1

Why the Freedom Rides?

The objective of the 1961 Freedom Rides was to travel across the South and integrate transportation facilities. Whites and blacks would ride together and deliberately use either “whites-only” or “colored” facilities, regardless of race. The goal was simple. Its execution and reception was not. Violence as well as subtler forms of discouragement such as bureaucratic opposition and internal conflicts awaited the riders.

The riders’ arrival in Alabama on May 14, 1961, and in Montgomery on May 20, 1961, were the key moments in the journey. These were turning points for the Freedom Rides, for the state of Alabama, the cities of Anniston, Birmingham, and Montgomery, and the civil rights movement.

Yet the rides themselves were built on a series of decisions and acts that had emerged over the past century.

In 1961, the United States was embroiled in the Cold War. America projected itself as a beacon of democracy against the growing shadow of the Soviet Union. In this international ideological struggle, the United States saw itself as representing hope, and the Soviet Union as standing for oppression. But within America’s own borders, a centuries-long conflict between freedom and oppression had never really ended.

The year 1961 was the centennial anniversary of the start of the Civil War, which was fought over issues which lingered for years after the armed conflict concluded. As a result of the Civil War, slavery was abolished, the South remained part of the United States, and, during Reconstruction, African Americans were granted equal rights. But in the following years, Northern whites made a kind of reconciliation with Southern whites that involved eroding the freedoms that African Americans had gained. As Southern whites continued to mourn their loss and to resent federal encroachment, Southern blacks were pushed to the margins of society in law and custom.

Segregation ordinances and rules came to be called “Jim Crow” laws. The term may have been derived from “Jump Jim Crow,” a blackface song and dance common in minstrel shows of the nineteenth century. Jim Crow laws segregated the races and allowed local rules and customs to override federal protections extended to blacks after the Civil War. Discrimination against African Americans was not limited to the South, but only in the South was segregation widely and legally enforced.

From Plessy v. Ferguson to Irene Morgan v. Virginia

Transportation in the South, like almost everything else, was segregated based on the concept of white supremacy. In practice, this meant that blacks were always relegated to second-class status or treatment or were barred altogether from enjoying goods, services, privileges, and rights available to whites. The Freedom Riders of 1947 and 1961 were following in a long tradition of protest against these injustices.

Prominent nineteenth-century black leaders like Frederick Douglass had protested segregated train seating. Sojourner Truth once got a conductor fired for striking her when she refused to move to a second-class seat. In the 1880s, following enactment of Louisiana’s Separate Car Act, the biracial Citizens’ Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law set the earliest precedent for the Freedom Rides of the next century.

On June 7, 1882, Homer Plessy, an “octoroon” (one-eighth African), was arrested on a train when he remained seated in the whites-only section. In a state court trial, the ruling was that states had the right to regulate transit within their borders. Citizens’ Committee’s attorney Albion Tourgee appealed to federal courts and argued that Plessy’s Fourteenth Amendment rights had been violated. On May 18, 1896, the United States Supreme Court ruled against Plessy. Justice Henry Billings Brown wrote the majority opinion that separate but equal facilities did not contradict equal rights as outlined in the Fourteenth Amendment.

In a solo dissent, Justice John Harlan stated, “Our Constitution is color-blind ... In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” He correctly predicted that this decision would inspire “brutal and irritating” aggressions against African American rights and encourage states “to defeat the beneficent purposes which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments of the Constitution.” Harlan foresaw that the Plessy doctrine of “separate but equal” would be applied throughout the South to schools, hospitals, parks, and every public service imaginable.

The legal issue of segregated transportation was revisited half a century later when Virginia authorities arrested factory worker Irene Morgan for not giving up her seat on a bus. A deputy grabbed her. Recovering from a miscarriage, she kicked him “where it would hurt a man the most.”

