38

Transformation

A different Locke appeared on the stage of the pearly white Metropolitan Opera House at Broad Street in Philadelphia on October 19, 1937, to speak for the first time to a meeting of the National Negro Congress, a communist-front organization. The difference was in the location as well as the man. Locke had for years traveled thousands of miles to hear opera sung from stages like the one he was standing on in 1937, in the wonderfully ornate former Philadelphia Opera House that when built in 1908 symbolized Philadelphia’s cultural coming of age. But now, in the late years of the Great Depression, the building was rented out to any quack radical element that could pay the rental fees—an analogy to what had become of Locke himself, now that his grand vision of a Negro Renaissance of the 1920s lay in tatters. Hard times had hit the Metropolitan and Locke, for America was no longer interested in, nor able to afford, Culture with a capital C. Both the Metropolitan and Locke were struggling to reinvent themselves in times inhospitable to their original ideas, their founding missions.

Invited by John P. Davis, national secretary of the organization, to appear at the second meeting of the National Negro Congress, Locke was not on completely unfamiliar ground. The organization had been started by two of his close friends, Ralph Bunche and Arthur Fauset. But Locke would nevertheless be in unfamiliar company. A. Philip Randolph, the NNC president and head of the Sleeping Car Porters Union, was a union organizer turned intellectual who would later go on to originate the idea of the March on Washington in 1941. Davis was the firebrand organizer of the New Negro Alliance that protested discrimination in hiring in five-and-ten cent stores in Washington, D.C. The NNC also included James Ford of the Communist Party and was in the midst of a power struggle over the extent to which it would follow the line of the Communist Party USA. All of these men were activists in ways Locke usually found repugnant. And yet, here he was, answering Davis’s call to “serve as Discussion Leader of the sub-session on ‘Cultural Problems of the Negro.’ The subject of the discussion at this time will be ‘Traditions and Cultural Problems of Negro Artists.’ ”1 But Locke used his talk to do something more powerful: to transform himself into a Black radical cultural critic of the 1930s.

If Locke arrived on Friday, October 17, to the meeting, he would have heard NNC president, A. Philip Randolph, argue from the stage of the Metropolitan Opera auditorium that “while it [the NNC] does not seek, as its primary program, to organize the Negro People into trade unions and civil rights organizations, it does plan to integrate and coordinate the existing Negro organizations into one federated and collective agency so as to develop greater and more effective power. The Congress does not stress or espouse any political faith or religious creed, but seeks to formulate a minimum political, economic and social program which all Negro groups can endorse and for which they can work and fight.” “True liberation,” Randolph announced, “can be acquired and maintained only when the Negro people possess power; and power is the product and flower of organization—organization of the masses, the masses in the mills and mines, on the farms, in the factories, in churches, in fraternal organizations, in homes, colleges, women’s clubs, student groups, trade unions, tenants’ leagues, in cooperative guilds, political organizations and civil rights associations.”

Randolph was reinventing the NNC as well. From now on, he declared, the NNC would be less concerned with union organizing and promoting working-class unity between the races and more committed to Negro socialist self-determination, an argument that fit the agenda of Locke’s speech. Davis was eager to have Locke, “the unanimous choice of our committee,” to buttress the argument that the NNC was itself a kind of Popular Front organization, with a broad program of race advancement grounded in Negro culture and a broad appeal to progressive-minded Negro intellectuals of the late 1930s. Here was a perfect opportunity for Locke to launch his new cultural analysis—that the New Negro’s racial self-determination in the arts of the 1920s laid the foundation for a workers’ literature of the 1930s that would actually reach the Black masses.

When it came time for Locke to speak that Sunday, he argued that the core idea of the New Negro movement all along was to express a folk culture rooted in the Black masses; but the self-indulgent writers of the 1920s had squandered the opportunity to achieve that goal. In a nimble rationalization, Locke contended that the core of the New Negro movement was a proletarian voice that now was heard in social realist literature. He did not mention Beauty once in his speech. Rather, Locke suggested that his experience with the preceding generation gave him the perspective to counsel the coming generation not to become “dogmatic or too inflexible, because the common aim of all good art is truth through a formula and not a formula at the expense of truth.” Locke, too, was looking ahead. Perhaps if he could string together a number of presentations that inserted proletarian literature in the canon of Negro literature, he could announce himself as the critical advisor for a new generation of writers who heretofore had been enemies of the New Negro he represented in the past.2

Arthur Fauset, vice president of the NNC, may have suggested Locke to Davis to help Locke win friends and build a new sympathetic audience for his views among the young radicals who were the driving force in the NNC. Fauset was again in Locke’s good graces, after Fauset confided he was leaving the Communist Party and divorcing his wife, Crystal Bird, whom Locke hated. While the divorce did not materialize until 1944, Locke and Fauset became sufficiently reconciled for Locke to feel comfortable coming to serve as “discussion leader” at the Philadelphia meeting of an umbrella left-wing organization of Black socialists that was Fauset’s latest attempt to forge a Black radical identity as a closeted homosexual.

