42

FBI, Haiti, and Diasporic Democracy

On February 20, 1942, Locke walked quickly through downtown Washington, D.C., into the Federal Triangle, the landmark of federal government buildings. As perhaps the shortest adult visitor to the Department of Justice building, the setting overwhelmed Locke physically and psychologically. It was not merely the building’s incongruous blend of Greek revival and Art Deco architecture that made him shudder, but also the irony of the message chiseled into the building: “Justice is founded in the rights bestowed by nature upon man. Liberty is maintained in security of justice.” Locke probably wondered if his liberty was about to be taken from him. He was on his way to the FBI headquarters upstairs, as he had received notice his presence was required to answer questions in regard to information about him that had come to the FBI’s attention. He was anxious to face, if not his accusers, at least their accusations and put to rest, if only temporarily, the extreme worries that had come over him since he received the notice. He knew the FBI had targeted others at Howard University, ever since the 77th Congress had passed Public Law 135 that empowered the FBI to investigate people employed by the federal government suspected of being disloyal to the government. Most of those were known communists. He was not. He also shouldered an additional burden. As a gay man employed at Howard University, he might be considered a security risk because of his sexual orientation. This meeting might out him as a closeted homosexual just as it might charge him with being a traitor. Indeed, in the minds of most Americans, the two were synonymous. An ordinarily nervous man, Locke was beset with more tics and twitching than usual all week. His paranoia in not letting people he did not know into his apartment and changing the name on his doorplate every few weeks had been neurotic preparation for this very day.

Once inside FBI headquarters, Locke learned of the “information” about his “alleged activities” that had been communicated to the Bureau. He was told, “in order that your statement may have particular credence, you will be placed under oath.”1 Then, he was then asked if he had “any objection to” speaking under oath. “No,” Locke answered. “I would rather affirm. There is a Quaker streak in my ancestry.” With a quip Locke had announced that he was not intimidated.

He was then asked whether he was now or ever had been a member of the Washington Committee for Democratic Action. “No sir,” he replied. “I don’t even know of the organization. Can you tell me about the Committee? What is it?” The interviewer, a “Mr. King,” was a bit surprised by Locke issuing the questions. “I am no authority on the organization. It was formed here in Washington, I believe, several years ago.” Locke replied again, “I don’t even know of it.” When pressed as to whether he really did not know about it, Locke expanded on his answer.

That’s why I asked you what it is all about. I get a great many circulars from Liberal and radical organizations, and some of them go into the wastebasket. Usually it is a request to write your Congressman about something that is up before Congress. My name is on a number of mailing lists, but I don’t even identify the organization.

The interviewer then tried to draw Locke into a conclusion he had not made. “If your name was used as a sponsor for this organization, it was used without your permission and authority?”

I would have to see the list before I would definitely—you see, I am under oath and I have to be very careful therefor [sic].

The interviewer continued: “Mr. Locke, are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties?” He denied being a member or having attended meetings of the organization. Again, Locke suggested that in such interviews, it would be best to have information, perhaps letterheads, of the organizations referenced. “You have no idea what stacks of mail one gets from one organization or another. I remember in the case of the Spanish Aid I got so mixed up I didn’t know which organization was what. There were some four or five repeatedly sending to me.”

Here, then, clearly, was Locke’s main line of defense. Overwhelmed by radical mailings, he may have inadvertently associated with some who were considered subversive by the FBI. There were some, however, that he could not deny he was associated with, such as the National Negro Congress. When asked about it, Locke admitted he had spoken before them on two occasions, “attended their meetings,” but was not “formally a member of the National Negro Congress.”

Mr. Locke, are you at the present time, or have you ever been, a member of any organization which you have reason to believe is dominated by the Communist Party of the United States of America, or may be controlled, or its policies dictated by any foreign government?

Locke’s response showed he was fully alert. “Will you repeat that?” The interviewer then stated, “Are you at the present time a member of any organization which you have reason to believe is dominated by … ” Locke’s answer showed his acumen.

No, absolutely not. Not at the present time. The reason, Mr. King, I asked you to repeat that was that I didn’t know the tense, “at the present time.” You see, I caught that when you repeated it. I asked you particularly because of this case. I was interested in and a subscriber to about three of the Spanish Aid societies. There was one of them that I have reason to believe was Communist-controlled. I did not know it at the time, but I became one of the sponsors. When I suspected that it was—incidentally, that was through Mrs. ROOSEVELT’s resigning from the Board. … I investigated the Washington office, and was reassured that it was not. I therefore did not remove my name from the sponsors’ list. About three weeks after that, an issue which came out further confirmed my suspicions, and then I did withdraw, and have a carbon copy of the letter which I wrote to the National secretary.

The interviewer thought Locke was being evasive. “Mr. LOCKE, the question I did ask you was, ‘Are you at the present time, or have you ever been.’ Locke pulled him up short. “In the second reading, you didn’t say, ‘Have you ever been.’ ”

Mr. King was getting a taste of what it was like to try and match wits with Locke. He had to admit he had misspoken (and perhaps misled) Locke when he repeated the question. With the caveat of this one organization, Locke said that he had never knowingly joined such an organization that was communist controlled and had never advocated the overthrow of the government. Suddenly, the interview was over. When asked if he wanted to make a statement, he declined—except to ask: “If there have been specific charges—I am sure there have been—but if there have been specific charges, it seems fair, without divulging the source, to be informed of the nature of the charges.”

Locke’s question was pertinent—why was he being interviewed if it was not illegal to be associated with or a member of the Communist Party? The interviewer hurried to state that Locke wasn’t being charged with a crime, but was responding to information the Bureau had received about him. That left hanging two unasked questions—what exactly was that information and who had provided it?

As Locke left the Department of Justice, he must have wondered if he was being investigated because his name appeared on the letterhead of these organizations, or if someone had informed on him and perhaps included other information on his activities that he had not been questioned about. The FBI, led by J. Edgar Hoover, had been empowered at the beginning of the war to investigate anyone suspected of being a member of a subversive organization or advocating the overthrow of the federal government. The latter claim was ridiculous; even the first seemed preposterous, since Locke saw himself as merely a progressive advocating what was in the best interest of the United States.