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) appealed Morgan’s arrest and conviction. Happily, the United States was in a different place in 1946—after two world wars in which black soldiers had fought for the U.S.—than it was when Homer Plessy was arrested in 1882. This time, the Supreme Court declared segregated seating on interstate transportation to be unconstitutional.

Truman Executive Order Desegregates the Military

In 1947, President Harry Truman’s Committee on Civil Rights recommended ending discrimination in the military. Truman, who was the first president to address an NAACP convention, took the suggestion to heart. He proposed a series of civil rights acts, including the desegregation of the military. Horrified by stories of lynchings, he included an antilynching law. Fellow Democrats, or “Dixiecrats,” as Southern Democrats were called, opposed his plans. On the other hand, labor leader A. Philip Randolph warned that African Americans would boycott the military if it weren’t desegregated. Truman was also struggling with the beginnings of the Cold War.

Truman’s solution was to back away from his legislation and instead issue Executive Order 9981, which expanded on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fair Employment Act. Truman’s order directly ended segregation in the military: “It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.” Truman’s bold move towards equality stunned both supporters and opponents.

The city of Montgomery was particularly piqued by this order. Its two Air Force bases, Maxwell and Gunter, provided the city with tens of millions of federal dollars. Truman’s order was a reminder that Montgomery had lost its standing since the Civil War and was now dependent on federal money for support.

But the military had to comply, even within the South.

The 1947 Journey of Reconciliation

The Irene Morgan decision was largely ignored in the South. Transportation officials used technicalities to maintain segregation by pointing to private “company rules” instead of state law.

Some African Americans protested, with mixed results. World War II veteran Wilson Head rode at the front of a bus from Atlanta to Washington. Black historian John Hope Franklin accidentally sat in the wrong seat after donating blood to his dying veteran brother. When told to move, Franklin refused, and other blacks on the bus encouraged him. Both he and Head braved intimidation, but neither were arrested or attacked.

Veteran Isaac Woodard suffered a more horrific fate on a trip in South Carolina. A bus driver swore at him when he asked to use the restroom at a stop, and Woodard swore back. At a subsequent stop, the driver complained to police, who attacked Woodard with a billy club. After fighting in the Pacific for more than a year, Woodard had returned home only to be beaten so severely that he lost his sight. In spite of army doctors’ testimony and an FBI investigation, an all-white jury in Columbia, South Carolina, acquitted the police chief involved.

Meanwhile, President Harry Truman’s creation of a Commission on Civil Rights had given activists hope. The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), founded by Christian pacifists in 1914, favored direct action. Inspired by Gandhi’s nonviolent struggles against colonialism, FOR’s Racial-Industrial Department secretaries Bayard Rustin and George Houser contemplated an interracial bus ride.

Neither had much experience in the South. Born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Rustin had attended school in Ohio—where he was expelled for his homosexuality and for challenging authority—and Pennsylvania before moving to Harlem during the Great Depression.

Inspired by his Quaker grandmother, Rustin turned his talents (he was a brilliant student, singer, and athlete) towards promoting communism and eventually socialism. He thought nonviolence was the solution to the black struggle due to African Americans’ adaptability, endurance, and faith. Rustin protested injustices during his three years in prison for draft evasion, and when released he traveled across the United States for FOR practicing civil disobedience and preaching pacifism. He was arrested and beaten for refusing to move to the back of a bus in Nashville.

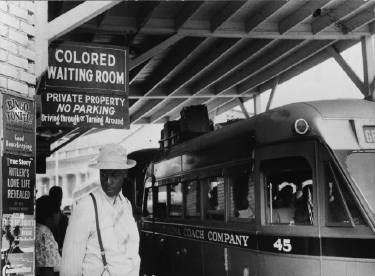

A Library of Congress photo depicting a typical segregated bus depot waiting room in the Jim Crow era.

