37

The Riot and the Ride

Two days before Alain Locke trekked to the Museum of Modern Art in midtown Manhattan on March 21, 1935, to enthuse over Benin bronzes and Ife masks, Negroes ninety blocks northward had smashed plate-glass windows, fought police, and looted the trinkets of another decadent civilization. Two Black acts—the visit and the riot—with apparently nothing in common proceeded almost simultaneously. Locke, a professor, returned repeatedly to the temple of high modernism trying to claim an art tradition all but destroyed by European colonialism, then hijacked by European modernists, and now claimed as the intellectual property of American curators and art historians like James Sweeney and Robert Goldwater, while Harlem’s African American residents destroyed $2 million worth of property after it massed outside of a Kress’s Five-and-Ten because of rumors a young Puerto Rican thief had been mercilessly beaten by store clerks. Moving like a ragtag army, the unemployed—and underemployed—hurled rocks, broke through storefronts, and burned everything they did not take on 125th Street. So often dark and depressing in the evenings of the Great Depression in comparison to well-lit mid-Manhattan, Harlem lit up like New Orleans during Mardi Gras. Yet this was one party Locke missed. No mention of it disturbs his correspondence. No commentary exudes from this usually loquacious cultural critic as to why Negroes living at starvation levels with no exposure to high aestheticism were destroying every symbol of White commodity civilization in A-train New York.

The irony was tragic, but also comic, as Locke’s concerns would have seemed ridiculous to the poor Black people exiting Kress Five-and-Ten Store windows with hot combs, lightening cream, and pen knives. Not only poor, Black unemployed, but also highly employed White aesthetes would ask Locke, why bother? Or as Irving Howe famously said to Ralph Ellison, the “Negro is not metaphysical.” Locke, however, had tried to establish a Harlem Museum of African Art in the 1920s to no effect to show the Negro that she and he were heirs of a great civilization and thus subjects of the world. But he had failed precisely because neither Negroes nor Whites saw African art and high aestheticism as a means for Black people to rise up again. Instead, the riot dominated the front pages of New York newspapers and cast the Negro as something else—a poor, hungry, but suddenly angry product of American civilization, now bent on tearing it down if she or he could not find justice within it. Unable to confront the contradiction head-on, Locke avoided the burned-out stores, the broken plate-glass windows, and the disheveled people stumbling around aimlessly yet angrily on 125th Street, Black people who knew they had been misused by New York and now decided to burn it down. Historians say the riot marked the end of the renaissance he had announced ten years earlier. Negro art was threatening to become little more than an exquisite corpse, an archived artifact seen only by White people in a mid-Manhattan museum.

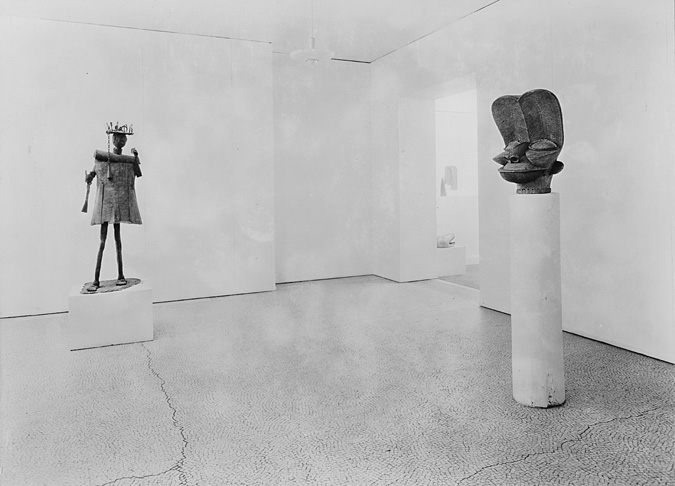

It is worth taking a moment to see what Locke saw when he visited the Museum of Modern Art. He entered a spare exhibition space that from the first room taught the lesson he was trying to teach the world and Negroes with African art, that a dialogue existed between art and the Black subject in such spaces, when the horrific historical cacophony of colonialism, racism, and decline through Western contact was silenced. In a bright, white-walled space, a sculpture of a thin, angular, but powerfully armed African stood on one side of the twenty-five-foot-square room. The figure was the famous iron Dahomey Gu (war god). Opposite this spectacular figure was the most aesthetically radical representation of a human head in the show, a huge mask (tsesah) from the Bamileke people of late nineteenth-century Bamendjo, Cameroon, that showed why European modernists seeking a doorway to conceptual art seized on African art in the early twentieth century. For this mask contradicted all of the Renaissance notions of how to represent the head, turning eye sockets into bullets and topping off the head with an uplifting fan-like structure that seemed part antennae, part crown. Yet here, too, was the face, the visage, of a man, who was imbued with the Spirit—and joyful. He was not sad. He was in control of his world even as he acknowledged the control of the Spirit. He was alive with possibility, not beaten down by others’ oppression. He was free, the creation, one could imagine, of the free, warrior-like figure on the opposite side of the room, facing his destiny with confidence and hope. Here was the dialogic relationship Locke had hoped to create in the Harlem Museum of African Art—and perhaps forestall the descent into darkness the 1935 riot represented to him—by allowing the twentieth-century Negro to gaze on the ancient Negro and the conceptual art mask he had created.

Installation view of the exhibition, African Negro Art, March 18, 1935, through May 19, 1935. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

But Harlem Negroes were not in the room with Locke. They were picking up glass and the remnants of their tattered lives seventy blocks north of this museum, where a White man, James Sweeney, had brought to life Locke’s message of a self-sufficient African manhood. That message would be mainly consumed by White not Black Manhattan, since Locke had failed in his attempts to teach the masses of Blacks to think aesthetically about their environment, about their possibilities. Where Locke felt free in this White block of aestheticism, he was sociologically incarcerated in Harlem, where the reality of the failure of the Negro Renaissance was scrawled on the now-boarded up and heavily policed built environment. But there was a message up there for Locke as well. In the messy, broken-glass environment of riot-torn Harlem, the Negro of the twentieth century was at least in dialogue with her environment, speaking back through violence to a built environment s/he had not built, but was now oppressed by despite the vision of the Black metropolis Locke had created in “Harlem.” The riot was just as creative an act of exhibition as MOMA’s, except it was the “ashes” response to oppression rather than the beauty he wanted. Yet so addicted was Locke to the vision of African identity represented in this exhibit that he could hardly tear himself away to trek back up to Harlem to stay at the YMCA, where he was allowed to stop in New York overnight. Locke could not escape the new reality: his vision of an aestheticized New Negro who turned anger into art was no longer widely credible. Up to 1935, Locke had acted as if he did not have to account for the “left behinds.” Beauty mattered, not the ashes.

