2

Henderson Harbor

UNITED STATES

I’d pull the troops and carriers out of Afghanistan and napalm the [cormorant] rookeries. For years, they’ve done fighter runs over the Great Lakes to practice bombing. Why not the real thing?

MARK CLYMER,

sport fisherman, 2002

Captain Ron Ditch has spent the last twenty-five years leading the fight in his small community of Henderson Harbor, New York, against the local population of cormorants. He founded an organization called “Concerned Citizens for Cormorant Control.” To build his case, he amassed reams of biological and policy research on the birds. He and a local television producer, who is also a fisherman, created a short film to demonstrate the need for managing the local cormorants. His most significant act—and he will tell you “achievement”—was when he organized a small group of fellow fishermen to go out and kill thousands of cormorants on the night of July 27, 1998.

Ditch and a few other men, including his two sons, had already gone out a couple of times in previous years to kill cormorants on Little Galloo Island in eastern Lake Ontario.

“But we were losing,” he tells me. “So I gathered a few boys together and told them what I wanted to do. We knew it was illegal, but we had to send a loud message. I told them it’s a fifty-fifty chance we were going to get caught. But we either lose our business or take the chance. I asked if they were in or if they were out. Five said they were in.”1

Thanks to a good idea from his wife, they went out on a night when there were fireworks over in Oswego. As Ditch tells it, they took four boats and powered the ten or so nautical miles over to the island. It’s a flat island with a rocky edge. Only a few dead trees remain, which are close to the water. The cormorants like to nest in the limbs. A couple of men from the deck of one boat shot as many as they could out of these trees. Once they started shooting, though, the adult cormorants flew away. Tens of thousands of gulls flew overhead and shrieked and cawed.

Little Galloo Island is not an easy place to tie up, but it wasn’t that windy that night, and it was clear enough so they could see enough of what they were doing. Anchoring to keep their boats off the rocks, the men stepped ashore. With the thousands of shrieking gulls still overhead, the men shot at any adult cormorants that had not flown away. The cormorants gathered in the water just off the island, near enough so one of the fishermen still in a boat could pick more of them off. Ron Ditch is a duck and deer hunter, as are the other men. They are good shots.

By this midsummer night nearly all the cormorant eggs had hatched. Most of the chicks were old enough to walk around. Those that had learned to fly had tried to escape to the water with the adults. There were also thousands of chicks that could walk but could not yet fly. These fledglings huddled into what biologists refer to as nursery groups or “crèches.” Ron Ditch and his men walked over to these groups and opened fire. The young birds’ high-pitched peeping was impossible to hear over the noise of the gunfire and the gulls.

“We went out and killed about twenty thousand cormorants,” Ditch tells me. “And the feds got all upset about it. They fined us $100,000. But it did get their attention and got the attention of all of North America. Had we not done that I don’t think the situation ever would’ve changed. We were told that the federal Fish and Wildlife Service’s attitude towards the cormorant situation would never change. In other words, the tree-huggers and the bunny-huggers didn’t want you to do anything as far as birds were concerned even though they were destroying a way of life and a fishery and affecting millions and millions of dollars in a fishery that was dying because of the birds. So, we did. We took the law into our own hands.”

“Did you say you killed twenty thousand birds?”

“Yes, they prosecuted us for two thousand, but they had no idea what was going on. I wish we got another twenty thousand.”

Ditch adds: “I guess I kind of became a local hero.”

The government did indeed take action after this incident, both on the state and federal levels. State wildlife managers have since slowly reduced the size of the cormorant colony.

|

Red-faced Cormorant (P. urile)

Pelagic Cormorant (P. pelagicus)

Brandt’s Cormorant (P. penicillatus)

Neotropic Cormorant (P. brasilianus)

Great Cormorant (P. carbo) |

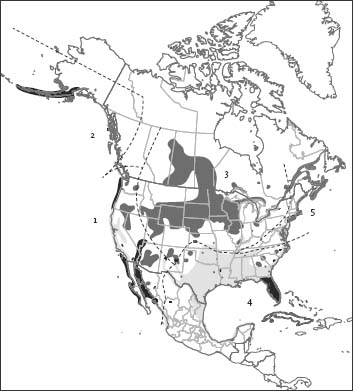

Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus) Six species of cormorants live and breed in North America. In the map of the double-crested cormorant’s range (above), dark gray represents breeding grounds, light gray wintering grounds, and black both breeding and wintering grounds. In maps of the ranges of the other five species (left), dark gray represents the extent of their combined breeding and wintering grounds. In North America, the double-crested cormorant can arguably be divided into five populations: 1) Pacific Coast, 2) Alaska, 3) Interior, 4) Southern, and 5) Atlantic. For management purposes, USFWS identifies four groups, combining the Pacific Coast and Alaska populations. |

Over a decade later, I meet Ron Ditch at his house once again. He says to me: “I guess everything has come out pretty good, huh?”

Six species of cormorants live in North America.2 (See map.) The double-crested cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus), the object of Ron Ditch’s ire, is the most prevalent and the only one found appreciably inland. Double-crested cormorants nest in the spring in forty-three states, in all of the ten Canadian provinces, as well as Cuba, Mexico, and the Bahamas.3 During migrations or winter roosting they spend time in every state except Hawaii. They travel as far north as Alaska and Labrador and as far south as the Yucatán Peninsula.4

The double-crested cormorant gets its common name from two tufts of feathers on its head. The species name auritus—Latin for “eared”—comes from these crests. To the human eye the crests look mostly comic. When viewed from the front with binoculars, the bird looks like a mad professor. The crests are only visible for several weeks a year when the cormorant is attracting mates, coinciding with an increased gloss and sharpness to all the bird’s colors. The bare skin under the double-crested cormorant’s beak is bright orange. This is called its gular pouch, a much smaller version of the same on its pelican cousin. Like Mr. Yamashita’s Japanese cormorants, the double-crested cormorants’ eyes are emerald green. When attracting the opposite sex, double-crested cormorants have a vivid cobalt-blue lining inside their mouth.