Locke had to distract his new audience from that he had all but erased the rebellious New Negro working-class and the radical Black socialist intellectuals of the 1920s from his version of the New Negro in The New Negro: An Interpretation. But here he was reinventing the New Negro as a Black working-class subject, whose racial self-consciousness was the inevitable forerunner of the class consciousness of the Black proletarians of the 1930s. “The contemporary generation of our artists must not overlook, however, the considerable harmony there is between the cultural racialism of the art philosophy of the 1920’s and the class proletarian art creed of today’s younger generation. In the expression of Negro folk life, they have a common denominator, as the work of Langston Hughes and Sterling Brown, who belong to both generations, clearly proves.”3 The race consciousness of the 1920s New Negro had prepared the ground for the class-conscious New Negro of the 1930s, whose essence, like the trope of the New Negro itself, was the capacity to begin again despite past tragedies.

Crediting race consciousness as part of the formation of Negro workers’ self-consciousness elicited a reaction from Loren Miller, a young Black lawyer, who lit into him during the question-and-answer period. Miller had met Locke on the ill-fated Russian film trip in 1933 and evidently had retained a dislike for him. On this occasion, Miller challenged Locke’s racial consciousness argument from a traditional Marxist point of view. He recounted how recent anthropology had determined race to be a myth and a dangerous one at that. How could Locke advocate that a new, progressive organization like the NNC wed itself to such a discredited concept or the writings of those who had created a counter-myth to Black racialism in The New Negro?4

Locke seemed ready for this attack. “Mr. Miller” was quite right that anthropology had discredited and rightly so, race as a biological concept. The New Negro had specifically repudiated such outworn ideas, except in those sections written by Albert Barnes, W. E. B. Du Bois, and James Weldon Johnson that contained the notions Miller cited. “In the editorial sections of the book such assumptions were explicitly ruled out, particularly in the sections on Negro music and art, where cultural factors were advanced as the correct explanations of characteristic traits and qualities to be found in the Negro or in Negro art.” The New Negro remained progressive and relevant in the 1930s because its “cultural racialism” advanced the right of artists to mine their ethnic and social heritage. Having already drawn a parallel between the Negro and the Irish Renaissance, Locke returned to it here with a vengeance, suggesting that no one could reasonably argue that W. B. Yeats was racist. “Dr. Locke cited the irrelevance of a question as to how much more Irish blood Yeats, Lady Gregory and Synge had than Bernard Shaw or George Moore. It was simply that Shaw and Moore had chosen to express themselves in the mainstream of traditional English culture and the adherents of the Irish Renaissance in terms of the revival of the folk-traditions and idioms of their Irish ancestors.” The Negro artist in the 1930s had the right to the same choice, “some deciding to take the one, some the other cultural platform for his art. The New Negro movement was based on the deliberate choice for emphasis of the folk values and a reconstructed racial tradition.”5 That answer handcuffed Miller, since his friend Langston Hughes was more a poet like W. B. Yeats, who chose the “emphasis of folk values” in his poems before detouring into proletarian poetry.

Adult education was Locke’s other foil against his communist critics: he was creating a literature of liberation for the masses, something acknowledged even at the National Negro Congress meeting. “The speaker [Locke] expressed appreciation for Mr. Miller’s favorable mention of the Bronze Booklet series issued by the Association in Negro Folk Education of Washington, D.C. for its effort to bring materials on Negro life and culture and problems involved in Negro life before the public at popular prices.”6 The problem was not Locke’s reluctance to endorse proletarian or agitprop art, but his continuing loyalty to racial self-consciousness as a revolutionary force in modern life.