In 1942, Rustin, Houser, Homer Jack, and James Farmer founded the interracial Chicago Committee of Racial Equality, later renamed Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Farmer was born to intellectual, well-educated parents in Marshall, Texas. He watched his multilingual father defer to whites and experienced Southern segregation first hand when he had difficulties finding food, shelter, and restrooms during his travels.

At the Howard University School of Theology, Farmer was introduced to Gandhianism. Instead of becoming a Methodist minister, he contributed his powerful elocution skills to FOR. Farmer loved the idea of the proposed ride but was unable to participate. (He ended up leaving FOR and CORE, but he would return to CORE as its national director in time to spark the Freedom Rides of 1961.)

Rustin and Houser hoped that their FOR-sponsored ride, which they named the Journey of Reconciliation, would expose CORE to the South, increasing funds and improving knowledge about the national civil rights movement. They listened to warnings from Southern contacts to avoid the deep South. The NAACP did not support the idea. Attorney Thurgood Marshall, who eventually became the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court, thought the idea was well-meaning but dangerous. Rustin argued that violence was inevitable, but using nonviolence would keep bloodshed to a minimum. He and Houser quietly scoped out the journey, researching Jim Crow laws and conferring with activists about housing. This step helped convince NAACP, but tensions remained. CORE sought to enforce NAACP’s legal groundwork through direct action, but NAACP’s focus remained on legal means.

Despite objections by women who had helped plan the trip, CORE decided a mixed-sex group would exacerbate problems. They had difficulty finding eight white men and eight black men with enough time and dedication to take the trip. Ultimately, fewer than half finished the whole journey, and they had to draw on CORE activists to complete the group. CORE members joining the trip included Rustin, Houser, founder and Unitarian minister Homer Jack, biologist Worth Randle, law student Andrew Johnson, pacifist lecturer Wallace Nelson, social worker Nathan Wright, and chief publicist James Peck.

James Peck would become the only person to take part in both the Journey of Reconciliation and the 1961 Freedom Rides. A radical from his youth, he had brought a black date to his Harvard freshman dance, offending both his wealthy Manhattan family and the school. Alienated for his political beliefs and background in Judaism (his family had converted to Episcopalianism), Peck dropped out and moved to Paris. When he returned to the United States, he founded the National Maritime Union and befriended American Civil Liberties Union founder Roger Baldwin. Before joining CORE, Peck went to prison for draft evasion (one of six riders to have been conscientious objectors). There he desegregated the prison mess hall by leading a strike.

Also traveling on the Journey were FOR Methodist ministers Louis Adams and Ernest Bromley from North Carolina, jazz musician Dennis Banks from Chicago, Joseph Felmet with the Southern Workers Defense League from Asheville, North Carolina, civil rights attorney Conrad Lynn from New York City, peace activist Igal Roodenko from upstate New York, North Carolina A&T College agronomy instructor Eugene Stanley from Greensboro, North Carolina, and New York Council for a Permanent FEPC member William Worthy.

None of the young travelers had practiced direct action in the South. Rustin and Houser handed out pamphlets stating that they were establishing U.S. law. The group role-played for two days. Instructions were to remain calm, to not leave the bus unless arrested, to go peacefully if taken away, and to raise bail or have an organization pay.

On April 9, 1947, the riders and two African American journalists set off from Washington, D.C., Greyhound and Trailways stations. They made it to Richmond, Virginia, without difficulty. A few fellow passengers even sat outside their regulated seats. Leigh Avenue Baptist Church welcomed the riders, but middle-class students at the all-black Virginia Union College hardly acknowledged racial discrimination in transportation.

On the trip to Petersburg, a passenger warned that “the farther South you go, the crazier [bus drivers] get.” The Greyhound driver called the police when Rustin didn’t switch seats after being asked, but the police made no arrests. Most black passengers seemed to approve. The Trailways bus driver told Conrad Lynn to move and didn’t listen to his invocation of the Morgan ruling. The driver said he followed his employers’ rules about segregation, not the Supreme Court’s. Others on the bus, black and white, didn’t support Lynn, and a policeman hauled him away. Lynn was released on a $25 bond and soon joined the others at St. Augustine’s College in Raleigh.

