5

Montgomery

As the riders were stuck in Birmingham awaiting a bus to Montgomery, Governor Patterson had stated, “We are not going to escort those agitators. We stand firm on that position.” After a night of swearing and shouting, he and Robert Kennedy came to an agreement. Patterson had been one of the few Deep South governors to support John Kennedy’s presidential bid in 1960, but that political relationship was now ruined. However, Patterson promised to keep the riders safe. Robert Kennedy sent Seigenthaler and John Doar, the assistant attorney general for civil rights, to supervise the protection. City of Montgomery Police and Public Safety Commissioner L. B. Sullivan and acting Police Chief Marvin Stanley told Patterson, Alabama Public Safety Director Floyd Mann, and the FBI that a group of policemen would await the riders’ arrival in Montgomery.

Birmingham police escorted the riders until their bus passed outside the city limits. There the Alabama Highway Patrol, under the direction of Floyd Mann, took over. State trooper cars were stationed every fifteen miles along U.S. Highway 31 the ninety miles between Birmingham and Montgomery. The bus was flanked by motorcycle troopers and cars with news reporters. A small surveillance plane flew overhead.

Sirens blared and lights flashed as the bus sped down Highway 31, but inside the drive was relaxed and even pleasant. Few spoke. The riders assumed they were finally inside the protection of law enforcement.

But as the riders entered Montgomery, the state trooper escort peeled away so the Montgomery police could take over. But they were nowhere to be seen.

Arrival at the Montgomery Station

The Greyhound bus proceeded uneventfully into downtown Montgomery. William Barbee had driven ahead separately and was waiting at the station. Meanwhile, John Seigenthaler and John Doar had stopped for gas, coffee, and a leisurely breakfast. They expected the riders to arrive around 11 a.m. because state officials had assured the Justice Department that the bus would make its usual stops. Unbeknownst to the two Justice Department officials, the bus had sailed past all other Greyhound stations south of Birmingham.

At 10:23 a.m., the bus arrived at the Montgomery station at 210 South Court Street, the driver opened the doors, and the twenty freedom riders disembarked. The scene was eerily quiet and the station was almost deserted. A group of reporters stood on the platform, and a dozen white men stood near the terminal door. A few taxis were parked along the street. John Lewis remarked to William Harbour that the situation didn’t feel right.

NBC cameraman Moe Levy stepped towards Catherine Burks and Life magazine reporter Norm Ritter asked Lewis a question. Lewis didn’t have time to respond. When Ritter saw Lewis’s expression, he turned around to see about two hundred white men, women, and children pour out of nearby buildings and alleys. Like the mobs in Anniston and Birmingham, this crowd carried makeshift weapons including hoes, rakes, hammers, ax handles, boards, bricks, chains, sticks, whips, tire irons, baseball bats, ropes, rubber hoses, hammers, and heavy purses.

The journalists, including Time magazine correspondent Calvin Trillin, were the first to be attacked. Few photos of the melee survived. A Klan member (who turned out to be an off-duty police officer) clenched a cigar in his teeth as he beat Moe Levy with his own camera and kicked him in the stomach. Life photographer Don Urbock’s camera was ripped off his neck and smashed into his face.

A middle-aged white woman stirred up the crowd by repeatedly shouting, “Get them niggers!” Another voice yelled that Montgomery would never be integrated. The crowd screamed that the whites were “nigger-lovers” and hurled accusations of communism.

Backed up against a wall, Lewis said, “Stand together. Don’t run. Just stand together!” He and the other black riders tried to protect the white riders, but Jim Zwerg was pulled into the mob. Zwerg said he asked God to be with him and “to forgive them for whatever they might do,” and felt the “greatest spiritual connection of his lifetime.”

Men beat Zwerg in the mouth with his own briefcase. They shoved him to the ground, trampled on his torso and head, and pulled him up again to pin his hands behind his back and continue the assault. The crowd beat him into unconsciousness, but even then they put Zwerg’s head between someone’s knees and punched him in the face. Women struck him with bags and held up children to claw his face.