Locke had been so careful. The FBI review of arrest records showed he had never been arrested for any crime. Yet it was common knowledge in the Black community that Locke was gay; and now the FBI knew that he had attended meetings, sponsored, and cavorted with organizations that were communist or at least considered subversive by the US government. From now on, he realized, he would be under intensified surveillance: FBI agents would interview his neighbors about him, a copy of the report would be submitted to Howard University, and on one occasion, the FBI entered his apartment and took samples from his typewriter to check whether he had typed certain letters that came into its possession. Now, he would have to be even more careful.

From a sexual standpoint, the surveillance could not have come at a worse time. For the first time in years, Locke had found someone, a young Black man, whom he was really fond of, and the relationship held promise as the long-term love he had been seeking for years. Handsome, lean, and light-medium-brown skinned, Maurice V. Russell was a young man in his late teens when Locke met him, probably on one of his trips to Philadelphia, where Maurice lived with his mother in the early 1940s. Maurice would go on to earn a PhD in social work from Columbia University, work at Columbia, become the director of the Social Service Department and professor of clinical social work at New York University Medical Center, and be an innovator of mental health services in New York. But as a young man, he was sexually ambivalent, lacking in confidence, and needy for a mature male presence in his life. Russell was enormously impressed with Locke. The relationship grew slowly in part because of the enormous age difference and Russell’s ambivalence about identifying himself as gay. Locke had mentored Russell for a couple of years, and it could be said that his educational and professional success were in part due to Locke’s influence. Their relationship was a secret, of course, when Locke began to write the nineteen-year-old. But now the system protecting that secret would be tested more than ever before.

Just four days after Locke’s interview with the FBI, he was penning a letter to this young man. That Russell lived in Philadelphia made it a bit less risky to carry on the relationship, given that the FBI seemed to be tracking his activities in Washington and New York rather closely. Locke could stop off in Philadelphia, on the train between the other two cities, and perhaps not attract the FBI’s attention. Part of Russell’s attraction to Locke, of course, was that he was enormously attached to his mother, a single parent after Russell’s father was killed in a car accident when the boy was seven. Russell’s first letter, a response to Locke’s initial inquiry about Russell’s education plans, outlined this relationship. “I do not believe that I shall get back to school any time soon. You see my mother is partially dependent on me so I have made it my business to support her.”2

Locke replied, “I have nothing but admiration for your manly assumption of a responsibility which came first in my life and should come first in any man’s. Again let me suggest, as soon as you can get adjusted [Maurice had taken a civil service job at the Philadelphia Navy Yard], your taking even just a course or two in evening hours to keep on the track. Training is imperative for everyone nowadays, particularly for the younger Negro. Philadelphia youth haven’t seemed to realize this as realistically as they should. The town is full of nice, untrained but complacent people.”3 The point was still clear: for Locke to be involved with Russell on any serious level, Russell would have to step up and commit himself to educational self-advancement like the older man. Russell did; he began attending night school at Temple after Locke’s encouragement.

Unlike so many of the other young men Locke knew, Russell possessed an inner calm, a personal sophistication without formal training. That sophistication came through in his early letters to Locke that suggested Russell was pursuing Locke as much as the other way around. “I know how you detest praise,” Russell had written in his first letter to Locke, though the letter was a testimonial to how he had admired Locke for years.4 He knew full well that Locke craved praise. At the same time, Russell wanted something from Locke—access to a world of culture, beauty, and “luxury” that he heard in the classical music records that he played before he met Locke. Russell wrote to Locke after an outing together:

Last weekend was truly a memorable one for me! Every moment was well-spent and this knowledge gave me a wonderful feeling when I returned to Philadelphia. Need I describe the thrill of the dinner aboard train or the luxury of the train? Do you think that I shall soon forget the gripping, emotional, grotesque, humorous Porgy? Such acting ability as displayed by the members of our race. How proud we should be of them!

My meeting with Todd Duncan should be recorded—it was the fulfillment of wish of long standing. Thank you so very much!!

What a pleasant surprise to get to see the [Katherine Dunham] dance films. … The beautiful captivating haunting music of the various dance sequences blending the graceful beauty of the dance added the necessary ingredients for complete pleasure. …

The Museum of Modern Art, with its aspect of luxury, aroused any amount of compliments from my limited vocabulary but I was confronted and bothered [by] the question: Do I understand all of this? Do I get the fullest possible appreciation from all of this?5

Russell possessed a hunger for education, culture, self-improvement, and mentoring that he recognized Locke could bring him. That made him an ideal “youth” for Locke, a person he could craft in his own image, and who offered a soul in sync with his own.

Russell was, however, nearly forty years his junior, and like most young men, enmeshed in a circle of friends with whom he shared a life of frivolity and queer merriment quite different from what he had with Locke. That circle of friends could cause problems for Locke. Russell’s initial letter to Locke mentioned that he and “Eddie” might be down in Washington sometime soon. Locke’s response noted that “Eddie Atkinson” had visited the following weekend without Russell. “Barged in with his usual court train, and without previous notice. I was busy on the second installment of my retrospective reviews and just couldn’t stop to entertain them properly.” Having just met with the FBI, Locke was not in the mood to entertain them at all. He was in no humor to hold court with a train of strangers with Atkinson, an over-the-top gay man from Philadelphia, down in Washington to kick up his heels. The queer Victorian rules Locke operated by—prior announcement of a visit being one of them, no strangers brought to the house without asking first being another—protected him from sexual exposure. Russell picked up the hint. Nevertheless, the deeper challenge was Atkinson and his circle of friends, who were at least a generation removed from Locke’s and interested in something other than a “refined evening.” Another member of the “gang” that Locke knew even better was Owen Dodson, another Philadelphia young man, whom Locke had courted. Even after the “elevated” evening with Locke in Philadelphia, Russell had stopped off at Eddie’s where Owen Dodson was visiting. “This meeting with Owen gave me a chance to observe him at least and I feel that he has an intellect that should carry him far. He seems to think a great deal of Owen which perhaps might be justifiable?”6 Locke would make it possible for Owen to study theater at Howard University.

