41

The Invisible Locke

Locke was a chameleon who changed constantly to adapt to his context, because he feared becoming outdated, irrelevant, forgotten, a kind of living death he feared more than actual death. Because of that fear, he could never be satisfied with one avenue of success, one voice, one triumph, even those he achieved at the Baltimore Museum of Art or the American Negro Exposition. Despite legions of critics and biographers calling Locke an “aesthete,” the truth was that he was so much more—a renaissance man in the finest sense of being a man of sociology, art, philosophy, diplomacy, and the Black radical tradition—though these competencies were often invisible. But he kept feeding them, because he was afraid that art would never be enough for him to be remembered for making a difference in the lives of his fellow men and women, something he hungered to be recognized for throughout his life.

A hidden dimension of this quest for immortality occurred in January 1939, just days before his speech at the opening of the Baltimore Museum of Art exhibition. Locke answered a call from Thyra Edwards, the young Black woman internationalist who organized the American Medical Bureau in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. She was writing to ask him to speak at a meeting about race, war, and the Black role in the fight against fascism. At the Conference on the Relation of the Present Struggle in Spain to Democracy and Its Meaning to the Negro People at the Lincoln Congregational Tabernacle in Washington, in early January, Locke also volunteered to say “a strong word about the relevance of the Jewish issue” to the present struggle. Here was a Black organized radical meeting where, though again an outsider, he could greet old acquaintances like Paul Robeson and William Pickens, the latter having just returned from Spain from a fact-finding mission, and Mary Bethune, his long-time ally and friend.

In deciding to speak at the meeting, Locke was helping Edwards, an acquaintance, the kind of strong, engaged, whip-smart Black woman Locke respected. She was herself embattled with American White communists who did not think the Black contribution to the fight against fascism in Spain was that significant. Edwards had tried earlier to hold the forum on the Negro and Spanish fascism as part of the annual meeting of the League of Peace and Democracy, but the League’s leadership had refused, forcing her to put on a separate meeting to link the discussion of the persecution of Jews in Germany to the issues of Ethiopia, Spain, China, and the campaign against lynching in America. She had spent months in Spain organizing the relief effort for injured soldiers. Robeson had gone to Spain and sung, with both Franco’s fascist and Republican forces stopping fighting for a brief time to listen him. Edwards and her allies were linking their struggles for democracy in America to the democratic struggle against fascism around the world.

Locke’s reflections from the Lincoln Congregational Tabernacle provide a glimpse into what really mattered to him. After the meeting, he wrote to Mrs. Mason about listening to “Dr. Donawa, the former Howard dental man, who was dental surgeon for 18 months at the Spanish front.”1 After being forced out of his deanship by Howard president Mordecai Johnson, Dr. Arnold B. Donawa had returned to private practice and in 1938 went to tend to the injured in Spain, specializing in treating those who had had their jaws blown apart. Locke wrote touchingly about this “magnificently quiet man” who had “the courage of his convictions” to risk death in Spain because of his feeling that the fight for freedom halfway around the world meant something to Negroes. “They report over 300 American Negro volunteers in Spain before the recent evacuations,” Locke informed Mason.2 Donawa had done something Locke had been unable to do: leave the bosom of Howard to chart a heroic life on the real battlefield.

There were others. Salaria Kea became the first and only Negro nurse to work at the front in the Spanish Civil War. She had trained at Harlem Hospital and led a protest in 1933 against the discriminatory conditions for Black nurses perpetuated by Dr. Goldwater. Upon graduation, she realized she would be barred by segregation from working as a nurse among White Americans. So, she took her talents to Spain, where as a member of the American Medical Unit, Salaria tended the injured and the dying. Like Thyra Edwards, her mentor, Kea believed that what was happening in Spain was tied to what had happened to Ethiopia when Italy invaded it in 1935 and to what was continuing to happen in the United States to Negroes. African American radical activists like Edwards and Kea were key players in a leftist attempt to link the consequences of racism and fascism together in what could be called a Black internationalism.3

Their courage was one of the reasons Locke was less enamored of the strictly rhetorical anger coming out of the “Newest Negro,” as he called the radical proletarian militant writers of the late 1930s. In January, Locke also published his retrospective reviews in which he articulated a defense of the New Negro concept as still relevant to an understanding of the 1930s social protest movement in the arts and social sciences. Richard Wright critiqued the Negro Renaissance writers for being little more than ambassadors seeking the approval of Whites, and John A. Davis, who had organized boycotts of stores discriminating against Negroes in Washington, claimed the Negro Renaissance had failed because it had promised art would solve all the Negro’s problems. In “The Negro: New or Newer?” Locke countered that the New Negro not only did not promise any such thing but also that the New Negro was an evolving subjectivity that changed in dialogue with its context. Taking up their challenge, Locke revised his conception of the New Negro once again, this time as being a subject that took different identities as it worked out the right balance between the social reality of Negro life, with all of its limitations and sordidness, and the aesthetic transcendence of Negro life in its literary and other expressive forms. The New Negro had always included two voices, Locke now proclaimed, one social and critical, the other aesthetic and empathetic. While admitting the Harlem writers had abandoned representing the real in their later writings, Locke suggested that, instead of attacking one another, the Newest Negroes should stand on the shoulders of earlier New Negroes who had won the right for Negro writers to speak and act without fear. Real courage was sacrificing the glory of being the latest literary celebrity and going to Spain to fight for universal freedom.

Locke no doubt sensed, too, that part of the attack of these “bright young people” was an attack on him as the New Negro Renaissance’s homosexual leader, since the portrait drawn by Wright and Davis was a homophobic caricature of his role in the movement. Wright labeled Negro writers as “ambassadors of art” begging for recognition of the Negro’s essential humanity from Whites as weak and effeminate seekers of favors. He dismissively characterized earlier writers as lacking in courage. True masculinity and patriarchy were things American society always held just out of reach of Black men under slavery and segregation, as almost all of Richard Wright’s short stories and novels of the late 1930s and early 1940s substantiated. Part of the way John A. Davis and the activists of Washington, D.C., dealt with the pressure was to prove the masculinity of Negro men by taking it to the streets, in direct action through nonviolent demonstrations and boycotts of stores that refused to hire Black people, yet profited from their patronage.

Even with the rhetorical genius Locke displayed in “The Negro: New or Newer?” Locke realized he needed a new approach to the role of Negro epistemologies in American culture. For the criticism of these younger writers, artists, and social science intellectuals exposed the weaknesses in how Locke had formulated the argument for his cultural anthropology of the Negro people. His earlier anthropology, narrated in a series of articles in the 1920s, showed that America was in essence a Black nation from a folk and popular-culture standpoint. But younger Black Marxist intellectuals, like Ralph Bunche, Doxey Wilkerson, and Abram Harris dismissed the “Negro contributions” formula as hackneyed and unscientific. Not only did it reduce Blackness to a series of object-like gifts but it also ignored the structural nature of racism and class oppression that prevailed even after individual Whites recognized the nation’s debt to the artistic genius of Negroes. This required that Locke do more than simply expand his taste by including the struggle through protest literature, but create an updated and complex sociology of race and power on a global platform of knowledge.

If Locke was going to maintain the serious position he and other Black queer intellectuals had carved out in the 1920s—that an intervention in the discursive world of Black representation by Black artists made a difference—he was going to have to place art, literature, even Negro nationalism in a fiercer intellectual context, that of a counter-imperialist uprising challenging colonialism in theory and practice around the world. Locke was forced to recover his earlier world-systems analysis of race in his Race Contacts and Interracial Relations lectures at Howard in 1915 and 1916 in order to update his argument that culture mattered in the late 1930s. Locke would have to expand on what he did in the foreword to the catalog for the Contemporary Negro Art exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art: move away from simply emphasizing the African contribution to American culture to suggest that America was a crucible of world culture flows in which the Black remained pivotal.

That is precisely what When Peoples Meet did. The thinking behind this transformational text began in 1938 while Richard Wright and the South Side writers were composing “Blueprint for Negro Writing” to critique him and his kind as weak and irrelevant to the social realist attack on systemic racism. While they attacked him, he was preparing a discursive answer to his militant critics that in complexity and scope went beyond what they proposed. That fall of 1938, he crafted the first of several proposals to the Progressive Education Association to edit and publish a scholarly version of the Race Contacts lectures he had delivered as a young radical Black sociologist. Locke’s theory had argued in those lectures that race was the worldwide pivot of modern life in the way that Marx had treated class. That argument would be fully realized in When Peoples Meet, an anthology that offered a Black radical world systems analysis of how global racism functions as the theory and the practice of imperialism.