The intense focus on Zwerg gave other riders a chance to escape. Allen Cason, Fred Leonard, and Bernard Lafayette jumped over a retaining wall between the bus station and the adjoining federal courthouse and post office and fell eight feet onto a concrete ramp. They then ran through the back door of the building’s basement mail room, startling mail workers.

Lucretia Collins jumped into a taxi and observed the assault on Zwerg until she could no longer watch. The other women also got into the taxi, but the black driver was afraid to let the two white women ride in his cab due to the segregation laws. Catherine Burks told him to move over so she could drive, but he didn’t budge. So Susan Wilbur and Sue Hermann stepped out, allowing the five other women to get away.

Wilbur and Hermann found another cab, also with a black driver, but a white man yanked the driver out of the car and the women were pulled into the mob. At this moment, Seigenthaler was driving around the block. He pulled up to the curb when he caught sight of what he called “an anthill of activity.” A skinny white teenage boy posed in a boxing stance was punching Wilbur until she fell on Seigenthaler’s fender.

Seigenthaler leapt out of the car, grabbed Wilbur, and yelled for her to get in. Hermann escaped a group of taunting men and pocketbook-wielding women and dived into the backseat. But Wilbur, having no idea who Siegenthaler was, pushed him away and told him this wasn’t his fight.

Two white men asked Siegenthaler who he was. When Seigenthaler announced that he was a federal official, a third man hit him in the head with an iron pipe. The mob kicked him under his car’s rear bumper, where he lay unconscious and unnoticed for twenty minutes.

John Lewis, who was trapped near Zwerg, had grown up in nearby Troy and was familiar with Montgomery and tried to shout directions to the other riders. The mob rounded on him, ripped his suitcase from his hands, and knocked him out with a wooden Coca-Cola crate.

William Barbee also did not escape. The crowd pushed him to the ground, and stomped on his shoulders and head. Three men held him down, rammed a jagged piece of pipe into his ear, and hit him in the head with a baseball bat.

The crowd spat and screamed, “Hit them! Hit them again!” A local African American bricklayer walked into the mob and said that if they wanted to hit someone, they should hit him. They did.

Fred Leonard described the crowd as “possessed.” The usually calm John Doar was by now watching the horrific scene from an overlooking window in the adjacent federal courthouse and was on the phone with the Justice Department’s Burke Marshall back in Washington. Doar urgently narrated: “There are fists punching . . . It’s terrible . . . There’s not a cop in sight . . . It’s awful.” Huntingdon College student George Waldron heard screams being broadcast live by a local radio station and thought that the mob was killing the riders. A Birmingham-based news reporter said that the “terror” in Birmingham didn’t compare to this: “Saturday was hell in Montgomery.” Many of those present would long remember the day as an expression of animalistic madness.

Alabama State Public Safety Director Floyd Mann had no jurisdiction inside the city limits, but when he arrived and saw that there were no police present, he called troopers. Though he described himself as a moderate segregationist, Mann said he still believed in enforcing the law.

Mann pushed his way into the grasping crowd, located Lewis and Barbee, and fired his gun in the air. (Other riders, not realizing who Mann was, heard the shots and feared the worst for Barbee and Lewis.) Mann pulled men off Barbee’s body and said, “I’ll shoot the next man who hits him. Stand back. There’ll be no killing here today.” He also saved the bricklayer and Birmingham television reporter James Atkins from a man wielding a baseball bat: “One more swing and you’re dead.” The mob backed away. If not for Mann, Barbee would have died.

Commissioner L. B. Sullivan later stated that he hadn’t had enough information about the riders’ arrival. He claimed he didn’t know what had happened. He said that when he finally arrived he “just saw three men lying in the street.” Later, he claimed not to have sent the police because he didn’t want to draw a crowd.