From Locke’s standpoint, the point of his relationship with Russell was to move his focus from this younger group of merrymakers and conceits to deep immersion in culture. Russell agreed with that agenda as well and also seemed to recognize that for some reason, Locke wanted to rendezvous in Philadelphia or New York. Russell helped move that along in 1942 by sending Locke the program for the “Robin Hood Dell concerts,” a summer series of concerts by the world-famous Philadelphia Orchestra in Fairmount Park, in a letter that Russell signed for the first time with only his first name. Locke was positively impressed, viewing this as a sign of greater intimacy. He sent a check for half of the program, though he knew he would be able to make no more than “two or three of them in your good company,” suggesting using the others for “Lenwood [Morris] or some other friend of yours.” He said the programs that “interest me most;—Rubinstein, Anderson, Robeson, the All Tchaikovsky [sic] and the 3 B’s, are special.” Locke clearly appreciated Russell’s gesture, and it prompted an unusual meditation on the frustrations of his life as a Black aesthete and his affection for Jews. “You see youth is my hobby. But the sad thing is the increasing paucity of serious minded and really refined youth.”7

Locke noted that years ago he had had to go to classical music concerts with a young Jew because of his appreciation and reliability. “I used to have two tickets to all the concert series in Washington, but would often have a vacant seat to put my hat and coat on through some student or colleague backing out at the last moment (dance or just carelessness or lateness).” Here is the loneliness of Locke. Refinement like his was generally not of much interest among young Blacks, Locke believed, because of racial prejudice. Russell agreed that “racial prejudice [w]as a possible discouragement to our mutual friends. I feel that it is most definitely a factor that should be listed as a cause of non-interest or lack of initiative.” But this was not an inevitable response, according to Locke, because for him, culture was always a choice, and aesthetics was not just transcendence of a colonial mentality, but a way to reconstruct one’s identity in ways that eluded the erosions of racism. Locke and Russell agreed that “the Jewish boy or girl is never perturbed about such distinctions and in forging ahead so steadily manages to up hold his entire race as well as making a definite niche for himself in this present struggle for the ‘survival of the fittest.’ ” Locke relayed how he had bumped into a young German friend of his with whom he had attended concerts in Berlin and who had come to New York penniless a year ago. This German friend now had a house and a well-paying job. “These Jews,” Locke exclaimed, out of envy at the resourcefulness of those he knew who created their own personal renaissance in America after fleeing the Holocaust. In this comparison, however, Locke seemed to forget that newly arrived Jews in America did not face the same kind of “racial prejudice” as an obstacle to advancement that he had just been discussing or grown up with a narrative of their inferiority in their own country. For Locke still saw the race problem through his own experience of race in America, as an obstacle to be overcome.

Locke preferred to forge an aesthetic companionship with an African American. The ideal still burned in his breast to find the young Black man who would believe, like him, that loving art not only bypassed racism, but contained the possibility for a new social contract in America. Going to concerts was a start. Locke ended his letter by saying that he would discuss details later, perhaps “en route to New York. I have to shuttle back and forth all through the summer on account of editorial work there.”8

That editorial work was for a new special edition of the Survey Graphic that Paul Kellogg had asked him to do in response to the issue of race, Negroes, and the American war mobilization. FDR had articulated the ideology for the war even before the country entered it, in his January 1941 State of the Union Address. Almost as soon as the president laid out the Four Freedoms—Freedom of speech, Freedom of worship, Freedom from want, and Freedom from fear—for which the war would be fought, African Americans made it known that for them these rights were unattainable in America. A. Philip Randolph, having left the National Negro Congress, proposed in 1941 a march on Washington to demand desegregation of the armed forces, elimination of discrimination in hiring, and equal opportunity for Negroes in federal government contracts as the price of full-throated Black support for the war effort. FDR avoided that embarrassing protest in the nation’s capital by issuing Executive Order 8802 that banned discrimination in the hiring in wartime jobs, the awarding of contracts, and established the toothless but symbolically valuable Federal Employment Practices Commission (FEPC), but the Chicago Defender kept the pressure on by announcing a “Double V” campaign—victory in Europe and victory in America—to tie the loyalty of Negroes in war to an expected transformation of American race relations in peace.

Kellogg’s invitation to do this special issue could not have come at a better time for Locke, coinciding with his visit to the FBI. Editing an issue on the race issue in 1942 for a timidly social, reform-minded journal like Survey Graphic gave him a welcome opportunity to show his early 1940s thinking was the logical outgrowth of a New Deal mentality toward race and gave him cover for radical associations that might be considered evidence of his disloyalty. The issue was “safe” in that almost every liberal press outlet was publishing something on the obvious contradictions of America waging a global war in the name of freedom, while restricting the freedom of Negroes to serve in the military only in segregated units. But the contradictions went much deeper than that. Randolph’s threatened march highlighted that while the war was a welcome opportunity to most Americans to escape the Great Depression’s still-lingering unemployment, Negroes were not being hired. Kellogg’s desire to weigh in on this issue reflected his need for the Survey Graphic to be part of the radical conversation about the contradiction of asking African Americans to participate in a war for the “Four Freedoms” when they lacked at least three of those freedoms—freedom of speech, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—in America, especially in the South. The proposed issue also made common sense. Kellogg dared not concede this area of impassioned public debate to his competitors if he wanted his “Calling America” series to be taken seriously as a forum on the burning issues “calling” on America for its attention. Happily, Locke would be reunited with the German artist Winold Reiss to use modernist design to anchor the new debate about race in the 1940s.

Here was an opportunity for Locke to establish his credibility as an American moralist. His lead article set a high literary metaphoric tone for the entire issue. “All of us by now are aware of the way in which this global war has altered the geography of our lives.” Geography, of course, was the key issue of the war as Germany, Italy, and Japan were attempting to take over all the geography of Europe and Asia. Geography also was key to the Negro—when masses took the Great Migration to come north and seize opportunity. Locke was no longer speaking for the Negro, but for America by asking it to make a similar mental shift from “medieval to modern America” in its conception of what freedom really meant. “Americans are reminded enough of that with our armed forces dispersed over five continents and the seven seas and speeding to every compass point of the sky. But even more revolutionary changes are due to take place in the geography of our hearts and minds.” Often, wars produced internal revolution, as World War I led to the Russian Revolution. In America, Locke hints, the roots of revolution were already planted in that mental geography, a “foreshortening” of “cultural and social distance” between Blacks and Whites, but also between goals and practices, because this was a war of inclusion and economic and social integration.