Now, however, in March 1935, a Black subaltern people no longer accepted being silent sufferers. Stripped of the right to picket stores that took their money but refused to hire them as employees, stymied by bureaucratic red tape from receiving decent health and social services, a rebellion had erupted with such a clear sense of outrage at the living conditions of Harlem that even Time magazine called a protest. But protest was something Locke instinctively avoided. Feeling that protest created the most degraded forms of art possible, he had eschewed and criticized the trend toward “protest” and “proletarian” art in the early 1930s. He continued to argue that art was an alternative to protest, and the only true art was that which refused to voice the harangue of the mob. But as he soon would learn, protest—even violence—against the injustices of Black life did matter, and they mattered more in the 1930s than they ever had. Protest, violence, and rebellion were things he had not yet accounted for, nor the possibility that they could, if he were not careful, derail his entire cultural strategy and make it—and him—irrelevant.1

It was not the case that Locke was unaware of the sociological, economic, and political dynamics that produced and sustained the African American ghetto. As early as his Race Contacts lectures in 1915–1916, Locke had developed one of the most sophisticated theories of race and space in American intellectual history, one that outlined how “restricted status,” as Locke had put it, was marked in American society by assigning minorities, such as the Negro and the American Indian, to “separate” spaces—the ghetto for the Negro, because his labor was needed close at hand by White society, the reservation for the Indian, because his labor was not needed. That was another reason why Locke had grouped the two at the Minority Problems Conference in 1935; they were linked by the “separate sphere” spatial ideology that defined how they were controlled under what amounted to American “imperialism.” Although the papers on “nonviolent” and “militant” activism presented at the conference are now lost, it seems likely that some mention of the recent Harlem riot would have been made.

The problem for Locke was that he could not put together, yet, the sociological and the aesthetic analyses of race when it came to something like the postmodern phenomenon of a rebellion against the commodities of mid-twentieth-century America out of reach of the Black poor in Harlem in 1935. More broadly, Locke could admit that social conditions were important and crucial, but he could not allow them to invade and distort the true purpose of art, which was beauty. That was the crux of his dilemma. How could he relate the pursuit of beauty to the pursuit of justice in Black America without reducing the former to the latter?

From 1930 to 1935, Locke had refused to give in to the pressures to make that kind of reductionism in his literary and cultural criticism. In that sense, his advocacy of the New Negro so far was bracketed by two reductionist approaches to art—what might be called the Queer Black aesthetic of the late 1920s and the proletarian art and literature of the 1930s. The shift from the 1920s emphasis on the beautiful Black subject to the 1930s championing of the angry Black subject was disturbing for Locke. But in fact the two had much in common, something Locke ultimately vehemently opposed. They started from the premise that art should represent its subjects according to some ideal, usually connected to the agenda of shocking or dethroning or destroying the hegemony of the bourgeoisie. Even during the 1920s, Locke reacted against what Bruce Nugent, Wallace Thurman, and Langston Hughes were doing—shackling, in Locke’s mind, the agenda of a young Black art production to celebration of the “strength of the black gay spirit” rather than the production of great art. Locke’s commitment to art as the embodiment of the diversity of Black humanity made him wince at attempts to achieve revolutionary solidarity through art, the direction in which the arts of the 1920s were headed. That seemed more like dogma than art to Locke, even though at times these movements produced exceptions that transcended such dogma.

By the mid-1930s, the poetry of Sterling Brown, Richard Wright, and Frank Marshall Davis, the plays of Samuel Raphaelson, and the newly militant writing of Langston Hughes in Scottsboro, Ltd. began to interpret the Great Depression and the disproportionate suffering of Blacks under it as evidence that the American capitalist system had to be overturned if Blacks were to achieve freedom and justice in America. Locke, however, was not very enthusiastic: “some of the younger Negro writers and artists see this situation in terms of what is crystallizing in America and throughout the world as ‘proletarian literature.’ What is inevitable is, to that extent at least, right. There will be a quick broadening of the base of Negro art in terms of the literature of class protest and proletarian realism. My disagreement is merely in terms of a long-term view and ultimate values. To my thinking, the approaching proletarian phase is not the hoped-for sea but the inescapable delta. I even grant its practical role as a suddenly looming middle passage, but still these difficult and trying shoals of propagandist realism are not, never can be, the oceanic depths of universal art.”2

Locke was not free of bias in these judgments. He had adopted the strategy of art as a means of social change in the 1920s as an alternative to protest. He resented protest literature, as if it was a contradiction in terms. In addition, Locke was ambivalent about the Black masses and any literature that focused too exclusively on the anger of those Black masses. Fundamental to his approach to literature prior to 1936 was an elitist conception of Afro-American culture that was created by a cultivated “Talented Tenth” of Black writers who mined the folk and blues traditions to create what was inevitably “fine art.” But the folk that Locke loved were the romanticized and aestheticized folk of the Harlem novels—not the angry, society-destroying Black masses of 1930s agitprop literature. For Locke, Afro-American cultural strategy in the 1920s was about being used to bring harmony between the races and providing an opportunity for gradual reform of American attitudes. By the 1930s, literature carried as subtext a confrontational approach to social change in America—something Locke could not stand.

Subtly, slowly, Locke began to ameliorate his antipathy to protest art after the 1935 riot. Interestingly, Godmother, a fierce anti-communist, suggested he get tickets to see two new plays by Leftist playwright Clifford Odets at the Longacre Theatre. That she sent him to these radical plays gave him maternal sanction to temporarily shed his usual class antipathies and begin to refashion his views as a critic of the new American aesthetics. “John [Mason’s Black chauffeur] drove me over to the theatre,” he wrote her. “The audience was small—but over-enthusiastic—not entirely from the normal reaction to the plays—but because they were partisans of one or another left-wing movements. It had the effect of a claque, and set me leaning backwards in the other direction.” Yet Locke was open to what happened on stage, even if he was not as “enthusiastic” as the crowd. “Odets is a coming force in American drama and our social life—but he is over-anxious about his effects, packs them in too thick, and gets melodramatic on the slightest provocation. … There is vital new material here—and a living purpose beyond the stale ones of amusement or sophisticated analysis … an invigorating slap in the face of our bigots and charlatans and exploiters.”3

To the first play, Odets’s Till the Day I Die, Locke reacted in his typical way to 1930s agitprop theater: it was in too much of a hurry to convey its message and not focused enough on how accurately or how well it conveyed such messages. “I wish Odetts [sic] knew his Germany better—his Nazi types are grim caricatures … the hand chopping was too premeditated—(Odets wanted the audience to know it was coming so as not to miss it) as if they could? And things like that all through. Still, I wonder who could be neutral about Hitler and his gang after seeing the play—they ought to be sentenced to see it themselves.” Key to his critique was his continuing opposition to the way that such plays did not pay attention to what made art interesting—the style, energy, and deliverance of the message. He had heard that “Till the Day I Die had been played once recently by a radical but amateur Negro players’ group under Rex Ingraham (who played Stevedore) and that Odets had said ‘They made a new play of it.’ Of course, what they added was conviction, naturalness and spontaneity.”4 They had put soul in an otherwise soulless play.