However, Sullivan was a member of the White Citizens Council. He had stated, “We have no intention of standing guard for a bunch of trouble-makers coming into our city making trouble.” Following in Bull Connor’s footsteps, Sullivan kept Klan leader and former Montgomery reserve policeman Claude Henley updated and agreed to wait for at least half an hour before showing up after the riders’ arrival. Some Birmingham Klansmen had joined Henley and local KKK members. Despite calls for help, Sullivan kept his word to Henley.

A short time later, Alabama Attorney General MacDonald Gallion arrived at the station. As a bleeding Lewis regained consciousness and tried to stand, Gallion read to him Judge Walter B. Jones’s injunction against the riders, written the previous night as Patterson and Kennedy negotiated over the phone. The injunction forbade “entry into and travel within the state of Alabama and engaging in the so-called ‘Freedom Ride’ and other acts or conduct calculated to promote breaches of the peace.” When he noticed Zwerg, Gallion also read the injunction to his unconscious body.

Lewis spotted Barbee, and they tried to lift Zwerg to his feet. A policeman told them they were free to go, but finding transportation was up to them. Sullivan said that all the whites-only ambulances were “in the repair shop.” Lewis put Zwerg in the back of a whites-only cab. The driver grabbed his keys and left. A black taxi driver was willing to take Lewis and Barbee, but the police wouldn’t let him take Zwerg. The cabdriver dropped off Barbee at St. Jude’s Catholic Hospital in west Montgomery and took Lewis to a local black doctor who shaved and cleaned his injured head.

Floyd Mann realized that Zwerg would never be taken to a hospital by Montgomery police, so he and state patrolman Tommy Giles drove Zwerg to St. Jude’s. Zwerg briefly revived in the car. Upon hearing Mann’s and Giles’s Southern accents, Zwerg assumed he was going to be murdered. After they dropped him off, a nurse heard that a mob was approaching to lynch Zwerg. She sedated him so he would be unconscious in case they succeeded.

Zwerg faded in and out of consciousness for two days. He had cuts, bruises, fractured teeth, abdomen trauma, broken thumbs, a broken nose, a severe concussion, and three cracked vertebrae. He later joked that ambulances were only called in Montgomery after someone died.

Both Zwerg and Barbee, lying one floor below Zwerg in the Negro section of the hospital, swore they would continue the Freedom Rides. Zwerg declared, “Segregation must be stopped. It must be broken down. We’re going on to New Orleans no matter what. We’re dedicated to this. We’ll take hitting. We’ll take beating. We’re willing to accept death.”

An iconic photo of a bloodied Zwerg and Lewis appeared on the front pages of newspapers around the world. Afterwards, Zwerg couldn’t remember making the above statement that helped galvanize public support for the freedom riders’ cause.

He and other riders paid a steep personal price. Zwerg’s mother had a nervous breakdown, and his father suffered a heart attack. He stayed in the hospital until May 25, when the FBI drove him to the airport and his family minister took him home to Appleton, Wisconsin. Zwerg experienced pain for the rest of his life, but he and his parents physically recovered; their relationship took more time.

Barbee was permanently damaged. Never the same person afterwards, years later he killed himself by stepping in front of a bus.

Other riders had hidden in a nearby Presbyterian church or were shielded by the black community. Hermann and Wilbur called the police, who forced them to get on a train back to Nashville. A volunteer picked up Lewis from the doctor’s and drove him to the home of the Reverend Solomon Seay Sr. Lewis’s coat, shirt, and tie were stained with blood, but he was relieved to find $900 still in his pocket.

Reverend Seay had arrived at the station to find two students, one white and one black, lying in the street. He thought they were dead, but the riders had been taught to mimic convulsions so they would seem dead. He tried to collect some of the riders’ scattered possessions before returning home to welcome the others.