Locke predicted a cultural outcome of the war—a retreat for the forces and ideologies of difference, even those he had championed, and an advance for the logic of integration. Total war would render the strategy of separate racial agendas archaic for both America and Locke, forcing both to try to forge one comprehensive voice. “New forces for unification are closing in on that great divide of color which so long and so tragically has separated not only East and West, but two thirds of mankind from the other third.”9

Was not this issue supposed to be about America’s race problem? In the midst of organizing an issue to speak to how America’s obsession with race prejudice contradicted the Four Freedoms, Locke shifted the analysis to a global context—East and West and the exploitation through separation of “two thirds of mankind from the other third.” This larger perspective shaped how Locke organized the entire issue. “Part I: Negroes, U.S.A. 1942” contained articles, charts, paintings, photographs, and poems on the “Negro in the War” and the “Negro in America”; but “Part II: The Challenge of Color” offered a similar combination of media to show “color” was a challenge in the “New World” of the Caribbean and Latin America as well as the “Old World” of Africa, India, and the Pacific Rim. Certainly, when John Becker, whom Paul Kellogg credited with suggesting the idea for the issue, had imagined a Survey Graphic intervention on this topic, he did not imagine as its focus the large canvas Locke painted for the issue—“Color: Unfinished Business of Democracy”—a discussion of race from an anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist perspective. Maybe this issue was not such a good cover for his radicalizing theories after all.

To fully appreciate how radical Locke’s intervention was, one only has to compare its global perspective with Gunnar Myrdal’s Carnegie Corporation–financed two-volume tome, An American Dilemma, published two years later. Whereas Myrdal framed the “dilemma” as a conflict between America’s “creed”—as embodied in the Declaration of Independence phrase “all men are created equal, with an equal right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”—and American’s practices of racial segregation and discrimination, Locke posed the question in terms of a global issue of the “Colored” people around the globe coming to the aid of self-described “White” democracies about to be overrun by an Axis of racists. In places like French West Africa, it was the African colonial who still was fighting for universal freedom in 1942, while the French in Europe had “accepted defeat and submission to Germany,” as Egon Kaskeline wrote in his article, “Felix Eboué and the Fighting French.” By including this article on a French West African freedom fighter, Felix Eboué, Locke made visible the deeper irony of World War II—that it was the people of color, the formerly enslaved, the currently colonized, who were fighting to free the White people who had enslaved and colonized them for almost a century. Colored peoples’ freedom around the globe was what the war was really about, not the freedom of their overlords to continue the same policies, outlook, and biases that led the world to war in the first place. One would not find that argument in Myrdal’s two-volume excavation of America’s racial schizophrenia.

Also distinctive was that “Color: Unfinished Business of Democracy” foregrounded the subjectivity of the oppressed rather than seeing them as “the problem” to be resolved as Myrdal and others did in his strictly sociological lens. That is because Locke continued his earlier Harlem issue interdisciplinarity by integrating poems, essays, and photographs of people of color from around the world in a compelling montage. “Sorrow Home,” a poem by Margaret Walker, a member of Richard Wright’s Chicago South Side Writers group; “Eternal,” a sculpture by Ramon Banco, the Cuban sculptor introduced to Locke by Mary Beattie Brady; a compelling standing sculpture by Richmond Barthé; and poem from James Weldon Johnson were “much more than the plea of the Negro to America; they speak symbolically for the non-white peoples in a world become circumscribed and interdependent.”10 Perhaps the most telling and humorous part of “Color” was supplied by Sterling Brown, whose collection of Negro comments about the war attested to Black criticality toward US war propaganda: “Man, those Japs really do jump, don’t they? And it looks like everytime they jump, they land.”11

In the intervening years, Locke had learned that the subjectivity he had announced earlier in 1925 was a worldwide phenomenon. In 1925, the global perspective was in the margins, but now it was out front. He had also learned that it was in his interest to allow the criticality of the oppressed to be heard in such forums. Its charts, graphs, and powerful poems and images made visible to the Survey Graphic reader of 1942 that a new world of critically conscious people of color was still coming and that America must deal with them if America was to be saved.

Photographs of Black workers in the war industry gave a compelling sense of the tragic irony of compelling people to work for a democracy that excluded them from its main benefits. And aesthetics allowed Locke to frame the frustration of such a predicament within the same prospect for a willingness to join in the work of democracy despite earlier treatment. The poem “Boy in the Ghetto” by Hercules Armstrong suggested the racially oppressed were willing to abandon their self-destructive behaviors if welcomed into the work of civilization building.

Boy burning with anger—

Shake the violence from your eyes:

Throw that knife in the gutter!

Step where men fight to free

Your world, your dreams.12

The Winold Reiss–designed cover conveyed powerfully Locke’s message that the road forward was through Colored heads brought together by a common world-transforming purpose. This powerful multicolored image of humanity against the backdrop of a world map centered on Africa suggested a global perspective should circumscribe Americans’ subjectivities moving forward. While Locke highlighted the demographic challenge to America’s race biases with dozens of charts, graphics, and photographs, he also showed that color was America’s opportunity. If America got its racial house in order and deployed its democratic values honestly for world citizenship, it could dominate the world. Locke had gleaned what the Roosevelt agenda really was.

This New Deal imperialist argument allowed Locke to slip in his critical mode without eliciting more negative attention from the prying eyes of the FBI. It did not challenge democracy itself as one of the main agents for the perpetration of racism in America and abroad. Under surveillance, contained by the period’s discourse of “win the war first,” Locke was not going to deepen his criticality in the face of a nation that felt the Negro ought to help out. Locke would have to tread carefully in the wake of Color’s success not to elicit further interest from the FBI as being a threat to the American war effort. Remaining invisible was tougher now.

No matter how successful “Color: The Unfinished Business” was at repackaging Black internationalist critique as pressing domestic agenda, it did not make the splash of his 1925 Harlem Survey Graphic. Using the war to leverage greater civil rights as benighted citizen soldiers was quite a different strategy than declaring a New Negro had arisen in 1925. Plus, the Survey Graphic was no longer the vehicle for radical intervention it had been. Well meaning, necessary, and well distributed as this journal was, this twenty-five-year-old Progressive-Era journal had been eclipsed by more radical contemporary magazines raising ire about the Negro’s anomalous position in the war. When the Schomburg Library in Harlem, now headed by Lawrence Reddick, invited Locke and Kellogg to speak about their issue in 1942—a repeat of a similar library forum for the Harlem issue of Survey Graphic in 1925—several other magazines, notably the New Masses, were also presented to speak about their coverage of the same topic. Other people had adopted Locke’s earlier critiques, almost rendering his intervention outdated, especially since his was not connected to a full-throated call for activism. A discourse of democratic inclusion was triumphant, as also evident in James Porter’s Modern Negro Art, published that same year, with its aggressive declaration that Negro art should be nothing more than a province of American art. Locke’s cultural pluralist views were too nuanced for these times.