What made When Peoples Meet unique was the way it integrated two voices in one text. First, there was its sustained argument that while race had been dethroned as a legitimate scientific concept, it remained a powerful public discourse in the West that justified the imperialist rape of the resources of Africa and Asia. But it also documented how radicalized minorities answered—by developing practices and strategies of resistance that contained and even thwarted the brainwashing effects of the other discourse in the mind of the oppressed. Locke showed that race was not only a fig leaf for economic exploitation but also a consciousness by which communities of color built solidarity and resistance to their dehumanization at the hands of the West.

Compiled by Locke and Bernhard Stern, a radical sociologist and educator working at Columbia University, the book contained authoritative writings by experts in anthropology, sociology, and international affairs, on how difference based on color and caste operated throughout Africa, British India, and East Asia. Not only about Black Americans, it showed how race kept Africans, Asians, Latin Americans, and others under the thumb of Western nations. For example, Locke and Stern reprinted an excerpt from Half-Caste (1937) by Cedric Dover, an example of the Newest Negro consciousness except that he was Indian. Dover’s entry stated: “The dominance of color prejudice in the social scene must be attributed primarily to the unmoral economic relations between technically advanced and backward groups, and not to ethnic differences which are deliberately used to rationalize aggression.”4 Dover argued that the English were genetically as related to the population of Northern India as to the Welsh, yet the racial antagonism of the English toward the Indian far outstripped that manifested against the Welsh.

Here was the new criticality—using anthropological analysis to demystify racist explanations for imperialist behavior, yet focused clearly on the persistence of those myths and the exploitations they justify. The key to understanding race practice was to see its economic origins, as Locke had argued in Race Contacts and as Dover pointed out in linking anti-Indian feeling in England to Indian boycotts against British goods. This 1930s generation of new radical thinkers understood that the oppressed had as their only defense a counter-hatred for those who hated them.

When Peoples Meet brought together a new generation of African American, Asian, and Hispanic intellectuals who constituted a new renaissance. By emphasizing their scientific, sociological, and political revelations, Locke demonstrated an anti-colonialist awakening around the globe. When Peoples Meet revises the notion of what the renaissance really is—the awakening of humanity, including the Black, Brown, and Asian people excluded from the European renaissance, to their collective humanity through critique of the imperialist project.

How did Locke get such a radical book published in the early 1940s by an organization like the Progressive Education Association? It appears that Locke first began recruiting the Progressive Education Association (PEA) after 1932, when this rather sleepy progressive education advocacy group shifted its agenda toward seeing teachers as change agents to be armed with the latest “scientific” information about social conflict. Locke first proposed When Peoples Meet as an “intercultural” sourcebook that would help educators understand what happened when different cultures “met” and how to manage the conflict that almost inevitably resulted. This less volatile discourse of cultural pluralism allowed the book to be seen and promoted as a manual of how race conflicts could be managed rationally without any fundamental change in how the West behaved. But buried within its later sections was clearly documented evidence that, without a radical economic and political change, Western nations were not going to have an easy time continuing the imperialist mindset of the past. Locke’s radicalism had been—and to some extent remained—invisible in a text that otherwise seemed like a primer for cosmopolitanism.

Of course, to produce this text, Locke wanted to get paid, and the PEA had very little money. But it did have a close and trusted relationship with the General Education Board (GEB), which had been endowed by John D. Rockefeller. As he had earlier with Carnegie and the American Association for Adult Education, Locke realized early that he would have to triangulate the PEA and the GEB and another “expert” if he wanted to get When Peoples Meet funded.

But Locke was not the only dog in the hunt. Charles Johnson, at Fisk, was also seeking funds for his path-breaking but relatively conservative studies of southern segregation. The NAACP was also seeking funds from the GEB; but it was refused, because board members thought it had harmed more than helped the situation of the Negro in the South. Carter G. Woodson was also in the chase for GEB funding, but was turned down because he was “too independent” and his public-education projects, such as Negro history week publications, were not perceived as in line with the board’s agenda to fund “scholarly” projects. Locke succeeded where Woodson failed because he had invested years in building up relationships with the key players in the Progressive Education Association, tailored his request to the mindset of those players, and reflected the higher-education orientation of the General Education Board to publish “sourcebooks” of scholarship for teachers. By pitching his book as a resource on global intercultural problems for teachers, Locke persuaded the PEA to bring his knowledge of global thinking and practices about race to the White educators’ audience. Here was a clue to why Locke kept his radical voice largely invisible to his public persona. Instead of developing a new theory of how race and class reinforced one another in Western imperialism in the pages of Opportunity and the Crisis, or publishing a scholarly tome on the subject, Locke chose a relatively obscure venue to fund his trenchant contribution to the Black radical tradition and, because of his invisibility as a radical, and a Black nationalist, he could also get paid.

Even so, the going was slow until 1938, when Locke felt he had built enough trust with the PEA leadership to propose a book on intercultural education. His idea immediately elicited objections from Henry Lasswell, a Yale University political scientist and social science theorist, who argued that such a book on how to advance intercultural understanding between diverse peoples would have to start as a research project. Not wanting to undertake that kind of academic heavy lifting, Locke offered to put together a sourcebook of writings already penned by authorities in anthropology, sociology, and political science on the theory and practice of race around the world aimed at teachers at the high school and college level. He would write the introduction and the substantial headnotes to each section of readings. Because he lacked the time and expertise to read such a voluminous literature, he needed a partner to select the individual essays to be included in the sourcebook. George Counts, who had set the PEA in its new direction, had been a professor at Columbia University, which led to the PEA’s sea change, so it was socially competent for Locke to get somebody from there to serve as his co-editor and thereby legitimate the project. That Locke had tilted toward the radical is revealed by his choice of Bernhard Stern. There were many social scientists he could have chosen, but he selected someone not only deeply involved in the Columbia school of progressive thinking but also a fierce critic of anti-communists.

Locke’s proposed that he and Stern be paid to take sabbaticals from their regular teaching duties to write the book, a rare practice in the 1930s. This would serve several purposes at once: buy Locke time away from teaching to work on all of his projects, including this one; leave Washington and Howard University for Columbia, where his entrée in a community of White radical scholars might help advance his career; and access a small, but well-established audience of upper-middle-class White teachers at the secondary and college level as a new market for his ideas. Locke submitted the proposal in November 1938 for $5,000, part of which would be in the form of payment for Locke and Stern to run summer workshops based on the readings for teachers and the rest to replace part of their normal teaching salary. Barely a month after Locke attended the conference on the Negro’s role in the fight against fascism in Europe, the GEB would fund the intellectual explanation of how fascism was part of a larger global struggle against minorities around the world.5

During the summer of 1939, Locke and Stern received $500 each to conduct the summer workshops on race at Sarah Lawrence College, to be followed by another set of such workshops at other universities, including the University of Chicago, the next summer. These workshops allowed the PEA to show that the funding was being used to immediately educate teachers in this new global area of race. But the workshops were also part of a complex process of review, response, and revision, as the PEA required Locke to submit drafts of the book to various stakeholders in the field, including Ruth Benedict, the heir apparent to Franz Boas, and anthropologist Melville Herskovits. The constant work of revising the table of contents and consulting with experts slowed the process of assembling the manuscript.