From left to right: Nashville Freedom Riders Bill Harbour, Lucretia Collins, Jim Zwerg, Catherine Burks, John Lewis, and Paul Brooks in Chicago in July 1961. (Courtesy of Bill Harbour)

The riders embraced one another and were introduced to members of the Montgomery Improvement Association. Gathering at Seay’s house gave the riders a renewed sense of determination. Nash wanted to harness this feeling of solidarity. She contacted Martin Luther King Jr. about getting the SCLC to help her plan a mass meeting in Montgomery.

The riders cheered when they heard that other activists were on their way. Jim Lawson, Diane Nash, Fred Shuttlesworth, James Farmer, and Hank Thomas were flying in from around the country. Farmer called in CORE members from New Orleans and Ella Baker sent SCLC members from Atlanta. To Robert Kennedy’s chagrin and the riders’ delight, Martin Luther King was on his way.

Riots Continue

The Sunshine Valley Boys sang on Montgomery’s WSFA-TV, “On a Greyhound bound for New Orleans was such a gang you have never seen: In rode the no-good ‘Freedom Riders’; just a bunch of trouble-making outsiders.” Nash, of course, denied that students caused the violence: “The people who committed violence are responsible for their own actions.”

The mob at the station grew. Some one thousand whites rioted on and off for the next two days. They threw suitcases and their contents in the air. People who appeared to be normal citizens in their daily lives danced around bonfires built to burn the freedom riders’ possessions, including books, notebooks, toothbrushes, deodorant, and suitcases.

Civil rights lawyer Clifford Durr and his wife Virginia watched from Clifford’s law office across the street. The white Durrs had been put under surveillance by the FBI and were shunned by their community for their progressive beliefs.

Virginia Durr sent college student Bob Zellner to find her friend Jessica “Decca” Mitford, a British author who was reporting for Esquire magazine. He passed by a sheet of plywood with a brick lodged halfway through it before wading into the crowd and spotting Mitford taking notes in the chaos. After alarming her by mentioning her name, Zellner explained who he was and brought her to safety.

The crowd attacked almost every African American in sight. Some soaked a black teenager in kerosene and set his clothes on fire while others jumped on his companion’s leg until it broke. Of those injured, Zwerg and Barbee were the most severely hurt, but five riders were hospitalized and more than twenty people received medical treatment.

At 11:30 a.m., Floyd Mann called in sixty-five highway patrolmen and mounted sheriff deputies. At 1 p.m., more police came, dispersed the crowd with teargas, and made a few arrests. Two of those arrested were liberal whites Anna and Fred Gach, who had intervened in the melee. Even though they were trying to help the riders, they were fined $300 for disorderly conduct.

By 4 p.m., the rioting had subsided, but the police’s relative inaction encouraged smaller groups of whites to continue demonstrating nearby. Court Street was empty, except for smoke, a few fires, broken glass, camera pieces, shoes, pieces of clothes, and puddles that looked like “glistening red jelly” but were actually blood.

Robert Kennedy was informed of the attack while he was at a baseball game. He called an emergency meeting and tried unsuccessfully to reach Governor John Patterson. Kennedy called the hospital where Seigenthaler was recovering from his fractured skull and broken ribs. Floyd Mann had made an emotional visit to Seigenthaler’s bedside, and Kennedy was relieved to talk to an apologetic Seigenthaler. Robert told him not to worry. He admitted that this conflict between states and federal rights seemed inevitable.

News reports and photographs from that day gave the United States worldwide negative publicity. With the approaching Cold War summit in Vienna, the president couldn’t ignore what had happened. At the same time, he knew that if he acted he would have political fallout in an area of the country that had supported him and his party. John Kennedy condemned all involved, including the riders, citizens, and local officials.

The Kennedy brothers were furious that Patterson, a political supporter, had allowed an attack on the riders and the attorney general’s representative. After midnight Saturday, Robert Kennedy called Patterson to tell him that there weren’t enough policemen to regulate the riots. Patterson blamed Kennedy for the problem and called the Freedom Riders “rabble rousers” and “mobsters.” He and Kennedy argued into the wee hours of Sunday morning. Finally, Kennedy said his brother, the president, had no choice but to send in federal marshals. He sent a publicized telegram to Patterson justifying the federal government’s actions asserting that the Kennedy administration’s involvement was a last resort necessary only because assurances that local law enforcement needed no help had been proven wrong.