Nevertheless, Locke kept building his intellectual platform to achieve in 1943 a monumental, if largely hidden, intellectual breakthrough far away from New York. In Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as an official visitor of the Haitian government, Locke articulated an altogether new Black diasporic perspective that redefined his concept of race. The thinking behind his new approach to the Negro probably began with his relationship with Eric Williams, which began sometime in the late 1930s, most likely through his Oxford connections or simply through his desire to secure a job at Howard University. Locke tapped this elegant radical to supply what had been missing from the Bronze Booklets series all along—a book on the diasporic nature of the Black New World experience that would explain the relationship of social processes worldwide that created a Black Caribbean and a West Indian migration to the United States. After agreeing to do the Bronze Booklet, Williams took a trip to Cuba in 1940 to work in the archives there, as his specialty was the British and French West Indies, not the Spanish Caribbean.

The Negro in the Caribbean appeared as the last Bronze Booklet in 1942. Its central argument was a Marxist explanation of the economic issues that determined the course of slavery and its after-effects in the Caribbean. Locke also included an article on the Caribbean by Williams in the “Color” issue of the Survey Graphic that condensed The Negro in the Caribbean into a pithy contribution to Locke’s global approach to race in America. When published in 1944 in the book Capitalism and Slavery, Williams’s insights would overturn the historiography of slavery, for he would argue that economic considerations, not moral conscience, led Britain—even its abolitionists—to end the slave trade. England’s suppression of slavery was competitive—to crush its rivals in France, Spain, Holland, and of course America, still dependent on agricultural production by slave laborers. Locke’s editorial work with Bronze Booklet scholars to shorten, simplify, and sharpen their writing may have helped Williams to transition from his cautious Oxford dissertation to the boldest presentation of his unique thesis. Also important was the impact of working with Williams on Locke. Under Williams’s influence, Locke thought through how different hemispheric slavery regimes resulted in different post slavery Negro social formations, a diversity of Negro subjectivity in what Locke would later call the “Three Americas.” Fortunately for Locke, one of those “Three Americas” was calling him.

Locke may have begun planning the lecture trip to Haiti as early as 1939, perhaps an outgrowth of that Haitian minister’s interest in Haiti obtaining Jacob Lawrence’s Toussaint L’Ouverture series when it was exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Art. That year Haiti organized its national library, the Bibliothèque Nationale d’Haïti, a symbol of growing national pride and self-consciousness about Haiti’s literary and cultural contributions to world culture. Although the purchase of Lawrence’s series never took place, the Lawrence discussions may have led to conversations with Locke’s long-time friend, Dantès Bellegarde, the dandyish Haitian intellectual and foreign minister to Washington, who encouraged increased intellectual contacts and exchanges between Haitian and African American intellectuals. When Élie Lescot was elected in 1941 as president of Haiti, the invitation materialized as part of Lescot’s agenda to heighten the country’s national and international prominence by inviting cultural leaders to talk up its cultural significance. Locke seized on this opportunity to develop a unique theory of the cultural nature of the African Diaspora in the “Three Americas.”

Most Diaspora thinkers focused on how oppression had driven a people from their homeland into satellite communities linked by their common origin and argued salvation through a return to a holy land—either Palestine in the Jewish Diaspora or Africa in Marcus Garvey’s imaginary. But a unique notion of the Diaspora had been implicit to Locke’s thinking ever since 1925 and his Harlem article in the Survey Graphic. There, Locke posed Harlem as the reversal of the historic forced migration of the Atlantic slave trade by choice to found a New Jerusalem in a new place, where the main effects of the forced Diaspora could be reversed and the race reborn. “Hitherto, it must be admitted that American Negroes have been a race more in name than in fact, or to be exact, more in sentiment than in experience. The chief bond between them has been a common condition rather than a common consciousness; a problem in common rather than a life in common.” In Harlem, the dismembered parts of the African body came together in “the first concentration in history of so many diverse elements of Negro life.”13 Harlem was a magneto drawing dispersed people together, rather than apart, into a new future, a reintegration as a race, ironically not in the Caribbean or other diasporic peripheries, but at the center of New World capitalism, New York.

Locke believed the healing process, which is what the New Negro represented psychologically, was started by coming to Harlem, but required a racially conscious art to complete it. Locke knew that the effort to mirror a fully sutured self in the Negro Renaissance literature had also failed. Partly, it was the weakness of the artists. Partly, it was the Great Depression that had prematurely shortened the Harlem Renaissance. But partly it was America, whose powerful counter-force to racial self-determination—Whiteness—created a desire to assimilate into the body of America without reservations. In various ways, Locke had struggled to define the alternative—a separate Black body, an appendage, an American body that was essentially Black, and so on. Although Locke had made that a transnational body through his own “practice of diaspora” to Black Europe, working with the Nadal sisters and others, for example, to translate The New Negro into French, or through his associations in Africa with trips to Egypt and with King Amoah, he had avoided until now the opportunity to extend it to the Caribbean, except for his brief sojourn with his mother to the Bermuda.

Locke began to gravitate toward a hemispheric diasporic perspective in the 1940s, following an intellectual path charted by African American women artists, especially Zora Neale Hurston, Katherine Dunham, and Lois Jones, who visited and even moved, in some cases, to Haiti and other Caribbean nations to develop artwork based in Africanisms stronger there than in the United States. For these artists, Diaspora was both a cultural strategy to connect with Africa and a way to reinvigorate African American cultural formations by connecting them with Caribbean aesthetic and religious traditions where Africanisms flourished. These artists innovated a second notion of Diaspora, not the flow of bodies, but the flow of ideas, northward. For them, Diaspora was both resource and muse. Hurston, for example, completed writing Their Eyes Were Watching God in Haiti.

Howard University’s transformation from an institution to train students in liberal arts education to an institution for the production of critical knowledge was another important influence. Ralph Bunche, E. Franklin Frazier, Sterling Brown, Abram Harris, and now Eric Williams had made research on the African Diaspora more important than it had been in the past, even if that was not their main focus. This second generation of social scientists and artists were “integrationist scholars,” to be sure, but their excavation of the political, sociological, and economic processes undergirding Black life instinctively tied the study of African Americans to worlds beyond the United States. Ralph Bunche’s Harvard doctoral dissertation was on the African mandates system, the one Locke had studied ineptly in 1928. Frazier advanced the theory that the survival of Africanisms in African American life was minimal, but in the course of his running debate with Melville Herskovits on this issue, he won a research grant to study African survivals in Brazil. And Eric Williams brought a global systems approach to Diaspora and Caribbean thinking—a criticality toward Latin America, its race and economic structures, and the suffering experienced by people even under the “Latin code” of race relations, as it was termed, south of the American border. Howard’s emphasis on political and sociological analysis of the differences and similarities among North America, the Caribbean, and Latin America suggested that the sociologist in Locke could find ample materials for a more global theory of the New Negro by developing a diasporic theory of his own in his Haiti lectures.

