CHAPTER 2

Reading

Reading comprehension is the ability to understand a reading passage. On the A2 test, you will be given a reading passage with some connection to health and medicine. It might be biographical, or it might resemble a general-interest magazine article. Rarely will you see a passage on the A2 that is overly technical or that requires specific training. All of the questions derive directly from the passage, not from any background knowledge you are expected to have in the area being discussed.

MAIN IDEA

The main idea of a passage is a statement that tells what the passage is mostly about. When you look at the front page of a newspaper, you get a sense of the main idea of the articles by scanning the headlines.

Main idea differs from topic in that it is more complex. For example, the topic of two different articles might be “vitamin supplements.” However, the main ideas could differ significantly. The main idea of the first article could be “Scientists find that taking vitamin supplements is less effective than eating well-rounded meals,” while the main idea of the second could be “Vitamin supplements cost more at health stores than at pharmacies.”

To determine the main idea of a passage, ask yourself these questions:

• What information do I learn in the introduction and conclusion of this passage?

• What is the author trying to get me to believe or understand?

• What statement would gather together all of the details in the passage?

Stated Main Idea

Sometimes an author makes it easy for you by expressing the main idea directly in a statement. Usually that statement will appear in the opening paragraph of the passage. This passage has a statement that expresses the main idea directly.

Implied Main Idea

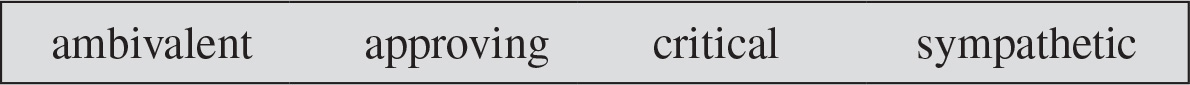

Often, there is no direct statement that tells you the main idea of the passage. You need to infer the main idea from the details in the text. Consider the focus of each paragraph and decide how the details fit together to form a common viewpoint, argument, or theory. Imagine you read a passage whose topic is yoga for the elderly. (See Figure 2.1.)

Figure 2.1 Inferring Main Idea

SUPPORTING DETAILS

Supporting details in a reading passage are all of the facts, descriptions, and examples that make up the body of a passage and support the main idea.

5 W’s

It is sometimes helpful to think like a journalist as you approach a complex passage. Think about the answers to what journalists call the 5 W’s:

• Who (or what) is this about?

• What happened?

• When did it happen?

• Where did it happen?

• Why did it happen?

The answers are all supporting details.

Evidence

In a piece of writing that states an opinion or presents an argument, supporting details constitute evidence in support of the opinion or argument.

Suppose that an author claims the following:

Homemade baby food is preferable to store-bought.

In support of that claim, the author might offer a variety of facts, descriptions, and examples.

• Evidence 1: Baby food fruit in jars contains five grams more sugar than kitchen-mashed fruit.

• Evidence 2: Store-bought food may look shiny and appetizing, but that may be due to added food coloring.

• Evidence 3: The fillers in one brand included starches that babies could not easily digest.

All of these details add up to a condemnation of store-bought baby food and strong support of the author’s claim.

WORDS IN CONTEXT

Technical writing and complex texts often include vocabulary that may be unfamiliar. You must infer the meaning of such words by using context clues—semantic and syntactic clues that appear in the text surrounding the unknown word.

If you saw a nonsense word out of context, it would simply be nonsense:

brufle

But if you read it in context, you could draw some conclusions about its meaning:

When confronted, Jack tends to brufle and look away.

Its use in this sentence (its syntax) suggests that brufle is a verb. It apparently describes an action that a person might do when confronted by someone else.

See? Even if the word is completely foreign to you, you can determine a lot about it from its context in a sentence and by the meaning of the words around it (semantics).

There are various semantic and syntactic clues that make determining the meanings of words in context easier. Here are just a few.

Definition/explanation

Sometimes the word in question is defined directly by a phrase that clarifies its meaning.

• The tonic was salubrious, offering a variety of healthful benefits.

• Five of the nurses gathered in amity, an aura of goodwill and friendship.

Restatement/synonym

A word that means the same thing may make the meaning of an unfamiliar word clear.

• Her experiment was an unalloyed, total disaster.

• His office was a maelstrom, with a whirlwind of papers flying around.

Contrast/antonym

A word that means the opposite of the unknown word may help to illuminate its meaning. Words such as unlike and whereas may signal this contrast.

• Whereas the doctor was magnanimous, his wife was stingy.

• I prefer honesty and truthfulness to deceit and artifice.

Inference

As with the nonsense word brufle above, sometimes you must simply use syntactic and semantic clues as well as your own prior knowledge about the English language and the topic being discussed to decipher an unknown word.

• His statement seemed specious, so we chose to ignore it.

• It takes a certain mettle to survive such a difficult childhood.

AUTHOR’S PURPOSE

Writing is two-way communication between an author and a reader. Authors write with a purpose in mind. Understanding that purpose can help you to interpret their writing more easily.

Persuasion

Authors who write to persuade want something from their readers. They may want the readers to change their minds about a contentious topic. They may want the readers to take action.

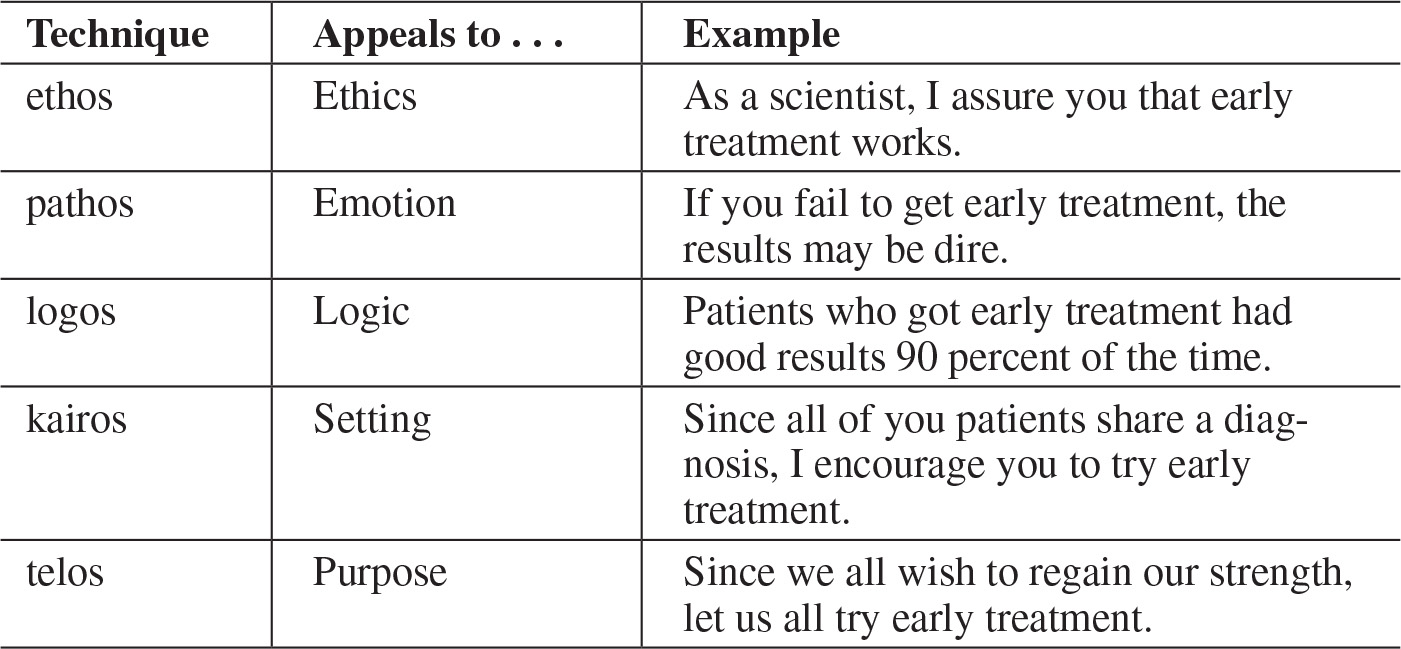

Persuasive writing expresses an opinion, states a claim, and/or presents an argument. Typically, persuasive writers use one or more of these modes of rhetoric, shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Rhetorical Techniques from the Ancient Greeks

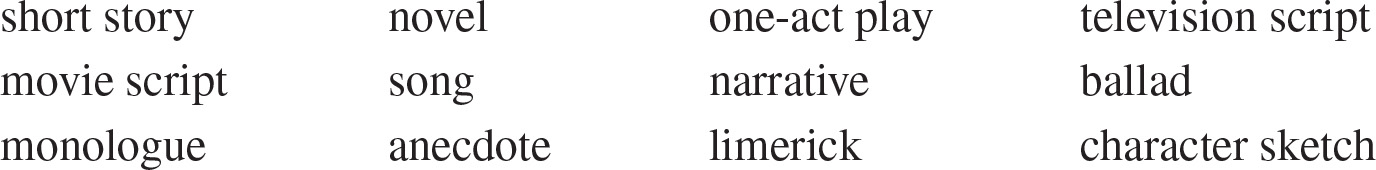

If a passage expresses the author’s concerns, beliefs, or opinions, its purpose is probably persuasive. Look for persuasive words and phrases like those below.

• Without a doubt

• I am convinced

• I believe

• You should know

• You can see

• Clearly

• Obviously

• Unmistakably

Information

Most of what you read and write in college and in nursing school is likely to be informational, or expository writing. Informational writing relies on facts. Its purpose is to explain a process or an event, to describe something in detail, or to inform the reader.

Informational writing is impersonal and largely unbiased. It may compare and contrast two things but will not choose sides. It may tell the reader how to do something but will not tell the reader that he or she should do that thing.

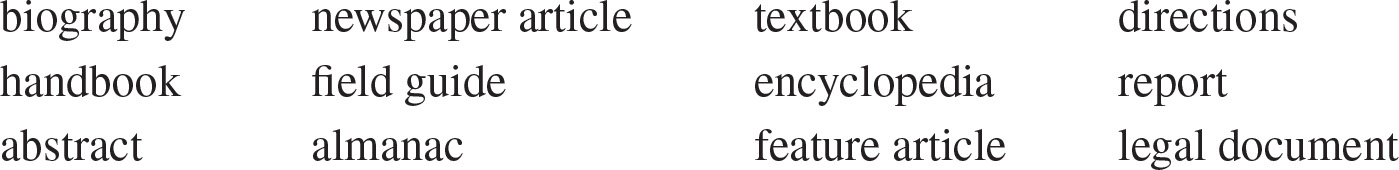

Examples of Informational Writing

If a passage is filled with names, dates, statistics, and quotes, it is probably informational.

Entertainment

Authors of fiction, drama, or poetry write primarily to entertain. Entertaining writing may engage the reader using suspense, humor, tragedy, or fascinating characters and settings. When we talk about “creative writing,” we are usually talking about writing whose purpose is to entertain.

Examples of Entertaining Writing

Reflection

Sometimes, authors write to reflect upon personal experiences or to share personal responses. This sort of personal writing differs from persuasion in that the author is not trying to convince the reader of anything. The author may be writing to explore his or her own thoughts or to gain self-knowledge while involving the reader in that personal journey. Reflective writing turns up in certain memoirs, essays, poetry, and solo performances.

FACT AND OPINION

Determining whether a statement is fact or opinion is not the same as determining whether it is accurate or untrue. Most of what you read as a medical professional will involve multiple facts. Recognizing when the author’s bias pushes into the writing with ideas that may not be verifiable is a useful skill to have.

Facts

A statement of fact is objective and can be checked or proved. It may be true or false, but it is always provable one way or the other.

• The patient is currently in room 305A.

• The patient’s name is Lucia Alvarez.

• The patient’s fever reached 102 degrees.

Opinions

A statement of opinion is subjective and cannot be checked or proved. It may represent one person’s judgment or the beliefs of thousands, but it is not verifiable through any scientific means.

• The patient’s diet was appalling.

• The patient should not be moved yet.

• The patient deserves our attention.

A Few Words That Signal Opinions

Sentences that contain vivid adjectives and adverbs usually indicate judgment and are probably opinions rather than facts.

• The patient has an unpleasant odor.

• The patient’s skin feels leathery.

• The patient treats the nurses rudely.

DRAWING CONCLUSIONS AND MAKING INFERENCES

As you read, whether you are aware of it or not, you apply what you know and clues from the text to draw conclusions or make inferences about what you are reading. For example, if you receive political mail around election time, you can probably easily tell which party sent it without even looking for a party insignia. Your knowledge of local political parties and their interests and focuses added to the information in the text allows you to infer the identity of the sender.

Drawing conclusions and making inferences are part of being an active reader. Instead of expecting an author to deliver everything you need to know in a text and to explain how you should think or react, you must determine for yourself how facts and details fit together; what information is not provided but can be guessed at or surmised; and how the information given supports additional conjectures, predictions, or judgments.

Using What You Know

When you draw conclusions or make inferences, you apply your own background knowledge to a text to make assumptions. An author, therefore, must be fairly aware of his or her audience in order to get readers to draw the desired conclusions.

Imagine this sentence in a text:

The old man’s chest rose almost imperceptibly, and his bony fingers grasped at nothing.

A child reading this might not be able to conclude what an adult would—that the man’s health is failing, and he may be near death. Only life experience and a lifetime of reading would let a reader draw that conclusion.

Here is another example:

The yacht’s wake was the only blemish on the turquoise Aegean, and the caw of whirling gulls the only sound to disturb our languor.

The author does not bother to remind you that yachts are not an ordinary form of transportation or to tell you where the Aegean might be. If you know about yachts, the Aegean, and languor, you can conclude that the people being described are wealthy.

The more you live and the more you read, the better you will be at making inferences and drawing conclusions from a text.

Using Textual Clues

An author does not tell a reader everything, but he or she does tell the reader some things. Using the clues that are given in the text can help you to draw conclusions and make inferences.

Consider this example:

The antipersonnel mines indiscriminately kill civilians or soldiers, young children or old women.

The word mines has a variety of meanings, but you can determine from the surrounding text which meaning is implied. Coal mines might be harmful to some workers, but they would not kill soldiers, children, or old women. This sentence refers to land mines, explosive devices designed to kill.

Here is another example:

Following the opening of the high-end organic grocery down the block, the bodega appeared to lose first its bustling exterior, then its scrubbed storefront, and finally most of the contents of its shelves.

The author does not directly tell you what happened to the bodega, but the loss of bustling, scrubbed, and, finally, contents implies a slow decline in its success. The fact that this is linked to the “opening of the high-end organic grocery” tells you that the author wants you to infer that the cause of the decline is the appearance of the new grocery.

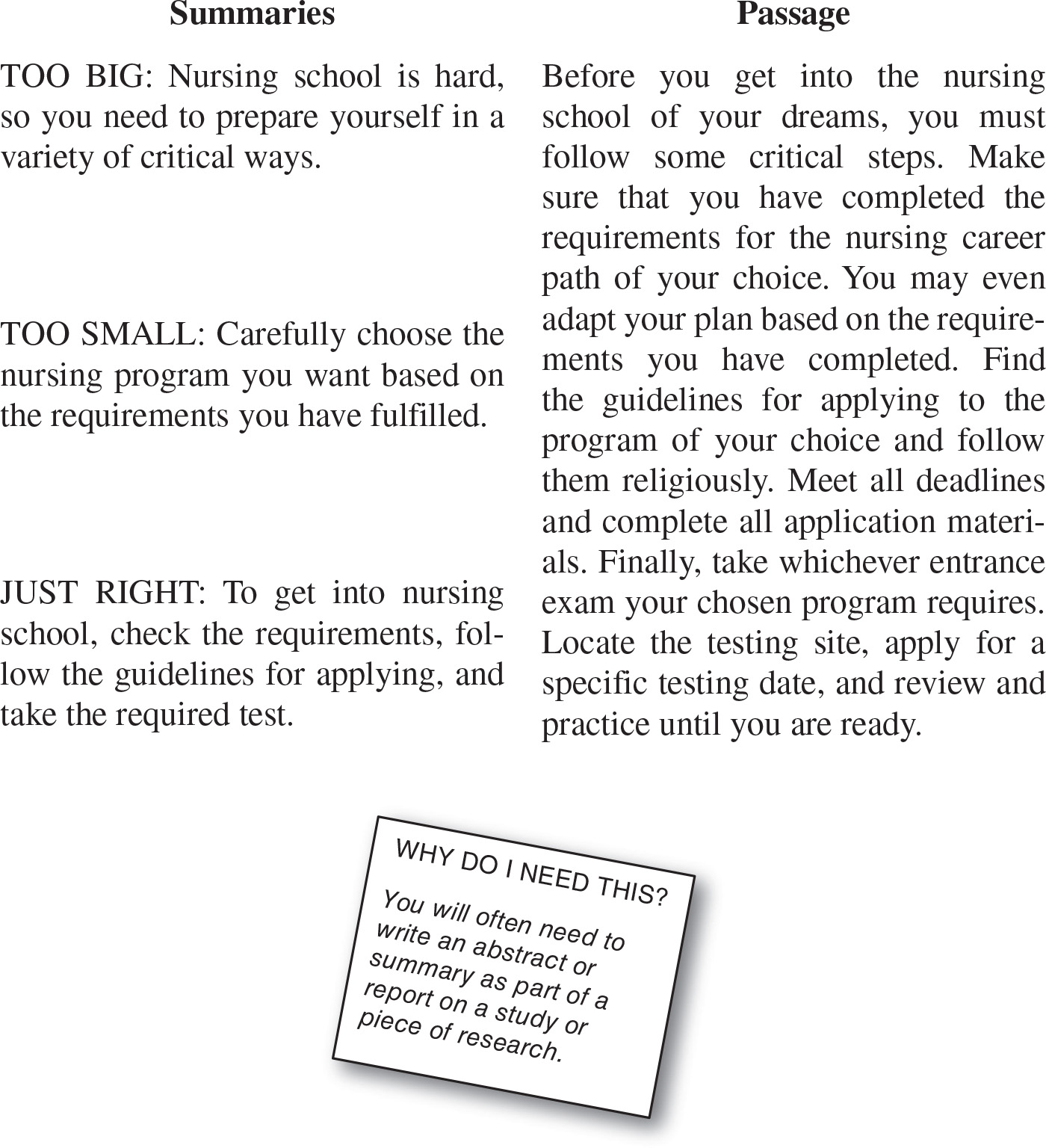

SUMMARIZING

When you summarize a paragraph or longer passage, you restate the main idea and key details expressed in the writing. A summary answers the question, “What is this mostly about?”

Good summaries follow the Goldilocks precept that applies to the three bears’ chairs. A good summary is not too big—it does not cover material or ideas that do not appear in the original writing. A good summary is not too small—it does not focus narrowly on a single point in the original writing. A good summary is “just right”—it is a brief restatement of the key points in the original writing.

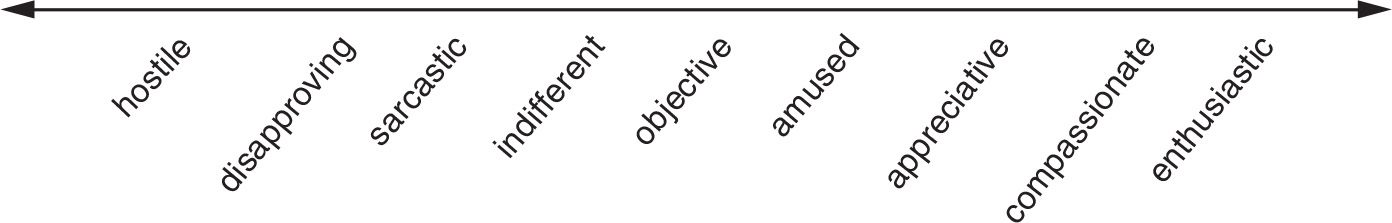

AUTHOR’S TONE

An author’s tone indicates the author’s attitude toward the subject matter. That attitude determines the words the author chooses, and those words in turn indicate the author’s point of view.

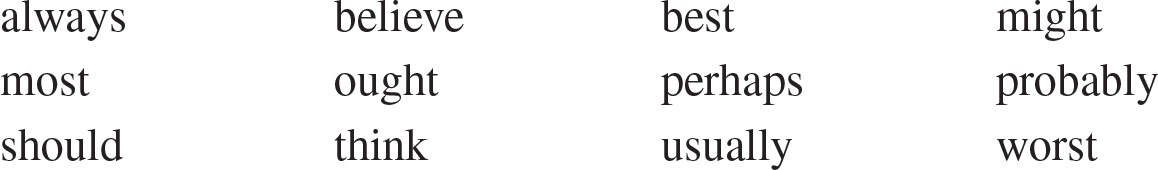

Figure 2.2 shows just a few examples of words that may be used to describe an author’s tone.

Figure 2.2 Tone Scale from Negative to Positive