Patterson considered the federal intrusion to be unconstitutional. He too worried about political backlash. The governor publicly said Alabama had to protect all human lives, “outside agitators” or not, but it was up to the state to determine how to do it.

Mass Meeting

Meanwhile, a mass meeting in support of the Freedom Riders had been called for 8 p.m. Sunday night at the First Baptist Church pastored by the Reverend Ralph Abernathy on North Ripley Street. Diane Nash and the SCLC’s Wyatt Tee Walker arrived Sunday morning. James Bevel and Jim Lawson came later that day. Martin Luther King Jr. canceled a talk in Chicago and flew to Atlanta, writing his speech during the plane ride.

Robert Kennedy knew that protecting King would send an unpopular message to the segregationist white South, but he nevertheless sent fifty federal marshals to escort King from the airport to the church and twelve marshals to escort Fred Shuttlesworth.

King greeted the battered riders in the basement library of the church. After helping King, Abernathy, and Walker plan the mass meeting, Shuttlesworth left to pick up James Farmer, who was flying in from Washington. On Shuttlesworth’s way to his car, he was assaulted with small stones and stink bombs. When Shuttlesworth returned later with Farmer, harassing whites rocked his car. By now, a large mob was gathered outside the church.

Shuttlesworth and Farmer managed to escape through the nearby Oakwood Cemetery. Circling back around, Shuttlesworth boldly marched directly into the mob, loudly ordering the rioters to make way. A terrified Farmer, who towered over the much smaller Shuttlesworth, followed in his wake. Farmer later described his surprise that he and Shuttlesworth both were not killed and attributed their safe passage through the mob to the mob’s astonishment at Shuttlesworth’s audacity.

They had an emotional reunion in the church basement.

By now, the church was filled with 1,500 blacks and a few whites, including Jessica Mitford and a white student, Peter Ackerburg, who would eventually join the Freedom Rides. Also present were reporters from three national television networks, state and local newspapers, the New York Times, Associated Press, and United Press International. Worried that the mob would try to break in and attack them, the church members tried to disguise the freedom riders as choir members, but Lewis had an unmistakable white x-shaped bandage across his head.

After dark, the mob outside doubled to about 3,000. Growing in size and aggression, the rioters waved Confederate flags, let out Rebel yells, and smashed car windows. The Durrs had loaned Jessica Mitford their car and advised her to park it several blocks away. Instead, she parked right in front and the mob saw a white woman entering the black church. Naturally, hers was one of the first to be overturned and set on fire. When its gas tank exploded, the congregation inside feared the blast was the start of an all-out attack.

Despite widespread publicity about the mass meeting, authorities were slow to arrive. When they did, marshals kept the rioters across the street, and Floyd Mann’s plainclothes patrolmen kept an eye on the situation.

The Reverend Solomon Seay Sr. opened the mass meeting with hymns. He described the inspiring courage of the freedom riders and introduced Diane Nash, sitting in the front row. Her presence was an emotional boost to many of the riders. A few other riders made statements, but since they were fugitives, Seay didn’t introduce them by name.

Reverend S. S. Seay Sr.

The crowd gave a standing ovation to Floyd Mann. One mother roused her child and told him to stand up and “thank a white public servant who had done his duty.” The atmosphere inside the church bespoke courage and confidence, not fear or panic. However, it was obvious that not everyone in the black community planned to rely on nonviolence. Some people carried pistols and knives.

Outside, the chaos escalated. One group of whites made it past the marshals and banged on the church door. By telephone, King asked Robert Kennedy for help. The marshals in Montgomery were undertrained and underequipped, and federal powers were reluctant to tread on “states’ rights,” but Kennedy assured him that 400 more federal marshals were on their way from nearby Maxwell Field.

