39

Two Trains Running

Two trains were running in Locke’s life, running parallel to his political transformation in the late 1930s. Alongside the public race man, the private Locke was running strong.

Locke had another life, a hidden life of cruising, signaling, and nonverbal communications that constituted a hidden code of communication between him and likely prospects that, more often than not, ended in success, but also disappointment. Locke was always hunting men, but always doing so with a protection system in place to hide his intentions from those not in “the life.” Robert Martin, a professor of political science at Howard University, whom Locke recruited as a young man to manage the printing and distribution operation of the Bronze Booklets produced by the Associates of Negro Folk Education, remarked about Locke’s “system.” Of course, Martin insisted, he was not one of Locke’s lovers. But he related how Locke tried to recruit him. “I was working at a local theatre in the 1930s, and we used to be required to wear these bright red uniforms, and after I had gotten to know Locke and was working distributing the Bronze Booklets, he told me that he had seen me working at that theater, and that he had made a signal to me that I would only recognize and react to if I was one of them. Of course, I had no recollection of having seen him.”1

Martin, though, was intimately involved in Locke’s affairs given that he was Locke’s only assistant handling the day-to-day operation beginning in the spring of 1937. He visited the post office box for the associates and processed the orders for books from bookstores, libraries, benevolent societies, social movement organizations, individuals, and even prisons. A trickle of requests in 1937 swelled to a flood by 1939, creating constant work answering queries, binding up books, mailing them out, and keeping track of the accounts. Meanwhile, Locke advertised, promoted, and sold the books to libraries, schools, bookstores, and anyone who would buy them. Martin’s disclaimer may have been a response to Locke’s will being published in the Washington Black newspaper. Robert Fennell, one of Locke’s students and close friends, remarked that after that, “He called me up and told me all about how he knew all of Locke’s associates, but that he wasn’t one of them, etc. I didn’t ask for that information. Really, he gave himself away with that.” Locke completely dominated Martin’s life on campus. “Martin could be seen carrying Locke’s books and bags all over campus.”2

Locke collected Black men as well as he collected the African art that bedecked his mantle at home. He mentored them and he loved them. Those, like Hercules Armstrong, came and went, often in response to their desire, usually unrealized, to become a famous writer or artist. He would gather them in, read their work, give them his honest, often searing critical opinion, and have sex with them. Sometimes Locke would try to get them jobs or place their work in publications. Sometimes that did not happen, and then they would begin to hit him up for money, usually by asking for loans. A rather awkward dance would ensue, in which Locke would know that continued access to these beautiful young men required his financial contribution to their lives, lives that were often constrained their limited talent, as well as by structural racism, chronic unemployment, and career confusion. Eventually, the sex would dry up, the touch for money would become too excruciating for the penurious Locke, and they disappeared from his life.

One of the tensions in such relationships was Locke’s criticality, especially his criticism of them if they failed. One such lover confided that Locke became upset with him when he had flunked a French exam. That was intolerable to Locke. Too many of such failures ended Locke’s interest in a young man. Of course, Locke himself had failed, disastrously at Oxford, and lied about it to keep the fiction of his uninterrupted success inviolate. Locke’s failure made his policing of other young, gay men’s failures more intense than it would have been otherwise. But its deeper root was that educational success was essential to Black Victorian identity, as Du Bois described it in “Of Our Spiritual Strivings.” After being rejected by a young White girl in a school exchange of cards and realizing he was shut out of their world, Du Bois “lived above it in a region of blue sky. … That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination time.”3 Beating the White man was essential to one’s self-respect as a Black Victorian, and Locke imposed its “discipline,” as he would probably have called it, on his young lovers, even though, existentially, as a strategy, it was failure regardless of how well one did as an academic. As Locke’s colleague in the Howard University Department of Philosophy put it, “No matter what are your credentials, a black intellectual is not accepted as an authentic man.”4 Locke insisted that young Black moderns of the 1920s and 1930s adopt his approach to the profound bitterness of this predicament, even though when those moderns saw through the tactic and realized they were condemned to be Black in a disrespectful world regardless of whether they passed their French exam or not.