Locke’s adult-education series gave him cover at the October meeting of the National Negro Congress, because the first batch of four Bronze Booklets had come out a month earlier. Miller referenced the Bronze Booklets as a very positive accomplishment, largely because it included Ralph Bunche’s A World View of Race. Bunche held to Miller’s view that race was little more than a wedge driven between White and Black workers. But the Bunche booklet had given Locke a lot of trouble. Bunche had taken the Boasian scientific view of race in the same direction that Miller did at the conference—that race was wholly socially constructed and should be dispensed with conceptually by all right-thinking people, especially Blacks. After Locke had received the first draft of Bunche’s manuscript, he had provided extensive editorial changes to eliminate what even Lyman Bryson called its “doctrinaire tone.” As Bryson commented in June 1936, “Evidently the young man has listened to your sage advice. … I think Bunche is badly mistaken in his principal idea … that there will be no race problem in a ‘class-less society.’ But no one who has given the subject much thought can deny that ‘race’ is a bogey raised by those who want economic advantages.”7 The series had been delayed almost six months while Bunche completed revisions that Locke insisted on.8 Nevertheless, the publication of Bunche’s booklet in the series helped Locke gain credit as a closet Marxist editor publishing the radical criticality of this younger generation of social scientists and aligning his work with theirs—since the first batch of four included two works by him.

Turning against former friends and allies was the second strategy Locke employed to shed his old skin as a leader of the Negro Renaissance and become the critic of the 1930s school of radical thinking. As early as his January 1937 Retrospective Review, “God Save Reality!” Locke began that process of separation by attacking Charles S. Johnson for A Preface to Racial Understanding: “that this book is obviously a primer for the great unenlightened does not excuse Dr. Johnson’s … obvious lapse from the advanced position of last year’s book, The Collapse of Cotton Tenancy, to the ‘coaxing school’ of moralistic gradualism and sentimental missionary appeal.”9 In the same issue, Locke praised his younger Howard University colleague, Marxist economist Abram Harris, for his critical study, The Negro as Capitalist.

More interesting was Locke’s public turn against Claude McKay, whose travelogue autobiography, A Long Way from Home, outed Locke as an intellectual old fogey precisely at the moment that he was trying to invent himself as a radical. McKay’s autobiography contained devastating thumbnail sketches of former friends like Locke, whom McKay skewered by publishing Locke’s preference for the statues of the Prussian kings in the Tiergarten that the radical German artist George Grosz had described as “the sugar-candy art of Germany.” McKay also revealed that Locke was repulsed by the drawings of George Grosz. Posing Locke against Grosz made Locke hopelessly old-fashioned in the late 1930s and revived the notion, most recently argued by Schapiro, that all racial nationalism ultimately devolved into the rabid nationalism epitomized by the Nazis. Even more tellingly, McKay described Locke as “a perfect symbol of the Aframerican rococo,” whose “metamorphosis” into “doing his utmost to appreciate the new Negro that he had uncovered” was “interesting,” but whose introduction to The New Negro was a kind of literary soufflé—all puffed up but with nothing really substantial to say.

Of course, there was some truth to McKay’s claims, which is why they hurt. Locke’s taste in German art was decidedly old-fashioned, while Locke had agonized over The New Negro introduction as failing to say what he wanted to say. But these claims were also payback for Locke’s high-handedness in changing the title of McKay’s poem, “White House,” to “White Houses,” in The New Negro and for Locke not highlighting McKay’s poetry in the Harlem issue of the Survey Graphic or The New Negro the way he did Countee Cullen’s and Langston Hughes’s. Even so, Locke thought he had done McKay some critical service by praising in print McKay’s breakthrough novel, Home to Harlem, with its revolutionary theme of cross-class, intra-racial dialogue, despite his private reservations about it. Locke had also given the perennially destitute McKay gobs of money over the years. But Locke he had not praised McKay’s later novels perhaps as much as McKay expected Locke should. As if to rub it in, McKay invited Locke to a book launch party at Sardi’s restaurant in New York in March 1937 as one of “those Mr. McKay would most like to be there.”10 It is not clear whether Locke attended the event, but he must have been hurt by the publication of A Long Way from Home. Locke always felt McKay—a bisexual confidant since the early 1920s—accepted him, but he now realized that was not true.

Locke got his chance to respond when New Challenge, a New York–based Black literary journal edited by the young communist writer Richard Wright, asked him to review McKay’s autobiography. Locke began with a philosophical question. What were the spiritual values exemplified by McKay’s memoir? Locke answered “Spiritual Truancy.” It was a devastating metaphor for a man lacking in any moral responsibility to speak for the communities that had embraced him.