Odets’s other play, Waiting for Lefty, touched Locke more. “To me the most effective scene was one where the superintendent of the hospital is trying to wash his hands like Pilate over the intrusion of politics into his hospital and the loss of a patient in an operation because a relative of a higher-up must get this chance to enhance his reputation. This is real drama, because with the operation off stage, it leaves something for your imagination to do. Other scenes are too packed with realism and the actual message—so they either go preachy or melodramatic.” The play narrated his struggle to accept the legitimacy of protest. But Locke was quick to add, perhaps mindful that Mason had recommended these performances to him, “Mind you, I am not belittling these plays—they are worth a score of Broadway successes and stale formula dramas. Only Odets and his theatre must grow up—and if they grow up unspoiled and uncommercialized they will be the American theatre of the future.”5

“Leaning backwards in the other direction” was the memorable phrase from his letter to Mason, and it captures the whole problem. The art of the 1930s demanded that he engage with the reality of those suffering more than him. Confrontational aesthetics existed because the audience had to be shaken in order to break out of the blinders that bourgeois status imposed on the middle. For some time, he knew he had to come to terms with this art, with the dramatically changed reality of Black life outside of his Howard citadel, outside of his imagination of Harlem as a Mecca, as his attempt to provide a balanced assessment in this letter to Mason shows. He opined that once the art “grew up,” it would become “the American theatre of the future.” But it was Locke who had to “grow up” and create a more adult version and less romanticized view of Black social reality in the Great Depression. Locke had to change his orientation, but he had been unable or unwilling to do it.

Locke realized instinctively that the riot opened up a new racial landscape of interest and commitment of resources by the White establishment. By destroying property, rather than attacking White people directly, Blacks had brilliantly seized upon the one thing that had valuation in capitalism. The riot that destroyed a chunk of New York real estate brought Black people to the attention of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, no less than President Roosevelt, and Locke had in his desk drawer a proposal for something they could do to address the situation and perhaps keep Black people from doing that again.

Prior to the riot, Locke had penned a brief proposal for an art center under which to house Negro visual and performing art activities, both creative and educational, in Harlem. Aware that in the aftermath of the riot, New York mayor La Guardia had set up a commission to study the conditions behind the riot and that E. Franklin Frazier, his Howard University colleague, headed up the research team, Locke updated his proposal for a Harlem Cultural Center as one way the city could try and make beauty out of the ashes of the Harlem race riot. In May 1935, he sent to Brady a brief “memorandum” for “A Harlem Center of Culture” to be installed in the YMCA building on the southeast corner of Lenox Avenue and 124th Street—one block from the center of the rioting. Interestingly, Locke made no direct mention of the riot in the proposal, but pitched it instead as a response to the “lack” of “facilities for art, music, drama, and adult education” in the “Harlem community” even though there was “much latent talent” there that needed “only favorable opportunity for expression.”6

Aware that the riot was being interpreted as a violent expression of discontent, Locke alluded to the events merely by stating the obvious: “The development of this talent will add to the happiness of the people.” Here, the idea offered the palliative that was often recommended in the aftermath of urban riots: “Such a center would be a spiritual force of the community” and allow “the best efforts of its gifted members” to be “displayed for the encouragement and inspiration of all.” Such a sacred space would germinate a “‘vision splendid’ to encourage and stimulate the best in the community” and “congregate those who have distinguished themselves by praiseworthy achievements in the arts to encourage and inspire greater numbers of their fellow citizens.” In such a center, the “master spirits of the Negro” would “inspire” the rest of the Negroes to “noble endeavor” and become “what Athens was to Greece, what Paris and Vienna are to Europe—greater centers of racial culture, racial aspiration and racial achievement.” Not surprisingly, Locke recommended that the “director or Executive Director” of the Center be a Negro, selected by the board of education “because of his sympathy and vision to see the illimilable [sic] possibilities of the project and ability to conduct the center effectively.” Clearly, Locke saw himself as such a person. Just as clearly, Locke articulated the older, cathartic view of art that he had proposed for much of his career as a Black aesthete and not the more militant view of art as a weapon of social upheaval as articulated by Augusta Savage, Romare Bearden, and Charles Alston.7

Tellingly, when a Mr. Rivers in the mayor’s office suggested having hearings as part of bringing the proposal before the commission, Locke demurred. “I think this ill-advised,” Locke wrote to Brady, “unless it is absolutely necessary. A committee of representatives ought to take the matter either straight to the Mayor, knowing in advance that the Investigating Committee will favor it; or the plan should come through as one of the Committee’s recommendations reached in their deliberations. Why not let the Committee have the credit! Getting the idea across is the main thing.” Locke urged Rivers to take the “scheme” to the “Investigating Commission chairman.” Locke even spoke directly to “two members of the Committee” and suggested a “remedial finding urging immediate prosecution of a W.P.A. housing scheme for Harlem” that might include the cultural center as an elevating and humanizing part of the overall redevelopment of Harlem.8 For years, Locke had been quietly feuding with Augusta Savage over her and other Harlem artists’ control of art educational efforts in Harlem. He had been frustrated, along with Miss Brady, with art-education activities controlled by Ernestine Rose, the White librarian at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library in Harlem. Locke did not want a public hearing where competitors like Savage or Rose could weigh in as being the legitimate custodians of such an effort in their veritable backyards.

Indeed, Rose had offered her own proposal to develop a “program of the extension of the library plant” to take advantage of the attention the riot had focused on the anger of the Black masses in Harlem and to suggest that art education might be a way to ameliorate local tensions. When the perspicacious Locke learned of her plan, he conceded that Rose’s annex “could very well be housed in one end of the Community Center, although the management ought to be distinct.” In other words, her project could be “housed” in his center if the “management” of the two entities was kept “distinct,” because he and Mary Beattie Brady had already crossed swords with Rose. In order to establish his center and his appointment as its director, Locke would have to displace those arts managers resident in Harlem, and he did not want them getting wind of it before it was a fait accompli.

The committee headed by the rigorous, and critical, E. Franklin Frazier did not decide that a “Harlem Center of Culture” should be one of its main recommendations to address the systemic problems of poverty, unemployment, chronic and rampant disease, dirt, filth, and crowding in housing that plagued the area. And as Locke tired of struggling to advance his version of aesthetic education in an inhospitable climate after the riot, he longed to escape to Europe. Right after offering his proposal to the Harlem Commission in June 1935 and having it tabled, he left on a six-week tour of Paris, Brussels, Zurich, and Vienna, returning from what had happened over the summer in Harlem.