Sex, however, with men added another way for Locke to keep his sky blue. They were another classroom, as he educated them on all he had learned about how to survive not only as a thoughtful Black person but also as a queer man in a world that hated queers almost as much as Negroes. They also were important in another way—they were Beauty personified, works of art themselves, their gorgeousness anchoring his love of art that featured the Black body. Something of his love for Black men explains the tenacity with which he held on to the notion that a Negro art existed from the race of the artist who rendered it. The beauty and love of these men’s bodies shaped his aesthetic taste that preferred portraits and sculpture that featured the body. That love allowed this elite White-educated misanthrope to sustain a loyalty to Black people, because beautiful Black men anchored his belief in the beauty of the Black experience. No matter what the White folks said, he knew he loved these men, and loving them was another form of resistance against the discourse of Black male inferiority America taught him and them.

But these men also served another purpose for Locke. Part of the reason Locke demanded his lovers be brilliant was that better men catalyzed his creativity. Locke’s most important intellectual breakthroughs seemed to occur at those points in his life when he desired spectacular men. At Harvard, it had been Locke’s relationship with Carl Dickerman that had helped lead him to appreciate Paul Laurence Dunbar’s achievement, when everything in his Black Victorian taste led Locke in the opposite direction. Love of Langston Hughes had turned him from a worldly aesthete into a New Negro. Smith had stimulated an important return to Locke’s earlier love affair with philosophy. Locke advanced in his intellectual life when he was intimate with really brilliant men; and he stalled and stumbled when he had to make due with less intelligent lovers. While Locke claimed his sexual raiding of young men was justified by his mentoring them into great artists, the truth was that his most important insights required catalytic men who provided alternative pathways to his typical reactions and transformed the cultural production of his life. Fundamentally, Locke was a dialogical thinker whose desired subjects shaped what he thought and did.

Bunche and brilliant young radicals had accelerated Locke’s desire to create a knowledge system that educated the masses with critical Black knowledge. And remarkably, the nonprofit publishing company Locke created to do so was thriving by 1938. Locke rented a warehouse to store the books, secured a post office box as its official mailing address, and after spending the summer of 1937 hassling authors to get the remaining books finished, had a second batch of four Bronze Booklets out by the end of the year. Sterling Brown, a poet, friend, and faculty member at Howard, did two of them. Locke had anointed Brown the best Negro folk poet in Nancy Cunard’s Negro Anthology, to Zora Neale Hurston’s chagrin, and after helping to bring him to Howard in 1929 had peppered Brown with requests to complete two Bronze Booklets until Brown finished Negro Poetry and Fiction and Negro Drama. Those two books quickly became the most popular Bronze Booklets, because they carried forward the kind of criticality that the Black reading audience hungered for and that Locke’s retrospective reviews prepared the White reading public for. When Locke sent copies of these books to Mrs. Mason, he gloated that they were essentially carrying forward his analysis of literature, which on one level was true—a Cultural Studies reading of literature as a bellwether of the mind of people was his innovation of the 1920s. But as he also admitted to her, Brown’s books were almost violent critiques of the American literary tradition, especially the southern literary tradition, for its treatment of the Negro in print, much more forceful than Locke would have dared to write. There was bound to be a reaction. “But let them,” Locke concluded, knowing full well that the brunt of the reaction would be borne by Brown, not him. The other great seller was The Economic Reconstruction and the Negro by T. Arnold Hill, the sociologist of race relations in Chicago, who had been engaged with the National Urban League in the 1930s in pressing FDR for the inclusion of Negroes in the National Industrial Recovery Act. While his booklet was not the fire-breathing tome that Du Bois had penned, it was, in fact, a solid economic critique based on experience innovating for the Negro within the New Deal.

The Associates in Negro Folk Education reached many adult Black readers, because it operated outside of segregated public education in America. It even reached White readers, who purchased, borrowed, or stole the books from bookstores, libraries, or friends and imbibed its radical critical knowledge of America in the late 1930s. How many books sold is remarkable. By the end of November 1938, Locke had sold 1,144 copies, with Brown’s Fiction selling the most at 251, and Reid’s earlier Adult Education and the Negro selling the least at 93. But another 2,542 books were sold by the end of February 1939. Hill’s Economic Reconstruction sold 382 paperbacks and 63 hardbacks in three months.