Although now back on the American scene and obviously attached to Harlem by literary adoption, this undoubted talent is still spiritually unmoored, and by the testimony of this latest book, is a longer way from home than ever. A critical reader would know this without his own confession; but Mr. McKay, exposing others, succeeds by chronic habit in exposing himself and paints an apt spiritual portrait in two sentences when he says: “I had wandered far and away until I had grown into a truant by nature and undomesticated in the blood”—and later, “I am so intensely subjective as a poet, that I was not aware, at the moment of writing, that I was transformed into a medium to express a mass movement.”11

McKay had consistently encouraged others to think of him as a representative of a group—first Jamaicans, then Marxists, then New Negroes—only to repudiate them once they made any demands on him to serve the cause. “If out of a half dozen movements to which there could have been some deep loyalty of attachment, none has claimed McKay’s whole-hearted support, then surely this career is not one of cosmopolitan experiment or even innocent vagabondage, but, as I have already implied, one of chronic and perverse truancy.”12

“McKay, exposing others, succeeds by chronic habit in exposing himself” was Locke’s telling line. McKay outed others sexually but outed himself. McKay let a succession of sponsors, friends, agents, and editors think he agreed with their politics only to abandon them and their politics when they no longer suited him. “Basic and essential … [to] real spokesmanship and representative character in the ‘Negro Renaissance,’—or for that matter any movement, social or cultural [is] the acceptance of some group loyalty and the intent, as well as the ability, to express mass sentiment.” The New Negro literary movement’s purpose, Locke rationalized, was not simply to integrate individual Black writers into the Western canon of literature but to transform the writer into the voice of a community. Loyalty to a community was the litmus test of authenticity. “Even a fascinating style and the naivest egotism cannot cloak such inconsistency or condone such lack of common loyalty. One may not dictate a man’s loyalties, but must, at all events, expect him to have some.”13

A new clarity suddenly emerged in Locke’s sentences. Combat strengthened his writing. In his critique of McKay as disloyal to any community, Locke also answered criticisms of himself, most recently delivered by Frazier, that Locke’s Harlem article had been disloyal to the Black community. In attacking McKay, Locke defined a revolutionary ethics: whether racial or class-based, revolutionary art had to embed itself in a community and embody the lived experience of a people—some people—if it was to have any social meaning at all. In the process of attacking McKay, moreover, Locke defined his own calling going forward—to find a way to embed himself in the emerging new Black radical community of thinkers who, like it or not, were willing to close ranks and fight for what they believed in for a larger Black community in America. Speaking almost to himself, Locke concluded “Spiritual Truancy” with the imperative that “New Negro writers must become truer sons of the people, more loyal providers of spiritual bread and less aesthetic wastrels and truants of the streets.”

Locke accepted this as his new mission when, in “Jingo, Counter-Jingo and Us,” he took on Benjamin Stolberg’s criticism of Black aspirational and celebratory history. In the October 23 issue of the Nation, Stolberg, a well-known journalistic firebrand, had termed inspirational histories of Black success nothing more than “minority jingo.” Stolberg wrote a caustic review of Benjamin Brawley’s Negro Builders and Heroes stating that such segregated histories of Negro achievement did more harm than good by making Black people feel better about themselves rather than critiquing race and class divisions that kept Black people confined to second-class citizenship. That December, Locke answered these charges by transforming his annual retrospective review into a powerful defense of the dialectical nature of Black intellectual work. He reminded Stolberg and other commentators that, in attacking the “minority jingo,” such critics forgot to mention the original cause of such literature—“majority jingo.” An industry of popular and scholarly publication has inundated the national mind with advertisements of White accomplishment and the claim that only Whites had been successful. That discourse had to be opposed somehow. While minority jingo was a weak antidote, it did save the Negro mind from being defeated. “Thus,” Locke concluded, “we must not load all [of] the onus and (ridicule) upon the pathetic compensations of the harassed minority, though I grant it is a real disservice not to chastise both unsound and ineffective counter argument. The Negro has a right to state his side of the case (or even to have it stated for him).”14

But instead of just attacking Stolberg, Locke attacked Brawley as well for selling “Pollyanna optimism.” Black people needed critical, scientific, and sound inspiration for what serious, thoughtful, and wise marshaling of their resources could accomplish. In critiquing Brawley’s old-fashioned Black popular history, Locke laid the groundwork for his Bronze Booklet series without naming it as the antidote to racial brainwashing.