Ron Ditch and other charter captains and sport fishermen throughout the Great Lakes think there are too many cormorants in their area and across the continent. How many cormorants are actually in the water catching fish and how many there should be is at the base of almost every debate about these birds. Local, national, or international management discussions inevitably turn to numbers. So if you’re not an ornithologist or a wildlife biologist, let me give you some background before we get into the population figures.

First of all, it’s hard to count birds. They fly around when you approach. Cormorants migrate and spend months in different parts of the continent, sometimes in several different regions. Cormorants may adjust from year to year where they nest, based on food availability and human disturbance. In different parts of the country and the world, if counting is done from afar or above, one species of cormorant might look like another cormorant species that might overlap the same range, or they might look like other birds, such as anhingas or loons.

Official bird counts usually refer to “breeding pairs,” which means the number of active-looking nests in a breeding colony. All agree this counting of nests is relatively simple, accurate, and can be normalized across different areas and over the years. Biologists and managers do not all agree, however, on how exactly a given nest translates to how many adult cormorants there are at a colony by the end of the summer when all the chicks of that breeding season are full grown. Sure, there are two breeding adults. But how many of their chicks will survive? Double-crested cormorants, similar to most of the other cormorant species, can lay from one to seven eggs. A clutch of three or four is most common for this species.5 The survivorship of these eggs into the first year is hard to predict, based on all manner of environmental and genetic factors, especially the age and experience of the individual parents.6 Also at colonies are nonbreeding adults who are too young or who don’t mate for one reason or another. Typical of the other cormorants around the world, double-crested start breeding most commonly toward the end of their third year.7 They can then continue to live several years in the wild afterward, breeding each year.

The average life expectancy of these cormorants in the wild might be about six years old.8 Mr. Yamashita’s thirty-five-year-old Japanese cormorant couldn’t survive out on his own at his age, of course, but a man in 1984 did find a dead wild cormorant at Inks Lake, Texas, which had been banded and registered in Saskatchewan more than seventeen years earlier. There surely are cormorants still older out there.9 There was a cormorant that was shot in the British Isles that had lived to be more than thirty years old in the wild.10

With all of this factored in—clutch size, age of breeding, life expectancy, and all sorts of threats to survival and reproduction—conservative estimates that compile nest counts multiply by three to get to the total number of individual cormorants.11 For example, ten nests or ten breeding pairs at a colony roughly means thirty individual cormorants by the end of a summer.

Thus bird population numbers are estimates. The good scientists and wildlife biologists are careful to reveal their level of confidence, but their numbers are often misinterpreted, mishandled, and easily confused by journalists and members of the public.

I once worked as a volunteer for the Audubon Society on an island in Maine. Despite the diligence of our supervisors and the earnestness of me and my partner, I can assure you that we did a poor and inaccurate job counting egret and ibis chicks. Our numbers still went into official reports. Generally this is OK. What biologists examine is relative change given a consistent methodology over a significant amount of time, allowing for the squish of human error due to volunteers like me or due to circumstances like torrential downpours, for example, on the one day that year allotted to count the nests.

So with this primer, know that the best figures estimate at least one to two million double-crested cormorants in North America today, living in over 850 colonies.12 This most recent total is from nest counts around 1997, the year before Ron Ditch hit his local island. (For reference, there are about one million herring gulls on the North American East Coast, and there are about five million Canada geese across North America.13)

Now to put the double-crested cormorant in perspective within the cormorant family, you should know that this is not the most populous cormorant species around the world. Nor is Ron Ditch’s Henderson Harbor the only place on earth or the only time in history when fishermen went out one night to kill a bunch of cormorants. North America and its double-crested cormorants do represent, however, more so than anywhere else in the world and during any time in history, the most significant Human v. Cormorant conflict in terms of geographical area, monetary investment, the sheer numbers of people involved, the diversity of groups with a stake in the management, and the different types of industries, organizations, and community groups who care where these birds are and exactly how many are paddling about. Throughout the continent thousands of American and Canadian citizens are so pissed off at cormorants that they either want to blast these birds out of the air with a legal blessing or they want their tax money to pay to have someone else do it. People like Ron Ditch and his wife hate cormorants because they believe the birds eat too many of a particular kind of fish. Other citizens are outraged about cormorants nesting and roosting in places where the birds’ guano kills the trees and foliage, altering an island or a shoreline’s landscape. People also worry that cormorants endanger the prosperity of other native fauna or flora that is more rare or more preferred. A few others are afraid of the diseases and parasites that cormorants can or purportedly carry.

Taxonomists divide the double-crested cormorants into five subspecies, based mostly on physical characteristics.14 Federal managers, more the concern of Ron Ditch, divide the North American cormorants into four populations based on where they nest and migrate. These four groups are the Interior, Southern, Atlantic, and Pacific Coast–Alaska populations.15

In this book, between migrations around the world to places such as Gifu City and Cape Town, we will periodically return to North America. We’ll travel to all four of the double-crested population areas. This enables a broad case study of one particular cormorant species and an examination of situations in which (1) sport fishermen want to kill cormorants, (2) commercial fishermen and local conservationists want to kill cormorants, (3) aquaculture fishermen want to kill cormorants, and (4) wildlife biologists charged with protecting endangered fish want to at least move cormorants someplace else—if not kill a few hundred here and there.