By 1940, Locke was almost out of the bestselling books by Brown and Hill, and stock of his own two booklets was nearly exhausted. He prepared to ask the Association of Adult Education for more money to reprint those for further distribution, because, given that the cost of the booklets was 50¢ each, their sale price barely met production expenses. Such success is especially remarkable given that he ran his publishing company out of a professor’s office and a warehouse with Martin, part-time. Orders flew in from the Frederick Douglass Bookstore in New York and an Arab bookstore in London, from segregated libraries all across the South, even from penitentiaries, let alone hundreds of individual buyers, who showered Locke with letters of thanks for the intellectual food these booklets brought them despite the intellectual isolation of Jim Crow America.

That Locke was able to keep this publishing company going while maintaining a full teaching schedule and authoring other books and dozens of articles and essays is astounding, but also a testament to his organizational and marketing skills. Locke created an advertising and distribution system by which Black working- and middle-class people throughout the country came into libraries to access the knowledge that other Black intellectuals wrote about but could not deliver in cheaply available texts. Locke accomplished this because the Bronze Booklets were part of an interlocking system—whenever he gave a lecture, helped organize an exhibition, and brought visitors to the university, he made sure he displayed the Bronze Booklets, advertised and distributed them through the Harmon Foundation, and made them visible at every venue he knew. Those lectures and later exhibitions made Associates in Negro Folk Education like a university extension course—since most of the books were authored by Howard professors—and made those who purchased them, literally, associates of folk education. But it was folk in Locke’s terminology, because it was not really folk knowledge but a sophisticated system of scholarly knowledge production that disseminated Black criticality far away from Howard University where most of its authors taught. Bronze Booklets announced that Black folk education had taken Negro middle-class anger at systemic racism of the knowledge industry in America and turned it into material for the reading masses.

His queerness shaped all aspects of this project, from the way that he moved secretly to garner the funding to finance the project, to his taking the title of “secretary” rather than “president” of the nonprofit organization, which allowed him to run it invisibly. Indeed the entire enterprise is largely invisible in American intellectual history and educational history, in part because he wanted it to be. It was radical knowledge in the closet. This critique of American and global White supremacy was hidden in an educational Trojan Horse—adult education—that would transform what even Whites are able to read about the Negro if they went into a library and looked up “Negro” in the finding aid. Because eventually, their thumb would come to rest on Negro Poetry and Fiction or Negro Art: Past and Present, and they would be subjected to an alternative point of view, one that argued the Negro was not crushed by the degradations of Negro-haters, but continually pushing forward, creating culture, and defining the terms of what it meant to be an American from the bottom.5 “And a queer man of color created the book you are holding in your hands,” Locke might have told them, “you just don’t know it, because I am not letting you know it.”

Yet that was not enough.

Despite Locke’s public intellectual innovations and his well-oiled engine of private promiscuity, a pain ate away at Locke’s soul in the late 1930s, as he struggled with a life without love. Of course, he had regular conquests of men and resumed contacts with those around for years. Collins George, from the 1920s, would cycle back into intimacy every so many years. There was Jimmy Daniels, the cabaret singer, who always appreciated Locke’s help, especially when he got him a job at the Los Angeles Sentinel. There were new ones, like Bili Bond a wonderfully lighthearted presence who always cheered Locke up with his joie de vivre. But Bili was a very intermittent presence, as all of them were, because Locke could not compel a lifelong love commitment from any of them.

Sometimes, Locke blamed it on Washington. Even as a relatively secure professor at a major university, with a lovely home, he felt he could not risk using either to create a platform for long-term intimacy. The first time Robert Fennell visited Locke at home he noticed that Locke was paranoid.

You know Locke’s house was the first apartment I ever visited that had a buzzer, an intercom. I was 19 years old and I came up to his house and pushed the buzzer. And he would answer, “hello?” And I would say “Fennell here,” and he would say, “Oh Fennell, come on up.” He would then ring that buzzer. But you know he would not come down to that door himself. No! He was one of the most cautious, really paranoid men that I ever met. He would change the names on his mailbox. You’d come by there and the name would be Dick Jones [Laughter] on the box; next time it would be Charles Smith. Paranoid. He never had Alain Locke on that box. And he wouldn’t open that door unless he knew who you were.6

Fennell recalled that one time Locke was furious when a friend of his brought someone to the house that Locke did not already know. Extreme cautiousness was needed to avoid life-changing scandal, but it is interesting that Fennell used the word paranoid even while being an intimate of Locke sexually. His program of survival resulted in psychological damage that imprisoned him. That prison meant that there was no chance that Locke could sustain the kind of intimacy in Washington that might lead to love.