Locke almost did not get the opportunity to give the lectures. Invited originally to give the lectures in Haiti in 1942, the federal government refused to issue him a passport when he requested it early in the year. Haiti had become strategically important, as Eric Williams mentioned in his Bronze Booklet, when a rumor circulated that Hitler had plans to invade America by seizing the Caribbean with his U-boats. Although it was later clear that such a plan was preposterous, that did not stop Life magazine from publishing a series of maps in March 1942 that outlined how the enemy might force its way into the Western Hemisphere through the Caribbean and enter the southern United States by way of the Gulf of Mexico.14 The federal government not only took that threat seriously but had also already intervened in Haiti’s internal affairs in 1941 to pressure its president to resign to make the way for Elie Lescot, whom US officials believed was more likely to advocate economic policies to help American wartime interests. The expectations of help turned into policy that the heirs of the slave trade and colonialism ought to assist America and its war allies remain, ironically, free to determine the political and economic destiny of the unfree. The federal government also was serious about Locke as a security threat. After all, Locke had made numerous trips to Germany even after the Nazi takeover in 1934. He was accused of being on the boards of known communist-front organizations. Could he be going to Haiti on a mission other than cultural exchange? By the fall of 1942, Locke had cancelled his request for the passport, as it was not going to be granted that year. In early 1943, he made another request, perhaps after some indication from the government that it might allow him to go after all. After some maneuvering, he was able to get Haiti to invite him again and obtain another leave of absence from Howard for the spring quarter of 1943. Mercifully, the US government issued his passport.

Fortunately, Locke had been working on the lectures, having produced an outline as early as October 1941. There was then the matter of having them translated into French. At first Louis Achille started translating them, but Locke then had to seek out another translator to finish the job. The six lectures documented the contribution of the Negro to the various societies of what Locke called the “Three Americas”—North, South, and Caribbean societies shaped by slavery. He suggested that the pivot of democracy, as he had argued in “Color,” was each society’s treatment—legal, political, and social—of the Negro in its post slavery formations. His first innovation of the lectures was to chart a new direction for Diaspora as a dialogue among societies shaped by the Atlantic slave trade and the Negro, a dialogue over differences as well as similarities among those societies, with an emphasis on what was distinct in each and what each could learn from the other. The co-sponsors of the trip prompted this diasporic adventure, as Locke acknowledged in characteristically ironic voice, when he noted:

Your [American] Committee [for Inter-American Artistic and Intellectual Relations] has saddled me with a difficult task. I was sorely tempted to buck off half the load on the plea that the Negro problem of the United States was back-breaking in itself. However, on conscientious thought, I discovered underneath my feeling of protest the incorrigible human trait of habit: I was sniffing at familiar cats and pulling toward the accustomed stall. But the more I reflected on the matter, the more welcome the subject became in the wider perspective of the original assignment. In discussing the Negro in terms of both North and South and Central America, we not only have the benefit of certain important but little discussed contrasts, but can use the wide-angle comparison as a more scientific gauge and a more objective yardstick for measuring both the historical and the contemporary issues of the American race question.15

The assignment had forced Locke to develop a more nuanced theory of Negro identity formation as a global dialogue than he otherwise would have done. That spoke to the larger reality of Locke in the 1940s—despite the hurts, the frustrations, the disappointments of his life, he still possessed the capacity to react to his experience and turn its challenges into new ideas.

Locke developed a contrastive analysis of the New World societies that had emerged out of the Latin or the Anglo code of race relations in his lectures and deployed a new set of insights of how different norms of interracial relations under slavery had produced positive and negative consequences for Negro social formations in slavery’s wake. Each system had its benefits; and Locke dispelled the notion that coming up slave or free under the Latin code was more humane than living under the English. Instead, using E. Franklin Frazier’s analysis of South American race relations, Locke argued that the Latin code transferred to color and class conflict internal to the Negro group what had remained as racial and external conflict with Whites in the North American society.16 The bane of the North American system was its rigid insistence that one drop of Negro blood rendered the bearer Black and relegated to the most intense of segregationist systems of exclusion and penalty to those so labeled. But the bane of the Latin was that it granted mulatto descendants of the interracial unions a special status below that of Whites but above Blacks. Over time, this mulatto class became an elite sphere of influence that refused to see itself as connected to or representative of the Blacks as in the United States. Racism English-style had been the cruelest form of New World social relations but had its unforeseen benefit: the educated, the talented, and the favored, and the pure Negro and mixed-race, penalized equally in the law, became a powerful political and cultural voice of the Negro community as a whole.

Locke showed his modernity by taking an airplane to Haiti. In 1943, flying on an airplane was something not many people would choose to do, as Mrs. Mason acknowledged when she wrote him later, “My brave boy flying on wings of truth to Haiti!” It was also wise from Locke’s perspective, for as he quipped in a letter to a friend, “I didn’t want to become shark’s bait because of Hitler’s U boats!” Locke landed safely in Port-au-Prince on May 1, and was whisked to the Hotel Oloffson, the most sumptuous hotel in town.17

But on arrival, Locke got wind that there might be trouble. He was informed that his analysis of racial formation in the Western Hemisphere might discomfort the main audience of his lectures, President Lescot and the Haitian government. Lescot had staffed that government largely with friends and acquaintances from his own mulatto class, and he emphasized that Haiti’s future success depended on it being led by an elite drawn exclusively from that class. His Haitian benefactors expected Locke to provide the kind of paean to Haiti and its African retentions and status as a resource that other African American artists had mined for their art. Certainly, Locke acknowledged that African Americans had much to learn from Haiti and that a dialogic approach to Diaspora meant a much longer list of Black writers, artists, and playwrights from which to make his Negro contributions to American cultures. But by the 1940s, the sociological voice, the voice of Black criticality, had led him to ground his cultural analysis in commentary on the social contradictions under which diasporic cultures breathed and lived. This line of analysis exposed that people living in Caribbean nations favored by the Latin code were crushed by a color and class oligarchy that made Blackness a badge of internal oppression in so-called postcolonial nations.