As I see it, then, there is the chaff and there is the wheat. A Negro, or anyone, who writes African history inaccurately or in distorted perspective should be scorned as a “black chauvinist,” but he can also be scotched as a tyro. A minority apologist who overcompensates or turns to quackish demagoguery should be exposed, but the front trench of controversy, which he allowed to become a dangerous salient must be re-manned with sturdier stuff and saner strategy. Or the racialist to whom group egotism is more precious than truth or who parades in the tawdry trappings of adolescent exhibitionism is, likewise, to be silenced and laughed off stage. … I merely want to point out that minority expression has its healthy as well as its unhealthy growths, and that the same garden of which jingo and counter-jingo are the vexations and even dangerous weeds has its wholesome grains and vegetables, its precious fruits and flowers.15

Here was the new Locke of the retrospective reviews—chastising radical and unsympathetic, White critics and slamming groveling Black allies whose work embarrassed him and the race. His prose had new life—an incisive, pulsing energy with sentences pulsating with rhythm and the telling metaphor. By critiquing Stolberg for his “wholesale plowing-under or burning over” of all Negro advocacy, Locke not only put him in his place, but defined himself as the interracial arbiter both Negro culture and Marxist apologetics needed—someone who could deliver “intelligent refereeing instead of ex-cathedra outlawing.” Locke shouldered the responsibility for embodying the Negro intellectual praxis of “criticizing” and “correcting” White and Black excesses rather than dismissing Negro intellectual projects.

Locke’s review also announced the third way Locke reinvented himself in the late 1930s by showing he was beginning to change his attitude toward protest literature or what he called “propaganda.” Before the review, art and propaganda were opposites in his writing; in this review, he connected them as part of a continuum. “Just as sure as revolution is successful treason and treason is unsuccessful revolution, minority jingo is good when it succeeds in offsetting either the effects or the habits of majority jingo and bad when it re-infects the minority with the majority disease. Similarly, while we are on fundamentals, good art is sound and honest propaganda, while obvious and dishonest propaganda are bad art.”16 Here, Locke finally accepted protest literature as art. What he had still to accept was that protest art was not simply a means by which the oppressed expressed pain and suffering caused by oppression, but that such art was also a tool of change. But he was moving toward a deeper, more political notion of the work that art could do.

To make that pivot, Locke weaponized his language. In 1937–1938, the military metaphor recurs throughout his writing. “The front trench of controversy which he [Brawley] allowed to become a dangerous salient must be re-manned with sturdier stuff and saner strategy.” Black intellectuals are engaged in a war with the White discourse, with themselves, with the weaker parts of their body politic, who could not “man” the flanks well enough for the main assault on White supremacy to be successful. Locke himself was “manning” up to match the level of combat inherent to left-wing politics of the decade. One way Locke ingratiated himself with the Young Turks was to take on their masculinist style in his critique.

Brawley was not the only former friend Locke attacked in a gendered critique to curry favor with the newer generation of Black (and male) thinkers. In the same issue, he took a swipe at Zora Neale Hurston’s epic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, suggesting that it was not sufficiently grounded in the folk consciousness it claimed to represent. He decried the tendency of Hurston to produce “folkloric fiction” that ignored the political critiques of the wider social context of the 1930s. Failing to recognize that Their Eyes Were Watching God was a breakthrough in making the subjectivity of Black women central to a late New Negro Renaissance novel, Locke vented in the review his frustration over Hurston’s refusal to remain “true” to the documentary folk methodology that Mrs. Mason had supported financially. But he also joined the cacophony of the new Black masculinist radicals like his Howard colleague Sterling Brown and his new acquaintance, Richard Wright, who were slamming Hurston for not dealing overtly with southern racism and Marxian notions of class struggle in her novels. To them, Hurston was part of the tradition of writing as if racism did not matter to Black people’s social consciousness.

But in critiquing Their Eyes Were Watching God, Locke was making public his misogynist project of the early days of the Negro Renaissance. Part of his queer project of becoming “the man” of Negro literary criticism in the 1920s had been to marginalize Black women’s critical agency. When he invited Hurston, a queer curious if not clearly queer Black woman rebel, into the patronage quadrangle of the late 1920s, he had found the perfect woman with whom to parry the argument that his New Negro movement was merely a mechanism for promoting the careers of young Black men. By the late 1930s, increasingly bitter because he believed Hurston and Hughes had “betrayed” him and Mason, Locke was willing to slam Hurston precisely at the moment when she created Janie, the one iconic female subject of the New Negro Renaissance. This was no accident. Part of the self-fashioning Locke did in the late 1930s was to refashion his identity as a hyper-masculine subjectivity, an aggressive male persona. Having abandoned a nurturing, read mothering, presence in his writing, Locke recast himself as the literary general who would lead the Black male assault on the citadel of White Marxism, Jewish male socialist hegemony, and anyone else—certainly Hurston—who stood in the way of his becoming relevant again.