Even more fundamentally, Locke suspected that those who slept with him did so only because of what he could do for them, not because of any love of him. He could not escape the feeling that his doorbell rang because a sexual partner wanted something from him, rather than wanting him. The story he heard from these young lovers was always the same. Their landlady was about to kick the young man out for non-payment of rent; the young man had not eaten in days and was on the verge of starvation; his clothes were in the cleaners and he needed to get them out to survive the freezing New York winter—not lies, but truths he was not responsible for that were deployed to tap the old man for money. Even when Locke helped these desperate “friends,” there was little return for his gifts, often not even thanks. And afterward, they disparaged him. Bruce Nugent contacted him in the mid-1930s after many years to ask for help getting a job on the WPA. Locke became engaged in trying to secure the job. Lacking the influence to secure such a position, Locke probably gave Nugent some money to make up for the paltry sums he received from relief. But Locke’s willingness to try and help Nugent in his desperate hours did not affect Nugent’s assessment of Locke. After Locke was dead, Nugent would tell anyone who would listen that Locke was inept in bed and unrespected by the fierce radicals like himself, Hughes, and Wallace Thurman.7

Even professional success could be interpreted as failure, as Locke would learn when he picked up the May issue of Art Front and discovered that that other train was not running so well in 1937 after all. His Howard University colleague, James Porter, had published an acid review of Locke’s Negro Art: Past and Present in that issue. “This little pamphlet,” Porter wrote, “is one of the greatest dangers to the Negro artist to arise in recent years. It contains a narrow racialist point of view. … Dr. Locke supports the defeatist philosophy of the ‘Segregationist.’ ” Porter deftly twisted Locke’s notions that the Negro artist should study African art and see himself as part of a Negro modernism in the arts into a position that confined the Negro artist to an artistic “ghetto.” The “pamphlet,” as Porter dismissively called Locke’s book, was “dangerous” because it threatened to keep the Negro artist from exercising the freedom that the “modern” situation afforded to paint, draw, and sculpt about any subject he wanted. Porter ventriloquized a critique coming out of Howard University’s Art Department begun by his mentor, James V. Herring, who, queer himself, was incensed by what he considered Locke’s traversing that department’s exclusive territory. Herring hated that Locke critiqued his idol, Henry O. Tanner, for moving to France and refusing to lead a visual arts movement among Negroes at home or abroad. Tanner was a symbol of success to academic Negro artists like Herring, whose refusal to do “racial art” made him a “pure” artist in their eyes. Such criticism was blasphemy, especially in the year of Tanner’s death. Porter delivered a blow in return.

The review’s venom was all Porter. It attacked all of Locke’s signature ideas—the notion that the Negro artist was a racial subjectivity, that Negro art existed as a dialectical formation within the world art, and that the Negro artist should be inspired by African art. Porter utilized Robert Goldwater’s argument to assert there was no connection between African art and modern art, adding his particular emphasis that there was no way that contemporary Negro artists could create art based on ancient African aesthetic principles. Interestingly, Porter also critiqued Locke’s use of Winold Reiss to illustrate The New Negro: An Interpretation, arguing that it was self-contradictory to employ an “Austrian” [sic] artist in an anthology devoted to a Negro arts movement. In Porter’s mind Negro art was only art created by Negro artists, not a way of rendering the world aesthetically that anyone could learn. Finally, Porter noted that Locke failed to mention protest art that had been engendered by the civil rights struggles of the 1930s. Here was a powerful charge, one that resonated with the likes of Romare Bearden and Augusta Savage, whose work Locke had not yet embraced. The bottom line was that Porter and his clique were aghast that having gotten the Negro artist into American art, Locke would demand they paint as racial subjects, as representatives of communities that were still outside.