There was the rub. As a transnational, trans-urban cultural worker, Locke lived everywhere and nowhere. Of course, there was the upside to that kind of cultural mobility—in the Harlem Renaissance, he had brought together the German artist Winold Reiss, the West Indian writers Eric Walrond and Claude McKay, the French colonial critic Rene Maran, and other “most gifted” citizens of their respective cities and nations, to make Harlem into a symbol of the “vision splendid.” But like other transnationals, Locke was not deeply inserted in the local. Locke’s imaginary was diasporic, and in his letters to Mason that spring, it was the Italian-Ethiopian War and its threat to the Ethiopian homeland of Black Christianity, not Harlem, that consumed him. Mason chastised him for his need to escape Europe in ways he said “hurt.” He admitted, “I must be made to realize that someday I must seize the courage to get a favorable place to work on my own ideas during the one free period in the year I have.” He needed to finish his Bronze Booklets and advance his center idea at home. But his double bind reasserted itself every summer. “The only way of being reasonably comfortable would be to find a small cottage somewhere—and then the trouble of companionship would begin. The resorts for Negroes are entirely impossible—privacy is out of the question.”9 There was no place in America where he could be both Negro and queer—except, perhaps, in Harlem, if he could establish his center and some permanent income there. But that didn’t happen, in part because Locke was not embedded in the daily living conditions of the community he wanted to resuscitate.

Returning home, however, Locke discovered his center idea might be in play again. Paul Kellogg, the editor at Survey Graphic, came to Locke with a proposal. Frazier had finished a preliminary report while Locke was in Europe and submitted it to Mayor La Guardia for comment, approval, and publication. La Guardia demurred. Kellogg then became involved when Oswald Garrison Villard, the perennial Leftist and commission member, had offered an article on the report’s conclusions to Survey Graphic, and then withdrawn it when Kellogg circulated the draft through city departments for review prior to publication. Kellogg needed someone to write a “balanced” article on the subject and repeatedly asked Locke to do it. Rather than hire Frazier to do the article presenting the report’s findings to the public, Kellogg wrote to Locke in January 1936 asking if he would be willing to study the report the Commission had made, meet with city commissioners criticized by the report, and write an article for a popular audience that would set the record straight.10 Locke demurred, citing the pressure of work, which included trying to get the first set of Bronze Booklets published. But Locke inquired whether the mayor might be interested in creating the Harlem Cultural Center he had earlier proposed. If the mayor did create such a center, Locke could have a place where he could plant all of his efforts to make Negro literary, visual, and theater arts an engine of change for the Black community in Harlem.

But in March, a challenge emerged to Locke’s whole philosophy of racial renaissance when Meyer Schapiro, a fiery, Jewish, Trotskyite professor of art at Columbia University, published an article, “Race, Nationality, and Art,” in the March 1936 issue of Art Front, the radical monthly journal of the Artists’ Union. In that article, he stated: “There are Negro liberals who teach that the American Negro artist should cultivate the old African styles, that his real racial genius has emerged most powerfully in those styles, and that he must give up his effort to paint and carve like a white man. This view is acceptable to white reactionaries, who desire … to keep the Negro from assimilating the highest forms of culture of Europe and America. … But observed more closely, it terminates in the segregation of the Negro from modern culture.”11

A year earlier, Locke had been going to MOMA in part to encourage Black artists to seize on African art as inspiration. Locke was not alone. Several such artists, such as Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis, were also going to MOMA, although without acknowledging Locke as their source of inspiration. Now Locke had a White radical intellectual criticizing his views—without mentioning him by name—suggesting that such advice was tantamount to self-segregation. More devastating, this critic repudiated the notion that something like a racial art tradition existed at all.

Schapiro was the most spectacularly original and brilliant young art historian in America. “Race, Nationality, and Art” was mainly an attack on the German art historical tradition that used race and nationality to characterize world art as falling into neat national or racial traditions that embodied the particular psychologies of those nations or peoples. Schapiro argued that what were thought of as enduring psychological traits in national traditions were mere conventions of how art history had been studied and lacked any scientific basis. He claimed such notions of national or racial proclivities in art inevitably led to Nazism, a view confirmed, it seemed, by German art historians’ support of the Nazis when they came to power in Germany. Schapiro was building an alternative approach to art history—that of analyzing art in terms of its social basis in its own time and suggesting that great art usually emerged from class and other conflicts in a society or civilization, such that the tensions, disconnects, and discontinuities of a social order erupted in a work of art and gave it its distinctive style. Schapiro was dismissive of all trans-historical factors in shaping a work of art, and he categorized race as one of those factors, a dangerous myth and analytical anachronism that had no place in a “scientific” art history of modern art.

Schapiro’s attack on Locke was part of Schapiro’s broader reaction to the changing landscape of American Marxism. For years, American Marxists had argued that if Black artists produced a racial art, they were ethnic chauvinists driving a wedge between White and Black workers and undermining socialists’ efforts to foster class-consciousness among American workers. But building on his theory of socialist culture in his 1925 speech, “The Political Tasks of the University,” Stalin encouraged ethnic nationalism within the Soviet Union and ethnic cultures in the union republics in the 1930s as not contradictory to socialism. Stalin’s form of Soviet cultural pluralism captured in the line “socialist in content, national in form,” however, was anathema to Schapiro and other Trotskyites in the United States, who wanted to keep Soviet cultural pluralism out of US socialism. But it was already happening, to his chagrin. By 1935, faced with the rise of Hitler in Germany as a threat to the Soviet Union, the International Seventh Congress of the Comintern declared a “People’s Front Against Fascism,” in which communists would enlist liberals and progressives in alliances with communists in the fight against fascism. These two developments—the acceptance of cultural pluralism and the welcoming of liberals into the Radical Left circles of culture in the mid-1930s—led the Communist Party USA to welcome “Negro liberals,” as Schapiro called them, into its summer camps, to lower criticism of their racial arguments, and to make celebration of African American culture a key part of the “revolutionary” education for workers in the Party. Suddenly, the ideological control that Schapiro and others like him had had over the socialist art movement in the United States by claiming that any assertion of a distinctive culture produced by Blacks in America was tantamount to “chauvinism.” In coming down on Locke, Schapiro saw himself as turning the White and Black proletariat away from the worship of false idols, such as race, and directing them toward the monotheism of Marxism as the one true and new religion—despite that that “religion” had evolved into something quite different in the Soviet Union.

Locke’s argument was actually subtler than Schapiro’s would allow. As Locke had argued in “Harlem” in the 1925 Survey Graphic, the New Negro was not a fixed identity, but a work in progress being constructed by modernity. “Hitherto, it must be admitted that American Negroes have been a race more in name than in fact, or to be exact, more in sentiment than in experience. The chief bond between them has been a common condition rather than a common consciousness; a problem in common rather than a life in common”—a “body-in-pieces” that needed a “fiction,” the New Negro, an invented “I” to pull its pieces together into a coherent, mature identity.12 The function of literature, art, the theater, and so on was to complete the process of self-integration through visual and literary art and produce a Black subjectivity that could become the agent of a cultural and social revolution in America. Promoting the study of African art was not his attempt to take the modern African American back to a pre-American romantic past, but to anchor a progressive “transformation that takes place in the subject when he assumes an image,” as Jacque Lacan put it, teaching the “child race,” as Locke once put it, that it was the modern heir of a great tradition. Modern Black art would do something that ancient African art never had to do—synthesize a disparate body-in-pieces of the Negro race, drawn by the African slave trade, the Diaspora and slavery, and modern segregation into a new whole. And to do that required a Moses—a role that Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Marcus Garvey had each seen himself as performing, but that Locke saw himself taking up through art, not economics or protest politics. Blacks needed to form a stronger identity in order to join any larger collectivity called the American working class, but some on the Left in the 1930s viewed that stronger racial identity as a threat.