A letter to Miss Brady reveals that all the while Locke was compiling the first draft of When Peoples Meet, he was attending and managing conferences, as well as searching for materials for The Negro in Art. In essence, he was working on both book projects, but because he was being paid by the GEB, The Negro in Art was on the backburner. “I was out of town,” he notified Brady, “at Tuskegee for three days—our second annual conference on Adult Education among Negroes,” a seemingly biannual obligation to keep up contacts with those he represented in publishing the Bronze Booklets. From there he jumped over to Georgia and spent “a day and a half at Atlanta, getting final materials from there for the portfolio,” presumably plates of the Hale Woodruff Amistad panels that would be in the spectacular color insert of The Negro in Art. He lamented, “It should have been done before, but I just turned in with Stern a 1260 page manuscript to Progressive Education Assoc[iation] (the General Education Board project.)”6

Shortly after Locke turned in the first draft of When Peoples Meet to the PEA, he ducked into the Hotel Annapolis on L Street in Washington, D.C., on March 2, 1940, for the Fourth Annual Conference of the American Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born, a communist front organization that nevertheless had a long progressive and inclusive history. Founded in 1933 by Roger Baldwin of the ACLU to focus on defending immigrants seeking refuge in the United States after fleeing European fascism, the group helped the foreign-born to become citizens, fought anti-immigrant legislation, and raised awareness about immigrant discrimination in the United States. While President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a welcoming telegram to the conference, the major backer of the organization was the Communist Party USA, especially its International Labor Defense Fund, the CP legal arm that had defended the Scottsboro Boys and now shielded immigrants from deportation who were part of radical unions or sympathetic to the Soviet Union.

Locke was not there on his own initiative, but as a representative of the League of American Writers, another communist front organization, which had asked Locke to write a report on the proceedings and get himself elected to its board of directors. There is no other evidence that Locke was even a member of the League of American Writers, so invisible was his relationship to them. His report reveals that the meeting was run almost entirely by Black intellectuals from Howard University. Max Yergen, the Black radical activist and president of the National Negro Congress was supposed to preside but did not attend. William Hastie, the dean of the Howard University Law School, substituted for him. Charles Houston, the subsequent dean of Howard’s Law School, delivered a report urging the education of all American citizens about the value of tolerance toward the foreign born. An organization founded to defend the civil rights of the “foreign born” was being steered by leftist Black intellectuals. That they had such a prominent role may explain why Locke was sent on this mission, but also why he was interested in going—to hear radical-thinking Black intellectuals direct an integrated radical organization that linked the issues of refugees fleeing fascism to Negroes fighting racism in America.7

Refugees from fascism, ironically, were seeking solace in the belly of American racism. That last fact became clear when the assembled members voted to send a letter of protest to the District of Columbia council, the House of Representatives, and the US Senate protesting that the hotel management had refused to allow the head of the Caribbean labor union attending the conference to ride in the hotel elevator. As Locke noted in his report, a “wit” stated, “Confucius say it is not news that a Negro is discriminated in a District of Columbia hotel, but it is ‘news’ when a white organization sends a letter of protest about it to the newspapers and US government agencies.” That wit was probably none other than Alain Locke.8

This meeting shows that Black intellectuals were using communist front organizations to advance a progressive agenda that made Negro civil rights an internationalist issue on the eve of US entry into World War II. They were suggesting that the foreign born, whether communist or not, had to be linked to the cause to eradicate racism in America if they wanted the support of Black thinkers to help eradicate xenophobia and anti-immigrant laws in America.

So, what at first appears as an oddity for Locke is actually the opposite—the natural progression in his political education, as his pursuit of approval from and allegiance with the Newest Negroes of the 1930s forced him toward a post-essentialist notion of the role Negro leadership could play in a global war against fascism. Despite his occasional anti-Semitic remarks to Mason, who engendered and expected them from her Blacks, Locke was pro-Jewish, believing, as many of his friends testified, that Black people needed to be more like Jews in many ways, but especially in their international solidarity. He was comfortable supporting their domestic struggle to find acceptance in America, and representing the League of American Writers, because he was representing writers and defending their human right to write and have their writings about their experience of fascism read. Fascism brought a man who avoided radicalism into the lines of communists and other radicals who would have been ignored in less threatening times.

Locke’s biracialism in 1940 was consistent with a move toward a post-essentialist advocacy of racial enlightenment. It was not that Locke was an essentialist—his notion of Negro identity was always based on the notion that to be Negro, especially a New Negro, was derived from a dialogue with Whiteness and Africa—as The Negro in Art would soon show. By including Asian and Latin American discourses, When Peoples Meet liberated his critique from having to bear a “Black only” burden. Attending the meeting of the American Committee on the Foreign Born added Eastern Europeans and European Jews to a mix that was now transracial, transnational, and anti-fascist.

Despite this new affinity with radicals, Locke’s aesthetic voice remained his primary voice in 1940. When he attended the meeting of the American Foreign Born, Locke was putting the finishing touches on the premier concert stage performance of And They Lynched Him on a Tree, a choral work by William Grant Still accompanying a poem by Katherine Graham Chapin, Godmother’s niece, also known as Mrs. Biddle, that Locke had midwifed.9 Back in 1939, Locke had attended a musical performance of Lament by Katherine Graham Chapin, who had hit upon the idea of putting her poetry to music. Locke, always the critic, expressed to Mason after the performance that he was disappointed in the music. Perhaps Biddle could rework Lament into a more powerful statement on a topic dear to Mason’s heart, the scourge of lynching in America. Chapin had what Locke was looking for in a poet of protest—poise, restraint, and irony when taking on an emotionally charged subject—plus the courage to attack it as a White woman. Locke also had a recommendation as to who should set the poem to music—William Grant Still, his favorite classically trained New Negro composer. When Locke proposed it to Mason, she embraced the idea and Chapin jumped at the chance for a unique collaboration. Indeed, Chapin was so enthusiastic she not only dashed off the new poem in a month but also flew out to Los Angeles to meet the reclusive Still, to ensure they would be in harmony in creating the new work of art.

Unlike Locke’s earlier collaborations sponsored by Mason, there is no evidence that Mason interfered this time. She asked Locke to send her Still’s name in writing, as that would facilitate her sending him telepathic messages of support “wirelessly,” while he struggled in January with the complex composition. Key to Chapin’s poem was that it contained two voices—represented by Still by two choruses, one White, one Black, that sing contesting responses to the lynching. Chapin’s brilliant insight was that lynching in essence reflected two different views of America, one that endorsed the brutal and public murder of Black people outside the law as just, and the other appalled and enraged by the White mobs’ desecration of Black bodies. This tension was embodied in the choral composition.

At Locke’s and Mason’s urging, Still finished the composition in May 1940 and was contacted immediately by Artur Rodzinski to perform the work on a program in Lewisohn Stadium, Philadelphia. Locke’s and Mason’s attempts to secure Marian Anderson failed, despite numerous attempts by Locke; but an able substitute, Luis Burge, agreed to sing the mother’s lament. Also important, Chapin insisted on a Negro chorus to sing in the maiden performance of the piece.10

All went well until the conductor read the poem carefully and panicked thinking that the final two lines

Talk of justice and take your stand,

But a long dark shadow will fall across your land

would cause a strong negative reaction to the performance and those associated with it. Still and Chapin conferred, and agreed to make a change, but that introduced musical challenges for Still, since the music was scored exactly to match the words. Locke weighed in because he knew that changing the words and the music also threatened the takeaway from the performance by the audience, since the mood of righteous indignation had to be balanced by a sense of pity, irony, and compassion achieved in the original ending. Three different versions were still in play by the evening of the performance. While the program printed the less-inflammatory version, the chorus sang the original lines on June 25, 1940, to thirteen thousand in attendance, a packed house largely because Paul Robeson was also performing Ballad for Americans on the same night.

During the negotiations with the conductor, Locke, Chapin, and Still realized that Rodzinski was concerned about the possibility that the critique of the United States as a land that would pay a price for lynching might elicit a backlash from the government and affect the status of his sister, who was trapped in Poland attempting to immigrate to the United States. His objection to those lines was muted after Chapin got her husband, Francis Biddle, United States Solicitor General, to use his influence to secure a visa for the conductor’s sister to come to the United States on the first boat leaving. This issue also suggests another possible reason Locke was at the meeting of the American Foreign Born in March. Increasingly, the future of African American aesthetics was bound up with the plight of the foreign born.11

Truth could speak the language of beauty, as Locke put it when he came to write “Ballad for Democracy” about the performance And They Lynched Him on a Tree “under the baton of Artur Rodzinski.”12 The evening was an enduring contribution to serious American music, according to Locke, because it was art—even as it made a political statement to the conscience of America. Unlike so many other reactions to Scottsboro and the continuing horror of lynching in America, its art was perfectly synchronized with its message. It was tough to express the emotions engendered by lynching musically without becoming shrill, but Still had risen to the challenge. That two choruses, one Black, one White, sang about lynching on the same stage in Philadelphia, was a metaphor for the two voices of America, being put into conversation on this brutal subject in an unprecedented way. The resolution of the musical composition—the two choruses had become one at the end—was a prophetic metaphor of where the nation would arrive, eventually, Locke, Still, and Chapin hoped, on the subject of lynching: one united voice for democracy. That a major classical music performance could be done based on the experience of lynching was a breakthrough because it was aimed at that ruling political class in America during debate in Congress over an anti-lynching bill.