Locke was quick to reply in a letter to the Art Front editor that was printed. He quoted passages from the booklet to justify his position rather than take the argument to Porter. The interesting part of the quote was its assertion that no vital breakthrough could come from Negro artists as long as their art avoided confronting the internalized prejudice, which was the price of living under White supremacy. Coincidentally, Locke had felt something quite similar to Porter’s anger thirty years earlier when “the race” seized on Locke as a “representative” and “role model” when he won the Rhodes Scholarship. But, in 1937, Porter’s cry for artistic freedom seemed to Locke a way to hide in a different kind of closet—the mask of the artist who through abstract or other nonrepresentative art, remain anonymous. Negro art could be great only if it connected to the lived experience of the Negro artist through “a very real and vital racialism. But such an adoption of the course of Negro art does not, it must always be remembered, commit us to an artistic ghetto or a restricted art province. … It binds the Negro artist only to express himself in originality and unhampered sincerity, and opens for him a relatively undeveloped field in which he has certain naturally intimate contacts and interests.”8

Nevertheless, Locke’s letter to the editor was weak. Something about Porter’s attack handcuffed Locke. Porter himself was revising his MA dissertation on Negro artists into a book and wanted to knock Locke off his perch as the reigning voice in Negro art criticism. Porter’s charge that Locke’s loyalty was not to the artists but to a racialized notion of their subjectivity problematized his reputation as their best spokesperson. There was some truth to that. For Locke, there was little that was unique about the ascendancy of Negro artists into the art world unless it was connected to the arc of the Negro subject and African aesthetic form in the Western world.

More cynically, Locke knew that most of the artists like Porter were not great artists. When Locke looked at their art as a pure aesthete, he knew that it would not have lasting significance without being in dialogue with something larger than itself. Locke proposed visual artists follow his lead and give world historical significance to their individual struggles for recognition. Even if Black people did not have the most power and were divided because of their colonial-like position in the world order, they still could behave as a cohesive group and give themselves the swagger that Europeans displayed in their art. But Locke did not dare say that in his letter to the editor.

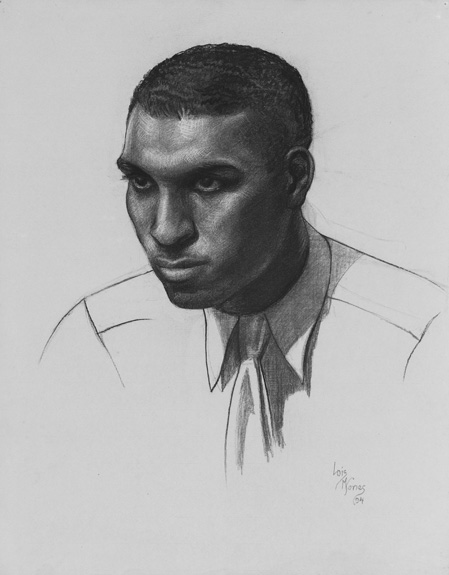

After Porter’s hostile review and Locke’s response, Howard University became a virtual battleground, as Lois Mailou Jones, an instructor in art, and John Biggers, a student at Hampton, recalled. Biggers was shocked at the level of animosity in the Art Department toward Alain Locke, who was a kind of an intellectual hero at Hampton. As Biggers put it, “At Howard, you had to choose—between following them, Porter and Herring, or Locke. I didn’t like the situation, so I got out of there.”9 Lois Jones confirmed that hostility but found a way around it to develop essentially two sides of her artistic oeuvre. “Professor Herring recruited me in 1929 because of my design work and my French Impressionist studies, not because of my Negro things.”10 But Jones recalled that when she would run into Locke on campus, he would encourage her to “do something of your own people.” She was already developing a renaissance design iconography in the early 1930s, and in 1934, had taken a step toward the kind of portraiture Locke liked in her wonderful Negro Musician. Lois Jones was assimilating the design of African masks into her portraiture, using volume and mass to give three-dimensionality and emotional depth to her portraits. She depicted the emergence of a new subjectivity in the Black community, the intense and race-proud musician whom Locke was documenting in his other pamphlet, The Negro and His Music. Clearly, Locke still had his adherents.

Negro Musician (Composer) by Löis Mailou Jones, 1934. Charcoal on paper, 23 11/16˝ × 18 5/8˝. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of the Löis Mailou Jones Pierre-Noël Trust. Photograph © 2006 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

But the review had exposed some blind spots for Locke. In 1937, he still had a problem appreciating the value of the protest art of the 1930s that moved many Negro artists to paint and sculpt. And he failed to see African art from the perspective of many working Negro artists. Despite the enthusiasm of European modernists for African art, most American Negro artists still viewed African art as “primitive” and opposed to their own definition of “modern” Negro art. Plus, African art had fallen out of favor in the 1930s among the White American art people—the WPA administrators, gallery owners, collectors, and artists whose taste ran now to “folk art”—with roughly rendered face jugs from South Carolina preferred, rather than the finely wrought sculptures from Benin. To many young Black artists on the make, African and American Negro art occupied two distinct spaces in the American art world.