As he wrote to Maurice Russell, at the opening reception all of the “Haitian and American dignitaries [were] present and all the critics keen for the occasion, you can imagine it isn’t easy even for a veteran.”18 The assembled Haitian elite would not be pleased to hear their country’s current political direction and social conflict aired as dirty laundry in his lectures. Hurriedly, as he confided to another friend, Arthur Wright, Locke rewrote his lectures “when I sensed the situation.” He then contracted with a local translator to retranslate them before each lecture. Locke was nervous not only because he treaded on delicate territory in his lectures but also because he delivered his remarks in translated French. More than eight hundred people came to hear his first lecture, graced by the “dramatic entrance of the President and staff and a click heel presentation before and after the [United States] Ambassador and staff [entered]. [I]t was enough to make me nervous, even outwardly so.” That was not surprising. A verbal slip or a wrong phrase could offend a listener and cause an international incident. What Locke had imagined as a welcome vacation from teaching had turned into a trying assignment to speak truthfully about the diasporic situation of the Negro without alienating his listeners so much that he could not be heard—or leave unharmed by the experience.19

Locke was up to the challenge. After years of fine-tuning his controversial messages to White American audiences, Locke possessed the rhetorical strategies to convey his points without his audience often noticing how devastating they were to their subject position. Evidently, President Lescot was pleased, hosting a lavish dinner for Locke on Palm Sunday and arranging for Locke to fly by military airplane to the citadel at Christophe. Lescot got what he wanted out of Locke’s visit, part of what one critic later called Lescot’s strategy of inviting distinguished lecturers to the country during World War II, wining and dining them, and conferring on them honors—Locke was awarded the nation’s Legion of Merit at the final ceremony—to get their assent for his government that maintained “low living standards for the masses, bitter poverty for the peasants, puppet politicians, color and class divisions, which help the foreign exploiter, and a ‘cultural crusade’ to hide the hideousness which lurks behind the cultivated facade of its mulatto elite.”20

Locke seemed to realize that he was being used. But there were unexpected benefits. Visited by disaffected Haitian students, who had heard the hidden criticality of his message, they shared with Locke “private memoranda on color prejudice between the upper class mulattos and the black peasantry, which in my judgment was more of a tribute than the decoration which the President gave me.”21 Such students would be the major force in launching a student strike and a series of street demonstrations in 1946 that eventually deposed Lescot and installed a Black cabinet.22

Locke’s dialogic theory of Diaspora was itself an attempt to teach the Haitian nation how to become modern. Lescot could not see that, using Locke to legitimate what he was already doing, instead of viewing him as an opportunity to collaborate on rethinking the social direction of the Haitian nation. In proposing an inter-American diasporic dialogue, Locke was asking whether the life of the people in one particular country can be improved “by borrowing from each other what is working to improve democracy” in the other country. Influenced by Ralph Bunche, Locke suggested the diasporic Negro could gain from invoking the Anglo-American notion of fair and proportional representation as key to democratic legitimacy, something that if acted upon in Haiti would have led Lescot to democratize his cabinet without needing the revolution of 1946 to depose him. Here, without mentioning Eric Williams by name or his critique of the treatment of agricultural laborers and the poor in the Caribbean, Locke suggested that a dialectical relationship must be insisted on between cultural and social democracy, or an anomaly would result. The struggle for political and cultural representation in the Western Hemispheric imaginary, he contended, should be the rationale for a postwar consciousness movement in the Three Americas.

The most revolutionary part of Locke’s Haiti lectures was not the most controversial. Indeed, it went completely unnoticed in the charged atmosphere about the caste and color issues of which he argued that a new kind of America was possible in the Western Hemisphere based on Diaspora. Diaspora, in other words, was the key to a new internationalism. Equality between nations, races, and cultures was the next necessary step in the evolution toward diasporic democracy that would not become real at the political level in a satisfactory manner, Locke argued, until spiritual and moral convictions could be used to govern just and lasting relations between different human groups. Implicit was a call for the Negro in the new diasporic conversation to transcend both race and nationalism.

Locke’s dialectical pragmatism allowed him to advance race consciousness, at the early stage of his lectures, as a benefit to the North American Negro’s sense of community, but then argue later that even that stage must be transcended if the true realization of democracy as a shared inheritance was to erupt in the Three Americas. Transcending race meant transcending provincialism and national identification. True diasporic consciousness could only develop through the transformation of those provincialisms, deeply rooted in these various cultures, into something that moved beyond race and kinship loyalties as the basis of community. Those provincialisms created proud feelings of exclusivity and superiority, but they also led to degrading some other subjectivity or excluding some other people from a larger diasporic perspective.

Locke argued that a truly diasporic view of the Caribbean required the Negro to take into account the large “Indian population” and the “large East Indian or Hindu populations” that were also part of the Caribbean. A real inter-American dialogue about race and culture must take into account the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean displaced by colonization and acknowledge that the African was not the only Diaspora to the Caribbean. Although Locke did not detail the history in his lecture, he was clearly referencing that “large East Indian or Hindu populations” existed in Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and other Caribbean nations because of their forced migration to the Caribbean by British capitalists, who needed cheap labor for the sugar plantations after slavery was outlawed in 1833. While not technically slaves, they endured similar conditions of forced labor, malnutrition, and early death, and now constituted a “large population” in some Caribbean islands. A dialogic approach to social formation in the Caribbean had to appreciate the “polyracial character of our Continent as more crucial and critical in our inter-Continental life and its progressive development than in even our respective national societies.”23

This was the stroke of genius in his diasporic theory of community formation: if Diaspora was the basis of our notion of community, then all of those who had migrated into the inter-American theater of culture and society or been displaced by such migrations must be included in the dialogue about the future. Such inclusive thinking means acknowledging and facing the differences in our histories and experiences as well as learning from our shared realities. Those displaced by diasporas (the native inhabitants) and those who have come through other diasporas (the East Indians) must be part of the inter-American conversation in order to avoid reproducing the same provincialisms that spawned the existing racial nightmare. This is what the North American attitude had to learn from the “polyracial” nature of the Caribbean.