“Ballad for Democracy” showed that Locke’s aesthetic voice commingled with his radical internationalist voice when he wrote about this rarefied concert in 1940. Forced, perhaps, to justify why a poem on lynching was important as art, Locke quickly moved from saying that Chapin’s poem, unlike so many others, made this American tragedy into true art, to making a very powerful statement of the international importance of lynching and America’s star-crossed democracy now that the world was at war. Like the double chorus of And They Lynched Him on a Tree, Locke’s two voices as a critic were united in this essay, as an intellectual whose social criticality and international political consciousness were in sync with his aesthetic judgment. Locke had found his true voice.

What really distinguished this new vision of democracy was the Black world systems perspective that Locke imported into an article on a choral classical music concert from When Peoples Meet. When discussing the violations of American civil rights under American democracy, he declared, “democracy is sick,” and the cure, he said, is not found only domestically.

Let us glance at a stock list of our negative social symptoms. Britain has, here in the Caribbean, in Africa and India, indeed the world over, the critical problems of her colonial holdings. The United States has her perennial holdover problem of the Negro, her oriental exclusion dilemma, her Indian and other minority problems. France not only has her segment of the problem of empire but the ironic paradox of her yet unliberated colonial children safeguarding a democratic patrimony otherwise lost. Holland has her colonial problems, too, which in the chastisement of recent loss, she seems to be facing with clarified vision.

India, in turn has grievous internal problems of caste and her Hindu-Muslim mistrusts; Central Europe, the hard puzzle of reconciling her fanatical rationalism with the welfare of her minorities. Palestine has known its sad feud of Jew and Arab; while many of the American Republics to the south of us, have the problems of their Indian peasantry, their labor serfdom and the need for their progressive incorporation in the mainstream of the national life. Last but not least, in almost all our countries there looms up, to varying degrees, the disturbing undemocratic phenomenon of anti-Semitism.

Worst irony of all, observe the same undemocratic behaviour, venting itself in a Southern lynching or a mid-western race riot, boomeranged back at American democracy in mocking and insidious Japanese propaganda.13

Taken directly from When Peoples Meet was the notion that racism was not color prejudice, but the use of difference to create hierarchies of privilege and power that, in the face of world war, threatened the very existence of democracy. “These are no longer domestic affairs,” he concluded.

Mason wrote Locke after receiving a copy of “Ballad for Democracy” that she loved the article, and in that missive laid a deeper message about the fusion of his double voice. The achievement of a more powerful single voice was the fulfillment of her vision. As a White woman in love with power, she had always wanted him to deal with the Black situation as she imagined she would deal with it, with the kind of certitude of authority, criticality, and power that he had now displayed in “Ballad for Democracy.” The review marked a powerful resolution of their relationship. She had worked her criticality on Locke to fulfill her own needs for dominance, but also toward a higher end, at least in her mind, and his—to awaken a similarly powerful criticality to make him a stronger voice for liberation, which he now was.

On September 13, 1940, Locke wrote Mason thanking her for the letter of praise that reached him on his birthday. Receiving it “now is like a new birth. And indeed, Godmother, I hope it will be a new birth. Late as it is, with this crisis in the world, I hope to be of some real service to my people, and to the principles involved. To have been led all these years, so patiently by you to the point where I can hear, see and speak truth is a great thing.”14 The real truth was that that resolution had occurred largely because of work he had done outside the orbit of her influence. It was actually his moving away from her, his odyssey into the hotbed radicalism of the 1930s that had catalyzed a renaissance of earlier Race Contacts criticality in him and helped bring it forward into conversation with the enduring aesthete.

And They Lynched Him on a Tree also marked the year when Locke was at his collaborative best. Not only was he putting himself in dialogue with people he would have avoided before but also he was putting people like Chapin and Still in collaboration with one another, people who would never have met, let alone worked together, to create a unique racial collaboration on lynching, without him. Locke was a stronger and more effective harmonizer of divergent values, communities, and people in 1940 than he had been in the 1920s when such efforts often had resulted in disappointment and hurt feelings.

That year Locke also helped repair a breech between the gifted but star-crossed artist, Charles Sebree, and Countee Cullen. Early in 1940, the destitute Sebree contacted Locke for help. Sebree was well known in Chicago Black arts circles as a brilliant artist whose odd, curiously enigmatic drawings almost always sold where other, more realist renderings by the Chicago group of visual artists did not. Sebree’s paintings did not read as Negro, but fused Arab, Middle Eastern, and Byzantium influences into a unique aesthetic, with faces large, distorted, heavily outlined, and overly expressive, especially in his treatment of eyes, which seemed like spiritual orbs in his compositions.

By March 1940, Sebree had alienated friends and supporters by being ingratiating and vulnerable sometimes and vicious and vindictive at others. He also was a braggart and unrepentant liar, who consistently invented stories about himself to fight off the psychological costs of going without food. Locke weighed in on this particular feature of his personality when he wrote to Sebree in April and chastised him for spreading “rumors of prosperity.” Locke opined, “this ‘make-believe’ is one of the roots of your trouble, not that we should wear our hearts on our sleeves for daws [sic] to peek at but at the same time, one should I think not indulge in this inflation game, if we expect to be true artists, or do the Negro cause any good.”15 This letter suggests that Locke used racial discourse to instill a higher sense of responsibility in the artists and encourage them to view their art and themselves as serious enough to avoid triviality. Sebree was hitting Locke up to purchase some of his artwork, but Locke wanted to focus Sebree’s attention on the work to be done, especially his outstanding commitment to illustrate Countee Cullen’s book, an offer that seems to have been rescinded by Cullen because of Sebree’s unstable behavior. Locke recommended that Sebree allow him to try and repair the breach and get Sebree to New York to work on the book with Cullen. As always, Locke accompanied his offer of help with a dose of criticism: “Surely, you have in mind getting out of your rut of Dantesque adolescents, for much as I and other sophisticates like them, that isn’t painting up to today’s outlook, and represents an over-worked vein in your work, in technique and theme.”16

Sebree acknowledged Locke’s criticism. “In so many words Chicago has really defeated me and my purpose. If I can go back to New York and work[,] Co[u]ntee Cullen will make arrangements for all of my meals and all that I lack is a small room and materials enough to prepare for a show of next late fall.” He felt he had “curbed a personality that has been in my way” and offered that, despite his having disappointed many of his friends, some people still had faith in his ability to “carry on from where I really started in new directions or approaches. As for functional form of the mind the image will follow the free bent of desire[; it] wont be so vigorously repressed here in the east. Mr. Locke if I can free myself from mental misery, much watching and at times much crime.”17 The mangled reference to “free bent of desire” seemed to reference his sexual orientation as a queer Black man and his sense that some of his art as an “out” homosexual was considered too offensive for the Chicago Negro art scene. He hoped, in other words, that if he could get to New York, and especially Harlem, he could “free” himself from the tendency to respond to repression by acting out, stealing, and embarrassing himself and his friends. Locke was buoyed by the sense that Sebree was ready to mend his ways, the first sign of which was that he accepted what Locke had to say to him.

Why was Locke so willing to help Sebree? “He really is a genius,” Locke wrote to Mary Beattie Brady, whom he was trying to get interested in Sebree, “pitifully naïve and helpless on one side, and willful and cunning on the other; a real double personality. I think he knows it and plays it. However, he deserves help, but I am all the more impressed as to the wisdom of my initial advice, to help him with materials and living facilities rather than cash. He probably will never learn how to dole out cash.” Unlike Sebree, Locke was not naive: he was calculating to a fault and always disciplined, a sign to him of being a cultured person. For example, Locke had a reputation for instructing young people how to sip rather than guzzle wine at his apartment, while he also instructed them on how to get control of their lives. Sebree was the ideal child for Locke to mentor, since he took pride in bringing order to people who were personally out of order. And it suggests the balance that working with artists must have brought to Locke psychologically. Their craziness provided a way out of his obsessive desire for control that stifled his own creativity.