Ron Ditch’s wife, Ora, says it took several months before authorities identified her husband and the other men who shot the cormorants on Little Galloo Island.

“It was a scary, emotional time,” she tells me. “Everyone was whispering to each other. It was all over the news.”

Mrs. Ditch points outside her window over to a dock. “Right over there was a van with antennae sticking all over. They were listening to everything we said. Men with too many creases in their shirts were coming up to our place asking for a brochure to go out and fish with Ron. But you could tell they weren’t fishermen.”

As the Ditches had hoped, the event went national. Newspapers and television from Alaska to Florida carried the story. The New York Times ran it on the front page with a photograph of bloodied dead birds. This was the article I first read over a bowl of Cheerios with my housemate Munro. A spokesman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared at the time that the act on Little Galloo was the most significant mass killing of a federally protected animal species in at least twenty years.16

“They caught us eventually,” Ditch says. “It’s my understanding that two young good-looking women were undercover at the bar. Feds. I don’t know how stupid you have to be, because there haven’t been two young good-looking women at our one bar—in January, the off-season, a snowy night—since the start of this town.”

Ora Ditch scoffs.

“Well, two of the boys,” Ron continues. “I’m not naming names. They had too much to drink, so I heard. And they spilled the beans.”

Throughout the Great Lakes and on the inland bodies of fresh water in the bordering provinces and states, sport fishermen catch a large variety of fish species. Anglers cast lines from the shore, they push off in their own small boats, and they pay to go out on larger boats with charter captains who know the area and who will, if you want, bait your lines, teach you how to reel in the fish, and even fillet your fish for you. Though steadily trending downward, since the 1970s over eight million fishing licenses have been sold annually on the American side of the Great Lakes.17 Sport fishermen visit the local towns and buy fuel, eat at restaurants, stay at hotels, and buy these licenses. They buy bait, fishing gear, and boating equipment. Some love an area so much that they buy lakeside property. Over the last thirty years this has represented thousands of jobs and regularly brought in tens of millions of dollars to various communities. According to one study, this income peaked in 1988 at about $100 million in “angler expenditures” for the U.S. communities bordering all the Great Lakes.18 Henderson Harbor and the nearby towns around eastern Lake Ontario have consistently been one of the more popular of Lake Ontario fishing destinations.

The bulk of the catch for Ron Ditch and the forty or so other licensed Henderson Harbor fishermen who run charters is salmon, trout, bass, and walleye. Ron Ditch’s favorite fish to catch is smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieui), also known locally as black bass. For him this is the prize of Henderson Harbor. He runs some charters to target only these fish. Smallmouth bass is a good fighter, and it tastes excellent.

“This part of Lake Ontario was in years past the number one spot in all of the Americas for smallmouth bass,” Ditch says. “It was great fishing here in better days. Eddie Bauer came up to fish for bass. And I could go on with a whole bunch of other people who over the years have come up just to catch bass.”

Henderson Harbor is a good place to cast your lines because it is in a long protected inlet in which you can still motor out even if it’s rough on Lake Ontario. A few distant beaches are good places to have picnics and cook up your catch. Ron’s father, Ruddy Ditch (pronounced Rudy), was a charter fisherman in Henderson Harbor, too. Ruddy began as a charter captain in 1934, then with his son Ron started “Ruddy’s Fishing Camp” in the 1950s. For over half a century now, families have come up to stay in their waterfront cottage or one of their rustic apartments. Visitors grill their fish outside at night beside the dock and watch the sun go down.

Ron Ditch is now in his eighties. He still runs Ruddy’s Fishing Camp with Ora. He still takes people out fishing on his own boat. One of their sons helps run the business, too. Ron and Ora have four grandsons, one of whom is already, as Ron says, “a fishing fool—he’s been fishing since he could crawl in the boat.”

Ron Ditch has held a U.S. Coast Guard captain’s license for over sixty years. “I would have to guess that I am probably the most experienced and oldest continuous captain on Lake Ontario in history,” he says. “That’s not to pat myself on the back. I don’t know if that makes me smarter or dumber.”

Part of the attraction to Henderson Harbor is that it is a hamlet. There’s no town green or any central area. It is just a serene, gorgeous, lakeside community. Within Henderson Harbor’s boundaries and in the neighboring area, the recreational fishing industry these days employs perhaps a few hundred people directly, although few if any can live on the seasonal income all year round.19

Ron Ditch passes by Little Galloo Island almost every time he takes his guests out to fish. He sees Little Galloo when he casts lines at Calf Island Shoal, one of his favorite fishing spots for bass. Cormorants sometimes nest on Calf Island and regularly roost there. Although tens of thousands of gulls live on Little Galloo, they are barely visible from the waterline because the cormorants nest primarily on the outer rim of the island. At the height of the colony’s cormorant population, all you could see from the water were cormorants. Ditch’s charter fishing season is generally from late April to September, which coincides almost exactly with the arrival of the cormorants, their nesting and raising of chicks, and then the flock’s departure to migrate south.