Kennedy asked King to delay further Freedom Rides, and King relayed to Nash and Farmer the attorney general’s request for a “cooling-off period.” Nash vehemently disagreed, causing Farmer to loudly declare that African Americans had been cooling off for hundreds of years: “If we got any cooler, we’d be in a deep freeze.”

Outside, the reinforcement federal marshals arrived in military vehicles and postal trucks. A few were scared to leave their vehicles. With nightsticks and tear gas, they tried to restrain the mob, but angry whites continued to throw rocks and bricks at the church. One brick broke a stained glass window and hit an elderly parishioner. Nurses rushed to attend him and everyone dropped to the floor. Seay insisted that all children be taken to the basement. A few screamed. Tear gas wafted through the window, but the congregation continued to sing hymns.

Seay told everyone to stay calm and led in singing, “Love Lifted Me.” He stated, “I want to hear everybody sing and mean every word of it.” John Lewis and other riders joined the rest of the congregation in singing hymns and freedom songs such as “We Shall Overcome” and “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round.” The singing helped them take their minds off the mob outside and the stifling heat.

At one point, a few rioters pushed their way into the church. Marshals raced through the church basement and beat them back with clubs. By 10 p.m., the marshals reported that they were losing control.

Robert Kennedy asked the Pentagon to set up army units at Fort Benning, Georgia. He asked Mann for help, but Mann could do little without Patterson, who was listening in on the conversation. Mann asked for more marshals, but Maxwell had no more to send.

Gunshots were being randomly fired into nearby African American homes. The situation was so dire that King and Abernathy considered giving themselves up to the mob to save the congregation.

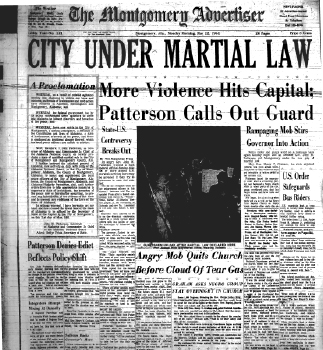

Finally, Governor Patterson declared martial law. Commissioner Sullivan, other city policemen, and 800 Alabama National Guardsmen replaced the federal marshals. Alabama officials declared that the state had everything under control and needed no more help from the federal government.

Many inside the church would have felt safer being protected by federal troops than by the segregationists who made up most of the Alabama National Guard. One reverend prayed, “Bless all those cowards standing outside. Bless that stupid governor of ours.” Wyatt Tee Walker, Ralph Abernathy, and James Farmer made statements. The meeting continued to fulfill Nash’s wish to foster a powerful sense of unity.

Headlines in the Montgomery Advertiser on the morning after rioters surrounded the mass meeting at the First Baptist Church.

Then King spoke. He noted that the law could not make him loved but it could keep him from being lynched. King urged nonviolent action against segregation in Alabama and stated, “Alabama will have to face the fact that we are determined to be free. Fear not, we’ve come too far to turn back.” He said, “the South proved it required the federal government to prevent it from plunging into a dark abyss of chaos.” He compared the barbarity in Alabama to that in Hilter’s Germany. King criticized Governor Patterson for creating “the atmosphere in which violence could thrive.” Shuttlesworth also called Patterson the “most guilty man in the state.”

As for Patterson, he called Attorney General Robert Kennedy back and yelled, “You’ve got what you want. You got yourself a fight,” foreshadowing the coming decade’s struggle among citizens, local authorities, and the federal government. Patterson called the riders communists and said that he couldn’t help protect King because he wouldn’t listen to the police. Kennedy responded that he wanted to personally hear “a general of the United States Army say he can’t protect Martin Luther King.” Knowing that Patterson’s reluctance to intervene had been politically motivated, Kennedy told him that the physical survival of the people in that church was more important than his and Patterson’s political survival. But Patterson heard this as yet another insult.