Hurston was quick to respond. Writing to Elmer Carter, the editor of Opportunity magazine, she asserted she would “send my toenails to debate Alain Locke on the nature of the folk!” She accompanied the “toenails” challenge with a demand that the editor publish her remarks and set up a real opportunity for her to debate Locke publicly on what constituted the folk and its authentic representation in literature. Locke was glad that Carter did not take Hurston’s suggestions seriously. The episode pointed out that dissing his former friends in print could backfire in a way he might not be able to handle. Interestingly, only the women—Fauset and Hurston—who were on the receiving end of his attacks in the retrospective reviews of this period had the gumption and courage to write back and challenge his right to criticize their work.

Hurston’s counter-attack exposed that Locke was still not believable as the legitimate voice of the Black radical tradition of the 1930s. Yes, he had succeeded in his talk before the 1937 meeting of the National Negro Congress in presenting himself as a harmonizer of generational values by proposing a synthesis of the New Negro and proletarian literatures. The evolutionary metaphor was a bit weak, however, despite his persuasive argument that Black proletarian literature was the logical continuation of the New Negro radicalism of the 1920s. But he still recoiled from a complete endorsement of the new literature. Even his endorsement of Richard Wright in “Jingo, Counter-Jingo and Us” was made in the old language. He described the prose of Wright as having the salty tang of the peasant, suggesting that Locke still could only accept the working class through the language of primitivism. The year before Locke had chastised Charles S. Johnson for misreading the situation of the southern folk as that of the peasant instead of what it was: the quintessential American proletariat. But face-to-face with working-class anger, Locke fell back himself into the language of primitivism. He still struggled in 1937 and 1938 with an aesthete’s working-class bias that southern folk had to be “picturesque” for him to appreciate them.

More successfully, Locke evolved his own conception of the function of art for an oppressed people in the late 1930s. Rather than remaining wedded to the notion that art mainly functioned as an emotion-releasing catharsis for the oppressed, Locke expressed a new position in his July contribution to the Crisis, “Freedom Through Art,” written on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. Locke had been searching for a new raison d’être for art to rationalize why it still mattered in a world where the oppressed Negro faced starvation during the Great Depression and a fate worst than starvation of a lifetime of racialized class conflict that Richard Wright chronicled in his short stories. Instead of providing a distraction from the tragedy of racism in Black lives, the real function of Negro art was “self-emancipation” Locke now argued. Art no longer could be asked to take our minds away from the carcass of American democracy lining the streets of Black urban and rural communities. Now, “the proper and peculiar function of a minority literature and art” was to teach us how to liberate ourselves and Black humanity from the nightmare of American racism.

“Every oppressed group is under the necessity, both after and before its physical emancipation from the shackles of slavery,—be that slavery chattel or wage—of establishing a spiritual freedom of the mind and spirit. This cultural emancipation must needs be self-emancipation and is the proper and peculiar function of a minority literature and art. It gives unusual social significance to all forms of art expression among minorities often shading them unduly with propaganda or semi-propaganda and for whole period inflicting them also with an unusual degree of self-consciousness and self-vindication. … But for these faults and dangers we have compensation in the more vital role and more representative character of artistic self-expression among the ‘disinherited;’ they cannot afford the luxury, or shall we say the vice, of a literature and art of pure entertainment.”17

Locke’s new position parried the thrusts of such younger writers as John A. Davis, Richard Wright, Sterling Brown, and Ulysses Lee, who in a variety of essays critiqued the New Negro movement for its optimistic faith in the healing power of art. Indeed, “Freedom Through Art” was a direct answer to Richard Wright’s article “Blueprint for Negro Writing,” for Wright had argued that the Black writer should speak for the Black masses and avoid serving as an “artistic Ambassador” to Whites. When John A. Davis’s “We Win the Right to Fight for Jobs” (1938) had attacked the New Negro strategy of using art to improve race relations, Locke provided another answer to these critiques in his end-of-the-year retrospective review “The Negro: ‘New’ or Newer,” that recast his New Negro writings as a prologue to the 1930s rebellion. In “The Negro: ‘New’ or Newer,” Locke finally was able to synthesize conflicting aesthetic philosophies and values, and move from the theory of art as catharsis to a theory of art as revolutionary praxis. It still needed to be beautiful; but it had another purpose—to transform the Negro mind and transform the world. Indeed, his new position reflected his new role: he was now the critic, rather than promoter, of art and thus did apologize for weak art. Now, he was insisting that Negro artists meet the hardest tests—to be both superb artists in terms of form, and also revolutionary in terms of content. It was a tall order, but one, he argued, the Negro artist, whether literary or visual or dramatic, could no longer avoid. He could not avoid it either.