Harold Cruse characterized this type of conflict as intrinsic to how Jewish intellectuals treated African American cultural production during the 1930s.13 But not all Jewish intellectuals and even art historians approached Negro culture and African art as Schapiro did. Another Jewish art historian, born a year after Schapiro, was Viktor Lowenfeld, who fled to the United States two years after Schapiro’s article was published and accepted a position teaching art at the Hampton Institute, the Negro college in Virginia, in 1939. Unlike Schapiro, Lowenfeld encouraged his art students to develop an art that reflected the particularities of the Black experience in the South and the urban North. In part because of his firsthand experience of Nazi terror, John Biggers, his most famous student, recalled seeing Lowenfeld break down in tears when he learned his family had been massacred by the Nazis—and theorized that Lowenfeld’s own experience with suffering and oppression conditioned him to encourage his students to use their art to confront how Blacks lived and coped with American oppression, rather than run away from it in their art. According to art historian Alvia Wardlaw, “Lowenfeld actively used Hampton’s collection of art from Africa and other cultures. It was the African works that most sparked Biggers’ imagination. He recalls that the first time he saw these sculptures he was repulsed and could not understand why Lowenfeld ‘wanted us to look at that ugly stuff!’ ”14 At the time Biggers could not fully appreciate the bridge to African heritage that former Hampton student William Sheppard had hoped to build by donating Juba and Central Kongo art to Hampton.

But Lowenfeld insisted on exposing his students to these objects, believing that in studying them they would discover a direct and palpable link with their African heritage. As he expressed his art philosophy in the Hampton Bulletin of 1943, “Culture has never developed without unity of life and art. [Teaching art is only justified] if it makes a definite contribution to Negro life and culture, in spreading art into community life, homes, and schools, and in making the campus art conscious.”15 While Locke and Lowenfeld would not meet until the 1940s, they were kindred spirits despite differences of heritage because both believed in the psychological healing of deep explorations of heritage and identity.

Lowenfeld’s perspective developed out of a direct experience of the Holocaust. Schapiro’s attitude emerged out of his experience of America as a reformed Jewish immigrant boy, who attended Columbia during his adolescence and found in art history, and especially Marxism, a way to escape what many of his generation felt was a stifling Jewish ghetto in America. Schapiro found in Trotsky communism a space for the reformation of ethnic identity into a higher identity, a kind of cosmopolitan equality antithetical to religious or ethnic heritage. Even Ralph Bunche, like Schapiro, believed that a Marxist revolution based on class would wash away racism and the need for counter-identities such as Locke promoted. Marxism and modern art were signs of freedom; race and religion signs of backwardness. Why would anyone want to go back to that, Schapiro must have thought.

But while Trotskyite and even Communist Party cells, camps, and parties were freer, more diverse, and more sexually open than conservative or liberal political communities, a racial intellectual division of labor also existed in Communist USA circles. Jokes like “You bring the schwartzes, I’ll bring the booze” reveal a sense that Blacks were the bodies needed to authenticate the enterprise, not the minds who would guide or refine the enterprise of creating this new world of post-capitalist America.16 As the historian of African art Ladislas Segy pointed out during a visit to his gallery in New York, all three of the architects of modernism were Jewish—Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Albert Einstein.17 Blacks, in other words, were latecomers to modernism—the intellectual proletariat to follow in the footsteps of the new Moses.

A generational revolution was also undermining Locke’s program in the 1930s as much as ethnic competition between two oppressed minorities. Two months after Schapiro’s article appeared, Locke received a mimeographed manifesto from the Harlem Artists Guild announcing a policy of “non-cooperation” with the Harmon Foundation. The Texas Centennial Exposition had planned an exhibition of work by Negro visual artists and had asked the Harmon Foundation to help organize the event. The Harlem Artists Guild was also invited to participate. But when the Guild circulated its memorandum of “non-cooperation” with the Harmon Foundation, it dashed the Foundation’s plans to “organize” the Negro exhibition. Locke was livid. To Miss Brady, he wrote:

I was going to write you that I could give some time, while in New York proofreading, to your plans for an art show and to the scenario of the movie. But when you read the enclosed memorandum of the Harlem Artists Guild, which I just received in this morning’s mail, you will, I think, join me in a reaction of protest and disgust. I really don’t see much use in putting out time and energy disinterestedly in behalf of folks with so little sense of appreciation and gratitude. All the more so, I imagine, in your case. I had no wind of this, though I am not terribly surprised. I had a casual talk, recently with Augusta Savage, who was soliciting my interest in her forthcoming art festival week. She gave no indications of this attitude or I would have rebuked her. You may still consider going on, but I really don’t see how a show could be very successful in the face of such a group boycott. To me, the main motive seems to be new-found independence because of the W.P.A.’s support. That would be alright if they had discharged their obligations to the foundation and admitted the helpfulness of the past. I don’t want to be too cynical, but I would wager that three months after the government stopped its gratuities, most of them would be knocking at your doors again with their hands out as usual. I would challenge their position publicly, but they don’t fight fair, and I am too tired and disillusioned to take them on.18

The Guild’s memorandum was an artistic declaration of independence that stated:

The Guild, comprising the majority of Negro artists in Greater New York and numbering in its ranks some of the foremost Negro artists of the country, is convinced that the Harmon Foundation does not serve the best interests of the Negro artist. We feel that the Harmon Foundation’s past efforts to advance Negro art have served the opposite purpose by virtue of their coddling rather than professional attitude toward the Negro as an artist. Basic in the ill direction of the Harmon Foundation’s efforts has been the fact that they are not a recognized art agency and, possibly for this reason, have presented Negro art from the sociological standpoint rather than from the aesthetic. The selection of the Harmon Foundation as entrepreneur for the Negro artists in the instance of the Texas Centennial Exposition is a clear example of how insidiously the Foundation has become an arbiter of the Negro artist’s fate through the mere fact of its original, perhaps well-intentioned, philanthropy on the part of an organization which is incompetent to judge art except on a racial basis that we take this occasion to announce our reasons for not cooperating with the Harmon Foundation in this particular instance.19

Eleven years earlier, Locke had written in The New Negro: An Interpretation, “Tutelage of any sort is rejected in favor of the New Negro wanting to go it alone.” Now, he was angry because the Harlem Artists Guild rejected the Harmon Foundation’s tutelage. But he saw this as a swipe at him as “an arbiter of the Negro artist’s fate,” since for several years he had served as a guest curator and judge of art in the Harmon Foundation exhibitions. Brady seemed less upset, out of weariness perhaps, with the memorandum and less convinced that it was the work of Savage. “Frankly I do not know who the malcontents are definitely as they do not come out in the open. I have been under the impression that Miss Savage had a very co-operative feeling, also Mr. Alston and Mr. Aaron Douglas. None of them have ever come out and told us to our faces that they don’t like us. In fact Miss Brown has been a connecting link and she has had very definitely the feeling that they were very friendly disposed.”20