Realizing that his future depended on Locke’s help, Sebree gave him complete control over his affairs, agreed not to talk to his friends about the plans before or after arriving in New York, and allowed Locke to act on his behalf in patching up the relationship with Cullen. In a sense, Locke’s demands in exchange for helping Sebree were remarkably similar to those Mason imposed on Langston Hughes. Locke was mirroring her as he mentored Sebree. “Shall see Countee Thursday or Friday in New York. If he and I can arrive at some understanding your problem may be solved. I urge you not to write him in the meantime, however, and hope you will trust my judgment on this.”18 Here was another motivation for mentoring Sebree—the younger man’s very helplessness gave Locke the kind of power he liked to wield in relationships. “But you must let me handle it in my own way. I shall write you immediately afterward, and hold your fingers crossed until then. Of course, if you want to write me in greater detail re your contacts with Countee, all the better, but that is left to your judgment. And now good cheer and better spirits. Tell me in detail your present resources, down to the last dime.”19 Once again, Locke the mother was in charge.

Evidently, the meeting was successful. Key to that success was that Locke provided the money for Sebree to find a room and pay for his living expenses while he worked with Cullen to finish the illustrations for The Lost Zoo. Toward the end of April, Cullen could write to Locke, “Sebree arrived, located a place, seems happy and full of enthusiasm and purpose. I think we are doing the right thing.”20 Not only was Sebree happy, but he had almost completed drawings for Cullen’s book on cats. With Locke paying for Sebree and Sebree applying himself to the project, “Countee has been very helpful and fed me so well.”21 The results were worth it, at least to Cullen. By the end of 1940, his book, The Lost Zoo, appeared with Sebree’s unique drawings of the animals that had not been allowed onto Noah’s Ark.22

The book’s title could be an epitaph of Locke’s failed collaborations with writers and lovers of the 1920s; but this time, the outcomes were different. Locke had broken with Cullen over his marriage to Yolanda Du Bois and had had a rather critical and distanced relationship to him since the 1920s. Locke was able to keep himself out of the minutiae of The Lost Zoo project—again, much like Mason—and allow the project to move forward on its own once its internal obstacles had been removed. Locke was wiser now about what he could and should do in collaborative work and what he should leave to the principals to work out, so that art would emerge from his ability to put people in positive synergy with one another to produce art.

Part of the reason the aesthetic voice, unalloyed with radical sociology, remained dominant in Locke’s life was that it was more often tied to sex. At one time or another, most likely Cullen and Sebree were lovers. That seems unlikely with Stern and the When Peoples Meet project. But the difference in attraction of these disparate projects went deeper than that. In America, the aesthetic voice of the Negro was always more rewarded than the Black world systems voice. That Locke had been able to fuse these voices temporarily in “Ballad for Democracy” that August did not mean they were no longer separately rewarded in the marketplace. As George Bernard Shaw quipped to Paul Robeson after he complained of reactions to his increasingly political commentary at his concerts, “Just sing ‘Ol Man River.’ ” Shortly after Locke and Stern completed another set of summer workshops for the Progressive Education Association to whet the appetite of teachers, they learned that the publisher the Association had selected had rejected it. PEA president Frederick Redefer suggested one possible explanation for the publisher rejecting the project was that in the midst of the Depression, the book did not have as defined an audience as Stern’s other publications had had. It was also possible that the work upon close reading raised some political concerns. Just as Rodzinski had worried that too critical a view of America in And They Lynched Him might result in a backlash, so too a social policy publisher might think the text that put American racism under the same umbrella as British and French imperialism might be too controversial.

The benefit, therefore, of having more than one voice meant that Locke was never stuck when a particular project stalled because it did not find the kind of support it deserved. The downside was that the critical edge the Black radical voice could bring to his aesthetic endeavors was muted and the aesthetic voicing of his sociological insights remained silent. He had to speak to separate communities of listeners in different voices to remain successful. That meant that the composite, complex, sociologist behind his aesthetic judgment—think of the sociology behind “Harlem” in the 1925 Survey Graphic—remained largely invisible.

To Locke, of course, the benefits outweighed the negatives. The separation, if not segregation of his aesthetic and sociological projects, meant that they had autonomous streams of support; and when one dried up, usually, another was flowing again. For example, when Keppel’s “experts” stalled The Negro in Art in 1938, Locke adeptly shifted to proposals for the intercultural sourcebook and had it fund his summers in 1939 and 1940 running teacher-education workshops. But as When Peoples Meet stalled because it could not find a publisher, Locke shifted back to working full-time on pulling together The Negro in Art. But such segregation of knowledges also meant that no single magnum opus reflected the range, power, and deeper interconnections of his mind.

Shifting his focus to getting The Negro in Art out by his self-imposed publication date of December 15, 1940, Locke dove into collecting the last group of plates. In retrospect, it is hard to appreciate the amount of work that went into creating The Negro in Art. First, there simply was no single repository in the United States that contained all of the images by “White artists,” meaning American, English, French, Spanish, German, and Dutch artists since the fifteenth century who had rendered the Negro form in drawing, painting, or sculpture. For years, Locke had been clipping pictures out of art history books and corresponding with museums, galleries, and private collectors whose names were listed in these books to try and obtain high-quality prints for the book of European, American, and Latin American art. Next, he was hunting down images of art by the young New Negro artists, many of whose work was not in galleries, museums, or private collections. Locke had to visit numerous galleries looking for that work, but also look for work that had been photographed and then cajole the photographer to provide a print at cost. The expressionist images of Norman Lewis were obtained this way after a visit to his New York studio. In other cases, it was even more mysterious. Georgette Powell stated that she had no idea how Locke obtained a print of her work and only knew he was interested in it when she discovered the image in the published book. Here, again, was another sense in which Locke was invisible—he moved secretly behind the scene to achieve his goals unseen by those who should have at least had a glance at what he was doing.

In other cases, Locke relied on the continued generosity of Mary Beattie Brady and the Harmon Foundation, as well as the Baltimore Museum of Art, which had photographed a great deal of art for their exhibitions. Similarly, the last section of the book, the African Art section, required hunting through catalogs, flyers, and making requests of the Museum of Modern Art to obtain those images, perhaps the rarest of all. The work was laborious, but also a labor of love. It was successful only because Locke spent years working as a curator and called on connections he had established over the years to make last-minute requests as he hurried the publication to press.

After Locke had secured color prints of the Hale Woodruff Amistad mural for the centerfold of the book, he sent off a late request to Sargent Johnson, the San Francisco–based sculptor and painter for an image dear to his heart—a modernist, almost primitive, painting of a mother and child done in brown and cream color. Because the request was so last minute, coming literally in October 1940, the frontispiece had to be printed separately from the rest of the book and inserted into each book. Selecting Johnson’s image rather than Winold Reiss’s imagery to open The Negro in Art suggested the journey Locke had taken in the fifteen years since The New Negro. The Negro in Art was a powerful continuation of the argument of the earlier book, but also a step beyond, for instead of a Brown mother and child done in a modernist pose reminiscent of the Italian Renaissance, the new mother and son was folklorist and ultramodernist, a formal emblem of a distinct Black aesthetic from the newest generation of Black visual artists. This book was compiled and written by him alone, and thus he could personalize it with a dedication that encapsulated his life: “To mother, who gave me a sense of beauty that included our racial own.” When the book appeared in December, Locke rushed one of the first copies to Mrs. Mason, who gushed over it. She not only liked the book itself but she also liked the dedication to his mother and, without saying it, his mentioning her own name in the acknowledgments as one of the prime supporters on the project.