Cormorants were first known on record on Little Galloo Island in 1974, when wildlife biologists counted twenty-two cormorant nests. A decade later there were over 1,400 active nests.20 Residents of Henderson Harbor, particularly those out on the water often, watched as this local cormorant population continued to grow rapidly in the 1980s and into the 1990s. Ron Ditch and his fellow fishermen complained to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation—who had already been monitoring the situation and had begun to count birds annually. The state biologists kept cormorants from nesting on the other potential colony sites on Eastern Lake Ontario, within American waters.21 In 1992 the state wildlife biologists counted 5,443 pairs of breeding cormorants spending the summer on Little Galloo. In 1996 the Little Galloo colony peaked at 8,410 pairs of cormorants, thus over 25,000 total birds.22 At the time, this was the largest single colony of this cormorant species in the United States and almost certainly all of North America, which means in the world.23 In addition, almost 2,500 more cormorant pairs were living on five colonies on the Canadian side of this eastern basin of Lake Ontario—a short flight away.24

Over the years, Ron Ditch watched these birds gulp down some mighty large fish right in front of his eyes. He saw the shape of fish inside a cormorant’s neck as it swallowed its prey. He watched thousands of cormorants swarm on a school of fingerling trout released to supplement lake stocks. Ditch’s front porch looks out onto a boat channel in which he has seen cormorants dive and eat bass the size of his shoe.

Meanwhile, state biologists were compiling a report, published after the raid on Little Galloo, which suggested the smallmouth bass population in eastern Lake Ontario had indeed decreased to the lowest level it had been in two decades.25 This confirmed what Ron Ditch had been complaining about. The scientists published what they found to be “convincing evidence” pinning the decrease in schools of smallmouth bass and yellow perch to the growing number of cormorants in this part of the lake.26

“I tried for thirteen years to get the government to listen to us because the cormorant is not a native bird to this part of the world,” Ditch tells me. “You see when they did away with DDT it allowed these birds to propagate in such numbers that they got way, way, way out of balance. We had at one time about 150,000 cormorants on this side of Lake Ontario. And those birds eat a pound of fish a day.”27

To help pay for the total of $100,000 in fines for which Ron Ditch and his men were collectively slapped, members of the Henderson Harbor community held pasta dinners and other fund-raisers. The fishermen began calling themselves “The Ten.” This was the number of people prosecuted for the cormorant slaughter in 1998 and for previous runs out to the island. They received donations in the mail from all over the country. Ron and Ora Ditch had anti-cormorant posters and buttons made up. They made flags, which a few people flew from their boats. One man stapled the flag beside his garage door with a long black feather. “I support cormorant control,” the flag reads, featuring a circle and a red slash over an illustration of a cormorant. I can tell you that the feather stayed stapled to the flag for at least three years, and, though yellowed and brittle, the anti-cormorant flag was still stapled beside that garage the most recent time I was up in Henderson Harbor, which was almost fifteen years after “the shoot,” as Ditch calls it.

Various marinas and fishing supply shops in town sold the anti-cormorant gear that Ditch made to raise money for their fines. You could buy white hats with red circle-slashes across cormorant silhouettes. The hats said: “Concerned Citizens for Cormorant Control” or “I support Cormorant Control.” Another hat style had “Little Galloo Island Shootout” stitched on the front. On the back: “Fisherman [sic] 850, Cormorants 10.” The marinas also sold T-shirts. One design had a circle-slash over a cormorant with the words underneath in caps and bold: “Zero tolerance.” Another had a picture of a bass, a perch, and a walleye on one side and a cormorant on the other. It said underneath “You Choose,” with a rifle’s crosshairs through the first “o” in “Choose.” I bought one of everything.

In addition to the difficulty of counting birds in the wild (it is even harder to count fish), it is also a challenge to know what exactly cormorants are eating and how much. Biologists use three primary methods.

The most accurate way is to shoot cormorants and slice open their stomachs to see what is inside. Every fisherman in Henderson Harbor has a story about what has been found in a cormorant’s stomach. Ron Ditch knows of an account by a local conservation officer who found a 17.25-inch (43.8 cm) catfish in a cormorant’s belly.

A second method to determine what cormorants are eating is to collect their “regurgitants.” These are barely digested fist-size balls, mushed up with fish or whatever else they have been eating. A regurgitant, also know as a “bolus,” can be difficult to find, however. They usually can only be collected on colonies, around the nests, and at a certain time of year when the adults are feeding their chicks. Sometimes chicks and adults barf up these regurgitants when they are frightened, a strategy used by cormorants around the world to defend against attacks from gulls, eagles, frigatebirds, and skuas, who all want to eat the cormorants’ recently caught fish or the cormorant chicks themselves (a sort of “here, take my wallet” defense behavior). One biologist told me that on Little Galloo he once found a half-digested fourteen-inch (13.5 cm) bass coughed up beside a nest.28

Because finding regurgitants is so limited and shooting the birds isn’t always ethically acceptable or even practical, another method biologists often use to estimate cormorant diet is to collect “pellets.” These are nutsize, gray, gummy blobs that cormorants cough up about once a day.29 Cormorants hack up pellets throughout the year. Cormorant pellets are convenient in that, similar to those of owls, they remain intact for a few days and contain bones, eye lenses, scales, and other parts of fish or other organisms that the birds have eaten and cannot digest.

I’m not a biologist, but I’ve spent my share of time over the years searching for cormorant pellets on islands of New England. So one of the high points of my professional career was when I was helping to collect pellets on Little Galloo Island. One of the state biologists said to his colleague as he placed a few pellets that I had just found into baggies: “You know, these coastal guys are almost as good as you, Irene. And you’re the cormorant puke magnet.”