Fortunately for Locke, there were a number of young artists, such as Lois Jones, Elton Fax, Bob Blackburn, Roy De Carava, and Jacob Lawrence, who saw making art and making contribution to the larger racial consciousness movement as synonymous and were not afraid of acknowledging African art as an influence in their work. But those artists were located in New York and most employed on the WPA’s Federal Art Project working on the Harlem Hospital murals and participating in the activities of the Harlem Artists Guild. Henry Bannarn had taken over from Charles Alston as the teacher on the Harlem Hospital mural project, and he shared Locke’s sensibility that art had an educational role to play in the Black community if it was not merely propagandistic. Locke, by contrast, was stuck in Washington with an increasingly hostile Howard University Art Department. Of course, his major motivation in wanting to go to New York was its more tolerant sexual atmosphere; but just as important was the other train in his life: his lifelong attempt to reconcile the career of art with the arc of the race. Most of the artists who shared that intersectional view of Negro art were located in New York. Locke was marooned at Howard.

Then, Locke learned that the Harlem Art Center that he had labored so long for with New York mayor La Guardia finally was opening its doors in 1937, but with Augusta Savage as its director. The Harlem Artists Guild working with Cahill persuaded Joseph Sheehan, superintendent of the New York City schools, to allow one of its buildings to be turned into a local art center with WPA funding. Locke had again been outmaneuvered by the introduction of federal funding into local arts education in the New Deal era. When assistant director and poet Gwendolyn Bennett, who seemed genuinely to like and respect Locke, asked him to attend the grand opening in December 1937 at 290 Lenox Avenue, with the likes of A. Philip Randolph and James Weldon Johnson giving speeches, Locke accompanied Bennett to the event. Afterward, she gushed about how much she enjoyed being there with him. It was a bittersweet moment for Locke. All of the compromises he had made and all of the alienation he had endured in trying to create a center for the arts had come to naught.

Locke became despondent as the spring of 1938 turned into summer. At first it had seemed promising, romantically. Arthur Fauset had circled back into Locke’s life once again, as Locke had written Mrs. Mason in May. Locke gushed that Fauset had “written a real Negro book—clean, clear and true—the life of Sojourner Truth. I am sending you a copy—and think you will get its spirit at a glance.” Locke also announced that he and Fauset might spend the summer together, but by July, there was no sign of Fauset in Locke’s life. As was the case with many of the men that Locke was attracted to, Fauset was bisexual and unwilling to identify himself as gay by spending a romantic summer with Locke.11

There was more depressing news. After dental surgery, Arthur Schomburg had died that June, leaving unfinished what had become their collaboration in writing the Negro history book for the Bronze Booklets. Locke would have to write it alone, but the fire was gone, along with his Puerto Rican friend. “I have the Schomburg Outlines of Negro History to finish for the last of the Bronze Booklets—since his death—about which I wrote you in early June. It is particularly difficult to write something that has to go under some one else’s name; and do justice at the same time … to him and the subject. However since we are in this sad dilemma it must be gone through with. Strange how often I get into situations like this.”12 Actually, Mason probably thought it was not strange at all. She had chastised him for years about how he had wasted his energies on being an agent of other people’s subjectivity. Fashioning opportunities for others as the publisher of a Negro studies series instead of writing and publishing those books himself had pushed him back into an old role, that of the midwife, even as pursuing it had catalyzed him to publish two books of his own. Locke mysteriously was unable to complete the volume, even though two chapters of the proposed book, obviously written by Locke, survive in his papers.

Having been energized by the founding of the Bronze Booklets in 1935, Locke had run out of creative gas by 1938. That same summer Locke probably realized he could not finish his biography of Frederick Douglass, which, at various times in the past, he had informed Mason was almost finished. Locke had hoped living with Fauset might help him complete this biography as Fauset had just completed the biography of Sojourner Truth. A midwife and sexual companionship might have helped Locke launch his own late adulthood renaissance.

Faced with another summer in steamy Washington, shut out of Berlin by Hitler, and confronting the reality that his views were out of favor on campus, Locke dreamed of a permanent move to New York, teased by the sudden death of James Weldon Johnson in a car accident and the prospect that he might replace him as a New York University teacher of Negro literature. Bryson and other White friends, such as Hugh Mearns, from his Philadelphia School of Pedagogy days, were working on that, having put his name forward. Not until the fall would Locke learn that door was blocked by another nemesis, Carl Van Vechten.

Teased by the prospect of escape to New York, Locke wrote a letter to his old Sinhalese friend, Lionel de Fonseka. In his reply, de Fonseka tried to counsel Locke in this crisis. De Fonseka, a queer aesthete who was now married and living in France, was the perfect audience for Locke’s story of woe. De Fonseka sensed the homosexual longing and frustration at the base of Locke’s desire to escape Black Washington. But de Fonseka was skeptical that a permanent move to New York was the cure.

Scrutinize the plan a little further … at New York, on your way here, you gather on the spot all the available information about all the posts available. Then here from the solitudes of Thorenc you survey the prospects of Washington + New York alike with an impartial eye, choose one or reject both—in favor of Ceylon or the Himalayas, the advantage of which will be presented to you by me personally.13

De Fonseka had some self-interest in luring Locke to France—Locke’s friend was working on a “second book” and wanted Locke to “midwife” this one as he had his earlier one. De Fonseka recommended that Locke come immediately to Europe and stay with him and his wife—traveling from New York to Cannes, bus to Thorenc, Alpes Maritimes, France. Later, he could accompany Locke back to Cannes, spend a few weeks with him there, and then Locke could return to New York on the Rex. In a sense, de Fonseka was offering the best of both worlds—a rest in a patriarchal household abroad in which the wife would minister to Locke’s emotional needs for maternal nurturing, while allowing the two men to have more romantic rewards. De Fonseka commented that he could not decide whether Locke was just tired out after having spent “two consecutive years in America,” or undergoing a real “spiritual crisis, which most men go through between 40 + 50—the men(t)opause of the males.”14 If the latter, de Fonseka believed a “spiritual adjustment” was needed rather than a “physical displacement” to New York.15

Unlike de Fonseka, Locke had no home where he could be productive and have an open sexual life. His friend had made a compromise that Locke could not make, having married a woman who not only was comfortable with de Fonseka’s sexuality but also with Locke. She too wanted Locke to come live with them, a kind of invitation to permanent expatriation that Locke would get from friends throughout his life. And yet that was also a step Locke couldn’t take. He could not give up the side of himself that was hardwired to do battle in the race wars of America even as he trekked off every summer to gay Europe.

Some more fundamental change in the calculus of Locke’s life was necessary if he was to find real peace, as de Fonseka recognized.

The sage of Thorenc … is inclined to hold to the Eastern wisdom that at 40 (in Europe + America 50) each man should cease to be a householder (translate—citizen, bread-winner, or professor … as you like) & should adopt the homeless life in the forest … leave Washington if you like but not to become a householder elsewhere. Every house in this sense that you may try to establish now will be divided against itself; so flee houses,—there is no other remedy.16

Householder was an apt term for Locke’s crisis. At fifty-three, he could not unite a house divided between the gay man of the night and the race man of the day. He could not abandon America, because he wanted others to look up to him as a leader to follow into the promised land of Negro self-fulfillment. He wanted the attention, the adulation, of Negro (and White) audiences that he went before and spoke as the representative Negro, with the authority and recognition of the race. And yet he could not live a life of personal satisfaction. Becoming another Black aesthete expatriate would cut off half of his now-mature personality. He could not perform his art—the queer Black impresario—as an expatriate, and he knew it.

Locke did not go to Europe that summer, but instead went to speak at a Harlem Communist Party summer camp in 1938. Doxey Wilkerson, a Communist Party member at the time, recalled that the Party would rent cabins for a weekend, host a variety of recreational activities, a cultural discussion, and almost inevitably a musical program in which someone sang “Negro songs.” This was the third train running in Locke’s life, hidden from view or knowledge of most who thought they knew him—his role as a closet radical. After his speech before the National Negro Congress in Philadelphia the year before, Locke had become the chosen speaker for socialists and communists, especially on the Black Left, who wanted someone to fulfill the cultural mandate of the Popular Front era to celebrate Negro culture.

Although the transcript of Locke’s remarks has not been located, most likely he spoke on the historical and cultural importance of the spirituals, and on Frederick Douglass. Douglass represented the hero Locke could not be, the hyper-masculine answer to the discourse of subservience to White male power under and after slavery, and the hero Locke could not write about sustainably. And yet there was something in Douglass’s predicament that attracted Locke, that fascinated him, a man whose courage resembled that of Locke’s father, and whose weaknesses reminded him of his father’s and his own—the egotism that Mason had accused him of, which kept him from identifying completely with Douglass. What became apparent to Locke was that Douglass was detached from the rest of the free Black population, leading Douglass to look down on other Blacks because they had not faced the challenge of the hero as he had faced it and lived to tell about it in his own words. Douglass’s triumph had been so singular—to escape slavery and to write his autobiography as a man born into slavery in his own language, and with that singularity had come arrogance that allowed for no real intimacy with other Black people who were merely free.

To have written Douglass’s biography would have required Locke to face himself and the tragedy that Black specialness and arrogance created in his personality as well. Locke could learn, however, from Douglass’s mistake of Olympian self-absorption—the refusal to bond with those who were different and less able than him, to transcend the segregation of exemplary personality to find common cause with those who could help the superlative Black individual escape the irrelevance that befell Douglass in the post–Civil War period. If Locke had written a biography that made that visible, that kind of dialogue between biography and autobiography would have been extraordinary.

Locke hated camping, the bugs, the dirt, and the uncleanliness of the food. But he went anyway—to speak about Black people’s culture and its continued relevance to a revolutionary imaginary that seemed only occasionally to include Negroes. Again, he was in vogue, mostly among younger Black communists, and Locke noticed that that summer of 1938. He would befriend people who were unlike him, heterosexuals frolicking at a communist retreat, weak-kneed White liberals who cared only to use the Negro to further their agenda, and Black radicals too young to realize the interracial revolution they imagined was not coming anytime soon.

By staying in America, by suppressing his desire to escape to Europe, and by committing to a revolutionary imaginary that barely included him, Locke did something even de Fonseka could not imagine: he sacrificed himself for the possibility of a larger good. And he did that by believing that he could be a race man and a queer man, one very much out front in racial battles while the other Locke thrived under wraps. It was a painful pragmatism. Opposed even by other queers like James Herring, attacked by haughty heterosexual queens like James Porter whose career he had advanced in the past, increasingly alone as the older generation of race men like Schomburg and James Weldon Johnson died off, Locke also could not find long-term companionship with the young blood of sexually ambivalent men like Arthur Fauset or flamboyant homosexuals like Bruce Nugent. Locke tried to turn the divisiveness of doubleness into an asset, to be a race man who loved other men, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. His goal was that he “simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both … without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face,” as Du Bois had put it in the Souls of Black Folk.17 His life proved that that resolution was possible, even if the price was a life of paranoia, nervous ticks, destabilizing habits, and a perennially broken heart.

Locke decided to believe in a positive double consciousness—that he could will himself to be both queer and race conscious in America, and succeed. Interestingly, Locke began to find new acceptance among those he had felt most alienated from—radical-minded Whites and Blacks who tolerated, perhaps even welcomed, his homosexuality. It had always been among the bohemian Whites that he had felt most comfortable. Now, under the umbrella of international Communism, he did again.

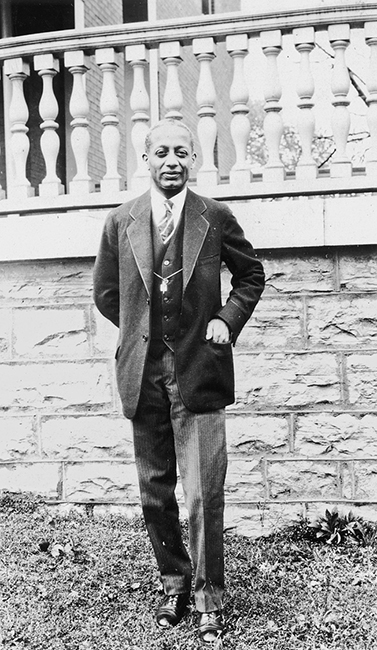

Alain Locke. Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.