Unfortunately, the art book sales were worrisomely slow in January and February 1941. Locke had developed a sophisticated marketing plan for the book, which included preparation of folders that contained information on the book and a handful of illustrations from it to go out to bookshops, libraries, and adult-education groups. He was helped enormously by Mary Beattie Brady and Miss Brown, who forwarded those folders to their contacts and publicized the book through their network. Locke meticulously recorded each bookshop, each local southern public library, and each Negro reading group that ordered the book, and then tracked the payments for those books and where they ended up. Eventually, those records show, The Negro in Art became the most successful of the publications of the Associates of Negro Folk Education. It reached into diverse pockets of interest throughout the United States. Prison systems, to take one example, frequently requested the book, because of the large Black prison population in 1940 and the presence among such prisoners of artists who would be inspired by Negro art across the centuries. So many ordered the book—including sororities and fraternities, local women’s clubs, the Frederick Douglass bookshop, the Memphis Public Library, the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and on and on—that by the end of 1941, the book was a hit.

The Negro in Art was not only a hit with the public. Reviewers, especially art critics, a notoriously dismissive group when it came to art by Negro artists, were overwhelmingly enthusiastic. Walter Pach perhaps summed it up best, “I approached this book with some trepidation, as I expected it to be filled with poorly executed art and with special pleading. Instead, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of work.” Locke had wisely begun the book with the European artists, making the point that the work of Negro artists that followed was part of a tradition of rendering the Negro face and form in art spanning centuries and continents, producing some of the finest art the world had. That was exactly the opposite tack of his work in the 1920s, which had prominently linked Negro artists to the African tradition. That tradition was smuggled into the last section of the book, but it suggested that this was a world tradition of announcing Negro subjectivity through art regardless of the color of the artists’ skin.

Even James Porter had to give Locke credit for the book in his otherwise nitpicky, negative review in Carter G. Woodson’s Journal of Negro History.23 As usual, Porter criticized the linkage to the African tradition, disliked that White artists were the focal point of the book’s beginning, and complained that a focus on the Negro image took away from the freedom of Negro artists to render whatever they felt was their destiny as artists. But even Porter was astounded that Locke had found all of these images, since, as he claimed in his MA dissertation, his work had been limited by his lack of ready access to the images he needed for his analysis. Although Locke’s book did not stress analysis of the artwork, what Locke achieved was showing that Negro artists were part of a European tradition as much as or more than an African one.

Publication was linked to his role as an impresario of New Negro consciousness, a linchpin that justified the work he did creating events, hosting events, or appearing to say a few words at an event, which placed him in the company of people who acclaimed and affirmed his self-worth. Leftists were still the main people organizing these events in 1940. In May, Locke had been in Chicago to attend a meeting arranged around his visit to “encourage interest and develop action around some of the contributions and problems of Negro culture and its advancement.” St. Clair Drake, Ishmael Flory, and Bernard Goss sought to broaden out from the arts to include people from education and the sciences, and Locke was the only person who brought these groups together.24 On September 6, he was in New York to chair a program at which Richard Wright and Paul Robeson would speak, organized by Theodore Ward and the Negro Peoples’ Theatre.25 A kind of incessant energy drove Locke to accept almost every invitation he received lest he become a prisoner of a lonely life.

One welcome invitation came from Louis R. Finkelstein to become a founding member of a new organization of “scientists, philosophers and theologians” that included sociologist Robert M. MacIver and historian Harry J. Carman, both from Columbia; University of Chicago philosopher Mortimer J. Adler; Northwestern University biologist Edwin Conklin; French philosopher Jacques Maritan; and several others who wished to meet regularly to discuss “the preservation of democracy.” This was not linked to the radical wing operative at Columbia, since Finkelstein was a conservative Jewish rabbi and Talmudic scholar. Lyman Bryson, Locke’s long-time ally on the board of the Associates of Negro Folk Education, probably engineered the invitation, since he would serve as the organization’s vice president. The format would combine serious discussions of the thorny issues and challenges to democracy in closed executive sessions for which papers would be circulated prior to meetings, with open debate in public meetings where participants would summarize papers followed by discussions from the floor. The first meeting in September would discuss a paper by Albert Einstein; unfortunately, Locke could not attend. But afterward, he became a regular and eager participant in this unique opportunity—to exchange ideas with the best and the brightest among mainstream intellectuals in positions of power in the American academy. Indeed, the group, later called the Conference on Science, Philosophy, and Religion and Their Relation to the Democratic Way of Life, Inc., would catalyze Locke to produce some of his best writing on cultural relativism and ideological peace, and strengthen the voice of universalism in Locke, already heard in When Peoples Meet and “Ballad for Democracy.” Locke’s thinking as a philosopher would be bolstered by dialogue with philosophers and scientists concerned with why democracy was in danger. Locke would be among the very few in that group who could actually explain why that was.

Locke’s notion of universalism was exemplified that December in the seventy-fifth anniversary of the 13th Amendment celebration held at the Library of Congress. Enlisted at the last minute that fall of 1940 by the newly appointed Librarian of Congress, the radical poet Archibald MacLeish, Locke helped plan the musical program and curated the art exhibit. Relying once again on Mary Beattie Brady for help pulling together a credible art exhibit, Locke was mainly invested in the musical program, especially since he was featured on the program to lecture on the significance of the spirituals, with musical accompaniment by the Golden Gate Quartet. In the storied Coolidge auditorium that had never hosted an event on Negroes, let alone had them speak from the podium, Locke defined for his upper-middle-class White listeners how to read America through the lens of emancipation. “Nothing so subtly or so characteristically expresses a people’s group character as its folk music. And so we turn to that music to discover if we can grasp the essence of what is Negro or, if we cannot do that, at least to try to sample the best of the Negro’s racial experience.”26

His opening sentences on the spirituals laid down their meaning as something formed by the Negro’s racial experience of America. America was a pluralistic universe, because that had been the experience of the Negro in America. The American character was formed by race and the yearnings for freedom, both physical and cultural, that the spirituals embodied in song. The spirituals, therefore, embodied the highest wisdom of the Negro racial experience. “For the spirituals are, even when lively in rhythm and folkish in imagination, always religious in mood and conception … always the voice of a naïve, unshaken faith, for which the things of the spirit are as real as the things of flesh. This naïve and spirit-saving acceptance of Christianity is the hall-mark of the true spiritual.”27 Recognizing that the Negro had no power to change these things in this world, the enslaved developed the fervent belief that there must be a higher power. Their experience of the holy—that “the things of the spirit are as real as the things of flesh”—was “spirit-saving,” since it meant that God recognized the Negro’s essential humanity even though other Americans did not. This experience of the holy, which the rapture of the spirituals expressed, was a universality tied to the Negro’s racial experience.

Locke tried, unsuccessfully, to get And They Lynched Him on a Tree performed as part of the program. But to William Grant Still, Locke confided that Mrs. Whitehall, of the George Whitehall Foundation that put up the money for the event, demanded that Roland Hayes and Dorothy Maynor sing on the program, along with the Budapest Quartet, effectively gutting the budget for anyone else. Locke was terribly disappointed that the choral poem was not performed. Most likely, Mrs. Whitehall did not want her money to fund a choral poem about lynching in a Library of Congress program with her name attached to it. Better to insist on celebrity performers, who were safe. Locke did arrange a performance of Chapin and Still’s work at Howard, which a “small but appreciative audience” attended.

The challenge that eluded Locke so far was to ground his aesthetic politics in a particular local community. Washington would never feel like home for Locke with its Black bourgeois homophobia, its southern devotion to segregation in public spaces, and its clique of Negro artists around James Porter and James Herring who avoided race consciousness in art. Their philosophy of Negro art found its fullest expression in the tiny Barnett Aden Gallery begun in Herring’s home, where Herring and Aden exhibited and patronized international as well as African American artists for decades. Its doors would open to Washington-area artists of all races in 1943, but would not be welcoming to Locke, though he most likely attended some openings. As in New York, he could visit, but never join its community. His heart would always belong to Harlem, but the combination of Augusta Savage and Romare Bearden holding forth in Harlem’s art circles meant that they would never allow Locke to ground his aesthetic leadership there. Some broader opportunities for community activism did emerge late in 1940, when the American Association of Adult Education finally gave him a $3,500 grant to hire a roving proselytizer of Negro adult education in the South. While certainly a stimulus to the sale of the Bronze Booklets and The Negro in Art, it was too late to be the basis of a robust investment of Locke’s time in grass-roots literacy organizing. By 1941, most of the second batch of Bronze Booklets was out of print, and prospects for funding a third edition were dim.