Analysis of these pellets focuses primarily on tiny otoliths, the white oval ear bones of fish. Each fish species has a signature shape to its otolith. In theory, each pellet then reveals the species of fish and the number eaten from about one day’s worth of feeding. Unfortunately, there are some factors that can diminish the accuracy of pellets. For example, it can be hard at times to figure out if a given otolith wasn’t already inside a larger fish when the cormorant ate it, or even how many meals or days are represented in a single pellet.30

Indisputably, based on all these methods conducted in various parts of North America for over a century, double-crested cormorants are opportunistic feeders, just as are most other cormorant species. Cormorants dive underwater after whatever fish is the easiest to catch at a given time. Biologists have identified as prey for double-crested cormorants across North America more than 250 species of fish from over sixty taxonomic families. These birds prefer slow-moving, schooling fish, most commonly less than six inches (15 cm) long. Cormorants also eat eels, and the occasional crustacean, amphibian, insect, or even small mammal. I read a report of a double-crested cormorant eating an entire snake.31 One study in North Dakota in the 1920s found that owing to environmental conditions, cormorants shifted their diet to eat primarily salamanders.32 On rare occasions, cormorant species around the world have been observed eating small rodents and other birds.33

All cormorants around the world eat live food. Cormorants do not eat dead fish, carrion, or human trash.

Biologists try to determine an average of how many fish, or the weight of fish, a cormorant will eat on a given day. This is challenging because birds have different needs based on time of year. They are going to eat the most, for example, when they are feeding chicks.

The two most cited experts on double-crested cormorant biology—Jeremy Hatch, an Englishman who spent much of his career at Boston University, and Chip Weseloh, a biologist for the Canadian Wildlife Service, reported that double-crested cormorants eat on average about 0.7 pounds (0.32 kg) of live food per day.34 A couple of years later Weseloh revised this average up to 1.0 pounds (0.47 kg) in a study conducted with the cormorants of eastern Lake Ontario.35 A healthy adult cormorant is bigger than a duck and smaller than a goose. It typically weighs about four to five pounds (1.8–2.3 kg).36 So according to these studies, a double-crested cormorant’s average daily consumption is about 20 to 25 percent of its mass.

So do cormorants have a bigger appetite than other birds?

Over a century ago in The Birds of Ontario (1886), Thomas McIlwraith wrote (which would hardly be the last word on the matter): “All the Cormorants have the reputation of being voracious feeders, and they certainly have a nimble way of catching and swallowing prey, yet it is not likely that they consume more than other birds of similar size.”37

Ron Ditch and his fellow fishermen are not the only men to go out and kill cormorants around the Great Lakes. In the 1930s ornithologist T. S. Roberts wrote that cormorants got into the pound nets and gill nets of commercial fishermen around Lake-of-the-Woods, Minnesota, which is beside the Canadian border. Roberts wrote: “Fishermen grant [cormorants] no quarter and destroy them whenever possible by shooting the adults and breaking up their nesting-places on islands in the lake.”38

More recently, a Canadian colleague told me: “I’ve heard some crazy stories of locals in Manitoba attacking colonies with weed-whackers, and men shooting at conservation officers who try to stop them.”39

In June of 2000 more than five hundred cormorants were shot on Little Charity Island in Saginaw Bay, part of the Michigan Islands National Wildlife Refuge. Some person or group gunned down half the breeding population—many of the birds were sitting on eggs and newly hatched young.40 Authorities never caught the offender(s).

Two years later, recreational fishermen from Cedarville, Michigan, made their own national news complaining about their cormorants. Tourism was down. Fishing resorts were closing. Local fisheries managers documented a near crash in the perch population. As cited in this chapter’s epigraph, Cedarville residents proposed cormorant culls, and—hopefully with hyperbole—advocated calling in the U.S. military to “napalm the rookeries.”41

In 2007 men shot birds and crushed eggs and nests at several cormorant colonies on Canadian islands in Georgian Bay, Lake Huron. Controversy about cormorants and pressure from sport fishermen for government action had been under way there for at least a few years.42

When two decades earlier, in 1987, some eighteen hundred cormorant eggs were illegally, clandestinely destroyed on an island in northern Lake Michigan, poet Judith Minty responded with verse. Minty wrote in her poem “Destroying the Cormorant Eggs”:

the cormorants now emitting faint squawks,

flapping their wings over this darkness,

the albumin and yolk, the embryos shining on dull rock,

the small pieces of sky fallen down—Black

as the night waters of a man’s dream where he gropes

below the surface, groaning with the old hungers.43

Double-crested cormorants are native to the North American continent. They are not “alien” or “invasive” or “exotic” by any wildlife management definition. There is, however, not as much evidence of cormorants nesting in the Great Lakes before the twentieth century, as compared to other records in other regions of the continent.44 Cormorant advocates argue, however, that there are several early records into the nineteenth century of abundant breeding in the Prairie provinces, Ontario, and the surrounding midwestern states. It also turns out that there isn’t that much archaeological or pre-twentieth-century anecdotal information for any of the now common seabirds of the Great Lakes.45

And a few records of cormorants in the bordering areas do exist. These accounts suggest nesting of cormorants across most of the Great Lakes.46 For example, in 1887 a naturalist near the Minnesota-Iowa border heard the locals declare (thinking the cormorants were loons): “The air is jist black with em’ [sic] an they’re nestin’ on the island so yer can’t see it for eggs.”47

Twenty years earlier, a man described cormorants living around a man-made reservoir in Ohio: “About seven miles from Celina, was the ‘Water Turkey’ Rookery. Here I used to go to shoot them, with the natives who wanted them for their feathers; I have helped kill a boat load. One season I climbed up to their nests and got a cap full of eggs. The nests were made of sticks and built in the forks of the branches. The trees (which were all dead) were mostly oaks, and covered with excrement. I found from two to four eggs or young to a nest. The young were queer little creatures—looked and felt like india rubber.”48

In addition to a handful of anecdotal accounts like these within a few hundred miles of the Great Lakes, we know of huge populations nesting in the Canadian Maritimes at the time of European contact, as well as a few early records of staggering numbers of cormorants transiting up and down the Mississippi.49 It is hard to imagine that these highly mobile animals did not, if the food was available, regularly nest and roost in Lake Ontario, perhaps even on Little Galloo Island, in the centuries before human disturbance.