In Durham, North Carolina, a Trailways superintendent told the group that while Greyhound might be letting them ride, Trailways was not. Rustin, Peck, and Andrew Johnson were arrested, and local black leaders encouraged others to shun the troublemakers. However, a rally for the riders gained support, and the NAACP secured their release.

Chapel Hill appeared to be a racially progressive college town. The white Reverend Charles M. Jones housed them, but when boarding a Trailways bus to Greensboro, Joe Felmet, Igal Roodenko, Johnson, Peck, and Rustin were arrested. The driver passed out cards absolving the company from liability. The cards didn’t particularly impress other passengers.

After the riders posted bail, a group of cab drivers surrounded Peck. One man struck Peck but walked away, confused, when Peck didn’t retaliate. The group almost attacked a white minister and a black teacher who stepped in before realizing that they were from North Carolina.

Carrying sticks and rocks, the taxi drivers followed Jones and the riders to his house. They left without incident, but that night Jones received a phone call threatening to burn down his house. Jones had three university students drive the riders and made sure the police accompanied them to the county line. In the following days, staunch segregationists menaced Jones and other perceived liberals. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill President Frank Graham put an end to the assaults by insisting on police action.

The Shiloh Baptist Church in Greensboro embraced them as it would eventually embrace the 1961 Freedom Riders. On the leg to Asheville, where riders would stay with Joe Felmet’s parents, a white South Carolinian said the riders would have been removed or killed in his state, but one bus driver accepted the Morgan explanation and told a frustrated soldier to “kill the bastards up in Washington” instead of rider Wallace Nelson.

In Asheville, Peck and Dennis Banks were arrested. In jail, Peck was threatened by white inmates, while Banks was regarded by a few of the black prisoners as a hero. Their NAACP-affiliated attorney Curtiss Todd became the first black lawyer to practice in an Asheville courtroom, where even Bibles were marked “colored” and “white.” The judge hadn’t heard of the Morgan decision and sentenced Peck and Banks to thirty days on the road gang. Todd paid the $800 bond, and they were released.

The group embarked on their first nighttime ride in Knoxville, Tennessee. Chicago activist Homer Jack found the Southern night foreboding but concluded that their biggest enemies were fear and apathy. They caught the train in Nashville, where the conductor thought Nathan Wright was Jack’s prisoner. When set straight, he told them to go to the “Jim Crow coach” and claimed that in Alabama they’d be thrown out the window. They stayed put, and the conductor remained flabbergasted.

After a few more arrests and much more confusion from law enforcers, the Journey of Reconciliation came to an end in Washington on April 23. Arrests were cleared or dropped everywhere except in Chapel Hill, where Rustin, Johnson, Roodenko, and Felmet were sentenced to thirty days on the road gang. The NAACP refused to appeal to the Supreme Court. They claimed to have lost the ticket stubs proving that the defendants were interstate travelers, but NAACP’s budget was thin, and its focus was on legal battles over issues such as school desegregation.

Rustin, Felmet, and Roodenko decided to prove their commitment by accepting the sentences. They were released after twenty-two days, with their sentences shortened by a week for “good behavior.” Rustin later described in a serialized memoir the prison camps’ harsh conditions and the guards’ hatred toward “Yankees.”

The black press said the journey raised awareness among Southerners about solutions to segregation. Riders assessed that the trip informed passengers and law-enforcement officers, and it proved that direct action could lead to enforcement of the Morgan decision.

CORE considered the journey a success and expected more interracial rides, but there were none. In the 1950s, when the country froze under McCarthyism, FOR dwindled and eventually withdrew support from a floundering CORE. The NAACP refused to fund another proposed Ride for Freedom.

The 1961 Freedom Rides would have a very different effect from the largely forgotten Journey of Reconciliation.