After the contracts with Hughes and Hurston were finalized, Locke’s role with Mason suddenly changed. Locke became overseer of the artists he had brought into her stable. A regular feature of her meetings with him would be answering her prepared questions about “Langston’s financial situation,” Zora’s “academic status,” their progress or lack of progress on their artistic and research projects, and any other personal item Mason thought crucial to their obligation to stay focused on the work for which they were being paid. Also, Locke was consistently recommending new protégés, such as Arthur Fauset and Aaron Douglas, and escorting Mason to exhibits, such as the Haiti pictures exhibit at the Ainslie Gallery in New York. For this he received sums of money as “gifts.” Just as Locke was the first to be rewarded for his service to this system, he also was the first to feel the sting of Mason’s condemnation and disapproval if he or they failed to follow all of her suggestions or keep her informed of all of their activities.

A crisis that erupted between November and December of 1927 exemplified the costs of his new intimacy with Mrs. Mason. Locke had become increasingly preoccupied with Zonia Baber and plans for the “Negro in Art” in Chicago, because Carson Perie Scott, the prestigious department store, suddenly reneged on its commitment to host the art exhibit in its galleries. Baber wrote to Locke almost hysterical over the prospect that the “Negro in Art Week” might collapse if they could not find a place to exhibit the visual art, the core of the project. She pressured him for ideas and for his commitment to bring the Harlem Museum of African Art to Chicago to anchor the show. Indeed, as her correspondence with the director of the Art Institute shows, it was the prospect of exhibiting Locke’s African art collection that, in effect, persuaded the Art Institute director to find a place in the Children’s Exhibition Hall for the whole art exhibit just weeks before the “Negro in Art Week” was scheduled to open. While Art Institute curators were not enthusiastic about the African American art in the show, they enthused about the African art, given its esteem by European modernists. Although Locke had sought to separate the significance of his collection from that influence, the African art’s reputation in modernist circles helped secure the African American art exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago.

All of this was also good for the Harlem Collection, for it proved the Blondiau-Theatre Arts Collection was very reputable in the art world. Mason, however, was not pleased. She thought it was a bad idea to try and tour the African art collection before establishing a permanent museum in Harlem. Her turn to financing Hughes’s work was directly related to her sense that Locke was not serious enough in planning the Harlem Museum of African Art for her to continue to work diligently for its creation. She also was upset when he left for Chicago and did not tell her he would be gone as long as he was. On December 10, two days after she had arranged the contract with Zora, Mason attacked him for not giving her all of the information about his African Mandates speeches while he was abroad, failing to provide her advance copies of his speeches, and being so consumed with egotism that he played to the crowd in Chicago, instead of returning as soon as possible to New York.

The cheeky Locke hit back at her in a letter ostensibly expressing concern for her health, but ending with the hope that in her current illness she had regained full control of her mind. That infuriated her. “This is unbelievable that you could be so plain stupid. Nothing the matter with my mind only that physically I have to jump hurdles.” Locke was not stupid, but vindictive, and unable to resist taking a shot like the one she had heard about after Hughes’s first visit. In spite of himself, Locke could not avoid being subversive, even when it brought down more fury on him. By suggesting that she was going weak in the mind, he was demeaning her as an old woman and hence an intellectual inferior. She issued a lengthy reprimand and threat. “There is nothing the matter with my mind, Alain. It is my heart. You have shattered my belief—and you can not afford to lose it.”12 She was right. He could not afford to lose her support. All of his plans to advance the literary side of the declining Renaissance depended on her; and increasingly, even with the “Negro in Art Week” success, he was feeding her new visual artists as well. If he wanted to keep her support, he was going to have to find a way to keep her more satisfied, give up more authority to her in his decision-making, or at least appear to do her bidding, while he squirreled away opportunities and contacts that he kept only for himself. And if he failed in that maneuvering, he risked having the Negroes he introduced to her receive her money, power, and attention, without him.

Mason’s maternalistic approach to her patronage of Black artists was working its magic. Like paternalism generally, Mason’s caring for Locke and the artists came with an obligation to do her bidding exactly as she wished it or be dressed down like a child. Part of her power came from her ability to pit Locke and the artists against one another as if they were so many wayward children in need of discipline. Locke already had lost his prominence in her life, at least in part because of Hughes. As he sat in her parlor and listened to her reprimands, it could not escape him that she repeatedly compared his behavior to Hughes’s and found him less grateful. He had to listen to how Hughes was less White than he was, that Hughes was less interested in public flattery, that Hughes’s spirit was so delicate that she did not want Locke to disturb it by his attentions, the latter perhaps a veiled confidence to Mason from Hughes about Locke’s continuing advances toward him. In addition to having to listen to her insults, he had to face the prospect of losing control of a patron he had discovered and set up. As he looked around for someone to blame, his attention focused increasingly on Hughes, whom Locke felt was not sufficiently grateful to him for having put Hughes into this arrangement. The scheme Locke had designed to enhance his power was being turned against him, in part because Hughes had created conditions of patronage favorable to him and not especially to Locke.

This turnabout points to a central fact of the patronage situation Locke had set up: Mason was in control. While his subversiveness was always available, she was too aware of what her money and emotional support meant to him and too insecure to allow him the kind of independence he enjoyed with other patrons. As the others would eventually learn, Mason was ready at a moment’s notice to retract her money and support and abandon a too-independent Negro. Locke was going to have to do a better job of keeping her happy, while also keeping some of his autonomy. Finding that tricky balance was even more complicated with Hughes and Hurston in the equation. Now that she had Hughes, Mason dispensed with her earlier plans to fund the Harlem Museum of African Art and instead concentrated on a young Black male artist who was more attractive and more willing to be primitive than Locke. That was his real punishment for not having conducted the museum project as she had wished.

Locke was learning a powerful lesson. Mason was more adept than he at using people to get her way. Her money and her manipulative use of it allowed her emotional independence at the apex of her surrogate family. Her money allowed her to replace her godchildren when they were bad. Locke had been reduced from a potential director of a museum to an assistant to help keep Hughes’s spirit from being clouded by details. Hurston had just landed a contract for $200 a month when he was still trying to negotiate to get his job back at Howard. As 1927 ended, Locke, a supreme manipulator, had been played.

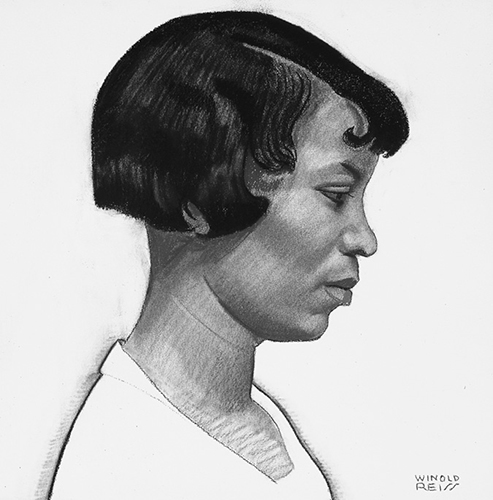

Zora Neale Hurston, 1925. Pastel on board. Winold Reiss. Photograph courtesy of the Reiss Archives. Copyright and permission to publish courtesy of Fisk University Galleries, Nashville, Tennessee.