The first ornithologist to do a comprehensive study of double-crested cormorants—or of any single cormorant species in the world, as far as I know—was Harrison Flint Lewis in 1929. While serving as chief migratory bird officer for Ontario and Québec, he worked toward his PhD at Cornell University. He did his field research on cormorants in the Gulf of St. Lawrence but compiled as much information as he could about the bird’s life history throughout North America. He corresponded by mail with colleagues all over the continent. He dug through libraries and archives. Lewis’s research was sound and foundational. Today doing work on cormorants in North America and not mentioning Harrison Flint Lewis is akin to working on chimpanzees and not mentioning Jane Goodall.

Lewis’s writing was tempered wonderfully with the tone of his time. It was in this way that he concluded his natural history: “In ending for the present this paper about the Double-crested Cormorant, I do so with the hope that it may show that that bird, though unfortunate in some respects, is by no means as unpleasant as it has often been painted, but is actually a reputable avian citizen, not without intelligence, amiability, and interest.”50

Though he sounds tepid there, Lewis was an active cormorant sympathizer. He looked into the possibility of harvesting cormorant guano for fertilizer in the Canadian Maritimes. He thought cormorants’ killing of trees was “local and limited.” Lewis’s research, following that of previous biologists, showed that the cormorants did not eat much if any of the Atlantic salmon or the trout of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, as some fishermen had accused the birds of doing.51

In 1929 Lewis calculated that in North America there lived fewer than forty thousand double-crested cormorant individuals of what we now refer to as the Interior and Atlantic populations, known collectively as the subspecies P. auritus auritus.52 Of that continent-wide total of cormorants, fewer than three thousand lived within the borders of the United States, mostly in colonies around inland lakes in Minnesota and South Dakota.53 Lewis wrote: “The history of the Double-crested Cormorant during the latter part of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth is largely a history of persecution and of the gradual abandonment of one breeding-place after another.”54

Since then, the graph of the numbers of breeding pairs of double-crested cormorants of the Interior population, mirroring the other populations around the continent in most respects, has been nothing but a roller coaster. By the 1940s, as Lewis was being promoted to chief of the Canadian Wildlife Service and Ruddy Ditch was taking his young son Ron fishing on Lake Ontario, the Interior population of cormorants had begun to increase quickly. This was probably due in part to the creation and protection of reservoirs in order to meet the water needs of an expanding human population in the Midwest and the Prairie provinces.55 Maybe persecution from people in New England and the Maritimes pushed the birds inland. In the 1940s and 1950s there were perhaps 200 to 240 cormorant nests on Lake Ontario.56 Wildlife biologists in Manitoba, meanwhile, felt so threatened by population growth in their area, particularly around Lake Winnipegosis—which had reached nearly 10,000 breeding pairs—that managers began officially shooting birds and destroying nests in 1943. In less than a decade they had halved the local population. The official program was discontinued.57

From the 1940s through the 1960s cormorant numbers began to decline again throughout North America, but not solely because of culling programs. Farmers had begun to widely use pesticides such as DDT. These and other industrial contaminants long in use, such as PCBS and DDE, had continually seeped into lakes, rivers, and coastal waters throughout the continent.58 The chemicals got into the systems of birds through the fish they ate, thinning the cormorants’ eggshells.59 In Green Bay around this time, for example, more than one in every two hundred cormorants was born with a defect, such as a curled, deformed beak.60

By 1970 there were again fewer than one hundred pairs of cormorants throughout the Great Lakes. There was only one colony on Lake Ontario. It had two nests.61 In 1972, Wisconsin listed the double-crested cormorant as endangered and erected nesting structures to help them recover. The National Audubon Society listed the cormorant of “special concern.” The Prairie provinces also experienced huge drops. Officials in Alberta designated the cormorant as endangered.62

Then cormorants throughout North America, especially those of the Interior population, began to rebound once again. Environmentalists such as Rachel Carson inspired and nudged the introduction of several green laws in the 1970s. Legislators passed the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act. They banned chemicals such as DDT. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 was revised in 1972 to include additional birds, such as the cormorants.

Coincident with these pieces of legislation and the official protection for cormorants and their habitat was the rise of the aquaculture industry in the South. Catfish farmers in the Mississippi Delta constructed thousands of open ponds, all stocked tightly with fish. This supplied migrating cormorants and other fish-eating birds with a convenient and easy food supply in the wintertime.

As the cormorant numbers began to climb once again and the birds became more and more visible, men such as Ron Ditch complained louder and louder about the loss of their fish. Fish farmers, especially in the birds’ wintering areas, objected more and more bitterly that their hands were tied as to how to defend their crop against this blatant hit. Pockets of residents and conservation groups around the Great Lakes, inland freshwater bodies, and throughout the Mississippi Flyway began to clamor about the smelly colonies, the killing of the trees, and that cormorants were pushing out other, more-valued birds.

Double-crested cormorants migrate. The birds of Little Galloo might spend the winter months anywhere from Mexico to North Carolina. Thus a federal agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), is in charge of the big picture of cormorant management. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act is not just for birds flying within the United States, but it also represents in part an agreement among Canada, Mexico, and Japan. For cormorants, the treaty is primarily between the United States and Mexico, since Canada’s cormorants are protected by provincial legislation, not federal. The USFWS is mandated to enforce the treaties that protect wild birds—yet right beside the agency’s conflicting responsibility to promote aquaculture.63

So the USFWS had to respond to this public outcry against the growing cormorant population. In the mid-1980s it began issuing a few control permits in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services division. In 1998 the USFWS granted permission for catfish farmers in several states to shoot cormorants on their ponds. It was that summer when Ron Ditch and his fellow fishermen raided Little Galloo Island. The following spring the USFWS allowed wildlife biologists onto Little Galloo Island to start oiling eggs at the start of the breeding season. To oil eggs, a few technicians or biologists enter a rookery and coat all the eggs in the nests with a sprayer connected to a backpack full of vegetable oil. The chick fetuses suffocate without the ability to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide through the shell, but the parents are unaware. The adults keep brooding for several more weeks. If the wildlife biologists just went in and destroyed the eggs, the cormorants would likely try to lay a second clutch.

Still, the shooting on the aquaculture ponds and a few local egg oiling and harassment programs in several states under various permits were not doing enough, fast enough.64 Demands for action continued, especially around the Great Lakes. Ron Ditch’s big shoot in 1998 spurred several editorials and official position statements.

The USFWS began a grueling, multiyear analysis and public comment period. Several groups pushed for more oiling of eggs, direct culling, and more states’ rights in determining how to manage their local populations without needing federal permits. Some cried out for a hunting season for cormorants. Other interests, including the National Audubon Society, the Humane Society of the United States, and later one environmentalist group called Cormorant Defenders International challenged both the science and the management goals.

In 2003 the USFWS settled on a comprehensive double-crested cormorant management plan. They expanded the rights of citizens and managers to deal with cormorants, handing over much of the decision making to selected local agencies within broad parameters. So, in thirteen states today fish farmers may shoot cormorants on their private ponds. They may call on government wildlife biologists to shoot birds on nearby roosts. These provisions are termed the “aquaculture depredation order.” In twenty-four states, including New York, local managers may oil eggs, destroy nests, or kill cormorants that threaten what are considered public resources, such as wild fish, wild flora, and other birds’ rookery space. This is termed the “public resource depredation order.”65

From 2003 to 2006, Canadian wildlife biologists heavily managed growing cormorant populations on two islands of Presqu’ile Provincial Park, on the northern shore of Lake Ontario. They did so in order to protect native trees and leave more space for egrets, night herons, and migrating monarch butterflies. It seems logical that thousands of these cormorants were previously on Little Galloo or other sites on the other side of the border. Managers at the park reduced the breeding cormorant population by egg oiling, nest destruction, and the killing of thousands of adults—including shooting over six thousand individual birds in 2004. In a few years they reduced the number of breeding pairs from 12,082 to 2,819.66 Managers shoveled the carcasses with ATVS equipped with front-end loaders and dumped the birds in composting bins on one of the islands.67

Each year of the cull, environmental groups filed complaints. Canadian citizens took to small boats, Greenpeace style, in order to film and record as much of the culling as they could. They rescued injured birds found floating in the water.68

Canada does not as yet have a countrywide management plan or a federal branch that deals with agricultural animal management. But their cormorant conflicts are many, similar, and in almost every province.69 Chip Weseloh, who agrees with selected cormorant management in certain places in order to preserve space for other nesting birds or maintain rare vegetation, explained to me that despite a few culling programs, like that at Presqu’ile on Lake Ontario or on Middle Island in Lake Erie, “in Canada, we do very little of that.”

At the same time, Weseloh tells me: “In Ontario land owners can do virtually anything to protect their property values from harmful wildlife without a permit and without having to report their actions. We usually do not know how much land owner control or management or culling there might be.”70

Russ McCullough, senior aquatic biologist, has been with New York’s Department of Conservation for over thirty years. He loves his job. It places him firmly in the middle of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, environmentalist groups, and the needs of his local community, including the recreational fishing interests and the tourism industry.

When I first met McCullough, a couple of years after Ron Ditch’s cormorant shoot, he said: “To me cormorants are an issue like zebra mussels are an issue or like phosphorous levels are an issue. If there is a problem, then you’ve got to deal with it. But I don’t really have the emotional connection to the birds like some people do.”71

McCullough was one of the people who first discovered the dead birds on Little Galloo. He and his colleagues were going out for a routine trip to collect pellets, which was by chance only two days after Ditch and the others went ashore with their guns. As usual, McCullough and the others anchored off the island. They began to row ashore in an inflatable. They were familiar with the powerful smell of the guano, but this time the place smelled much worse. Something was rancid. Russ and a couple of other state biologists began to walk around the perimeter of the island as they normally did. It is common on a bird rookery to find a few dead chicks. They die naturally. They starve, outcompeted by stronger siblings. Gulls eat them. “But this was different,” McCullough says. “There were just too many. We saw some shotgun shells, saw the groups of cormorant chicks all dead together. Some birds were wounded, still alive. Two of my colleagues had to euthanize them with a hammer.”

McCullough thinks the killing of the cormorants on Little Galloo Island was a grossly illegal activity. It was not civil disobedience, he says, because Ron Ditch and the other fishermen denied it at first. At the time of the shooting, his agency was in the middle of assembling a huge report on the matter. They were thoroughly aware of the problem and were in the process of identifying strategies. McCullough wants to think that it was their final report that finally got management approval from the USFWS to begin to oil eggs. But he knows that the shooting raised awareness, particularly with the politicians. McCullough quickly points out that the incident also slowed down Ron Ditch’s cause, because certain agencies and private groups now did not want to allow any management at all, since that would only reward this type of activity. With the national press and environmental groups now watching closely what was happening on the island, cormorant management was stifled.

He does not demonize Ron Ditch, however. For McCullough, it is important to recognize that the ideas of scientists are just as value driven as anyone else’s. Even the notion of biodiversity is a value, not a fact.