The Guardsmen had secured the area by midnight. Inside the church, people gathered sleeping children and moved towards the doors. But the doors were blocked and the troops outside faced them with bayonets. Guard officers told King that the state had taken over from the federal government and there was no available transportation; those in the church would have to make it through the mob to get home.

King responded that some of the people needed to leave. National Guard Adjutant General Henry Graham, an avowed segregationist, told King that it was too dangerous. King asked Graham to read to the congregants Patterson’s declaration of martial law, condemning “outside agitators” and federal authorities. The gatherers were now under protective custody.

King called Robert Kennedy again. By this time, the attorney general wanted to wash his hands of the situation. He told King and Shuttlesworth that they should thank the federal authorities for saving their lives.

Feeling trapped and angry, the large crowd spent the night inside the First Baptist Church, nervous about the Guard’s presence and concerned about what was happening outside.

The church was crowded and hot. Tear gas lingered. Though it was difficult to rest, many were grateful to be alive. Freedom Riders tried to cheer up the gatherers. Children slept in the basement, and the elderly rested on cushioned pews. Many lay on the floor.

Meanwhile, Justice Department officials negotiated with Graham to end the siege. One federal official observed that he felt strange in the Guard’s office. Confederate flags were everywhere (it was the centennial of the start of the Civil War), but he didn’t see a single American flag. Finally, the Kennedy representative threatened to send federal marshals back to the church. Only then did Graham send trucks and jeeps to the church.

By dawn, the mob had somewhat dispersed, and the National Guard began ferrying the people inside the church to their homes.

Regrouping

Newspapers the next day mentioned the night’s chaos, but their main focus was the cooperation among local, state, and federal law enforcement. Others, such as former governor Jim Folsom and the Alabama Press Association, were more critical of Patterson and the state. Montgomery Advertiser editor Grover Hall Jr. was unsympathetic to the riders, but he condemned Patterson’s hypocrisy.

The federal administration praised Mann, denied that they were about to send in troops, and played up the collaborative elements of the night. State and local officials said otherwise. They wanted federal marshals out of the city.

Federal powers agreed to work with local authorities and let the state charge riders. If evidence turned up against any rioters, federal authorities would make arrests. They did not. From the riders’ perspective, the federal government showed little interest in upholding their constitutional rights.

Robert and John Kennedy wanted to get the marshals out of Alabama. They had not performed well. The Kennedys knew they were on very tenuous political ground, likely to lose many Deep South Democrats, but Robert worried about how well the Alabama National Guard would protect riders.

The FBI was not much help. They had arrested the four Klansmen supposedly responsible for the Anniston bus burning, but Director J. Edgar Hoover insisted that the FBI’s purpose was to investigate, not to protect. FBI agents had recorded the Montgomery riot (with faulty equipment) without intervening. Hoover decided to investigate those he considered more dangerous than the Klan. According to him, these enemies included possible communist radical Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Violence against African Americans in Montgomery had continued until National Guardsmen were deployed, but the riders’ arrival was a turning point for the city. Ordinary white citizens in the community distanced themselves from the violence. As Solomon Seay Sr. said, the “better class of white people were beginning to get enough.” Businessman Winton M. “Red” Blount spoke out against police inaction and urged white business leaders to formally condemn the violence. Because many whites blamed the black students, A resolution was drawn up that criticized both sides. Eighty-seven out of almost one hundred who were asked signed the petition.

John Doar was also able to get U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. to issue a restraining order against Montgomery Klansmen. This gave hope to NAACP lawyers Fred Gray and Arthur Shores. They and several riders spent Monday in the federal building adjacent to the bus station to lift the previously issued state-court injunction against the riders.

John Lewis was nervous about testifying in court for the first time but hopeful because Judge Johnson had sided with Gray in Browder v. Gayle. Johnson asked Lewis why he joined the Freedom Rides. Lewis responded that he wanted to see the law carried out. Though Judge Johnson wondered if continuing the rides was intelligent, he considered Alabama Circuit Judge Walter Jones’s injunction “an unconstitutional infringement of federal law.”

Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.

John Lewis stayed at pharmacist Dr. Richard Harris’s house on South Jackson Street for the night. One of King’s former neighbors, Harris offered his house to SNCC, CORE, and SCLC members, who gathered there to discuss the future of the Freedom Rides. The younger generation—Diane Nash, John Lewis, and James Bevel—sat on the floor, while Ralph Abernathy, James Farmer, Wyatt Walker, James Lawson, and Dr. King sat on folding chairs.

Farmer later admitted that part of his reason for joining the riders was to reclaim the rides for CORE. Another motivation was to share the spotlight with King. Farmer offended many of the Nashville students when he referred to the rides as CORE’s.

The younger riders were also frustrated by King. Encouraged by SNCC advisor Ella Baker, Nash tried to convince King to join the next leg of the Freedom Rides into Mississippi. Wyatt Walker, Ralph Abernathy, and Montgomery SCLC staff member Bernard Lee argued that King was too valuable a leader to join them. Walker pointed out that King was on probation for a traffic citation in Georgia. If arrested, he could be thrown in jail for six months.

Younger riders stated that they too faced legal problems. Thinking of how difficult it was to gain Kennedy’s assistance, King reluctantly said no. When pressed, he replied, “I think I should choose the time and place of my Golgotha.” This statement came across as hubristic to some of the riders. After speaking privately with King, Walker announced that they would no longer discuss the matter. Students left the room, ridiculing King with the nickname, “De Lawd.” Paul Brooks was so upset, he contacted NAACP leader Robert Williams about the meeting. Williams telegrammed King and called him a phony.

The next day, on Tuesday May 23, CORE, SCLC, and SNCC called a press conference in Montgomery. Lewis, Abernathy, Farmer, and King made statements declaring that they would press on to Jackson whether the police would protect them or not. In an emotional statement, King said that no one wanted to be martyrs, but the riders were willing to be. He said that Jim Lawson would hold nonviolent training sessions for anyone who wanted to join. The unfortunate result of this conference was that it made King look like the mastermind behind the Freedom Rides.

When interviewed, James Lawson directed attention back to King. Lawson thought King had a legitimate reason not to go on the rides and felt it was both unwise and against nonviolent philosophy to pressure someone into joining them. Lawson’s workshops gave the riders strength for the upcoming days and inspired even those who had already gone through training.

Every Tennessee State student, except for Lucretia Collins, who had fulfilled her requirements, headed back to complete school. Tennessee Governor Buford Ellington had threatened to expel the riders. Diane Nash was prepared. By the time they left, she had already sent for reinforcements.

About thirty riders, including Hank Thomas, flew in and prepared to enter Mississippi. They were all apprehensive. NAACP members Roy Wilkins and Medgar Evers warned that Mississippi was too dangerous for the freedom riders. Robert Kennedy admired the riders’ fearlessness, but still wished that they would suspend the rides.

But the riders couldn’t stop their momentum. They got rid of anything that could be construed as a weapon or drug (such as hair pins or sleeping pills), learned about the legal impediments to their journey (though they were doing nothing illegal), and kept in mind that where they were going, they would have no rights.

The rides had attracted national attention when the Nashville students restarted the rides, but now this strategic plan was becoming an organic entity. Rider Jim Davis said that words Zwerg spoke from his bed moved him to catch a bus to Montgomery. People of all ages, religions, and backgrounds traveled across the country to join the rides. Members from CORE, SNCC, SCLC, and NCLC established the Freedom Ride Coordinating Committee in Atlanta to organize the riders.

John Kennedy told Robert Kennedy to “stop them.” John Patterson asked the president to send the agitators home. Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett praised Patterson’s resistance and repeated Patterson’s request. The American Nazi Party sponsored a “hate bus” from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. Through it all, the riders would not be moved.