Locke longed for a city in the North where he could feel at home and develop a core of artists, patrons, and tastemakers who embraced his vision of a New Negro art movement of the late 1930s. Locke’s trips to Chicago to curate the art exhibits at the American Negro Exposition in 1940 had reacquainted him with the burgeoning and more accessible visual arts scene there. Collecting work for the Western art exhibit for Barnett had revealed that some of the freshest art of the Negro—the powerful social realist drawings of working-class bodies by Charles White, the elongated modernism of Eldzier Cortor, and the Picassoesque work of Charles Sebree—was coming out of Chicago. There was a vibrant group of local Black women activists pushing for a cultural renaissance in their city, a White aesthete whom Locke could coordinate with, Peter Pollack, and an emerging Black entrepreneurial class whose capital, along with federal funding, might make his contribution pay. Added to that, Locke spent part of the summers of 1939 and 1940 in Chicago running the workshops for the Progressive Education Association/General Education grant. Several of the members of the Science, Religion, and Philosophy conferences were also located at the University of Chicago. The city began to look like a place where he could integrate his voices and become a new base of operations for him.

Of course, Chicago already had a long tradition of Negro artistic production and recognition beginning at least with the Negro Art Week in 1928. But according to Margaret Burroughs, a young radical artist, local artists had no permanent place to congregate, discuss art, and exhibit what they produced.28 A key change occurred when the Federal Art Project (FAP) decided to invest in that community by organizing events to create a real bricks-and-mortar community art center, part of the ideology of art for democracy that suffused the artistic projects of the WPA. Spearheading that Federal Arts Project community art center campaign was Peter Pollack, a liberal, Jewish photographer and gallery owner, who was tapped because his was the only downtown Chicago gallery that had exhibited the work of local Black artists. As he put it in an interview later, he exhibited their work not because they were Negroes, but because their artwork was good, which resonated quite well with Locke’s views.29

Following a pattern of philanthropy popularized by Julius Rosenwald, the Federal Art Project sponsored a community art center if the local communities raised the funding to secure a permanent site. The FAP would supply a director, staff, and technical assistance to run the center, especially its signature feature, art classes that brought art to the masses and provided employment for the artists who taught them. In Chicago, the fundraising effort brought together disparate parts of the Negro community, as the Negro upper class organized several fundraising events such as the Artists and Models Balls. Local Chicago artists innovated more grass-roots fundraising strategies such as the “Mile of Dimes” campaign in which Burroughs recalled standing on 39th Street collecting dimes from passersby until she raised $100.30

Peter Pollack gave hundreds of speeches to diverse groups, White and Black, selling them on the intrinsic value of such a community center in Black Chicago. After one such stretch of proselytizing, he wrote Locke somewhat perplexedly that his audiences were barely interested when he sold the idea as bringing art to the community, but were wildly enthusiastic and contributed funding when the idea of art was pitched as a means of racial progress, both uplifting the Negroes, and creating a dialogue between Whites and Blacks to advance racial understanding. “What do you make of that?” he queried Locke.31

This remark says something about Peter Pollack’s idealism and naiveté.

The center movement … was to us the most essential thing because it was bringing art into the communities. It was bringing art into communities that never saw art. You had dedicated, altruistic people in those days. None of us took any money at the center. We organized the people. We talked, we came with open hands. … “ ‘Here, build yourself a building. We’ll supply you with exhibitions and artists who will teach. We will supply you with a director, we will supply you with a staff of people who will run this thing for you. It’s your structure and it’s your property. You own it. But you must feel that you want it. We can’t go and build it for you, or pay rent for you.’ ”32

But an arts community had already formed in Chicago around the artist George Neal, who had taught art classes at the South Side Settlement House, Jane Addams’s social reform institution in the Black community, where such artists as Charles White, Eldzier Cortor, Charles Sebree, Bernard Goss, and Margaret Burroughs had become powerful, accomplished artists. An informal community art center already met in people’s homes, raising money to send people to the Art Institute for art classes, which is one of the reasons that the fundraising effort of the FAP in Black Chicago succeeded. This local grass-roots effort was driven by the idea that “art was an instrument of social change.” Neal was the unsung hero of this movement, someone Charles White recalled “made us conscious of the beauty of Black people,” who got artists to focus on depicting the local community, its space, housing, and “shacks.”33

While Peter Pollack is usually given the credit for the idea of the community art center in Chicago, even by such art informants as Margaret Burroughs, records from the period suggest that the original idea came from five Black women Chicago activists, “Pauline Kligh Reed, Frankie Singleton, Susan Morris, Marie Moore, and Grace Carter Cole,” who “brought the idea to Peter Pollack, then director of the Federal Arts Project in Illinois and owner of a downtown gallery.”34 A cadre of middle-class Black women activists approached Pollack, who then brought the largesse and institutional power of the FAP to their project and helped them make history. After years of fundraising, in 1940, the committee had raised $8,000 to purchase the former mansion commonly noted as the former home of Charles Comiskey, the owner of the White Sox, on Michigan Avenue, a street and a house abandoned by White flight to Black criminal elements. Once purchased, the Federal Arts Project brought in workmen who restored completely the “rat-infested” house and created an exhibition and teaching community center on the South Side of Chicago.

It could not have been lost on Locke that these Black bourgeois Chicagoans had been able to purchase a building as an art center, while Harlem had been unable to do that to create the Harlem Museum of African Art. Chicago had an entrepreneurial economic base of Black-owned beauty shops, barber shops, funeral homes, hair preparations factories, Pullman porters with disposable income, and newspapermen and newspaperwomen, who, even in the midst of the Great Depression, could buy a building and create the kind of art space he dreamed of.

Peter Pollack was essential in bringing the connections to the New Deal hierarchy that added national legitimacy to the effort. This was notably on display when he secured Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt to speak at the dedication of the South Side Community Art Center in May 1941. That commitment sealed the deal for Locke to attend as well. As Locke wrote to Pollack on March 22, 1941, “Congratulations on having landed Mrs. R. I wasn’t going to miss it anyway, but doubly so now, as I have had several contacts with her and know she is interested in this matter. … She has a copy of the book [The Negro in Art] and was much interested in the Library of Congress show.”35 Once Locke had committed along with Mrs. Roosevelt, Pollack arranged to have their remarks broadcast nationally over the radio. Pollack’s efforts to make the dedication into a powerful spectacle paid off.

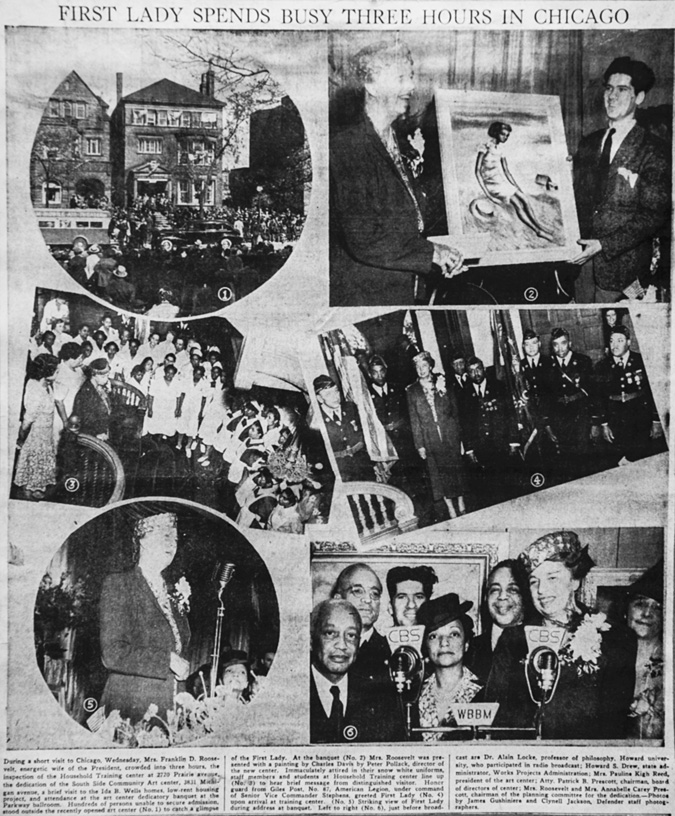

Newspaper coverage of the event reveals that there were multiple non-artistic motivations for Mrs. Roosevelt to attend the official opening of an art center in the Black ghetto area of Chicago. In the Chicago Defender, arguably the nation’s most important Negro newspaper, the photographs of Roosevelt’s visit to the art center were part of a collage of photographs of “Mrs. R” at several other several sites of Negro preparedness for the war that everyone knew America would be entering soon.