“We biologists need to recognize that we have values, too,” McCullough says. “When we make decisions, and we develop ideas, it has got the values attached to them. So let’s recognize that and not say ‘Well, ours is the truth, ours is fact driven and theirs is value driven.’ It doesn’t work that way. This cormorant issue, it was such a hot issue. And it still is pretty hot. But it’s brought a lot of stuff out in the open. That’s been positive.”

Value judgments are certainly at the root of whether or not to kill cormorants in order to preserve certain flora or fauna on islands. Some conservationists are in favor of cormorant management on Little Galloo in order to assist the nesting of the few remaining black-crowned night herons and other colonial waterbirds, such as Caspian terns.

What is happening underneath the surface—how much cormorants are actually to blame for diminishing fish stocks—is a far more complex matter, especially in the Great Lakes. McCullough explains to me some of the variety of factors that have affected the fishery in eastern Lake Ontario over his thirty years.

But before he begins teaching me about the ecology of the region, McCullough says, “Firstly, there is nothing natural about Lake Ontario.”

What McCullough means by this is that the Great Lakes have been vastly manipulated by industrialization, fishing pressure, introduced species, and stocking programs. The first records of accidentally introduced sea lampreys and alewives in the lakes are in the late nineteenth century.72 Rainbow smelt appeared in the 1930s. Then, coincident with the later twentieth-century rise in cormorant populations, Canadian and American managers in the late 1960s and early 1970s intentionally introduced Pacific species of salmon, such as coho and chinook, and different species of trout. They hoped to counteract the rise of the alewives, which, combined with the sea lampreys, it was believed, had helped decimate the native lake trout and perhaps the native Atlantic salmon. Alewife populations did especially well in the 1970s through the 1990s. It also turns out that the alewife, a small schooling fish, is an ideal food for cormorants. Then in the 1990s zebra and quagga mussels spread throughout the Great Lakes. These invasions, along with other primary productivity shifts, made the water in eastern Lake Ontario clearer, surely shifting the movements of fish, such as smallmouth bass.73 Finally, by the time Ron Ditch and his gang hit Little Galloo Island in the late 1990s, a fish called the round goby had arrived accidentally in Lake Ontario from Eastern Europe and would quickly become a dominant species.

All that is just to say that in the Great Lakes, there are a lot of fish under there eating each other, and people have been continually manipulating the ecology of this region—intentionally and accidentally—with extraordinary intensity over the last century. Yes, Russ McCullough thinks cormorants affected the local fishery—they eat a lot of fish—but he does not think the birds are one of the most significant of factors causing the depletion of bass or any other given species.

These days Ron and Ora Ditch spend their winters at a condominium in Florida. Off the beach or out on the water, Ron regularly sees double-crested cormorants down there, both those of the Southern population that live in Florida all year round, as well as those from the Interior or Atlantic populations who have also migrated down for the winter. Quite possibly Ditch has seen individuals that spent that year nesting on Little Galloo Island.74 Directly in front of the Ditches’ condo, to their distaste, they regularly see an anhinga—the cormorant’s closest relative and a black waterbird that looks quite similar.

Ron Ditch applauds the state’s egg oiling and the culling of cormorants. Since the 1999 egg-oiling permit and the state’s killing birds on Little Galloo as a result of the 2003 federal plan, wildlife biologists have met their goal of bringing the population down to the predatory impact associated with 1,500 breeding pairs on the island. At least for now, the NYSDEC staff continues to manage the colony in order to maintain this level of predation on fish—to make sure the cormorant population does not just bounce right back up.75

“Our intention was never to destroy the birds completely or get rid of them completely or put them on the endangered species list,” Ditch says. “Our intent was to get them down to a number that we could live with and that would allow the fishery to rejuvenate. That is where we are right now. The fishery is coming back to the levels of where it was before the cormorants—I call that ‘BC.’ Before Cormorants. So that’s proof in the pudding.”76

McCullough and his colleagues, including Irene Mazzocchi, who now oversees the cormorant management on Little Galloo, and Jim Farquhar, who previously held the post (and now has a cormorant printed on his regional wildlife manager business card), all seem generally satisfied with the management’s progression, too.

McCullough was a coauthor on a study recently that showed that 92 percent of the cormorant diet from Little Galloo Island is now the introduced round goby. Smallmouth bass composes 0.1 percent.77 Yet the state wildlife biologists are planning to stick with their present level of egg oiling and culling, for at least a few more years.78

Each April when Ron and his wife return from Florida to their home in Henderson Harbor and Ruddy’s Fishing Camp, they put up bird feeders and several birdhouses. Their home is decorated with paintings of ducks. Beside their dining room table is a large painting of a few scarlet ibis. Ron has always been a hunter. In the early years, he made money during the off-season carving duck decoys out of wood. When plastic decoys took over, he crafted and sold more-decorative bird carvings. These are all over his living room. Some are really quite exquisite, especially his small birds in flight, which have delicately carved feathers and paper-thin webbed feet.

Recently, while I was visiting with Ron Ditch again, he told me that he got it into his head that he wanted to carve a cormorant. Perhaps he would use it in his talks. So he spent several months, much of his downtime in Florida, whittling away at a life-size double-crested cormorant. When home at Henderson Harbor, he worked off a mounted bird that a taxidermist in town had prepared. The wings of Ditch’s sculpture are out-stretched—every single feather is carved: every rachis and every barb. He painted the bird a sharp black. Its mouth is open. It stands with its wide feet on a piece of driftwood. He made the double crests out of rabbit fur.

Ron Ditch doesn’t know what to do with his cormorant carving now. Or even where to put it.

“Maybe I’ll put it up on eBay,” he says.

“Look at that lousy bird,” says Ora. “Bird from hell.”