But the Foundation should have seen this rebellion coming. When Brown had visited a Mrs. Pollak, who had control of many of Augusta Savage’s and other young Black artists’ artwork to coordinate exhibiting in Texas, Pollak informed her that the WPA would do its own installation at the Dallas Centennial and would not lend any of Augusta Savage’s art to the Harmon Foundation. When Miss Brown expressed surprise, she was told to meet with Holger Cahill, the director of the Federal Art Project, in Washington, D.C. When she did so, Brown found “Mr. Cahill was exceedingly indifferent and finally stated that the real reason behind their unwillingness to cooperate with us was that the artists themselves did not like to exhibit through the Harmon Foundation.” The memorandum from the Guild merely concretized a brewing attitude of self-determination by Black visual artists who were tired of having to go through Brady and Locke and the Foundation to get their work seen. Brady must have known of these rumblings of dissent before the Guild letter arrived, and if she did not, she was a quite a bit less astute in this area than she showed herself to be in others. Nonetheless, Brady was not in a mood to fight. “I dislike argument of an unnecessary nature and I certainly do not want to undertake anything that is not helpful,” Brady confided to Locke.21

Locke was correct about one thing: the emergence of the W.P.A., founded that April 1935 with Holger Cahill as the director of the Federal Art Project, made “non-cooperation” with the Harmon Foundation possible. Cahill had moved aggressively to make the WPA a player in the American art world, especially by employing African American artists, some of whom, like seasoned artists Charles Alston and Archibald Motley, received employment checks for work as artists for the first time in their lives. And in Harlem, artist-entrepreneurs like Augusta Savage seized on the WPA to secure employment for her favorite artists and to lobby Cahill and others to create what local artists had wanted for years—a Harlem Community Center run by artists. With that new lease on government money, Harlem visual artists were independent of the kind of private patronage the Harmon Foundation offered. That independence extended to subject matter, as the WPA allowed a wide range of freedom to artists to explore political themes like lynching, poverty, urban decay, rural decline, and working-class life, more politically edgy work than the Harmon Foundation favored. And the WPA allowed a degree of integration the Harmon’s segregated shows did not foster, bringing together Black artists to work with and study with more established White artists who also needed a WPA paycheck to live. Clearly, the WPA was a better patron, despite Locke’s belief in loyalty to the Foundation that had secured earlier recognition for Black visual artists. There was little loyalty to loyalty in the 1930s.

Locke and Brady refused to acknowledge, though, the simmering resentment that had existed for years toward the Foundation. While the Harlem Artists Guild exaggerated how much Black artists had to “bow and scrape” to get the support of the Harmon Foundation, some like William H. Johnson felt the Foundation was not aggressive in selling his work (something frankly they were ill-equipped to do) and that the Harmon Foundation was cheap. It charged unemployed artists to frame their work and refused to return it to them until they reimbursed the Foundation even though the framing was only done to exhibit the work for the Harmon Foundation! Harmon was losing position to the WPA, because the Foundation refused to employ artists, again, something it was not equipped to do on a large scale. But that was what Black artists needed—not tepid exhibitions that sold no work. Even Locke was never employed by the Foundation for his labor. The Foundation embodied the old Christian benevolent idea that Blacks were so downtrodden, they should be grateful for any assistance; but that attitude was rapidly disappearing among “New Negro” visual artists of the 1930s, even if Locke did not like their criticality toward his allies.

An intriguing subtext also existed to this “rebellion” that Brady revealed in her letter to Locke.

Mr. Schomburg was in the office the other day and he volunteered the suggestion that several years ago when a young man named Bearden wrote an article for Opportunity on the disadvantages of Negro artists associating with the Harmon Foundation, that it was his understanding that Claude McKay had written the article. I always find it difficult, as you know, to get Mr. Schomburg right down to the actual point. … He said he would get his ear to the ground and give us the advantage of any information he was able to dig up.22

That article had been written by Romare Bearden in 1934 to complain about the Harmon Foundation not being a legitimate art institution and putting on shows that contained very weak art by Negroes alongside the more sophisticated. It had been the first public rebuke of the Harmon Foundation by a Black artist and had contributed, perhaps, to Brady’s decision to back away from hosting expensive exhibitions for “ungrateful” Black artists. Interestingly, Brady did not readily believe that McKay had been behind the Bearden article, because McKay “had received a recognition from the Harmon Foundation a number of years ago, later applied to us for a grant to continue his research and study in some foreign country. … We gave him all the helpful suggestions we could.” But they did not give him any money! Here again was the Harmon conceit—penniless artists like McKay ought to be grateful for “helpful suggestions” when what they needed was cash. “It has always been my understanding that as far as he [McKay] thought of us at all it was in a very friendly way.” Obviously, Brady was unfamiliar with McKay, who castigated even those who gave him money, let alone those who only gave “helpful suggestions.”23

Locke did not respond directly to Brady about Schomburg’s confidence, but he would not have missed its significance. That McKay, a closeted Black nationalist, might be behind the Harlem Artists’ Guild’s declaration of independence signaled that this awakening was very different than Meyer Schapiro’s. The Harlem rebellion was a radical movement of artists who were committed to a Black Nationalist notion of art and community. Locke would have read the insertion of McKay into this challenge to the Harmon Foundation as a sign he might be as much an enemy as a friend.

As the summer of 1935 approached, Locke faced three challenges to his aesthetic leadership—Black rioters, whose protest in the streets diminished the importance of high aestheticism projects like his; a White-led radical art movement that attacked Black aesthetic nationalism as racist; and a Black-led activist insurgency that was deeply critical of the White institutional patrons he had allied with after Mason. Underlying each was a challenge to a quietist racial politics in which art was aligned with palliative measures in the Black community that did not fundamentally challenge segregation and its system of psychological degradation of Black people to maintain power and resources for Whites in America. Locke’s theory of art awakening was designed to awaken and sustain Black subjectivity without confronting—or dismantling—institutional racism, a program that was increasingly ineffectual and old-fashioned in the militant 1930s.

The American Association of Adult Education would highlight this problem. It again held its annual meeting in Virginia, without anticipating that the hotel it selected had Jim Crow policies that refused to give rooms to Black presenters and members—the very participants that the organization said it was most eager to attract to make adult education a national imperative. Cartwright sought to find “alternative” sleeping arrangements for the Negroes, rather than pull out and take the financial hit of having to hold the conference elsewhere. Plus, as an organization with national aspirations, ruling out the South as a site of the meetings would mean conceding that its adult-education agenda could not be fulfilled without desegregation, a topic the leadership studiously avoided. This time some Black members balked at Cartwright’s “arrangements,” setting up a potential confrontation with the hotel at the annual meeting.

Once again the Association turned to Locke to solve its problem. He was tired of it. Morse Cartwright was surprised. “I have just had a letter from Professor Cooper at Hampton Institute who shared your feeling with regard to the meeting. He plans to come only on Thursday and since he is to be in Washington, or Baltimore at that time anyhow, the attendance is made fairly easy.”24 But “Miss Hawes” was coming and declaring she would force integrating the Sky Lodge meeting. As usual, Black women were in the vanguard of contesting segregation’s vicious humiliations, as Locke wrote Cartwright:

I have made extensive inquiry about the policies of some of the other liberal organizations on this matter of discrimination. Such definite public announcements and comments have been made on the position of the Women’s League for Peace and Freedom, the National Conference of Social Work and the Y.W.C.A. that I am surprised to find that they have no express legislation on the matter. In each case it is an agreed policy on the part of the officers and executives of these organizations, and that they have refused to make arrangements for several years for meetings anywhere there is likely to be discrimination. Their executive officers announce such a policy to convention hotels and authorities of host cities and to delegates or agents seeking the selection of a city as a convention meeting place, and receive assurances in writing about the absence or waiving of discriminatory practices in all usual accomodations [sic] for official delegates and members of these associations.25

Locke stated that he regretted the situation had developed, but he was actually glad, for it forced the Association to take a stand on segregation at meetings, which it should have done when it first decided to get into the “Negro business.” Cartwright was forced to decide never to schedule meetings at hotels that did not explicitly state a nondiscriminatory policy and had Lyman Bryson draw something up.

As Locke wrestled with the implications of the Harlem Artists Guild rebellion and the limitations of the American Association for Adult Education as a progressive organization, a door to a more independent base of operations seemed to open. The Survey Graphic still wanted to do an article on the Harlem race riot. Rather than hire Frazier to present the riot commission report findings to the public, Kellogg continued to pressure Locke to write the article on the Harlem report. By May, the ever-resourceful Kellogg had gotten the mayor to allow Locke to read the confidential report in the mayor’s offices and to meet with the city commissioners to discuss its findings. When Kellogg supported Locke’s private recommendations to the mayor that an art center be built in Harlem, Locke agreed to do the report.

Since Locke planned to go abroad at the end of June 1936, he had little time to produce such a report. Nevertheless, he swung into action. He made several trips to New York to read the report and collect data, much of it from the commissioners who were the target of the report’s criticisms. Within record time, Locke came up with his main line of attack on the problem—to argue that the new social reality in Harlem of abject pervasive poverty and city-wide discrimination was a powder keg ready to explode and destroy Harlem—and perhaps the rest of New York—if immediate improvement of conditions was not made. Locke the harmonizer also asserted that such improvement was already occurring in large part because the La Guardia administration was moving quickly to correct the grosser hospital, education, and sanitation inadequacies of Harlem, even though he believed something more fundamental and enduring needed to happen if the soul of Harlem was to be saved. Locke was confident that his Harlem article had done what it needed to do—expose the toxic situation in Harlem, but create support for renewed progressive investment in Harlem.

Locke enthusiastically greeted his time away that summer, which took him to the Soviet Union and exposure to its program for cultural and racial minorities. The immediate rationale for going there was that the Soviet Union had refurbished its spas on the Black and Caspian Seas to cater to the traveling elite who now avoided Hitler’s Germany. Kislovodsk—Russian for sour waters—was famous for mineral springs like those at Nanheim. Ringed by gorgeous mountains, Kislovodsk was so breathtaking that Locke could only tolerate its beauty in stretches. “I have been up in the hills three times since I last wrote you—just often enough for it is really too grand for a daily experience. Of course, as in all mountain neighborhoods, you have to keep your eyes on the sky—clouds come up at short notice and pour down occasionally—but always with quick clearings and gorgeous sun-bursts afterwards.” But the most important aspect of the trip was the opportunity to see the blossoming of a new consciousness issuing forth from the Soviet regime:

The more I see of this regime, the more it impresses me. A striking example was today’s celebration in honor of the Soviet aviators who broke the world’s record. They were received in Moscow and decorated—but their first official visit was to the factory which had turned out their motor—aviators, designers and engineers went to the factory and thanked the workman who had built the plane—there is a wonderful sense of national unity and the interest in the progress of the regime is so great that long queues of people stand twice daily at the newspaper booths to get the newspapers—and then if there is a shortage, they form in small groups while some volunteer reads the paper aloud from start to finish.26

In Kislovodsk, even Asia’s nomadic peoples seemed to embrace Soviet modernism, marked by “clean hands and face,—the inevitable sign of the new influence.” Even while looking down from his pince-nez at the naive efforts of the local theater, he realized something singular was happening in the Soviet Union. “Naturally, like children, they [the Soviet players] want to show us all they have at once.” But “there is no theatre like it in the world. Each one of these minorities (Gypsies, Serbians) enjoys a state theatrical troupe on government subsidy.” The plays conveyed the stories of the people with a realism and truthfulness not imaginable in racist America, where “such things are impossible under present conditions for the Negro,” even under the Federal Theatre Project. “The Russians are the only nation treating racial and national minorities honestly and decently through and through.”27

So enthusiastic was Locke about the Soviet cultural renaissance he was witnessing that he sent Mrs. Mason, an avid anti-communist, an excerpt from the radio talk he delivered once he reached Moscow:

The Soviet Theatre is becoming a federation of many national and minority cultures, each with its place of attention and recognition. This unusual program was clearly evident in the opening festival performance of the ‘Theatre of Peoples’ Art. Here we saw excellent performances by amateurs of the folk arts of more than a score of the Russian nationalities, including minority groups that but a few years back under the old regime were not only politically oppressed and exploited, but also culturally despised and discouraged. Now with state support, their popular art is recognized and their formal art encouraged. This Theatre of People’s Art, though recently established, represents a new program of deepest significance.28

Locke witnessed in this theater a new subjectivity emerging. As an experienced skeptic, Locke knew the Soviets manufactured situations and staged spectacles of Soviet euphoria to sway visitors. And yet something in the people was indelibly different from any other oppressed minority he had observed. A disrespected people—some had always referred to the Russians as the “niggers of Europe”—had been transformed. He wanted to see that visualized in the faces of Negroes in the United States, something he glimpsed in the precolonial African faces in the MOMA exhibit, but could see nowhere else in Black America. Of course, what Locke did not see was the kind of violent revolutionary upheaval that had been necessary to make these peasant people subjects. Nowhere did Locke call for the social revolution that had upended the prior Russian society and erected a different one in its place. Rather, he wanted the revolution to be imagistic, cerebral, and symbolic. Yet he believed the Soviets had achieved something that was indelible and important to America, not only to Negroes.

Upon his return to the United States, Locke was bubbling over with enthusiasm for Russia, as recorded by the staff of Survey Graphic, who wrote Paul Kellogg, “Alain Locke was here this afternoon on the chance that he could talk to you about Russia. He wondered if you contemplate bringing out a special number on Russia. He seems convinced that the Soviet has solved the problem of economic security permanently and not merely while in the process of building.”29 Locke’s reaction resembles that of other American intellectuals who traveled to Russia in the 1930s, especially after disillusioning experiences with American reform. Not surprisingly, Kellogg ignored Locke’s suggestion to have him write an article about the Soviet “revolution.” Kellogg had had specifically Negro work for Locke to do, and from Kellogg’s perspective, Locke had already done that quite well.

Locke’s article on the riot, “Harlem: Dark Weather Vane,” had been published by the Survey Graphic in August while he was still in the Soviet Union and had been lauded generally by Kellogg and the liberal New York establishment. It had taken on added political significance when it appeared and afterward because La Guardia refused to publish the commission’s report. In essence, Locke’s article became the official report on the riot from the standpoint of the New York press, eclipsing and eliding the commission’s report authored by his colleague at Howard, sociologist E. Franklin Frazier. Frazier’s more critical report reflected the new mood among young Black social scientists of the 1930s, who not only criticized American society for its racism but also for the class and structural inequalities they believed caused the Great Depression. Not surprisingly, Kellogg was pleased with the article and wrote La Guardia shortly after it had appeared: “I should like you to know how altogether happy I am at the outcome of Dr. Locke’s appraisal of the Harlem findings. I had a cordial note from him during the summer and am sure that, from your angle, you too must have felt that my confidence in his execution of this delicate commission was not misplaced.”30

A different reaction awaited Locke when he returned to campus. Frazier asked Locke to go for a ride with him. According to Harold Lewis, a friend of theirs: “Frazier was so furious that he got Locke, I don’t know how he got him in his car, but Frazier had an old Packard what we used to call coupe, you know a two-seater, and he said later that he drove Locke all over the city telling him what he thought of him. Not only did he [Locke] get it [Frazier’s report] and published it without information, but he tended to water it down.”31 A year later, Frazier was still angry. Locke wrote Kellogg, “The social work set-up at Howard is in charge of Franklin Frazier—and there is still enough personal estrangement to make suggestions from me unwelcome in that quarter.”32

This reaction did not surprise Kellogg. When Locke had completed a draft of his article, Kellogg had circulated it among the city commissioners whom Frazier’s report had criticized to give them a chance to certify whether Locke’s article was accurate. They took full advantage of that opportunity to insist that the specific indictments of the Frazier report were no longer accurate, because the numbers had changed and most of the specific problems had been addressed in the year since the riot. But when Kellogg circulated the report to Frazier, he was livid. He wrote to the Survey Graphic and termed Locke’s article as “an attempt, first, to relieve the present administration in New York City of all responsibility for conditions in Harlem and, second, to give the impression to the public that many sections of the report will be out of date because of recent improvements. Of course, as a social scientist, you can understand why I would not be supportive of such conclusions.”33

Adding personal pain to Locke’s professional embarrassment, the city-funded Harlem Art Center he had proposed never opened. While the mayor met with Locke a few times to discuss it, in the end, he failed to act. Unfortunately, the only place the mayor found to house the center was a building controlled by the city’s Department of Education, which did not want to release it to be devoted to art activities. Then, too, the mayor may have decided that such a city-run center was no longer needed. In 1937, the WPA opened a Harlem Community Art Center, funded by federal dollars, and headed by Augusta Savage. If the federal government was funding art activities in Harlem, headed by a known art teacher and firebrand, why should the mayor open a competing center run by an outsider? The shift in cultural power from the local to the federal level, and Locke’s lack of influence in the WPA–Harlem Artists’ Guild collaboration meant, in effect, that he had no leverage. He had helped the mayor out of a difficult spot, yet had nothing, in the end, to show for it, and meanwhile he had damaged relations with a valuable colleague back at home at Howard.

Locke had been played. He had been repeatedly assured that the commission’s report would be published soon; but when the report was not published and Locke’s more optimistic article appeared, it seemed to be a cover-up. Locke had also tricked himself—lured by the prospect of a Harlem Art Center and a possible permanent position in New York, something he had wanted for years. The line that drew Frazier’s particular ire was “in some senses the report is out of date because many of the abuses mentioned in the report have been corrected.” When the draft of Locke’s article was circulated to Oswald Garrison Villard, a member of Frazier’s commission, he drew attention to it in his otherwise favorable review of the article. “Mr. Locke has done a masterful job of summing up what we have labored to communicate in much longer prose. But there is one place where he is absolutely wrong—in the matter of the abuses now having been cleared up. They have not.”34 Locke and Kellogg knew what they were doing. In all of the editing of Locke’s article that assertion remained.

Locke appears to have been taken in by the civility of his relations with both the mayor and the city administrators, who, in addition to bombarding him with statistics citing a few more Black nurses were working at Harlem Hospital than the report had claimed, wrote courteous letters that seemed to draw Locke in. Locke’s “cordial note” to Kellogg after the embarrassment of the article’s repudiation by his Howard colleague suggests how civility had to be maintained with Whites at all costs. Locke’s civility had undermined him in this situation, and his article had permanently harmed his relationship with a respected Howard colleague.

While Locke was technically correct that some of the more egregious practices of New York City administration in Harlem were changed once exposed by Frazier’s report, Harlem life was not improving. The ride in Frazier’s Packard was a wake-up call. Frazier presented a problem Locke could not navigate around without consequences. The Young Turks on Howard’s campus, the Leftist rebels in his own Social Science Division, knew that he had betrayed the larger truth of the Black situation in Harlem by pushing himself into a situation where he was not the expert. He was delegitimized in their eyes. And he could hardly be thought of more positively by the Black artists and cultural activists in Harlem, who had another piece of evidence that when a clear decision had to be made in terms of racial loyalty, Locke would side with the Whites over the Black working poor. That was not completely true; his article had made some forthright and clarion calls for action. But without any power to force La Guardia to even release the original report, let alone to commit any of his limited political capital to reforming city administration in Harlem, Locke had no compensation for having let La Guardia and his administration off the hook from having to bring real change to Harlem.

Locke did not like violence—the Harlem riot kind or the fiercely expressed harangue of Frazier in a Packard coupe. But Frazier had done something that was critical to Locke’s political self-consciousness in forcing him to listen to Black anger that would be turned on him if he did not recognize its legitimacy. Frazier’s attack on Locke had shown that he was not sufficiently identified with the advancing political consciousness of the 1930s Negro radical to represent it adequately in his public discourse. Before he got in Frazier’s Packard, Kellogg and the mayor of New York, Miss Brady and Morse Cartwright had already been taking Locke for a ride—to serve their interests; and that ride was leading to his demise as a relevant Black thinker.

As the end of 1936 approached, Locke could take heart that three of the Bronze Booklets were finally published, while the fourth, Ralph Bunche’s A World View of Race, would be out early in 1937. But Locke knew that was not enough. He had to find a way to reposition himself and his views of art’s efficacy as an enabler of the radical politics of the 1930s or become little more than an exquisite corpse—beautiful, nice to look at, with its many limbs, but dead as the Harlem Museum of Art and its cousin, the city-funded Harlem Art Center.