This universalism came from a capacity found in African Diaspora art, Locke naturally argued. The spirituals had always been fundamentally universal; they just had to be labeled and promoted as Black art because under the Anglo code of race, the official culture denied Negroes any humanity or pride in their cultural fecundity. He and others had had to advance African-derived cultural products as racial armor, but the spirituals expressed the yearnings of all people for deliverance from suffering regardless of race or national origin. Such art was a gift to the world from the inevitable mixing of cultures that the Diaspora produced. Negro culture possessed within it a diasporic universalism that could become the basis for the disparate countries of the Western Hemisphere to write.

Perhaps a twentieth-century global consciousness could begin with the Negro. What Locke suggests is that the diasporic peoples of color begin to form an international federation, a kind of United States of the Americas, by beginning the practice of mutual exchange and positive regard of one another, and create the conditions to welcome others, Whites, into that. Some steps in the direction of a racially self-conscious Latin American formation had occurred already in Brazil, which had witnessed the emergence of a Frente Negra Brasileira (Brazilian Black Front) in 1931. What Locke was advocating was to extend the notion of community he had first announced in Harlem in terms of the New Negro into a New Diaspora—a new subjectivity and a new sense of community that allowed Black, Indian, Hindu, and others to enter into conversation about their experiences of colonialism, White supremacy, and new-world diasporic migrations, and lay the groundwork for a new inter-nation collaboration. A new diasporic community might emerge with a unique sense of hemispheric culture and democracy without limitation of country of origin or present residence.

This was heady stuff that most likely went over the heads of Lescot and his Haitian government cronies and even the people at the Guggenheim Fellowship and the State Department, to whom Locke had to report after returning to the United States. But few in America, let alone in largely impoverished locations in the Black hemispheric Diaspora, could enact what Locke recommended. That was brought home to him dramatically that summer of 1943 when, during a brief stay over in New York, he walked out of the Hotel Theresa and right into the Harlem Race Riot of 1943.

Unlike the 1935 Harlem riot, Locke experienced this one live, as Black people ran, smashed store windows, stole goods, screamed and laughed hysterically, and set buildings on fire. Locke feared physical violence and, even though these were Black people wreaking havoc mostly on White businesses, it roused in him first fear and then confusion, as if he could not believe his eyes. Suddenly, all of his theories about the historic patience of the Negro with all manner of racial and economic degradation in America, or about art as a catharsis to alleviate the centuries of pain, were rendered irrelevant as he witnessed the violent self-destruction of the very community, Harlem, he had so celebrated for almost twenty years.

Of course, this Harlem was a different Harlem from that of 1925. It was beset with continuing economic unemployment despite Executive Order 8802. It was struggling with more decrepit housing scarcity than in the 1920s. It had limped through the worst depression in American history. And, it was angry Black men and women being sent to fight the Germans, the Italians, and the Japanese, while those on the home front still endured crushing poverty and discrimination. Locke realized the rioters were a far cry from the self-conscious race-proud New Negroes he had worshipped in print eighteen years earlier. Or were they? Were these rioters not self-conscious and cognizant that the only way to get the attention of New York and the nation was to destroy their neighborhoods and the businesses that regularly overcharged them, in an act of liberation? Locke was confused about what this riot meant, having realized, painfully, how inept his earlier understanding of the 1935 riot had been. Harlem’s catastrophic decline finally sunk in, as he experienced a deep sense of loss that horrific night.

The riot, coming so soon on the heels of Locke’s forecast of the possibilities for what could be called a Diasporic Renaissance in the Western Hemisphere, confounded him. His social theorizing never adequately addressed the powerful pull toward anomic rebellion in the lower- and working-class urban communities of the North. A contradiction persisted between his conception of what that updated Renaissance might look like and the quality of life actually experienced by the Black masses. This highlighted the tension between the purely discursive and often brilliant innovations of Black intellectuals and artists and the still soul-destroying social and economic conditions under which rank-and-file Black people suffered despite those brilliant innovations. Locke’s democratic and diasporic theorizing flourished, but the people he theorized about languished.

The violence of the Harlem riot thrust Locke into a deep depression. Weeks later, after conveying his experience to Kellogg, the editor had asked Locke if he would write up his impressions for a sequel to his 1936 article, “Harlem, Dark Weather Vane.” But this time the vane was too dark. Locke tried to write something, but in the fall of 1943 confessed to the editor that he was too deeply disturbed to write about it professionally. He had nothing to say. Or perhaps he could not say what he felt to a public fed on his optimistic, concluding sentences. Words could not capture his disappointment at where the material conditions had led the Negro—and that there was no uplifting catharsis on the horizon, only horror.

When three years later, Locke heard the news of the military coup in Haiti that deposed his benefactor, he must again have been saddened. He had tried to tell the self-congratulatory president of Haiti that a major change was required to keep legitimate power, but Elié Lescot had not listened, just as American leaders had not listened when he wrote in the 1942 Survey Graphic that America was at the breaking point since its democratic values were so plainly contradicted by its racist war mobilization. The streets of Harlem no less than the streets of Port-au-Prince were crowded with hapless Black boys and girls without a place to go in the national imaginary. In that sense, the inter-American diasporic conversation Locke had forecasted in his lectures was taking place. But it was saying something much darker and destructive than anything he could bring himself to say.

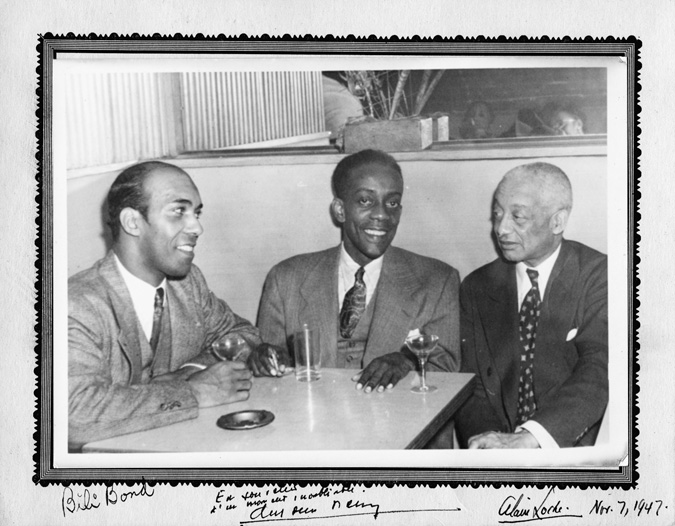

Bili Bond, unidentified man, and Locke, November 7, 1947. Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.