Locke’s new vision led to new speaking opportunities. He was invited in the summer of 1938 to address a retreat held by the Communist Party, in which he lobbied for a positive view of Black culture as essential to working-class unity. Indeed, the Party during the Popular Front era adopted, at least implicitly, Locke’s New Negro strategy—the social uses of Black art and culture—partly to attract “fellow travelers” like Locke, but also to combat White chauvinism in the Party. One of Locke’s points was that African American culture humanized; that was in fact what the Party was looking for as it wrestled with the White racism of some of its proletarians. In effect, the Party needed Locke’s old theory—that Negro art was a form of catharsis for the soul wounded by racism—as much as it needed his new ideology of art as a weapon of class and racial liberation. The more muscular second part of his philosophy allowed the Party and other radicals to embrace the earlier, more cathartic role that had always been his strong suit. In effect, Locke was coming around to radical aesthetics, but the radicals, especially the White radicals of the Popular Front era, were coming around to him, as well.

But the personal advance for Locke was his ability to amend his aesthetic taste and accept protest in literature, to accept a literature of the masses, and to redefine the mission of African American literature as militant mental liberation. Seeing such plays as Waiting for Lefty by Clifford Odets had helped. But no artist helped Locke move in this new direction more than Richard Wright, a fiction writer whose angry Black realism was far from the kind of “poetic realism” Locke favored. Locke had given qualified praise to some of Wright’s poetry in “Propaganda—or Poetry?” but had remained skeptical of this young writer’s work until in “Jingo, Counter-Jingo and Us” he lauded Wright’s short story, “Big Boy Leaves Home,” as “the strongest note yet struck by one of our own writers in the staccato protest realism of the rising school of ‘proletarian fiction.’ ”18 All along, Locke’s main complaint was that proletarian writing had not produced a great writer. By January 1938, Locke had begun to believe he had found one.

The fiction of Richard Wright had seduced Locke. Something in Wright’s autobiographical vignette, “Living Jim Crow,” and the short story, “Big Boy Leaves Home,” touched him. Also, Locke had interacted personally with Wright, who was the editor of the issue of New Challenge, where Locke’s review of A Long Way from Home appeared. Never really friends, there was just a whiff of sexual compatibility. But the real attraction for Locke was Wright’s powerful prose, its searing, cutting, angry attack on the whole system of silences that hid the extreme social and physical violence that underlay Jim Crow in Black lives. Reading “Big Boy Leaves Home” convinced Locke that Wright had found the way to create convincing characters whose struggle to maintain an ounce of self-respect in a crushing system was believable and moving. Wright’s short stories gave flesh and blood feeling to the larger social structure and mechanism of race and class oppression Black southerners lived under. Locke paid Wright the highest compliment he could when he suggested Wright’s relationship to the proletarian literary movement was akin to that of Jean Toomer to the Negro Renaissance: both had shown that the Black experience of America could sing in prose when narrated by a supremely gifted writer. After Locke’s review was published, Wright won the Story Magazine first prize in the WPA Writer’s Project contest for his short story, “Fire and Cloud.” Locke had external confirmation of his assessment that “Richard Wright has found a key to mass interpretation through symbolic individual instances which many have been fumbling for this long while. With this, our Negro fiction of social interpretation comes of age.”19

Then, in his 1941 retrospective review, “Of Native Sons,” Locke defended Richard Wright’s Native Son and completed the process of reinventing himself as the critic of the new literature. Against Black and White critics of the novel who claimed it was unrepresentative, Locke argued Wright’s effort was an American J’Accuse, an exposé in prose of the horrific consequences of Jim Crow segregation and placed it within the context of the work of such other realists as Erskine Caldwell and William Faulkner.

It is to Richard Wright’s everlasting credit to have hung the portrait of Bigger Thomas alongside in this gallery of stark contemporary realism. There was artistic courage and integrity of the first order in his decision to ignore both the squeamishness of the Negro minority and the deprecating bias of the prejudiced majority, full knowing that one side would like to ignore the fact that there are any Negroes like Bigger and the other like to think that Bigger is the prototype of all. Eventually, of course, this must involve the clarifying recognition that there is no one type of Negro, and that Bigger’s type has the right to its day in the literary calendar, not only for what it might add in his own right to Negro portraiture, but for what it could say about America. In fact, Wright’s portrait of Bigger Thomas says more about America than it does about the Negro, for he is the native son of the black city ghetto, with its tensions, frustrations, and resentments. The brunt of the action and the tragedy involves social forces rather than persons; it is in the first instance a Zolaesque J’Accuse pointing to the danger symptoms of a self-frustrating democracy.20

Wright’s character of Bigger Thomas was certainly not an exquisite portrait of who and what the Negro was. But the death of Black Beauty yielded a new Black sublime, in which Black literature attained significance as a purveyor of truth and justice more important in the moment than traditional notions of the beautiful.

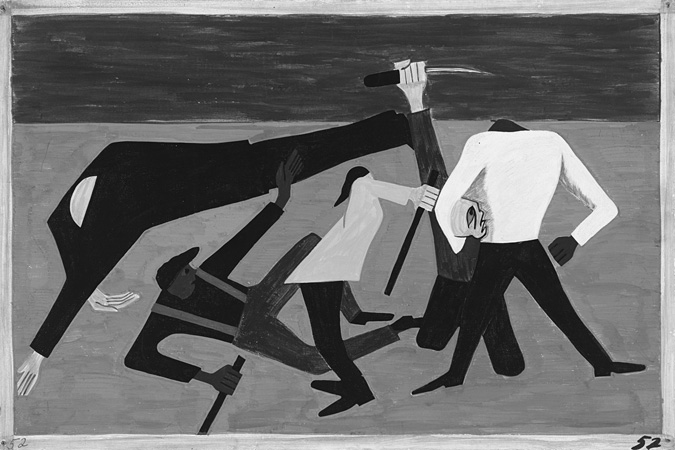

That same year he wrote so approvingly of Richard Wright’s literary breakthrough, Locke found another artist whose painterly portrait of the Black experience confronted as unflinchingly as Wright the agony and triumph of Black segregated life in America. In 1941, Jacob Lawrence, a dark-skinned product of the Great Migration, produced a sixty-panel tribute to the Great Migration that Locke had stated in 1925 was the key to the revolution he titled the New Negro. An artist birthed by that movement had matured in the Harlem of the 1930s, studied at the Harlem Art Center, and been employed by the WPA, but had escaped the handicapping formulas of either WPA American Scene celebrationism or the crippling formulas of social realism. Lawrence’s diminutive panels of scenes from the life of Black migrants exuded a strange new beauty, abstractly rendered but narratively accessible and powerful, a moving window on how life was lived and changed by the poorest of African Americans. Locke had followed Lawrence’s career for several years, had helped him get a Rosenwald grant to do the Migration Series, but nevertheless was stunned at Lawrence’s achievement in this series, for he had found a way to move beyond visual biography to translate social history into cinema-like paintings. Lawrence had distilled the African advice Locke had seen ignored by dozens of African American artists into a uniquely African American abstract expressionism that was not copied from the African but informed and enhanced by it. It confirmed what Locke had seen exemplified at the MOMA exhibit—that African abstraction could be used to portray a living proletarian movement, the Great Migration.

Wright and Lawrence had put back in the New Negro art the anger Locke had left out of the Survey Graphic—both the 1925 Harlem issue and the 1935 riot review—anger that was needed to convey the truth of the experience of Blackness in the North. On his own, Locke had not been able to see, let alone embrace, the violence of American life as lived by Black people—without help. Now, after Frazier’s challenge and Wright’s and Lawrence’s examples, Locke could see that protest was not inimical to art, but one of its highest forms. For their art revealed the ugly beauty of America that had to be embodied by Black aesthetics if freedom through art was to have any meaning at all for the oppressed.

Locke had accomplished a great deal in finding these two artists who embodied the promise announced from the stage of the Metropolitan in 1937 that a rapprochement between the race consciousness of New Negro folk movement and the criticality of the proletarian movement would yield a more authentic radical art and literature. He had crafted a new philosophy of culture that announced art was now a means and an end of freedom for the oppressed. And Locke had shed his skin as an apologist of a failed New Negro aestheticism and redefined the New Negro as a dialectical subjectivity constructed now by proletarian artists. And lest we forget, his most satisfying accomplishment was perhaps personal. Despite all his detractors, Locke had reinvented himself as an arbiter of radical Negro thinking on art and culture in the 1930s and become a force to be reckoned with in print.

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000). One of the largest race riots occurred in East St. Louis. 1940–1941. Panel 52 from The Migration Series. Tempera on gesso on composition board, 12˝ × 18˝. Gift of Mrs. David M. Levy. The Museum of Modern Art. Jacob Lawrence © 2017 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle /ARS, New York.