“First Lady Spends Busy Three Hours in Chicago,” May 17, 1941. Chicago Defender. Reproduction courtesy of South Side Community Art Center. Courtesy of the Chicago Defender.

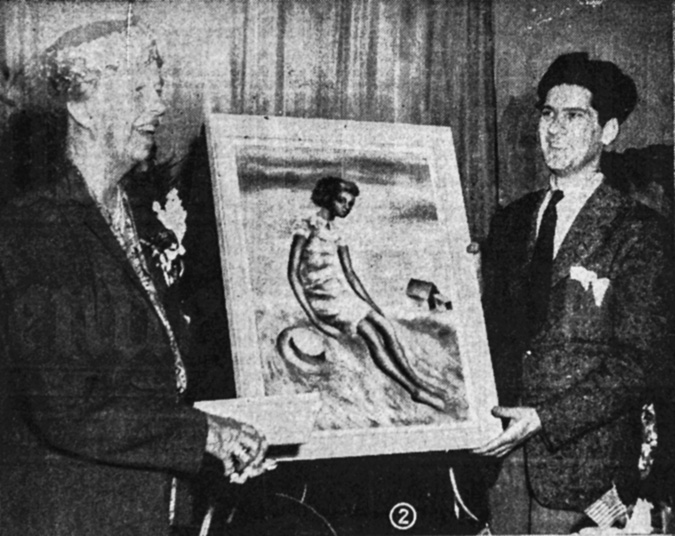

The headline, “First Lady Spends Busy Three Hours in Chicago,” announced that Mrs. Roosevelt “crowded into three hours, the inspection of the Household Training center at 2720 Prairie avenue, the dedication of the South Side Community Art Center, 3831 Michigan avenue, a brief visit to the Ida B. Wells homes, low-rent housing project, and attendance at the art center dedicatory banquet at the Parkway ballroom.” Key to the turnout at the center, for which crowds lined up for blocks, of course, was that she was there. “Hundreds of persons unable to secure admission, stood outside the recently opened art center (No. 1) to catch a glimpse of the First Lady. At the banquet (No. 2) Mrs. Roosevelt was presented a painting by Charles Davis by Peter Pollack, director of the new center. … Left to right (No. 6) just before broadcast are Dr. Alain Locke, professor of philosophy, Howard university, who participated in the radio broadcast; Howard S. Drew, state administrator, Works Projects Administration; Mrs. Pauline Kigh Reed, president of the art center; Atty. Patrick B. Prescott, chairman, board of directors of the center; Mrs. Roosevelt and Mrs. Annabelle Carey Prescott, chairman of the planning committee for the dedication.”36

In his remarks, Locke said that what made this center unique was that “for the first time, at least on such a scale with prospects of permanency, a practicing group of Negro artists has acquired a well-equipped working base and a chance to grow roots in its own community soil.” The idea here was that the artist was the expression of the community’s soil and soul, and that the community found its expression through the artists.

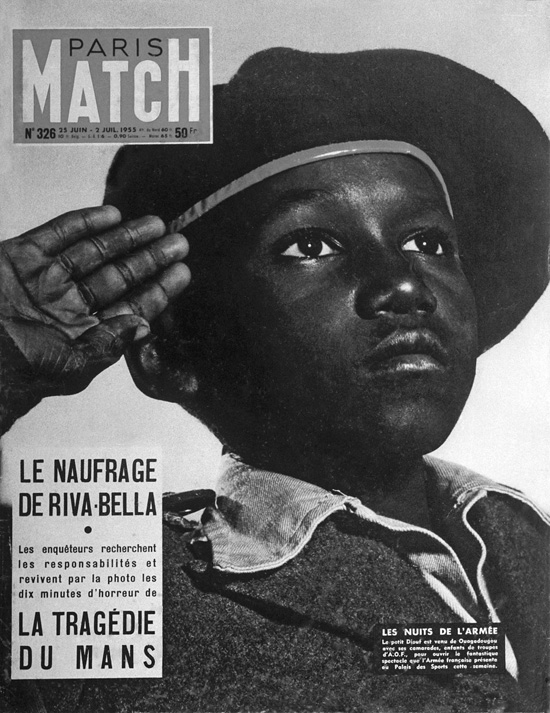

Other aspects of the photographs and the Defender story suggest that art was important, but mainly as a symbol for Roosevelt and the New Deal of Black incorporation into a discourse of American nationalism, even though Locke wanted it to be a symbol of community self-determination through art. Some photographs show Roosevelt meeting with Black women in the WPA Household Training Center and African American honor guard from the local American Legion (No. 3 & 4) marking the impending transition from the New Deal to America’s impending entry into World War II when Black bodies would be important for national mobilization. Standing in uniform with Mrs. Roosevelt performed loyalty to a national mobilization for a global war for Four Freedoms Black citizens did not enjoy at home. The irony of the photographs anticipated the saluting African soldier (No. 5) on the cover of Paris Match that Roland Barthes analyzed as “an exemplary figure of French imperiality.” 37 Locke hints at a similar irony in his address, where he says that there is a double mission here of national affirmation and racial affirmation in the dedication of the South Side Community Art Center. The center affirms the democratic ideal in American art by including the Negro, and it affirms the self-organization of the Negro by having an art center in the middle of the ghetto in Chicago. This double voice is being spoken in the center dedication, which is created out of a democratic impulse of openness to all people, and yet because of the spatial and social segregation of Chicago is really only about Black people. It is shackled by the spatiality of race in Chicago, and yet it is empowered by that structure, because segregation has forced these Black people to pool their talent into one space.

That Peter Pollack was photographed giving a painting by Black artist Charles Davis to Roosevelt, as the guiding hand behind this dedication, is critical to this discourse. Pollack was head of the Federal Arts Project in Illinois and the person who pooled federal resources for the center, which had actually been in meager operation since 1938, when a local group of Black artists and citizens formed the center out of an “art committee.” Pollack got federal dollars to support an art school through the center, which was successful in attracting students long before 1941. He was likely the one who realized that this kind of kickoff event was needed to propel such a center into some kind of notoriety that might give it a chance to survive as the war approached.

A photograph from the event exudes tension: it features Mrs. Pauline Kigh Reed, president of the art center, who was the real director of the center, not Pollack, along with Mrs. Annabelle Carey Prescott, chairman of the planning committee for the dedication, on the other side of Mrs. Roosevelt.

Eleanor Roosevelt and Peter Pollack, May 17, 1941. Chicago Defender. Reproduction courtesy of South Side Community Art Center. Courtesy of the Chicago Defender.

Roosevelt at the Household Training Center and American Legion Post, May 17, 1941. Chicago Defender. Reproduction courtesy of South Side Community Art Center. Courtesy of the Chicago Defender.

Cover of Paris Match magazine, no. 326, June 25–July 2, 1955. ©Izis/Paris Match Archive/Getty Images.

Alain Locke, Howard S. Drew, Peter Pollack, Pauline Kigh Reed, Patrick B. Prescott, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Annabelle Carey Prescott, May 17, 1941. Chicago Defender. Reproduction courtesy of South Side Community Art Center. Courtesy of the Chicago Defender.

A conflict between Locke and the Black women of the center emerged, although its nature is perhaps now lost. Perhaps it was about whether the artists were going to be foregrounded in this discourse or the bourgeois community, who put their money, time, and connections into making this event and the center a success. Perhaps Locke was mad that his friends—the artists—were standing outside the center, while the community, especially the bourgeois fundraising community, was inside. While the center was in many respects the perfect realization of all that he had been working for, he could not build on it. As in the Harlem Art Center, it was commandeered and controlled by local Black women deeply rooted in the local community, bourgeois Black women married to powerful local men. Locke was brought in to sanctify the event, but his presence was reduced to that of a gadfly. Even so, Locke was not about to pass up an opportunity to crack a joke, now lost, and crack up Ethel Waters and other artists there with whom he had a closer feeling.

But Locke hinted at the irony of his marginality and his possible alienation from bourgeois Black cultural politics when he summed up the significance of the center in his remarks: