Katta had not been able to make Mathias understand just what it was they had to do. She hadn’t dared speak above a whisper, and though she kept tugging at his coat, she couldn’t get him to move. He slumped in the dark, his breath coming in short, painful gasps. It was pitch dark all about them. So dark that he couldn’t see what she already knew – that they were at the opening of a low tunnel, not quite high enough for a man to stand fully upright in. It ran beneath the barn and curved away into the forest. At its other end there was a track. Not a track that was meant to be noticed, but it was there all right. A lot of people came and went from that inn. A lot of things too, not all of them meant to be seen – small barrels and rolls of fine cloth – things that had never seen an excise man or paid the tax due. Things that took the back roads and were gone the next day. That’s what the tunnel was for. That was what the inn was really about, and anyone who interfered or asked too many questions just wasn’t seen again.

Katta had found the tunnel quite by accident one wet day, climbing amongst the barrels in the old barn. She had even been down it, just once. It had scared her so. The roots of the trees trailing through the earth roof, the smell of the damp, the small showers of soil falling on her as she passed beneath. She’d been terrified that at any moment the roof might come down on her in one suffocating collapse, burying her deeper than any grave. She’d gone just as far as she could dimly see, then her nerve had given out and she’d scrambled back to the opening, her heart pounding and her skin wet with fear.

But it was the first thing that came to her when she’d seen Mathias trying to reach the trees – that she could hide him in the tunnel. It was only as she closed the hatch above their heads and felt the suddenly irresistible weight of the barrel drop back down with that ominous thump that she realized she couldn’t open it again. She hadn’t needed to close it the time before – she’d found it open and left it that way. Perhaps Mathias could have helped her push it, but he was barely able to stand. She could feel the cold damp air against her face and instantly knew what they would have to do. That air had to be coming from somewhere. With the hatch shut there was nothing for it but to go down into the dark until they came to the other end of the tunnel and hope that there was a way out. It was as this was running through her mind and she was trying in whispered words to make Mathias understand that she heard the sound of the barrels, one by one, being slowly and purposefully cleared from the floor above them. There was no time left. She grabbed Mathias by his coat and, not caring about the noise he made, shook him until she got him to stand up; then, taking hold of his arm, she pulled him after her into the dark.

Valter did not make a noise as he dropped through the hatchway into the dark space beneath it. Leiter stooped above him but made no effort to climb down. He had found a lamp and lit it.

‘It will be something small enough for him to have hidden,’ he said. ‘Find it, do you understand? Pull each one of his teeth from his head if you have to, but find it and bring it back to me.’

He handed Valter the lamp. Valter took it, grinned and, like a cat, was gone.

The tunnel curved and wound. About halfway along it had been dug wider to make a place in which things could be stacked. Katta, with one hand outstretched, the other dragging Mathias behind her, had groped her way along the wall until, not knowing it, she had come to that place. She couldn’t see a thing in the blackness, but there was a different smell in the damp air – sweet, of tarred wood and apples. It was as she stopped and tried to understand, to catch her breath and listen, that she realized that where a moment before it had seemed quite dark, now she could see the palest glimmer of light. It was just enough to make out dim shapes. For an instant she felt a wave of relief. She thought that they must have arrived close enough to the other end of the tunnel for the daylight to reach in. But then she went quite cold inside. The edge of the light was moving along the wall. It wasn’t daylight at all. There was someone with a lamp coming down the tunnel behind them.

*

Valter didn’t have to rush. This was the kind of game he liked best. The kind where people thought they could hide from him. Sometimes he liked to let them think that he couldn’t find them. He’d pretend just long enough so they believed that they were really safe. Then he could watch their faces as all hope vanished, and they understood not just that there was nowhere they could hide from him, but that he had known where they were all the time.

That was when Valter’s fun really began.

There was something else too. Something that Valter knew which Leiter didn’t. As he dropped down through the floor, he had breathed in. Yes. He was right. The boy was here – he could smell him. But he could smell something else too, and for a moment he was puzzled. He could smell almond paste and cooking, sweeping and hard work. It was a smell he could not place at once but vaguely recognized. Then it came to him. It was the smell of the serving girl. The one who had listened at the door. For an instant he hesitated. Should he tell Leiter? But Leiter didn’t need to know and it would make for so much more fun, there being two of them to play with.

He held the lamp out in front of him, drew a long, sharp knife from beneath his coat and began to walk slowly down the tunnel.

Katta looked desperately about her. Mathias didn’t understand what was happening at all. He had lumbered along behind her in the dark; now he stood still, swaying on his feet as though he might drop at any moment. She could run, but he couldn’t. The light was growing stronger. She could clearly see what the shapes around her were now: barrels and boxes. Lengths of wrapped oilcloth, all tied and strapped ready for the pack ponies. It was all piled up against the walls. She had to decide – there was no more time: the lamp would come round the bend in the tunnel at any moment and they’d be seen. They had to run or hide.

There really was no choice.

They had to hide.

Valter came round the bend. In the lamplight he could see the stacked boxes, the barrels and the oilcloth, and he knew at once that was where they were. He stopped. He couldn’t see them, but he didn’t have to. He could breathe them in amongst the brandy and barrels, the smell of boy and the smell of girl, close by. He cocked his head a little to one side and listened. He could even hear the quick sound of their hearts beating. No. No one had ever managed to hide from Valter.

Through the narrowest crack between a pile of barrels, Katta watched the dwarf. He stood with his back to her, holding the lamp up as he searched amongst the boxes on the other side of the tunnel. She ducked down just before he turned and the light swept past the place where they hid. She heard him moving things about and held her breath. But he didn’t find them. He walked on. She could hear the soft sound his coachman’s boots made on the earth floor as he went by. The light of the lamp grew fainter and fainter as he moved away. Then it was dark again. She let her breath go in a long, quiet whisper of relief. But now he was between them and their way out. Maybe, she thought, he would reach the end and come back above ground through the wood. Either way they were safe for the moment. They would just have to wait a bit longer. She settled back, and it was at this moment that Valter’s hand came slowly out of the dark and gripped her hair.

She screamed.

The dwarf had crept silently back in the darkness, the lamp and knife wrapped beneath his thick coat. Now he had Katta by her long hair, he drew the lamp out again so that he could look at her face as he pulled her from between the barrels. The boy was on the ground behind her. He hadn’t moved even when she screamed, but he was looking up at Valter with wide-eyed terror.

This was going to be a good game.

Valter flung Katta away – it was the boy he wanted first; he could play with her later. She crashed hard into the heavy boxes, all the breath knocked from her. The boxes swayed and fell on her. Pulling the knife from his coat, the dwarf reached down and, in one quick movement, passed it straight through Mathias’s shoulder.

‘Where is it?’ he said.

He pushed the knife through again. There was nowhere for Mathias to go. The dwarf dragged him out over the top of the barrels, threw him roughly to the ground, then sat astride him with the knife sideways between his teeth and his thumbs pressed hard into Mathias’s eyes.

‘Where is it?’

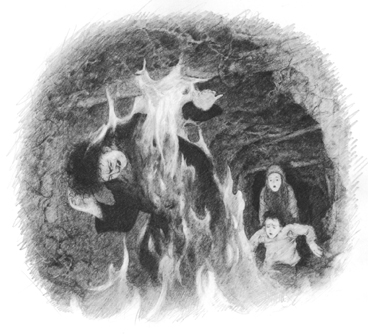

Katta’s head was ringing. She could see the dwarf on Mathias. She looked about for something she could use to hit him with. There was only the oil lamp. The dwarf had put it down on the ground beside him. She got unsteadily to her feet, picked it up and swung it as hard as she could. It hit Valter on the back of the head with a dull crack. The glass shattered, and instantly he was on fire. The oil from the lamp was thick in his hair; it soaked into his coat. He leaped up wildly, beating at the flames with his hands, but he was like a burning torch. The more he beat at them, the more the flames caught hold, until he was all fire. Screaming, he blundered blindly into the walls. The wooden struts that held the roof cracked and gave way where he hit them. Soil began to spill from above, first in small amounts, then in bucketfuls. Katta could see what was going to happen. The roof was going to give way. She caught hold of Mathias and began to drag him away. The flames from the burning dwarf lit up the whole tunnel.

Valter was still screaming as the roof fell.